THE TEACHER AS ARTIST IN EDUCATION

The importance for the educator of knowing man as a whole is seen

particularly clearly when we observe the development of boys and girls

between their eleventh and twelfth years. Usually only what we might

call the grosser changes are observed, the grosser metamorphoses of

human nature, and we have no eye for the finer changes. Hence we

believe we can benefit the child simply by thinking: what bodily

movements should the child make to become physically strong P But if

we want to make the child's body strong, capable and free from

cramping repressions we must reach the body during childhood by way of

the soul and spirit.

Between the 11th and 12th year a very great change takes place in the

human being. The rhythmic system — breathing system and system of

blood circulation — is dominant between the change of teeth and

puberty. When the child is nearly ten years old the beat and rhythm of

the blood circulation and breathing system begin to develop and pass

into the muscular system. The muscles become saturate with blood and

the blood pulses through the muscles in intimate response to man's

inner nature — to his own heart. So that between his 9th and 11th

years the human being builds up his own rhythmic system in the way

which corresponds to its inner disposition. When the 11th or 12th year

is reached, then what is within the rhythmic system and muscular

system passes over into the bone system, into the whole skeleton. Up

to the 11th year the bone system is entirely embedded in the muscular

system. It conforms to the muscular system. Between the 11th and 12th

years the skeleton adapts itself to the outer world. A mechanic and

dynamic which is independent of the human being passes into the

skeleton. We must accustom ourselves to treating the skeleton as

though it were an entirely objective thing, not concerned with man.

If you observe children under eleven years old you will see that all

their movements still come out of their inner being. If you observe

children of over 12 years old you will see from the way they step how

they are trying to find their balance, how they are inwardly adapting

themselves to the leverage and balance, to the mechanical nature of

the skeletal system. This means: Between the 11th and 12th year the

soul and spirit nature reaches as far as the bone-.system. Before this

the soul and spirit nature is much more inward. And only now that he

has taken hold on that remotest part of his humanity, the bone-system,

does man's adaptation to the outer world become complete. Only now is

man a true child of the world, only now must he live with the mechanic

and dynamic of the world, only now does he experience what is called

Causality in life. Before his 11th year a human being has in reality

no understanding of cause and effect. He hears the words used. We

think he under-stands them. But he does not, because he is controlling

his bone system from out of his muscular system. Later, after the 12th

year, the bone system, which is adjusting itself to the outer world,

dominates the muscular system, and through it, influences spirit and

soul. And in consequence man now gets an understanding of cause and

effect based on inner experience, — an understanding of force,

and of his own experience of the perpendicular, the horizontal, etc.

For this reason, you see, when we teach the child mineralogy, physics,

chemistry, mechanics before his 11th year in too intellectual a way we

harm his development, for he cannot as yet have a corresponding

experience of the mechanical and dynamical within his whole being.

Neither, before his 11th year can he inwardly participate in thy

causal connections in history.

Now this enlightens us as to how we should treat the soul in children,

before the bone system has awakened. While the child still dwells in

his muscular system, through the intermediary of his blood system, he

can inwardly experience biography; he can always participate when we

bring before him some definite historical picture which can please or

displease him, and with which he can feel sympathy or antipathy. Or

when we give him a picture of the earth in the manner I described

yesterday. He can grasp in picture everything that belongs to the

plant kingdom, because his muscular system is plastic, is inwardly

mobile. Or if we show him what I said of the animal kingdom, and how

it dwells in man — the child can go along with it because his

muscular system is soft. But if before his 11th year we teach the

child the principle of the lever or of the steam engine he can

experience nothing of it inwardly because as yet he has no dynamic or

mechanic in his own body, in his physical nature. When we begin

physics, mechanics and dynamics at the right time with the child,

namely about his 11th or 12th year, what we present to him in thought

goes into his head and it is met by what comes from his inner being,

— the experience the child has of his own bone-system. And what

we say to the child unites with the impulse and experience which comes

from the child's body. Thus there arises, not an abstract,

intellectual understanding, but a psychic understanding, an

understanding in the soul. And it is this we must aim at.

But what of the teacher who has to make this endeavour? What must he

be like? Suppose for example, a teacher knows from his anatomy

and physiology that “the muscle is in that place, the bones here;

the nerve cells look like this”: — it is all very fine, put

it is intellectual; all this leaves the child out of account, the

child is, as it were, impermeable to our vision. The child is like

black coal, untransparent. We know what muscles and nerves are there;

we know all that. But we do not know how the circulation system plays

into the blood system, into the bone-system. To know that, our

conception of the build of a human being, of man's inner configuration

must be that of an artist. And the teacher must be in a position to

experience the child artistically, to see him as an artist would.

Everything within the child must be inwardly mobile to him.

Now, the philosopher will come and say: “Well, if a thing is to

be known it must be logical.” Quite right, but logical after the

manner of a work of art, which can be an inner artistic representation

of the world we have before us. We must accept such an inward artistic

conceiving — we must not dogmatise: The world shall only be

conceived logically. All the teacher's ideas and feelings must be go

mobile that he can realise: If I give the child ideas of dynamics and

mechanics before his 11th year they clog his brain, they congest, and

make the brain hard, so that it develops migraine in the latter years

of youth, and later still will harden; — if I give the child

separate historical pictures or stories before his 11th year, if I

give him pictures of the plant kingdom which shows the plants in

connection with the country-side where they grow, these ideas go into

his brain, but they go in by way of the rest of his nervous system

into his whole body. They unite with the whole body, with the soft

muscular system. I build up lovingly what is at work within the child.

The teacher now sees into the child, what to one who only knows

anatomy and physiology is opaque black coal now becomes transparent.

The teacher sees everything, sees what goes on in the rows of children

facing him at their desks, what goes on in the single child. He does

not need to cogitate and have recourse to some didactic rule or other,

the child himself shows him what needs to be done with it. The child

leans back in his chair when something has been done which is

unsuitable to him; he becomes inattentive. When you do something right

for the child he becomes lively.

Nevertheless one will sometimes have great trouble in controlling the

children's liveliness. You will succeed in controlling it if you

possess a thing not sufficiently appreciated in this connection,

namely humour. The teacher must bring humour into the class

room as he enters the door. Some-times children can be very naughty. A

teacher in the Waldorf School found a class of older children,

children over 12 years old, suddenly become inattentive to the lesson

and begin writing to one another under their desks. Now a teacher

without humour might get cross at this, mightn't he? There would be a

great scene. But what did our Waldorf School teacher do? He went along

with the children, and explained to them the nature of — the

postal service. And the children saw that he understood them. He

entered right into this matter of their mutual correspondence. They

felt slightly ashamed, and order was restored.

The fact is, no art of any kind can be mastered without humour,

especially the art of dealing with human beings. This means that part

of the art of education is the elimination of ill-humour and crossness

from the teachers, and the development of friendliness and a love full

of humour and fantasy for the children, so that the children may not

see portrayed in their teacher the very thing he is forbidding them to

be. On no account must it happen in a class that when a child breaks

out in anger the teacher says: I will beat this anger out of you! That

is a most terrible thing! And he seizes the inkpot and hurls it to the

ground where it smashes. This is not a way to remove anger from a

child. Only when you show the child that his anger is a mere object,

that for you it hardly exists, it is a thing to be treated with

humour, then only will you be acting educationally.

Up till now I have been describing how the human being is to be

understood in general by the teacher or educator. But man is not only

something in general. And even if we can enter into the human being in

such detail that the very activity of the muscular system before the

11th year is transparent to us, and that of the bone system after the

11th year, there will yet remain something else — a thing of

extraordinary vitality where education is an art — namely the

human individuality. Every child is a different being, and what I have

hitherto described only constitutes the very first step in the

artistic comprehension and knowledge of the child.

We must be able to enter more and more into what is personal and

individual. We are helped provisionally by the fact that the children

we have to educate are differentiated according to temperaments. A

true understanding of temperaments has, from the very first, held a

most important place in the education I am here describing, the

education practised at the Waldorf School.

Let us take to begin with the melancholic child; a particular

human type. What is he like? He appears externally a quiet, withdrawn

child. But these outward characteristics are not much help to us. We

only begin to comprehend the child with a disposition to melancholy

when we realise that the melancholic child is most powerfully affected

by its purely bodily, physical nature; when we know that the

melancholy is due to an intense depositing of salt in the organism.

This causes the child of melancholic temperament to feel weighed down

in his physical organism. For a melancholic child to raise a leg or an

arm is quite a different matter than for another child. There are

hindrances, impediments to this raising of the leg or arm. A feeling

of weight opposes the intention of the soul. Thus it gradually comes

about that the child of melancholic disposition turns inward and does

not take to the outside world with any pleasure, because his body

obtrudes upon his attention, because he is so much concerned with his

own body. We only gain the right approach to a melancholic child when

we know how his soul which would soar, and his spirit which would

range are burdened by bodily deposits continuously secreted by the

glands, which permeate his other bodily movements and encumber his

body. We can only help him when we rightly understand this encroaching

heaviness of the body which takes the attention prisoner.

It is often said: Well, a melancholic child broods inwardly, he is

quiet and moves little. And so one purposely urges him to take in

lively ideas. One seeks to heal a thing by its opposite. One's

treatment of the melancholic is to try and enliven him by telling him

all sorts of amusing things. This is a completely false method. We can

never reach the melancholic child in this way.

We must be able, through our sympathy and sympathetic comprehension of

his bodily gravity, to approach the child m the mood which is his own.

Thus we must give him, not lively and, comical ideas, but serious

ideas like those which he produces himself. We must give him many

things which are in harmony with the tone of his own weighted

organism.

Further, in an education such as this, we must have patience; the

effect is not seen from one day to the next, but it takes years. And

the way it works is that when the child is given from outside what he

has within himself he arouses in himself healing powers of resistance.

If we bring him something quite alien, if we bring comic things to a

serious child — he will remain indifferent to the comic things.

But if we confront him outwardly with his own sorrow and trouble and

care he perceives from this outward meeting what he has in himself.

And this calls out the inner action, the opposite. And we heal

pedagogically by following in modern form the ancient golden rule: Not

only can like be known by like, like can be treated and healed by

like.

Now when we consider the child of a more phlegmatic temperament

we must realise: this child of more phlegmatic temperament dwells less

in his physical body and more in what I have called, in my

descriptions here, the etheric body, a more volatile body. He dwells

in his etheric body. It may seem a strange thing to say about the

phlegmatic child that he dwells in his etheric body, but so it is. The

etheric body prevents the processes of man's organic functions, his

digestion, and growth, from coming into his head. It is not in the

power of the phlegmatic child to get ideas of what is going on in his

body. His head becomes inactive. His body becomes ever more and more

active by virtue of the volatile element which tends to scatter his

functions abroad in the world. A phlegmatic child is entirely given up

to the world. He is absorbed into the world. He lives very little in

himself hence he meets what we try to do with him with a certain

indifference. We cannot reach the child because immediate access to

him must be through the' senses. The principle senses are in the head.

The phlegmatic child can make little use of his head. The rest of his

organism functions through interplay with the outer world.

Once again, as in the case of the melancholic child, we can only reach

the phlegmatic child when we can turn ourselves into phlegmatics of

some sort at his side, when we can transpose ourselves, as artists,

into his phlegmatic mood. Then the child has at his side what he is in

himself, and in good time what he has beside him seems too boring.

Even the phlegmatic finds it too boring to have a phlegmatic for a

teacher at his side! And if we have patience we shall presently see

how something lights up in the phlegmatic child if we give him ideas

steeped in phlegma, and tell him phlegmatically of indifferent events.

Now the sanguine child is particularly difficult to handle. The

sanguine child is one in whom the activity of the rhythmic system

predominates in a marked degree. The rhythmic system, which is the

dominant factor between the change of teeth and puberty, exercises too

great a dominion over the sanguine child. Hence the sanguine child

always wants to hasten from impression to impression. His blood

circulation is hampered if the impressions do not change quickly. He

feels inwardly cramped if impressions do not quickly pass and give way

to others. So we can say: The sanguine child feels an inner

constriction when he has to attend long to anything; he feels he

cannot dwell on it, he turns away to quite other thoughts. It is hard

to hold him.

Once more the treatment of the sanguine child is similar to that of

the others: one must not try to heal the sanguine child by forcing him

to dwell a long time on one impression, one must do the opposite. Meet

the sanguine nature, change impressions vigorously and see to it that

the child has to take in impression after impression in rapid

succession. Once again, a reaction will be called into play. And this

cannot fail to take the form of antipathy to the hurrying impressions,

for the system of circulation here dominates entirely. With the result

that the child himself is slowed down.

The choleric child has to be treated in yet a different way.

The characteristic of the choleric child is that he is a stage behind

the normal in his development. This may seem strange. Let us take an

illustration. A normal child of 8 or 9 of any type moves his limbs

quickly or slowly in response to outer impressions. But compare the 8

or 9-year old child with a child of 3 or 4 years. The 3- or 4-year old

child still trips and dances through life, he controls his movements

far less. He still retains something of the baby within him. A baby

does not control its movements at all, it kicks — its mental

powers are not developed. But if tiny babies all had a vigorous mental

development you would find them all to be cholerics. Kicking babies

— and the healthier they are the more they kick — kicking

babies are all choleric. A choleric child comes from a body made

restless by choler.

Now the choleric child still retains something of the rompings and

ragings of a tiny baby. Hence the baby lives on in the choleric child

of 8 or 9, the choleric boy or girl. This is the reason the child is

choleric and we must treat the child by trying gradually to subdue the

“baby” within him.

In the doing of this, humour is essential. For when we confront a real

choleric of 8, 9, 10 years or even older, we shall affect nothing with

him by admonition. But if I get him to re-tell me a story I have told

him, which requires a show of great choler and much pantomime, so that

he feels the baby in himself, this will have

[For further descriptions of the alternation between sympathy

and antipathy in children and its place in education see Steiner's

educational writings passim.]

the effect little by little of calming this “tiny baby.” He

adapts it to the stage of his own mind. And when I act the choleric

towards the choleric child — naturally, of course, with humour

and complete self-control — the choleric child at my side will

grow calmer. When the teacher begins to dance — but please do not

misunderstand me — the raging of the child near him gradually

subsides. But one must avoid having either a red face or a long face

when dealing with a choleric child, one must enter into this inner

raging by means of artistic sensibility. You will see the child will

become quieter and quieter. This utterly subdues the inner raging.

But there must be nothing artificial in all this. If there is anything

forced or inartistic in what the teacher gives the child it will have

no result. The teacher must indeed have artist's blood in him so that

what he enacts in front of the child shall have verisimilitude and can

be accepted unquestioningly; otherwise it is a false thing in the

teacher, and that must not be. The teacher's relation to the child

must be absolutely true and genuine.

Now when we enter into the temperaments in this manner it helps us

also to keep a class in order, even quite a large one. The Waldorf

teacher studies the temperaments of the children confided to him. He

knows: I have melancholies, phlegmatics, sanguines and cholerics. He

places the melancholies together, unobtrusively, without its being

noticed of course. He knows he has them in this corner. Now he places

the cholerics together, he knows he has them in that corner; similarly

with the sanguinis and the phlegmatics. By means of this social

treatment those of like temperament rub each other's corners off

reciprocally. For example the melancholic becomes cheerful when he

sits among melancholies. As for the cholerics, they heal each other

thoroughly, for it is the very best thing to let the cholerics work

off their choler upon one another. If bruises are received, mutually

it has an exceedingly sobering effect. So that by a right social

treatment the — shall we say — hidden relationship between

man and man can be brought into a healthy solution.

And if we have enough sense of humour to send out a boy when he is

overwrought and in a rage — into the garden, and see to it that

he climbs trees and scrambles about until he is colossally tired,

— when he comes in again he will have worked off his choleric

temper on himself and in company with nature. When he has worked off

what is in him by overcoming obstacles, he will come back to us, after

a little while, calmed down.

Now the point is, you see, to come by way of the temperaments into

ever closer and closer touch with the individuality of the child, his

personality. To-day many people say you must educate individually.

Yes, but first you must discover the individual. First you must know

man; next you must know the melancholic — Actually the

melancholic is never a pure melancholic, the temperaments are always

mixed. One temperament is dominant — But only when you rightly

understand the temperament can you find your way to the individuality.

Now this shows you indeed that the art of education is a thing that

must be learned intimately. People to-day do not start criticising a

clock — at least I have not heard it — they do not set up to

criticise the works of a clock. Why? Because they do not understand

it, they do not know the inner working of a clock. Thus you seldom

hear criticism of the working of a clock in ordinary conversation. But

criticism of education — you hear it on all hands. And frequently

it is as though people were to talk of the works of a clock of which

they haven't the slightest inkling. But people do not believe that

education must be intimately learned, and that it is not enough to say

in the abstract: we must educate the individuality. We must erst be

able to find the individuality by going intimately through a knowledge

of man and a knowledge of the different dispositions and temperaments.

Then gradually we shall draw near to what is entirely individual in

man. And this must become a principle of life, particularly for the

artist teacher or educator.

Everything depends upon the contact between teacher and child being

permeated by an artistic element. This will bring it about that much

that a teacher has to do at any moment with an individual child comes

to him intuitively, almost instinctively. Let us take a concrete

illustration for the sake of clarity. Suppose we find difficulty in

educating a certain child because all the images we bring to him, the

impressions we seek to arouse, the ideas we would impart, set up so

strong a circulation in his head system and cause such a disturbance

to his nervous system that what we give him cannot escape from the

head into the rest of his organism. The physical organism of his head

becomes in a way partially melancholic. The child finds it difficult

to lead over what he sees, feels or otherwise experiences, from his

head to the rest of his organism. What is learned gets stuck, as it

were, in the head. It cannot penetrate down into the rest of the

organism. An artist in educating will instinctively keep such a thing

in view in all his specifically artistic work with the child. If I

have such a child I shall use colours and paint with him in quite a

different way than with other children. Because it is of such

importance, special attention is given to the element of colour in the

Waldorf School from the very beginning. I have already explained the

principle of the painting; but within' the painting lesson one can

treat each child individually. We have an opportunity of working

individually with the child because he has to do everything himself.

Now suppose I have by me such a child as I described. I am taking the

painting lesson. If there is the right artistic contact between

teacher and child — under my guidance this child will produce

quite a different painting from another child.

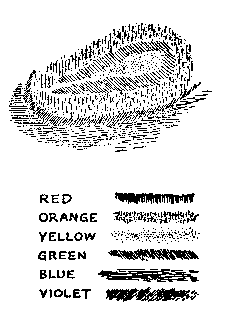

I will draw you roughly on the black-board what should come on the

paper painted on by the child whose ideas are stuck in his head.

Something of this sort should arise:

Click image for large view

Here a spot of this colour (yellow), then further on a spot of some

such colour as this (orange), for we have to keep in mind the harmony

of colours. Next comes a transition (violet), the transition may be

further differentiated, and in order to make an outer limit the whole

may be enclosed with blue. This is what we shall get on the paper of a

child whose ideas are congested in his head.

Now suppose I have another child whose ideas, far from sticking in his

head, sift through his head as through a sieve; where everything goes

into the body, and the child grasps nothing because his head is like a

sieve — it has holes, it lets things through. It sifts everything

down. One must be able to feel that in the case of this child the

circulation system of the other part of the organism wants to suck

everything into itself.

Then instinctively, intuitively, it will occur to one to get the child

to do something quite different. In the case of such a child you will

get something of this sort on the painting paper; You will observe how

much less the colours go into curves, or rounded forms; rather you

will find the colours tend to be drawn out, painting is approximating

to drawing, we get loops which are proper to drawing. You will also

notice that the colours are not much differentiated; here (in the

first drawing) they are strongly differentiated: here in this one they

are very little differentiated.

Click image for large view

If one carries this out with real colours — and not with the

nauseating substance of chalk, which cannot give an idea of the whole

thing — then through the experience of pure colour in the one

case, and of more formed colour in the other, one will be able to work

back upon the characteristics of the child which I described.

Similarly when you go into the gymnasium with a boy or girl whose

ideas stick in his head and will not come out of it, your aim will be

different from that with which yon would go into it with a child whose

head is like a sieve, who lets everything through into the rest of his

body and into the circulation of the rest of his body. You take both

kinds of children into the gymnasium with you. You get the one kind,

— whose heads are like a sieve, where everything falls through

— to alternate their gymnastic exercises with recitation or

singing. The other gymnastic — group — those whose ideas are

stuck fast in their heads — should be got to do their movements

as far as possible in silence. Thus you make a bridge between bodily

training and psychic characteristics from out the very nature of the

child himself. A child which has stockish ideas must be got to do

gymnastics differently from the child whose ideas go through his head

like a sieve.

Such a thing as this shows how enormously important it is to compose

the education as a whole. It is a horrible thing when first the

teacher instructs the children in class and then they are sent off to

the gymnasium — and the gymnastic teacher knows nothing of what

has gone on in class and follows his own scheme in the gymnastic

lesson. The gymnastic lesson must follow absolutely and entirely upon

what one has experienced with the children in class. So that actually

in the Waldorf School the endeavour has been as far as possible to

entrust to one teacher even supplementary lessons in the lower

classes, and certainly everything which concerns the general

development of the human being.

This makes very great demands upon the staff, especially where art

teaching is concerned; it demands, also, the most willing and loving

devotion. But in no other way can we attain a wholesome, healing human

development.

Now, in the following lectures I shall show you on the one hand

certain plastic, painted figures made in the studio at Dornach, so as

to acquaint you better with Eurhythmy — that art of movement which

is so intimately connected with the whole of man. The figures bring

out the colours and forms of eurhythmy and something of its inner

nature. On the other hand I shall speak to-morrow upon the painting

and other artistic work done by the younger and older children in the

Waldorf School.

|