![[Steiner e.Lib Icon]](https://wn.rudolfsteinerelib.org/icons/pix/rsa_icon2.gif)

|

|

|

Rudolf Steiner e.Lib

|

|

|

The Riddle of Humanity

Rudolf Steiner e.Lib Document

|

|

|

The Riddle of Humanity

Schmidt Number: S-3243

On-line since: 29th July, 2002

When we speak of the great world and the small world, of the macrocosm

and the microcosm, we are referring to the whole universe and to the

human being. Goethe, for example, spoke in these terms in

Faust. He called the whole cosmos ‘the great world’,

and the human being ‘the small world.’ We have already had

many occasions to observe how manifold and complicated are the

relationships between man and the cosmos. Today I would like to remind

you of some of the things we have spoken about at various times,

connecting these with a consideration of humanity's relationship to

the cosmos. You will remember that when we spoke of the senses and of

what man, as the possessor of his senses, is, we said that the senses

lead us back to the ancient Saturn phase of evolution. That is where

we find the first impulses for the development of the senses, the

first seeds of the senses. You will find these things described again

and again in previous lecture cycles. Now, obviously, the early

seed-like phases of the senses during the Saturn period are not to be

imagined as if they already resembled the senses as we know them

today. That would be foolish. As a matter of fact, it is extremely

difficult to imagine what the senses were like during ancient Saturn

development. It is already difficult enough to picture the senses as

they were during the ancient Moon period. Even that far back in time

they were thoroughly different from the senses we know now. Today I

would like to throw some light on what the senses were like during the

ancient Moon phase of evolution. By that time they were already in

their third phase of development — Saturn, Sun, Moon.

As regards their form, the senses of today are much more dead than

were the senses of Old Moon. At that period the sense organs were much

livelier, much more full of life. Because of this they were not suited

to provide the foundations for fully conscious human life, but were

only suited to the dreamy clairvoyance of Moon man. Such clairvoyance

excluded the possibility of freedom. There was no freedom to act or to

follow impulses and desires. Humanity had to wait for the Earth phase

of evolution before it could develop the impulse to freedom. Thus, the

senses during Old Moon were not the basis for the kind of

consciousness we now have, but rather for a consciousness that was

both more dull and more imaginative than ours. As I have often

explained, it was much more like today's dream consciousness. People

generally assume that we have five senses. We know, however, that this

is not justified, but that, in truth, we must distinguish twelve human

senses. There are seven further senses that must be included with the

usual five, since they are equally relevant to earthly, human

existence. You know the usual list of the senses: sense of sight,

sense of hearing, sense of taste, sense of smell, and sense of

feeling. The last of these is often called the sense of touch and is

mixed together with the sense of warmth, although more recently there

are some who distinguish the one from the other. In earlier times

these two completely distinct senses were mixed together, confusedly,

as a single sense. The sense of touch tells whether something is hard

or soft, which has nothing to do with the sense of warmth. And so, if

one really has a sense — if I may use that word — for the

way humanity relates to the rest of the world, one will have to

distinguish twelve senses. Today I would like, once again, to describe

these twelve senses.

The sense of touch is the sense that relates us to the most material

aspect of the external world. With our sense of touch we, so to speak,

bump into the external world; through touch we are continually

involved in a coarse kind of exchange with the external world.

Nevertheless, the process of touching takes place within the

boundaries of our skin. Our skin collides with an object. What then

happens to give us a perception of the object must, as a matter of

course, take place within the boundaries of our skin, within our body.

Thus, what happens in touching, in the process of touch, happens

inside us —

The sense that we shall call the sense of life involves processes that

lie still more deeply embedded in the human organism. This sense

exists within us, but we are accustomed to ignore it, for the life

sense manifests itself indistinctly from within the human organism.

Nevertheless, throughout all our daily waking hours, the harmonious

collaboration of all the bodily organs expresses itself through the

life sense, through the state of life in us. We usually pay no

attention to it because we expect it as our natural right. We expect

to be filled with a certain feeling of well-being, with the feeling of

being alive. If our feeling of alive-ness is diminished, we try to

recover a little so that our feeling of life is refreshed again. This

vital enlivening or damping down is something we are aware of, but

generally we are too accustomed to the feeling of being alive to be

constantly aware of it. The life sense, however, is a distinct sense

in its own right. Through it we feel the life in us, precisely as we

see what is around us with our eyes. We sense ourselves through the

life sense just as we see with our eyes. Without this internal sense

of life we would know nothing about our own vital state.

What can be called the sense of movement is still more inward, more

physically inward, more bodily inward. Through feelings of well-being

or of discontent the life sense makes us conscious of the state of the

whole organism. Having a sense of movement, on the other hand, means

being able to be aware of the way parts of the body move with respect

to each another. I do not refer here to movements of the whole person

— that is something else. I am referring to movements such as the

bending of an arm or leg, or the movements of the larynx when you

speak. The sense of movement makes you aware of all these inner

movements that entail changes in the position of separate parts of the

organism.

A further sense that must be distinguished is the sense we will call

balance. We do not normally pay any attention to it. If we get dizzy

and fall, or if we feel faint, it is because the sense of balance has

been interrupted. This is exactly analogous to the way the sense of

sight is interrupted when we close our eyes. When we relate ourselves

to the world, orientating ourselves with respect to above and below

and to right and left so that we feel upright, we are employing our

sense of balance, just as we employ the sense of movement when we are

aware of internal changes of position. Our sense of balance,

therefore, is due to a distinct sense. Balance is a proper sense in

its own right.

The senses mentioned so far involve processes that remain within the

bounds of the organism. If you touch something, you have collided with

an external object, it is true, but you do not get inside it. If you

come up against a needle you will notice that it is pointed, but of

course you do not get inside the point. Instead, you prick yourself,

and that no longer has anything to do with touching. Everything that

happens, happens within the boundaries of your organism. You can touch

an object, to be sure, but everything you experience through touch

takes place within your skin. Thus, experiences of touch are internal

to the body. What you experience through the life sense is likewise

internal to the body. It does not show you what is going on somewhere

outside you; it lets you look within. Equally internal is the sense of

movement: it is not concerned with how I can walk about in the world,

but with the internal movements I make when I move part of myself or

when I speak. When I move about externally there is also internal

movement. But the two things must be distinguished from one another:

on the one hand there is my forward movement, on the other, there is

the movement of parts of me, which is internal. So the sense of

movement gives us internal perceptions, as do the senses of life and

balance. In balance, too, you perceive nothing external — rather,

you perceive yourself in your state of balance.

The first sense to take you outside yourself is the sense of smell.

With smell you already come into contact with the external world. But

you will have the feeling that smell does not take you very far

outside yourself. You do not experience much about the external world

through the sense of smell. Furthermore, people do not want to have

anything to do with the intimate connection with the world that a

developed sense of smell can give. Dogs are much more interested.

People are willing to use the sense of smell to perceive the world,

but they do not want the world to come very close. It is not a sense

through which people want to get very involved with the outer world.

With the sense of taste we get more deeply involved with the world.

When we taste sugar or salt, the experience of its qualities is

already very inward. What is external is taken inward — more so

than with smell. So there is already more of a connection established

between inner world and outer world.

The sense of sight involves us even more with the external world. In

seeing we take into ourselves more of the properties of the external

world than we do with the sense of smell. And we take yet more into

ourselves with the sense of warmth. What we see, what we perceive

through the sense of sight, remains more foreign to us than what we

perceive through the sense of warmth. The relationship to the outer

world perceived through the sense of warmth is already a very intimate

one. When we are aware of the warmth or the coldness of an object we

also experience this warmth or coldness — we experience it along

with the object. On the other hand, in experiencing the sweetness of

sugar, for example, one is not so involved with the object. In the

case of sugar we are interested in what it becomes as we taste it, not

in what it is out there in the world. Such a distinction ceases to be

possible with the sense of warmth. With warmth we are already

participating in what is within the object perceived.

When we turn to the sense of hearing, the relation to the external

world acquires another degree of intimacy. A sound tells us very much

indeed about the inner structure of an object — more than what

the sense of warmth can tell, and very much more than what sight

reveals. Sight only gives us pictures, so to speak, pictures of the

outer surface. But when a metal resonates it tells us what is going on

within it. The sense of warmth also reaches into the object. When I

take hold of something, a piece of ice, say, I am sure that the ice is

cold through and through, not just on its outer surface. When I look

at something, I can see only the colours at its outer limits, on its

surface; but when I make an object resonate, the sounds bring me into

a particular relationship with what is within it.

And the intimacy is greater still if the sounds contain meaning. Thus

we arrive at the sense of tone: perhaps it would be better to call it

the sense of speech or the sense of word. It is simply nonsense to

think that perception of words is the same as perception of sounds.

The two are as distinct and different from one another as are taste

and sight. To be sure, sounds open the inner world of objects to our

perception, but these sounds must become much more inward before they

can become meaningful words. Therefore it is a step into a deeper

intimacy with the world when we proceed from perceiving sounds through

the sense of hearing to perceiving meaning through the sense of the

word. And yet, when I perceive a mere word I am still not so

intimately connected with the object, with the external thing, as I am

connected with it when I perceive the thoughts behind the words. At

this stage, most people cease to make any distinctions. But there is a

distinction between merely perceiving words and actually perceiving

the thoughts behind the words. After all, you still can perceive words

when a phonograph — or writing, for that matter — has

separated them from their thinker. But a sense that goes deeper than

the usual word sense must come into play before I can come into a

living relationship with the being that is forming the words, before I

can enter through the words and transpose myself directly into the

being that is doing the thinking and forming the concepts. That

further step calls for the sense I would like to call the sense of

thought. And there is another sense that gives an even more intimate

sense of the outer world than the sense of thought. It is the sense

that enables you to feel another being as yourself and that makes it

possible to be aware of yourself while at one with another being. That

is what happens if one turns one's thinking, one's living thinking,

towards the being of another. Through living thinking one can behold

the I of this being: the sense of the

I .

You see, it really is necessary to distinguish between the ego sense,

which makes you aware of the I of another person,

and the awareness of yourself. The difference is not just that in one

case you are aware of your own I and, in the other,

of someone else's I . The two perceptions come from

different sources. The seeds of our ability to distinguish one another

were sown on Old Saturn. The beginnings of this sense were implanted

in us then. The basis of your being able to perceive another person as

an I was established on Old Saturn. But it was not

until the Earth stage of evolution that you obtained your own

I ; so the ego sense is not to be identified with

the I that ensouls you from within. The two must be

strictly distinguished from one another. When we speak of the ego

sense, we are referring to the ability of one person to be aware of

the I of another.

As you know, I have never spoken of materialistic science without

acknowledging its truth and its greatness. I have given lectures here

that were for the express purpose of appreciating materialistic

science fully. But, having appreciated it, one must deepen one's

knowledge of materialistic science so lovingly that one also can hold

up its shadow side with a loving hand. The materialistic science of

today is just beginning to bring its thoughts about the senses into

some kind of order. The physiologists are finally recognising and

distinguishing the senses of life, of movement and of balance from one

another, and they have begun to treat the senses of warmth and touch

separately. The other senses about which we have been speaking are not

recognised by our externally-orientated, material science. And so I

ask you to carefully distinguish the ability to be aware of another

I from the ability you could call the consciousness

of self. With respect to this distinction, my deep love of material

science forces me to make an observation, for a deep love of material

science also enables one to see what is going on: today's material

science is afflicted with stupidity. It turns stupid when it tries to

describe what happens when someone uses his ego sense. Our material

science would have us believe that when one person meets another he

unconsciously deduces from the other's gestures, facial expressions,

and the like, that there is another I present

— that the awareness of another I is really a subconscious

deduction. This is utter nonsense! In truth, when we meet someone and

perceive their I we perceive it just as directly as

we perceive a colour. It really is thick-headed to believe that the

presence of another I is deduced from bodily

perceptions, for this obscures the truth that humans have a special,

higher sense for perceiving the I of another.

The I of another is perceived directly by the ego

sense, just as brightness and darkness and colours are perceived

through the eyes. It is a particular sense that relates us to another

I . This is something that has to be experienced.

Just as a colour affects me directly through my eyes, so another

person's I affects me directly through my ego

sense. At the appropriate time we will discuss the sense organ for the

ego sense in the same way that we could discuss the sense organs of

seeing, of sight. With sight it is simply easier to refer to material

manifestations than it is in the case of the ego sense, but each sense

has its own particular organ.

If you view your senses from a certain perspective you can say: each

sense particularises and differentiates my organism. There is a real

differentiation, for seeing is not the same as perception of tone,

perception of tone is different from hearing, hearing is not the same

as perception of thought, perception of thought is not touching. Each

of these senses demarcates a separate and particular region of the

human being. It is this separation of each into its special sphere to

which I want you to pay especially close attention, for it is this

separation that makes it possible to picture the senses as a circle

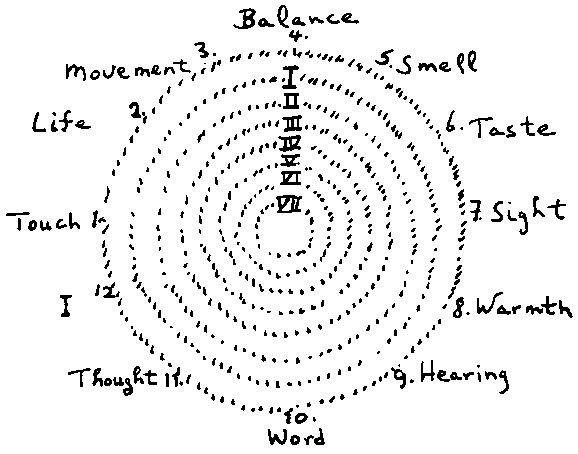

divided into twelve distinct regions. (See diagram.)

The situation of these powers of perception is different from the

situation of forces that could be said to reside more deeply embedded

within us. Seeing is bound up with the eyes and these constitute a

particular region of a human being. Hearing is bound up with the

organs of hearing, at least principally so, but it needs more besides

— hearing involves much more of the organism than just the ear,

which is what is normally thought of as the region of hearing. And

life flows equally through each of these regions of the senses. The

eye is alive, the ear is alive, that which is the foundation of all

the senses is alive; the basis of touch is alive — all of it is

alive. Life resides in all the senses; it flows through all the

regions of the senses.

If we look more closely at this life, it also proves to be

differentiated. There is not just one life process. And you must also

distinguish what we have been calling the sense of life, through which

we perceive our own vital state, from the subject of our present

discussion. What I am talking about now is the very life that flows

through us. That life also differentiates itself within us. It does so

in the following manner (see diagram). The twelve regions of the

twelve senses are to be pictured as being static, at rest within the

organism. But life pulsates through the whole organism, and this life

is manifested in various ways. First of all there is breathing, a

manifestation of life necessary to all living things. Every living

organism must enter into a breathing relationship with the external

world. Today I cannot go into the details of how this differs for

animals, plants and human beings, but will only point out that every

living thing must have its way of breathing. The breathing of a human

being is perpetually being renewed by what he takes in from the outer

world, and this benefits all the regions associated with the senses.

The sense of smell could not manifest itself — neither sight, nor

the sense of tone — if the benefits of breathing did not enliven

it. Thus, I must assign ‘breathing’ to every sense. We

breathe — that is one process — but the benefits of that

process of breathing flow to all the senses.

The second process we can distinguish is warming. This occurs along

with breathing, but it is a separate process. Warming, the inner

process of warming something through, is the second of the

life-sustaining processes. The third process that sustains life is

nourishment. So here we have three ways in which life comes to us from

without: breathing, warming, nourishing. The outer world is part of

each of these. Something must be there to be breathed — in the

case of humans, and also animals, that substance is air. Warming

requires a certain amount of warmth in the surroundings; we interact

with it. Just think how impossible it would be for you to maintain

proper inner warmth if the temperature of your surroundings were much

hotter or much colder. If it were one hundred degrees lower your

warmth processes would cease, they would not be possible; at one

hundred degrees hotter you would do more than just sweat! Similarly,

we need food to nourish us as long as we are considering the life

processes in their earthly aspects.

At this stage, the life processes take us deeper into the internal

world. We now find processes that re-form what has been taken in from

outside — processes that transform and internalise it. To

characterise this re-forming, I would like to use the same expressions

that we have used on previous occasions. Our scientists are not yet

aware of these things and therefore have no names for them, so we must

formulate our own. The purely inner process that is the basis of the

re-forming of what we take in from outside us can be seen to be

fourfold. Following the process of nourishing, the first internal

process is the process of secretion, of elimination. When the

nourishment we have taken in is distributed to our body, this is

already the process of secretion; through the process of secretion it

becomes part of our organism. The process of elimination does not just

work outward, it also separates out that part of our nourishment that

is to be absorbed into us. Excretion and absorption are two sides of

the processes by which organs of secretion deal with our nourishment.

One part of the secretion performed by organs of digestion separates

out nutriments by sending them into the organism. Whatever is thus

secreted into the organism must remain connected with the life

processes, and this involves a further process which we will call

maintaining. But for there to be life, it is not enough for what is

taken in to be maintained, there also must be growth. Every living

thing depends on a process of inner growth: a process of growth, taken

in the widest sense. Growth processes are part of life; both

nourishment and growth are part of life.

And, finally, life on earth includes reproducing the whole being; the

process of growth only requires that one part produce another part.

Reproduction produces the whole individual being and is a higher

process than mere growth.

There are no further life processes beyond these seven. Life divides

into seven definite processes. But, since they serve all twelve of the

sense zones, we cannot assign definite regions to these-the seven life

processes enliven all the sense zones. Therefore, when we look at the

way the seven relate to the twelve we see that we have 1. Breathing,

2. Warming, 3. Nourishing, 4. Secretion, 5. Maintaining, 6. Growth, 7.

Reproduction. These are distinct processes, but all of them relate to

each of the senses and flow through each of the senses: their

relationship with the senses is a mobile one. (See drawing.) The human

being, the living human being, must be pictured as having twelve

separate sense-zones through which a sevenfold life is pulsing, a

mobile, sevenfold life. If you ascribe the signs of the zodiac to the

twelve zones, then you have a picture of the macrocosm; if you ascribe

a sense to each zone, you have the microcosm. If you assign a planet

to each of the life processes, you have a picture of the macrocosm; as

the life processes, they embody the microcosm. And the mobile life

processes are related to the fixed zones of the senses in the same way

that, in the macrocosm, the planets are related to the zones of the

zodiac — they move unceasingly through them, they flow through

them. And so you see another sense in which man is a macrocosm.

Now, someone who is thoroughly versed in contemporary physiology and

knows how physiology is pursued today could well say to us: ‘This

is all just clever tricks; it is always possible to find relations

between things. And if a person has divided up the senses so as to

come out with twelve, of course he can relate them to the twelve signs

of the zodiac; and the same goes for distinguishing seven life

processes which can then be related to the seven planets.’ To put

it bluntly, such a person might believe that all this is the product

of fantasy. But this is truly not the case, for the human being of

today is the result of a slow process of unfolding and development.

During Old Moon, the human senses were not as they are today. As I

said, they provided the basis for the ancient, dreamlike clairvoyance

of Old Moon existence. Today's senses are more dead than those of Old

Moon. They are less united into a single whole and are more separated

from the sevenfold unity of the life processes. The senses of Old Moon

were themselves more akin to the life processes. Today, seeing and

hearing are quite dead, they involve processes that occur at the

periphery of our being.

Perception, however, was not nearly so dead on Old Moon. Take any of

the senses, the sense of taste, for example. I imagine all of you know

what that is like on Earth. During the Moon era it was rather

different. At that time a person was not so separated from his outer

surroundings as he is nowadays. For us, sugar is something out there:

to connect with it we have to lick something and then inner processes

have to take place. There is a clear distinction between the

subjective and the objective. It was not like this during Old Moon.

Then, the process was much more filled with life and there was not

such a clear distinction between subjective and objective. The process

of tasting was more like a life process, more like — say —

breathing. When we breathe, something real happens in us. We breathe

in air but, in so doing, all the blood-forming processes in us are

affected-all these processes are part of breathing, which is one of

the seven life processes and does not permit of such clear

distinctions between subject and object. In this case, what is outside

and what is within must be taken together: air outside, air within.

And something real happens through the process of breathing, much more

real than what happens when we taste something. When we taste, enough

happens to provide a basis for the typical consciousness of today, but

on Old Moon tasting was much more similar to the dreamlike process

that breathing is for us today. We are not nearly so aware of

ourselves in our breathing as we are when we taste something. But on

Old Moon, tasting was like breathing is for us now. Man on ancient

Moon experienced no more of his tasting than we experience of our

breathing, nor did he feel a need for it to be otherwise. The human

being had not yet become a gourmet, nor could he become one, for

tasting depended on certain internal happenings that were connected

with his processes of maintenance, with his continued existence on Old

Moon.

Sight, the process of seeing, was also different on Old Moon. Then one

did not simply look at external objects, perceiving the colour as

something outside oneself. Instead, the eye penetrated into the colour

and the colour entered through the eyes, helping to maintain the life

of the viewer. The eye was a kind of organ for breathing colour. The

state of our life was affected by how we related to the outer world

through our eyes and by the perceptual processes of the eyes. On Old

Moon, we expanded upon entering a blue region and contracted if we

ventured into a red region: expanding-contracting,

expanding-contracting. Colour affected us that much. Similarly, all

the other senses also had a more living connection, both with the

outer world and with the inner world of the perceiver, a connection

such as the life processes have today.

And what was the sense of another ego like on Old Moon? There could

not have been any such sense on Old Moon, for it is only since the

Earth stage of development that the I has begun to

dwell within us. The sense of thought, of living thought as I

previously described it, is also connected with Earth consciousness.

Our sense of thought did not yet exist on Old Moon. Neither did

humanity speak. And since there was nothing like our perception of

each other's speech, the sense of word was also absent. In earlier

times the word lived as the Logos which streamed through the whole

world, including humanity. It had significance to man, but was not

perceived by him. The sense of hearing was already developing, though,

and was much more filled with life than the hearing of today. That

sense has, so to speak, now come to rest on Earth, to a standstill.

When we listen, we stay quite still, at least as a rule. Unless a

sound does something of the order of bursting an eardrum, hearing does

not change anything in our organism. We remain at rest within

ourselves and perceive the sounds, the tones. This is not how things

were during Old Moon. Then the tones really came close. They were

heard, but that hearing involved being inwardly pervaded by the tones,

it involved inwardly vibrating with the sounds and actively

participating in their creation. Man participated actively in the

production of what we call the Cosmic Word, but he was not aware of

it. Thus we cannot call it a sense, properly speaking, although Moon

man participated in a living fashion in the sounds that are the basis

of today's hearing. If what we hear today as music had been played on

Old Moon, there would have been more than just an outward dancing! If

that had happened, all the internal organs, with few exceptions, would

have reacted the way my larynx: and related organs react when I use

them to produce a tone. Thus, it was not a conscious process, but a life

process in which one actively participated, for the whole inner man

was brought into vibration. These vibrations were harmonious or

dissonant, and the vibration was perceived in the tones.

The sense of warmth was also a life process. Today we are

comparatively calm when we regard our surroundings; we just notice

that it is warm or cold outside. Of course we experience it to a mild

degree, but not as during Old Moon, when a rise or fall in temperature

was experienced so intensely that one's whole sense of life changed.

In other words, the participation was much more intense: just as one

vibrated with a tone, one experienced oneself getting inwardly cooler

or warmer.

I already have described what the sense of sight was like on Old Moon.

There was a living involvement with colours. Some colours caused us to

enlarge our body, others to contract it. Today we can only experience

this symbolically, if at all. We no longer collapse when confronted

with red, nor do we inflate when surrounded by blue — but we did

do this on Old Moon. The sense of taste has also been described

already.

The sense of smell was intimately bound up with the life processes on

Old Moon. There was also a sense of balance, it was already needed.

And the sense of movement was much livelier. Today we have more or

less come to rest in ourselves — we are more or less dead. We

move our limbs, but not much of us actually vibrates. But just imagine

all the movement there was to be aware of on Old Moon when tones

generated inner movement.

Now, as for the sense of life, you will gather from what I have been

saying that no sense analogous to our sense of life could have been

present on Old Moon. At that time one was altogether immersed in life,

in life as a whole. The skin was not the boundary of inner life. Life

was something in which one swam. There was no need for a special sense

of life since all the organs that today are sense organs were organs

of life in those times — they were alive and they provided

consciousness of that life. So there was no need for a special sense

of life on Old Moon.

The sense of touch came into being along with the mineral world, which

is a result of Earth evolution. On Old Moon there was nothing

analogous to the sense of touch that we have developed here on Earth

in conjunction with the mineral realm. There was no such sense on Old

Moon where it was no more needed than was a sense of life.

If we count how many of our senses were already to be found on Old

Moon as organs of life, we find there were seven. Manifestations of

life are always sevenfold. The five senses unique to Earth evolution

fall away when we consider Moon man. They join the other seven later,

during our Earth evolution, to make up the twelve senses, because the

Earth-senses have become fixed zones as have the regions of the

zodiac. There were only seven senses on Old Moon, for then the senses

were still mobile and full of life. Thus there was a sevenfold life on

Old Moon, a life in which the senses were still immersed.

This account is the result of living observations of a super-sensible

world which — initially — is beyond the limits of earthly

perception. What has been said is just a small, an elementary part of

all that needs to be said to show that our account is not the product

of arbitrary whims. The more one presses on and achieves a vision of

cosmic secrets, the more one sees that all this talk about the

relation of seven to twelve is not just a game. This relationship

really can be traced through all the manifestations of life. The

relation of the fixed stars to the planets is a necessary outer

expression of it and reveals one of the mysteries of number that

underlie the cosmos. And the relationship of the number twelve to the

number seven expresses one of the mysteries of existence, the mystery

of how man, as bearer of the senses and faculties of perception, is

related to man as the bearer of life. The number twelve is connected

with the mystery of how we are able to carry an I .

The establishment of twelve senses, each at rest in its own proper

region, provided a basis for earthly self-awareness. The fact that the

senses of Old Moon were still organs of life meant that Moon man could

possess an astral body, but not an I ; for then the

seven senses were still organs of life and only provided the basis for

the astral body. The number seven is concerned with the mysteries of

the astral body just as the number twelve is concerned with the

mysteries of the human I .

|

|

Last Modified: 20-May-2025

|

The Rudolf Steiner e.Lib is maintained by:

The e.Librarian:

elibrarian@elib.com

|

|

|

![[Spacing]](https://wn.rudolfsteinerelib.org/AIcons/images/space_72.gif)

|

|