Lecture V

Dornach, 28th November 1916

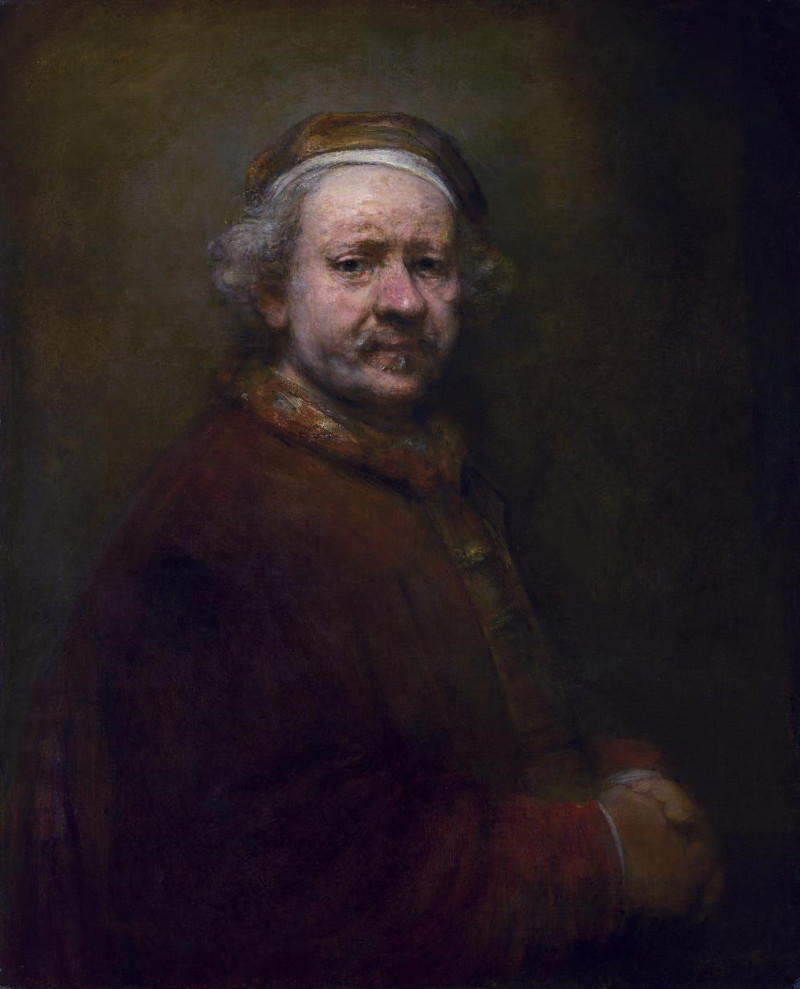

Rembrandt Self-portrait 1639 |

Continuing our series of

lantern lectures, we will today pick out a single artist — albeit

one of the very greatest in the artistic evolution of humanity. I refer

to Rembrandt.

In this case the former

kind of introduction, indicating the historic background of the artist's

life and times, would be a little out of place. With an individual artist

such as Rembrandt, it is more important to give ourselves up to the

immediate impression of his works — so far as is possible through

some few reproductions. For only when we bring before our souls in sequence

at least a few of his main works, — only then do we realise how

unique a figure is Rembrandt in the history of mankind. We should, indeed,

be adopting a false method if we tried — as in the case of

Michelangelo, Raphael and others — to reveal the background of his

creations more from the point of view of the history of his times. For

Rembrandt, as a human phenomenon, stands, to a great extent, isolated.

He grows out of the broad foundations of the race. In his case it is far

more important to see how he himself stands in the stream of evolution

— to see what radiates from him into the stream of evolution —

than to attempt to describe him as a product of it.

This is the essential point

— to recognise the immense originality which is peculiar to

Rembrandt. As an isolated phenomenon of history, he grows out of the broad

mass of the European people, once more bearing witness to the truth that

when we contemplate the creative work of human individualities, we cannot

simply construct a succession of historic causes and effects. Sooner

or later we must realise the fact that just as one plant in the garden,

standing beside another in a row, has not its cause in the neighbouring

plant, so the successive phenomena of history have not always their

causes in the preceding ones.

As the plants grow forth

from the common soil under the influence of the common sunlight, so

do the phenomena of history grow from cut a common soil, conjured forth

by the activity of the Spiritual that ensouls humanity.

In Rembrandt we must look

for something elemental and original. Many people in Mid-Europe began

to feel this very strongly about the end of the eighties and the beginnings

of the nineties of last century. It was curious to see what a far-reaching

influence a certain book had which was published about that time. The

book was not exactly about Rembrandt, but took its start from

Rembrandt.

When I left Vienna at the

end of the 1880s, I went out of an atmosphere in which everyone was

reading and discussing this book Rembrandt as an Educator, by a

German. Such was its title. I found the same atmosphere when I

came to Weimar, and it went on for two or three years longer. Everyone

was reading Rembrandt as an Educator. I myself — if I may

interpolate this remark — found the book to some extent antipathetic.

To me it was as though the author — undoubtedly a man of keen

perceptions — had written down on scraps of paper in the course

of time, all manner of ideas that had occurred to him. He might then

have thrown them all together into a little box, shaken them up, and

taken them out at random and so compiled his book. So confused were

all the thoughts — so little logical sequence — so little

system was there in the book.

However unpleasing from

this point of view, the book nonetheless expressed something of great

significance, especially so for the close of the 19th century. People

investigated in all directions to discover who the unknown author might

be. He had at any rate succeeded in writing out of the hearts of very

many people. He felt that the spiritual and intellectual life of men

had lost connection, as it were, with the mother-soil of spiritual life.

Human souls no longer had the force to penetrate to the heart and center

of the Cosmic Order, to draw from thence something which could give

them inner fullness and satisfaction. The anonymous writer was everywhere

referred to as der Rembrandt Deutsche, — the Rembrandt —

German. His desire was to bring the life of the human soul back again to

an elemental and original feeling of what pulsates as the underlying

heart of things — even in the phenomena of the great world. He

wanted to bring them thoughts of an awakening — calling out aloud

to mankind: “Remember once more what lives in the elemental depths

of the soul! You have lost touch; you are trifling everywhere on the

surface of things — in science and scholarship, and even in your

cultivation of artistic taste. You have lost the Mother-Earth of spiritual

life. Remember it once more!”

To this end he would take

his start from the phenomenon of Rembrandt and he therefore called his

book Rembrandt as an Educator. He found the conceptions and

ideas of men floating about on the surface; but in Rembrandt he saw

an individuality who had drawn from the very depths of elemental human

forces.

If you look back on our

lectures here at Dornach during the last few weeks, you will realise

— what we cannot but realise — that the inner intensity of

spiritual life had declined considerably in Europe in the last decades of

the 19th century. In all directions it had become essentially a culture on

the surface. Even the great figures of the immediate past were appreciated

only in a superficial way. What, after all, did the late 19th century

(I refer to wider circles, a few individuals always excepted) understand

of such writers as Goethe or Lessing? They understood practically nothing

of their greatest works.

The

“Rembrandt-Deutsche”

felt, as I have said, that the soul's power of perception must be brought

to feel and realise once more all that is elemental, all that is truly

great in human evolution. True, if we feel, perhaps, in a still deeper

way than he, what was and still is needful for our age, we cannot go

all the way with him. Indeed, his limitations — bowed themselves

in the subsequent course of his life. There was a deep sincerity of

feeling in the “Rembrandt-Deutsche;” yet, after all, he

was too much a child of his age to realise that a renewal of all spiritual

life was necessary by a discovery of those fundamental sources which

we, in our movement of Spiritual Science, are trying now to bring before

our souls. All people of that time passed by unheeding — passed

by what was “in the air,” if I may use the trivial expression:

the need for a spiritual-scientific movement. Most of them, after all,

continue to do so to this day.

The

“Rembrandt-Deutsche”

made a brave beginning. “Look,” he said, “look what

it means to wrest one's way through to such resources of humanity as

Rembrandt reached!” Yet when all this had been living in his soul,

he probably fell more and more into a kind of despair — despair

of the presence of any such living sources in the evolution of mankind.

Eventually he went over to Catholicism. Thus, after all, he tried to find

in something from the past — in old tradition — a consolation

for the vain quest on which he had so bravely started in his book. His

impulse did not carry him far enough to reach that spiritual life which

is needed to sustain the future. None the less, we cannot but feel with

him what he felt about Rembrandt.

(I may add that the name

of the “Rembrandt-Deutsche” afterwards became known; his

name was Langbehn.)

Rembrandt is not at all

dependent on that artistic movement which I have characterised in recent

lectures as the Southern European stream. He is even less dependent than

Dürer was. Truly, one might say that not in a single fiber of his

soul was he in any way dependent as an artist on the Latin, Southern

element. He stands on his own ground entirely, creating out of the

Mid-European life — out of a source of life which he draws from the

deep well-springs of the people. What was the time when Rembrandt lived

and worked? It was when the Thirty-Years' War was ravaging Mid-Europe.

Rembrandt was born in 1606;

in 1613 the Thirty-Years' War began. Thus we may say that while the

more southern nations of Middle Europe were being massacred in this

War, Rembrandt, in his North-Western corner of the land, was bringing

forth the unique creations of his genius out of the very essence of

Mid-European humanity. He never even saw Italy. He had no relation to

any nature like the Italian. He fertilised his imagination simply and

solely out of the Netherlands nature that surrounded him. He made no

studies as other painters of his country did — studies of Italian

pictures or anything of that kind. Rembrandt stands out as the

arch-representative of those who felt themselves in the 17th century so

completely — albeit unconsciously — as citizens of the new

Fifth post-Atlantean age.

Let us pass in review before

our souls what had happened from a certain moment onward until Rembrandt's

time. Hermann Grimm, who undoubtedly had a feeling for such things,

considered the creations of Art as the purest flowers that mark the

historic evolution of mankind. From the aspect of artistic history,

artistic evolution, he threw many a beautiful and brilliant search-light

on the history of Europe — notably in that time when the Fourth

post-Atlantean age was playing over into the Fifth. We ourselves, in

recent lantern lectures, have brought before our souls the flowering

of artistic life in that age. Hermann Grimm rightly says that to understand

what took its start in that period we must go back to the Carolingian

era. Nothing can teach us to understand so well what was living in the

age of Charlemagne as the Song of Valthari, written by a monk of St.

Gall in the 10th century, and relating how Mid-Europe was overwhelmed

from Italy, telling of all the destinies that overcame Mid- Europe.

(In style and form, however, the Song of Walthari — like many

other works of Art which we have shown — betrays strong Latin,

Roman influences.)

Then we come to the gradual

emerging of a new age. We find, developing in Mid-Europe, the Latin

element in architecture and sculpture. We find the gradual penetration

of the Gothic. We witness the life of this Gothic and Latin Art in the time

of the poets in Wolfram von Eschenbach, and Walther von der Vogelweide.

And we see how the Mid-European freedom of the cities — the culture

of the free cities — comes to expression in the works —

especially in the domain of sculpture — which we showed last time.

At length we come to the Mid-European Reformation, expressing itself in

the great figures of Albrecht Dürer, Holbein and others. Then, as we

indicated when speaking of Michelangelo, there came the

Counter-Reformation, spreading out over all Europe.

Once more, this is visible

in the realm of Art. Hermann Grimm rightly remarks that throughout this

period, when the powers of mighty States were overwhelming Europe, sweeping

away the political individualities, in this period of the great

Principalities, there arose what is made visible in the Art of Rubens,

Van Dyck, Velasquez. With all their greatness, when we call to mind these

names we cannot but find expressed in them something connected with the

Counter-Reformation — with the will to break up the Mid-European

people.

Rembrandt, on the other

hand, is an artist who makes felt — as an artist — something

that contains the highest and strongest assertion of human individuality

and human freedom, and his creations spring from the deep originality

of this same people.

It is wonderful to see

how in Rembrandt has continued what I have already explained in the

case of Dürer — the weaving in the elemental play of light

and darkness. What Goethe afterwards achieved for Science (although

Science to this day does not accept it, not having yet advanced so far

— but it will become so in good time) — the discovery in

light and darkness of an elemental weaving on the waves of which the

true origin of color itself is to be sought — this, I would say,

lights up in the realm of Art for the first time in Dürer and finds

its highest expression in Rembrandt.

The greatness of the Italian

Masters of painting lay in the fact that they raised the individual

appearance to the sublime — to the typical. Rembrandt is the faithful

observer of the immediate reality. But he observes it not in the spirit

of Classical antiquity, for he belongs to the Fifth and not to the Fourth

post-Atlantean age.

How does Rembrandt observe

the reality? He confronts the object as an outsider — really and

truly as an outsider. Fundamentally speaking, even Leonardo, Michelangelo

and Raphael, living as they did in the Fifth post-Atlantean age, could do

no other than confront the object as men stand outside it. But they still

let themselves be fertilised by what came over to them from antiquity.

And thus, if I may say so, it was only half-outwardly that they confronted

the object. Rembrandt confronted it altogether outwardly, and yet in

such a way as to bring it — albeit from without — all his

own full inwardness of soul. But to bring inwardness to the outer object

in this way is not to carry all manner of things into it out of the

egoism of one's human personality. It is, rather, to be able to live

with that which works and weaves in space.

Rembrandt was a man who

wrestled on and on for decades, — we might almost say, from period

to period of five years, and his pictures bear witness to his continual

wrestling and his constant progress. This wrestling essentially consists

in the ever more perfect working out of light and darkness. Color to

him is only that which is born, as it were, out of the light and the

darkness.

What I said of Dürer

— that he looked not for the color which wells forth from within

the object, but for that color which is cast on it from outside —

applies in a still higher degree to Rembrandt. Rembrandt lives in the

surging and weaving of the light and dark. Hence he delights to observe

how the play of light and dark brings forth its remarkable plastic painting

effects in a crowd of figures. The Southern painters took their start

from composition. Rembrandt does not do this, though in the course of

his life, because of the elemental forces working in him so strongly,

he rises to the possibility of a certain composition. Rembrandt simply

sets down his figures; he lets them stand there and then he lives and

weaves in the element of light and shadow, tracing it with inner joy

as it pours itself out over the figures. And as he does so, in the very

life and movement of the light and darkness, a Cosmic, universal principle

of composition comes into his pictures.

So we see Rembrandt (if

I may so describe it) painting plastically but painting with light and

darkness. And by this means, although he only directs his gaze to the

outer reality — not to be the sublimer truth like the South-European

painters, but to the actual reality — he still lifts his characters

to a spiritual height. For that which floods through the realms of space as

light and weaves in them is the element we must always seek in Rembrandt;

by virtue of it he is the great and original spirit that he is.

You will recognise this

if you let pass before your mind's eye the whole succession of these

pictures. Rembrandt is first of all an observer, trying faithfully to

reproduce what Nature puts before him.

Then he gets nearer and

nearer to the secret of creating out of the light and the darkness,

until at length his figures only provide him with the occasion, as it

were, to reveal the working of the pure distribution of light and darkness

in the realm of space. Then he is able to reveal the mysterious fashioning

of sublimer forms out of the light and darkness. The plastic forms of

outer reality only provide him with the opportunity. We see emerging more

and more in Rembrandt's work as time goes on, the boldest imaginable

distributions of light and dark. When we stand face to face with his

creations we have the feeling: all these are no mere figures that stood

before him in space, as models or the like. The essential thing is

altogether different; it is something that hovers over the figures. The

figures only provide the occasion for what Rembrandt was essentially

creating. He created his great works by using his figures, as it were, to

catch the light. The figures give him the opportunity to seize the light.

The essential is the play of light and darkness which the figures enable

him to grasp. The figures merely stand there as a background; the real

work of Art springs from this intangible element which he attains by

means of the figures.

To look in Rembrandt's

works for the particular subjects which the pictures represent, is to

look past the essential work of Art. It is only when we contemplate

what is poured out over the figures that we see what is essential in

Rembrandt. The figures are no more than the medium for what is poured

out over them.

Of such a nature is the

delicate, intimate quality of the creations especially of his middle

period. Unfortunately we cannot show this, because the reproductions

are in black and white; but it is most interesting to see in the middle

period of his work how really the colors in his pictures are created

out of light and shade. The colors are everywhere born out of the light

and the darkness. This artistic conception becomes so strong in Rembrandt

that towards the end of his life's work, color recedes, as it were,

into the background, and all painting becomes for him a problem of light

and darkness.

It is deeply touching from

a human point of view, to witness what wrestles its way through to outward

existence from decade to decade in Rembrandt's work. For it is undeniable

— great as was his talent, his artistic genius from the very first

— he was not yet profound; he could not yet reach into the depths

of things. What he created to begin with is great in its way, yet it

somehow is lacking in depth.

Then about 1642, he suffered

a grievous loss — a loss for his whole life. He lost the wife

whom he loved so tenderly, and with whom he was so united that she was

really like a second life to him. But this loss became for Rembrandt

the source of a great, an infinite deepening of soul. Thus we see how

his creations gain in depth from this time onward — grow infinitely

richer in soul-content than before. Henceforth it is no longer merely

Rembrandt, the man of genius — henceforth it is no longer merely

Rembrandt, the man of genius — henceforth it is Rembrandt deepened

in his own inner life and being.

Considering Rembrandt

comprehensively, we must say that here at last we have the painter of the

beginning of the Fifth post-Atlantean epoch in the fullest sense of the

word. For as you know, we describe the basic character of this epoch when

we say that the Spiritual Soul, above all, is now wrestling its way into

existence. What does this signify for Art? It signifies that the artist

must stand over against his object from without. He lets the world work

upon him objectively, yet in such a way that there is still a universal

spirit in his contemplation, for otherwise he would be creating merely out

of human egoism. The very fact that he confronts the world, and even

man himself, as an outer object, gives him the possibility of seeing

infinitely much that could not be seen in former ages.

What, after all, would

be the meaning of Art if it were only to produce the reality as human

beings see it in ordinary life? It is the very purpose of Art to reproduce

what is not seen in the everyday life.

Now it is natural in the

epoch of development of the conscious Spiritual Soul that man should turn

his attention, above all, to man himself and to all that is expressible

through man. The artist of the Fourth post-Atlantean age, as I have

so often told you, created more out of an inner feeling of himself —

out of an inward experience of his own being. The artist of the Fifth

post-Atlantean age — and this is true in the highest degree of

Rembrandt — creates from outward, contemplative vision. But this

signifies for man an artistic process of self-knowledge. And I think

we are pointing to no matter of chance when we recall the fact that

Rembrandt painted so many portraits of himself. I think there is a deep

and significant meaning in the fact that he had to seek again and again

for self-knowledge as an artist. His own form was not merely the most

convenient model at his disposal — certainly it was not the most

beautiful, for Rembrandt was not a handsome man. No, for him the important

thing was to become progressively aware of the harmony between what

lives within and what can be observed from without — to become

aware of this harmony at that very place where it can best be studied

— in the self-portrait.

Undoubtedly there is a

deeper meaning in the fact that the first great painter of the Fifth

post-Atlantean age painted so many portraits of himself.

We might continue for a

long time, my dear friends, making one observation or another about

Rembrandt. The result would only be to make us realise more and more

how he stands out as an isolated phenomenon through his age, though

in this isolation he creates out of the very fountain-head, out of the

well-spring of Mid-European spiritual life. For Rembrandt creates out

of the spirit which is characteristic of Mid-Europe. To create, to look

at the outward reality, not merely seeking to observe it realistically,

but with a gaze that fertilizes itself with that by which man's gaze

can, indeed, be fertilized — with the surging, weaving, elemental

world. And for the painter, this signifies the light and dark, surging

upon the waves of color, till the outward reality is merely the occasion

to unfold this living and weaving in the light and dark and in the world

of color.

We will now consider a

few of Rembrandt's characteristic pictures, and see how these things

can be traced in his works:

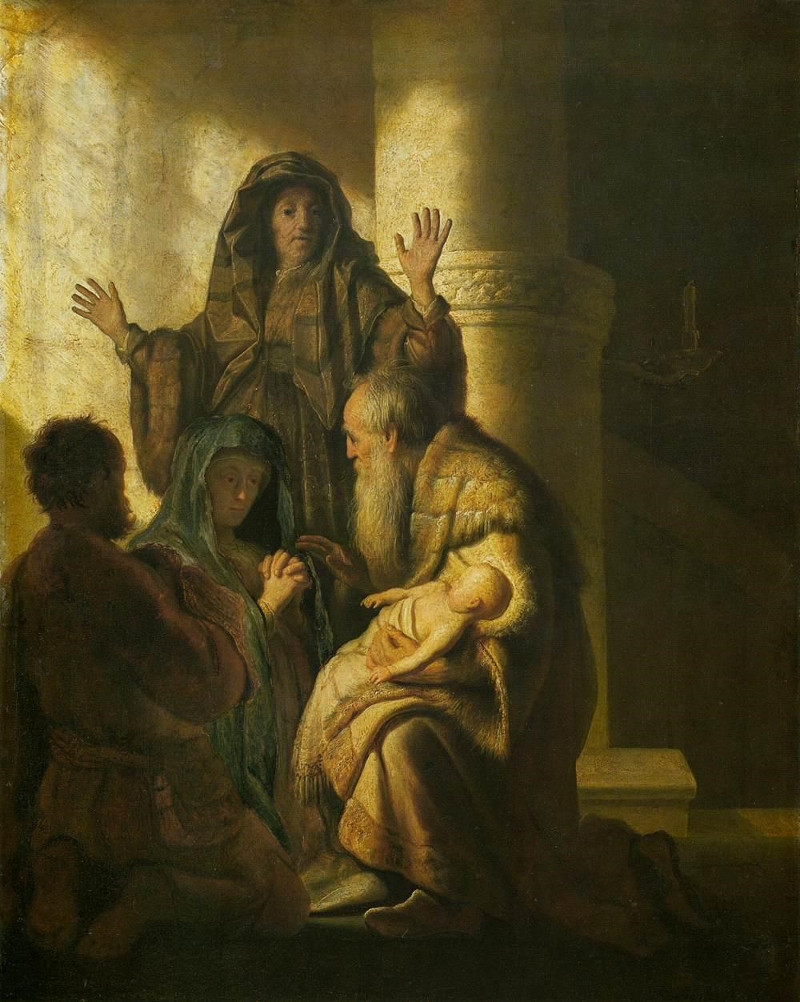

496. Presentation of Jesus in the Temple. (Galerie

Weber. Hamburg.)

Here you see at once how

what I indicated just now shows itself in actuality. In Rembrandt's

work, even when we stand before the colored paintings, we have the feeling

that what lives in color is already there potentially in the light and

shade. This must always be borne in mind.

When we let this or any

other pictures of Biblical history by Rembrandt work upon our souls, we

are struck by a peculiar difference between him and Rubens, for instance,

or the Italian Masters. Their presentations of the Biblical figures

are always somehow connected with the sacred Legends. Rembrandt's are

quite obviously the work of a man who reads the Bible for himself.

We can remember that the

time of his creative work was near the climax of that period when Roman

Catholicism, and, above all, Jesuitism, was waging an inexorable war

on all Bible-reading. Bible-reading was anathema; it was forbidden.

Meanwhile, on this Dutch soil which had just freed itself from Southern

influence and Southern rulership, there arose the strong impulse to

go to the Bible itself. They drew their inner experience from the Bible

itself — not merely from Catholic legend and tradition. Such was

the inspiration of the scenes which Rembrandt treats so wonderfully

with his rays of light and dark.

497. Samson and Delilah, 1628.(Kaiser Friedrich Museum.

Berlin.)

498. Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus, 1629.

(Paris.)

528. Portrait of Himself. (The Hague.)

Even the dress is arranged

in such a way as to express his favorite element of light and shadow.

He even liked to use a metal collar on which the light could glisten.

499. Holy Family, 1630 or 1631.(Alto Pinakothek.

Munich.)

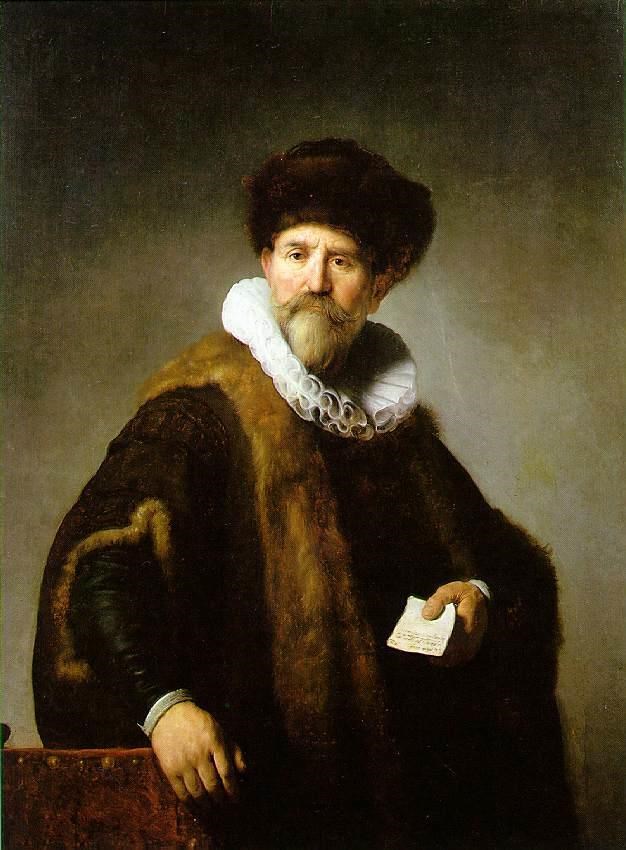

500. Portrait of Nicholas Ruts, 1631.(London.)

This portrait will certainly

confirm what I said just now, and it will show you another thing at

the same time. Under the influence of his artistic way of feeling —

although the reality is by no means lifted into realms of fancy —

the life of the soul comes to expression with great depth.

501. Mother of Jacob de Wet. (Vienna.)

The purest study in light

and darkness. Here you will feel what I tried to characterise briefly in

the introduction. All that you see here — the architectural and all

the other features — merely provided the occasion for the real work

of Art, which lies in the distribution of the light itself.

502a. Philosopher in Meditation. (Louvre. Paris.)

502b. Philosopher in Meditation by Koninck (Rembrandt

School)

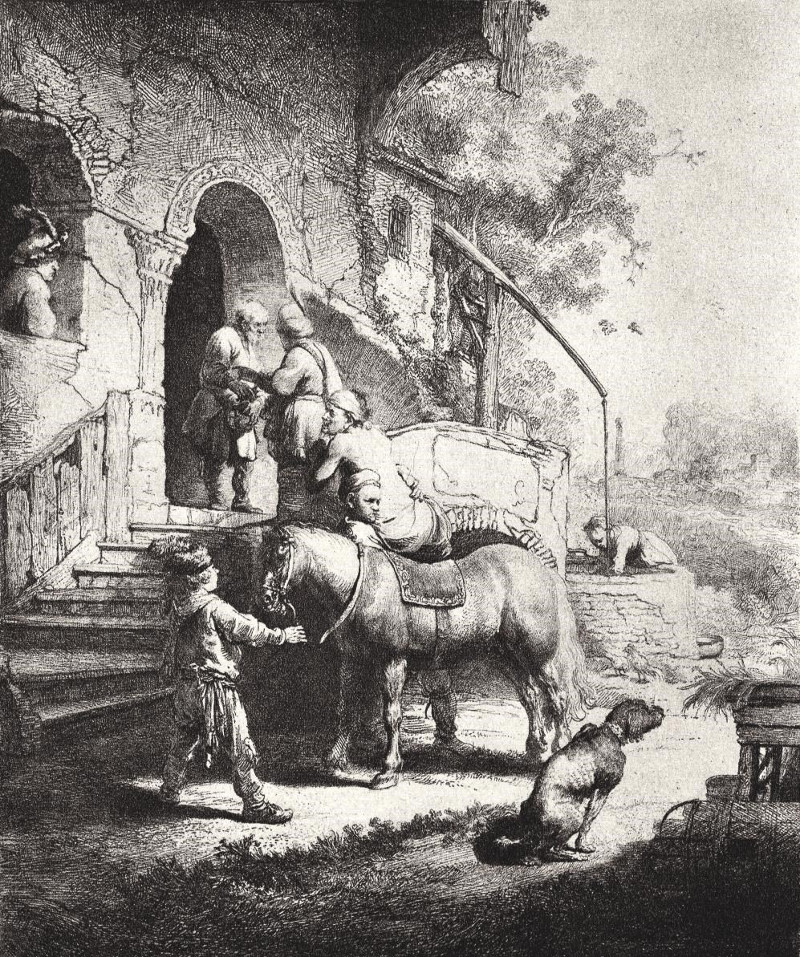

556. The Good Samaritan. (Amsterdam.)

503. Rest on the Flight, 1631. (The Hague.)

504. Old Woman. (London.)

505. Anatomy of Professor Tulp. (The Hague.)

506. Rembrandt and Saskia

Here we have a picture

of Rembrandt and his wife; they are both looking into a mirror:

507. Rembrandt with Saskia on his lap. (Dresden.)

522. Saskia with the red flower. (Dresden.)

508. Oriental with a Turban. (Prague.)

It is interesting to hear

of an experience which Hermann Grimm relates. He introduced the use of

Lantern-slides in University lecturing. It is evident on other occasions,

also, how much can be gained from the use of lantern slides and projectors

in familiarising ourselves with the world of Art. But once when Hermann

Grimm was lecturing on Rembrandt, the slides arrived a little late. He had

not time to go through them beforehand, and saw them for the first time

during the lecture, which thus became a kind of running conversation

with his hearers, among whom there were always older people as well

as students.

Now I need scarcely remind

you that in lecture halls, which are generally well lighted, a more

or less wide-awake attention prevails — occasionally more, generally

less: But the customary condition was changed in as much as the hall

was darkened. And through the darkness and the effect of the Rembrandt

pictures thrown upon the screen, people in the audience again and again

had a peculiar impression, as Hermann Grimm himself relates. In effect,

through the extraordinary vividness which Rembrandt can achieve, one

really has the feeling that such a character is present here, among

the people in the room. He is there — and if you imagined all

the paraphernalia removed — if there were only the light-picture

by itself — it would be all the more vivid. The number of people

in the room is simply increased by one, so vividly does this figure

live among us.

Rembrandt attains this effect

because he places his figures into that element in which man always

lives — though he is unconscious of it — the element of

light and dark. This light and dark which is common to us all, Rembrandt

pours out over his figures, and so places them into this living interplay

of light and darkness, thus endowing them with a common element —

in which the onlooker himself is living. That is the wonderful thing

in Rembrandt.

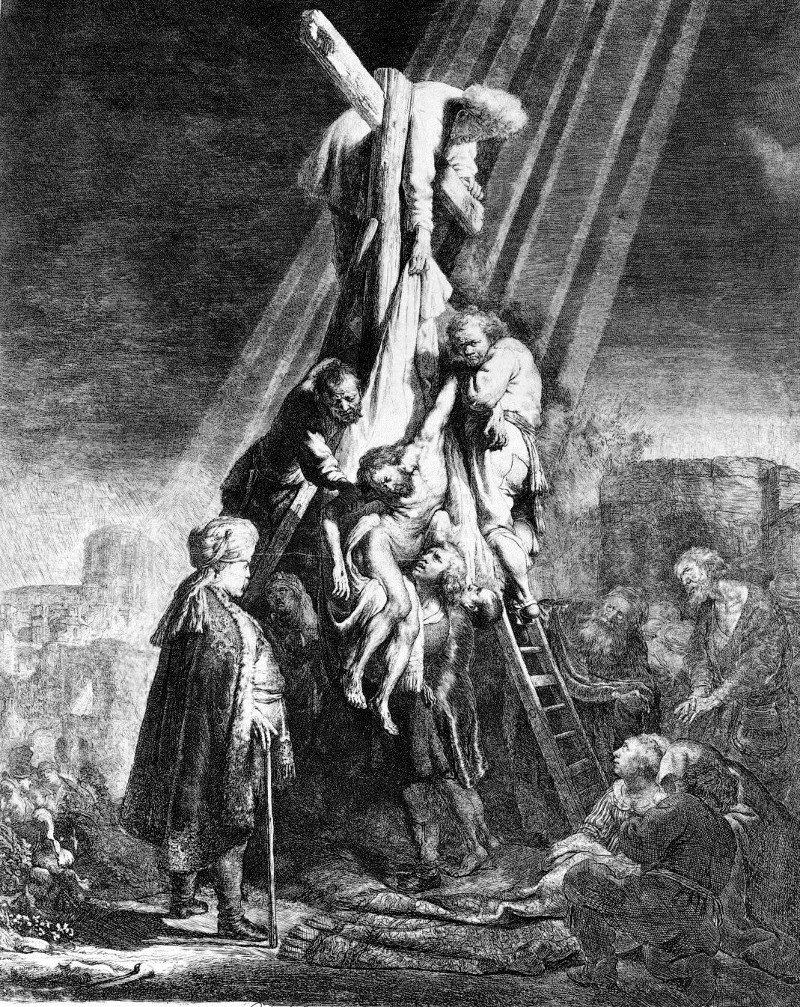

509. Descent from the Cross. (Alte Pinakothek.

Munich.)

Here you see there is a

decided attempt at a composition. Yet the composition, as such, it must

be admitted, is not a great success; at any rate it is by no means equal

to what is called so in the Southern Art. But look at the characteristic

Rembrandt quality once more. Infinite mysteries speak to us out of this

picture, simply through the distribution of the masses of light. The

composition is truly not very great, and yet I think the picture makes

an extraordinary deep impression upon us.

I should really have shown

the next two pictures before this one, but I have purposely chosen the

reverse order. I beg you to compare this picture with the two next,

which most probably preceded this one in time. There is probably an

interval of about two between this picture and the next but one. Showing

the pictures in the reverse order, I wish to illustrate how Rembrandt

perfected himself. He was constantly wrestling and striving. Compare

this picture with the next but one — that of the Ascension —

and you will see how he advanced. Compare them with respect to depth

and inwardness. The next is the Resurrection.

511. The Resurrection. (Munich. Alto Pinakothek.)

512. The Ascension of Christ (Munich. Alto

Pinakothek.)

And now we come to:

510. The Entombment. 1639. (Alte Pinakothek. Munich.)

With the

“Entombment,” which undoubtedly represents a considerable

advance on this, we come near the year 1640 — or, at any rate,

the close of the 1630s.

513. Sermon of John the Baptist. (Berlin.)

514. Abraham's Sacrifice. (Eremitage. St. Petersburg.)

515. Abraham and Three Angels. (Eremitage.

St. Petersburg.)

516. The Archangel Raphael leaving Tobias. (Louvre.

Paris.)

517. The Chaste Susanna.

520. The Wedding of Samson. (Dresden.)

Now for an example of a

landscape by Rembrandt:

518. Landscape with the Good Samaritan.

(Kraków.)

519. Landscape with the Arched Bridge. (Berlin.)

521. The Visitation of Mary (Detroit.)

522. Saskia with the red flower. (Dresden.)

And now we come to some

of the most famous of his pictures:

524. Allegory of the Peace of Westphalia. (Rotterdam.)

525. The Night Watch (Amsterdam.)

The Amsterdam Citizen's

Guard gathered round the drummers in the night — a whole host

of individual figures. Rembrandt was not the only artist of his time

to paint such pictures as this. Only he did so with an unique perfection.

Such a picture shows us especially how this artist is rooted in the

people. Look at this whole collection of men. Some Guild or other —

people of one and the same class or calling, men who belonged together

— ordered the picture jointly; each one paying his share. This

man here, of whom only half the head is visible, made a great fuss.

He was very angry and Rembrandt got into trouble because he did not

find himself portrayed in his full glory.

“The Night Watch”

shows us in the most beautiful way how Rembrandt had progressed. Look

at the wonderful distribution in this picture of the light and darkness.

This is, indeed, the very time of the great deepening of Rembrandt's

life. The picture dates from 1642, the same year that he lost the wife

whom we saw in the portrait just now, and in the portrait of the two

together.

523. The Lady with the Fan. (London.)

526. The Holy Family (Leningrad, Eremitage.)

I think you will feel in

these pictures a greater clarity, a more sublime quality than in the

former ones.

Now we would like to show

a series of “self-portraits”:

530. Self-Portrait, 1645. (Amsterdam.)

531. Self-Portrait, 1656. (Dresden.)

532. Self-Portrait, 1669. (London.)

Then we have an

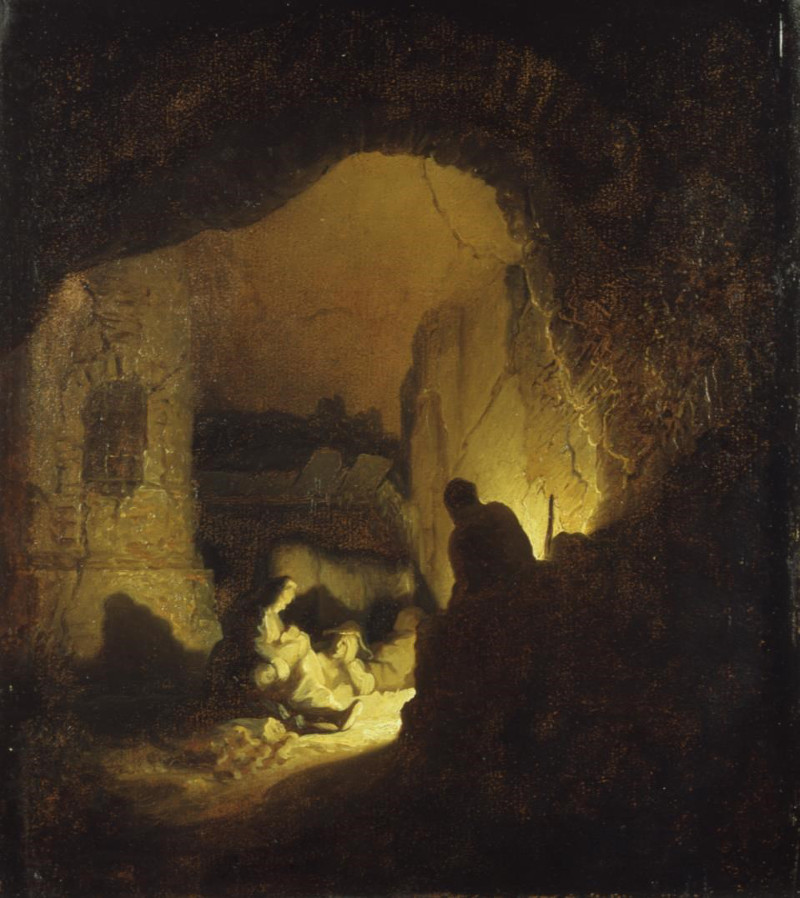

“Adoration”:

527. Adoration of the Shepherds. (Alte Pinakothek.

Munich.)

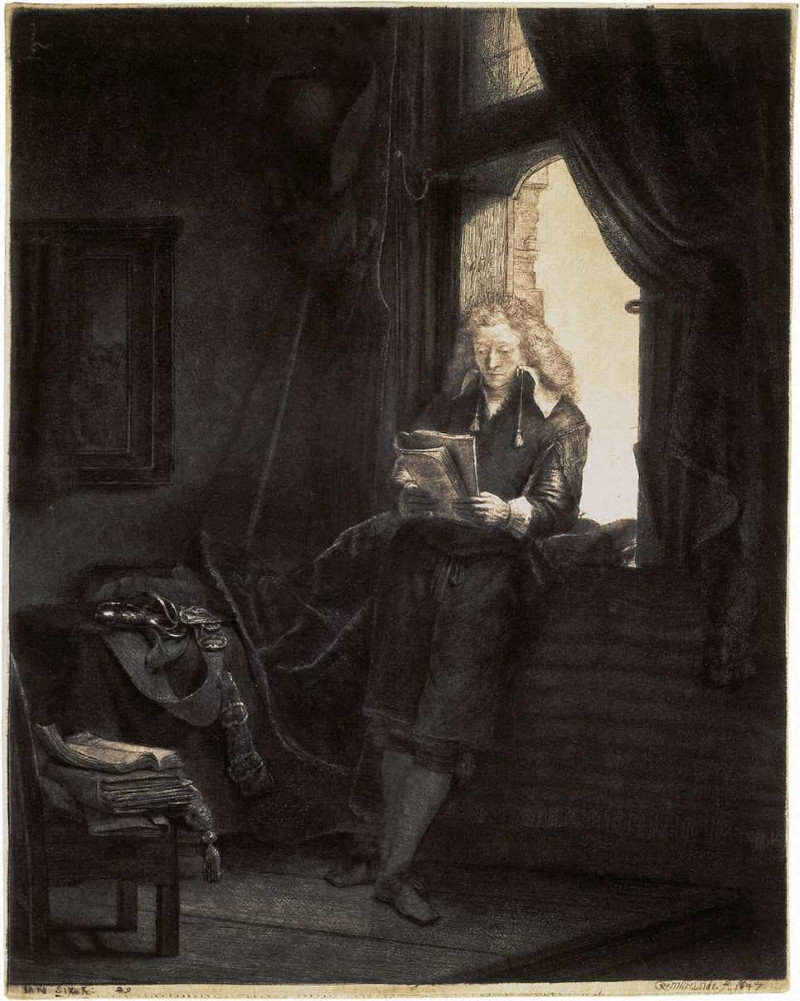

563. The Reader at the Window. (Copenhagen.)

With all its simplicity,

this is surely one of his most characteristic pictures. To show the

reader in the light, the light itself is made of the subject-matter,

as it were — the subject of the story the picture tells.

534. Susanna and the Elders. (Berlin.)

535. Portrait of a Painter (New York.)

536. Christ at Emmaus. (Louvre, Paris.)

A picture of great

tenderness. We have now come to the year 1648.

537. The Vision of Daniel. (Berlin.)

538. Rembrandt's Brother Adrian, 1650. (The Hague.)

539. Christ and the Adulteress. (Minneapolis.)

I may remark that in the vast

majority of Rembrandt's pictures, the Christ is by no means beautiful.

540. Young Woman in Front of a Mirror (Leningrad,

Eremitage.)

And now we come to that

most beautiful picture:

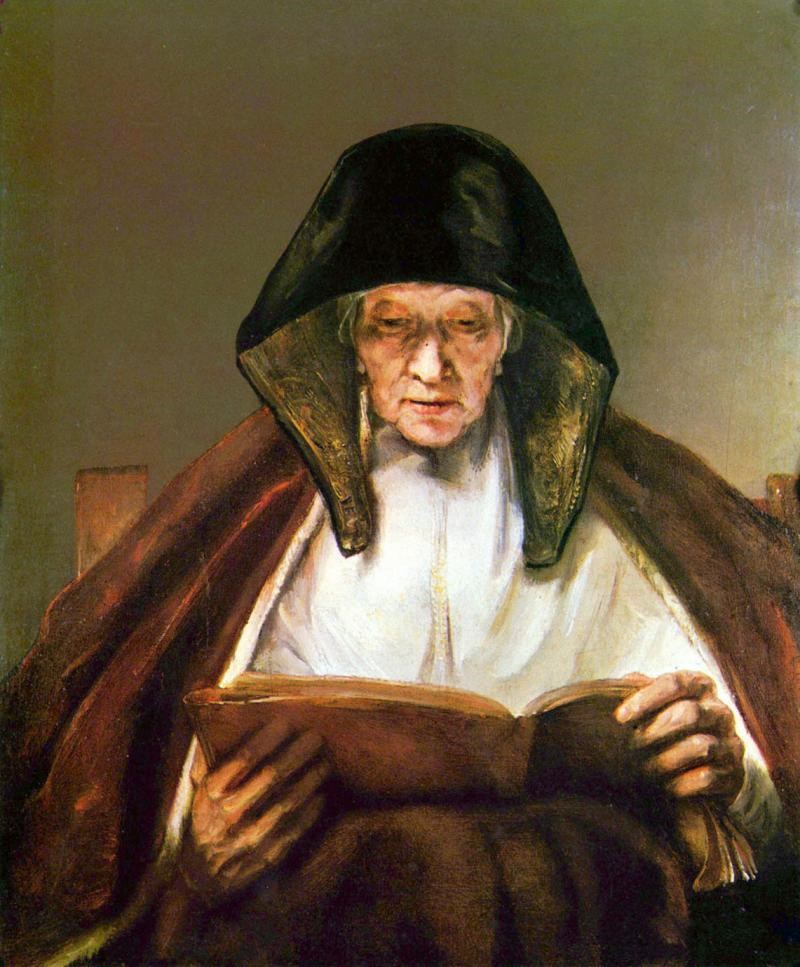

541. An Old Woman Opening a Book to Read. (Paris.)

542. The Warrior in Armour. (Glasgow.)

(Rembrandt School)

543. Rembrandt's Son Titus (London.)

544. The Polish Rider. (New York.)

You would realise what

Rembrandt is if you could see side by side with this picture the picture

of a horse by Rubens, for example. Then you would see the whole difference

in the conception of these two pictures.

544a. Phillip II of Spain on a Horse

by Peter Paul Rubens

This horse is really moving;

it is really a living horse. No horse by Rubens, ever really moves.

Please do not think that this is unconnected with the artist's peculiar

conception out of the element of light. He who aims at what is merely

seen, he who merely tries to reproduce the “reality,” will,

after all, never be able to produce more than the frozen form. However

great his work may be, it will always contain just a little of what

we might describe as a kind of cramp, or paralysis, poured out over

the whole picture.

But the artist who holds fast

the single moment in the weaving, ever-moving element that plays round the

figures — the artist who does not work merely

“realistically,” but places his figures into the true reality

which is the elemental world — he will achieve a real impression of

movement.

545. The Doctor Arnold Tholinx. (Paris.)

546. Jacob blessing Ephraim and Manasseh. (Cassel.)

547. Adoration of the Magi. (Buckingham Palace.)

548. An Old Woman. (Paris.)

Look at this old woman.

Is she not really cutting her nails?

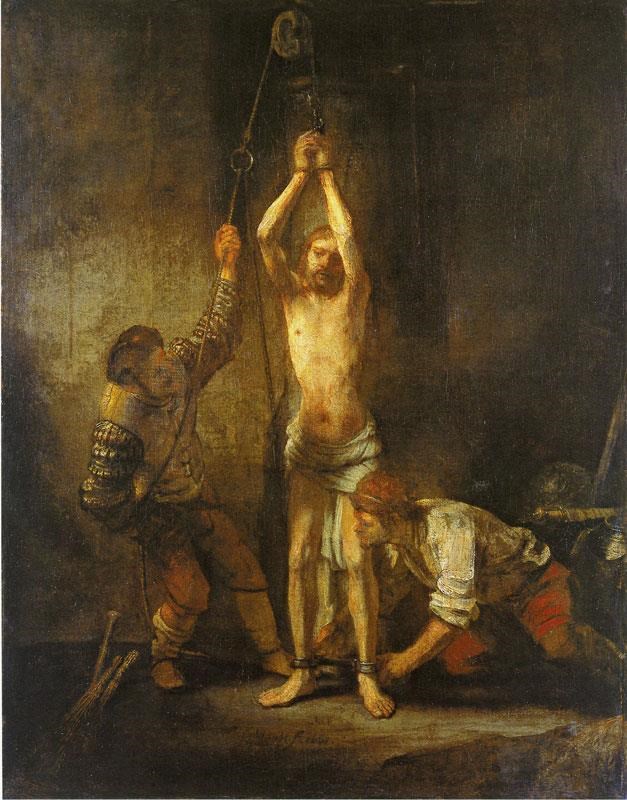

550. The Scourging of Christ. (Darmstadt.)

551. Jakob Wrestling with the Angel, 1659. (Berlin.)

552. The Banquet of Julius Civilis or The leader of

the Batavians against the Romans, 1661. (Stockholm.)

549. The Lady with the Ostrich Feathers.

(Philadelphia.)

553. The Staal-Meisters. (Amsterdam.)

Here, again, we have a picture

painted by special command of these great gentlemen. Yet it is one of

his greatest masterpieces. See the wonderful simplicity with which they

are presented here — the dignitaries of the Guild whose task it

was to test the finished cloth and set their seal upon it as a sign

that it was good. They are the Presidents of a Clothmakers' Guild —

the Stall-Meisters. Of course, they club together to pay for the picture,

but as these were especially high lords and masters, Rembrandt must

see to it that this time no single face is eclipsed. Every face must

come out properly in full relief. And with the high artistic perfection

of this picture this is attained. These gentlemen did not go quite so

far as the Professors of Anatomy with their half-dissected corpse; one

of them holds in his hand a piece of paper on which their names are

recorded.

505. Anatomy of Professor Tulp. (The Hague.)

554. Portrait of an Old Woman. (National Gallery.

London.)

533. Portrait of Himself. (Lord Iveagh's Collection.

London.)

And now the work of a very

old Rembrandt:

555. The Return of the Prodigal. (St. Petersburg.)

And now I wish to show you

the well-known picture of Faust.

564. Dr. Faustus. (An etching.)

When we see this picture,

we are reminded of what I said in one of our last lectures — how

Goethe himself in his “Faust” portrays the figure of the

16th century in this weaving of the light. — But Rembrandt had

revealed it before Goethe.

I must not leave it unsaid

that to know Rembrandt fully it is most necessary to be acquainted with his

art as an etcher. The especial love for this Art is, indeed, characteristic

of that stream to which Rembrandt wished, above all, to devote himself.

He is no less great as an etcher co, than as a painter.

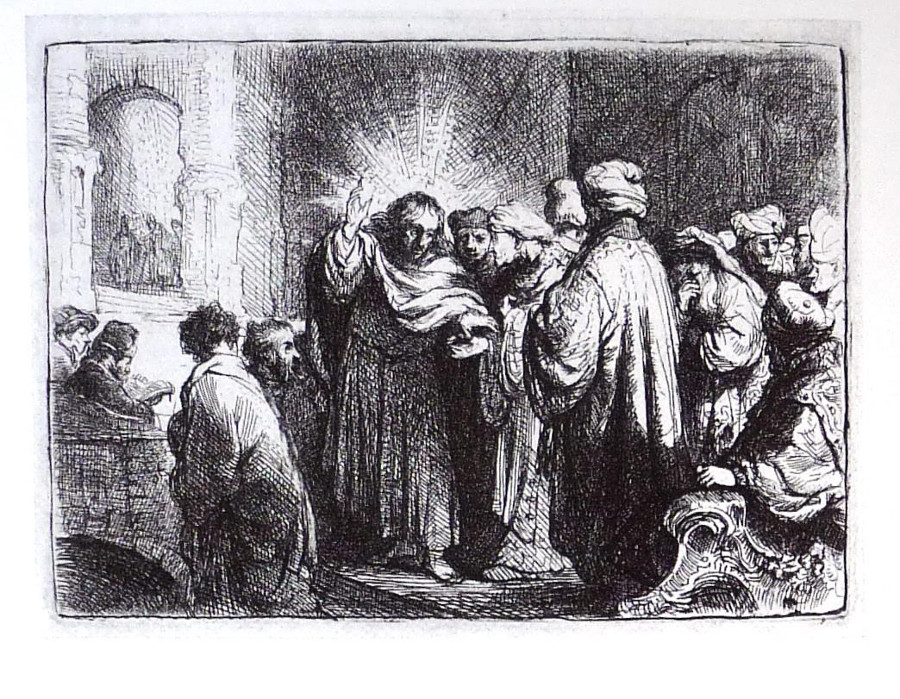

Etchings by Rembrandt:

558. Descent From the Cross

557. Tribute Money

559. Ecce homo

567. Christ of the Mount of Olives

565. Christ Healing the Sick

This is the so-called

Hundred Guilder Print: “Come unto me all you who labor and

are burdened you ...”

We see in it the real beauty

of Rembrandt's art, especially in how these characteristic figures around

the Christ figure are expressed.

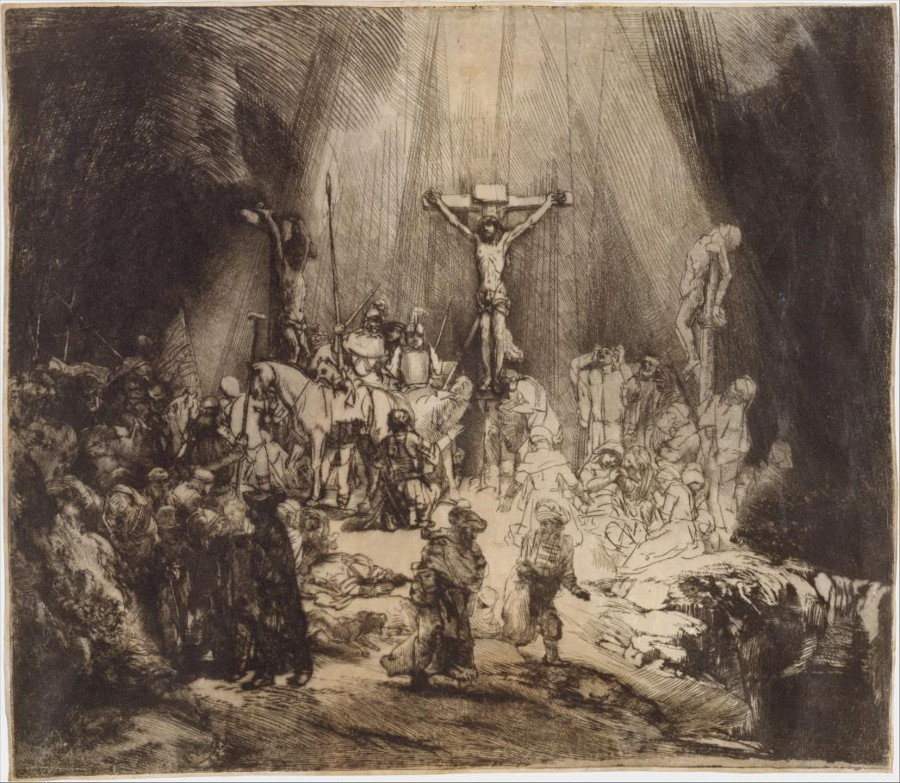

566. The Three Crosses

And now we want to add to

the self-portraits we have shown you as a final scene, another etching:

529. Self-portrait with propped arm, 1639.

How different is Rembrandt

from the other artists whose works we have seen during these lectures:

It was only in Dürer that we saw the first lighting-up of what

appears so wonderfully in Rembrandt. Rembrandt is a unique figure; he

stands alone and isolated. In the continuous study of the history of Art,

it is especially fascinating to dwell upon what is really characteristic

in the creations of single individualities. Rembrandt, above all, makes

us aware of the immediate individual presence of a strong and forceful,

mighty personality, lighting forth in the seventeenth century.

At a time like the present

it is not without importance that we should turn our gaze to an epoch

in which, beside all the devastation that was taking place in Europe,

there was this immediate and original creation out of a human soul —

a human soul of whom we may, indeed, believe that he was connected directly

with the prime sources and elements of world-existence.

I hope it will be given

to us while we can still be here together to show some other aspects

also of the continued development of Art.

|