|

Everything in the drama is presented, therefore, in a

completely individual way. Through this, the truth

portrayed by the particular figures brings out as clearly

as possible the development of the soul of a human being. At

the beginning, Thomasius is shown in the physical world, but

certain soul-happenings are hinted at that provide a wide basis

for such development, particularly an experience at a

somewhat earlier time when he deserted a girl who had been

lovingly devoted to him. Such things do take place, but this

individual happening has a different effect on a man who has

resolved to undertake his own development. There is one deep

truth necessary for him who wants to undergo development:

self-knowledge cannot be achieved by brooding within

oneself but only through diving into the being of others.

Through self- knowledge we must learn that we have emerged from

the cosmos. Only when we give ourselves up can we change into

another Self. First of all, we are transformed into whatever

was close to us in life.

When at first Johannes sinks more deeply into himself and then

plunges in self-knowledge into another person, into the one to

whom he has brought bitter pain, we see this as an example of

the experience of oneself within another, a descent into

self-knowledge. Theoretically, one can say that if we wish to

know the blossom, we must plunge into the blossom, and the best

method of acquiring self-knowledge is to plunge again,

but in a different way, into happenings we once took part in.

As long as we remain in ourselves, we experience only

superficially whatever takes place. In contrast to true

self-knowledge, what we think of other persons is then mere

abstraction.

For

Thomasius at first, what other people have lived through

becomes a part of him. One of them, Capesius, describes some of

his experiences; we can observe that they are rooted in real

life. But Thomasius takes in more. He is listening. His

listening is singular; later, in Scene

Eight, we will be able to characterize it. It is really as if

Thomasius' ordinary Self were not present. Another deeper force

appears, as though Thomasius were creeping into the soul

of Capesius and were taking part in what is happening from

there. That is why it is so absolutely important for Thomasius

to be estranged from himself. Tearing the Self out of oneself

and entering into another is part and parcel of self-knowledge.

It is noteworthy, therefore, that what he has listened to in

Scene One, Thomasius says, reveals:

... A mirrored image of the whole of life,

that showed me clearly to myself.

What is revealed to us out of the spirit

has led me to perceive how many men,

who think themselves a whole, in fact

hear in themselves one single facet only.

In order to unite within myself

all these divergent sides,

I started boldly on the path taught here —

and it has made of me a nothing.

Why

has it made a “nothing” of him? Because through

self-knowledge he has plunged into these other persons.

Brooding in your own inner self makes you proud, conceited.

True self-knowledge leads, first of all, by having to

plunge into a strange Self, into suffering. In Scene One

Johannes follows each person so strongly that when he listens

to Capesius he becomes aware of the words of Felicia within the

other soul. He follows Strader into the loneliness of the

cloister, but at first this has the character of something

theoretical. He cannot reach as far as he is later led, in

Scene Two, through pain. Self-knowledge is deepened by the

meditation within his inner Self. What was shown in Scene One

is shown changed in Scene Two through self-knowledge

intensified from abstraction to a concrete imagination. Those

well-known words, which we have heard through the centuries as

the motif of the Delphic Oracle, bring about a new life for

this man Johannes, though at first it is a life of estrangement

from himself.

Johannes enters, as a knower-of-himself, into all the outer

phenomena. He finds his life in the air and water, in the rocks

and springs, but not in himself. All the words that we can let

sound on stage only from outside are actually the words

of his meditation. As soon as the curtain rises, we have to

confront these words, which would sound louder to anyone

through self-knowledge than we can dare to produce on the

stage. Thereafter, he who is learning to know himself dives

into the other beings and elements and thus learns to know

them. Then in a terrible form the same experience he has had

earlier appears to him.

It

is a deep truth that self-knowledge, when it progresses

in the way we have characterized, leads us to see ourselves

quite differently from the way we ever saw ourselves

before. It teaches us to perceive our “I” as a

strange being.

Man

believes his own outer physical sheath to be the closest thing

to himself. Nowadays, when he cuts a finger, he is much more

connected with the painful finger than when, for instance, a

friend hurts him with an unjust opinion. How much more

does it hurt a modern person to cut his finger than to

hear an unjust opinion! Yet he is only cutting into his bodily

sheath. To feel our body as a tool, however, will come about

only through self- knowledge.

Whenever a person grasps an object, he can feel his hand to

some degree as a tool. This, too, he can learn to feel with one

or another part of his brain. The inward feeling of his brain

as instrument comes about at a certain level of self-knowledge.

Specific places within the brain are localized. If we hammer a

nail, we know we are doing it with a tool. We know that

we are also using as tool one or another part of the brain.

Through the fact that these things are objective and can become

separate and strange to us, we come to know our brain as

something quite separate from us. Self-knowledge requires this

sort of objectivity as regards our body; gradually our outer

sheath becomes as objective to us as the ordinary tools we use.

Then, as soon as we have made a start at feeling our bodily

sheath as separate object, we truly begin to live in the

outside world.

Because a person feels only his body, he is not clear about the

boundary between the air outside and the air in his lungs. All

the same, he will say that it is the same air, outside and

inside. So it is with everything, with the blood, with

everything that belongs to the body. But what belongs to the

body cannot be outside and inside — that is mere

illusion. It is only through the fact that we allow the

internal bodily nature to become outward that in truth it finds

a further life out in the rest of the world and the cosmos.

In

the first scene recited today there was an effort to express

the pain of feeling estranged from oneself — the pain of

feeling estranged because of being outside and within all the

other things. Johannes Thomasius' own bodily sheath seems like

a person outside himself. But just because of that — that

he feels his own body outside — he can see the approach

of another body, that of the young girl he once deserted. It

comes toward him; he has learned how to speak with the very

words of the other being. She says to him, whose Self has

widened out to her:

He brought me bitter sorrow;

I gave him all my trust.

He left me in my grief alone.

He robbed me of the warmth of life

and thrust me deep into cold earth.

Then guilt, very much alive, rises up in the soul when,

plunging our own Self into another and attaching

ourselves to the pain of this other being, the pain is

spoken out. This is a deepening, an intensifying. Johannes is

truly within the pain, because he has caused it. He

feels himself dissolving into it and then waking up

again. What is he actually experiencing?

When we try to put all this together, we will find that the

ordinary, normal human being undergoes something similar only

in the condition we call kamaloka. The initiate, however,

has to experience in this world what the normal person

experiences in the spiritual world. Within the physical body he

must go through what ordinarily is experienced outside the

physical body. All the elements of kamaloka have to be

undergone as the elements of initiation. Just as Johannes

dives into the soul to whom he has brought such grief, so must

the normal human being in kamaloka dive into the souls to which

he has brought pain. It is just as if a slap in the face has to

come back to him; he has to feel the same pain. The only

difference is that the initiate experiences this in the

physical body, and other people after death. The one who goes

through this here will afterward live otherwise in kamaloka.

But even all that one undergoes in kamaloka can be so

experienced that one does not become entirely free. It is a

most difficult task to become completely free. A man

feels as if he were chained to his physical conditions.

In

our time one of the most important elements for our development

— not yet so much in the Greco-Roman epoch but especially

important nowadays — is that the human being must

experience how infinitely difficult it is to become free of

himself. Therefore, a notable initiation experience is

described by Johannes as feeling chained to his own lower

nature; his own being seems to be a creature to which he is

firmly fettered:

I feel the chains

that hold me fettered fast to you.

Prometheus was not chained so fast

upon the cliffs of Caucasus

as I am chained to you.

This belongs to self-knowledge; it is a secret of self-

knowledge. We should try to understand it correctly.

A

question about this secret could be phrased like this: have we

in some way become better human beings by becoming earth

dwellers, by entering into our physical sheaths, or would we be

better by remaining in our inner natures and throwing off those

sheaths? Superficial people, taking a look at life in the

spirit, may well ask: why ever do we have to plunge down into a

physical body? It would be much easier to stay up there and not

get into the whole miserable business of earthly existence.

For

what reason have the wise powers of destiny thrust us down

here? Perhaps it helps our feelings a little to say that for

millions and millions of years the divine, spiritual powers

have worked on the physical body. Because of this, we should

make more out of ourselves than we have the strength to do. Our

inner forces are not enough. We cannot yet be what the gods

have intended for us if we wish to be only what is in our inner

nature, if our outer sheaths do not work some corrections in

us. Life shows us that here on earth man is put into his

physical sheaths and that these have been prepared for him by

the beings of three world epochs. Man has now to develop his

inner nature. Between birth and death, he is bad; in Devachan

he is a better creature, taken up by divine, spiritual beings

who shower him with their own forces. Later on, in the Vulcan

epoch, he will be a perfect being. Now on the earth he is a

being who gives way to this or that desire. Our hearts, for one

thing, are created with such wisdom that they can hold out for

decades against the excesses we indulge in, such as drinking

coffee. What man can be today through his own will is the way

he travels through kamaloka. There he has to learn what he can

be through his own will, and that is certainly nothing very

good. Whenever man is asked to describe himself, he cannot use

the adjective “beautiful.” He has to describe

himself as Johannes does in Scene Two:

Yet how do I behold myself!

My human form is lost;

as raging dragon I must see myself,

begot of lust and greed.

I clearly sense

how an illusion's cloud

has hid from me till now

my own appalling form.

Our

inner nature stretches flexibly within our bodily sheaths and

is hidden from us. When we approach initiation, we learn

really to see ourselves as a kind of raging dragon. Therefore,

these words are drawn up out of the deepest perception; they

are words of self-knowledge, not of self-brooding:

It is myself.

So knowledge chains to you, pernicious monster,

me myself, pernicious monster.

At

bottom, they are both the same, one the subject, the other the

object.

I sought to flee from you.

This

flight, however, merely leads the human being directly to

himself.

But

then the crowd turns up, the crowd we find ourselves in when we

really look into ourselves. We find ourselves to be a

collection of lusts and passions we had not noticed earlier,

because each time we wanted to look into ourselves our eyes

were distracted to the world outside. Indeed, compared to

what we would have seen inside, the world outside is

wonderfully beautiful. Out there, in the illusion, in the maya

of life, we stop looking at ourselves inwardly. When people

around us, however, begin to talk all kinds of stupidity and we

cannot stand it, we escape to where we can be alone. This is

quite important at some levels of development. We can and

should collect ourselves; it is a good means of self-knowledge.

But it can happen that, coming into a crowd of people, we can

no longer be alone; those others appear, either within us or

outside us, no matter; they do not allow us to be alone. Then

comes the experience we must have: solitude actually

brings forth the worst kind of fellowship.

For me, man's final refuge,

for me, my solitude is lost.

Those are genuine experiences. Do not let the strength, the

intensity, of the happenings trouble you. You do not have to

believe that such strength and intensity as described

must necessarily lead to anxiety or fear. It should not prevent

anyone from also plunging into these waters. No one will

experience all this as swiftly or with such vehemence as

Johannes does; it had to come about for him in this way for a

definite purpose, even prematurely, too. A normal

self-development proceeds differently. Therefore, what

occurs in Johannes so tumultuously must be understood as an

individual happening. Because he is this particular individual,

who has suffered a kind of shipwreck, everything he undergoes

takes place much more tempestuously than it otherwise would. He

is confronted by the laws of self-development in such a way

that they throw him completely off balance. As for us, one

thing should be awakened by this description of Johannes, that

is, the perception that true self-knowledge has nothing to do

with trite phrases, that true self- knowledge inevitably leads

us into pain and sorrow.

Things that once were a source of delight can assume a

different face when they appear in the realm of self-

knowledge. We can long for solitude, no doubt, when we have

already found self-knowledge. But in certain moments of

self-development it is solitude we have lost when we look for

it as we did earlier, in moments when we flow out into the

objective world, when in loneliness we have to suffer the

sharpest pain.

Learning to perceive in the right way this outpouring of the

Self into other beings will help us feel what has been put into

the Mystery Drama: a certain artistic element has been

created in which everything is spiritually realistic. One who

thinks realistically — a genuine, artistic,

sensitive realist — undergoes at unrealistic

performances a certain amount of suffering. Even what at

a certain level can provide great satisfaction is at another

level a source of pain. This is due to the path of self-

development. A play by Shakespeare, for instance, an

immense achievement in the physical world, can be an

occasion for artistic pleasure. But a certain moment of

development can arrive when we are no longer satisfied by

Shakespeare because we seem inwardly torn to pieces. We go from

one scene to the next but no longer see the necessity that has

ordered one scene to follow another. We begin to find it

unnatural that a scene follows the one preceding it. Why

unnatural? Because nothing holds two scenes together except the

dramatist Shakespeare and his audience. His scenes follow the

abstract principle of cause and effect but not a concrete

reality. It is characteristic of Shakespeare's drama that

nothing of underlying karma is hinted at; this would tie the

scenes together more closely.

The

Rosicrucian drama grew into a realistic, spiritually

realistic one. It makes huge demands on Johannes Thomasius, who

is constantly on stage without taking part actively or showing

a single important dramatic characteristic. He is the one in

whose soul everything takes place, and what is described is the

development of that soul, the real experience of the soul's

development.

Johannes' soul spins one scene realistically out of the one

before it. Through this we see that realistic and

spiritual do not contradict each other.

Materialistic and spiritual things do not need

each other, and they can contradict each other. But

realistic and spiritual are not opposites; it is

quite possible for spiritual realism to be admired even

by a materialistic person. In regard to artistic principles,

the plays of Shakespeare can be thought of as realistic. You

will understand, however, how far the art that goes hand in

hand with a science of the spirit must finally lead. For the

one who finds his Self out in the cosmos, the whole

cosmos becomes an ego being. We cannot bear then anything

coming toward us that is not related to the ego being.

Art will gradually learn something in this direction; it will

come to the ego principle, because the Christ has brought us

our ego for the first time. In the most various realms will

this ego be alive.

In

still another way can the specific human entity be shown within

the soul and also divided into its various components outside.

If someone asked which person represents Atma, which one

Buddhi, which one Manas? ... if someone in the audience could

exclaim, “O yes, that figure on the stage is the

personification of Manas!” ... it would be a horrible

kind of art, a dreadful kind of art. It is a bad theosophical

habit to try to explain everything like this. One would like to

say, “Poor thing!” of a work of art that has to be

“explained.” If it were to be attempted with

Shakespeare's plays, it would indeed be absurd and

downright wrong.

These habits are the childhood diseases of the

theosophical movement. They will gradually be cured. But

for once at least, it is necessary to point them out. It might

even happen that someone tries to look for the nine members of

the human organization in the Ninth Symphony of

Beethoven!

On

the other hand, it is correct to some extent to say that the

united elements of human nature can be assigned to different

characters. One person has this soul coloring, a second person

another; we can see characters on the stage who present

different sides of the whole unified human being. The people we

encounter in the world usually present one or another

particular trait. As we develop from incarnation to

incarnation, we gradually become a whole. To show this

underlying fact on the stage, our whole life has somehow to be

separated into parts.

In

this Rosicrucian Mystery, we will find that everything

that Maria is supposed to be is dispersed among the other

figures who are around her as companions. They form with her

what might be called an “egoity.” We find special

characteristics of the sentient soul in Philia, of the

intellectual soul in Astrid, of the consciousness soul in Luna.

It was for this reason that their names were chosen. The names

of all the characters and beings were given according to

their natures. In Devachan, Scene Seven, particularly,

where everything is spirit, not only the words but also the

placing of the words is meant to characterize the three figures

of Philia, Astrid, and Luna in their exact relationships. The

speeches at the beginning of Scene Seven are a better

description of sentient soul, intellectual soul, and

consciousness soul than any number of words otherwise could

achieve. Here one can really demonstrate what each soul is. One

can show in an artistic form the relationship of the three

souls by means of the levels at which the figures stand. In the

human being they flow into one another. Separated from each

other, they show themselves clearly: Philia as she places

herself in the cosmos; Astrid as she relates herself to the

elements; Luna as she directs herself into free deed and

self-knowledge. Because they show themselves so clearly in the

Devachan scene, everything in it is alchemy in the purest sense

of the word; all of alchemy is there, if one can gradually

discover it.

Not

only as abstract content is alchemy in the scene but in the

weaving essence of the words. Therefore, you should listen not

merely to what is said, nor indeed only to what each single

character speaks, but particularly to how the soul forces speak

in relation to one another. The sentient soul pushes itself

into the astral body; we can perceive weaving astrality there.

The intellectual soul slips itself into the etheric body; there

we perceive weaving ether being. We can observe how the

consciousness soul pours itself with inner firmness into the

physical body. Soul endeavor that has an effect like light is

contained in Philia's words. In Astrid is contained what

brings about the etheric-objective ability to confront the very

truth of things. Inner resolve connected at first with the

firmness of the physical body is given in Luna. We must begin

to be sensitive to all this. Let us listen to the soul forces

in Scene Seven:

|

Philia

(Sentient soul)

|

I will imbue myself

with clearest essence of the light

from worldwide spaces.

I will breathe in sound-substance,

life-bestowing,

from far ethereal regions,

that you, beloved sister, with your work

may reach your goal.

|

|

Astrid

(Intellectual soul)

|

And I will weave

into the radiant light

the clouding darkness.

I will condense

the life of sound,

that glistening it may ring

and ringing it may glisten,

that you, beloved sister,

may guide the rays of soul.

|

|

Luna

(Consciousness soul)

|

I will enwarm soul-substance

and will make firm life-ether.

They shall condense themselves,

they shall perceive themselves,

and in themselves residing

guard their creative forces,

that you, beloved sister,

within the seeking soul

may quicken certainty of knowledge.

|

I

would like to draw your attention to the words of Philia,

Dass dir, geliebte Schwester,

Das Werk gelingen kann.

(that you, beloved sister,

with your work may reach your goal.)

and

to those of Astrid that carry the connotation of something

heavier, more compact,

Dass du, geliebte Schwester ...

“Dass dir,”

“Dass du,”

and then we have the

“Du”

again in Luna's speech woven together with the still heavier,

weighty

Der suchenden Menschenseele

(within the seeking soul)

There the “u” is woven into its neighboring

consonants, so that it can take on a still firmer compactness.

[In the English translation of The Portal of Initiation

these three sound distinctions could not be kept, except

in the word “soul” at the end of Luna's speech, in

which the (spoken) diphthong possesses a nuance of

“u.”]

These are the things that one can actually characterize.

Please remember, it all depends on the “How.” Let

us compare the words Philia speaks next:

I will entreat the spirits of the worlds

that they, with light of being,

enchant soul feeling,

that they, with tone of words,

charm spirit hearing,

with

the rather different ones of Astrid:

I will guide streams of love

that fill the world with warmth,

into the heart

of him, the consecrated one.

Just

here, where these words are spoken, the inner weaving

essence of the world of Devachan has been achieved.

I

am mentioning all this, because the scenes should make it clear

that when self-knowledge begins to unfold into the outer cosmic

weaving and being, we have to give up everything that is

one-sided. We have to learn, too, to be aware — as we

otherwise do only in a quite superficial, pedestrian way

— of what is at hand at every point of existence.

We become inflexible creatures, we human beings, when we stay

rooted to only one spot in space, believing that our

words can express the truth. But words, limited as they are to

physical sound, are not what best will communicate truth.

I would like to put it like this: we have to become sensitive

to the voice itself. Anything as important as Johannes

Thomasius' path to self-knowledge can be rightfully experienced

— it depends on this — only when he struggles

courageously for that self-knowledge and holds on to it.

When self-knowledge has crushed us, the next stage is to begin

to draw into ourselves, to harbor inwardly what was our outer

experience, learning how closely the cosmos is related to

ourselves (for this comes to us after we understand the nature

of the beings around us); now we must attempt courageously to

live with our understanding. It is only one half of the

matter to dive down like Johannes into a being to whom we have

brought sorrow and have thrust into cold earth. For now, we

have begun to feel differently. We summon up our courage to

make amends for the pain we have caused. Now we can dive

into this new life and speak out of our own nature

differently. This is what confronts us in Scene Nine. In

Scene Two the young girl cried out to Johannes:

He brought me bitter sorrow;

I gave him all my trust.

He left me in my grief alone.

He robbed me of the warmth of life

and thrust me deep into cold earth.

In

Scene Nine, however, after Johannes has undergone what

every path to self-knowledge demands, the same being calls to

him:

O you must find me once again

and ease my suffering.

This is the other side of the coin: first the devastation and

despair, and now the return to equilibrium. The being calls to

him:

O you must find me once again ...

It

could not have been described otherwise, this lifting

into perception of the world, this replenishing of

himself with life experience. True self-knowledge through

perception of the cosmos could only have been described

with the words Johannes uses when he comes to himself. It has

begun, of course, in Scene Two:

For many years these words

of weighty meaning I have heard.

Then — after he has dived down into deep earth, after he

has united himself with it — the power is born in his

soul to let the words arise that express the essence of Scene

Nine:

For three years now I've sought

for power of soul, with wings of courage,

to give these words their truth.

Through them a man who frees himself can conquer

and, conquering himself, can find his freedom.

The

words, “O man, unfold your being!” are in direct

contrast to the words of Scene Two, “O man, know thou

thyself!” There appears to us once and again the very

same scene. It leads the first time downward to:

The world and my own nature

are living in the words:

O man, know thou thyself!

Then afterward it is the opposite; it has changed. The scene

characterizes soul development.

You

have also heard the devastating words:

Maria, are you then aware

through what my soul has fought its way?

. . .

For me, man's final refuge,

for me, my solitude is lost.

But

Scene Nine shows how the being of the girl attains first hope

and then security. That is the turning point. It cannot be

constructed haphazardly; it is actual experience. Through

it we can sense how self-knowledge in a soul like Johannes

Thomasius can ascend into a self- unfolding. We should

perceive, too, how his experience is distributed among many

single persons in whom one characteristic has been formed in

each incarnation.

At

the end of the drama a whole community stands there in the Sun

Temple, like a tableau, and the many together are a single

person. The various characteristics of a human being are

distributed among them all; essentially there is one

person there. A pedant might like to object. “Are

there not too many different members of the whole? Surely nine

or twelve would be the correct number!” But reality does

not always work in such a way as to be in complete agreement

with theory. This way it corresponds more nearly with the truth

than if we had all the single constituents of man's being

marching up in military rank and file.

Let

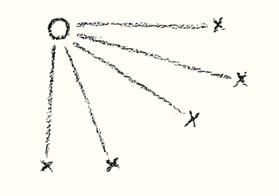

us now put ourselves into the Sun Temple. There are various

persons standing in the places they belong to karmically, just

as their karmas have brought them together in life. But when we

think of Johannes here in the middle and think, too, that all

the other characters are mirrored in his soul, each character

as one of his soul qualities — what is happening there if

we can accept it as reality?

Johannes Thomasius

Karma has actually brought these persons together as in a focal

point. Nothing is without intention, plan, or reason; what the

single individualities have done not only has meaning for each

one himself, but each is also a soul experience for Johannes

Thomasius. Everything is happening twice: once in the

macrocosm, a second time in the microcosm, in the soul of

Johannes. This is his initiation. Just as Maria, for

example, has a special connection with him, so, too, there is

an important part of his soul with a similar connection to

another part of his soul. Those are absolute correspondences,

embodied in the drama uncompromisingly. What one sees as outer

stage- happening is, in Johannes, an inner happening in his

development. There has to come about what the Hierophant has

described in Scene Three:

There forms itself within this circle

a knot out of the threads

which karma spins in world becoming.

It

has already formed itself, and this truly entangled knot shows

what everything is leading toward. There is absolute reality as

to how karma spins its threads; it is not an aimless spinning.

We experience the knot as the initiation event in

Johannes' soul, and the whole scene shows us a certain

individuality actually standing above the others, that is, the

Hierophant, who is directing, who is guiding the threads. We

need only think of the Hierophant's relationship to Maria.

But

it is just there that we can realize how self- knowledge can

illuminate what happens to Maria in Scene Three. It is not at

all pleasant, this emerging out of the Self. It is a thoroughly

real experience, a forsaking of the human sheaths by our inner

power; the sheaths left behind become then a battleground for

inferior powers. When Maria sends down a ray of love to the

Hierophant, it can only be portrayed in this way: down below,

the physical body, taken over by the power of the adversary,

speaks out the antithesis of what is happening above. From

above a ray of love streams down, and below arises a curse.

Those are the contrasting scenes: Scene Seven in

Devachan, where Maria describes what she has actually brought

about, and Scene Three, where, from the deserted body, the

curses of the demonic forces are directed toward the

Hierophant. Those are the two corresponding scenes. They

complete each other. If they had had to be

“constructed” theoretically from the beginning, the

end result would have been incredibly poor.

I

therefore have based today's lecture on one aspect of this

Mystery Drama, and I should like to extend this to

include certain special characteristics that underlie

initiation.

Although it has been necessary to bring out rather sharply what

has just been shown as the actual events of initiation, it

should not let you lose courage or resolve in your own striving

toward the spiritual world. The description of dangers was

aimed at strengthening a person against powerful forces.

The dangers are there; pain and sorrow are the prospect. It

would be a poor sort of effort if we proposed to rise

into higher worlds in the most convenient way. Striving to

reach the spiritual worlds cannot yet be as convenient as

rolling over the miles in a modern train, one of those many

conveniences our materialistic culture has put into our

everyday lives. What has been described should not make us

timid; to a certain extent the very encounter with the

dangers of initiation should steel our courage.

Johannes Thomasius' disposition made him unable to continue

painting; this grew into pain, and the pain grew into

perception. So, it is that everything that arouses pain and

sorrow will transform itself into perception. But we have to

search earnestly for this path, and our search will be possible

only when we realize that the truths of spiritual science

are not at all simple. They are such profound truths for our

whole life that no one will ever understand them perfectly. It

is just the single example in actual life that helps us to

understand the world. One can speak about the conditions of a

spiritual development much more exactly when one describes the

development of Johannes, rather than when one describes the

development of human beings in general. In the book,

Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment,

[Rudolf Steiner, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its

Attainment, Anthroposophic Press, Inc., Spring Valley, NY,

reprinted 1983.] the development that every human being can

undertake is described, simply the concrete possibility as

such. When we portray Johannes Thomasius, we look at a single

individuality. But therewith we lose the opportunity of

describing such development in a general way.

I

hope you will be induced to say that I have not yet spoken out

the essential truth of the matter. For we have described two

extremes and must find the various gradations between

them. I can give only a few suggestive ideas, which should then

begin to live in your hearts and souls.

When I gave you some indications about the Gospel of St.

Matthew, [Rudolf Steiner, The Gospel of St. Matthew,

Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1965.] I asked you not to try to

remember the very words but to try — when you go out into

life — to look into your heart and soul to discover what

the words have become. Read not only the printed

lectures, but read also in a truly earnest way your own

soul.

For

this to happen, however, something must have been given from

outside, something has first to enter into us; otherwise, there

could be self-deception of the soul. If you can begin to read

in your soul, you will notice that what comes to you from

outside re-echoes quite differently within. A true

anthroposophical effort would be first of all to understand

what is said in as many different ways as there are

listeners.

No

one speaking about spiritual science could wish to be

understood in only one sense. He would like to be understood in

as many ways as there are souls present to understand him.

Anthroposophy can tolerate this. One thing is needed, however,

and this is not an incidental remark; one thing is needed:

every single kind of understanding should be correct and

true. Each one may be individual, but it must be true.

Sometimes it seems that the uniqueness of the interpretation

lies in being just the opposite of what has been

said.

When then we speak of self-knowledge, we should realize how

much more useful it is to come to it by looking for mistakes

within ourselves and for the truth outside.

It

shall not be said, “Search within yourself for the

truth!” Indeed, truth is to be found outside ourselves.

We will find it poured out over the world. Through self-

knowledge we must become free of ourselves and undergo those

various gradations of soul experience. Loneliness can become a

horrid companion.

We

can also perceive our terrible weakness when we sense with our

feelings the greatness of the cosmos out of which we have been

born. But then through this we take courage. And we can make

ourselves courageous enough to experience what we perceive.

Then we will finally discover that, after the loss of all the

certainty we had in life, there will blossom for us the first

and last certainty of life, the confidence that finding

ourselves in the cosmos allows us to conquer and find

ourselves anew.

O man, experience the world within yourself!

For then — in striding forth beyond your self —

You will find yourself at last

Within you own true Self.

Let

us feel these words as genuine experience. They will gradually

become for us steps in our development.

|