|

IV

I have frequently referred recently to the connection the course of

the year has with various aspects of human life, and during the Easter

days I pointed especially to the connection with the celebration of

festivals. Today I should like to go back to very ancient times and

say more on this subject, just in relation to the ancient Mysteries.

This can perhaps deepen in one way or another what we have spoken of

before.

To the people of very ancient periods on Earth, the festivals that

took place during the year formed a very significant part of their

lives. We know that in those ancient times the human consciousness

worked in an entirely different way from that of later times. We might

ascribe a somewhat dreamy nature to this old form of consciousness.

And indeed it was out of this dream condition that those insights

arose in the human soul, in the human consciousness, which then took

on the form of myths and in fact became mythology.

Through this dreamy, or we can also say instinctively clairvoyant

consciousness people saw more deeply into the spiritual environment.

But precisely through this more intensive kind of participation, not

just in the sensible workings of Nature, as is the case today, but

also in the spiritual events, people were all the more involved with

the phenomena connected with the cycle of the year, with the differing

aspects of Nature in spring and in autumn. I have pointed to this just

in recent days.

Today I want to share something entirely different with you in this

regard, and that is, how the festival of Midsummer, which has become

our St. John's festival, and the Midwinter festival, which has become

our Christmas, were celebrated in connection with the old Mystery

teachings. To begin with, we must be quite clear that the humanity of

the ancient times of which we are speaking did not have a full

ego-consciousness, as we do today. In the dreamlike consciousness, a

full ego-consciousness was lacking; and when this is the case, people

do not perceive precisely that which present-day humanity is so proud

of. Thus the people of that period did not perceive what existed in

dead nature, in the mineral nature.

Let us keep this firmly in mind, my dear friends: It was not a

consciousness that flowed along in abstract thoughts, but it lived in

pictures; yet it was dreamlike. These people entered into, for

example, the sprouting, burgeoning plant-life and plant-nature in

spring far more than is the case today. Again, they felt the shedding

of the leaves, their drying up in autumn, the whole dying away of the

plant world; felt deeply also the changes the animal world lived

through during the course of the year; felt the whole human

environment to be different when the air was filled with butterflies

fluttering and beetles humming. They felt their own human weaving in a

certain way as being alongside the weaving and being of the plants and

animal existence. But they not only had no interest, they had no

proper consciousness for the mineral realm, for the dead world outside

them. This is one side of the earlier human consciousness.

The other side is this: that no interest existed among this ancient

humanity for the form of man in general. It is very difficult

today to imagine what the human perception was in this regard, that

people in general took no particular interest in the human figure as a

space-form. They had, however, an intense interest in what pertains to

race. And the farther back we go into ancient cultures, the less do we

find people with the common consciousness interested in the human

form. On the other hand, they were interested in the color of the

skin, in the racial temperament. This is what people noticed. On the

one side man was not interested in the dead mineral world, nor, on the

other, in the human form. There was an interest, as we have said, in

what pertains to race, rather than in the universally human, including

the outer form of man.

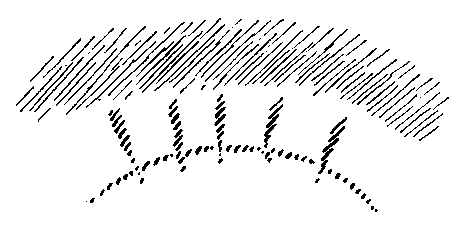

The great teachers of the Mysteries simply accepted this as a fact.

How they thought about it, I will show you graphically in a drawing.

They said to themselves: “The people have a dreamlike

consciousness by means of which they perceive very clearly the plant

life in their environment.” — In their dream-pictures these

people indeed lived with the plant life; but their dream consciousness

did not extend to the comprehension of the mineral world. So the

Mystery teachers said to themselves: “The human consciousness

reaches on the one side to the plant life [see drawing], which

is dreamily experienced, but not to the mineral; this lies outside

human consciousness. And on the other side, men feel within them what

still binds them with the animal world, that is, what pertains to

race, what is typical of the animal. [See drawing]. On the

other hand, what makes man really man, his upright form, the space

form of his being, lies outside of human consciousness.”

Thus, the specifically human lay outside the interest of these people

of ancient times. We can characterize the human by thinking of it, in

the sense of this ancient humanity, as enclosed within this space

[shaded portion in drawing], while the mineral and the

specifically human lay outside the realm of knowledge generally

accessible to those people who carried on their lives outside the

Mysteries.

But what I have just said applies only in general. With his own

forces, with what man experienced in his own being, he could not

penetrate beyond this space [see drawing], to the mineral on

the one side, to the human on the other. But there were ceremonies

originating in the Mysteries which brought to man in the course of the

year something approximating the human ego-consciousness on the one

side and the perception of the general mineral kingdom on the other.

Strange as it may sound to people of the present time, it is

nevertheless true that the priests of the ancient Mysteries arranged

festivals by whose unusual effects man was lifted out above the

plant-like to the mineral, and thereby at a certain time of year

experienced a lighting up of his ego. It was as if the ego shone into

the dream-consciousness. You know that even in a person's dreams

today, one's own ego, which is then seen, often constitutes an element

of the dream.

And so at the time of the St. John's festival, through the ceremonies

that were arranged for those among the people who wanted to take part

in them, ego-consciousness shone in just at the height of summer. And

at this time of midsummer people could perceive the mineral realm at

least to the extent necessary to help them attain a kind of

ego-consciousness, whereby the ego appeared as something that entered

into dreams from outside. In order to bring this about, the

participants in the oldest midsummer festivals — those of the

summer solstice which have become our St. John's festival — the

participants were led to unfold a musical-poetic element in round

dances having a strong rhythmic quality and accompanied by song.

Certain presentations and performances were filled with distinctive

musical recitative accompanied by primitive instruments. Such a

festival was completely immersed in the musical-poetic element. What

man had in his dream-consciousness he poured out into the cosmos, as

it were, in the form of music, in song and dance.

Modern man can have no true appreciation of what was accomplished by

way of music and song during those intense and widespread folk

festivals of ancient times, which took place under the guidance of men

who in turn had received their guidance from the Mysteries. For what

music and poetry have come to be since then is far removed from the

simple, primitive, elemental form of music and poetry which was

unfolded in those times at the height of summer under the guidance of

the Mysteries. For everything the people did in performing their

round-dances, accompanied by singing and primitive poetic recitations,

had the single goal of bringing about a soul mood in which there

occurred what I have just called the shining of the ego into the human

spirit.

But if those ancient people had been asked how they came to form such

songs and such dances, by means of which there could arise what I have

described, they would have given an answer highly paradoxical to

modern man. They would have said, for example: “Much of it has

been given to us by tradition, for those who went before us have also

done these things.” But in certain ancient times they would have

said: “One can learn these things also today without having any

tradition, if one simply develops further what manifests itself. One

can still learn today how to make use of instruments, how to form

dances, how to master the singing voice” — and now comes the

paradox in what these ancient people would have said. They would have

said: “It is learned from the songbirds.” — For

they understood in a deep way the whole import of the songbirds'

singing.

My dear friends, mankind has long ago forgotten why the songbirds

sing. It is true that men have preserved the art of song, the art of

poetry, but in the age of intellectualism in which the intellect has

dominated everything, they have forgotten the connection of singing

with the whole universe. Even someone who is musically inspired, who

sets the art of music high above the commonplace, even such a man,

speaking out of this later intellectualistic age, says: “I sing

as the bird sings who dwells in the branches. The song that issues

from my throat is my reward, and an ample reward it is.” Indeed,

my dear friends, the man of a certain period says this. The bird,

however, would never say such a thing. He would never say: “The

song that issues from my throat is my reward.” And just as little

would the pupils of the ancient Mystery schools have said it. For when

at a certain time of year the larks and the nightingales sing, what is

thereby formed streams out into the cosmos, not through the air, but

through the etheric element; it vibrates outward in the cosmos up to a

certain boundary... then it vibrates back again to Earth, to be

received by the animal realm — only now the divine-spiritual

essence of the cosmos has united with it.

And thus it is that the nightingales and the larks send forth their

voices into the universe (red) and that what they thus send

forth comes back to them etherically (yellow), for the time

during which they do not sing;

but in the meantime it has been filled with the content of the

divine-spiritual. The larks send their voices out over the cosmos, and

the divine spiritual, which takes part in the forming, in the whole

configuration of the animal kingdom, streams back to the Earth on the

waves of what had streamed out in the songs of the larks and the

nightingales.

Therefore if anyone speaks, not from the standpoint of the

intellectualistic age, but out of the truly all-encompassing human

consciousness, he really cannot say: “I sing as the bird sings

who dwells in the branches. The song that issues from my throat is my

reward, and an ample reward it is.” Rather, he would have to say:

“I sing as the bird sings who dwells in the branches. And the

song which streams forth from his throat into the cosmic expanses

returns to the Earth as a blessing, fructifying the earthly life with

divine spiritual impulses which then work on in the bird world and

which can only work in the bird world because they find their way in

on the waves of what has been ‘sung out’ to them into the

cosmos.”

Now of course not all creatures are nightingales and larks; also of

course not all of them send out song; but something similar even

though it is not so beautiful, goes out into the cosmos from the whole

animal world. In those ancient times this was understood, and

therefore the pupils of the Mystery-pupils were instructed in such

singing and dancing as they could then perform at the St. John's

festival, if I may call it by the modern name. Human beings sent this

out into the cosmos, of course not now in animal form, but in

humanized form, as a further development of what the animals send out

into cosmic space.— And there is something else yet that belonged

to those festivals: not only the dancing, the music, the song, but

afterward, the listening. First, there was the active

performance in the festivals; then the people were directed to listen

to what came back to them. For through their dances, their singing,

and all that was poetic in their performances, they had sent forth the

great questions to the divine spiritual of the cosmos. Their

performance streamed up, as it were, into cosmic spaces as the water

of the earth rises, forming clouds above and dropping down again as

rain. Thus, the effects of the human festival performances arose and

came back again — of course not as rain, but as something which

manifested itself to man as ego-power. And the people had a

sensitive feeling for that particular transformation which took place

in the air and warmth around the Earth, just about the time of the St.

John's festival. Of course the man of the present intellectualistic

age disregards anything like this. He has something else to do than

people of olden times. In these times, as also in others, he has to go

to five o'clock teas, to coffee parties; he has to attend the theater,

and so on; he simply has something else to do which is not dependent

on the time of year. In the doing of all this, man forgets that

delicate transformation which takes place in the Earth's atmospheric

environment.

But these people of olden times did feel how different the air and

warmth become around St. John's time, at the height of summer, how

these take on something of the plant nature. Just consider what kind

of a perception that was — this sensitive feeling for all that

goes on in the plant world. Let us suppose that this is the Earth, and

everywhere plants are coming out of the Earth.

The people then had a subtle feeling awareness of what is developing

there in the plant, of what lives in the plant. They had in the spring

a general feeling of nature, of which an after-echo is still retained

in our language. You will find in Goethe's Faust the expression

“es gruenelt” (It is beginning to get green). Who

notices nowadays when it is growing green, when the greenness rising

up out of the Earth in the spring, wells and wafts through the air?

Who notices when it grows green and when it blossoms? Well, of course

people see it today; the red and the yellow of the flowers

please them; but they do not notice that the air becomes quite

different when the flowers bloom, and again when the fruit is formed.

Such living participation in the plant world no longer exists in our

intellectualistic age, but it did exist for the people of ancient

times.

Hence they were aware of it in their perceptive feeling when the

“greening,” blooming and fruiting came toward them —

not now out of the Earth, but out of the surrounding atmosphere; when

air and warmth themselves streamed down from above like something akin

to plant nature (shaded in drawing). And when air and warmth

became thus plant-like, the consciousness of those people was

transported into that sphere in which the “I” then

descended, as answer to what they had sent out into the cosmos in the

form of music and poetry.

Thus the festivals had a wonderful, intimate, human content. This was

a question to the divine-spiritual universe. Men received the answer

because — just as we perceive the fruiting, the blossoming, the

greening of the Earth today — they felt something plant-like

streaming down from above out of the otherwise merely mineral air. In

this way there entered into the dream of existence, into the ancient

dreamy consciousness also the dream of the ego.

And when the St. John's festival was past and July and August came

again, the people had the feeling “We have an ego, but this ego

remains up there in heaven and speaks to us only at St. John's time.

Then we become aware that we are connected with heaven. It has taken

our ego into its protection. It shows it to us when it opens the great

window of heaven at St. John's time. But we must ask about it. We must

ask as we carry out the festival performances at St. John's time, as

in these performances we find our way into the unbelievably close and

intimate musical and poetic ceremonies.” — Thus these

ancient festivals already established a communication, a union,

between the earthly and the heavenly.

You see this whole festival was immersed in the musical, in the

musical-poetic. I might say that in the simple settlements of very

ancient peoples, suddenly, for a few days at the height of summer,

everything became poetic — although it had been thoroughly

prepared beforehand by the Mysteries. The whole social life was

plunged into this musical-poetic element. The people believed that

they needed this for life during the course of the year, just as they

needed daily food and drink; that they needed to enter into this mood

of dancing, music and poetry, in order to establish their

communication with the divine-spiritual powers of the cosmos. A relic

of this festival remained in a later age, when a poet said, for

example; “Sing, O Muse, of the wrath of Achilles, the son of

Peleus,” because he still remembered that once upon a time the

great question was put before the deity, and the deity was expected to

give answer to the question of men.

Just as these festivals at St. John's time were carefully prepared in

order to pose the great question to the cosmos so that the cosmos

might assure man at this time that he has an ego, which the heavens

have taken into their protection, so likewise was prepared the

festival at the time of the winter solstice, in the depths of winter,

which has now become our Christmas festival. But while at St. John's

time everything was steeped in the musical-poetic, in the dance

element, now in the depths of winter everything was first prepared in

such a way that the people knew they must become still and quiet, that

they must enter into a more contemplative element. And then there was

brought forth — in these ancient times of which outer history

provides no record, of which we can only know through spiritual

science — all that during the summer had been in the forming and

shaping and imaging elements which reached a climax in the festivals

in music and dance. During that time these ancient people, who in a

certain way went out of themselves in order to unite with the ego in

the heavens, were not involved in learning anything. Besides the

festival, they were occupied in doing what was necessary for their

subsistence. Instruction waited for the winter months, and this

reached its culmination, its festival expression, at the time of the

winter solstice, in the depth of winter, at Christmas time.

Then began the preparation of the people, again under the guidance of

pupils of the Mysteries, for various spiritual celebrations which were

not performed during the summer. It is difficult to describe in modern

terms what the people did from our September/October to our Christmas

time, because everything was so very different from what is done now.

But they were guided in what we would perhaps call riddle-solving, in

answering questions that were put in a veiled form so that people had

to discover a meaning in what was given in signs. Let us say that the

Mystery-pupils gave to those who were learning in this way some kind

of symbolic image, which they were to interpret. Or they gave what we

would call a riddle to be solved, or some kind of incantation. What

the magic saying contained, they were to apply to Nature, and thus

divine its meaning.

But especially there was careful preparation for what later took on

the most varied forms among the different peoples; for example, for

what was known in northern countries at a later time as the throwing

of the runic wands so that they formed shapes which were then

deciphered. People devoted themselves to these activities in the depth

of winter; but above all, those things were cultivated that then led

to a certain art of modeling, in a primitive form of course.

Among these ancient forms of consciousness was a most singular one,

paradoxical as it sounds to modern people, and it was as follows: With

the coming of October, an urge for some sort of activity began to stir

in people's limbs. In the summer a man had to accommodate the

movements of his limbs to what the fields demanded of him; he had to

put his hands to the plough; he had to adapt himself to the outer

world. When the harvest had been gathered in, however, and his limbs

were rested, then a need stirred in them for some other form of

activity, and his limbs took on a longing to knead. Then people

derived a special satisfaction from all kinds of plastic, moulding

activity. We might say that just as an intensive urge had arisen at

the time of the St. John's festival for dancing and music, so toward

Christmas time an intensive urge arose to knead, to mould, to create,

using any kind of pliant substance available in nature. People had an

especially sensitive feeling, for example, for the way water begins to

freeze. This gave them the specific impulse to push it in one

direction and another, so that the ice-forms appearing in the water

took on certain shapes. Indeed people went so far as to keep their

hands in the water while the shapes developed and their hands grew

numb! In this way, when the water froze under the waves their hands

cast up, it assumed the most remarkable artistic shapes, which of

course again melted away.

Nothing remains of all this in the age of intellectualism except at

most the custom of lead-casting on New Year's Eve, the Feast of St.

Sylvester. In this, molten lead is poured into water, and one

discovers that it takes on shapes whose meaning is then supposed to be

guessed. But that is the last abstract remnant of those wonderful

activities that arose from the impelling force in Nature experienced

inwardly by the human being, which expressed itself for example as I

have related: that a person thrust his hand into water which was in

process of freezing, the hand then becoming numb as he tested how the

water formed waves, so that the freezing water then

“answered” with the most remarkable shapes. In this way the

human being found the answers to his questions of the Earth.

Through music and poetry at the height of summer, he turned toward

the heavens with his questions, and they answered by sending

ego-feeling into his dreaming consciousness. In the depth of winter he

turned for what he wanted to know not now toward the heavens, but to

the earthly, and he tested what kind of forms the earthly element can

take on. In doing this he observed that the forms which emerged had a

certain similarity to those developed by beetles and butterflies. This

was the result of his contemplation. From the plastic, formative

element that he drew out of the nature processes of the Earth, there

arose in him the intuitive observation that the various animal forms

are fashioned entirely out of the earthly element. At Christmas man

understood the animal forms. And as he worked, as he exerted his

limbs, even jumped into the water and made certain movements, then

sprang out and observed how the solidifying water responded, he

noticed in the outer world what sort of form he himself had as man.

But this was only at Christmas time, not otherwise; at other times he

had a perception only of the animal world and of what pertains to

race. At Christmas time he advanced to the experience of the human

form as well.

Just as in those times of the ancient Mysteries the ego-consciousness

was mediated from the heavens, so the feeling for the human form was

conveyed out of the Earth. At Christmas time man learned to know the

Earth's form-force, its sculptural shaping force; and at St. John's

time, at the height of summer he learned to know how the harmonies of

the spheres let his ego sound into his dream-consciousness.

And thus at special festival seasons the ancient Mysteries expanded

the being of man. On the one side the environment of the Earth

extended out into the heavens, so that man might know how the heavens

held his “I” in their protection, how his “I”

rested there. And at Christmas time the Mystery teachers caused the

Earth to give answer to the questioning of man by way of plastic

forms, so that man gradually came to have an interest in the human

form, in the flowing together of all animal forms into the human form.

At midsummer man learned to know himself inwardly, in relation to his

ego; in the depth of winter he learned to feel himself outwardly, in

relation to his human form. And so it was that what man perceived as

his being, how he actually felt himself, was not acquired simply by

being man, but by living together with the course of the year; that in

order for him to come to ego-consciousness, the heavens opened their

windows; that in order for him to come to consciousness of his human

form, the Earth in a certain way unfolded her mysteries. Thus the

human being was inwardly intimately linked with the course of the

year, so intimately linked that he had to say to himself: “I know

about what I am as man only when I don't live along stolidly, but when

I allow myself to be lifted up to the heavens in summer, when I let

myself sink down in winter into the Earth mysteries, into the secrets

of the Earth.”

You see from this that at one time the festival seasons with their

celebrations were looked upon as an integral part of human life. A man

felt that he was not only an earth-being but that his essential being

belonged to the whole world, that he was a citizen of the entire

cosmos. Indeed he felt himself so little to be an earth-being that he

actually had first to be made aware of what he was through the Earth

by means of festivals. And these festivals could be celebrated only at

certain seasons because at other times the people who experienced the

course of the year to some degree would have been quite unable to

experience it at all. For all that the people could experience through

the festivals was connected with the related seasons.

Mark you, after man has once achieved his freedom in the age of

intellectualism, he can certainly not come again to this sharing in

the life of the cosmos in the same way that he experienced it in

primitive ages. But he can nevertheless come to it even with his

modern constitution, if he applies himself once more to the spiritual.

We might say that in the ego consciousness which mankind has had for a

long time now, something has been drawn in which could be attained

only through the windows of heaven in summer. But just for that reason

man must be learning to understand the cosmos, acquire for himself

something else which in turn lies beyond the ego. It is natural today

for people to speak of the human form in general. Those who have

entered into the intellectual age no longer have a strong feeling for

the animalistic-racial element. But just as this feeling formerly came

over man, I should like to say as a force, as an impulse, which could

be sought only out of the Earth, so today, through an understanding of

the Earth which cannot be gained by means of geology or mineralogy but

only once more in a spiritual way, man must come again to something

more than the mere human form.

If we consider the human form we can say: In very ancient times man

felt himself within this form in such a way that he felt only the

external racial characteristics connected with the blood, but failed

to perceive as far as the skin itself (red in drawing); he did

not notice what formed his outline.

Today man has come so far that he does notice his outline, his bodily

limits. He perceives his contour indeed as the typically human feature

of his form (blue). Now, however, man must come out beyond

himself; he must learn to know the etheric and astral elements outside

himself. This he can do only through the deepening of spiritual

science.

Thus we see that our present-day consciousness has been acquired at

the cost of losing much of the former connection of our consciousness

with the cosmos. But once man has come to experience his freedom and

his world of thought, then he must emerge again and experience

cosmically.

This is what Anthroposophy intends when it speaks of a renewal of the

festivals, even of the creating of festivals like the Michael festival

in autumn of which we have recently spoken. We must come once more to

an inner understanding of what the cycle of the year can mean to man

in this connection; it can then be something even loftier than it was

for man long ago, as we have described it.

|