In the future all teaching must be founded on a real psychology —

a psychology which has been gained through an anthroposophical

knowledge of the world. Of course it has been widely recognised that

instruction and education generally must be built up on psychology,

and you know that Herbartian pedagogy, for instance, which has

influenced great numbers of people, founded its educational standards

on Herbartian psychology. Now during the last few centuries and up to

recent times there has been something present in the life of man which

prevents a real practical psychology from coming into being. This can

be traced to the fact that in the age in which we now are, the age of

the Consciousness Soul, man has not yet reached the spiritual depth

which would enable him to come to a real understanding of the human

soul. But those concepts which have been built up in past times in the

sphere of psychology — the science of the soul — out of the

old knowledge of the fourth Post-Atlantean period, have become more or

less devoid of content to-day: they have become mere words. Anyone who

takes up psychology or anything to do with psychological concepts will

find that there is no longer any real content in the books on the

subject. They will have the feeling that psychologists only play with

concepts. Who is there to-day for instance who develops a really clear

conception of what mental picture or will is? In psychologies and

theories of education you can find one definition after another of

mental picture and of will, but these definitions will not be able to

give you a real mental picture, a real idea, either of mental picture

itself or of will. Psychologists have completely failed — owing

to an external, historical necessity, it is true — to make any

connection between the soul life of the individual human being and the

whole universe. They were not in a position to understand how the

soul-life of man stands in relation to the whole universe. It is only

by perceiving the connection between the individual human being and

the whole universe that it is possible to arrive at the idea of the

being “man.”

Let us look at what is ordinarily called mental picture. We must

develop this, as well as feeling and willing, in the children, and to

this end we must first of all gain a clear conception of the mental

picture. Anyone who looks with an open mind at what lives in men as

this activity will at once be struck by its image character. The

mental picture is of the nature of an image. And those who try to find

in it the character of existence or being are subject to a great

illusion. What would it be for us if it were “being”? We

certainly have elements of being in us also. Think only of our bodily

elements of being: to take a somewhat crude example: your eyes, they

are elements of being, your nose or your stomach, that is an element

of being. It will be clear to you that you live in these elements of

being, but you cannot make mental pictures with them. You flow out

with your own nature into the elements of being, and you identify

yourself with them. The possibility of understanding, of grasping

something with your mental pictures arises from the fact that they

have an image character, that they do not so merge into us that we are

in them. For indeed, they do not really exist, they are mere images.

One of the great mistakes of the last period of man's evolution during

the last few centuries, has been to identify being with thought as

such. Cogito ergo sum (I think therefore I am), is the greatest

error that has been put at the summit of recent philosophy, for in the

whole range of the Cogito there lies not the sum but the

non sum. That is to say, as far as my knowledge reaches I do

not exist, but there is only image.

Now when you consider the image character of mental picturing you must

above all think of it qualitatively. You must consider its mobility,

one might almost say its activity of being, but that might give too

much the impression of being, of existence, and we must realise that

even activity of thought is only an image activity. Everything which

is purely movement in mental picturing is a movement of images. But

images must be images of something; they cannot be merely images as

such. If you think of the comparison of mirror images you can say to

yourselves: out of the mirror there appear mirror images, it is true,

but what is in the mirror images is not behind the mirror, it exists

independently somewhere else. It is of no consequence to the mirror

what is to be reflected in it; all sorts of things can be reflected in

it. When we have thus clearly grasped that the activity of mental

picturing is of this image nature, we must next ask: of what is it an

image? Naturally no outer science can tell us this, but only a science

founded on Anthroposophy. Mental picturing is an image of all the

experiences which we go through before birth, or rather conception.

You cannot arrive at a true understanding of it unless it is clear to

you that you have gone through a life before birth, before conception.

And just as ordinary mirror images arise spatially as mirror images,

so your life between death and re-birth is reflected in your present

life and this reflection is mental picturing. Thus when you look at it

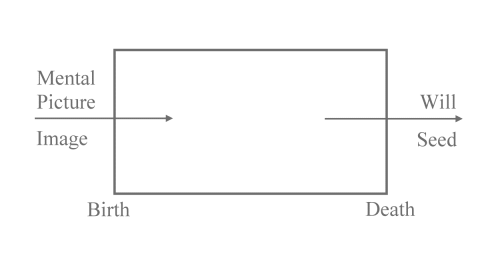

diagrammatically you must mentally picture the course of your life to

be running between the two horizontal lines bounded on the right and

left by birth and death.

You must then further represent to yourself that mental picturing is

continually playing in from the other side of birth and is reflected

by the human being himself. And it is because the activity which you

accomplish in the spiritual world before birth or conception is

rejected by your bodily nature that you experience mental picturing.

For true knowledge this activity is a proof, because it is an image,

of life before birth.

I want to place this first before you as an idea (we shall come back

to a real explanation of these things later) in order to show you that

we can get away from the mere verbal explanations which you find in

psychologies and theories of education, and arrive at a true

understanding of what the activity of mental picturing is, by learning

to know that in it we have a reflection of the activity which was

carried on by the soul before birth or conception, in the purely

spiritual world. All other definitions of mental picturing are of

absolutely no value, because they give us no true idea of what it is.

We must now investigate will in the same way. For the ordinary

consciousness will is really a very great enigma. It is the crux of

psychologists simply because to the psychologist will appears as

something very real but basically without content. For if you examine

what content psychologists give to will you will always find that this

content comes from mental picturing. As for will itself it has no

immediate real content of its own. Then again the fact is that there

are no definitions of will: these definitions of will are all the more

difficult because it has no real content. But what is will really? It

is nothing else but the seed in us of that which after death will be

reality of spirit and of soul. Thus when you picture to yourself what

will be our spirit-soul reality after death, and picture it as seed

within us, then you have will. In our drawing our life's course ends

with death on the one side, and will passes over beyond it.

Thus we have to picture to ourselves: mental picturing on the one

hand, which we must conceive of as an image from pre-natal life; and

will, on the other hand, which we must conceive of as the seed of

something which appears later. I beg you to bear clearly in mind the

difference between seed and image. For a seed is something more than

real, and an image is something less than real; a seed does not become

real until later, it carries within it the ground of what will appear

later as reality; so that the will is indeed of a very spiritual

nature. Schopenhauer had a feeling for this truth, but naturally he

could not advance to the knowledge that will is a seed of the

Spirit-Soul as it unfolds after death in the spiritual world.

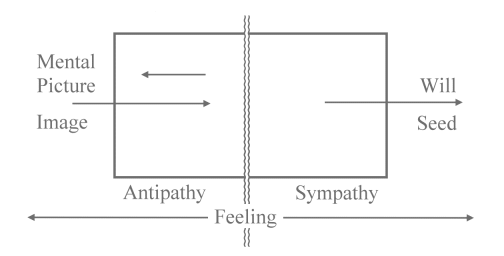

Now we have divided man's soul-life into two spheres, as it were: into

mental picturing, which is in the nature of image, and will, which is

in the nature of seed, and between image and seed there lies a

boundary. This boundary is the whole life of the physical man himself

who reflects back the pre-natal, thus producing the images of mental

picturing, and who does not allow the will to fulfil itself, thereby

keeping it continually as seed, allowing it to be nothing more than

seed. Now we must ask: what are the forces that really bring this

about?

We must be quite clear that in man there are certain forces which

reflect back the pre-natal reality and hold the after death reality in

seed. And now we come to the most important psychological concepts of

facts which are reflections of the forces described in my book

Theosophy

— reflections of sympathy and antipathy. Because we can no longer

remain in the spiritual world (and here we come back to what was said

yesterday) we are brought down into the physical world. In being

brought down into the physical world we develop an antipathy for

everything spiritual so that we radiate back the spiritual, pre-natal

reality in an antipathy of which we are unconscious. We bear the force

of antipathy within us, and through it transform the pre-natal element

into a mere mental picture or image. And we unite ourselves in

sympathy with that which radiates out towards our later existence as

the reality of will after death. We are not immediately conscious of

these two, sympathy and antipathy, but they live unconsciously in us,

and they signify our feeling, which consists continually of a rhythm,

of an alternating between sympathy and antipathy.

We develop within us all the world of feeling, which is a continual

alternation — systole, diastole — between sympathy and

antipathy. This alternation is continually within us. Antipathy on the

one hand changes our soul life into picture image: sympathy, which

goes in the other direction, changes our soul life into what we know

as our will for action, into that which holds in germ what after death

is spiritual reality. Here we come to the real understanding of the

life of soul and spirit. We create the seed of the soul life as a

rhythm of sympathy and antipathy.

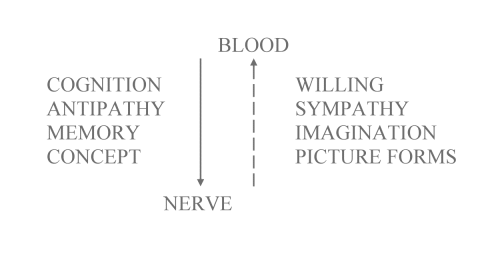

Now what is it that you ray back in antipathy. You ray back the whole

life, the whole world, which you have experienced before birth or

conception. That has in the main the character of cognition. Thus you

really owe your cognition to the shining in, the raying in of your

pre-natal life. And this cognising, which possesses great reality

before birth or conception, is weakened to such a degree through

antipathy that it becomes only a picture image. Thus we can say: this

cognising comes up against antipathy and is thereby reduced to mental

picture.

If antipathy is sufficiently strong something very remarkable happens.

For in ordinary life after birth we could not picture mentally if we

did not do it in a measure with the very force which has remained in

us from the time before birth. When you use this faculty to-day as

physical man you do not do it with a force which is in you, but with a

force which comes from a time before birth, and which still works on

in you. You might suppose it ceased with conception, but it remains

active, and we make our mental pictures with this force which

continues to ray into us. You have it in you, continually living on

from pre-natal times, only you have the force in you to ray it back.

You have this force in your antipathy. When in your present life you

make mental pictures, each such process meets antipathy, and if the

antipathy is sufficiently strong a memory image arises. So that memory

is nothing else but a result of the antipathy that holds sway within

us. Here you have the connection between the purely feeling nature of

antipathy which rays back in an indefinite manner, and the definite

raying back, the raying back of the activity of perception in memory,

an activity which is carried out in a pictorial way. Memory is only

heightened antipathy. You could have no memory if you had so great a

sympathy for your mental pictures that you could devour them; you have

a memory only because you have a kind of “disgust” for them,

you fling them back and in this way make them present. That is their

reality.

When you have gone through this whole process, when you have produced

a mental picture, reflected this back in the memory, and held fast the

image element, then there arises the concept. This then is one side of

the soul's activity: antipathy, which is connected with our pre-natal

life.

Now we will take the other side, that of willing, which is in the

nature of a germ in us and belongs to the life after death. Willing is

present in us because we have sympathy with it, because we have

sympathy with this seed which will not be developed until after death.

Just as our thinking depends upon antipathy, so our willing depends on

sympathy. Now if this sympathy is sufficiently strong— as strong

as the antipathy which enables mental picturing to become memory

— then out of sympathy there arises imagination. Just as memory

arises out of antipathy so imagination arises out of sympathy. And if

your imagination is sufficiently strong (which only happens

unconsciously in ordinary life), if it is so strong that it permeates

your whole being right down into the senses, then you get the ordinary

picture forms* through which you make mental pictures of outer things.

This activity has its starting point in the will. People are very much

mistaken when in speaking psychologically they constantly say:

“We look at things, then we make them abstract, and thus we get

the mental picture.” This is not the case. The fact that chalk is

white to us is a result of the application of the will, which by way

of sympathy and imagination has become picture form.* But when we form

a concept, on the other hand, it has quite a different origin; for the

concept arises from memory.

Here I have described to you the soul processes. It is impossible for

you to comprehend the being of man unless you understand the

difference between the elements of sympathy and antipathy in man.

These elements, as I have described, find their full expression in the

soul world after death. There sympathy and antipathy hold sway

undisguised. I have been describing the soul-man who, on the physical

plane, is united with the bodily man. Everything pertaining to the

soul is expressed and revealed in the body, so that on the one hand we

find revealed in the body what is expressed in antipathy, memory and

concept. All this is bound up with the nerves in the bodily

organisation. While the nervous system is being formed in the body all

that belongs to the pre-natal life is at work there. The pre-natal

life of the soul works into the human body through antipathy, memory

and concept, and hereby creates the nerves. This is the true concept

of nerves. All talk of classifying nerves as sensory and motor is

meaningless, as I have often explained to you.

Similarly, in a certain sense, the activity of willing, sympathy,

picture-forming and imagination works out of the human being. This is

bound to the seed condition; it can never really come to completion

but must perish at the moment it arises; it has to remain as a seed,

and the seed must not evolve too far. Thus it must perish in the

moment of arising. Here we come to a very important fact about the

human being. You must learn to understand the whole man, spirit, soul

and body. Now in man there is something continually being formed which

always has the tendency to become spiritual. But because out of our

great love, albeit selfish love, we want to hold it fast in the body,

it never can become spiritual; it loses itself in its bodily nature.

We have something within us which is material but which is always

wanting to pass over from its material condition and become spiritual.

We do not let it become spiritual, and therefore we destroy it in the

very moment when it is striving to become spiritual — I refer to

blood, the opposite of the nerves.

Blood is really a “very special fluid.” For it is the fluid

which would whirl away as spirit if we were able to remove it from the

human body so that it still remained blood and was not destroyed by

other physical agencies — an impossibility while it is bound to

earthly conditions. Blood has to be destroyed in order that it may not

whirl away as spirit, in order that we may retain it within us as long

as we are on the earth, up to the moment of death. For this reason we

have perpetually within us: formation of blood — destruction of

blood — formation of blood — destruction of blood: through

in-breathing and out-breathing.

We have a polaric process within us. We have those processes within us

which, working through the blood and blood-vessels, continually have

the tendency to lead our being out into the spiritual. To talk of

motor nerves, as has become customary, does not correspond to the

facts, because the motor-nerves would really be blood-vessels. In

contrast to the blood all nerves are so constituted that they are

constantly in the process of dying, of becoming materialised. What

lies along the nerve-paths is really extruded, rejected material.

Blood wants to become ever more spiritual — nerve ever more

material. Herein consists the polaric contrast. In the later lectures

we shall follow these fundamental principles further and we shall see

how this can give us help to arrange our teaching in a hygienic way,

so that we can lead a child to health of soul and body, and not to

decadence of spirit and soul. The amount of bad education now

prevalent is because so much is unknown. Although physiology believes

it has discovered a truth when it talks of sensory and motor nerves,

it is nevertheless only playing with words. Motor nerves are spoken of

because of the fact that when certain nerves are injured, i.e. those

which go to the legs, a man cannot walk when he wants to do so. It is

said that he cannot walk because he has injured the nerves which, as

motor nerves, set the leg in motion. In reality the reason why he

cannot walk is that he has no perception of his own legs. This age in

which we live has been obliged to entangle itself in a mass of errors,

so that, through having to disentangle ourselves from them, we may

become independent human beings.

Now you will have seen, from what I have here developed, that really

the human being can only be understood in connection with the cosmos.

For when we make mental pictures we have what is cosmic within us. We

were in the cosmos before we were born, and our experience there is

now mirrored in us; we shall be in the cosmos again when we have

passed through the gate of death, and our future life is expressed in

seed form in what rules our will. What works unconsciously in us works

in full consciousness for higher knowledge in the cosmos.

We have a threefold expression of this sympathy and antipathy revealed

in our physical body. We have, as it were, three centres where

sympathy and antipathy interplay. First we have a centre of this kind

in the head, in the working together of blood and nerves, whereby

memory arises. At every point where the activity of the nerves is

broken off, at every point where there is a gap, there is a centre

where sympathy and antipathy interplay. Another gap of this kind is to

be found in the spinal marrow; for instance, when one nerve passes in

towards the posterior horn of the spinal marrow and another passes out

from the anterior horn. And again there is such a gap in the little

bundles of ganglia, which are embedded in the sympathetic nerves. We

are by no means such simple beings as it might seem. In three parts of

our organism, in the head, in the chest and in the lower body, there

are boundaries at which antipathy and sympathy meet. In perceiving and

willing it is not that something leads round from a sensory to a motor

nerve, but a direct stream springs over from one nerve to another, and

through this the soul in us is touched; in the brain and in the spinal

marrow. At these places where the nerves are interrupted we unite

ourselves with our sympathy and antipathy to the soul-life; and we do

so again where the ganglia systems are developed in the sympathetic

nervous system.

We are united with our experience with the cosmos. Just as we develop

activities which have to be continued in the cosmos, so does the

cosmos constantly develop with us the activity of antipathy and

sympathy. When we look upon ourselves as men, then we see ourselves as

the result of the sympathies and the antipathies of the cosmos. We

develop antipathy from out of ourselves, the cosmos develops antipathy

together with us; we develop sympathy, the cosmos develops sympathy

with us.

Now as human beings we are manifestly divided into the head system,

the chest system, and the digestive system with the limbs. But please

notice that this division into organised systems can very easily be

combated, because when men make systems to-day they want to have the

separate parts neatly arranged side by side. If we say that a man is

divided into a head system, chest system, and a system of the lower

body with the limbs, then people expect each of these systems to have

a fixed boundary. People want to draw lines where they divide, and

that cannot be done when dealing with realities. In the head we are

principally head, but the whole human being is head, only what is

outside the head is not principally head. For though the actual sense

organs are in the head, we have the sense of touch and the sense of

warmth over the whole body. Thus in that we feel warmth we are head

all over. In the head only are we principally head, but we are

secondarily head in the rest of the body. Thus the parts are

intermingled, and we are not so simply divided as the pedants would

have us be. The head extends everywhere, only it is specially

developed in the head proper. The same is true of the chest. Chest is

the real chest but only principally, for again the whole man is chest.

For the head is also to some extent chest as is the lower body with

the limbs. The different parts are intermingled. And it is just the

same in the lower body. Some physiologists have noticed that the head

is “lower body.” For the very fine development of the

head-nerve system does not really lie within the outer brain layer of

which we are so proud; it does not lie within but below the outer

layer of the brain. For the outer covering of the brain is, to some

extent, a retrogression; this wonderful artistic structure is already

on the retrograde path; it is much more a system of nourishment. So

that in a manner of speaking, we may say a man has no need to be so

conceited about the outer brain for it is a retrogression of the

complicated brain into a brain more used for nourishment. We have the

outer layer so that the nerves which are connected with knowing may be

properly supplied with nourishment. And the reason that our brain

excels the animal brain is only that we supply our brain nerves better

with nourishment. We are only able to develop our higher powers of

cognition because we are able to nourish our brain nerves better than

the animals are able to do. Actually the brain and the nervous system

have nothing to do with real cognition but only with the expression of

cognition in the physical organism.

Now the question is: why have we the contrast between the head system

(we will leave the middle system out of account for the present) and

the polaric limb system with the lower body? We have this contrast

because at a certain moment the head system is breathed out by the

cosmos. Man has the form of his head by reason of the antipathy of the

cosmos. When the cosmos has such aversion for what man bears within

him that it pushes it out, then the image or copy arises. In the head

man really bears the copy of the cosmos in him. The roundly formed

head is such a copy. The cosmos, through antipathy, creates a copy of

itself outside itself. That is our head. We can use our head as an

organ for freedom because it has been pushed out by the cosmos. We do

not regard the head correctly if we think of it as incorporated in the

cosmos as intensively as is our limb-masses system, in which are

included the sexual organs. Our limb system is incorporated in the

cosmos and the cosmos attracts it, has sympathy with it, just as it

has antipathy towards the head. In the head our antipathy meets the

antipathy of the cosmos; there they come into collision. And in the

rebounding of our antipathies upon those of the cosmos our perceptions

arise. All inner life which rises on the other side of man's being has

its origin in the loving sympathetic embrace between the cosmos and

the limb system of man.

Thus the human bodily form expresses how a man, even in his soul

nature, is formed out of the cosmos, and also what he then takes from

the cosmos. If you look at it from this point of view you will more

easily see that there is a great difference between the formation of

the mental picture and the formation of will. If you work exclusively

and one-sidedly on the building up of the former, then you really

point the child back to his pre-natal existence, and you will harm him

if you are educating him rationalistically, because you are coercing

his will into what he has already done with — the pre-natal life.

You must not introduce too many abstract concepts into what you bring

to the child. You must rather introduce imaginative pictures. Why is

this? Imaginative pictures stem from picture-forming and sympathy.

Concepts, abstract concepts, are abstractions; they go through memory

and antipathy, and they stem from the pre-natal life. If you use many

abstractions in teaching a child, you involve him too intensely in the

production of carbonic acid in the blood, namely in processes of the

hardening of the body, and decay. If you bring to the child as many

imaginations as possible, if you educate him as much as possible by

speaking to him in images, then you are actually laying in the child

the germ for the preservation of oxygen, for continuous growth,

because you point to the future, to what comes after death. In

educating we take up again in some measure the activities which were

carried out with us men before birth. We must realise that mental

picturing is an activity connected with images, originating in what we

have experienced before birth or conception. The spiritual Powers have

so dealt with us that they have planted within us this image activity

which works on in us after birth, If in our education we ourselves

give the children images we are taking up this cosmic activity again.

We plant images in them which can become germs, seeds, because we

plant them into a bodily activity. Therefore, whilst as educators we

acquire the power to work in images we must continually have the

feeling: you are working on the whole man; it echoes, as it were,

through the whole human being, if you work in images.

If you yourselves continually feel that in all education you are

supplying a kind of continuation of pre-natal super-sensible activity,

then you will give to all your education the necessary consecration,

for without this consecration it is impossible to educate at all.

To-day we have learnt of two systems of concepts: cognition,

antipathy, memory, concept: willing, sympathy, picture-forming,

imagination: two systems which we shall be able to apply practically

in all that we have to do in our educational work. We will speak

further of this to-morrow.

|