|

LECTURE

V

If

you recall that in the course of our lectures we have come to look

upon the Christ-Impulse as the most profound event in human

evolution, you will doubtless agree that some exertion of our powers

of mind and spirit is needed to understand its full meaning and range

of influence. Certainly in the widest circles we find the bad habit

of saying that the highest things in the world must be comprehensible

in the simplest terms. If what someone is constrained to say about

the sources of existence appears complicated, people turn away from

it because ‘the truth must be simple’. In the last resort

it certainly is simple. But if at a certain stage we wish to learn to

know the highest things, it is not hard to see that we must first

clear the way to understanding them. And in order to enter into the

full greatness, the full significance, of the Christ-Impulse, from a

particular point of view, we must bring together many different

matters.

We need only turn to the Pauline Epistles and we shall

soon see that Paul, who sought especially to bring within range of

human minds the super-sensible nature of the Christ-Being, has drawn

into the concept, the idea, of the Christ, the whole of human

evolution, so to speak. If we let the Pauline Epistles work upon us,

we have finally something which, through its extraordinary simplicity

and through the deeply penetrating quality of the words and

sentences, makes a most significant impression. But this is so only

because Paul, through his own initiation, had worked his way up to

that simplicity which is not the starting-point of what is true, but

the consequence, the goal. If we wish to penetrate into what Paul was

able finally to express in wonderful, monumental, simple words

concerning the Christ-Being, we must come nearer to an understanding

of human nature, for whose further development on Earth the

Christ-Impulse came. Let us therefore consider what we already know

concerning human nature, as shown through occult sight.

We divide the life

of Man into two parts: the period between birth and death, and the

period which runs its course between death and a new birth. Let us

first of all look at man in his physical body. We know that occult

sight sees him as a four-fold being, but as a four-fold being in

process of development. Occult sight sees the physical body, etheric

body, astral body and the Ego. We know that in order to understand

human evolution we must learn the occult truth that this Ego, of

which we become aware in our feelings and perceptions when we simply

look away from the external world and try to live within ourselves,

goes on from incarnation to incarnation. But we also know that this

Ego is, as it were, ensheathed — although ‘ensheathed’

is not a good expression, we can use it for the present — by

three other members of human nature, the astral body, the etheric

body and the physical body. Of the astral body we know that in a

certain respect it is the companion of the Ego through the various

incarnations. For though during the Kamaloka time much of the astral

body must be shed, it remains as a kind of force-body, which holds

together the moral, intellectual and aesthetic progress we have

stored up during an incarnation. Whatever constitutes true progress

is held together by the power of the astral body, is carried from one

incarnation to another, and is linked, as it were, with the Ego,

which passes as the fundamentally eternal in us from incarnation to

incarnation. Further, we know that from the etheric body, too, very

much is cast off immediately after death, but an extract of this

etheric body remains with us, an extract we take with us from one

incarnation to another. In the first days directly after death we

have before us a kind of backward review, like a great tableau, of

our life up to that time, and we take with us a concentrated etheric

extract. The rest of the etheric body is given over into the general

etheric world in one form or another, according to the development of

the person concerned.

When, however, we

look at the fourth member of the human being, the physical body, it

seems at first as if the physical body simply disappears into the

physical world. One might say that this can be externally

demonstrated, for to external sight the physical body is brought in

one way or another to dissolution. The question, however, which

everyone who occupies himself with Spiritual Science must put to

himself is the following. Is not all that external physical cognition

can tell us about the fate of our physical body perhaps only Maya?

The answer does not lie very far away for anyone who has begun to

understand Spiritual Science. When a man can say to himself, ‘All

that is offered by sense-appearance is Maya, external illusion’,

how can he think it really true that the physical body, delivered

over to the grave or to the fire, disappears without trace, however

crudely the appearance may obtrude on his senses? Perhaps, behind the

external Maya, there lies something much deeper. Let us go further

into this.

You will realise

that in order to understand the evolution of the Earth, we must know

the earlier embodiments of our planet; we must study the Saturn, Sun,

and Moon embodiments of the Earth. We know that the Earth has gone

through its ‘incarnations’ just as every human being has

done. Our physical body was prepared in the course of human evolution

from the Saturn period of the Earth. With regard to the ancient

Saturn time we cannot speak at all of etheric body, astral body, and

Ego in the sense of the present day. But the germ for the physical

body was already sown, was embodied, during the Saturn evolution.

During the Sun period of the Earth this germ was transformed, and

then in this germ, in its altered form, the etheric was embodied.

During the Moon period of the Earth the physical body was again

transformed, and in it, and at the same time in the etheric body,

which also came forth in an altered form, the astral body was

incorporated. During the Earth period the Ego was incorporated. And

is it conceivable that the part of us which was embodied during the

Saturn period, our physical body, simply decomposes or is burned up

and disappears into the elements, after the most significant

endeavours had been made by divine-spiritual Beings through millions

and millions of years, during the Saturn, Sun and Moon periods, in

order to produce this physical body? If this were true, we should

have before us the very remarkable fact that through three planetary

stages, Saturn, Sun, Moon, a whole host of divine Beings worked to

produce a cosmic element, such as our physical body is, and that

during the Earth period this cosmic element is destined to vanish

every time a person dies. It would be a remarkable drama if Maya —

and external observation knows nothing else — were right. So

now we ask: Can Maya be right?

At first it certainly seems as though occult knowledge

declares Maya to be correct, for, strangely enough, occult knowledge

seems in this case to harmonise with Maya. When we study the

description given by spiritual knowledge of the development of man

after death, we find that scarcely any notice is taken of the

physical body. We are told that the physical body is thrown off, is

given over to the elements of the Earth. We are told about the

etheric body, the astral body, the Ego. The physical body is not

further touched upon, and it seems as though the silence of spiritual

knowledge were giving tacit assent to Maya-knowledge. So it seems,

and in a certain way we are justified by Spiritual Science in

speaking thus, for everything further must be left to a deeper

grounding in Christology. For concerning what goes beyond Maya with

regard to the physical body we cannot speak at all correctly unless

the Christ-Impulse and everything connected with it has first been

sufficiently explained.

If we observe how this physical body was experienced at

some definite moment in the past, we shall reach a quite remarkable

result. Let us enquire into three kinds of folk-consciousness, three

different forms of human consciousness concerning all that is

connected with our physical body, during decisive periods in human

evolution. We will enquire first of all among the Greeks.

We know that the

Greeks were that remarkable people who rose to their highest

development in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch of civilisation. We

know that this epoch began about the eighth century before our era,

and ended in the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries

after the Event of Palestine. We can easily confirm what is said

about this period from external information, traditions, and

documents. The first dimly clear accounts concerning Greece hardly go

back farther than the sixth or seventh century before our era, though

legendary accounts come down from still earlier times. We know that

the greatness of the historical period of Greece has its source in

the preceding period, the third post-Atlantean epoch. The inspired

utterances of Homer reach back into the period preceding the fourth

post-Atlantean epoch; and Aeschylus, who lived so early that a number

of his works have been lost, points back to the drama of the

Mysteries, of which he offers us but an echo. The third

post-Atlantean epoch extends into the Greek age, but in that age the

fourth epoch comes to full expression. The wonderful Greek culture is

the purest expression of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch.

Now there falls upon

our ear a remarkable saying from this land of Greece, a saying which

permits us to see deeply into the soul of the man who felt himself

truly a Greek, the saying of the hero (Achilles, in the Odyssey):

‘Better a beggar in the upper world, than a king in the land of

shades.’ Here is a saying which betrays the deep susceptibility

of the Greek soul. One might say that everything preserved to us of

Greek classical beauty and classical greatness, of the gradual

formation of the human ideal in the external world — all this

resounds to us from that saying.

Let us recall the

wonderful training of the human body in Greek gymnastics and in the

great Games, which are only caricatured in these days by persons who

understand nothing of what Greece really was. Every period has its

own ideal, and we must keep this in mind if we want to understand how

this development of the external physical body, as it stands there in

its own form on the physical plane, was a peculiar privilege of the

Greek spirit. So, too, was the creation of human ideals in plastic

art, the enhancement of the human form in sculpture. And if we then

look at the character of the Greek consciousness, as it held sway in

a Pericles, for example, when a man had a feeling for the universally

human and yet could stand firmly on his own feet and feel like a lord

and king in the domain of his city — when we let all this work

upon us, then we must say that the real love of the Greek was for the

human form as it stood there before him on the physical plane, and

that aesthetics, too, were turned to account in the development of

this form. Where this human form was so well loved and understood,

one could give oneself up to the thought: ‘When that which

gives to man this beautiful form on the physical plane is taken away

from human nature, one cannot value the remainder as highly as the

part destroyed by death.’ This supreme love for the external

form led unavoidably to a pessimistic view of what remains of man

when he has passed through the gate of death. And we can fully

understand that the Greek soul, having looked with so great a love

upon the outer form, felt sad when compelled to think: ‘This

form is taken away from the human individuality. The human

individuality lives on without this form!’ If for the moment

one looks at it solely from the point of view of feeling, then we

must say: We have in Greece that branch of the human race which most

loved and valued the human body, and underwent the deepest sorrow

when the body perished in death. Now let us consider another

consciousness which developed about the same time, the Buddha

consciousness, which had passed over from Buddha to his followers.

There we have almost the opposite of the Greek attitude. We need only

remember one thing: the kernel of the four great truths of Buddha is

that human individuality is drawn by longing, by desire, into the

existence where it is enshrouded by an external form. Into what kind

of existence? Into an existence described in the Buddha-teaching as

‘Birth is sorrow, sickness is sorrow, old age is sorrow, death

is sorrow!’ The underlying thought in this kernel of Buddhism

is that by being enshrouded in an external bodily sheath, our

individuality, which at birth comes down from divine-spiritual

heights and returns to divine-spiritual heights at death, is exposed

to the pain of existence, to the sorrow of existence. Only one way of

salvation for men is expressed in the four great holy truths of

Buddha: to become free from external existence, to throw off the

external sheath. This means transforming the individuality so that it

comes as soon as possible into a condition which will permit this

throwing off. We note that the active feeling here is the reverse of

the feeling dominant among the Greeks. Just as strongly as the Greek

loved and valued the external bodily sheath, and felt the sadness of

casting it aside, just as little did the adherent of Buddhism value

it, regarding it as something to be cast aside as quickly as

possible. And linked with this attitude was the struggle to overcome

the craving for existence, an existence enshrouded by a bodily

sheath.

Let us go a little

more deeply into these Buddhist thoughts. A kind of theoretical view

meets us in Buddhism concerning the successive incarnations of man.

It is not so much a question of what the individual thinks about the

theory, as of what has penetrated into the consciousness of the

adherents of Buddhism. I have often described this. I have said that

we have perhaps no better opportunity of feeling what an adherent of

Buddhism must have felt in regard to the continual incarnations of

man, than by immersing ourselves in the traditional conversation

between King Milinda and a Buddhist sage. ‘Thou hast come in

thy carriage: then reflect, O great King,’ said the sage

Nagasena, ‘that all thou hast in the carriage is nothing but

the wheels, the shaft, the body of the carriage and the seat, and

beyond these nothing else exists except a word which covers wheels,

shaft, body of carriage, seat, and so on. Thus thou canst not speak

of a special individuality of the carriage, but thou must clearly

understand that “carriage” is an empty word if thou

thinkest of anything else than its parts, its members.’ And

another simile was chosen by Nagasena for King Milinda. ‘Consider

the almond-fruit which grows on the tree, and reflect that out of

another fruit a seed was taken and laid in the earth and has decayed;

out of that seed the tree has grown, and the almond-fruit upon it.

Canst thou say that the fruit on the tree has anything else in common

other than name and external form with the fruit from which the seed

was taken and laid in the earth, where it decayed?’ A man,

Nagasena meant to say, has just as much in common with the man of his

preceding incarnation as the almond-fruit on the tree has with the

almond-fruit which, as seed, was laid in the earth. Anyone who

believes that the form which stands before us as man, and is wafted

away by death, is anything else than name and form, believes

something as false as he who thinks that in the carriage — in

the name ‘carriage’ — something else is contained

than the parts of the carriage — the wheels, shaft, and so on.

From the preceding incarnation nothing of what man calls his Ego

passes over into the new incarnation.

That is important!

And we must repeatedly emphasise that it is not to the point how this

or that person chooses to interpret this or that saying of the

Buddha, but how Buddhism worked in the consciousness of the people,

what it gave to their souls. And what it gave to their souls is

indeed expressed with intense clearness and significance in this

parable of King Milinda and the Buddhist sage. Of what we call the

‘Ego’, and of which we say that it is first felt and

perceived by man when he reflects upon his inner being, the Buddhist

says that fundamentally it is something that flows into him, and

belongs to Maya as much as everything else that does not go from

incarnation to incarnation.

I have elsewhere

mentioned that if a Christian sage were to be compared with the

Buddhist one, he would have spoken differently to King Milinda. The

Buddhist said to the King: ‘Consider the carriage, wheels,

shaft, and so on; they are parts of the carriage, and beyond these

parts carriage is only a name and form. With the word carriage thou

hast named nothing real in the carriage. If thou wilt speak of what

is real, thou must name the parts.’ In the same case the

Christian sage would have said: ‘O wise King Milinda, thou hast

come in thy carriage; look at it! In it thou canst see only the

wheels, the shaft, the body of the carriage and so on, but I ask thee

now: Canst thou travel hither with the wheels only? Or with the shaft

only, or with the seat only? Thou canst not travel hither on any of

the separate parts. So far as they are parts they make the carriage,

but on the parts thou canst not come hither. In order that the

assembled parts can make the carriage, something else is necessary

than their being merely parts. There must first be the quite definite

thought of the carriage, for it is this that brings together wheels,

shaft, and so on. And the thought of the carriage is something very

necessary: thou canst indeed not see the thought, but thou must

recognise it!’

The Christian sage

would then turn to man and say: ‘Of the individual person thou

canst see only the external body, the external acts, and the external

soul-experiences; thou seest in man just as little of his Ego as in

the name carriage thou seest its separate parts. Something quite

different is established within the parts, namely that which enables

thee to travel hither. So also in man: within all his parts something

quite different is established, namely that which constitutes the

Ego. The Ego is something real which as a super-sensible entity goes

from one incarnation to another.’

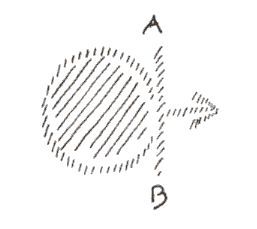

How can we make a

diagram of the Buddhist teaching of reincarnation, so that it will

represent the corresponding Buddhist theory? With the circle we

indicate a man between birth and death. The man dies. The time when

he dies is marked by the point where the circle touches the line A–B.

Now what remains of all that has been spellbound within his existence

between birth and death? A summation of causes: the results of acts,

of everything a man has

| |

Diagram 3

Click image for large view | |

done,

good or bad, beautiful or ugly, clever or stupid. All that remains

over in this way works on as a set of causes, and so forms the causal

nucleus (C) for the next incarnation. Round this causal nucleus new

body-sheaths (D) are woven for the next incarnation. These

body-sheaths go through new experiences, as did the body-sheaths

around the earlier causal nucleus. From these experiences there

remains again a causal nucleus (E). It includes experiences that have

come into it from earlier incarnations, together with experiences

from its last life. Hence it serves as the causal nucleus for the

next incarnation, and so on. This means that what goes through the

incarnations consists of nothing but causes and effects. There is no

continuing Ego to connect the incarnations; nothing but causes and

effects working over from one incarnation into the next. So when in

this incarnation I call myself an ‘Ego’, this is not

because the same Ego was there in the preceding incarnation. What I

call my Ego is only a Maya of the present incarnation.

Anyone who really knows Buddhism must picture it in this

way, and he must clearly understand that what we call the Ego has no

place in Buddhism. Now let us go on to what we know through

anthroposophical cognition.

How has man ever been able to develop his Ego? Through

the Earth-evolution. Only in the course of the Earth-evolution has he

reached the stage of developing his Ego. It was added to his physical

body, etheric body and astral body on the Earth. Now, if we remember

all we had to say concerning the evolutionary phases of man during

the Saturn, Sun and Moon periods, we know that during the Moon period

the human physical body had not yet acquired a quite definite form;

it received this first on Earth. Hence we speak of the

Earth-existence as the epoch in which the Spirits of Form first took

part, and metamorphosed the physical body of man so that it has its

present form. This forming of the human physical body was necessary

if the Ego were to find a place in man. The physical Earth-body, set

down on the physical Earth, provided the foundation for the dawn of

the Ego as we know it. If we keep this in mind, what follows will no

longer seem incomprehensible.

With regard to the valuation of the Ego among the Greeks, we saw that for

them it was expressed externally in the human form. Let us now recall

that Buddhism, according to its knowledge, sets out to overcome and

cast off as quickly as possible the external form of the human

physical body. Can we then wonder that in Buddhism we find no value

attached to anything connected with this bodily form? It is the

essence of Buddhism to value the external form of the physical body

as little as it values the external form which the Ego needs in order

to come into being: indeed, all this is completely set aside.

Buddhism lost the form of the Ego through the way in which it

undervalued the physical body.

| |

Diagram 4

Click image for large view | |

Thus we see how these two spiritual currents are

polarically opposed: the Greek current, which set the highest value

on the external form of the physical body as the external form of the

Ego, and Buddhism, which requires that the external form of the

physical body, with all craving after existence, shall be overcome as

soon as possible, so that in its theory it has completely lost the

Ego.

Between these two opposite world-philosophies stands

ancient Hebraism. Ancient Hebraism is far from thinking so poorly of

the Ego as Buddhism does. In Buddhism, it is heresy to recognise a

continuous Ego, going on from one incarnation to the next. But

ancient Hebraism held very strongly to this so called heresy, and it

would never have entered the mind of an adherent of that religion to

suppose that his personal divine spark, with which he connected his

concept of the Ego, is lost when he goes through the gate of death.

If we want to make clear how the ancient Hebrew regarded the matter,

we must say that he felt himself connected in his inner being with

the Godhead, intimately connected; he knew that through the finest

threads of his soul-life, as it were, he was dependent on the being

of this Godhead.

With regard to the

concept of the Ego, the ancient Hebrew was quite different from the

Buddhist, but in another respect he was also very different from the

Greek. When we survey those ancient times as a whole, we find that

the estimation of human personality, and hence that valuation of the

external human form which was peculiar to the Greek, is not present

in ancient Hebraism. For the Greek it would have been absolute

nonsense to say: ‘Thou shalt not make to thyself any image of

thy God.’ He would not have understood if someone had said to

him: ‘Thou shalt not make to thyself any image of thy Zeus, or

thy Apollo.’ For he felt that the highest thing was the

external form, and that the highest tribute a man could offer to the

Gods was to clothe them with this human form which he himself valued

so much. Nothing would have seemed more absurd to him than the

commandment: ‘Thou shalt make to thyself no image of God.’

As artist, the Greek gave his human form to his gods. He thought of

himself as made in the likeness of the Divine, and he carried out his

contests, his wrestling, his gymnastics and so on, in order to become

a real copy of the God.

But the ancient

Hebrew had the commandment, ‘Thou shalt make to thyself no

image of God!’ This was because he did not value the external

form as the Greeks had done; he regarded it as unworthy in relation

to the Divine. The ancient Hebrew was as far removed on the one side

from the disciple of Buddhism, who would have much preferred to cast

off the human form entirely on passing through death, as he was on

the other side from the Greek. He was mindful of the fact that it was

this form that gave expression to the commands, the laws, of the

Divine Being, and he clearly understood that a ‘righteous man’

handed down through the following generations what he, as a righteous

man, had gathered together. Not the extinguishing of the form, but

the handing on of the form through the generations was what concerned

the ancient Hebrew. His point of view stood midway between that of

the Buddhist, who had lost the value of the Ego, and that of the

Greek, who saw in the form of the body the very highest, and felt it

as sorrowful when the bodily form had to disappear with death.

So these three views

stand over against one another. And for a closer understanding of

ancient Hebraism we must make it clear that what the Hebrew valued as

his Ego was in a certain sense also the Divine Ego. The God lived on

in humanity, lived within man. In his union with the God, the Hebrew

felt at the same time his own Ego, and felt it to be coincident with

the Divine Ego. The Divine Ego sustained him; the Divine Ego was

active within him. The Greek said: ‘I value my Ego so greatly

that I look with horror on what will happen to it after death.’

The Buddhist said: ‘That which is the cause of the external

form of man must fall away from man as soon as possible.’ The

Hebrew said: ‘I am united with God; that is my fate, and as

long as I am united with Him I bear my fate. I know nothing else than

the identification of my Ego with the Divine Ego.’

This old Judaic mode

of thought, standing midway between Greek thought and Buddhism, does

not involve, as Greek thought does from the outset, a predisposition

to tragedy in face of the phenomenon of death, but tragic feeling is

indirectly present in it. It is truly Greek for the hero to say:

‘Better a beggar in the upper world’ — i.e. with

the human bodily form — ‘than a king in the realm of

shades’, but a Hebrew could not have said it without something

more. For the Hebrew knows that when in death his bodily form falls

away, he remains united with God. He cannot fall into a tragic mood

simply through the fact of death. Still, the predisposition to

tragedy is present indirectly in ancient Hebraism, and is expressed

in the most wonderfully dramatic story ever written in ancient times,

the story of Job.

We see there how the Ego of Job feels bound up with his

God, how it comes into conflict with his God, but differently from

the way in which the Greek Ego comes into conflict. We are shown how

misfortune after misfortune falls upon Job, although he is conscious

that he is a righteous man and has done all he can to maintain the

connection of his Ego with the Divine Ego. And while it seems that

his existence is blessed and ought to be blessed, a tragic fate

breaks over him.

Job is not aware of

any sin; he is conscious that he has acted as a righteous man must

act towards his God. Word is brought to him that all his possessions

have been destroyed, all his family slain. Then his external body,

this divine form, is stricken with grievous disease. There he stands,

the man who can consciously say to himself: “Through the inward

connection I feel with my God, I have striven to be righteous before

my God. My fate, decreed to me by this God, has placed me in the

world. It is the acts of this God which have fallen so heavily upon

me.” And his wife stands there beside him, and calls upon him

in strange words to deny his God. These words are handed down

correctly. They are one of the sayings which correspond exactly with

the Akashic record: ‘Renounce thy God, since thou hast to

suffer so much, since He has brought these sufferings upon thee, and

die!’ What endless depth lies in these words: Lose the

consciousness of the connection with thy God; then thou wilt fall out

of the Divine connection, like a leaf from the tree, and thy God can

no longer punish thee! But loss of the connection with God is at the

same time death! For as long as the Ego feels itself connected with

God, death cannot touch it. The Ego must first tear itself away from

connection with God; then only can death touch it.

According to outward

appearance everything is against righteous Job; his wife sees his

suffering and advises him to renounce God and die; his friends come

and say: ‘You must have done this or that, for God never

punishes a righteous man.’ But he is aware, as far as his

personal consciousness is concerned, that he has done nothing

unrighteous. Through the events he encounters in the external world

he stands before an immense tragedy: the tragedy of not being able to

understand human existence, of feeling himself bound up with God and

not understanding how what he is experiencing can have its source in

God.

Let us think of all

this lying with its full weight upon a human soul. Let us think of

this soul breaking forth into the words which have come down to us

from the traditional story of Job: ‘I know that my Redeemer

liveth! I know that one day I shall again be clothed with my bones,

with my skin, and that I shall look upon God with whom I am united.’

This consciousness of the indestructibility of the human

individuality breaks forth from the soul of Job in spite of all the

pain and suffering. So powerful is the consciousness of the Ego as

the inner content of the ancient Hebrew belief! But here we meet with

something in the highest degree remarkable. ‘I know that my

Redeemer liveth,’ says Job, ‘I know that one day I shall

again be covered with my skin, and that with mine eyes I shall behold

the glory of my God.’ Job brings into connection with the

Redeemer-thought the external body, skin and bones, eyes which see

physically. Strange! Suddenly, in this consciousness that stands

midway between Greek thought and Buddhism — this ancient Hebrew

consciousness — we meet a consciousness of the significance of

the physical bodily form in connection with the Redeemer-thought,

which then becomes the foundation, the basis, for the Christ-thought.

And when we take the answer of Job's wife, still more light

falls on everything Job says. ‘Renounce thy God and die.’

This signifies that he who does not renounce his God does not die.

That is implied in these words. But then, what does ‘die’

mean? To die means to throw off the physical body. External Maya

seems to say that the physical body passes over into the elements of

the earth, and, so to speak, disappears. Thus in the answer of Job's

wife there lies the following: ‘Do what is necessary that thy

physical body may disappear!’ It could not mean anything else,

or the words of Job that follow would have no sense. For man can

understand anything only if he can understand the means whereby God

has placed us in the world; if, that is, he can understand the

significance of the physical body. And Job himself says, for this too

lies in his words: ‘O, I know full well that I need not do

anything that would bring about the complete disappearance of my

physical body, for that would be only an external appearance. There

is a possibility that my body may be saved, because my Redeemer

liveth. This I cannot express otherwise than in the words: My skin,

my bones, will one day be recreated. With my eyes I shall behold the

Glory of my God. I can lawfully keep my physical body, but for this I

must have the consciousness that my Redeemer liveth.’

So in this story of

Job there comes before us for the first time a connection between the

Form of the physical body, which the Buddhist would strip off, which

sadly the Greek sees pass away, and the Ego-consciousness. We meet

for the first time with something like a prospect of deliverance for

that which the host of Gods from ancient Saturn, Sun, and Moon, down

to the Earth itself, have brought forth as the Form of the physical

body. And if the Form is to be preserved, if we are to say of it that

what has been given us of bones, skin and sense-organs is to have an

outcome, then we must add: ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth.’

This is strange, someone might now say. Does it really

follow from the story of Job that Christ awakens the dead and rescues

the bodily Form which the Greeks believed would disappear? And is

there perhaps anything in the story to indicate that for the general

evolution of humanity it is not right, in the full sense of the word,

that the external bodily Form should disappear completely? May it not

be interwoven with the whole human evolutionary process? Has this

connection a part to play in the future? Does it depend upon the

Christ-Being?

These questions are

set before us. And they mean that we shall have to widen in a certain

connection what we have so far learnt from Spiritual Science. We know

that when we pass through the gate of death we retain at least the

etheric body, but we strip off the physical body entirely; we see it

delivered up to the elements. But its Form, which has been worked

upon through millions and millions of years — is that lost in

nothingness, or is it in some way retained?

We will consider

this question in the light of the explanations you have heard today,

and tomorrow we will approach it by asking: How is the impulse given

to human evolution by the Christ related to the significance of the

external physical body — that body which throughout Earth

evolution is consigned to the grave, the fire or the air, although

the preservation of its Form is necessary for the future of mankind?

|