Lecture Three

KOBERWITZ,

11th June, 1924.

MY DEAR FRIENDS,

The earthly and

cosmic forces, of which I have spoken, work in the farm through the

substances of the Earth, needless to say. In the next lectures we

shall pass on to various practical aspects, but before we can do so

we must enter a little more precisely into the question: How do these

forces work through the substances of the Earth? In the present

lecture we shall consider Nature's activity quite generally

speaking.

One of the most

important questions in agriculture is that of the significance of

nitrogen — its influence in all farm-production. This is

generally recognised; nevertheless the question, what is the essence

of nitrogen's activity, has fallen into great confusion nowadays.

Wherever nitrogen is active, men only recognise, as it were, the last

excrescence of its activities — the most superficial aspects in

which it finds expression. They do not penetrate to the relationships

of Nature wherein nitrogen is working, nor can they do so, so long as

they remain within restricted spheres. We must look out into the wide

spaces, into the wider aspects of Nature, and study the activities of

nitrogen in the Universe as a whole. We might even say — and

this indeed will presently emerge — that nitrogen as such does

not play the first and foremost part in the life of plants.

Nevertheless, to understand plant-life it is of the first importance

for us to learn to know the part which nitrogen does play.

Nitrogen, as she

works in the life of Nature, has so to speak four sisters, whose

working we must learn to know at the same time if we would understand

the functions and significance of nitrogen herself in Nature's

so-called household. The four sisters of nitrogen are those that are

united with her in plant and animal protein, in a way that is not yet

clear to the outer science of to-day. I mean the four sisters,

carbon, oxygen, hydrogen and sulphur.

To know the full

significance of protein it will not suffice us to enumerate as its

main ingredients hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and carbon. We must

include another substance, of the profoundest importance for protein,

and that is sulphur. Sulphur in protein is the very element which

acts as mediator between the Spiritual that is spread throughout the

Universe — the formative power of the Spiritual — and the

physical.

Truly we may say,

whoever would trace the tracks which the Spiritual marks out in the

material world, must follow the activity of sulphur. Though this

activity appears less obvious than that of other substances,

nevertheless it is of great importance; for it is along the paths of

sulphur that the Spiritual works into the physical domain of Nature.

Sulphur is actually the carrier of the Spiritual. Hence the ancient

name, “sulphur,” which is closely akin to the name

“phosphorus.” The name is due to the fact that in

olden time they recognised in the out-spreading, sun-filled light,

the Spiritual itself as it spreads far and wide. Therefore they named

“light-bearers” these substances — like sulphur and

phosphorus — which have to do with the working of light into

matter.

Seeing that sulphur's

activity in the economy of Nature is so very fine and delicate, we

shall, however, best approach it by first considering the four other

sisters: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen. These we must first

learn to understand; we shall see what they signify in the whole

being of the Universe. The chemist of to-day knows little of these

substances. He knows what they look like when he has them in his

laboratory, but he knows practically nothing of their inner

significance in the working of the Cosmos as a whole. The knowledge

of modern chemistry about them is scarcely more than our knowledge of

a man of whose outer form we caught a glimpse as we passed by him in

the street — or maybe we took a snapshot of him, and with the

help of the photograph we can now call him to mind. We must learn to

know the deeper essence of these substances. What science does is

scarcely more than to take snapshots of them with a camera. All that

is said of them in scientific books and lectures is scarcely more

than that.

Let us begin with

carbon. (The application of these matters to plant-life will

presently emerge). Carbon indeed has fallen in our time from a highly

aristocratic status to a very plebeian one. Alas, how many other

beings of the Universe have followed it along the same sad way! What

do we see in carbon nowadays? That which we use, as coal, to heat our

ovens! That which we use, as graphite, for our writing. True, we

still assign an aristocratic value to one modification of carbon,

namely diamond, but we have little opportunity to value even that,

for we can no longer afford to buy it!

What is known about

carbon nowadays is very little when you consider its infinite

significance in the Universe. The time is not so very long ago

— only a few centuries — when this black fellow, carbon,

was so highly esteemed as to be called by a very noble name. They

called it the Stone of the Wise — the Philosopher's

Stone. There has been much chatter as to what the “Stone of

the Wise” may be. Very little has emerged from it. When the old

alchemists and such people spoke of the Stone of the Wise, they meant

carbon — in the various modifications in which it occurs. They

held the name so secret and occult, only because if they had not done

so, anyone and everyone would have possessed it — for it was

only carbon. Why then was carbon the “Stone of the

Wise?”

Here we can answer,

with an idea from olden time, a point we need to understand again in

our time when speaking about carbon. It is quite true, carbon occurs

to-day in Nature in a broken, crumbled form, as coal or even graphite

— broken and crumbled, owing to certain processes which it has

undergone. How different it appears, however, when we perceive it in

its living activity, passing through the human or animal body, or

building up the plant-body out of its peculiar conditions. Then the

amorphous, formless substance which we see as coal or carbon proves

to be only the last excrescence — the corpse of that which coal

or carbon truly is in Nature's household.

Carbon, in effect, is

the bearer of all the creatively formative processes in Nature.

Whatever in Nature is formed and shaped be it the form of the plant

persisting for a comparatively short time, or the eternally changing

configuration of the animal body — carbon is everywhere the

great plastician. It does not only carry in itself its black

substantiality. Wherever we find it in full action and inner

mobility, it bears within it the creative and formative cosmic

pictures — the sublime cosmic Imaginations, out of which all

that is formed in Nature must ultimately proceed.

There is a hidden

plastic artist in carbon, and this plastician building the manifold

forms that are built up in Nature — makes use of sulphur in the

process. Truly to see the carbon as it works in Nature, we must

behold the Spirit-activity of the great Universe, moistening itself

so-to-speak with sulphur, and working as a plastic artist —

building with the help of carbon the more firm and well-defined form

of the plant, or again, building the form in man, which passes away

again the very moment it comes into being.

For it is thus that

man is not plant, but man. He has the faculty, time and again to

destroy the form as soon as it arises; for he excretes the carbon,

bound to the oxygen, as carbonic acid. Carbon in the human

body would form us too stiffly and firmly — it would stiffen

our form like a palm. Carbon is constantly about to make us still and

firm in this way, and for this very reason our breathing must

constantly dismantle what the carbon builds. Our breathing tears the

carbon out of its rigidity, unites it with the oxygen and carries it

outward. So we are formed in the mobility which we as human beings

need. In plants, the carbon is present in a very different way. To a

certain degree it is fastened — even in annual plants —

in firm configuration.

There is an old

saying in respect of man: “Blood is a very special fluid”

— and we can truly say: the human Ego, pulsating in the blood,

finds there its physical expression. More accurately speaking,

however, it is in the carbon — weaving and wielding, forming

itself, dissolving the form again. It is on the paths of this carbon

— moistened with sulphur — that that spiritual Being

which we call the Ego of man moves through the blood. And as the

human Ego — the essential Spirit of man — lives in the

carbon, so in a manner of speaking the Ego of the Universe lives as

the Spirit of the Universe — lives via the sulphur in the

carbon as it forms itself and ever again dissolves the form.

In bygone epochs of

Earth-evolution carbon alone was deposited or precipitated. Only at a

later stage was there added to it, for example, the limestone nature

which man makes use of to create something more solid as a basis and

support — a solid scaffolding for his existence. Precisely in

order to enable what is living in the carbon to remain in perpetual

movement, man creates an underlying framework in his limestone-bony

skeleton. So does the animal, at any rate the higher animal. Thus, in

his ever-mobile carbon-formative process, man lifts himself out of

the merely mineral and rigid limestone-formation which the Earth

possesses and which he too incorporates in order to have some solid

Earth within him. For in the limestone form of the skeleton he has

the solid Earth within him.

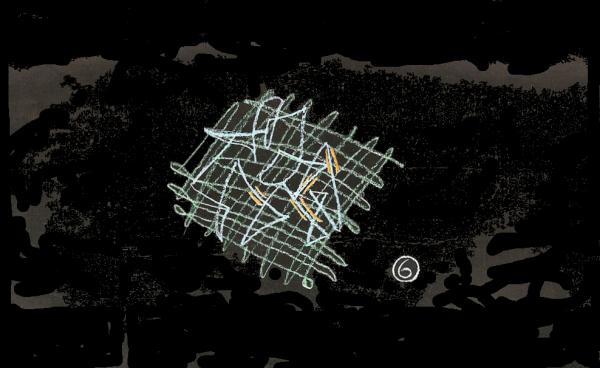

So you can have the

following idea. Underlying all living things is a carbon-like

scaffolding or framework — more or less rigid or fluctuating as

the case may be — and along the paths of this framework the

Spiritual moves through the World. Let me now make a drawing (purely

diagrammatic) so that we have it before us visibly and graphically.

(Diagram 6). I will here draw a scaffolding or

framework such as the Spirit builds, working always with the help of

sulphur. This, therefore, is either the ever-changing carbon

constantly moving in the sulphur, in its very fine dilution —

or, as in plants, it is a carbon-frame-work more or less hard and

fast, having become solidified, mingled with other ingredients.

Now whether it be man

or any other living being, the living being must always be permeated

by an ethereal — for the ethereal is the true bearer of

life, as we have often emphasised. This, therefore, which represents

the carbonaceous framework of a living entity, must in its turn be

permeated by an ethereal. The latter will either stay still —

holding fast to the beams of the framework — or it will also be

involved in more or less fluctuating movement. In either case, the

ethereal must be spread out, wherever the framework is. Once more,

there must be something ethereal wherever the framework is. Now this

ethereal, if it remained alone, could certainly not exist as such

within our physical and earthly world. It would, so to speak, always

slide through into the empty void. It could not hold what it must

take hold of in the physical, earthly world, if it had not a physical

carrier.

This, after all, is

the peculiarity of all that we have on Earth: the Spiritual here must

always have physical carriers. Then the materialists come, and take

only the physical carrier into account, forgetting the Spiritual

which it carries. And they are always in the right — for the

first thing that meets us is the physical carrier. They only leave

out of account that it is the Spiritual which must have a

physical carrier everywhere.

What then is the

physical carrier of that Spiritual which works in the ethereal? (For

we may say, the ethereal represents the lowest kind of spiritual

working). What is the physical carrier which is so permeated by the

ethereal that the ethereal, moistened once more with sulphur, brings

into it what it has to carry — not in Formation this time, not

in the building of the framework — but in eternal quickness and

mobility into the midst of the framework? This physical element which

with the help of sulphur carries the influences of life out of the

universal ether into the physical, is none other than oxygen.

I have sketched it here in green. if you regard it physically, it

represents the oxygen. It is the weaving, vibrant and pulsating

essence that moves along the paths of the oxygen. For the ethereal

moves with the help of sulphur along the paths of oxygen.

Only now does the

breathing process reveal its meaning. In breathing we absorb

the oxygen. A modern materialist will only speak of oxygen such as he

has in his retort when he accomplishes, say, an electrolysis of

water. But in this oxygen the lowest of the super-sensible, that is

the ethereal, is living — unless indeed it has been killed or

driven out, as it must be in the air we have around us. In the air of

our breathing the living quality is killed, is driven out, for the

living oxygen would make us faint Whenever anything more highly

living enters into us we become faint. Even an ordinary hypertrophy

of growth — if it occurs at a place where it ought not to occur

— will make us faint, nay even more than faint. If we were

surrounded by living air in which the living oxygen were present, we

should go about stunned and benumbed. The oxygen around us must be

killed. Nevertheless, by virtue of its native essence it is the

bearer of life — that is, of the ethereal. And it becomes the

bearer of life the moment it escapes from the sphere of those tasks

which are allotted to it inasmuch as it surrounds the human being

outwardly, around the senses. As soon as it enters into us through

our breathing it becomes alive again. Inside us it must be alive.

Circulating inside

us, the oxygen is not the same as it is where it surrounds us

externally. Within us, it is living oxygen, and in like manner it

becomes living oxygen the moment it passes, from the atmosphere we

breathe, into the soil of the Earth. Albeit it is not so highly

living there as it is in us and in the animals, nevertheless, there

too it becomes living oxygen. Oxygen under the earth is not

the same as oxygen above the earth.

It is difficult to

come to an understanding on these matters which the physicists and

chemists, for — by the methods they apply — from the very

outset the oxygen must always be drawn out of the earth realm;

hence they can only have dead oxygen before them. There is no other

possibility for them. That is the fate of every science that only

considers the physical. It can only understand the corpse. In

reality, oxygen is the bearer of the living ether, and the living

ether holds sway in it by using sulphur as its way of access.

But we must now go

farther. I have placed two things side by side; on the one hand the

carbon framework, wherein are manifested the workings of the highest

spiritual essence which is accessible to us on Earth: the human Ego,

or the cosmic spiritual Being which is working in the plants. Observe

the human process: we have the breathing before us — the living

oxygen as it occurs inside the human being, the living oxygen

carrying the ether. And in the background we have the

carbon-framework, which in the human being is in perpetual movement.

These two must come together. The oxygen must somehow find its way

along the paths mapped out by the framework. Wherever any line, or

the like, is drawn by the carbon — by the spirit of the carbon

— whether in man or anywhere in Nature there the ethereal

oxygen-principle must somehow find its way. It must find access to

the spiritual carbon-principle. Flow does it do so? Where is the

mediator in this process?

| |

Figure 3

Click image for large view |

|

The mediator is none

other than nitrogen. Nitrogen guides the life into the

form or configuration which is embodied in the carbon.

Wherever nitrogen occurs, its task is to mediate between the life and

the spiritual essence which to begin with is in the carbon-nature.

Everywhere — in the animal kingdom and in the plant and even in

the Earth — the bridge between carbon and oxygen is built by

nitrogen. And the spirituality which — once again with the help

of sulphur is working thus in nitrogen, is that which we are wont to

describe as the astral. It is the astral spirituality in the

human astral body. It is the astral spirituality in the Earth's

environment. For as you know, there too the astral is working —

in the life of plants and animals, and so on.

Thus, spiritually

speaking we have the astral placed between the oxygen and the carbon,

and this astral impresses itself upon the physical by making use of

nitrogen. Nitrogen enables it to work physically. Wherever nitrogen

is, thither the astral extends. The ethereal principle of life would

flow away everywhere like a cloud, it would take no account of the

carbon-framework were it not for the nitrogen. The nitrogen has an

immense power of attraction for the carbon-framework. Wherever the

lines are traced and the paths mapped out in the carbon, thither the

nitrogen carries the oxygen — thither the astral in the

nitrogen drags the ethereal.

Nitrogen is for ever

dragging the living to the spiritual principle. Therefore, in man,

nitrogen is so essential to the life of the soul. For the soul itself

is the mediator between the Spirit and the mere principle of life.

Truly, this nitrogen is a most wonderful thing. If we could trace its

paths in the human organism, we should perceive in it once more a

complete human being. This “nitrogen-man” actually

exists. If we could peal him out of the body he would be the finest

ghost you could imagine. For the nitrogen-man imitates to perfection

whatever is there in the solid human framework, while on the other

hand it flows perpetually into the element of life.

Now you can see into

the human breathing process. Through it man receives into himself the

oxygen — that is, the ethereal life. Then comes the internal

nitrogen, and carries the oxygen everywhere — wherever there is

carbon, i.e., wherever there is something formed and figured,

albeit in everlasting change and movement. Thither the nitrogen

carries the oxygen, so that it may fetch the carbon and get rid of

it. Nitrogen is the real mediator, for the oxygen to be turned into

carbonic acid and so to be breathed out.

This nitrogen

surrounds us on all hands. As you know, we have around us only a

small proportion of oxygen, which is the bearer of life, and a far

larger proportion of nitrogen—the bearer of the astral spirit.

By day we have great need of the oxygen, and by night too we need

this oxygen in our environment. But we pay far less attention,

whether by day or by night, to the nitrogen. We imagine that we are

less in need of it—I mean now the nitrogen in the air we

breathe. But it is precisely the nitrogen which has a spiritual

relation to us. You might undertake the following experiment.

Put a human being in

a given space filled with air, and then remove a small quantity of

nitrogen from the air that fills the space, thus making the air

around him slightly poorer in nitrogen than it is in normal life. If

the experiment could be done carefully enough, you would convince

yourselves that the nitrogen is immediately replaced. If not from

without, then, as you could prove, it would be replaced from

within the human being. He himself would have to give it off,

in order to bring it back again into that quantitative condition to

which, as nitrogen, it is accustomed. As human beings we must

establish the right percentage-relationship between our whole inner

nature and the nitrogen that surrounds us. It will not do for the

nitrogen around us to be decreased. True, in a certain Sense it would

still suffice us. We do not actually need to breathe nitrogen. But

for the spiritual relation, which is no less a reality, only the

quantity of nitrogen to which we are accustomed in the air is right

and proper. You see from this how strongly nitrogen plays over into

the spiritual realm.

At this point I think

you will have a true idea, of the necessity of nitrogen for the life

of plants. The plant as it stands before us in the soul has only a

physical and an ether-body; unlike the animal, it has not an astral

body within it. Nevertheless, outside it the astral must be there on

all hands. The plant would never blossom if the astral did not touch

it from outside. Though it does not absorb it (as man and the animals

do) nevertheless, the plant must be touched by the astral from

outside. The astral is everywhere, and nitrogen itself — the

bearer of the astral — is everywhere, moving about as a corpse

in the air. But the moment it comes into the Earth, it is alive

again. Just as the oxygen does, so too the nitrogen becomes alive;

nay more it becomes sentient and sensitive inside the Earth. Strange

as it may sound to the materialist madcaps of to-day, nitrogen not

only becomes alive but sensitive inside the Earth; and this is

of the greatest importance for agriculture. Nitrogen becomes the

bearer of that mysterious sensitiveness which is poured out over the

whole life of the Earth.

It is the nitrogen

which senses whether there is the proper quantity of water in a given

district of the Earth. If so, it has a sympathetic feeling. If there

is too little water, it has a feeling of antipathy. It has a

sympathetic feeling if the right plants are there for the given soil.

In a word, nitrogen pours out over all things a kind of sensitive

life. And above all, you will remember what I told you yesterday and

in the previous lectures: how the planets, Saturn, Sun, Moon, etc.,

have an influence on the formation and life of plants. You might say,

nobody knows of that! It is quite true, for ordinary life you can say

so. Nobody knows! But the nitrogen that is everywhere present —

the nitrogen knows very well indeed, and knows it quite correctly.

Nitrogen is not unconscious of that which comes from the Stars and

works itself out in the life of plants, in tim life of Earth.

Nitrogen is the sensitive mediator, even as in our human

nerves-and-senses system it is the nitrogen which mediates for our

sensation. Nitrogen is verily the bearer of sensation. So you

can penetrate into the intimate life of Nature if you can see the

nitrogen everywhere, moving about like flowing, fluctuating feelings.

We shall find the Treatment of nitrogen, above all, infinitely

important for the life of plants. These things we shall enter into

later. Now, however, one thing more is necessary.

You have seen how

there is a living interplay. On the one hand there is that which

works out of the Spirit in the carbon-principle, taking an

forms as of a scaffolding or framework. This is in constant interplay

with what works out of the astral in the nitrogen-principle,

permeating the framework with inner life, making it sentient. And in

all this, life itself is working through the oxygen-principle.

But these things can only work together in the earthly realm inasmuch

as it is permeated by yet another principle, which for our physical

world establishes the connection with the wide spaces of the

Cosmos.

For earthly life it

is impossible that the Earth should wander through the Cosmos as a

solid thing, separate from the surrounding Universe. If the Earth did

so, it would be like a man who lived on a farm but wanted to remain

independent, leaving outside him all is growing in the fields. If he

is sensible, he will not do so! There are many things out in the

fields to-day, which in the near future will be in the stomachs of

this honoured company, and — thence in one way or another

— it will find its way back again on to the fields. As human

beings we cannot truly say that we are separate. We cannot sever

ourselves. We are united with our surroundings — we belong to

our environment. As my little finger belongs to me, so do the things

that are around us naturally belong to the whole human being. There

must be constant interchange of substance, and so it must be between

the Earth — with all its creatures —and the entire

Universe. All that is living in physical forms upon the Earth must

eventually be led back again into the great Universe. It must be able

to be purified and cleansed, so to speak, in the universal All. So

now we have the following:—

To begin with, we

have what I sketched before in blue (Diagram

6), the carbon-framework. Then there is that which you see here

the green—the ethereal, oxygen principle. And then —

everywhere emerging from the oxygen, carried by nitrogen to all these

lines there is that which develops as the astral, as the transition

between the carbonaceous and the oxygen principle. I could show you

everywhere, how the nitrogen carries into these blue lines what is

indicated diagrammatically in the green.

But now, all that is

thus developed in the living creature, structurally as in a fine and

delicate design, must eventually be able to vanish again. It is not

the Spirit that vanishes, but that which the Spirit has built into

the carbon, drawing the life to itself out of the oxygen as it does

so. This must be able once more to disappear. Not only in the sense

that it vanishes on Earth; it must be able to vanish into the

Cosmos, into the universal All.

This is achieved by a

substance which is as nearly as possible akin to the physical and yet

again as nearly akin to the spiritualand that is hydrogen.

Truly, in hydrogen — although it is itself the finest of

physical elements — the physical flows outward, utterly broken

and scattered, and carried once more by the sulphur out into the

void, into the indistinguishable realms of the Cosmos.

We may describe the

process thus: In all these structures, the Spiritual has become

physical. There it is living in the body astrally, there it is living

in its image, as the Spirit or the Ego — living in a physical

way as Spirit transmuted into the physical. After a time, however, it

no longer feels comfortable there. It wants to dissolve again. And

now once more — moistening itself with sulphur — it needs

a substance wherein it can take its leave of all structure and

definition, and find its way outward into the undefined chaos of the

universal All, where there is nothing more of this organisation or

that.

Now the substance

which is so near to the Spiritual on the one hand and to the

substantial on the other, is hydrogen. Hydrogen carries out again

into the far spaces of the Universe all that is formed, and

alive, and astral. Hydrogen carries it upward and

outward, till it becomes of such a nature that it can be received out

of the Universe once more, as we described above. It is hydrogen

which dissolves everything away.

So then we have these

five substances. They, to begin with, represent what works and weaves

in the living — and in the apparently dead, which after all is

only transiently dead. Sulphur, carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen:

each of these materials is inwardly related to a specific spiritual

principle. They are therefore very different from what our modern

chemists would relate. Our chemists speak only of the corpses of the

substances — not of the real substances, which we must rather

learn to know as sentient and living entities, with the single

exception of hydrogen. Precisely because hydrogen is apparently the

thinnest element — with the least atomic weight —it is

really the least spiritual of all.

And now I ask you to

observe: When you meditate, what are you really doing? (I must insert

this observation; I want you to see that these things are not

conceived “out of the blue”). The Orientals used to

meditate in their way; we in the mid-European West do it in our way.

Our meditation is connected only indirectly with the

breathing. We live and weave in concentration and meditation.

However, all that we do when we devote ourselves to these exercises

of the soul still has its bodily counterpart. Albeit this is delicate

and subtle, nevertheless, however subtly, meditation somewhat

modifies the regular course of our breathing, which as you know is

connected so intimately with the life of man.

In meditating, we

always retain in ourselves a little more carbon dioxide than we do in

the normal process of waking consciousness. A little more carbon

dioxide always remains behind in us. Thus we do not at once expel the

full impetus of the carbonic acid, as we do in the everyday,

bull-at-the-gate kind of life. We keep a little of it back. We do not

drive the carbon dioxide with its full momentum out into the

surrounding spaces, where the nitrogen is all around us. We keep it

back a little.

If you knock up

against something with your skull — if you knock against a

table, for example — you will only be conscious of your own

pain. If, however, you rub against it gently, you will be conscious

of the surface of the table. So it is when you meditate. By and by

you grow into a conscious living experience of the nitrogen all

around you. Such is the real process in meditation. All becomes

knowledge and perception —even that which is living in the

nitrogen. And this nitrogen is a very clever fellow! He will inform

you of what Mercury and Venus and the rest are doing. He knows it

all, he really senses it. These things are based on absolutely real

processes, and I shall presently touch on some of them in somewhat

greater detail. This is the point where the Spiritual in our inner

life bearing to have a certain bearing on our work as farmers.

This is the point

which has always awakened the keen interest of our dear friend

Stegemann. I mean this working-together of the soul and Spirit in us,

with all that is around us. It is not at all a bad thing if he who

has farming to do can meditate. He thereby makes himself receptive to

the revelations of nitrogen. He becomes more and more receptive to

them. If we have made ourselves thus receptive to nitrogen's

revelations, we shall presently conduct our farming in a very

different style than before. We suddenly begin to know all kinds of

things, all kinds of things emerge. All kinds of secrets that prevail

in farm and farmyard — we suddenly begin to know them.

Nay more! I cannot

repeat what I said here an hour ago, but in another way I may perhaps

characterise it again. Think of a simple peasant-farmer, one whom

your scholar will certainly not deem to be a learned man. There he

is, walking out over his fields. The peasant is stupid —so the

learned man will say. But in reality it is not true, for the simple

reason that the peasant —forgive me, but it is so — is

himself a meditator. Oh, it is very much that he meditates in

the long winter nights! He does indeed acquire a kind of method

— a method of spiritual perception. Only he cannot express it.

It suddenly emerges in him. We go through the fields, and all of a

sudden the knowledge is there in us. We know it absolutely.

Afterwards we put it to the test and find it confirmed. I in my

youth, at least, when I lived among the peasant folk, could witness

this again and again. It really is so, and from such things as these

we must take our start once more. The merely intellectual life is not

sufficient — it can never lead into these depths. We must begin

again from such things. After all, the weaving life of Nature is very

fine and delicate. We cannot sense it — it eludes our

coarse-grained intellectual conceptions. Such is the mistake science

has made in recent times. With coarse-grained, wide-meshed

intellectual conceptions it tries to apprehend things that are far

more finely woven.

All of these

substances — sulphur, carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen — all

are united together in protein. Now we are in a position to

understand the process of seed-formation a little more fully than

hitherto. Wherever carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen occur — in leaf

or flower, calyx or root — everywhere they are bound to other

substances in one form or another. They are dependent on these other

substances; they are not independent. There are only two ways in

which they can become independent: namely, on the one hand when the

hydrogen carries them outward into the far spaces of the Universe

— separates them all, carries them all away and merges them

into an universal chaos; and on the other hand, when the hydrogen

drives these fundamental substances of protein into the tiny

seed-formation and makes them independent there, so that they become

receptive to the inpouring forces of the Cosmos. In the tiny

seed-formation there is chaos, and away in the far circumference

there is chaos once more. Chaos in the seed must interact with chaos

in the farthest circles of the Universe. Then the new being

arises.

Now let us look how

the action of these so-called substances — which in reality are

bearers of the Spirit — comes about in Nature. You see, that

which works even inside the human being as oxygen and nitrogen,

behaves itself tolerably well. There in the human being the

properties of oxygen and nitrogen are living. One only does not

perceive them with ordinary science, for they are hidden to outward

appearance. But the products of the carbon and hydrogen principles

cannot behave quite so simply.

Take, to begin with,

carbon. When the carbon, with its inherent activity, comes from the

plant into the animal or human kingdom, it must first become mobile

— in the transient stage at any rate. If it is then to present

the firm and solid figure (man or animal), it must build on a more

deep-seated scaffolding or framework. This is none other than the

very deep-seated framework which is contained, not only in our bony

skeleton with its limestone — nature, but also in the

silicious element which we continually bear within us.

To a certain extent,

the carbon in man and animal masks its native power of configuration.

It finds a pillar of support in the configurative forces of limestone

and silicon. Limestone gives it the earthly, silicon the cosmic

formative power. Carbon, therefore, in man himself — and in the

animal — does not declare itself exclusively competent, but

seeks support in the formative activities of limestone and

silicon.

Now we find limestone

and silicon as the basis of plant growth too. Our need is to gain a

knowledge of what the carbon develops throughout the process of

digestion, breathing and circulation in man — in relation to

the bony structure and the silicious structure. We must somehow

evolve a knowledge of what is going on in there — inside the

human being. We should be able to see it all, if we could somehow

creep inside. We should see the carbonaceous formative activity

raying out from the circulatory process into the calcium and silicon

in man.

This is the kind of

vision we must unfold when we look out over he surface of the Earth,

covered as it is with plants and having beneath it the limestone and

the silica — the calcium and silicon. We cannot look inside the

human being; we must evolve the same knowledge by looking out over

the Earth. There we behold the oxygen-nature caught up by the

nitrogen and carried down into the carbon-nature. (The carbon itself,

however, seeks support in the principles of calcium and silicon. We

might also say, the process only passes through the carbon).

That which is living in our environment — kindled to life in

the oxygen — must be carried into the depths of the Earth,

there to find support in the silica, working formatively in the

calcium or limestone.

If we have any

feeling or receptivity for these things, we can observe the process

most wonderfully in the papilionaceae or leguminosae

— in all those plants which are well known in farming as the

nitrogen-collectors. They indeed have the function of drawing in the

nitrogen, so to communicate it to that which is beneath them. Observe

these leguminosae. We may truly say, down there in the Earth

something is athirst for nitrogen; something is there that needs it,

even as the lung of man needs oxygen. It is the limestone principle.

Truly we may say, the limestone in the Earth is dependent on a kind

of nitrogen-inbreathing, even as the human lung depends on the

inbreathing of oxygen. These plants — the papilionaceae —

represent something not unlike what takes place on our epithelial

cells. By a kind of inbreathing process it finds its way down there.

Broadly speaking, the

papilionaceae are the only plants of this kind. All other plants are

akin, not to the inbreathing, but to the outbreathing process.

Indeed, the entire organism of the plant-world is dissolved into two

when we contemplate it in relation to nitrogen. Observe it as a kind

of nitrogen-breathing, and the entire organism of the plant-world is

thus dissolved. On the one hand, where we encounter any species of

papilionaceae, we are observing as it were the paths of the

breathing, and where we find any other plants, there we are looking

at the remaining organs, which breathe in a far more hidden way and

have indeed other specific functions. We must learn to regard the

plant-world in this way. Every plant species must appear to us,

placed in the total organism of the plant-world, like the single

human organs in the total organism of man. We must regard the several

plants as parts of a totality. Look on the matter in this way, and we

shall perceive the great significance of the papilionaceae. It is no

doubt already known, but we must also recognise the spiritual

foundations of these things. Otherwise the danger is very great that

in the near future, when still more of the old will be lost, men will

adopt false paths in the application of the new.

Observe how the

papilionaceae work. They all have the tendency to retain, to some

extent in the region of the leaf-like nature, the fruiting

process which in the other plants goes farther upward. They have a

tendency to fruit even before the flowering process. You can see this

everywhere in the papilionaceae; they tend to fruit even before they

come to flower. It is due to the fact that they retain far nearer to

the Earth that which expresses itself in the nitrogen nature. Indeed,

as you know, they actually carry the nitrogen-nature into the

soil.

Therefore, in these

plants, everything that belongs to nitrogen lives far more nearly

inclined to the Earth than in the other plants, where it evolves at a

greater distance from the Earth. See how they tend to colour their

leaves, not with the ordinary green, but often with a darker shade.

Observe too how the fruit, properly speaking, tends to be stunted.

The seeds, for instance, only retain their germinating power for a

short time, after which they lose it.

In effect, these

plants are so organised as to bring to expression, most of all, what

the plant-world receives from the winter — not what it has from

the summer. Hence, one would say, there is always a tendency in these

plants to wait for the winter. With all that they evolve, they tend

to wait for the winter. Their growth is retarded when they find a

sufficiency of what they need — i.e., of the nitrogen of

the air, which in their own way they can carry downward.

In such ways as these

we can look into the life and growth of all that goes on in and above

the surface of the soil. Now you must also include this fact: the

limestone-nature has in it a wonderful kinship to the world of human

cravings. See how it all becomes organic and alive! Take the chalk or

limestone when it is still in the form of its element — as

calcium. Then indeed it gives no rest at all. It wants to feel and

fill itself at all costs; it wants to become quicklime that is, to

unite its calcium with oxygen. Even then it is not satisfied, but

craves for all sorts of things — wants to absorb all manner of

metallic acids, or even bitumen which is scarcely mineral at all. It

wants to draw everything to itself. Down there in the ground it

unfolds a regular craving-nature.

He who is sensitive

will feel this difference, as against a certain other substance.

Limestone sucks us out. We have the distinct feeling: wherever the

limestone principle extends, there is something that reveals a

thorough craving nature. It draws the very plant-life to itself. In

effect, all that the limestone desires to have, lives in the

plant-nature. Time and again, this must be wrested away from it. How

so? By the most aristocratic principle — that which desires

nothing for itself. There is such a principle, which wants for

nothing more but rests content in itself. That is the

silica-nature. It has indeed come to rest in itself.

If men believe that

they can only see the silica where it has hard mineral outline, they

are mistaken. In homeopathic proportions, the silicious principle is

everywhere around us;.moreover it rests in itself — it makes no

claims. Limestone claims everything; the silicon principle claims

nothing for itself. It is like our own sense organs. They too do not

perceive themselves, but that which is outside them. The

silica-nature is the universal sense within the earthly realm,

the limestone-nature is the universal craving; and the clay

mediates between the two. Clay stands rather nearer to the silicious

nature, but it still mediates towards the limestone.

These things we ought

at length to see quite clearly; then we shall gain a kind of

sensitive cognition. Once more we ought to feel the chalk or

limestone as the kernel-of-desire. Limestone is the fellow who would

like to snatch at everything for himself. Silica, on the other hand,

we should feel as the very superior gentleman who wrests away all

that can be wrested from the clutches of the limestone, carries it

into the atmosphere, and so unfolds the forms of plants. This

aristocratic gentleman, silica, lives either in the ramparts of his

castle — as in the equisetum plant — or else distributed

in very fine degree, sometimes indeed in highly homeopathic doses.

And he contrives to tear away what must be torn away from the

limestone.

Here once more you

see how we encounter Nature's most wonderfully intimate workings.

Carbon is the true form-creator in all plants; carbon it is that

forms the framework or scaffolding. But in the course of earthly

evolution this was made difficult for carbon. It could indeed

form the plants if it only had water beneath it. Then it would be

equal to the task. But now the limestone is there beneath it, and the

limestone disturbs it. Therefore it allies itself to silica. Silica

and carbon together — in union with clay, once more create the

forms. They do so in alliance because the resistance, of the

limestone-nature must be overcome.

How then does the

plant itself live in the midst of this process? Down there below, the

limestone-principle tries to get hold of it with tentacles and

clutches, while up above the silica would tend to make it very fine,

slender and fibrous — like the aquatic plants. But in the midst

— giving rise to our actual plant forms — there is the

carbon, which orders all these things. And as our astral body

brings about an inner order between our Ego and our ether

body, so does the nitrogen work in between, as the astral.

All this we must

learn to understand. We must perceive how the nitrogen is there at

work, in between the lime — the clay — and the silicious

— natures —in between all that the limestone of itself

would constantly drag downward, and the silica of itself would

constantly ray upward. Here then the question arises, what is the

proper way to bring the nitrogen-nature into the world of plants? We

shall deal with this question tomorrow, and so find our way to the

various forms of manuring.

|