|

LECTURE III.

June

11th, 1924.

The

earthly and cosmic forces of which I have spoken work in the

processes of Agriculture through the substances of the

Earth. And we shall only be able to pass on to the difficult

practical applications during the next few days if we occupy

ourselves rather more closely with the question of how these

forces work through the Earth's substances. But first we must

make a digression and enquire into the activity of Nature

in general.

One

of the most important questions that can be raised in

discussing production in the sphere of Agriculture is

that concerning the significance and influence of nitrogen. But

this question concerning the fundamental nature of the action

of nitrogen is at present in a state of the greatest confusion.

When one observes nitrogen today in the ordinary way one

is only looking at the last offshoots, as it were, of its

activities, its most superficial manifestations. We

overlook the natural interconnections within which

nitrogen is at work; nor indeed can -we help so doing if we

remain enclosed within one section of Nature. To gain a proper

insight into these connections we must bring within our survey

the whole realm of Nature, and concern ourselves with the

activity of nitrogen in the Universe. Indeed — and this

will emerge clearly from my exposition — while nitrogen

as such does not play the primary part in plant-life, it is

nevertheless supremely necessary for us to know what this

part is, if we wish to understand plant-life.

In

its activities in Nature nitrogen has, one might say, four

sister-substances which we must learn to know if we wish to

understand the functions and significance of nitrogen in the

so-called economy of Nature. These four sister-substances are

the four substances which in albumen (protein), both animal and

vegetable, combine with nitrogen in a way which is still a

mystery for present-day science. The four sister-substances are

carbon, oxygen, hydrogen and sulphur. If we wish to understand

the full significance of albumen, it is not enough to mention

the ingredients hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and carbon: we must

also bring in sulphur, that substance the activities of which

are of such profound importance for albumen. For it is sulphur

which acts within the albumen as the mediator between the

spiritual formative element diffused • throughout -the

Universe and the physical element. Indeed, if we want to follow

the path taken by the spirit in the material world, we shall

have to look for the activity of sulphur. Even if this activity

is not so visible as those of other substances it is still of

the utmost importance because spirit works its way into

physical nature by means of sulphur: sulphur is actually the

bearer of spirit. The ancient name “sulphur” is

connected with the word “phosphor,” (which means

bearer of light) because in the old days men saw spirit

spreading out through space in the out-streaming m the light or

the Sun. Hence, they called the substances which are linked up

with the working of light into matter, like sulphur and

phosphorus, the “light bearers.” And once we have

realised how fine (delicate) is the activity of sulphur in the

economy of nature we shall more easily understand its

fundamental nature when we consider the four sister-substances

— carbon. hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen, and the

part they play in the workings of the Universe. The modern

chemist knows very little about these substances. He knows what

they look like in a laboratory, but is ignorant of their inner

significance for cosmic activities as a whole. The

knowledge which modern chemistry has of these substances

is not much greater than the knowledge we might have of a man

whose external appearance we had noticed as he passed us in the

street, and of whom we had perhaps taken a snapshot, whom

we call to mind with the help of the snap-shot. For what

science does with these substances is little more than to take

snap-shots of them, and the books and lectures of to-day about

them contain little more than this. We must learn to know the

deeper essence of these substances.

Let

us therefore start with carbon. The bearing which these things

have upon plants will soon be made clear. Carbon, like so many

beings in modern times, has fallen from a very aristocratic

position to one that is extremely plebeian. All that people see

in carbon nowadays is something with which to heat their

ovens (coal) or something with which to write graphite. Its

aristocratic nature still survives in one of its

modifications, the diamond. But it is hardly of very great

value to us today, in this form, because we cannot buy it.

Thus, what we know of carbon is very little in comparison with

the enormous importance which this substance possesses in the

Universe. And yet, until a relatively recent date, a few

hundred years ago, this black-fellow. — let us call him

so — was regarded as worthy to bear the noble name of

“Philosopher's Stone.”

A

great deal of nonsense has been spoken about what was really

meant by this name. For when the old Alchemists and their

kind spoke of the Philosopher's Stone they meant carbon in

whatever form it occurs. And they only kept their name secret

because if they had not done so, all and sundry would have

found themselves in possession of the Philosopher's Stone. For

it was simply carbon. But why should it have been carbon?

A

-view held in former days will supply us with the answer, which

we must come to know again. If we disregard the crumbled

form to which certain processes in nature have reduced carbon

(as in coal and graphite) and grasp it in its vital activity in

the course of serving the bodies of men and animals and as it

builds up the body of the plant from its own inherent

possibilities, the amorphous and formless substance which we

generally think of as carbon will appear as the final outcome,

the mere corpse of what carbon really is in the economy of

Nature. Carbon is really the bearer of all formative processes

in Nature. It is the great sculptor of form, whether we are

dealing with the plant whose form persists for a certain time

or with the ever-changing form of the animal organism. It bears

within it not only its black substantiality, but, in full

activity and inner mobility it bears within it the formative

cosmic prototypes, the great world-imaginations from which

living form m Nature must proceed. A hidden sculptor is at work

in carbon, and in building up the most diverse forms in Nature,

this hidden sculptor makes use of sulphur. If, therefore, we

regard the activities of carbon in Nature in the right

way, we shall see that the cosmic spirit which is active

as a sculptor “moistens” itself, as it were,

with sulphur, and with the help of carbon builds up the

relatively permanent plant form and also the human form which

is dissolved at the moment it is created. For what makes the

human body human, and not plant-like, is precisely the fact

that at each moment, through the elimination of carbon, the

form it has taken on can be immediately destroyed and replaced

by another, the carbon being united to oxygen and exhaled as

carbon-dioxide. As carbon would make our bodies firm and stiff

like a palm tree, the breathing process wrenches it out of its

stiffness, unites it with oxygen and drives it outwards. Thus,

we gain a mobility which as human beings we must have. In

plants, however (and even in annuals) carbon is held fast

within a fixed form.

There is an old saying that “Blood is a very special

fluid.” We are right in saying that the human ego

pulsates in the blood, and manifests itself physically in

doing so; or speaking more strictly it is along the tracks

provided by the carbon, in its weaving and working, and forming

and unforming of itself that the spiritual principle m man,

called the ego, moves within the blood, moistening itself with

sulphur. And just as the human ego, the essential spirit of

man, lives in carbon, so also does the world-ego live (through

the mediation of sulphur) in that substance that is eyer

forming and unforming itself — carbon. The fact is

that in the early stages of the Earth's development it was

carbon alone which was deposited or precipitated. It was not

until later that, for example, lime came into existence,

supplying man with the foundation for the creation of a

more solid bony structure. In order that the organism which

lives in the carbon might be moved about, man and the higher

animals provided a supporting structure in the skeleton which

is made of lime. In this way, by making mobile the carbon form

within him, man raises himself from the merely immobile mineral

lime formation which the' earth possesses and which he

incorporates in order to have solid earth-matter within his

body. The bony lime structure represents the solid earth within

the human body.

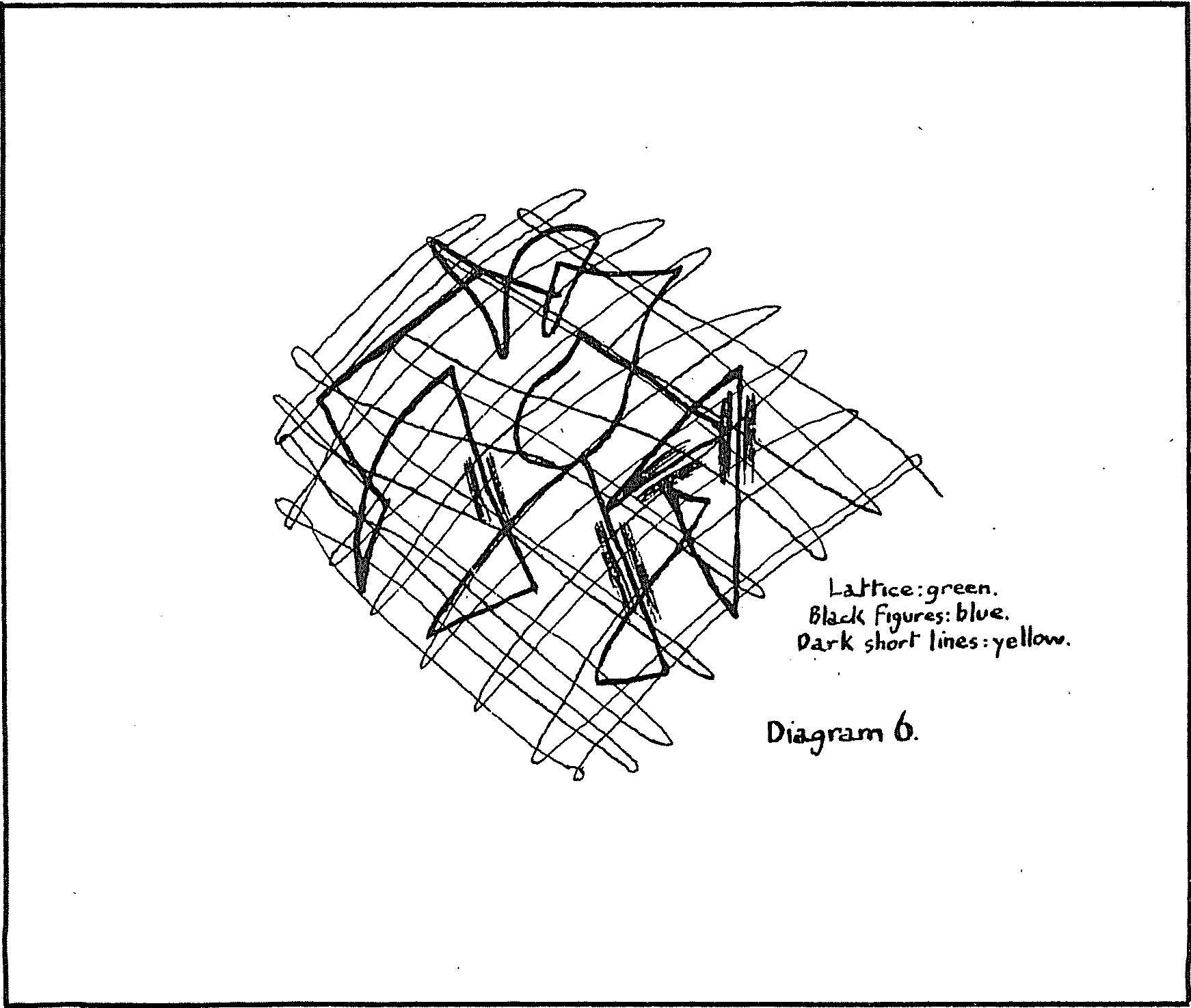

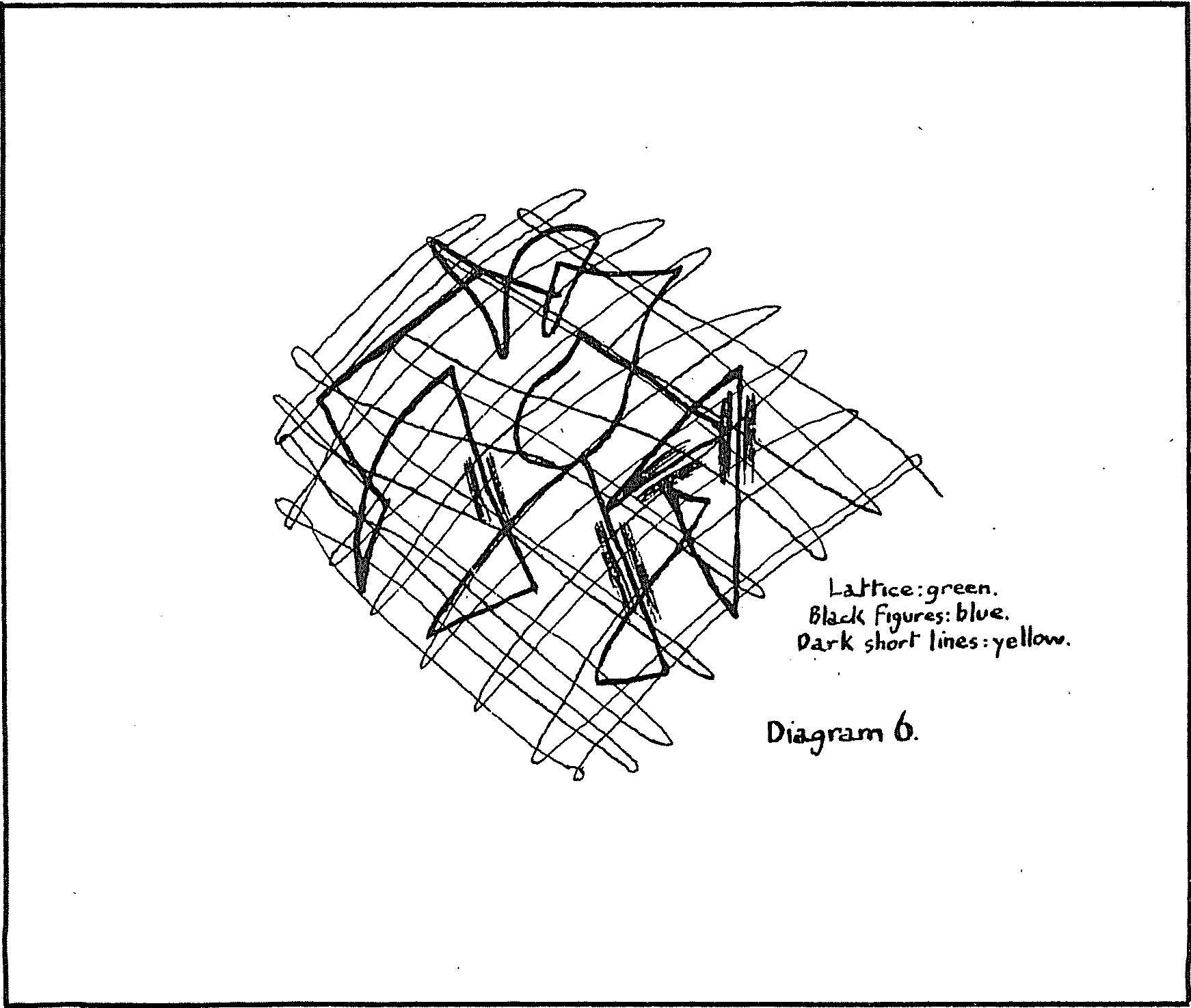

Diagrams

for Lecture II

Let

me put it in this way: Underlying every living being there is a

scaffolding of carbon, more or less either relatively permanent

or continually fluctuating, in the tracks of which the

spiritual principle moves through the world. Let us make a

schematic drawing of this so that you can see the matter quite

clearly before you.

(Drawing No. 6)

Here is such a scaffolding

which the spirit builds up somehow or other with the help of

sulphur. Here we have either the continuously changing carbon

which moves in the sulphur in highly diluted form, or else we

have, as in the plants? a more or less

solidified carbon structure which is united with other

ingredients. Now as I have often pointed out, a human or

any other living being must be penetrated by an etheric

element which is the actual bearer of life. The carbon

structure of a living being must therefore be penetrated by an

etheric element which will either remain stationary about

the timbers of this scaffolding or retain a certain mobility.

But the main thing is that the etheric element is in both cases

distributed along the scaffolding.

This etheric element could not abide our physical earth world,

if it remained alone. It would slide through instead of

gripping what it has to grip in the physical earthly world, if

it were without a physical bearer. (For it is a peculiarity of

earth conditions that the spiritual must always have physical

bearers. The materialists regard the physical bearer

only, and overlook the spiritual. To an extent, they are right,

because it is indeed the physical bearer which is first met

with. But they overlook the fact that it is the spiritual

which makes necessary everywhere the existence of a

physical bearer). The physical Dearer of the spiritual which

works in the etheric element (we may say that the lowest level

of the spiritual works in the etheric); this physical bearer

which is permeated by the etheric element, and

“moistened” as it were with sulphur, introduces

into physical existence not the form, not the structure, but a

continuous mobility and vitality. This physical carrier which,

with the help of sulphur, brings the vital activities out of

the universal ether into the body is oxygen.

Thus, the part which I have coloured green in my sketch can be

regarded, from the physical point of view, as oxygen, and also

as the brooding? vibrating etheric element which

permeates it. It is in the track of oxygen that the etheric

element moves with the help of sulphur.

It

is this that gives meaning to the breathing process. When

we breathe, we take in oxygen. When the present-day materialist

talks of oxygen all he means is the stuff in his test-tube when

he has decomposed water through electrolysis. But in oxygen

there lives the lowest order of the supersensible, the etheric

element; it lives there when it is not killed, as e.g. in the

air around us. In the atmosphere around us the living principle

in the oxygen has “been killed in order that it may not

cause us to faint. Whenever too great a degree of life enters

into us, we faint. For any excess of the ordinary growing

forces within us, if it appears where it should not be, will

cause us to faint or worse. If therefore we were

surrounded by an atmosphere which contained living oxygen, we

should reel about as though completely stunned by it. The

oxygen around us has to be killed. And yet oxygen is from its

birth the bearer of life, of the etheric element. It becomes

the bearer of life as soon as it leaves the sphere in which it

has the task of providing a surrounding for our human external

senses. Once it has entered into us through breathing, it comes

alive again. The oxygen which circulates inside us' is not the

same as that which surrounds us externally. In us it is living

oxygen, just as it also becomes living oxygen immediately it

penetrates into the soil, although in this case the life m it

is lower in degree than it is in our bodies. The oxygen under

the earth is not the same as the oxygen above the earth. It is

very difficult to come to any understanding with physicists and

chemists on this subject, for according to the methods they

employ the oxygen must always be separated with its connection

with the soil. The oxygen they are dealing with is dead, nor

can it be anything else. But every science which limits itself

to the physical is liable to this error. It can only understand

dead corpses. In reality oxygen is the bearer of the living

ether and this living ether takes hold of the oxygen through

the mediation of sulphur.

We

now have pointed out two extreme polarities: On the one hand

the scaffolding of carbon within which the human ego —

the highest form of the spiritual given to us here on earth,

displays its forces or with the case of plants the

world-spiritual which is active in them. On the other hand, we

have the human process of breathing, represented in man by the

living oxygen which carries the ether. And beneath it we have

the scaffolding of carbon which in man permits of his movement.

These two polarities must be brought together. The oxygen

must be enabled to move along the paths marked out for it

by the scaffolding; it must move along every track that may be

marked out for it by the carbon, by tne spirit of carbon; and

throughout Nature the oxygen bearing the etheric life must find

the way to the carbon bearing the spiritual principle. How does

it do this? What here acts as the mediator?

The

mediator is nitrogen. Nitrogen directs the life into the form

which is embodied into the carbon. Wherever nitrogen occurs its

function is to mediate between life and the spiritual element

which has first been incorporated in the carbon

substance. It supplies the bridge between oxygen and

carbon — whether it be the animal and vegetable kingdoms,

or in the soil. That spirituality which with the help of the

sulphur busies itself within the nitrogen is the same as we

usually refer to as astral. This spirituality, which also forms

the human astral body, is active in the earth's surroundings

from which it works in the life of plants, animals and so on.

Thus, spiritually speaking we find the astral element or

principle placed in between oxygen and carbon; but the astral

element uses nitrogen for the purpose of revealing itself in

the physical -world. Wherever there is nitrogen there the

astral spreads forth in activity. The etheric life-element

would float about in every direction like clouds and ignore the

framework provided by the carbon were it not for the powerful

attraction which this framework possesses for nitrogen;

wherever the lines and paths have been laid down in the carbon,

there nitrogen drags the oxygen along; or more strictly

speaking, the astral in the nitrogen drags the etheric element

along these paths. Nitrogen is the great “dragger”

of the living principle towards the spiritual. Nitrogen is

therefore essential to the soul of man, since the soul is the

mediator between life, i.e. without consciousness and spirit.

There is, indeed, something very wonderful about

nitrogen. If we trace its path as it goes through the human

organism, we find a complete double of the human being. Such a

“nitrogen man” actually exists. If we could

separate it from the physical we should have the most beautiful

ghost imaginable, for it copies in exact detail the solid shape

of man. On the other hand, nitrogen flows straight back into

life.

Now

we have an insight into the breathing process. When he

breathes, man takes in oxygen, i.e. etheric life. Then comes

the internal nitrogen, and drags the, oxygen along to wherever

there is carbon, i.e. to wherever there is weaving and changing

form. The nitrogen brings the oxygen along with it in order

that the latter may hold on the carbon and set it free. The

nitrogen is thus the mediator whereby carbon becomes

carbon-dioxide and as such is breathed out. Only a small part,

really of our surroundings consists of nitrogen, the

bearer of astral-spirituality. It is of immense importance to

us to have oxygen in our immediate surroundings, both by day

and by night. We pay less respect to the nitrogen around us in

the air which we breathe because we think we have less need of

it, and yet nitrogen stands in a spiritual relation to

us.

The

following experiment might be made: One could enclose a man in

a gas-chamber containing a given volume of air, and then remove

a small quantity of nitrogen, so that the air would be slightly

poorer in nitrogen than it normally is. If this experiment

could be carefully carried out it would convince you that the

necessary quantity of nitrogen is at once restored, not from

outside, but from inside the man's body. Man has to give up

some of his own supply of nitrogen in order to restore the

quantitative condition to which the nitrogen is

“accustomed.” As human beings, it is necessary that

we should maintain the right quantitative relation between our

whole inner being and the nitrogen around us; the right

quantity of nitrogen outside us is never allowed to become

less. For the merely vegetative life of man a less quantity

than the normal will do. because we do not need nitrogen for

the purpose of breaming. But it would not be adequate to the

part it plays spiritually; for that the normal quantity of

nitrogen is necessary.

This shows you how strongly nitrogen plays into the spiritual

and will give you some idea of how necessary this substance is

to the life of the plants. The plant growing on the ground has

at first only its physical body and etheric body but no astral

body; but the astral element must surround it on all

sides. The plant would not flower if it were not touched from

outside by the astral element. It does not take in the astral

element as do men and the animals but it needs to be touched by

it from outside. The astral element is everywhere, and

nitrogen, the bearer of the astral, is everywhere; it hovers in

the air as a dead element, but the moment it enters into the

soil it comes to life again. Just as oxygen comes to life when

drawn into the soil, so does nitrogen. This nitrogen in the

earth not only comes to life but becomes something which has a

very special importance for Agriculture because —

paradoxical as it may seem to a mind distorted by materialism

— it not only comes to life but becomes sensitive

inside the earth. It literally becomes the carrier of a

mysterious sensitiveness which is poured out over the whole

life of the earth. Nitrogen is that which senses whether the

right quantity or water is present in any given soil and

experiences sympathy; when water is deficient it experiences

antipathy. It experiences sympathy when for any given soil the

right sort of plants are present, and so on. Thus, nitrogen

pours out over everything a living web of sensitive lire. Above

all nitrogen knows all those secrets of which we know nothing

in an ordinary way, of the planets Saturn, Sun, Moon and so on,

and their influences upon the form and life of plants, of which

I told you yesterday, and in the preceding lectures.

Nitrogen that is everywhere abroad, knows these secrets very

well. It is not at all -unconscious of what emanates from the

stars and becomes active in the life of plants and of the

earth. Nitrogen is the mediator which senses just as in the

human nerves and senses system, it also mediates sensation.

Nitrogen is in fact the bearer of sensation. Thus, if we look

upon nitrogen, moving about everywhere like fluctuating

sensations, we shall see into the intimacies of the life in

Nature. Thus, we shall come to the conclusion that in the

handling of nitrogen something is done which is of enormous

importance for the life of plants. We shall study this further

in the subsequent lectures.

In

the meantime, there is, however, one thing more to be

considered. There is a living co-operation of the spiritual

principle which has taken shape within the carbonic

framework with the astral principle working within nitrogen,

which permeates that framework with lire and sensations, that

is, stirs up a living agility in the oxygen. But in the earthly

sphere this co-operation is brought about by yet another

element, which links up the physical world with the expanses of

the cosmos. For the earth cannot wander about the Universe as a

solid entity cut off from the rest of the Universe. If the

earth did this it would be in the same position as a man who

lived on a farm, but wished to remain independent of everything

that grew in the fields around him. No reasonable man would do

that. What to-day is growing in the fields around us tomorrow

will be in human stomachs, and later will return to the soil in

some form or another. We human beings cannot isolate ourselves

from our environment. We are bound up with it and belong

to it as much as my little finger belongs to me. There must be

a continuous interchange of substances, and this applies

also to the relation between earth with all its creatures and

the surrounding Cosmos. All that is living on earth in physical

shape must be able to find its way back into the Cosmos where

it will be in a way purified and refined. This leads us to the

following picture.

(Drawing No. 6)

We

have in the first place the carbon framework (which I have

coloured blue in the drawing), then the etheric oxygenous

life-element (coloured green) and then, proceeding from

the oxygen and enabled by nitrogen to follow the various lines

and paths within the framework, we have the astral element

which forms the bridge between carbon and oxygen. I could

indicate everywhere here how the nitrogen drags into the blue

lines which I have indicated schematically with the green

lines. But the whole of the very delicate structure which

is formed in the living being must be able to disappear again.

It is not the spirit which disappears, but that which the

spirit has built up in the carbon and into which it has drawn

the etheric life borne in the oxygen. It must disappear not

only from the earth, but dissipate into the Cosmos. This is

done by forming a substance which is allied as closely as

possible to the physical, and yet is allied as closely as

possible to the spiritual; This substance is hydrogen. Although

hydrogen is itself the most attenuated form of the physical

substance, it goes still further and dissipates physical

matter which, borne by sulphur, floats away into that

cosmic region in which matter is no longer

distinguishable. One may say then: Spirit has first become

physical and lives in the body at once in its astral form and

reflecting itself as ego. There it lives physically as

spirit transformed into something physical. After a time, the

spirit begins to feel ill at ease. It wishes to get rid of its

physical form. Moistening itself once again with sulphur it

feels the need of yet another element by means of which it can

yield up any kind of individual structure and give itself over

to the cosmic region of formless chaos where there is no longer

any determinate organisation. This element, which is so

closely allied both to the physical and to the spiritual, is

hydrogen. Hydrogen carries away all that the astral principle

Has taken up as form and life, carries it out into the expanses

of the Cosmos, so that it can be taken up again from thence (by

earthly substance) as I have already described. Hydrogen in

fact dissolves everything.

Thus, we have these 5 substances which are the immediate

representatives of all that works and weaves in the realm of

the living and also in the realm of the seemingly dead, which

in fact is only transiently so: Sulphur, Carbon, Hydrogen,

Oxygen and Nitrogen, each of these substances is inwardly

related to its own particular order of spiritual entity.

They are therefore something quite different from which

our modern chemistry refers to by the same names. Our

chemistry speaks only of the corpses of these substances, not

of the actual substances themselves. These we must learn

to know as something living and sentient, and, curiously

enough, hydrogen, which seems the least dense of the five and

has the smallest atomic weight, is the least spiritual

among them.

Now

consider: What are we actually doing -when we meditate? (I am

compelled to add this to ensure that these things do not remain

among the mists of spirituality). The Oriental has meditated in

his own way. “We in Middle and Western Europe meditate in

ours. Meditation as we ought to practise it only slightly

touches the breathing process; our soul is living and weaving

in concentration and meditation. But all these spiritual

exercises have a bodily counterpart, however subtle and

intimate. In meditation, the regular rhythm of breathing, which

is so closely connected with man's life, undergoes a

definite if subtle change. When we meditate we always retain a

little more carbon-dioxide in us than in the ordinary everyday

consciousness. We do not. as in ordinary life, thrust out

the whole bulk of carbon-dioxide into the atmosphere where

nitrogen is everywhere around us. We hold some of it back.

Now

consider: If you knock your head against something hard,

like a table, you become conscious only of your own pain. But

if you gently stroke the surface of the table, then you will

become conscious of the table. The same thing happens in

meditation. It gradually develops an awareness of the nitrogen

all around you. That is the real process in meditation.

Everything becomes an object of knowledge, including the life

of the nitrogen around us. For nitrogen is a very learned

fellow. He teaches us about the doings of Mercury. Venus, etc.

because he knows, or rather senses them. All these things rest

upon perfectly real processes. And as I shall show in greater

detail, it is at this point that the spiritual working in the

soul activity, begins to have a bearing upon Agriculture. This

interaction between the soul-spiritual element and that which

is around us is what has particularly interested our dear

friend Stegemann. For, indeed, if a man has to do with

Agriculture it is a good thing if he is able to meditate,

for in this way he will make himself receptive to the

manifestations of nitrogen. If one does become receptive

in this way, one begins to practise Agriculture in quite a

different way and spirit. One suddenly gets all kinds of new

ideas; they simply come, and one then has many secrets in large

estates and smaller farms.

I

do not wish to repeat what I said an hour ago, but I can

describe it in another way. Take the case ox a peasant who

walks through his fields. The scientist regards him as

unlearned and stupid. But this is not so, simply because

— forgive me but I speak the truth — simply because

instinctively a peasant is given to meditation. He ponders much

throughout the long winter nights. He acquires a kind of

spiritual knowledge, as it were, only he cannot express it.. He

walks through his fields and suddenly he knows something; later

he tries it out. At any rate this is what I found over and over

again in my youth when I lived among peasant folk. The mere

intellect will not be enough, it does not lead us deep enough.

For after all Nature's life and weaving is so fine and

delicate that the net of intellectual concepts —

and this is where science has erred of recent years — has

too large a mesh to catch it.

Now

all these substances of which I have spoken, Sulphur, Carbon,

Nitrogen, Hydrogen are united in albumen. This will enable us

to see more clearly into the nature of seed formation. Whenever

carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen are present in leaf, blossom,

calyx or root they are always united to other substances

in some form or other. They are dependent upon these other

substances. There are only two ways in which they can become

independent. One is when the hydrogen carries all individual

substances out into the expanses of the Cosmos and dissolves

them into the general chaos; and the other is when the hydrogen

drives the basic element of the protein (for albumen) into the

seed formation and there makes them independent of each other

so that they become receptive of the influences of the Cosmos.

In the tiny seed, there is chaos, and in the wide periphery of

the Cosmos there is another chaos, and whenever the chaos at

the periphery works upon the chaos within the seed, new life

comes into being.

Now

look how these so-called substances, which are really bearers

of spirit, work in the realm of Nature. Again, we may say that

the oxygen and nitrogen inside man's body behave themselves, in

an ordinary way, for within man's body they manifest their

normal qualities. Ordinary science ignores it, because the

process is hidden. But the ultimate products of carbon and

hydrogen cannot behave in so normal a fashion as do oxygen and

nitrogen. Let us take carbon first. When the carbon, active in

the plant realm enters the realms of animals and man, it must

become mobile — at least transiently. And in order to

build up the fixed shape of the organism it must attach itself

to an underlying framework. This is provided on the one hand by

our deeply laid skeleton consisting of limestone, and on the

other hand by the siliceous-element which we always carry

in our bodies; so that both in man and in the animals carbon to

a certain extent masks its own formative force. It climbs

up. as it were, along the lines of formative forces of

limestone and silicon. Limestone endows it with the

earthly formative power, silicon with the cosmic. In man and

the animals carbon does not, as it were, claim sole authority

for itself, but adheres to what is formed by lime and

silicon.

But

lime and silicon are also the basis of the growth of plants. We

must therefore learn to know the activities of carbon in the

breathing, digestive and circulatory processes of man in

relation to his bony and siliceous structure — as though

we could, as it were, creep into the body and see how the

formative force of carbon in the circulation radiates into the

limestone and silicon. And we must unfold this same kind of

vision when we look upon a piece of ground covered with flowers

having limestone and silicon beneath them. Into man we cannot

creep; but here at any rate we can see what is going on. Here

we can develop the necessary knowledge. We can see how the

oxygen element is caught up by the nitrogen element and carried

down into the carbon element, but only in so far as the latter

adheres to the lime and silicon structure. We can even say that

carbon is only the mediator. Or we can say that what lives in

the environment is kindled to life in oxygen and must be

carried into the earth by means of nitrogen, where it can

follow the form provided by the limestone and silicon. Those

who have any sensitiveness for these things can observe

this process at work most wonderfully in all

papilionaceous plants (Leguminosae), that is, m all the

plants which in Agriculture may be called collectors of

nitrogen, and whose special function it is to attract nitrogen

and hand it on to what lies below them. For down in the earth

under those leguminosae there is something that thirsts for

nitrogen as the lungs of man thirst for oxygen — and that

is lime. It is ä necessity for the lime under the earth

that it should breathe in nitrogen just as the human lungs need

oxygen. And in the papilionaceous plants a process takes place

similar to that which is carried out. By the

epitheliumfissue in our lungs lining the bronchial tubes. There

is a kind of in-breathing which leads nitrogen down. And these

are the only plants that do this. All other plants are closer

to exhalation. Thus, the whole organism of the plant-world is

divided into two when we look at the nitrogen-breathing.

All papilionacae are, as it were., the air passages. Other

plants represent the other organs in which breaching goes in a

more secret way and whose real task is to fulfil some function.

We must learn to look upon each species of plant as placed

within a great whole, the organism of the plant-world, just as

each human organ is placed within the whole human organism. We

must come to regard the different plants as part of a

great whole, then we shall see the immense importance of these

Papilionacae. True, science knows something of this already,

but it is necessary that we should gam knowledge of them

from these spiritual foundations, otherwise there is a danger,

as tradition fades more and more during the decades, that we

shall stray into false paths in applying scientific

knowledge. We can see how these papilionacae actually

function. They have all the characteristics of keeping

their fruit process which in other plants tends to be higher up

in the region of their leaves. They all want to bear fruit

before they have flowered. The reason is that these plants

develop the process allied to nitrogen far nearer to the earth

{they actually carry nitrogen down into the soil) than do the

other plants, which unfold this process at a greater distance

from the surface of the earth. These plants have also the

tendency to colour their leaves, not with the ordinary green,

hut with a rather darker shade. The actual fruit, moreover,

undergoes a kind of atrophy, the seed remains capable of

germinating for a short time only and then becomes barren.

Indeed, these plants are so organised as to bring to special

perfection what the plant-world receives from Winter and not

from Summer. They have, therefore, a tendency to wait for

Winter. They want to wait with what they are developing for the

Winter. Their growth is delayed when they have a sufficient

supply of what they need, namely, nitrogen from the air which

they can convey below in their own manner. In this way

one can get insight into the becoming and living which goes in

and above the soil.

If

in addition you take into account the fact that lime has a

wonderful relationship with the world of human desires, you

will see how alive and organic the whole thing becomes. In its

elemental form as calcium, lime is never at rest; it seeks and

experiences itself; it tries to become quick-lime, i.e. to

unite with oxygen. But even then, it is not content; it longs

to absorb the whole range of metallic acids, even including

bitumen, which is not really a mineral. Hidden in the earth,

lime develops the longing to attract everything to itself. It

develops in the soil what is almost a desire-nature. It is

possible, if one has the right feeling in these matters,

to sense the difference between it and other substances, lime

fairly sucks one dry. One feels that it has a thoroughly greedy

nature and that wherever it is, it seeks to draw to itself also

the plant-element. For indeed everything that limestone wants

lives in plants, and it must continually turn away from the

lime. What does this? It is done by the supremely aristocratic

element which asks for nothing but relies upon itself. For

there is such an aristocratic substance. It is silicon. People

are mistaken in thinking that silicon is only present where it

shows its firm rock-like outline. Silicon is distributed

everywhere in homeopathic doses. It is at rest and makes no

claim on anything else. Lime lays claim to everything, silicon

to nothing. Silicon thus resembles our sense-organs which do

not perceive themselves but which perceive the external

world. Silicon is the general external sense-organ of the

earth? lime the representing general which desires;

clay mediates between the two. Clay is slightly closer to

silicon, and yet it acts as a mediator with lime. Now one

should understand this in order to acquire a knowledge

supported by feeling. One should feel about lime that it is a

fellow fall of desires, who wants to grab things for

himself; and about silicon that it is a very superior

aristocrat who becomes what the lime has grabbed, carries it up

into the atmosphere, and develops the plant-forms. There dwells

the silicon, either entrenched m his moated castle, as in the

horse-tail (equisetum), or distributed everywhere in fine

homeopathic doses, where he endeavours to take away what the

lime has attached. Once again, we realise that we are in the

presence of an extremely subtle process of Nature.

Carbon is the really formative element in all plants; it builds

up the framework. But in the course of the earth's development

its task has been rendered more difficult. Carbon could

give form to all plants as long as there was water below it.

Then everything would have grown. But since a certain period,

lime has been formed underneath, and lime disturbs the work,

and because the opposition of the limestone had to be overcome,

carbon allies itself to silicon and both together, in

combination with clay, they once again start on their

formative work.

How, in the midst of all this, does the life of a plant go on?

Below is the limestone trying to seize it with its tentacles,

above is the silicon which wants to make it as long and thin as

the tenuous water-plants. But in the midst of them is carbon

which creates the actual plant-forms and brings order into

everything. And just as our astral body brings about a balance

between our ego and etheric body, so nitrogen works in between,

as the astral element.

This is what we must learn to understand — how

nitrogen manages things between lime, clay and silicon,

and also between what the lime is always longing for below, and

what silicon seeks always to radiate upwards. In this way the

practical question arises: What is the correct way of

introducing nitrogen into the plant-world? This is the question

which will occupy us to-morrow and which will lead us over to

deal with the different methods of manuring the ground.

| |

Diagram 4

Click image for large view | |

|