![[Steiner e.Lib Icon]](https://wn.rudolfsteinerelib.org/icons/pix/rsa_icon2.gif)

|

|

|

Rudolf Steiner e.Lib

|

|

|

The Riddle of Humanity

Rudolf Steiner e.Lib Document

|

|

|

|

The Riddle of Humanity

The Sense-Organs and Aesthetic Experience

A lecture by

Rudolf Steiner

Dornach, August 15, 1916

GA 170

A lecture, hitherto untranslated given at Dornach on August 15, 1916.

Published in The Golden Blade, 1975.

Topics included are: Enlivening the Sense Processes and Ensouling

the Life Processes. Aesthetic Enjoyment and Aesthetic Creativity.

Logic and the Sense for Reality.

It is the ninth of fifteen lectures in the volume

The Riddle of Humanity

In the collected edition of Rudolf Steiner's works, the volume

containing the German texts is entitled,

Das Raetsel des Menschen. Die Geistigen Hintergruende

der Menschlichen Geschichte. Kosmische und

menschliche Geschichte.

(Vol. 170 in the Bibliographic Survey, 1961). The translator is

unknown.

Copyright © 1975

This e.Text edition is provided through the wonderful work of:

The Golden Blade

|

Search

for related titles available for purchase at

Amazon.com!

|

For another version of this lecture, see

The Riddle of Humanity, Ninth Lecture.

| |

THE SENSE-ORGANS

AND AESTHETIC EXPERIENCE

A lecture

given at Dornach,

15 August, 1916

WE have been

concerned with getting to know the human being as he is related to

the world through the realm of his senses and the organs of his

life-processes, and we have attempted to consider some of the

consequences of the fact which underlies such knowledge. Above all,

we have cured ourselves of the trivial attitude which is taken by

many people who like to regard themselves as spiritually minded, when

they think they should despise everything that is called material or

sense-perceptible. For we have seen that here in the physical world

man has been given in his lower organs and his lower activities a

reaction of higher activities and higher connections. The sense of

touch and the Life-sense, as they are now, we have had to regard as

very much tied to the physical, earthly world. The same applies to

the Ego-sense, the Thought-sense and the Speech-sense.

It is different

with the senses which serve the bodily organism only in an internal

way; the sense of Movement, the sense of Balance, the sense of Smell,

the sense of Taste, to a certain extent even the sense of Sight. We

have had to accustom ourselves to regard these senses as a shadowy

reflection of something which becomes great and significant in the

spiritual world, when we have gone through death.

We have

emphasised that through the sense of Movement we move in the

spiritual world among the beings of the several Hierarchies,

according to the attraction or repulsion they exercise upon us,

expressed in the form of the spiritual sympathies and antipathies we

experience after death. The sense of Balance does not only keep us in

physical balance, as it does with the physical body here, but in a

moral balance towards the beings and influences found in the

spiritual world. It is similar with the other senses; the senses of

Taste, Smell and Sight. And just where the hidden spiritual plays

into the physical world, we cannot look to the higher senses for

explanations, but have to turn to those realms of the senses which

are regarded as lower. At the present day it is impossible to speak

about many significant things of this kind, because today prejudices

are so great. Many things that are in a higher spiritual sense

interesting and important have only to be said, and at once they are

misunderstood and in all sorts of ways attacked. For the time being I

have therefore to abstain from pointing out many interesting

processes in the realms of the senses which are responsible for

important facts of life.

In this respect

the situation in ancient times was more favourable, though knowledge

could not be disseminated as it can be today. Aristotle could speak

much more freely about certain truths than is now possible, for such

truths are at once taken in too personal a way and awaken personal

likes and dislikes. You will find in the works of Aristotle, for

example, truths which concern the human being very deeply but could

not be outlined today before a considerable gathering of people. They

are truths of the kind indicated recently when I said: the Greeks

knew more about the connection between the soul and spirit on the one

hand and the physical bodily nature on the other, without becoming

materialistic. In the writings of Aristotle you can find, for

example, very beautiful descriptions of the outer forms of courageous

men, of cowards, of hot-tempered people, of sleepyheads. In a way

that has a certain justification he describes what sort of hair, what

sort of complexion, what kind of wrinkles brave or cowardly men have,

what sort of bodily proportions the sleepyheads have, and so on. Even

these things would cause some difficulties if they were set forth

today, and other things even more. Nowadays, when human beings have

become so personal and really want to let personal feelings cloud

their perception of the truth, one has to speak more in generalities

if one has, under some circumstances, to describe the truth.

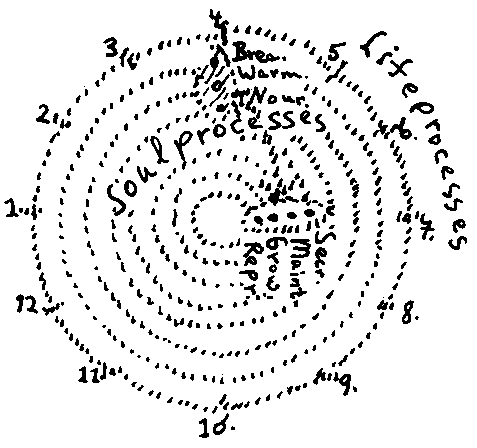

From a certain

point of view, every human quality and activity can be comprehended,

if we ask the right questions about what has been recently described

here. For instance, we have said: the realms of the senses, as they

exist in the human being today, are in a way separate and stationary

regions, as the constellations of the Zodiac are stationary regions

out in cosmic space as compared with the orbiting planets, which make

their journeys and alter their positions relatively quickly. In the

same way, the regions of the senses have definite boundaries, while

the life-processes work through the whole organism, circling through

the regions of the senses and permeating them with the effects of

their work.

Now we have also

said that during the Old Moon period our present sense-organs were

still organs of life, still worked as life-organs, and that our

present life-organs were then more in the realm of the soul. Think of

what has often been emphasised: that there is an atavism in human

life, a kind of return to the habits and peculiarities of what was

once natural; a falling back, in this case into the Old Moon period.

In other words, there can be an atavistic return to the dreamlike,

imaginative way of looking at things that was characteristic of Old

Moon. Such an atavistic falling back into Moon-visions must today be

regarded as pathological.

Please take this

accurately: it is not the visions themselves which are pathological,

for if this were so, and if all that man experienced during the Old

Moon time, when he lived only in such visions, had to be regarded as

pathological — then one would have to say that humanity was ill

during the Old Moon period; that during the Old Moon period man was

in fact out of his mind. That, of course, would be complete nonsense.

What is pathological is not the visions themselves, but that they

occur in the present earthly organisation of the human being in such

a way that they cannot be endured; that they are used by this earthly

organisation in a way that is inappropriate for them as Moon visions.

For if someone has a Moon vision, this is suited only to lead to a

feeling, an activity, a deed which would have been appropriate on the

Old Moon. But if someone has a Moon vision here during the Earth

period and does things as they are done with an earthly organism,

that is pathological. A man acts in that way only because his earthly

organism cannot cope with the vision, is in a sense impregnated by

it.

Take the crudest

example: someone is led to have a vision. Instead of remaining calm

before it, and contemplating it inwardly, he applies it in some way

to the physical world — although it should be applied only to

the spiritual world — and acts accordingly with his body. He

begins to act wildly, because the vision penetrates and stirs his

body in a way it should not do. There you have the crudest example.

The vision should remain within the region to which it naturally

belongs. It does not do so if today, as an atavistic vision, it is

not tolerated by the physical body. If the physical body is too weak

to prevail against the vision, a state of helplessness sets in. If

the physical body is strong enough to prevail, it weakens the vision.

Then it no longer has the character of pretending to be the same as a

thing or process in the sense-world; that is the illusion imposed by

a vision on someone made ill by it. If the physical organism is so

strong that it can fight the tendency of an atavistic vision to lie

about itself, then the person concerned will be strong enough to

relate himself to the world in the same way as during the Old Moon

period, and yet to adapt this behaviour to his present organism.

What does this

mean? It means that the person will to some extent inwardly alter his

Zodiac, with its twelve sense-regions. He will alter it in such a way

that in his Zodiac, with its twelve sense-regions, more

life-processes than sense-processes will occur. Or, to put it better,

the effect is to transform the sense-process in the sense-region into

a life-process and so to raise it out of its present lifeless

condition into life. Thus a man sees, but at the same time something

is living in his seeing; he hears and at the same time something is

living inwardly in his hearing; instead of living only in the stomach

or on the tongue, it lives now in the eye and in the ear. The

sense-processes are brought into movement. Their life is stimulated.

This is quite acceptable. Then something is incorporated in these

sense-organs which today is possessed only to this degree by the

life-organs. The life-organs are imbued with a strong activity of

sympathy and antipathy. Think how much the whole of life depends upon

sympathy and antipathy! One thing is taken, another rejected. These

powers of sympathy and antipathy, normally developed by the

life-organs, are now poured into the sense-organs. The eye not only

sees the colour red; it feels sympathy or antipathy for the colour.

Permeation by life streams hack into the sense organs, so we can say

that the sense-organs become in a certain way life-regions once

more.

The

life-processes, too, then have to be altered. They acquire more

activity of soul than they normally possess for life on earth. It

happens in this way: three life-processes, breathing, warming and

nutrition, are brought together and imbued with heightened activity

of soul. In ordinary breathing we breathe crude material air; with

the ordinary development of warmth it is just warmth, and so on. Now

a kind of symbiosis occurs; when these life-processes form a unity,

when they are imbued with activity of soul, they form a unity. They

are not separate as in the present organism, but set up a kind of

association. An inward community is formed by the processes of

breathing, warming and nutrition; not coarse nutrition, but a process

of nutrition which takes place without it being necessary to eat, and

it does not occur alone, as eating does, but in conjunction with the

other processes.

Similarly, the

other four life-processes are united. Secretion, sustenance, growth

and reproduction are united and also form a process embracing

activity of soul. Then the two parties can themselves unite: not that

all the life-processes then work together, but that, having entered

into separate unities of three and four processes, they work together

in that form.

This leads to

the emergence of soul-powers which have the character of thinking,

feeling and willing; again three. But they are different; not

thinking, feeling and willing as they normally are on earth, but

somewhat different. They are nearer to life-processes, but not as

separate as life-processes are on earth. A very intimate and delicate

process occurs in a man when he is able to endure something like a

thinking back into the Old Moon, not to the extent of having visions,

and yet a form of comprehension arises which has a certain similarity

to them. The sense-regions become life-regions; the life-processes

become soul-processes. A man cannot stay always in that condition, or

he would be unfitted for the earth. He is fitted for the earth

through his senses and his life-organs being normally such as we have

described. But in some cases a man can shape himself in this other

way, and then, if his development tends more towards the will, it

leads to aesthetic creativity; or, if it tends more towards

comprehension, towards perception, it leads to aesthetic experience.

Real aesthetic life in human beings consists in this, that the

sense-organs are brought to life, and the life-processes filled with

soul.

This is a very

important truth about human beings, for it enables us to understand

many things. The stronger life of the sense-organs and the different

life of the sense-realms must be sought in art and the experience of

art. And it is the same with the processes of life; they are

permeated with more activity of soul in the experience of art than in

ordinary life. Because these things are not considered in their

reality in our materialistic time, the significance of the alteration

which goes on in a human being within the realm of art cannot be

properly understood. Nowadays man is regarded more or less as a

definite, finished being; but within certain limits he is variable.

This is shown by a capacity for change such as the one we have now

considered.

What we have

gone into here embraces far-reaching truths. Take one example: it is

those senses best fitted for the physical plane which have to be

transformed most if they are to be led back halfway to the Old Moon

condition. The Ego — sense, the Thought-sense, the immediate

sense of Touch, because they are directly fitted for the earthly

physical world, have to be completely transformed if they are to

serve the human condition which results from this going back halfway

to the Old Moon period.

For example, you

cannot use in art the encounters we have in life with an Ego, or with

the world of thought. At the most, in some arts which are not quite

arts the same relationship to the Ego and to thought can be present

as in ordinary earthly life. To paint the portrait of a man as an

Ego, just as he stands there in immediate reality, is not a work of

art. The artist has to do something with the Ego, go through a

process with it, through which he raises this Ego out of the

specialisation in which it lives today, at the present stage in the

development of the earth; he has to give it a wide general

significance, something typical. The artist does that as a matter of

course.

In the same way

the artist cannot express the world of thought, as it finds

expression in the ordinary earthly world, in an artistic way

immediately; for he would then produce not a poem or any work of art,

but something of a didactic, instructive kind, which could never

really be a work of art. The alterations made by the artist in what

is actually present form a way back towards that reanimation of the

senses I have described.

There is

something else we must consider when we contemplate this

transformation of the senses. The life-processes, I said,

interpenetrate. Just as the planets cover one another, and have a

significance in their mutual relationships, while the constellations

remain stationary, so is it with the regions of the senses if they

pass over into a planetary condition in human life, becoming mobile

and living; then they achieve relationships to one another. Thus

artistic perception is never so confined to the realm of a particular

sense as ordinary earthly perception is. Particular senses enter into

relationships with one another. Let us take the example of

painting.

If we start from

real Spiritual Science, the following result is reached. For ordinary

observation through the senses, the senses of sight, warmth, taste

and smell are separate senses. In painting, a remarkable symbiosis, a

remarkable association of these senses comes about, not in the

external sense-organs themselves, but in what lies behind them, as I

have indicated.

A painter, or

someone who appreciates a painting, does not merely look at its

colours, the red or blue or violet; he really tastes the colours, not

of course with the physical sense-organ — then he would have to

lick it with his tongue. But in everything connected with the sphere

of the tongue a process goes on which has a delicate similarity to

the process of tasting. If you simply look at a green parrot in the

way we grasp things through the senses, it is your eyes that see the

green colour. But if you appreciate a painting, a delicate

imaginative process comes about in the region behind your tongue

which still belongs to the sense of taste, and this accompanies the

process of seeing. Not what happens upon the tongue, but what

follows, more delicate physiological processes — they accompany

the process of seeing, so that the painter really tastes the colour

in a deeper sense in his soul. And the shades of colour are smelt by

him, not with the nose, but with all that goes on deeper in the

organism, more in the soul, with every activity of smelling. These

conjoined sense-activities occur when the realms of the senses pass

over more into processes of life.

If we read a

description which is intended to inform us about the appearance of

something, or what is done with something, we let our speech-sense

work, the word-sense through which we learn about this or that. If we

listen to a poem, and listen in the same way as to something intended

to convey information, we do not understand the poem. The poem is

expressed in such a way that we perceive it through the speech-sense,

but with the speech-sense alone we do not understand it. We have also

to direct towards the poem the ensouled sense of balance and the

ensouled sense of movement; but they must be truly ensouled. Here

again united activities of the sense-organs arise, and the whole

realm of the senses passes over into the realm of life. All this must

be accompanied by life-processes which are ensouled, transformed in

such a way that they participate in the life of the soul, and are not

working only as ordinary life-processes belonging to the physical

world.

If the listener

to a piece of music develops the fourth life-process, secretion, so

far that he begins to sweat, this goes too far; it does not belong to

the aesthetic realm when secretion leads to physical excretion. It

should be a process in the soul, not going as far as physical

excretion; but it should be the same process that underlies physical

excretion. Moreover, secretion should not appear alone. All four

life-processes — secretion, sustenance, growth and reproduction

— should work together, but all in the realm of soul. So do the

life-processes become soul-processes.

On the one hand,

Spiritual Science will have to lead earth-evolution towards the

spiritual world; otherwise, as we have often seen, the downfall of

mankind will come about in the future. On the other hand, Spiritual

Science must renew the capacity to take hold of and comprehend the

physical by means of the spirit. Materialism has brought not only an

inability to find the spiritual, but also an inability to understand

the physical. For the spirit lives in all physical things, and if one

knows nothing of the spirit, one cannot understand the physical.

Think of those who know nothing of the spirit; what do they know of

this, that all the realms of the senses can be transformed in such a

way that they become realms of life, and that the life-processes can

be transformed in such a way that they appear as processes of the

soul? What do present-day physiologists know about these delicate

changes in the human being? Materialism has led gradually to the

abandonment of everything concrete in favour of abstractions, and

gradually these abstractions are abandoned, too. At the beginning of

the nineteenth century people still spoke of vital forces. Naturally,

nothing can be done with such an abstraction, for one understands

something only by going into concrete detail. If one grasps the seven

life-processes fully, one has the reality; and this is what matters

— to get hold of the reality again. The only effect of renewing

such abstractions as elan vital and other frightful

abstractions, which have no meaning but are only admissions of

ignorance, will be to lead mankind — although the opposite may

be intended — into the crudest materialism, because it will be

a mystical materialism. The need for the immediate future of mankind

is for real knowledge, knowledge of the facts which can be drawn only

from the spiritual world. We must make a real advance in the

spiritual comprehension of the world.

Once more we

have to think back to the good Aristotle, who was nearer to the old

vision than modern man. I will remind you of only one thing about old

Aristotle, a peculiar fact. A whole library has been written about

catharsis, by which he wished to describe the underlying purpose of

tragedy. Aristotle says: Tragedy is a connected account of

occurrences in human life by which feelings of fear and compassion

are aroused; but through the arousing of these feelings, and the

course they take, the soul is led to purification, to catharsis. Much

has been written about this in the age of materialism, because the

organ for understanding Aristotle was lacking. The phrase has been

understood only by those who saw that Aristotle in his own way (not,

of course, the way of a modern materialist) means by catharsis a

medical or half-medical term. Because the life-processes become

soul-processes, the aesthetic experience of a tragedy carries right

into the bodily organism those life-processes which normally

accompany fear and compassion. Through tragedy these processes are

purified and at the same time ensouled. In Aristotle's definition of

catharsis the entire ensouling of the life-processes is embraced. If

you read more of his Poetics you will feel in it something

like a breath of this deeper understanding of the aesthetic activity

of man, gained not through a modern way of knowledge, but from the

old traditions of the Mysteries. In reading Aristotle's

Poetics one is seized by immediate life much more than one can

be in reading anything by present day writers on aesthetics, who only

sniff round things and encompass them with dialectics, but never

reach the things themselves.

Later on a

significant high-point in comprehending aesthetic activity of man was

reached in Schiller's Letters on the Aesthetic Education of

Man (1795). It was a time given more to abstractions. Today we

have to add the spiritual to a thinking that remains in the realm of

idealism. But if we look at this more abstract character of the time

of Goethe and Schiller, we can see that the abstractions in

Schiller's Aesthetic Letters embrace something of what has

been said here. With Schiller it seems that the process has been

carried down more into the material, but only because this material

existence requires to be penetrated more deeply by the power of the

spiritual, taken hold of intensively. What does Schiller say? He

says: Man as he lives here on earth has two fundamental impulses, the

impulse of reason and the impulse that comes from nature. Through a

natural necessity the impulse of reason works logically. One is

compelled to think in a particular way; there is no freedom in

thinking. What is the use of speaking of freedom where this necessity

of reason prevails? One is compelled to think that three times three

is not ten, but nine. Logic signifies the absolute necessity of

reason. So, says Schiller, when man accepts the pure necessity of

reason, he submits to spiritual compulsion.

Schiller

contrasts the necessity of reason with the needs of the senses, which

live in everything present in instinct, in emotion. Here, too, man is

not free, but follows natural necessity. Now Schiller looks for the

condition midway between rational necessity and natural necessity.

This middle condition, he finds, emerges when rational necessity bows

before the feelings that lead us to love or not to love something; so

that we no longer follow a rigid logical necessity when we think but

allow our inner impulses to work in shaping our mental images, as in

aesthetic creation. And then natural necessity, on its side, is

transcended. Then it is no longer the needs of the senses which bring

compulsion, for they are ensouled and spiritualised. A man no longer

desires simply what his body desires, for sensuous enjoyment is

spiritualised. Thus rational necessity and natural necessity come

nearer to one another.

You should, of

course, read this in Schiller's Aesthetic Letters themselves;

they are among the most important philosophical works in the

evolution of the world. In Schiller's exposition there lives what we

have just heard here, though with him it takes the form of

metaphysical abstraction. What Schiller calls the liberation of

rational necessity from its rigidity, this is what happens when the

senses are reanimated, when they are led back once more to the

process of life. What Schiller calls the spiritualisation of natural

need — he should really have called it “ensouling”

— this happens where the life-processes work like

soul-processes. Life-processes become more ensouled; sense-processes

become more alive. That is the real procedure, though given a more

abstract conceptual form, that can be traced in Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters. Only thus could he express it at that time,

when there was not yet enough spiritual strength in human thoughts to

reach down into that realm where spirit lives in the way known to the

seer. Here spirit and matter need not be contrasted, for it can be

seen how spirit penetrates all matter everywhere, so that nowhere can

one come upon matter without spirit. Thinking remains mere thinking

because man is not able to make his thoughts strong enough, spiritual

enough, to master matter, to penetrate into matter as it really

is.

Schiller was not

able to recognise that life-processes can work as soul-processes. He

could not go so far as to see that the activity which finds material

expression in nutrition, in the development of warmth and in

breathing, can live enhanced in the soul, so that it ceases to be

material. The material particles vanish away under the power of the

concepts with which the material processes are comprehended. Nor was

Schiller able to get beyond regarding logic as simply a dialectic of

ideas; he could not reach the higher stage of development, attainable

through initiation, where the spiritual is experienced as a process

in its own right, so that it enters as a living force into what

otherwise is merely cognition. Schiller in his Aesthetic

Letters could not quite trust himself to reach the concrete

facts. But through them pulses an adumbration of something that can

be exactly grasped if one tries to lay hold of the living through the

spiritual and the material through the living.

So we see in

every field how evolution as a whole is pressing on towards knowledge

of the spirit. When, at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, a

philosophy was developed more or less out of concepts, longings were

alive in it for a greater concreteness, though this could not yet be

achieved. Because the power to achieve it was inadequate, the

endeavour and the longing for greater concreteness fell into the

crude materialism that has continued from the middle of the

nineteenth century up to the present day. But it must be realised

that spiritual understanding cannot reside only in a turning towards

the spiritual, but must and can overcome the material and recognise

the spirit in matter. As you will see, this has further consequences.

You will see that man as an aesthetic being is raised above earthly

evolution into another world. And this is important. Through his

aesthetic attitude of mind or aesthetic creativity a man no longer

acts in a way that is entirely appropriate for the earth, but raises

the sphere of his being above the sphere of the earth. In this way

through our study of aesthetics we approach some deep mysteries of

existence.

In saying such

things, one may touch the highest truths, and yet sound as if one

were crazy. But life cannot be understood if one retreats faint

heartedly before the real truths. Take a work of art, the Sistine

Madonna, the Venus of Milo — if it is really a work of art, it

does not entirely belong to the earth. It is raised above the events

of earth; that is quite obvious. What sort of power, then, lives in

it — in a Sistine Madonna, in a Venus of Milo? A power, which

is also in man, but which is not entirely fitted for the earth. If

everything in man were fitted only for the earth, he would be unable

to live on any other level of existence as well. He would never go on

to the Jupiter evolution. Not everything is fitted for the earth; and

for occult vision not everything in man is in accord with his

condition as a being of the earth. There are hidden forces which will

one day give man the impetus to develop beyond earth-existence. But

art itself can be understood only if we realise that its task is to

point the way beyond the purely earthly, beyond adaptation to earthly

conditions, to where the reality in the Venus of Milo can be

found.

We can never

acquire a true comprehension of the world unless we first recognise

something which there will be increasing need to recognise as we go

forward to meet the future and its demands.

It is often

thought today that when anyone makes a logical statement that can be

logically proved, the statement must be applicable to life. Logic

alone, however, is not enough. People are always pleased when they

can prove something logically; and we have seen arise in our midst,

as you know, all kinds of world outlooks and philosophical systems,

and no-one familiar with logic will doubt they can all be logically

proved. But nothing is achieved for life by these logical proofs. The

point is that our thinking must be brought into line with reality,

not merely with logic. What is merely logical is not valid —

only what is in keeping with reality.

Let me make this

clear by an example. Imagine a tree-trunk lying there before you, and

you set out to describe it. You can describe it quite correctly, and

you can prove, beyond a doubt, that something real is lying there

because you have described it in exact accordance with external

reality. But in fact you have described an untruth; what you have

described has no real existence. It is a tree-trunk from which the

roots have been cut away, and the boughs and branches lopped off. But

it could have come into existence only along with boughs and blossoms

and roots, and it is nonsense to think of the mere trunk as a

reality. By itself it is no reality; it must be taken together with

its forces of growth, with all the inner forces which enabled it to

come into being. We need to see with certainty that the tree-trunk as

it rests there is a lie; we have a reality before us only when we

look at a tree. Logically it is not necessary to regard a tree-trunk

as a lie, but a sense for reality demands that only the whole tree be

regarded as truth. A crystal is a truth, for it can exist

independently — independently in a certain sense, for of course

everything is relative. A rosebud is not a truth. A crystal is; but a

rosebud is a lie if regarded only as a rosebud.

A lack of this

sense for reality is responsible for many phenomena in the life of

today. Crystallography and, at a stretch, mineralogy are still real

sciences; not so geology. What geology describes is as much an

abstraction as the tree-trunk. The so-called “earth's

crust” includes everything that grows up out of it, and without

that it is unthinkable. We must have philosophers who allow

themselves to think abstractly only in so far as they know what they

are doing. To think in accordance with reality, and not merely in

accordance with logic — that is what we shall have to learn to

do, more and more. It will change for us the whole aspect of

evolution and history. Seen from the standpoint of reality, what is

the Venus of Milo, for instance, or the Sistine Madonna? From the

point of view of the earth such works of art are lies; they are no

reality. Take them just as they are and you will never come to the

truth of them. You have to be carried away from the earth if you are

to see any fine work of art in its reality. You have to stand before

it with a soul attuned quite differently from your state of mind when

you are concerned with earthly things. The work of art that has here

no reality will then transport you into the realm where it has

reality — the elemental world. We can stand before the Venus of

Milo in a way that accords with reality only if we have the power to

wrest ourselves free from mere sense-perception.

I have no wish

to pursue teleology in a futile sense. We will therefore not speak of

the purpose of Art; that would be pedantic, philistine. But what

comes out of Art, how it arises in life — these are questions

that can be asked and answered. There is no time today for a complete

answer, only for a brief indication. It will be helpful if we

consider first the opposite question: What would happen if there were

no Art in the world? All the forces which flow into Art, and the

enjoyment of Art, would then be diverted into living out of harmony

with reality. Eliminate Art from human evolution and you would have

in its place as much untruth as previously there had been Art.

It is just here,

in connection with Art, that we encounter a dangerous situation which

is always present at the Threshold of the spiritual world. Listen to

what comes from beyond the Threshold and you will hear that

everything has two sides! If a man has a sense of reality, he will

come through aesthetic comprehension to a higher truth; but if he

lacks this sense of reality he can be led precisely by aesthetic

comprehension of the world into untruth. There is always this forking

of the road, and to grasp this is very important: it applies not only

to occultism but to Art. To comprehend the world in accordance with

reality will be an accompaniment of the spiritual life that Spiritual

Science has to bring about. Materialism has brought about the exact

opposite — a thinking that is not in accord with reality.

Contradictory as

this may sound, it is so only for those who judge the world according

to their own picture of it, and not in accordance with reality. We

are living at a stage of evolution when the faculty for grasping even

ordinary facts of the physical world is steadily diminishing, and

this is a direct result of materialism. In this connection some

interesting experiments have been made. They proceed from

materialistic thinking; but, as in many other cases, the outcome of

materialistic thinking can work to the benefit of the human faculties

that are needed for developing a spiritual outlook. The following is

one of the many experiments that have been made.

A complete scene

was thought out in advance and agreed upon. Someone was to give a

lecture, and during it he was to say something that would be felt as

a direct insult by a certain man in the audience. This man was to

spring from his seat, and a scuffle was to ensue. During the scuffle

the insulted man was to thrust his hand into his pocket and draw out

a revolver — and the scene was to go on developing from

there.

Picture it for

yourselves — a whole prearranged programme carried out in every

detail! Thirty persons were invited to be the audience. They were no

ordinary people: they were law students well advanced in their

studies, or lawyers who had already graduated. These thirty witnessed

the whole affair and were afterwards asked to describe what had

occurred. Those who were in the secret had drawn up a protocol which

showed that everything had taken place exactly as planned.

The thirty were

no fools, but well-educated people whose task later on would be to go

out into the world and investigate how scuffles and scrimmages and

many other things come about. Of the thirty, twenty-six gave a

completely false account of what they had seen, and only four were

even approximately correct ... only four!

For years

experiments like this have been made for the purpose of demonstrating

how little weight can be attached to depositions given before a court

of justice. The twenty-six were all present; they could all say:

“I saw it with my own eyes.” People do not in the least

realise how much is required in order to set forth correctly a series

of events that has taken place before their very eyes.

The art of

forming a true picture of something that takes place in our presence

needs to be cultivated. If there is no feeling of responsibility

towards a sense-perceptible fact, the moral responsibility which is

necessary for grasping spiritual facts can never be attained. In our

present world, with its stamp of materialism, what feeling is there

for the seriousness of the fact that among thirty descriptions by

eyewitnesses of an event, twenty-six were completely false, and four

only could be rated as barely correct? If you pause to consider such

a thing, you will see how tremendously important for ordinary life

the fruits of a spiritual outlook can become.

Perhaps you will

ask: Were things different in earlier times? Yes, in those times men

had not developed the kind of thinking we have today. The Greeks were

not possessed of the purely abstract thinking we have, and need to

have, in order that we may find our place in the world in the right

way for our time. But here were are concerned not with ways of

thinking, but with truth.

Aristotle tried,

in his own way, to express an aesthetic understanding of life in much

more concrete concepts. And in the earliest Greek times it was

expressed, still more concretely, in Imaginations that came from the

Mysteries. Instead of concepts, the men of those ancient times had

pictures. They would say: Once upon a time lived Uranus. And in

Uranus they saw all that man takes in through his head, through the

forces which now work out through the senses into the external world.

Uranus — all twelve senses — was wounded; drops of blood

fell into Maya, into the ocean, and foam spurted up. Here we must

think of the senses, when they were more living, sending down into

the ocean of life something which rises up like foam from the pulsing

of the blood through life-processes which have now become processes

in the soul.

All this may be

compared with the Greek Imagination of Aphrodite, Aphrogenea, the

goddess of beauty rising from the foam that sprang from the

blood-drops of the wounded Uranus. In the older form of the myth,

where Aphrodite is a daughter of Uranus and the ocean, born from the

foam that rises from the blood-drops of Uranus, we have an

imaginative rendering of the aesthetic situation of mankind, and

indeed a thought of great significance for human evolution at

large.

We need to

connect a further idea with this older form of the myth, where

Aphrodite is the child not of Zeus and Dione, but of Uranus and the

ocean. We need to add to it another Imagination which enters still

more deeply into reality, reaching not merely into the elemental

world but right down into physical reality. Beside the myth of

Aphrodite, the myth of the origin of beauty among mankind, we must

set the great truth of the entry into humanity of primal goodness,

the Spirit showering down into Maya-Maria, even as the blood-drops of

Uranus ran down into the ocean, which also is Maya. Then will appear

in its beauty the dawn of the unending reign of the good and of

knowledge of the good; the truly good, the spiritual. This is what

Schiller had in mind when he wrote, referring especially to moral

knowledge:

Nur durch das

Morgentor des Schoenen

Dringst du in der Erkenntnis Land.*

* Only through the dawn of beauty canst thou

penetrate into the land of knowledge.

You see how many

tasks for Spiritual Science are mounting up. And they are not merely

theoretical tasks; they are tasks of life.

|

Last Modified: 04-May-2025

|

The Rudolf Steiner e.Lib is maintained by:

The e.Librarian:

elibrarian@elib.com

|

|

|

![[Spacing]](https://wn.rudolfsteinerelib.org/AIcons/images/space_72.gif)

|

|