|

LECTURE 1

Dornach, April 12, 1921

In these

afternoon hours I wish to present the first seeds of a curative eurythmy.

Today we will have a sort of introduction, and what we gain from it

we will develop into definite forms in the days following. First of

all I want to draw attention to some basic matters. What has been practised

up until now is eurythmy as art; and as such it should be concomitantly

accepted as the eurythmy pedagogically and didactically suited for

children, since what has been developed until now as eurythmy is in every

way drawn out of the formation of the healthy human being. We will see that

certain points of contact appear, by means of which it will be possible

to distil a hygienic-therapeutic discipline from the eurythmic, and

how certain artistic forms transform themselves in one direction or

another to become what can be called a sort of curative eurythmy.

It will, of

course, be essential to emphasize that artistic eurythmy — which

is in essence the expression of that element inherent in the formation

and in the tendencies to movement of the human body — is that which

must be adjudged correct for the development of the human organism as

soul, spirit and body, even as it is appropriate for visual presentation.

However, one can also work towards a curative eurythmy which will be

of extensive use in the treatment of various chronic and acute conditions,

but which will prove to be especially important and to the point in

those cases specifically where we attempt to treat impending sicknesses

and tendencies to sickness, prophylactically through eurythmy. Here

is the point at which the didactic-pedagogical element in eurythmy flows

gradually over into the hygienic-therapeutic.

However,

for those who wish to practise artistic eurythmy, I want to specifically

emphasize that they will have to forget in the most thorough fashion

what they have acquired in these hours when they do artistic eurythmy.

Then precisely in this area one must maintain a strict separation between

those goals which one pursues in hygiene and therapeutics and that artistic

quality which one must strive to attain in eurythmy. And anyone who

persists in mixing the two will first of all ruin his artistic ability

in eurythmy and secondly find himself unable to achieve anything of

importance in respect to its hygienic-therapeutic element. Apart from

this it will be necessary to acquire certain physiological knowledge

— which will transform itself into a sort of feeling for the

processes forming the human organism — in order to apply the

hygienic-therapeutic side of eurythmy practically, as we will see in

the following lectures.

Now, having

given this preface, I would like to speak more specifically about what

may be considered the basis for human eurythmy itself since it appears

to me to be pertinent to the goals we wish to attain. If one wishes

to understand what eurythmy in its most varied aspects is, one must

first of all gain a certain understanding of the human larynx. We will

come to know the other vocal organs of man precisely through the course

of our exercises relating to it. But the first thing which we must obtain

will be a certain knowledge of the human larynx and its importance for

the human organization in general. There is much too strong a tendency

to regard each human organ as a thing unto itself. That isn't the case,

however. That is not how a human organ is. Every human organ is a member

of the organization as a whole and, at the same time, a metamorphic

variation of certain other organs. Basically, every self-contained human

organ is a metamorphosis of other self-contained human organs.

Nevertheless, the case is that certain human organs and groups of organs

prove to carry this metamorphic character more exactly within them, more

precisely, I would like to say, and others less precisely.

An example of an

organ where one can penetrate through that one organ into the essence

of the human organism solely through a properly understood metamorphosis

is the larynx. Recall from your anatomical and physiological knowledge

how peculiarly the human larynx is formed.

What I

wish to convey can be grasped only through Goetheanistic contemplation

of the human larynx. However, if you will make the effort to attain

to this Goetheanistic contemplation of the organs involved to which

we will now direct our attention, you will see that it is possible.

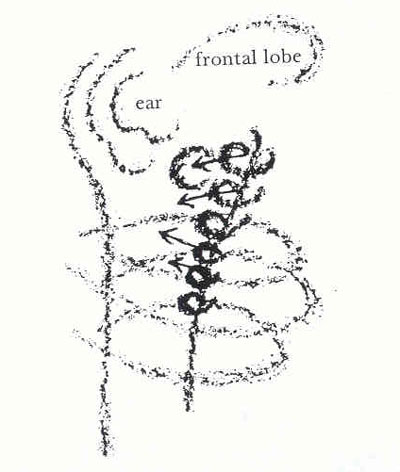

If you take the larynx first of all as an upwards directed extension

of the windpipe, you will discover when you study its forms that it

may be characterized as a reversed, a from front-to-back reversed piece

of the human organism; from another place, another piece of the human

organization turned around. Picture to yourself the back of the human

head, including the auricular parts, and think of what you are picturing

to yourself as the back of the human head, including the auricular parts

— insofar as these are localized in this part of man —

excluding the frontal lobe

[ 1 ]

for the moment, and extending downwards

so that it becomes the human ribcage with its vertebrae, including

the beginnings of the ribs which have the much softer breast bone to

the front that falls away altogether lower down. Picture to yourself,

then, this less clearly defined — system of organs that I have

presented to you: the posterior part of the head including the auditory

parts, broadening out into the ribcage below.

And now

think of this part somewhat transformed; imagine the diameter of the

ribs greatly reduced. Imagine that which is very wide in the ribs, in

the ribcage, here transformed into a pipe, the bony material being replaced

by cartilage. That part which I isolated as the head, imagine that to

be filled out in such a way that the less well filled out parts of the

head, were poured out, and then that what is now filled in with thicker

tissue were left out; think of that which in the head is actually filled

with a liquid solid mass replaced. When you imagine this transformation

of these parts of the human organism, then you have the metamorphosis

of the larynx: the posterior head with the attached ribcage, reversed.

The upwards extension into the larynx is truly a sort of posterior head,

transformed. It is actually so: the etheric formative forces of the

larynx bring about an inversion when we compare them with the formative

forces of the aforementioned part of the posterior head with the attached

ribcage. Considering the matter etherically, we carry in our breast,

in the larynx, a second man, in a manner of speaking, who is, to be

certain, in a way rudimentary, but who is in his dispositions, in his

beginnings nevertheless at a certain stage of development.

If that

which I have just described to you were to be turned around again to

its former position so as to appear as the posterior head, then it would,

in accordance with the formative forces, of necessity add on those parts

of the brain lying further forwards. The tendency to build something

similar on is also present in the larynx. The larynx has for this reason

the thyroid gland in its neighborhood. What appears in more recent

physiology as the peculiar conditions of the thyroid can be understood

metamorphically, if you can see a sort of decadent frontal lobe in the

thyroid which to a certain extent performs functions taken over from the

frontal lobe in the speaking man. The thyroid must co-operate with the

frontal lobe. If the thyroid is in any way diseased, you can easily

imagine what sort of conditions arise; simply because he has the thyroid,

man is organized to use it as an additional organ of thought related more

to his breast being.

That which

I have designated as etheric formative forces which are at work to bring

this second man, who takes up an appositive position in us, into being:

— these etheric formative forces are in fact very differentiated.

When we breathe and this breathing expresses itself in speaking or singing,

when this modified breathing (for from a certain point of view one must

call it that) lives as speech or song, then that whole system of organs

in man, which I have already indicated as the posterior head continuing

down into the breast, is in such inner movement, that this movement

experiences its reflexes in the organization of the larynx. So we must

picture to our-selves that this whole system — that together with

the ear is nothing other than a larynx, only metamorphosed — there

is a frontal lobe — calls forth certain effects which are reflected.

Thus our larynx performs backwards, in eurythmy, in the form of forces,

what we think, feel and so on. This eurythmy really goes on within us.

Our larynx eurythmizes; and we have then the assignment to turn around

again that which arises sensibly-supersensibly through the reflex-reaction

of the larynx, and to make it visible, so that our arms bring to expression

that which has already been relayed forth and back again. Thus we have to

do here with something which is taken directly from the human organism.

| |

Diagram 1

Click image for large view | |

One must

make it clear to oneself that we are drawing attention to that organ

which like an additional head with a downward extension has been set

into the rhythmic system. Our ordinary head, the more or less thoughtful

head, has the peculiarity of quieting down what pulses up rhythmically

into it through the arachnoidal cavity, which is an extension of the

respiratory system. It is by means of the transformation of the movement

from below in the rhythmic system into quiet; and by virtue of the fact

that a state of balance is reached and stasis is developed out of elements

in movement, reciprocally conditioning each other in motion, that thinking

is conditioned: through statics arising in the head out of the

dynamics.

The reverse

is also true: what we develop in the quiet, in the stasis of the head,

influences the dynamic of the rhythmic man, to begin with in a retardative

manner. The fact is that an unnatural exertion of the soul-spiritual

in connection with the head tends to slow down the circulation. A further

consequence is that chaotic or sloppy thinking transforms the rhythmic

into the arhythmic, changes the natural rhythm which should play in

the human rhythmic system into arhythm, even into an antirhythm when

it comes to full expression. And if one wishes to understand man, one

must observe the connection between the circulatory and respiratory

system, and careless, chaotic thought, as well as logical thought, Logical

thinking as such carries within it the tendency to slow down the rhythm.

Logical thought has the peculiarity of falling out of rhythm. Therefore,

the soul-life that wishes to fall into rhythm will try to supercede

logic and attempt to frame sentences and verses that follow not syntax,

but rhythm in their course. By striving to return to rhythm in poetry,

by resisting the enemy of poetry, that is prose (with the exception

of rhythmical prose, of course), one tries to become more human. I am

not claiming that through logic one's development will tend more towards

the animalic; when you wish, you can always imagine that one evolves

towards the angelic. But when one strives to turn back from the logical

towards the human, one must try to bring into the succession of the

syllables and their movement, into the movement of the sounds and into

the sentence structure, not that which is demanded by the syntax, but

that which the rhythm requires. We must pay heed to the rhythmic man

when we want to return to the realm of poetry; we should listen to the

head-man when we wish to enter into prose.

This will

serve as an indication of the connection which in fact exists between

that manifest part of man which I have described and that part which,

as a metamorphosis of it, is somewhat concealed. He is there within us,

however, this eurythmist who performs as the etheric body of the larynx

a distinct eurythmy intimately connected with the normal development of

our respiratory system, with our whole circulatory system and, naturally,

through the intermediary of the circulatory system even with the metabolic

system, as you can surmise from all that I have presented to you.

Now all

possible sorts of occasions arise for this very complicated arrangement,

this dove-tailing of a forwards- and a backwards-orientated system,

to become disjointed. It would be accurate to say that they are properly

articulated in only very few people of today's culture. It will be

necessary to develop a certain ability to observe this since when the

head system, for example, has been so dealt with in childhood that the

transgression against the rhythmic system is too great everything

possible can develop in later years simply through an irregularity

in what I have described. This is precisely because in the case of the

human organism, as in an avalanche, small provocations may build up to

great effects.

In observing

children from this aspect one will find that it is extremely significant

to what degree their unconscious living in rhythm predominates in their

soul-life over the quieting element of the head organization; for example

if this is the case, if the rhythmic system predominates, one must ask

oneself if something should not be introduced into the education of

the child. If in time the condition appears to he habitual, then something

must be clone. When, as a result of the anomaly to which I have drawn

attention, the child becomes increasingly excited, ever more and more

fluttery and one can do nothing with him, one must attempt to bring

an iambic element into his whole organization. This can be done by having

the child move in such a manner that, in full consciousness —

and for that he must have your guidance — he moves first the left

arm and the left hand forwards, thereafter the right arm, so that this

becomes the more conscious. The child must be aware: that is the first

and was the first. Throughout the entire exercise the consciousness

must prevail: that was the first and remains the first; it began with

the left. One can reinforce the whole affair by having the child walk,

stepping out with the left leg and bringing the right leg up to it,

so that the leg and foot exercise is added to the hand and arm exercise,

but only as a reinforcement, however. The arm exercise is really the

essential. If one has the child practise in this iambic manner, as one

may call it, one will see that the exercises will calm the fluttery

child, the excited child and so on provided they are continued over

a sufficiently long period of time.

Out of

your knowledge of eurythmy you could describe it thus:

[ 2 ]

You have the child make half an “A” with the left arm and

then complete this half “A” to a whole “A” with

the right arm, and so on, so that the child remains in motion and the

“A” does not come into being all at once, but as the result

of successive movements.

If on

the other hand one has a child who is phlegmatic, who doesn't want to

take things in — our Waldorf teacher know these children well,

they can at times bring one to mild despair; they actually hear nothing

of what one says to them, everything passes them by — in this

case one would do well to treat this child trochaically, that is to say,

in just the opposite manner. Naturally one cannot begin with everything

all at once; this is an element which has yet to he brought into Waldorf

education. One forms the “A” so that the child knows: first

the right arm, then the left arm, right arm, left arm and then further

that first the right leg is placed in front and the left leg brought

up to it; thus one has the arm movements forming the “A”

(one after the other) reinforced by the leg and foot movement. One must

pay particular attention that these things are done in such a way that

they live in the child's consciousness; so that the child is really

aware: on one occasion the left arm was the first, on the other the

right arm was the first.

You will

find that these things present difficulties for an inner understanding

if someone is in every way a physiologist in the modern sense and believes

that man's whole soul-life is mediated through the nervous system, that

is, if you do not know that feeling is mediated by the rhythmic system

and the will by the metabolic system, and that only thought formation

is mediated by the nervous system. If you do not know these things you

will have great difficulty in grasping the significance of what happens

in any part of the body, both in respect to the soul-spiritual part

and the bodily part of man's being.

The person

who has developed an ability to observe knows that when a person has

clumsy hand and finger movements and so on, he will exhibit a particular

manner of thinking as well which one can compare with what happens in

the fingers. It is really extremely interesting to study the connection

between the manner in which a person controls the mechanics of the arm

and the finger-physiognomy with the way in which he thinks. Then the

soul-spiritual qualities which a person portrays proceed from the whole

human being, not solely from the brain and nervous tissue. One must

learn to understand that one thinks not only with the brain but also

with the little finger and the big toe. There is a certain significance

in achieving lightness — particularly in the limbs — as

this will bring lightness into the soul-life as well. These ideas will

only become applicable — as we shall see in the following lectures

— when one has the possibility of providing a truly complete school

hygiene to accompany the other instruction. It can happen, for example,

that a child has the peculiarity of being unable to comprehend geometric

figures. He cannot understand a geometric figure by looking at it. However

difficult it may be you will do this child a great service when you

have him take a small pencil between the big toe and the next toe, hold

it and write really proper letters. That is something which carries

a certain significance and which points in a fully justified manner

to an inter-relationship in man.

Especially

in the case of children, one may notice that the three members of the

human organization do not snap properly into one another. A really large

part of the anomalies of life are due to this improper articulation. To

begin with, the children have headaches and at the same time one notices

that the digestion is disturbed and so on. The most varied conditions

may appear. We will give further indications in this regard in conjunction

with other exercises which will be shown in the next days. However,

when one is confronted with a situation such as I have described one

can achieve a great deal with the child or children through having them

do the following exercise: a eurythmic I — as you already know

— a eurythmic A and a eurythmic O; but so that the children make

the “I” with the whole upper body. For our physician friends

I want to emphasize particularly, that what is essential in eurythmy,

and that through which one achieves what is essential in artistic eurythmy

as well, is not the mere form of the limb in position seen from without,

but that which comes into being when the stretching or the bending within

the positioned limb is felt. What is felt in the limb is what is important.

Assume that you make an “I” with both arms; this

“I” will not appear as it should when seen from without if

you observe only its line, its content as a form. You must feel

concurrently and you can tell by looking at the person — that

he feels the stretching power in the I as he does it. Similarly when

a person makes an “E”, for example, the important thing is

not that he does this (crosses the arms), but that he feels: here one

limb comes to rest on the other. In this feeling of one limb on the

other lies the “E” in reality. And that which one sees in

the expression for this sensing of one limb through the other. Then what

you do here is no different from what you do when you look. You are

continually carrying out an “E” by crossing the axis of the

right eye with the axis of the left in order to find a point and so

arrive at a crossed line. That is actually “the primeval E”.

What has been demonstrated here is basically an imitation of it; however,

everything in man is a metamorphosis, and this is a perfectly justifiable

imitation, as in speaking “E” the larynx carries out exactly

the same form to the rear in the etheric.

When you practise

this exercise with a child it is necessary that the “I” be

done with the upper body, that is to say, the child stretches out his

upper body. He feels the whole body stretched. He makes the “A”

with his legs and the “O” by moving his arms so. have the

child do the following as quickly as possible in sequence: stretch the

upper body vertically, separate the legs, and make the “O”

movement with the arms; release and repeat, release and repeat and so

on. One can practise such a thing with the children in chorus, of course.

However, in principle such exercises should not be practised with the

children as a class. Artistic eurythmy and the eurythmy for pedagogic

and didactic reasons should be done by a class as a whole, for here

children of the same age belong together. In order to make the transition

from the usual class eurythmy to these matters related to

hygienic-therapeutic eurythmy, one must take those children out of

various classes who, due to the peculiarities which I have described

— the disharmony of

the three members of the human organism — have need of such an

exercise, in order to practise with them. One can take them out of the

most varied classes and then practise this exercise with those particularly

suited for it. That really must be done if one truly wishes to pursue

hygienic eurythmy, therapeutic eurythmy, in the school. Thus we are

already on the path which as we follow it further will lead us to study

certain movements that are actually only metamorphoses of the usual

eurythmic movements and to trace their effect on the human organization.

The fact is that we have organs in our interior and these organs have

certain forms. These forms may he subject to anomalies. The form of

each organ stands in a certain relationship to a possible form of movement

of the outer man. Therefore the following may be said. Let us assume

that some organ, let us say the gall, has the tendency to deformation,

a tendency to assume an abnormal form. A form of movement exists which

will counteract this tendency. And such is the case with every organ.

It is

in this direction that we intend to develop what will follow. What I

have given today was meant as an introduction to guide you to the path

leading into this subject.

Notes:

1. Vorderhirn; literally, the

frontal lobe of the brain

2. The sounds are given throughout

the English text as they are written in German: German “a”,

“ah” as in English “father”, German

“e”, “a” as in English “say”; German

“i”, “ee” as in English “feet”;

German “ei”, “i” as in English

“light”; German “au”, “ow” as in

English “how”; German “eu”, “oi”

as in English “joy”.

|