Lecture I

Cimabue, Giotto, and Other Italian Masters

Cimabue,

Giotto,

Andrea da Firenze,

Masolino,

Filippino Lippi,

Masaccio,

Ghirlandajo,

Signorelli,

Mantegna,

Fra Angelico,

Botticelli,

Leonardo da Vinci,

Perugino,

Raphael,

Orcagna,

Francesco Traini.

Dornach, October 8, 1916

My dear Friends,

We shall show a

series of lantern slides representing a period of Art to the

study of which we may presume the human mind will ever and again

return. For in the artistic evolution of this period we witness

the unfolding of some of the deepest human relationships which

the outward course of history reveals in any epoch —

provided we perceive in history the outward picture of inner

spiritual impulses.

First you will see

some picture by Cimabue. Under this name there go, or, rather,

used to go — a number of pictures, church paintings,

springing from a conception of life altogether remote from our

own. Cimabue (or those who worked in the spirit of the school

that is named after him) — Cimabue was working at about the

time, let us say, of Dante's birth. For external history, what

lies before this period in artistic evolution is veiled pretty

much in darkness. So far as anything outwardly preserved is

concerned, the work of Cimabue emerges in such a way that to

begin with in the West, we can find no immediate historic

predecessor. Not only so, but as you will presently bear witness

for yourselves, in the history of European Art the school of

Cimabue remained without succession.

As we try to feel

our way into what comes before us in Cimabue's work, we find

ourselves directed to influences coming over from the East. I

will try to cut a long story short, albeit this will inevitably

involve all the inaccuracies which are unavoidable in such a

brief description. We must not forget that the time of the origin

of Christianity, and the following centuries until the beginning

of the second millennium A.D. when Cimabue lived, — that

this epoch, when Christianity was slowly finding its way into all

spheres of human life and action, was characterised by a turning

of man's spiritual faculties towards the Cosmic, the Spiritual

that transcends the Earth. To a great extent, all man's thought

and interest was directed to the question: How did the higher

spiritual Powers break through into this earthly life? What was

it that came into this earthly world from spheres beyond? Men

wanted to gain a conception of these things. And if one desired

to express in pictorial Art what was thus living in the souls of

men, it could be no question of copying Nature directly in any

sense, or of painting true to Nature, or following this or that

artistic ideal. Rather was it a question of calling forth those

forces in the human soul — those powers of imagination,

among other things — which can, as it were, make visible to

eyes of sense the things from beyond this Earth. Now Western

humanity did not possess sufficient powers of imagination to

bring forth really plastic works of art. We know from earlier

lectures that the Romans were an unimaginative people. It was

into the unimaginative Roman culture that Christianity, coming

from the East, first had to spread. Nevertheless, Christianity as

it came over brought with it, along with all the other

fertilising influences from the East, the fruits of Oriental

imagination. Thus, inner spiritual visions and imaginations were

connected with the early Christian conceptions.

Yonder in Greece

vivid ideas arose, as to how one should portray the figures that

are connected with the Mystery of Golgotha and with its workings.

Witness the evolution of the forms in which they represented the

person of the Redeemer Himself, or the Madonna, the angelic

worlds beyond the Earth, the figures of saints and apostles

transposed into higher realms. We can see quite clearly how, as

Christianity found its way into the West, the Roman

unimaginativeness, if I may so describe it, took hold of what

came over, so rich in fancy and imagination, from the East. In

the very earliest times of Christian Art we find the figure of

Christ Jesus and the others around Him permeated still by the

rich imagination of the Greeks. We find the Redeemer Himself

portrayed in some instances with truly Apollonian features.

Moreover, we know of a remarkable controversy that arose in the

first Christian centuries. Should the Redeemer be represented in

an ugly form, yet so, that through the ugly features there shone

the inner life of soul, the mighty event that was being enacted

in Him for mankind? This type of the Saviour, and similar types

for the other characters connected with the Mystery of Golgotha,

were evolved more in the East of Europe and in Greece. While in

the West, in Italy, men were more of the opinion that the Saviour

and all that were connected with Him should be represented

beautifully. Strangely enough, this discussion went on into the

time when in the West, under the influence of Rome, men had

already lost the faculty to represent real beauty — a

faculty which they had still possessed in former centuries under

the more immediate influence of Greece. For outwardly though

Greece was overcome, in a spiritual sense Rome herself had been

conquered by the Grecian culture, which, however, subsequently

fell into decay amid the unimaginative Romans. Thus in the

succeeding centuries they lost the power to create true plastic

beauty.

Thus there came

over from Eastern tradition the earliest representations,

created, of course, by human imagination, in the effort to

express the new world-impulses springing from the Mystery of

Golgotha. Enriched by Oriental fancy, this early Christian art

was transplanted into Italy. And now, — almost all the

earlier work having been lost, — in Cimabue's paintings or

in those that go by his name, we see what had become of these

impulses by the time of Dante's birth. We see them, as it were,

at a final culminating point. Cimabue's paintings are frescoes on

a large scale and must be understood as such. The figures they

portray appear before us in an altogether unnaturalistic form,

their outlines conceived more out of the life of feeling —

spread over great surfaces, conceived, as it were, in two

dimensions — large surfaces covered with the most eloquent

painting. Alas, it is no longer really visible today, not even

where Cimabue's own works are before us, for his pictures were

for the most part subsequently painted over. The full vividness

of his colouring, with its wonderful two-dimensional conception,

is probably no longer to be seen at any place. Hence Cimabue's

pictures lose least of all when shown in lantern slides. We

recognise their character as a whole; these remarkable figures

— their outlines, as I said, inspired more out of the

feeling-life; colossal figures, conceived at any rate on a

colossal scale and with impressive grandeur, so that one would

say: From other worlds they gaze into this earthly world; they do

not seem to have arisen from this earthly world at all. Such are

his pictures of the Madonna. Such, gazing down into this earthly

world, are his representations of the Saviour and of saints and

angels and the like. We must realise that all these paintings are

born of an imagination, in the background of which was still a

life of spiritual vision. Such vision knew full well that the

impulses of Christianity had come to Earth from another world,

and that this unearthly world could not be represented in mere

naturalistic forms.

We will now show

some of Cimabue's pictures. His works are mostly to be seen in

the Lower Church at Assisi; also in Paris and in Florence. We can

only reproduce a very few:

1. Cimabue: Madonna with Angels and Prophets. (Academy,

Florence.)

Look how the human

eye, for instance, is drawn so that you can clearly see: It is

not copied, but done by following with inner feeling the forces

which were believed to be at work, moulding the eye organically

in the body. The inner activity of the eye is feelingly traced

out, — this is what inspires the forms. Plastically

conceived, it is projected in the spirit on to the flat surface.

In the background, as you can still see by these pictures, is the

conception (far more familiar in the Orient than in the West) of

something working in with abundant power from distant worlds.

When in that time men let these pictures with their golden

background work upon them, they had the feeling of a mighty

overwhelming force pouring in from distant worlds into mankind.

It was as though all the human confusion upon Earth was only

there to be illumined by the Impulses proceeding from a reality

beyond, which was pictured in this way.

2. Cimabue: Madonna (Detail)

Once more a

picture of the Madonna. This, then, is what we have of

Cimabue.

3. Cimabue: Madonna Rucellai. (Santa Maria Novella,

Florence.)

We now pass on to

the study of an artist who, for the external history of art, is,

in a sense, Cimabue's successor. The legend has it that Cimabue

found Giotto as a shepherd-lad who used to draw on rocks and

stones, with the most primitive materials, the animals and other

creatures which he saw around him in the fields. Cimabue,

recognising the great talents of the boy, took him from his

father and trained him in painting. Such legends are often truer

than the outward ‘historic’ truth. It is true, as the

legend suggests, that Giotto — Cimabue's great follower in

the further development of art — was inspired in his inner

life by the whole world in which he found himself through all

that had been created by those whom we include under Cimabue's

name. It is true, indeed, that a whole world of things from

beyond the Earth looked down upon Giotto from the walls around

him. (All this is no longer extant, for reasons we shall

afterwards discuss.) On the other hand, we must never forget that

with Giotto an entirely new artistic world-conception arose in

the West. Indeed, it is Giotto, above all, who in the realms of

art represents the rise of the new age, the 5th post-Atlantean

age. In painting, the 4th post-Atlantean age goes down with

Cimabue; the 5th begins with Giotto. (I leave out of account

whether all the works which a well-founded tradition ascribes to

Giotto were actually painted by him; for that is not the main

point. It is true that under Giotto's name many works are

included of which we can but say that they are painted in his

spirit. Here, however, I will not go into this question, but

simply ascribe to Giotto what tradition has ascribed to him.)

What was mankind

entering into during that time, when we find Dante and Giotto

side by side on the scene of history? It was entering into what I

have always described as the fundamental characteristic of the

5th Post-Atlantean period: into a life in the midst of

earthly-material realities. This must not be taken as a hostile

criticism of Materialism. The time had to come to mankind to

enter fully into the material reality, taking leave for a time of

those things to which they had hitherto looked up and whose light

we find reflected still in Cimabue's paintings.

We may ask

ourselves this question: Who was the first really genuine

materialist? Who was it gave the very first impetus to

materialism? Considering the matter from a somewhat higher point

of view, we shall arrive at an answer which will, of course,

sound paradoxical to modern ears. Nevertheless, for a deeper

conception of human history it is fully justified. I mean that

the first man to introduce the material way of feeling into the

soul-life of mankind was St. Francis of Assisi. I admit it is a

paradox to describe the holy man of Assisi as the first great

materialist, and yet it is so. For one may truly say: the last

great conceptions in which the evolution of mankind is still

described from a standpoint beyond the Earth come before us in

the Divina Commedia of Dante. Dante's great work is to be

regarded as a last expression of a consciousness still directed

more to the things beyond the Earth. On the other hand the vision

of the soul turned to the Earth, the sympathy with earthly

things, comes forth with all intensity in Francis of Assisi, who,

as you know, was before Dante's time. Such things always appear

in the soul-life of mankind a little earlier than their

expression in the realm of art. Hence we see the same impulses

and tendencies which seized the artistic imagination of Giotto at

a later time, living already in the soul of Francis of Assisi.

Giotto lived from 1266 to 1337. Francis of Assisi was a man who

came forth entirely from that kind of outer world which Roman

civilisation, under manifold influences, had gradually brought

forth. To begin with, his whole attention was turned to outer

things. He delighted in the splendour of external riches; he had

enjoyment in all things that make life pleasant, or that enhance

man's personal well being. Then suddenly, through his own

personal experiences his inner life was revolutionised. It was at

first a physical illness which turned him altogether away from

his absorption in external things and turned him to the inner

life. From a man who in his youth was altogether addicted to

external comfort, splendour, reputation, we see him change to a

life of feeling directed purely to the inward things of the soul.

Yet all this took place in a peculiar and unique way. For Francis

of Assisi became the first among those great figures who, from

that time onwards, turned the soul's attention quite away from

all that sprang from the old visionary life. He, rather, turned

his gaze to that which lives and moves immediately upon the

Earth, and above all to man himself. He seeks to discover what

can be experienced in the human soul, in the human being as a

whole, when we see him placed alone, entirely upon his own

resources. St. Francis was surrounded by mighty world-events

which also took their course on Earth, if I may put it so, in

such a way as to sweep past the single life of man, even as the

rich imaginations of an earlier Art had represented sublime

Beings gazing down from beyond the Earth into this world of human

feeling. For in his youth, and later, too, St. Francis was

surrounded by the world-historic conflict of the Guelphs and

Ghibellines. Here one might say there was a battling in greater

spheres, for impulses transcending what the single man on Earth

feels and experiences — impulses for which the human being

on the Earth were but the great and herd-like mass. Right in the

midst of all this life, St. Francis with his ever more numerous

companions upholds the right of the single human individuality,

with all that the inner life of man can experience in connection

with the deeper powers that ensoul and radiate and sparkle

through each human soul. His vision is directed away from

all-embracing cosmic, spiritual spheres, directed to the

individual and human life on Earth. Sympathy, compassion, a life

in fellowship with every human soul, an interest in the

experiences of every single man, a looking away from the golden

background whose splendour, inspired by oriental fancy, had

radiated in an earlier art from the higher realms on to the

Earth. St. Francis and his followers, looking away from all these

things, turned their attention to the joys and sufferings of the

poor man on Earth. Every single man now becomes the main concern,

every single man a world in himself. Yes, one desires to live in

such a way that every single man becomes a world. The Eternal,

the Infinite, the Immortal shall now arise within the breast of

man himself, no longer hovering like the vast and distant sphere

above the Earth.

Cimabue's pictures

are as though seen out of the clouds. It is as though his figures

were coming from the clouds towards the Earth. And so, indeed,

man had felt and conceived the Spiritual World hitherto. We today

have no idea how intensely men had lived with these transcendent

things. Hence, as a rule, we do not realise how immense a change

it was in feeling when St. Francis of Assisi turned the life of

the West more inward. His soul wanted to live in sympathy with

all that the poor man was; wanted to feel the human being

especially in poverty, weighed down by no possessions, and,

therefore, valued by nothing else than what he simply is as a

man. Such was St. Francis of Assisi; and this was how he sought

to feel not only man but Christ Himself. He wanted to feel what

Christ is for poor simple men. Out of the very heart of a

Christianity thus felt, he then evolved his wondrous feeling for

Nature. Everything on Earth became his brother and his sister; he

entered lovingly not only into the human heart but into all

creatures. Truly, in this respect St. Francis is a realist, a

naturalist. The birds are his brothers and his sisters; the

stars, the sun, the moon, the little worm that crawls over the

Earth — all are his brothers and his sisters; on all of

them he looks with loving sympathy and understanding. Going along

his way he picks up the little worm and puts it on one side so as

not to tread it underfoot. He looks up with admiration to the

lark, calling her his sister. An infinite inwardness, a life of

thought unthinkable in former times, comes forth in Francis of

Assisi. All this is far more characteristic of St. Francis than

the external things that are so often written about his life.

So we might say,

man's gaze is now made inward and centered upon the earthly life;

and the influence of this extends, by and by, to the artistic

feeling. For the last time, we might say, Dante in his great poem

represents the life of man in the midst of mighty Powers from

beyond the Earth; but Giotto, his contemporary and probably his

friend, Giotto in his paintings already brings to expression the

immediate interest in all that lives and moves on Earth. Thus we

see, beginning with Giotto's pictures, the faithful portrayal of

the individual in Nature and in Man. It is no mere chance that

the paintings ascribed to Giotto in the upper church at Assisi

deal with the life of St. Francis, for there is a deep inner

connection of soul between Giotto and Francis of Assisi —

St. Francis, the religious genius, bringing forth out of a

fervent life of soul his sympathy with all the growth of Nature

upon Earth; and Giotto, imitating, to begin with, St. Francis'

way of feeling, St. Francis' way of entering into the spirit and

soul of the world.

Thus we see the

stream of evolution leading on from Cimabue's rigid lines and

two-dimensional conception, to Giotto, in whose work we see

increasingly the portrayal of the natural, individual creature,

the reality of things seen; we see things standing more and more

in space, rather than speaking to us out of the flat surface.

We will now give

ourselves up to the immediate impression of Giotto's pictures,

one by one. We shall see his growing appreciation of the

individual human character and figure. Giotto shows himself with

all the greater emphasis inasmuch as his pictures deal with the

sacred legend, and so he tries to reproduce in the outward

expression the inmost and intensest life of the soul.

Now, therefore, we

shall have before us a series of Giotto's pictures, beginning

with those that are generally regarded as his earliest. You will

still see in them the tradition of the former time, but along

with it there is already the human element, in the way in which

he knew it — the way that I have just described.

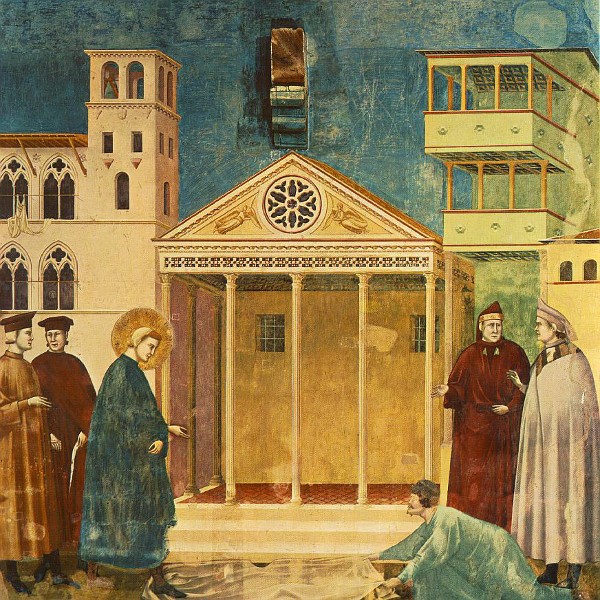

4. Giotto: Glorification of St. Francis. (San Francesco,

Assisi)

5. Giotto: Madonna enthroned. (Alter-piece, Santa Croce,

Florence.)

6. Giotto: Presentation in the Temple, (San Francesco,

Assisi.)

7. Giotto: Apparition in Arles. (San Francesco, Assisi.)

8. Giotto: The Miracle of the Spring. (San Francesco,

Assisi.)

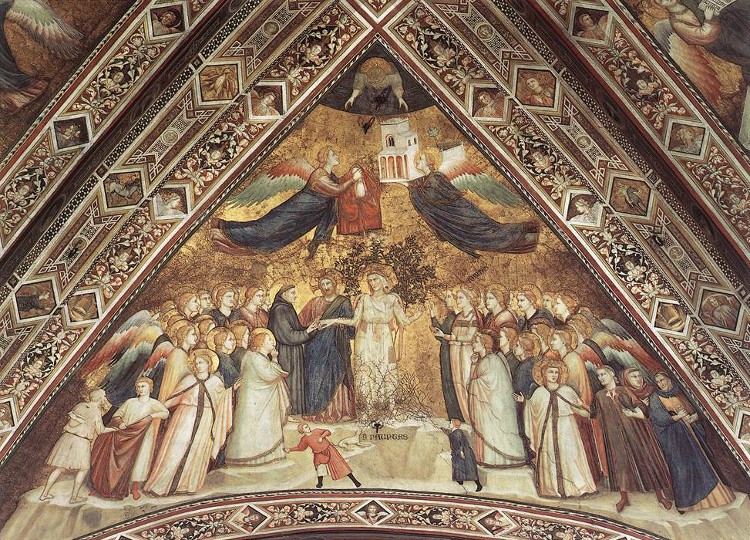

9. Giotto: Poverty. (San Francesco, Assisi.)

10. Giotto: Awakening of the Youth of Suessa. (San

Francesco, Assisi.)

11. Giotto: The Mourning for St. Francis by the Nuns. (San

Francesco, Assisi.)

Thus gradually the

whole life of St. Francis was painted by Giotto; and everywhere

in his artistic work we find a feeling similar to that of St.

Francis himself. Even when you take the visionary elements in

these pictures, you will see how his effort is in every case to

paint them from within, so that the language of human feeling is

far more in evidence than in the pictures of Cimabue, who was

concerned only with the gazing inward of transcendent impulses

from spheres beyond the Earth. Again, in the faces themselves you

will no longer find the mere traditional expression, but you will

see in every case: The man who painted these pictures had really

looked at the faces of men.

12. Giotto: Death of St. Francis. (Santa Croce,

Florence.)

Look at these last

two pictures. Their inherent tenderness recalls to us the

beautiful fact that is related of the life of St. Francis. He had

long been working at his Hymn to Nature — the great and

beautiful hymn throughout which he speaks of his brothers and his

sisters, of sisters Sun and Moon and the other planets, and of

all earthly creatures. All that he had felt in loving, realistic

devotion of his soul, in sympathy with Nature, is gathered up so

wonderfully in this hymn. But the directness of his union with

all earthly Nature finds expression most of all in this beautiful

fact that the last verse wherein he addresses Brother Death was

written in the very last days of his life. St. Francis could not

sing the hymn of praise to Brother Death till he himself lay

actually on his deathbed, when he called to his brothers that

they should sing around him of the joys of death while he felt

himself going out and out into that World which was now to

receive his spirit. It was only out of the immediate, realistic

experience that St. Francis could and would describe his tender

union with all the world. Beautifully this is revealed in the

fact that while he had sung the Hymn of Praise to all other

things before, he only sang to Death when he himself was at

Death's door. The last thing he dictated was the final verse of

his great Hymn of Life, which is addressed to Brother Death, and

shows how man, when he is thrown back upon himself alone,

conceives the union of Christ with human life. Surely it cannot

be more beautifully expressed than in this picture, revealing the

new conception of human life that was already pouring from out

St. Francis, and showing how directly Giotto lived in the same

aura of thought and feeling.

13. Giotto: Joachim and the Shepherds. (Capella Madonna,

Padua.)

I have inserted

this later picture, so that you may see the progress Giotto made

in his subsequent period of life. You see how the figures here

are conceived still more as single human individuals. In the

period from which the former pictures were taken, we see the

artist carried along, as it were, by the living impulses of St.

Francis. Here in this picture, belonging as it does to a later

period of his life, we see him coming more into his own. We will

presently return to the pictures more immediately following his

representations of St. Francis.

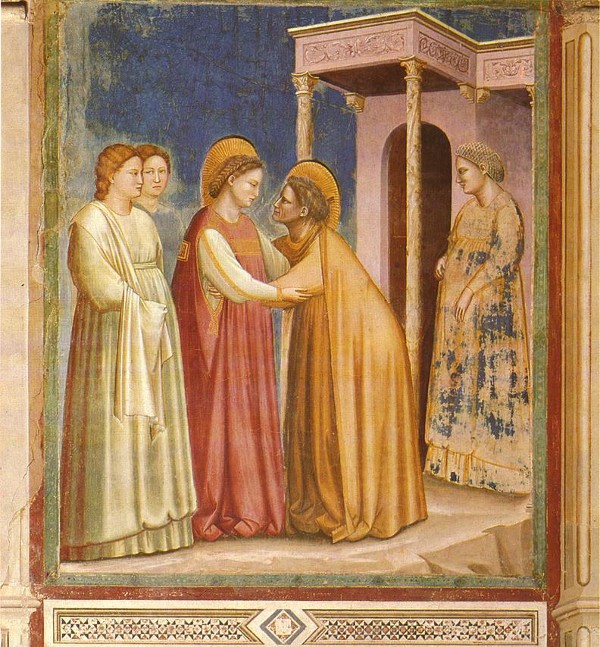

14. Giotto: The Visitation. (Capella Madonna dell' Arena,

Padua.)

This, too, is from

his later period, showing a consideraby greater realism than

before.

15. Giotto: Marriage of the Virgin. (Capella Madonna

dell'Arena, Padua.)

Also of his later

period.

16. Giotto: The Baptism of Christ. (Capella Madonna dell'

Arena, Padua.)

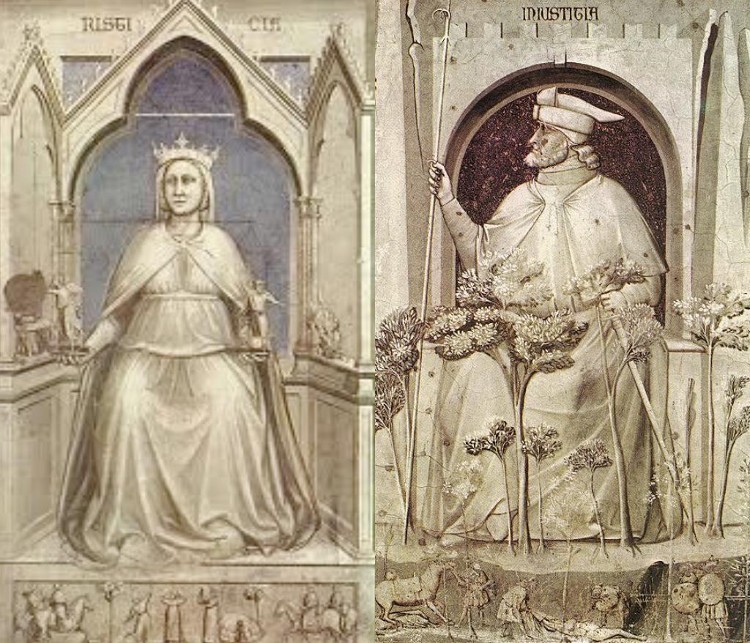

17. Giotto: Justice and Injustice. (Capella Madonna dell'

Arena, Padua.)

In such pictures we

see how natural it was to the men of that age to express

themselves in allegories. The conditions of life undergo immense

changes in the course of centuries. It was a tremendous change

when the life that had found expression in pictures at that time,

passed over into that in which we live today, which takes its

course more in thoughts and ideas communicated through the medium

of books. This was a far greater revolution than is generally

realised. The desire to express oneself in allegories was

especially strong in that age. It is most interesting to see how

in such a case artistic realism is combined with the striving to

make the whole picture like a Book of the World in which the

onlooker may read.

18. Giotto: St. Francis submits the Rules of his Order to the

Pope. (Santa Croce, Florence.)

This picture is

related once more the earlier art of Giotto — springing as

it does from his increasing entry into the whole world of feeling

of St. Francis of Assisi.

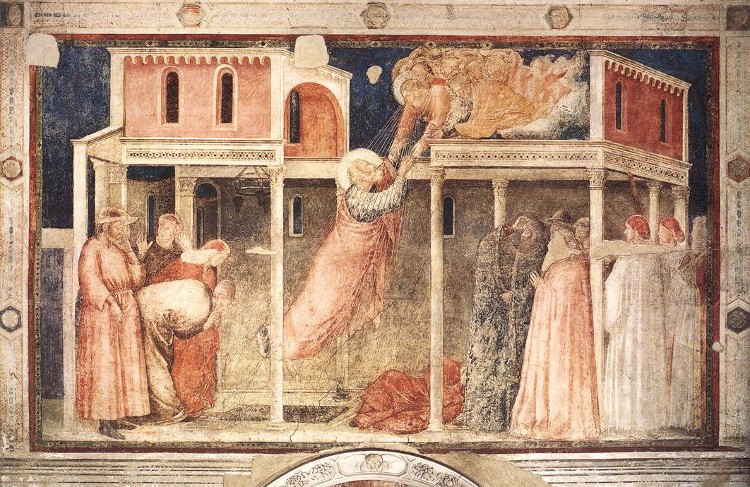

19. Giotto: The Ascension.of John the Evangelist. (Santa

Croce, Florence.)

20. Giotto: St. John in Patmos. (Santa Croce,

Florence.)

Beautifully we see

how the artist seeks to represent the inner life of St. John,

bringing forth out of his heart his inner connection with the

great World. This, then, is St. John, writing, or at least

conceiving, the Apocalypse.

21. Giotto: The Raising of Lazarus.

22. Giotto: The Flight into Egypt.

23. Giotto: The Annunciation to St. Anne.

24. Giotto: The Resurrection of Christ. (Capella Madonna

dell' Arena, Padua.)

25. Giotto: The Crowning with Thorns. (Capella Madonna

dell' Arena, Padua.)

26. Giotto: The Last Supper. (Capella Madonna dell' Arena,

Padua.)

27. Giotto: The Visitation. (San Francesco, Assisi.)

28. Giotto: Madonna. (Academy, Florence.)

We will insert,

directly after this Madonna by Giotto, the Madonna by Cimabue

which we have already seen, so that you may recognise the immense

difference in the treatment of the sacred figure. Observe —

despite the obvious persistence of the old tradition — the

realism of this picture, in the eyes, the mouth, and the whole

conception of the Jesus child. We have before us human beings,

copied from the reality of earthly life, looking out from the

Earth into the World. Compare this with Cimabue's picture, where

we rather have before us an original spiritual vision

traditionally handed down — where Beings gaze from realms

beyond the Earth into this world.

29. Cimabue: Madonna enthroned. (Academy, Florence.)

(This is No. 1 repeated.)

However much in the

composition is reminiscent of the former picture, you will see,

even in the way the lines are drawn, the immense difference

between the two.

30. Giotto: The Last Judgment. (Detail.) (Capella Madonna dell'

Arena, Padua.)

31. Giotto: Anger. (Capella Madonna dell' Arena. Padua.) Once

more an allegorical picture.

32. Giotto: Mourning for Christ.

It is interesting

to compare this picture with the “Mourning for St.

Francis” which we saw before. The former was an earlier

work, while this belongs to a very late period in Giotto's life.

We will now insert the previous one once more so that you may see

the great progression. This picture is taken from the chapel in

Padua, where Giotto returned once more to the former legend.

33. Giotto: Mourning for St. Francis. (San Francesco,

Assisi.) No. 11 repeated.

Here, then, you see

how he treats a very similar subject so far as the composition is

concerned, at an earlier and at a much later stage in his career.

Observe the far greater freedom, the far greater power to enter

into individual details which the later picture reveals.

34. Giotto: The Feast of Herod. (Santa Croce, Florence.)

35. Giotto: The Appearance in Arles. (Santa Croce, Florence.)

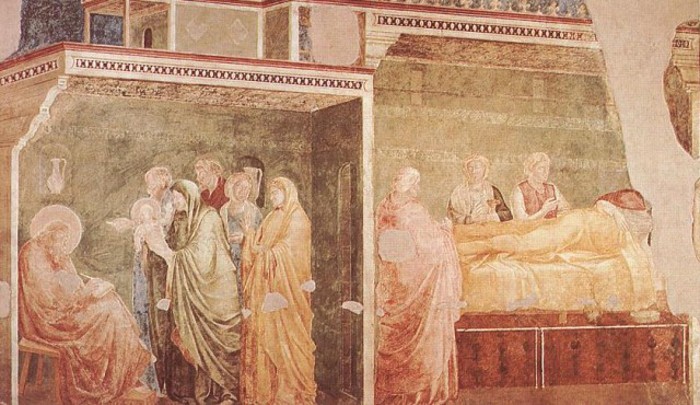

36. Giotto: Birth and Naming of John the Baptist. (Santa

Croce.)

37. Andrea da Firenze (School of Giotto): Doctrine of the

Church. (Spanish Chapel, Santa Maria Novella. Florence.)

38. Andrea da Firenze (School of Giotto): The Church

Militant. (Spanish Chapel, Santa Maria Novella,

Florence.)

This picture, the

Church Militant, is generally associated with the School of

Giotto. Here you see the rise of that compositional element which

was to play so great a part in the subsequent history of

painting. Quite a new inner life appears before us here. We may

describe the difference somewhat as follows:

If we consider the

evolution of Christianity until the time of Dante and Giotto, we

shall find a strong element of Platonism in its whole way of

feeling. Far be it from me to mislead you into the belief that it

contained the Platonic Philosophy; but Platonism, that is to say,

a feeling and conception of the world which also finds expression

in the philosophy of Plato, where man looks up into a sphere

beyond the Earth, and does not carry into it anything that

proceeds from the human intellect. After Giotto's time a

theological, Aristotelian element entered more and more into the

Christian world of feeling. Once again I do not say the

philosophy of Aristotle, but a theological, Aristotelian quality.

Men tried, as it were, to see and summarise the world in

systematic conceptions such as you see in this picture, rising

upward from a world below to a middle and thence to a higher

world. Thus was the whole of life systematised through and

through in an Aristotelian manner. So did the later Church

conceive the life of man placed in the universal order. Past were

the times from which Cimabue still rayed forth, when men's

conception of a world beyond the Earth proceeded still from the

old visionary life. Now came a purely human way of feeling; yet

the desire was, once more, to lead this human feeling upward to a

higher life — to connect it with a higher life, only now in

a more systematic, more intellectual and abstract way. And so, in

place of the Earlier Art, creating as from a single centre of

spiritual vision, there arose the new element of composition. See

the three tiers, rising systematically into higher worlds from

that which is experienced and felt below. Observing this in the

immediate followers of Giotto, you will already have a

premonition, a feeling of what was destined to emerge in the

later compositions. For who could fail to recognise that the same

spirit which holds sway in the composition of this picture meets

us again in a more highly evolved, more perfect form, in

Raphael's Disputa.

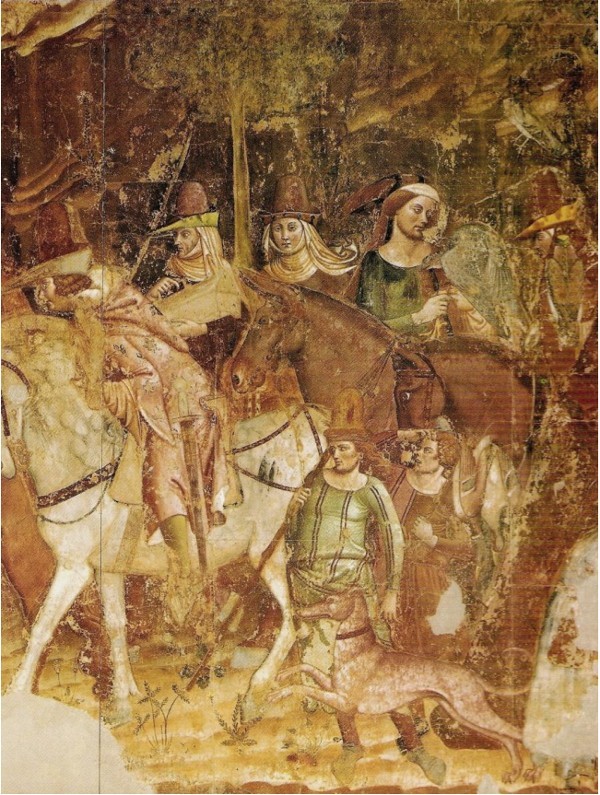

39. Andrea da Firenza (School of Giotto): The Church

Militant. (Detail.) (Santa Maria Novella, Florence.)

See how the

spiritual events and processes of earthly life are portrayed in

the grouping of the human figures. It is the same artistic

conception which emerges in Raphael's great picture, generally

known as the 'School of Athens.' Human beings are placed together

to express the relationships that hold sway in earthly life.

40. Andrea da Firenze. (School of Giotto): The Church

Militant. (Detail.)

I beg you

especially to observe the unique way in which the fundamental

idea comes to expression here: in the background the mighty

building of the Church, and then, throughout the picture, the

power going forth from the Church dignitaries, poured out into

the world of the common people. Look at the expression of the

faces. See how the artist's work is placed at the service of this

grand idea: The rule of the Church raying out over the Earth. You

may study every single countenance. Wonderfully it is expressed

— raying outward from the centre — how each single

human being partakes in the impulse that is thought to proceed

from the Church through all the souls on Earth. The physiognomies

are such that we see clearly: The whole thing was done by an

artist who was permeated by this idea, and was well able to bring

to expression in the countenance of men what the Church Militant

would, indeed, bring into them. We see it raying forth from every

single face. I beg you to observe this carefully, for in the

later pictures which we shall see afterwards it does not come to

expression with anything like the same power. Though the

fundamental idea of the composition — expressed so

beautifully here, both in the grouping of the figures and in the

harmony between the grouping and the expressions of the faces

— though the fundamental impulse was retained by later

artists, nevertheless, as you will presently see for yourselves,

it was an altogether different element that arose in their

work.

Look at the dogs

down here: they are the famous Domini Canes, the hounds of

the Lord, for the Dominicans were spoken of in connection with

the hounds of Lord. Angelico represents these Domini Canes

in many of his pictures.

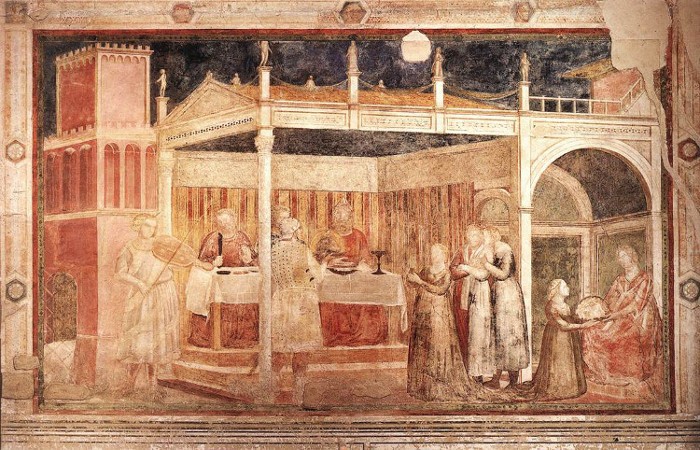

41. Tommaso Fini (Masolino): Feast of Herod.

(Tapistry, Castiglione d'Olona.)

Here we come a

stage further in artistic evolution. The following developments

may be said to have proceeded from the stream and impulse of

which Giotto was the great initiator. But from this source a

two-fold stream proceeded. In the one, we see the realistic

impulse emancipating itself more and more from the Spiritual. In

Giotto and in the last two pictures the Spiritual still enters

in, everywhere; for, after all, this impulse proceeding from the

Church Militant throughout the World is conceived as a spiritual

thing. Every single figure in the composition is such that we

might say: Just as St. Francis himself lived after all in a

spiritual world (albeit lovingly, realistically inclined through

his soul to the earthly world around him), Giotto and his pupils,

with 'however loving realism they grasped the things of this

world, still lived within the Spiritual and could unite it with

their conception of the single individual on Earth. But now, as

we come on into the 14th and 15th century, we see the longing,

faithfully to portray the individual and Natural, emancipating

itself more and more. There is no longer that strong impulse to

see the vision as a whole and thence derive the single figures,

which impulse was there in all the former pictures, even where

Giotto and his pupils went to the Biblical story for their

subjects. Now we see the single figures more and more emancipated

from the all-pervading impulse which, until then, had been poured

out like a magic broach ever the picture as a whole. More and

more we see the human figures standing out as single characters,

even where they are united in the compositions as a whole. Look,

for example, at the magnificent building here. Observe how the

artist is at pains, not so much to subordinate his figures to one

root-idea, as to represent in every single one a human

individual, a single character. More and more we see the single

human characters simply placed side by side. Though undoubtedly

there is a greatness in the composition, still we see the single

individuals emancipated naturalistically from the idea that

pervades the picture as a whole.

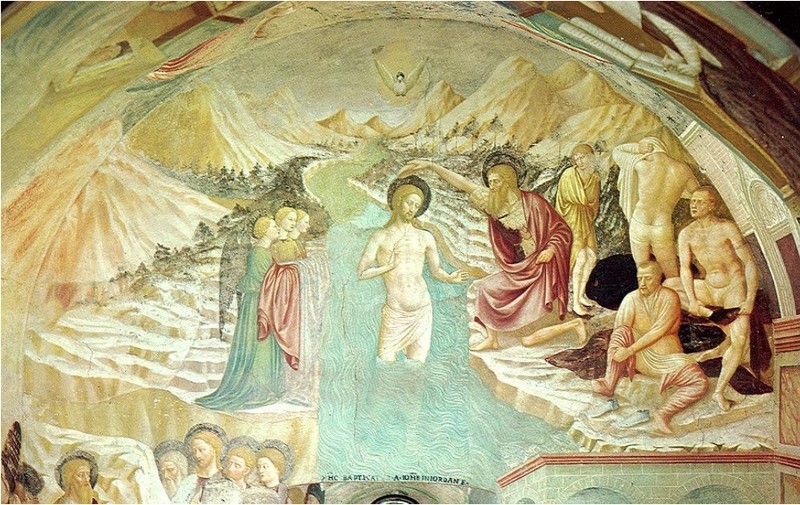

42. Masolino: The Baptism of Christ. (Baptistery.

Castiglione d'Olona.)

Even in this

Biblical picture you can see how the expressions of the several

figures are emancipated from the conception as a whole. Far more

than heretofore, the artist's effort is to portray even the

Christ in such a way that an individual human quality comes to

expression in Him. Likewise the other figures.

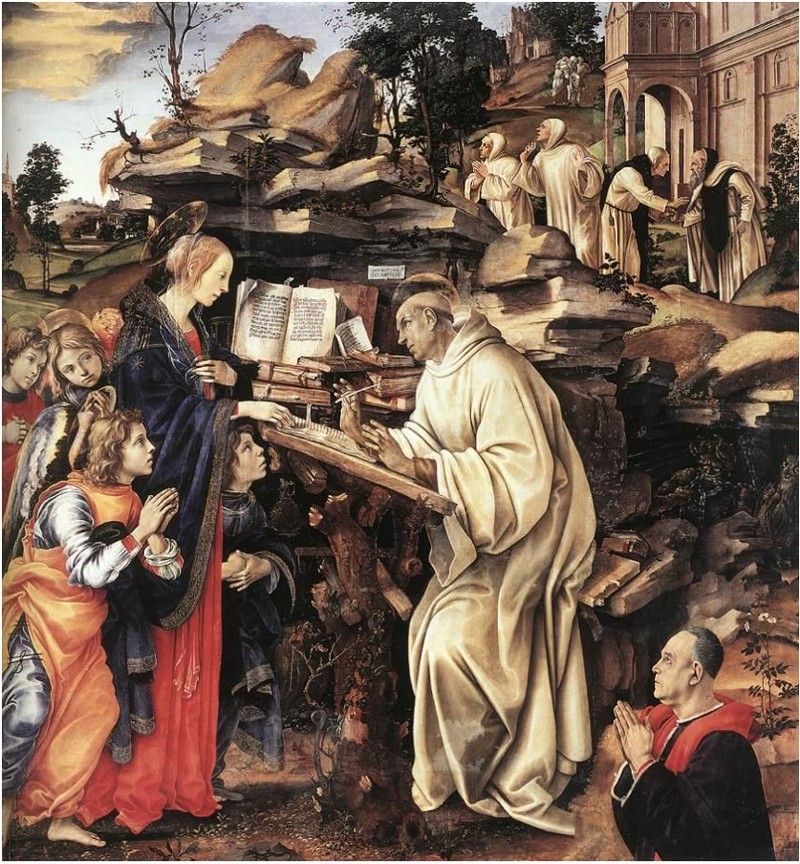

43. Filippino Lippi: Vision of St. Bernard.

(Florence.)

In this picture you

can already lose the feeling of one idea pervading the whole.

See, on the other hand, the wonderful expressions of the faces in

Filippino Lippi's work, both in the central figure of the

visionary and in the lesser figures. In every case the Human is

brought out. Thus we see the one stream, proceeding from the

source to which I just referred, working its way into an ever

stronger realism, till it attains the wondrous inner perfection

which you have before you in this figure of St. Bernard as he

receives his vision.

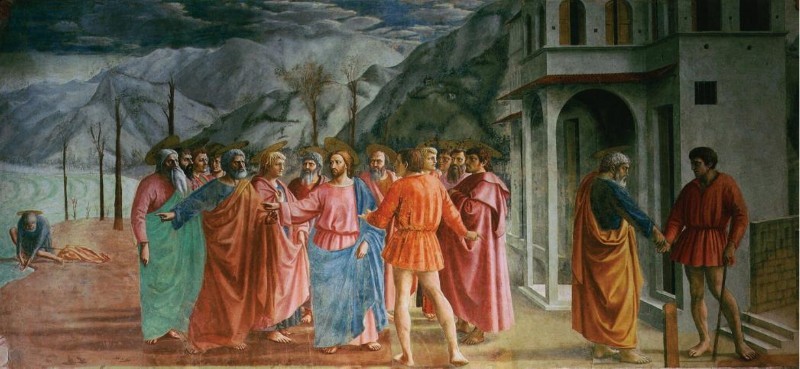

44. Masaccio: The Tribute Money. (Capella

Brancacci-Carmine, Florence.)

Here you see a

wonderful progression in human feeling. Looking at this work of

Masaccio's, you can take a keen interest in every single figure,

in every single head of these disciples grouped around the

Christ. Look, too, how the Christ Himself is individualised.

Think of the tremendous progress in characterisation, from the

pictures which we saw before, to this one. Observe the transition

in feeling. Heretofore it was absorbed in the Christian cosmic

conception. Now it has passed over to the renewed conception of

the Roman power. Feel in this composition, in the expressions of

the several figures, how the Roman concept of power is expressed.

A little while ago we say the Rule of the Church Militant pouring

out as a spiritual force over the whole. Here, for the most part,

are highly individualised figures — men who desire power

and who join together for the sake of power, while in the former

case it was a spiritual light which shone through all their

faces. In the earlier pictures, each was to be understood out of

the whole, while here we can but grasp the whole as a summation

of the individuals, each of whom is, in a sense, a power in

himself. With all the greatness of the composition — the

figures grouped around the mighty one, the Christ, mighty through

His pure spiritual Being, — still you can read in the

expressions of these men: ‘Ours is, indeed, a kingdom not

of this world; yet it shall rule this world,’ — and,

what is more, rule it through human beings, not through an

abstract spiritual force. All this is expressed in the figures of

these men. So you see how the human and realistic element becomes

more and more emancipated, while the artist's power to portray

the individual increases. The sacred legends, for example, are no

longer represented for their own sake. True, they live on, but

the artists use them as a mere foundation. They take their start

from the familiar story, using it as an occasion to represent the

human being.

45. Masaccio: Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise.

(Capella Brancacci-Carmine. Florence.)

See how the

artist's attention is directed not to the Biblical story in

itself but to the question: How will human beings look when they

have been through the experience of Adam and Eve? We must admit

that for his time the artist's answer is magnificent.

46. Ghirlandajo: Portrait, Framseslo Sassetti and Son.

(London.)

I need scarce make

a comment. With Ghirlandajo we come to a time when the faculty to

portray man as man — to represent what is purely human in

his life — has reached a high level of perfection.

47. Ghirlandajo: Last Supper. (Fresco.) (Ognissanti.

Florence.)

Henceforth the Last

Supper is no longer merely represented (as in the picture that we

saw just now) so that the vision of those that behold it may be

kindled to an experience of the sacred action. No; the story of

the Last Supper is now taken as an opportunity to represent the

human beings. Though it is not yet so much so as in some later

pictures, nevertheless, we can already study here the

physiognomies of the disciples one by one, observing how their

human characters are working under the impression that has been

kindled in their souls. Such pictures bring home to us the

immense change in the whole artistic conception.

48. Signorelli: The Sermon of Anti-Christ. (Orvieto.) The

same comments would apply to this picture.

49. Mantegna: Madonna. (Louvre. Paris.)

So, too, with the

problem of the Madonna: the artists now are more concerned to

bring out what is human and feminine in the Madonna than to

represent the sacred fact. The sacred legend lives on; and, being

familiar to all, is made use of to solve problems of artistic

realism and to bring out the individual and human.

50. Andrea Mantegna: San Sebastian. (Vienna.)

51. Andrea Mantegna: Parnassus. (Louvre. Paris.)

In these artists,

as the last pictures will illustrate, the Human impulse has

already grown so strong that they no longer feel the same

necessity to choose their subjects from the sacred legend. You

can scarcely imagine the entry into Giotto's pictures of any

other than a Christian subject. But when the Christian legend

came to be no more than the occasion for the artists to portray

the human being, they were presently able to emancipate the human

subject from the Christian Legend. So we see them going forward

to the art of the Renaissance, growing more and more independent

of Christian tradition.

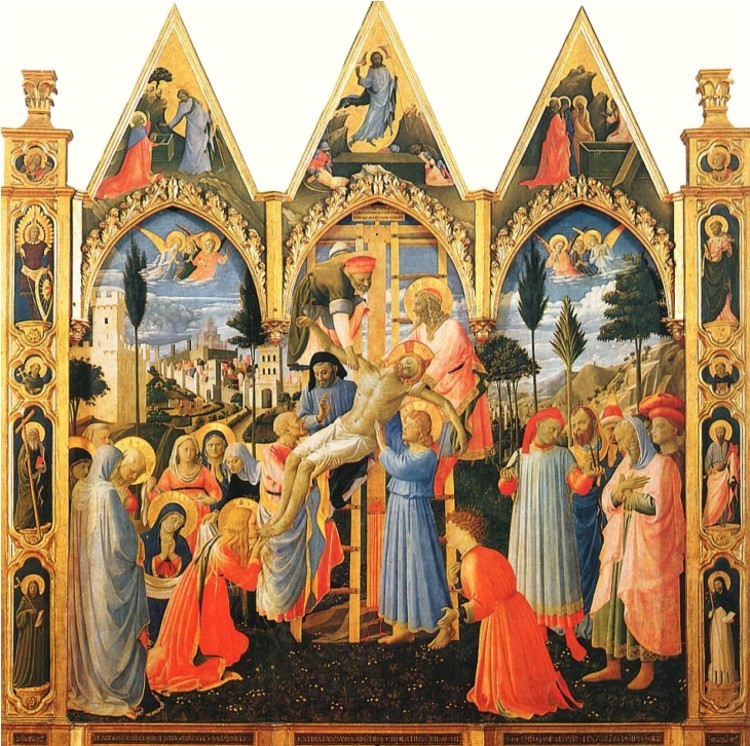

52. Fra Angelico: Descent from the Cross. (Academy.

Florence.)

Having shown a

number of pictures representing the realistic stream, if so we

may call it — the seizing of the Human on the Earth,

liberated from the Supersensible — we now come to the

second stream above-mentioned, of which Fra Angelico is one of

the greatest representatives.

It is, if I may so

describe it, a more inward stream,a stream more of the soul. The

artistic evolution which we followed hitherto was taken hold of

more by the Spirit. In Fra Angelico we see the Heart, the soul

itself, seeking to penetrate into the human being. It is

interesting to see once more, in the wonderfully tender pictures

of this artist, the attempt to grasp the individual and human,

yet from an altogether different aspect, more out of the soul.

Indeed, this lies inherent in the peculiar colourings of Fra

Angelico, which, unhappily, we cannot reproduce. Here everything

is felt more out of the soul, whereas the emancipation of the

Human which appeared in the other realistic stream, came forth

more out of the human Spirit striving to imitate the forms of

Nature.

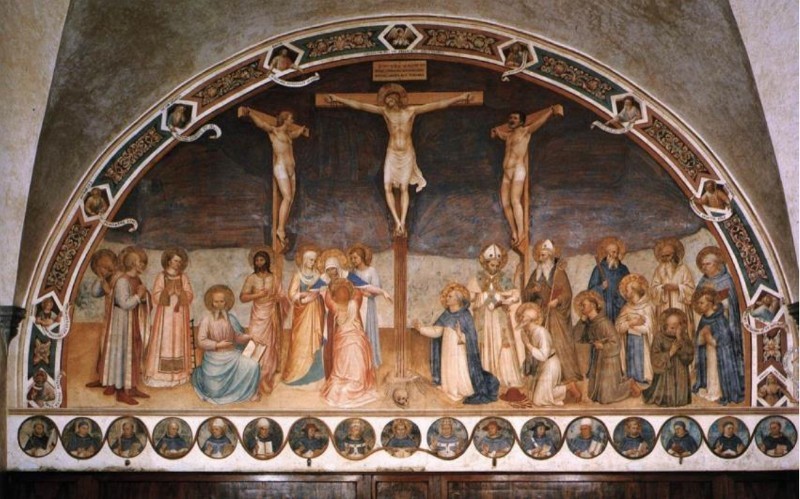

53. Fra Angelico: Crucifixion. (San Marco. Florence.)

It is by the path

of the soul, as it were, that the soul-content of Christianity

pours in through Fra Angelico. Hence the phenomenon of Fra

Angelico is so intensely interesting. Formerly, as we have seen,

a supersensible and spiritual content poured through the

evolution of Christianity, and took hold also of the world of

Art. Then the attention of man was turned to the world of Nature

— Nature experienced by the soul of man. We have seen how

the same impulses, living as a simple religious enthusiasm in St.

Francis of Assisi, found artistic expression in Giotto.

Henceforth, man's vision was impelled more and more to an outward

naturalism. But in face of all this realism, his inner life seeks

refuge, as it were, in the soul's domain, tending, again, rather

to melt away the sharper lines of individuality, but striving all

the more intensely to express itself, as a life of soul, in outer

form. For the soul's life holds sway, pervading all the details

in the work of Fra Angelico. It is as though the soul of

Christianity took flight into these tender pictures, so widely

spread abroad, though the most beautiful are undoubtedly in the

Dominican Monastery at Florence.

Thus while the

Spirit that had once held sway in vision of the Supersensible was

now expended on the vision of the Natural, the soul took refuge

in this stream of Art, which strove not so much to seize the

physiognomy — the Spirit that is stamped on the expressions

of the human countenance and of the things of Nature — but

rather to convey the life of soul, pouring outward as a living

influence through all expression.

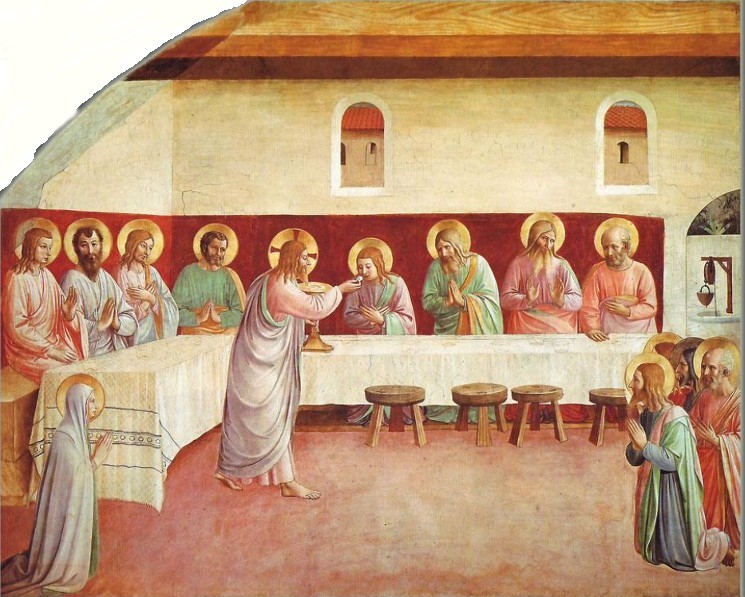

54. Fra Angelico: The Last Supper. (San Marco,

Florence.)

You will remember

the picture of the Last Supper which we showed just now. There,

everything depended on an answer to the question: How does Nature

reveal the Spirit? How does Nature impress on the external

features of men the signature of their experience in this event?

Here, on the other hand, you see how all the characters are

concentrated on a single feeling, and yet this single quality of

soul finds living expression in them all. Here is essentially a

life of soul, expressed through the soul; while in the former

picture it was a life of the Spirit, finding a naturalistic

expression. Down to the very drawing of the lines you can see

this difference. Look at the wonderful and tender flow of line.

Compare it with what you will remember of the former picture of

the Last Supper.

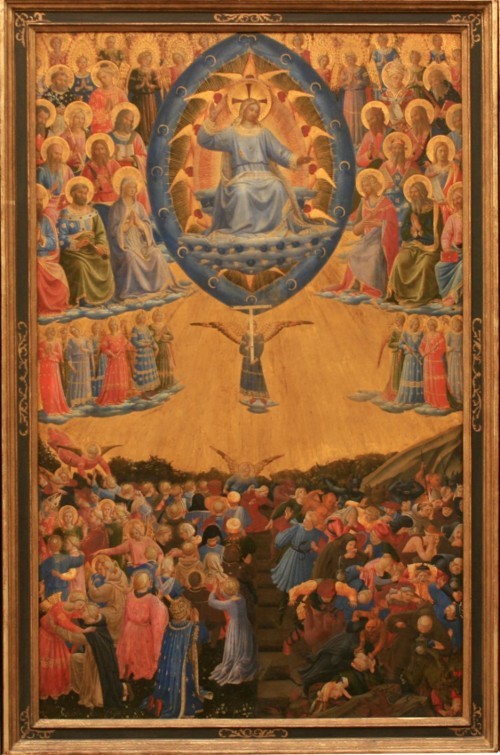

55. Fra Angelico: Coronation of the Virgin Mary. (San

Marco, Florence.)

See what a quality

of soul is poured like a magic breath over this picture.

56. Fra Angelico: (from) The Last Judgment. (Museum.

Berlin.)

57. Sandro Botticelli: Lucrezia Tornabuoni.

(Frankfort.)

It is interesting

how in Botticelli the same artistic impulse, which we found in

Fra Angelico, is transferred — if I may put it so —

to altogether different motives. Botticelli, in a certain

respect, is most decidedly a painter of the life of soul. Yet he

again emancipates, within the life of soul, the Human from the

general Religious feeling which pervades the work of Fra

Angelico. He emancipates the human working once more towards a

certain naturalism in the expressions of the soul.

Compare this

portrait with the head we saw before, by Ghirlandajo. In that

case something essentially spiritual found naturalistic

expression, while here we see an abundant life and content of the

soul even in the drawing of the lines.

58. Sandro Botticelli: Adoration of the Magi. (Uffizi.

Florence)

59. Sandro Botticelli: Pieta. (Alte Pinakothek,

Munich.)

60. Sandro Botticelli: Coronation of the Virgin. (Uffizi.

Florence)

Following on Fra

Angelico, we have shown a series of Botticelli's so as to gain an

impression of the progress in the painting of the soul's life, in

contrast to the Spirit which we found in Masaccio and

Ghirlandajo. These, then, were the two directions that grew

directly out of the impulses proceeding from Giotto —

impulses handed down through Giotto, and through Donatello in

another sphere, down to these painters.

In the further

course of evolution on these lines, we now come to the great

Renaissance painters, of whom I still wish to show you a few

pictures in this lecture. When we have a picture like this of

Botticelli's before us, we realise the extraordinary intensity of

progress from the 14th to the 15th and on into the 16th century

— from the portrayal of the purely Human, In such artists

as Ghirlandajo we see the Spiritual, absorbed into the sphere of

Nature, brought to a high level of expression. Here in this other

stream we see a rich life of soul, come to expression, even in

the draughtmanship. In course of time men had attained the

knowledge of the human form, with all its powers of expression.

It was as though, from the starting-point of Heaven, Earth had

been conquered by mankind. That deepening of life which had come

about through Christianity passed more and more into the

background, and it was as though the object now were to

understand man as such in a far deeper way. The heavenly domain

became a path of progress, towards the more perfect expression of

the inner being of man as it stamps itself upon his outer

features, and upon all that comes forth outwardly in the

relationships of men to one another, in their life together. It

is the conquest of the realm of Man, by the most varied paths,

which comes before us here so wonderfully.

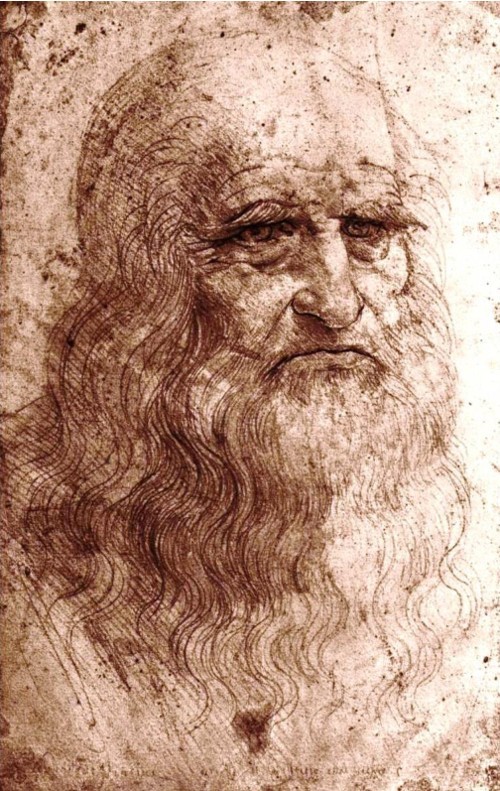

And now we see the

union of all these impulses in the great artists, Leonardo,

Michelangelo and Raphael. Let us observe a few of Leonardo's

pictures. We shall find in him a synthesis of the varied

strivings which came be ore us in the other pictures. For in a

high degree, the Leonardo da Vinci, there is a working-together

of the Spiritual with the life of the soul — in his

drawing, in his composition and in his power of expression.

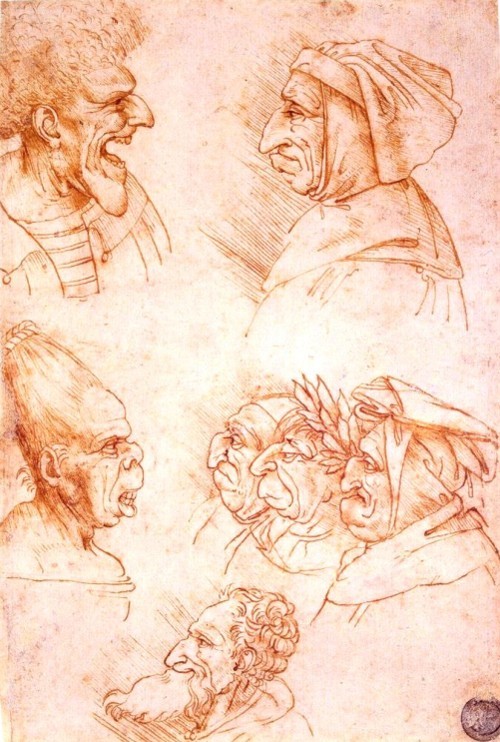

61. Leonardo da Vinci: Sketches and Caricatures.

(Windsor.)

To begin with I

have selected some sketches and drawings by Leonardo, from which

you may see how he endeavoured to study man in a fully realistic

way. This, of course, was in a time when all that had been gained

in the former periods was there to influence the artist. It is

characteristic of Leonardo how radically he seeks to bring out

the full expressiveness of man; he tries to seize the human being

as a whole, and bring him forth to perfection in his drawing. He

seeks to enhance his power of expression to the highest point by

studying and holding fast all human needs. This was only possible

in the flower of an artistic epoch containing all the works which

we have seen today — the penetration of the human being in

the Spirit and in soul.

62. Leonardo da Vinci: Madonna detta. (Eremitage, St.

Petersburg.)

More, as I said,

you see united all that had formerly been striven for by separate

paths.

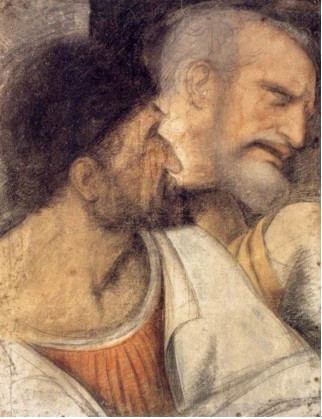

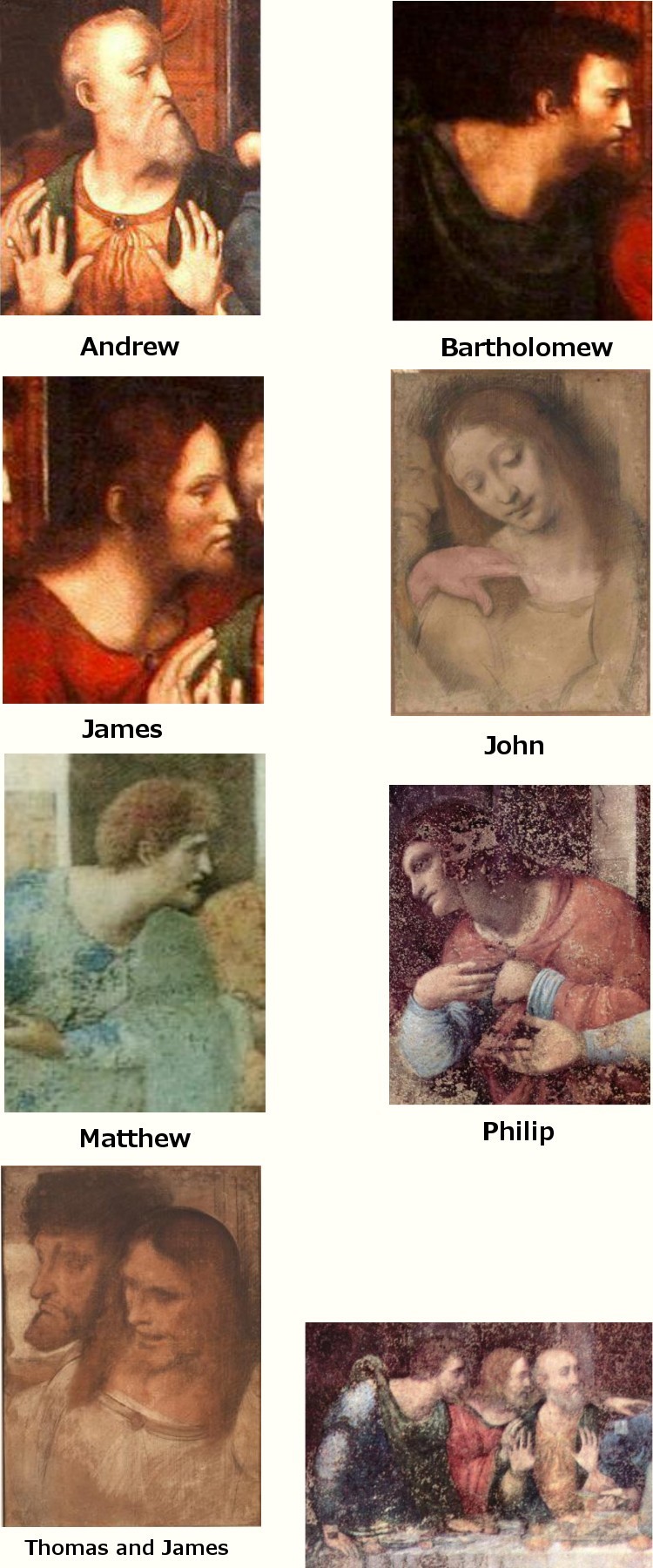

63. Leonardo da Vinci: Heads of Apostles. (Weimar.)

These are the heads

of the Apostles from the famous fresco at Milan, — the Last

Supper, which, also, is scarcely visible today, for only isolated

patches of colour now remain. We see that in this great artistic

epoch the sacred legend merely provided a foundation for the

working-out of human characters. Especially in his Last Supper,

Leonardo is at pains to study the single human characters. We see

him working very, very long at this wonderful picture, for he

wanted to study the human characters in all detail. We know how

often he disappointed his clients — the dignitaries of the

Church. Thus, after long labour, he had not finished Judas

Iscariot, and when the Abbot, high dignitary that he was, kept

pressing him to finish it at last, his answer was that hitherto,

alas, he had not been able to finish it since he lacked a model

for Judas Iscariot; but now the Abbot himself, if he would kindly

sit for him, would provide an excellent model for the

purpose.

64. Leonardo da Vinci: Last Supper.

64a. Leonardo da Vinci: Heads of Apostles. (Weimar.)

65. Leonardo da Vinci: Portrait of Himself. (Milan.)

66. Leonardo da Vinci: St. Jerome. (Vatican. Rome.)

67. Leonardo da Vinci: Adoration of the Magi. (Uffizi.

Florence.)

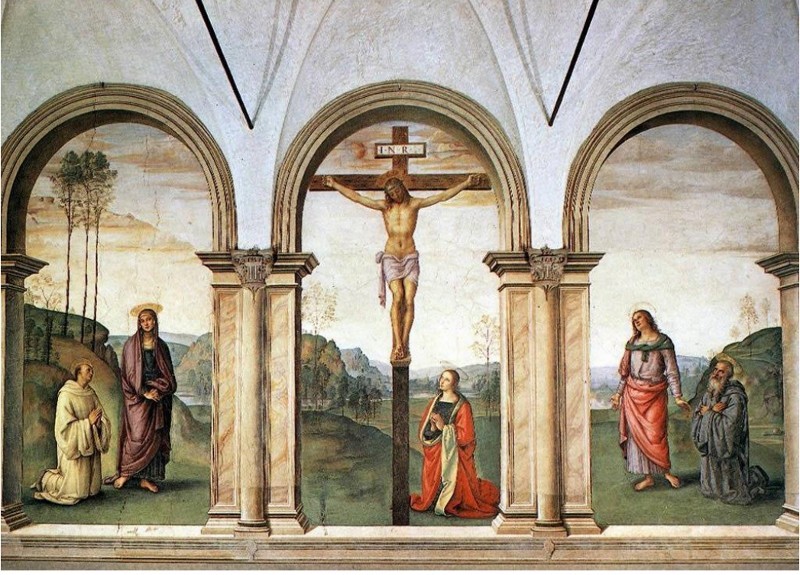

68. Perugino: Crucifixion: (Sta. Maria dei Passi.

Florence.)

We go on in this

classical epoch. I beg you to observe this picture by Perugino,

Raphael's teacher, to see how Raphael's art grew out of his

predecessor's. In Perugino a new element makes its appearance:

— a deep religious quality which tries to find expression

in the composition, combined with a powerfully architectural

imagination. On this, the greatness of Raphael very largely

depended.

69. Raphael and Perugino: The Betrothal.

Look at these two

pictures: You will see the one actually growing out of the other;

you will recognise how Raphael, starting from his teacher,

attained his greatness, receiving the ripest fruits from the

different streams which we have learned to know this evening;

Raphael brings soul and Spirit into his pictures and combines

them with that element of composition which came from his

especial schooling.

70. Perugino: Vision of St. Bernard. (Alte Pinakothek.

Munich.)

You will remember

the earlier picture of the 'Vision of St. Bernard' which we saw

this evening. Consider the great difference. In the former case

there was an effort to make the Spirit powerfully active in all

that was brought into the picture. Here we see a pure element of

composition, contriving to express what is, indeed, the chosen

motif of the picture but does not penetrate it fully. Perugino

cannot yet deepen his composition so that a living soul speaks

out of it. Nevertheless, we see how great a part this element of

composition plays in his school of painting.

71. Perugino: The Giving of the Keys to St. Peter.

(Sistine Chapel. Vatican. Rome.)

Here, then, where

Raphael receive' such powerful influences, we see the entry of an

element of composition. You will, of course, see how great a part

it plays in Raphael. In the former pictures we cannot speak of it

in the speak of it in the same way as here. The composition was,

rather, the result of a totality, — a totality which the

artist felt more as a living organism. Man, too, after all, is

composed; but though he is composed of head and arms and legs and

so forth, we cannot really call this a 'composition'; for in man

everything proceeds as from a centre, and we feel his composition

— of arms and legs, of head and trunk — as a natural

totality, a thing that goes without saying. Here in this picture

you not feel it as a natural totality, a thing that goes without

saying. You feel it definitely, purposely composed; whereas you

will find the earlier compositions flowing more out of a single

whole. Here, you see, the whole is placed together; it is

literally composed.

Proceeding,

therefore, from the 13th, 14th, 15th centuries, we recognise the

one stream which seeks to conquer Nature through the Spirit, and

leads on to a higher stage of realism. Side by side with it we

see another stream which seeks to conquer Nature from the aspect

of the soul. And now, coming across from Central and Eastern

Italy where Raphael and his predecessors had their home, we see

this power of composition, this working from the single parts

towards the whole, whereas all the former streams still contained

an echo of the working from the whole into the single parts, a

thing that you could see most strongly, for example, in that

composition representing the spiritual rule of the Church pouring

out into the world, where everything was conceived out of a given

unity, and nothing was built up out of the single details, as it

is in this case.

72. Raphael: Pope Leo X. (Pitti Gallery. Florence.)

See how the

spiritual element finds its way into the soul of Raphael —

I mean, all that has been achieved by that spiritual element

which grew into Naturalism.

73. Raphael: Pope Julius II. (Uffizi. Florence.)

74. Orcagna: Triumph of Death. (Campo Santo. Pisa.)

I have inserted

this last picture to show how the element of allegory still

worked on. I drew attention to it in Giotto. It worked on along

with all the other streams; indeed, it was the one thing that

more or less remained of the earlier more spiritual conception.

This one thing remains: — this element of abstract allegory

which is especially to be found in the pictures in the Campo

Santo at Pisa, magnificent as they are in many respects. It

belongs, indeed, to an earlier time. Nevertheless, I wanted to

show you how this allegorical element still worked on even in a

later age.

All these things,

then, were living in the feeling of the human being, — a

spiritual power and a life of soul poured out into Naturalism;

and withal, no longer an ability to grasp the whole as such, but

purposeful. composition. Lastly, the remnants of allegory.

75. Orcagna: Triumph of Death. Campo Santo. Pisa.)

76. Orcagna: Triumph of Death. (Campo Santo. Pisa.)

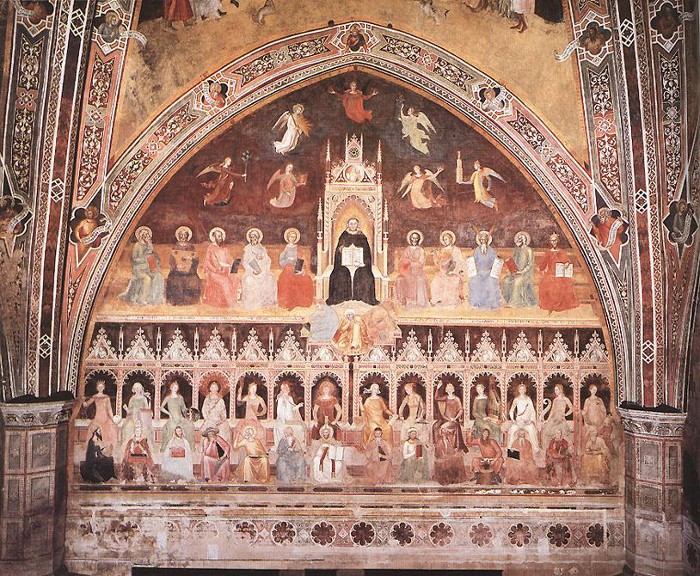

77. Francesco Traini: St. Thomas Aquinas. (Sta. Caterina. Pisa.)

In this picture you

see once more the working-on of allegory. It is intended to

represent the influence of the scholastic doctrine, on the one

hand downward to the Earth, even to the conquest of heresy, and

on the other hand upward into the heavenly regions where the rays

of what is living on the Earth are received into the midst of

sacred beings. What was conceived working, as it were, in the

spiritual substance of the Earth, is here expressed in allegory.

It is an allegory, but one derived from the reality. Here, then,

the last-named element — that of allegory — is taken

as a starting-point, not for the mere sake of allegory in itself,

but, rather, to express in allegory what they conceived as really

working, even as they represented it.

Thus we have tried

to understand the different streams. I will once more repeat

them: The Spirit striving into Naturalism; the life of soul,

growing ever more realistic in its expressiveness, even as the

artists grew more capable of portraying the soul's life in the

outward expression; the element of composition, placing together

single features in order that the whole might have a spiritual

effect; and, lastly, the element of allegory. We have traced

these influences, each and severally. Thus was built up what came

at last to full expression in the creations of Raphael,

Michelangelo and their successors. Throughout, we see a spiritual

force, passing through man by varied ways and channels, seeking

to conquer Nature. First we see the Spirit endeavouring to master

what comes to expression in the human being through the human

Spirit. Then the spiritual faculty of vision enters more and more

into man's grasp of outer Nature. Then, in such artists as Fra

Angelico and Botticelli, we see the entry of a life of soul. And

when the composition was no longer given as a matter of course

out of a spiritual vision, we witness the attempt to bring the

Spirit to expression by composition deliberately placed together,

in which direction Raphael achieved the highest eminence. Lastly,

we see how the longing to give voice to the great cosmic process

led to Allegory, and how Allegory itself grew into Realism, as

you can see in this very picture. Indeed, in Raphael it grew once

more into a perfectly natural spirituality, a spirituality that

works as a matter of course. I beg you to remember such a

composition as his 'St. Cecilia' at Bologna. Here we still see, a

central figure is set down with obviously allegorical intention,

seeking to represent the soul-life of the human being in its

connection with the Universe.

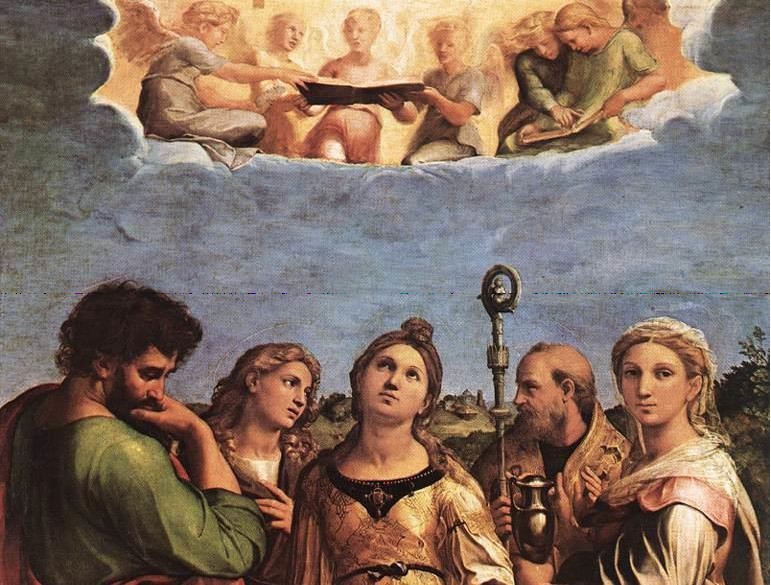

78. Raphael: Saint Cecilia (Bologna, Pinacoteca)

In Raphael's St.

Cecilia there is the central figures standing in the midst; yet

the thing has gone so far that the allegorical quality is

completely overcome, obliterated, as it were, so much so that

there is much argument today as to what this 'St. Cecilia' is

meant to express, though they need only to look up their

Calendars to see how closely the picture adheres to the

tradition. For in the legends of the Saint you will find all that

Raphael included in this wonderful creation. But to such an

extent did he attain Nature's power to express the Spirit and the

Soul in form, that we no longer notice all the Allegory that

underlies the picture. And that, indeed, is the great thing in

this epoch, attained by Michelangelo and Raphael. In all the

former streams, the impulses from which they come are

recognisable. Here, each and all, they are overcome to

perfection, with the attainment of a pure and fresh and free (for

that time fresh and free) vision and reproduction of the reality

around us, in its natural material content and in its soul and

Spirit. The works created by this age were based, indeed, on the

preceding evolution which we have described. Here, above all, we

recognise how such achievements must be preceded by many lines of

evolution, which, only inasmuch as they take their start from the

Spirit, lead to the recognition of the Spirit in the outer world.

Man must first seek the Spirit, then will he find the Spirit in

the outer world. Man must first feel and experience the Soul,

then will he find them also in the external Nature. Thus we see

how the Spiritual that was still at work in Cimabue, worked on

after him in Giotto, who in turn carried it outward as a means to

understand the forms of Nature. We see the spiritual content

radiating still from Giotto's work, applied still further by his

successors to apprehend the Spirit in the world of Nature. We see

how the deep soul-impulse that came through Francis of Assisi,

taking hold of the life of the soul in man himself, was expressed

with a certain artistic perfection in the Christian piety of Fra

Angelico. This impulse once again rays forth into the world; we

have the essence of Botticelli. Then (if I may so express it),

out of a kind of memory of the totality of vision which is lost,

the artist tries to piece together the single features into a

composition, thus creating a totality once more, so that the

Spirit — which was lost to immediate vision, to be used in

a new way in the taking hold of Nature, — might work again

from the totality. And at length we see, in the quest of

Allegory, the search for means of expression, leading in the last

resort to the overcoming of all Allegory; to the finding the

means of expression even in Nature herself. For to him who first

sets out to seek it, the free and open-minded vision of the outer

World itself will give what he desires. Nature herself is

allegorical; yet does she nowhere impose her allegories on us, or

let us see them outwardly as such. Man must learn what is there

to be read in the book of Nature. But at first he often has to

learn his reading in clumsy devious byways. In such a work as the

picture of St. Thomas which we saw before, we witness still a

clumsy and unskillful reading of the book of Nature. In Raphael's

St. Cecilia, on the other hand, we have a reading which contains

no longer any Allegory, no longer any of that abstract element

which has not yet arisen to the full height of Art.

Thus I think we

shall have gained a conception, how the great epoch of the

Italian Renaissance gradually came into being. Again and again, I

think, the vision of man will be directed to these times, to this

artistic evolution; for it lets us gaze so deeply into the life

and working of piety, of Wisdom and of Love in the human soul,

combined with the artistic fancy, striving to reproduce Nature

with a fresh and open mind. It lies not in the mere imitation of

Nature, but in the faculty of Man, with all that he has found in

his own soul, to discover again in Nature what is already there

in her, akin to the inmost experiences of the human soul. This, I

venture to hope, our descriptions today — however brokenly,

however imperfectly — may still have brought to light.

78a. Raphael: Detail of Saint Cecilia (Bologna, Pinacoteca)

|