THE ORGANISATION OF THE WALDORF SCHOOL

When we speak of organisation to-day we commonly imply that something

is to be organised, to be arranged. But in speaking of the

organisation of the Waldorf School I do not and cannot mean it in this

sense, for really one can only organise something which has a

mechanical nature. One can organise the arrangements in a factory

where the parts are bound into a whole by the ideas which one has put

into it. The whole exists and one must accept it as an organism. It

must be studied. One must learn to know its arrangements as an

organism, as an organisation.

A school such as the Waldorf School is an organism in this sense, as a

matter of course, — but it cannot be organised, as I said before

in the sense of making a program laying down in paragraphs how the

school shall be run: Sections: 1, 2, 3, etc. As I said, I am fully

convinced — and I speak without irony — that in these days

if five or twelve people sit down together they can work out an ideal

school plan, not to be improved upon, people are so intelligent and

clever nowadays: Paragraphs 1, 2, etc., up to 12 and so on; the only

question which arises is: can it be carried out in practice? And it

would very soon be apparent that one can make charming programs, but

actually when one founds a school one has to deal with a finished

organism.

This school, then, comprises a staff of teachers; and they are not

moulded out of wax. Your section 1 or section 5 would perhaps lay

down: the teacher shall be such and such. But the staff is not

composed of something to be moulded like wax, one has to seek out each

single teacher and take him with the faculties which he has. Above all

it is necessary to understand what these faculties are. One must know

to start with, whether he is a good elementary teacher or a good

teacher for higher classes. It is as necessary to under-stand the

individual teacher as it is, in the human organism, to understand the

nose or the ear if one is to accomplish something. It is not a

question of having theoretical principles and rules, but of meeting

reality as it comes. If teachers could be kneaded out of wax then one

could make programs. But this cannot be done. Thus the first reality

to reckon with is the college of teachers. And this one must know

intimately. Thus it is the fundamental principle of the organisation

of the Waldorf School that, since I am the director and spiritual

adviser to the Waldorf School, I must know the college of teachers

intimately, in all its single members, I must know each single

individuality.

The second thing is the children, and here at the start we were faced

with certain practical difficulties in the Waldorf School. For the

Waldorf School was founded in Stuttgart by Emil Molt from the midst of

the emotions and impulses of the years 1918 and 1919, after the end of

the war. It was founded, in the first place as a social act. One saw

that there was not much to be done with adults as far as social life

was concerned; they came to an understanding for a few weeks in middle

Europe after the end of the war. After that, they fell back on the

views of their respective classes. So the idea arose of doing

something for the next generation. And since it happened that Emil

Molt was an industrialist in Stuttgart, we had no need to go from

house to house canvassing for children, we received the children of

the workers in his factory. Thus, at the beginning, the children we

received from Molt's factory, about 150 of them, were essentially

proletarian children. These 150 children were supplemented by almost

all the anthroposophical children in Stuttgart and the neighbourhood;

so that we had something like 200 children to work with at the

beginning.

This situation brought it about that the school was practically

speaking a school for all classes (Einheitschule). For we had a

foundation of proletarian children, and the anthroposophical children

were mostly not proletarian, but of every status from the lowest to

the highest. Thus any distinctions of class or status were ruled out

in the Waldorf School by its very social composition. And the aim

through-out has been, and will continue to be, solely to take account

of what is universally human. In, the Waldorf School what is

considered is the educational principles and no difference is made in

their application between a child of the proletariat and a child of

the ex-Kaiser — supposing it to have sought entry into the

school. Only pedagogic and didactic principles count, and will

continue to count. Thus from the very first, the Waldorf School was

conceived as a general school.

But this naturally involved certain difficulties, for the proletarian

child brings different habits with him into the school from those of

children of other status. And these contrasts actually turned —

out to be exceedingly beneficial, apart from a few small matters which

could be got over with a little trouble. What these things were you

can easily imagine; they are mostly concerned with habits of life, and

often it is not easy to rid the children of all they bring with them

into the school. Although even this can be achieved if one sets about

it with good will. Nevertheless, many children of the so-called upper

classes, unaccustomed to having this or that upon them, would

sometimes carry home the unpleasant thing, whereupon unpleasant

comments would be made by their parents.

Well, as I said, here on the other hand were the children. These were

what I might call the tiny difficulties. A greater difficulty arose

from the fact that the ideal of the Waldorf School was to educate

purely in accordance with knowledge of man, to give the child week by

week, what the child's own nature demanded.

In the first instance we arranged the Waldorf School as an elementary

school of 8 classes, so that we had in it children from 6 or 7 to 14

or 15 years old. Now these children came to us at the beginning from

all kinds of different schools. They came with previous attainments of

the most varied kinds; certainly not always such as we should have

considered suitable for a child of 8 or 11 years old. So that during

the first year we could not count on being able to carry out our ideal

of education; nor could we proceed according to plan: 1, 2, etc., but

we had to proceed in accordance with the individualities of the

children we had in each particular class. Nevertheless this would only

have been a minor difficulty. The greater difficulty is this, that no

method of education however ideal it is must tear a man out of his

connections in life. The human being is not an abstract thing to be

put through an education and finished with, a human being is the child

of particular parents. He has grown up as the product of the social

order. And after his education he must enter this social order again.

You see, if you wanted to educate a child strictly in accordance with

an idea, when he was 14 or 15 he would no doubt be very ideal, but he

would not find his place in modern life, he would be quite at sea.

Thus it was not merely a question of carrying out an ideal, nor is it

so now in the Waldorf School. The point is so to educate the child

that he remains in touch with present-day life, with the social order

of to-day. And here there is no sense in saying: the present social

order is bad. Whether it be good or bad, we simply have to live in it.

And this is the point, we have to live in it and hence we must not

simply withdraw the children from it. Thus I was faced with the

exceedingly difficult task of carrying out an educational idea on the

one hand while on the other hand keeping fully in touch with

present-day life.

Naturally the education officers regarded what was done in other

schools as a kind of ideal. It is true they always said: one cannot

attain the ideal, one can only do one's best under the circumstances.

Life demands this or that of us. But one finds in actual practice when

one has dealings with them that they regard all existing arrangements

set up either by state authorities or other authorities as

exceptionally good, and look upon an institution such as the Waldorf

School as a kind of crank hobby, a vagary, something made by a person

a little touched in the head.

Well you know, one can often let a crank school like this carry on and

just see what comes of it. And in any case it has to be reckoned with.

So I endeavoured to come to terms with them through the following

compromise. In a memorandum, I asked to he allowed three years grace

to try out my ‘vagary,’ the children at the end of that

time, to be sufficiently advanced to be able to enter ordinary

schools. Thus I worked out a memorandum showing how the children when

they had been taken to the end of the third elementary class, namely

in their 9th year, should have accomplished a certain stage, and

should be capable of entering the 4th class in another school. But

during the intermediate time, I said, I wanted absolute freedom to

give the children week by week, what was requisite according to a

knowledge of man. And then I requested to have freedom once more from

the 9th to the 12th year. At the end of the 12th year the children

should have again reached a stage such as would enable them to enter

an ordinary school; and the same thing once again on their leaving

school. Similarly with regard to the children, — I mean, of

course, the young ladies and gentlemen — who would be leaving

school to enter college, a university or any other school for higher

education: from the time of puberty to the time for entering college

there should be complete freedom: but by that time they should be far

enough advanced to be able to pass into any college or university

— for naturally it will be a long time before the Free High

School at Dornach will be recognised as giving a qualification for

passing out into life.

This arrangement to run parallel with the organisation of ordinary

schools was an endeavour to accord our own intentions and convictions

with things as they are, to make a certain harmony. For there is

nothing unpractical about the Waldorf School, on the contrary, on

every point this ‘vagary’ aims at realising things which

have a practical application to life.

Hence also, there is no question of constructing the school on the

lines of some bad invention — then indeed it would be a

construction, not an organisation, — but it is truly a case of

studying week by week the organism that is there. Then an observer of

human nature — and this includes child nature — will

actually light upon the most concrete educational measures from month

to month. As a doctor does not say at the very first examination

everything that must be done for his patient, but needs to keep him

under observation because the human being is an organism, so much the

more in such an organism as a school must one make a continuous study.

For it can very well happen that owing to the nature of the staff and

children in 1920 — say — one will proceed in a manner quite

different from one's procedure with the staff and children one has in

1924. For it may be that the staff has increased and so quite changed,

and the children will certainly be quite different. In face of this

situation the neatest possible sections 1 to 12 would be of no use.

Experience gained day by day in the classroom is the only thing that

counts.

Thus the heart of the Waldorf School, if I speak of its organisation,

is the teachers' staff meeting. These staff meetings are held

periodically, and when I can be in Stuttgart they are held under my

guidance, but in other circumstances they are held at frequent

intervals. Here, before the assembled staff, every teacher throughout

the school will discuss the experiences he has in his class in all

detail. Thus these constant staff meetings tend to make the school

into an organism in the same way as the human body is an organism by

virtue of its heart. Now what matters in these staff meetings is not

so much the principles but the readiness of all teachers to live

together in goodwill, and the abstention from any form of rivalry. And

it matters supremely that a suggestion made to another teacher only

proves helpful when one has the right love for every single child. And

by this I do not mean the kind of love which is often spoken about,

but the love which belongs to an artistic teacher.

Now this love has a different nuance from ordinary love. Neither is it

the same as the sympathy one can feel for a sick man, as a man, though

this is a love of humanity. But in order to treat a sick man one must

also be able — and here please do not misunderstand me — one

must also be able to love the illness. One must be able to speak of a

beautiful illness. Naturally for the patient it is very bad, but for

him who has to treat it it is a beautiful illness. It can even in

certain circumstances be a magnificent illness. It may be very bad

indeed for the patient but for the man whose task it is to enter into

it and to treat it lovingly it can be a magnificent illness.

Similarly, a boy who is a thorough ne'er-do-well (a ‘Strick’

as we say in German) by his very roguery, his way of being bad, of

being a ne'er-do-well can be sometimes so extraordinarily interesting,

that one can love him extraordinarily. For instance, we have in the

Waldorf School a very interesting case, a very abnormal boy. He has

been at the Waldorf School from the beginning, he came straight into

the erst class. His characteristic was that he would run at a teacher

as soon as he had turned his back, and give him a bang. The teacher

treated this rascal with extraordinary love and extraordinary

interest. He fondled him, led him back to his place, gave no sign of

having noticed that he had been banged from behind. One can only treat

this child by taking into consideration his whole heredity and

environment. One has to know the parental milieu in which he has grown

up, and one must know his pathology. Then, in spite of his rascality

one can effect something with him, especially if one can love this

form of rascality. There is something lovable about a person who is

quite exceptionally rascally.

A teacher has to look upon these things in a different way from the

average person. Thus it is very important for him to develop this

special love I have spoken of. Then in the staff meeting one can say

something to the point. For nothing helps one so much in dealing with

normal children as to have observed abnormal children.

You see healthy children are comparatively hard to study for in them

every characteristic is toned down. One does not so easily see how it

stands with a certain characteristic and what relation it has to

others. In an abnormal child, where one character complex predominates

one very soon finds the, way to treat this particular character

complex, even if it involves a pathological treatment. And this

experience can be applied to normal children.

Such then, is the organisation; and such as it is it has brought

credit to the Waldorf School in so far as the number of children has

rapidly increased; whereas we began the school with about 200 children

we now have nearly 700. And these children are of all classes, so that

the Waldorf School is now organised as a general school

[‘Einbeitschule.’]

in the best sense of the word. For most of the classes, particularly

in the lower classes, we have had to arrange parallel classes because

we received too many children for a single

class; thus we have a first class A, and a first class B and so on.

This has made, naturally, increasingly great demands on the Waldorf

School. For where the whole organisation is to be conceived from out

of what life presents, every new child modifies its nature; and the

organism with this new member requires a fresh handling and a further

study of man.

The arrangement in the Waldorf School is that the main lesson shall

take place in the morning. The main lesson begins in winter at 8 or

8:15, in summer a little earlier. The special characteristic of this

main lesson is that it does away with the ordinary kind of time table.

We have no time table in the ordinary sense of the word, but one

subject is taken throughout this erst two hour period in the morning

— with a break in it for younger children, — and this

subject is carried on for a space of four or six weeks and brought to

a certain stage. After that, another subject is taken. For children of

higher classes, children of 11, 12, or 13 years old what it comes to

is that instead of having: 8 – 9 Religion, 9 – 10 Natural

History, from 10 – 11 Arithmetic, — that is, instead of

being thrown from one thing to another, — they have for example,

in October four weeks of Arithmetic, then three weeks of Natural

History, etc.

It might be objected that the children may forget what they learn

because a comprehensive subject taken in this way is hard to memorise.

This objection must be met by economy in instruction and by the

excellence of the teachers. The subjects are recapitulated only in the

last weeks of the school year so as to gather up, as it were, all the

year's work. In this manner, the child grows right into a subject.

The language lesson, which, with us, is a conversation lesson, forms

an exception to this arrangement. For we begin the teaching of

languages, as far as we can, — that is English and French —

in the youngest classes of the school; and a child learns to speak in

the languages concerned from the very beginning. As far as possible,

also, the child learns the language without the meaning being

translated into his own language. (Translator's Note: i.e. direct

method). Thus the word in the foreign language is attached to the

object, not to the word in the German language. So that the child

learns to know the table anew in some foreign language, — he does

not learn the foreign word as a translation of the German word Tisch.

Thus he learns to enter right into a language other than his mother

tongue; and this becomes especially evident with the younger children.

It is our practice moreover to avoid giving the younger children any

abstract, theoretical grammar. Not until a child is between 9 and 10

years old can he understand grammar — namely, when he reaches an

important turning point of which I shall be speaking when. I deal with

the boys and girls of the Waldorf School.

This language teaching mostly takes place between 10 and 12 in the

morning. This is the time in which we teach what lies outside the main

lesson — which is always held in the first part of the morning.

(The Waldorf School began at 8 a.m.) Thus any form of religion

teaching is taken at this time. And I shall be speaking further of

this teaching of religion, as well as about moral teaching and

discipline, when I deal with the theme ‘the boys and girls of the

Waldorf School.’ But I want for the moment to emphasise the fact

that the afternoon periods are all used for singing, music and

eurhythmy lessons. This is so that the child may as far as possible

participate with his whole being in all the education and instruction

he receives.

The instruction and education can appeal the better to the child's

whole nature because it is conceived as a whole in the heart of the

teachers' meetings, as I have described. This is particularly

noticeable when the education passes over from the more psychic domain

into that of physical and practical life. And particular attention is

paid in the Waldorf School to this transition into physical and

practical life.

Thus we endeavour that the children shall learn to use their hands

more and more. Taking as a start, the handling little children do in

their toys and games, we develop this into more artistic crafts but

still such as come naturally from a child.

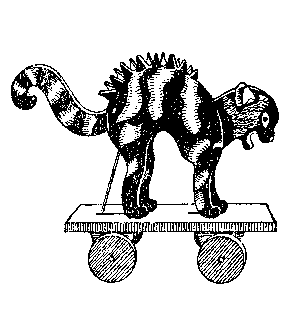

This is the sort of thing we produce (Tr. Note: showing toys etc.)

this is about the standard reached by the 6th school year. Many of

these things belong properly to junior classes, but as I said, we have

to make compromises and shall only be able to reach our ideal later on

— and then what a child of 11 or 12 now does, a child of 9 will

be able to do. The characteristic of this practical work is that it is

both spontaneous and artistic. The child works with a will on

something of his own choosing, not at a set task. This leads on to

handwork or woodwork classes in which the child has to carve and make

all kinds of objects of his own planning. And one discovers how much

children can bring forth where their education is founded in real

life. I will give an example. We get the children to carve things

which shall be artistic as well as useful. In this for instance: (Tr.

Note: holding up a carved wooden bowl) one can put things. We get the

children to carve forms like this so that they may acquire feeling for

form and shape sprung from themselves; so that the children shall make

something which derives its form from their own will and pleasure. And

this brings out a very remarkable thing.

Suppose we have taken human anatomy at some period with this class, a

thing which is particularly important for this class in the school

(VI). We have explained the forms of the bones, of the skeletal

system, to the children, also the external form of the body and the

functions of the human organism. And since the teaching has been given

in an artistic form, in the manner I have described, the children have

been alive to it and have really taken it in. It has reached as far as

their will, not merely to the thoughts in their heads. And then, when

they come to do things like this (Carved bowl) one sees that it lives

on in their hands. The forms will be very different according to what

we may have been teaching. It comes out in these forms. From the

children's plastic work one can tell what was done in the morning

hours from 8 – 10, because the instruction given permeates the

whole being.

This is achieved only when one really takes notice of the way things

go on in nature. May I say a very heretical thing: people are very

fond of giving children dolls, especially a ‘lovely’ doll.

They do not see that children really don't want it. They wave it away,

but it is pressed upon them. Lovely dolls, all painted! It is much

better to give children a handkerchief, or, if that can't be spared,

some piece of stuff; tie it together, make the head here, paint in the

nose, two eyes etc. — healthy children far prefer to play with

these than with ‘lovely’ dolls, because here is something

left over for their fantasy; whereas the most magnificent doll, with

red cheeks etc., leaves nothing over for the fantasy to do. The fine

doll brings inner desolation to the child. (Tr. Dr. Steiner

demonstrated what he was saying with his own pocket handkerchief.)

Now, in what way can we draw out of a child the things he makes? Well,

when children of our VIth class in the school come to

produce things from their own feeling for form, they look like this,

— as you can see from this small specimen we have brought with

us. (Wooden doll.) The things are just as they grow from the

individual fantasy of any child.

It is very necessary, however, to get the children to see as soon as

possible that they want to think of life as innately mobile not

innately rigid. Hence, when one is getting the child to create toys,

— which for him are serious things, to be taken in earnest,

— one must see to it that the things have mobility. You see a

thing like this — to my mind a most remarkable fellow —

(carved bear) — children do entirely themselves, they also put

these strings on it without any outside suggestion, — so that

this chap can wag his tongue when pulled: so (bear with attached

strings). Or children bring their own fantasy into play: they make a

cat, not just a nice cat, but as it strikes them: humped, without more

ado and very well carried out.

Click image for large view

I hold it to be particularly valuable for children to have to do, even

in their toys, with things that move, — not merely with what is

at rest, but with things which involve manipulation. Hence children

make things which give them enormous joy in the making. They do not

only make realistic things, but invent little fellows like these

gnomes and suchlike things (Showing toys).

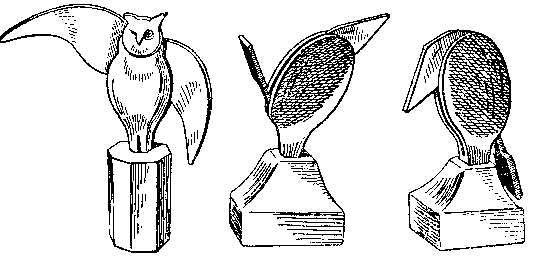

They also discover how to make more complicated things like this; they

are not told that this is a thing that can be made, only the child is

led on until he comes to make a lively fellow like this of his own

accord. (Movable raven. ‘Temperaments Vogel’) — now you

can see he looks very depressed and sad.

Click image for large view

(The head and tail of the temperament bird can be moved up or down.

Dr. Steiner had them both up at first, and then turned them both

down.)

And when a child achieves a thing like this (a yellow owl with movable

wings) he has wonderful satisfaction. These things are done by

children of 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14 years old. So far only these older

ones have done it, but we intend to introduce it gradually into the

younger classes, where of course the forms will be simpler.

Now we have further handwork lessons in addition to this handicraft

teaching. And here it should be borne in mind that throughout the

Waldorf School boys and girls are taught together in all subjects.

Right up to the highest class boys and girls are together for all

lessons. (durcheinandersitzen: i.e.=sit side by side, or beside each

other.) So that actually, with slight variations of course (and as we

build up the higher classes there will naturally have to be

differentiation) — but on the whole the boys actually learn to do

the same things as the girls. And it is remarkable how gladly little

boys will knit and crochet and girls do work that is usually only

given to boys. This has a social result also: Mutual understanding

between the sexes, a thing of the very first importance to-day. For we

are still very unsocial and full of prejudice in this matter. So that

it is very good when one has results such as I will now proceed to

show.

In Dornach we had a small school of this kind. Now in the name of

Swiss freedom it has been forbidden, and the best we can do is to

undertake the instruction of more advanced young ladies and gentlemen;

for Swiss freedom lays it down that no free schools shall exist in

competition with state schools. — Well, of course, such a thing

is not a purely pedagogical question. — But in Dornach we tried

for a time to run a small school of this nature, and in it boys and

girls did their work together. This is a boy's work; it was done in

Dornach by a little American boy of about nine years old. (Tea cosy;

Kaffee Warmer.) This is the work of a boy not a girl. And in the

Waldorf School, as I have said, boys and girls work side by side in

the handwork lessons. All kinds of things are made in handwork. And

the boys and girls work together quite peaceably. In these two pieces

of work, for instance, you will not be able to decide without looking

to the detail what difference is to be seen between boys' and girls'

work. (Two little cloths).

Now in the top classes which, at the present stage of our growth,

contain boys and girls of 16 and 17, we pass on to the teaching of

spinning and weaving as an introduction to practical life for the

children, so that they may make a con-tact with real life; and here in

this one sphere we find a striking difference: the boys do not want to

spin like the girls, they want to assist the girls. The girls spin and

the boys want to fetch and carry, like attendant knights. This is the

only difference we have found so far, that in the spinning lesson the

boys want to serve the girls. But apart from this we have found that

the boys do every kind of handwork.

You will observe that the aim is to build up the hand-work and

needlework lesson in connection with what is learned in the painting

lesson. And in the painting lesson the children are not taught to draw

(with a brush) or make patterns (‘Sticken’). But they learn

to deal freely and spontaneously with the element of colour itself.

Thus it is immensely important that children should come to a right

experience of colour. If you use the little blocks of colour of the

ordinary paint box and let the child dip his brush in them and on the

palette and so paint, he will learn nothing. It is necessary that

children should learn to live with colour, they must not paint from a

palette or block, but from a jar or mug with liquid colour in it,

colour dissolved in water. Then a child will come to feel how one

colour goes with another, he will feel the inner harmony of colours,

he will experience them inwardly. And even if this is difficult and

inconvenient — sometimes after the painting lesson the class-room

does not look its best, some children are clumsy, others not amenable

in the matter of tidiness — even if this, way does give more

trouble, yet enormous progress can be made when children get a direct

relation to colour in this way, and learn to paint from the living

nature of colour itself, not by trying to copy something in a

naturalistic way. Then colour mass and colour form come seemingly of

their own accord upon the paper. Thus to begin with, both at the

Waldorf School and at Dornach, what the children paint is their

experience of colour. It is a matter of putting one colour beside

another colour, or of enclosing one colour within other colours. In

this way the child enters right into colour, and little by little, of

his own accord he comes to produce form from out of colour. As you see

here, the form arises without any drawing intervening, from out of the

colour. (showing paintings by Dornach children). This is done by the

some-what more advanced children in Dornach, but the little children

are taught on the same principle in the Waldorf School Here, for

instance, we have paintings representative of the painting teaching in

the Waldorf School which shows the attempt to express colour

experience. Here, what is attempted, is not to paint some

thing, but to paint experience of colour. The painting of

something can come much later on. If the painting of something is

begun too soon a sense for living reality is lost and gives place to a

sense for what is dead.

If you proceed in this way, when you come to the treatment of any

particular object in the world it will be far livelier than it would

be without such a foundation. You see children who have previously

learned to live in the element of colour, can make the island of

Sicily, for instance, look like this, (coloured map) and we get a map.

In this way, artistic work is related to the geography teaching.

When the children have acquired a feeling for colour harmony in this

way they come on to making useful objects of different kinds. This is

not first drawn, but the child has acquired a feeling for colour, and

so later he can paint or shape such a thing as this book cover, or

folio. The important thing is to arouse in the child a real feeling

for life. And colour and form have the power to lead right into life.

Now sometimes you find a terrible thing done: the teacher will let a

child make a neckband, and a waist band and a dress hem, and all three

will have on them the very same pattern. You see this sometimes.

Naturally it is the most horrible thing in the world to an artistic

instinct. The child must be taught very early that a band designed for

the neck has a tendency to open downwards, it has a downward

direction; that a girdle or waistband tends in both directions, (i.e.

both upwards and downwards); and that the hem of the dress at the

bottom must show an upward tendency away from the bottom. Hence one

must not perpetrate the atrocity of teaching the child simply to make

an artistic pattern of one kind on a band, but the child must learn

how the band should look according to whether it is in one position or

another on a person.

Click image for large view

In the same way, one should know when making a book cover, that when

one looks at a book, and opens it so, there is a difference between

the top and the bottom. It is necessary that the child should grow

into this feeling for space, this feeling for form. This penetrates

right into his limbs. This is a teaching that works far more strongly

into the physical organism, than any work in the abstract. Thus the

treatment of colour gives rise to the making of all kinds of useful

objects; and in the making of these the child really comes to feel

colour against colour and form next to form, and that the whole has a

certain purpose and therefore I make it like this.

These things in all detail are essential to the vitality of the work.

The lesson must be a preparation for life. Now among these exhibits

you will find all sorts of interesting things. Here, for instance, is

something done by a very little girl, comparatively speaking.

I cannot show you everything in the course of this lecture, but I

would like to draw your attention to the many charming objects we have

brought with us from the Waldorf School. You will find here two song

books composed by Herr Baumann which will show you the kind of songs

and music we use in the Waldorf School. Here are various things

produced by one of the girls — since owing to the customs we

could not bring a great deal with us — in addition to our natural

selves. But all these things are carried out plasticly, are modelled,

as is shown here. You see the children have charming ideas: (apes);

they capture the life in things; these are all carved in wood.

(Showing illustrations of wood-carving by children of the Waldorf

School reproduced by one of the girls.)

You see here (maps) how fully children enter into life when the

principle from which they start is full of life. You can see this very

well in the case of these maps: first they have an experience of

colour and this is an experience of the soul. A colour experience

gives them a soul experience. Here you see Greece experienced in soul.

When the child is at home in the element of colour, he grows to feel

in geography: I must paint the island of Crete, the island of Candia

in a particular colour, and I must paint the coast of Asia Minor so,

and the Peleponesus so. The child learns to speak through colour, and

thus a map can actually be a production from the innermost depths of

the soul.

Think what an experience of the earth the child will have when this is

how he has seen it inwardly, when this is how he has painted Candia or

Crete or the Peleponesus or Northern Greece; when he has had the

feelings which go with such colours as these; then Greece itself can

come alive in his soul the child can awaken Greece anew from his own

soul. In this way the living reality of the world becomes part of a

man's being. And when you later confront the children with the dry

reality of everyday life they will meet it in quite a different way,

because they have had an artistic, living experience of the elements

of colour in their simple paintings, and have learned to use its

language.

|