|

LECTURE VIII.

Delivered 16th July, 1924.

In

this last lecture, I shall try as far as possible to complete

what I have already said, and to bring forward certain

practical considerations. In the ensuing discussion, I shall

make such additions as may prove necessary.

The

practical hints I propose to deal with to-day are not such as

can be embodied in general formulae, but need to be greatly

modified according to the particular situation and the

persons applying them. For this very reason, it is necessary

that we should gain Spiritual-Scientific insight into this

sphere, which will enable you intelligently to adapt to

the individual case the various steps to be taken. I would ask

you to consider how little insight there is into that

most important matter, the feeding of our farm animals.

Merely to indicate new methods of feeding is not

sufficient.

How, then, ought our farm animals to be fed? In my opinion,

improvement will certainly come if, in the teaching of

agriculture, an insight is gained into the essential

meaning of feeding as such. This is what I shall try to do

today. Completely wrong ideas prevail as to what nutrition

signifies both for man and beast. It is not merely the crude

process of taking in foodstuffs and after certain changes, of

storing these up in the organism, excreting what is not needed.

This view carries with it the idea, for instance, that the

animal should not be overfed, that its food should be as

nourishing as possible and thus the bulk of it be utilised. And

if we are of a materialistic turn of mind, we like to

distinguish between actual food-stuffs and such

substances as promote what is called combustion in the

organism. We then build up all sorts of theories and put them

into practice, finding, as always, that some work and some do

not? or that they only work for a time, having to be

modified in one way or another.

What else indeed could we expect? We speak of processes

of combustion in the organism. But no such thing takes place

there. The combination of any substance whatever with oxygen in

the organism means something quite different from a process of

combustion. Combustion is a process which takes place in

mineral, inanimate nature, and gust as a living organism is

something different from a quartz crystal, so what is

called “combustion” in a living organism is

not the same as the “dead” process of burning, but

something which is living and even sentient. The mere fact of

using words in this way has directed our thoughts along certain

channels and has done great mischief. To speak of

“combustion” in the organism is to speak in a

slipshod way. This does not matter if, by instinct or

tradition, we still retain a right view of the facts. But if

these slip-shod expressions are subjected to an attack of

“psychopathia Professoralis,” then clever theories

begin to be built upon them. If we depend upon these theories,

what we do will be hopelessly wide of the mark, for such

theories no longer cover the facts of the case. This is

characteristic of our times. We are always doing

something which does not fit in with what is going on in

Nature. In this matter of nourishment, therefore, it is

important to learn with what we are really dealing.

Let

us recall what I said yesterday about the plant as having a

physical and etheric body and being more or less surrounded

from above by the astral element. The plant does not reach the

astral element but is surrounded by it. If the plant enters

into a special relation with the astral element, as in the case

or the formation of edible fruits, a kind of food is produced

which will strengthen the astral element in the animal and

human organism. If one can look into this process, the very

“habitus” of a plant and so on reveals whether or

not it is capable of promoting some process in the animal

organism. But we must also consider the opposite pole.

Here something of great importance takes place. I have

touched on this before, but now that the general

principles of nutrition are being established, I must emphasise

it still more definitely.

Since we are dealing with feeding, let us start from the

animal. In the animal, the threefold organism is not so sharply

defined as it is in man. The animal has a system of nerve and

senses and a metabolic and limb system. These are clearly

divided, the one from the other. But in many animals the limits

of intermediate rhythmic system are indefinite; both nerves and

senses system and metabolic system trespass upon the limits of

the rhythmic system. We should therefore choose other terms

when we speak of animals. In man one is quite right in speaking

of a three-fold organism: but in the case of animals one ought

to speak of the nerve and senses system as being

localised primarily in the head, and of the metabolic and limb

system as being in the hind quarters and limbs but at the same

time diffused throughout the whole body. In the middle of the

body the metabolism becomes more rhythmical as does also the

nervous system, and there both flow into one another. The

rhythmic system has a less independent existence in the animal.

Rather the opposite poles become indistinct as they merge into

one another.

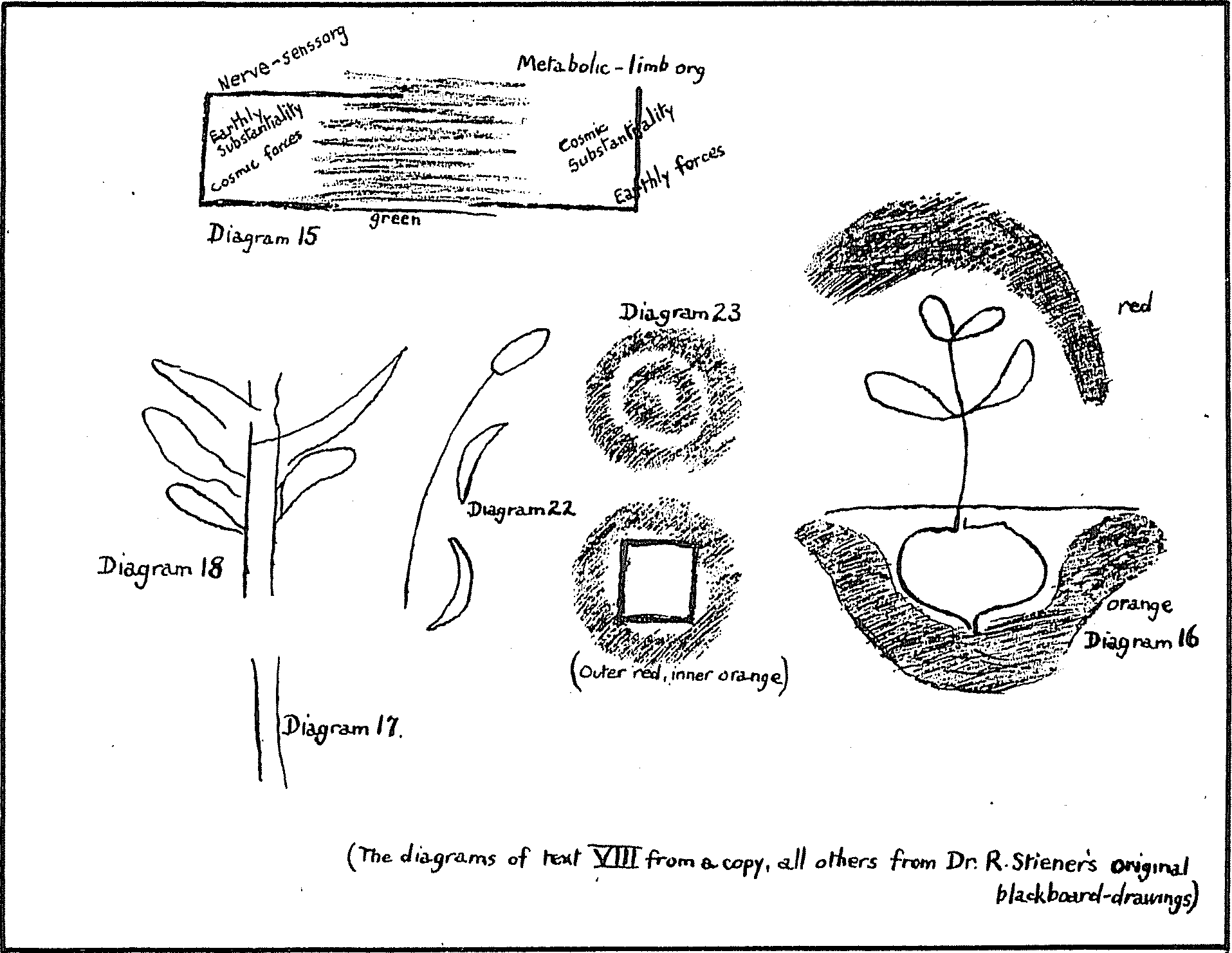

(Drawing 15.)

We should therefore speak of the

animal organism as being twofold, the extremes

interpenetrating at the middle. In this way, the animal

organization arises.

Diagrams

for Lecture VIII

Mow

all the substances contained in the head system — I

am speaking of animals, but the same is true of man — are

of earthly matter. Even in the embryo, earthly matter is led

into the head system. The embryo must be so organised that its

head receives its matter from the earth. In the head,

therefore, we have earthly matter. But the substances which we

bear in the metabolic and limb, organisation, those which

permeate our intestines, our limbs, our muscles and bones,

etc., these substances do not come from the earth, but from

what has been absorbed from the air and warmth above the earth.

It is cosmic substantiality. This is important. “When you

see an animal's claw, you must not think of it as having been

formed by the food which the animal has eaten and which has

gone to the claw and been deposited there. This is not the

case. It is cosmic matter taken up through the senses and the

breathing. What the animal eats serves only to stimulate its

powers of movement so that the cosmic matter can be

driven into the metabolic and limb organisation, can be

driven into the claw and similarly distributed, throughout the

whole organism.

With forces (as opposed to substances) it is the other way

around. Because the senses are centred in the head and take in

impressions from the cosmos, the forces in the head are cosmic

in nature. To understand what happens in the metabolic and limb

organisation, you need only think of walking, which means that

the limbs are permeated with earthly gravity: the forces are

earthly ones. Thus, the limb system contains cosmic substances

permeated by earthly forces.

It

is extremely important that the cow or the ox, if used for

working, should be fed so as to absorb the greatest possible

amount of cosmic substance and that the rood which enters its

stomach should produce the necessary strength to lead this

cosmic substance into its limbs, muscles and “bones. It

is equally important to realise that the (earthly) substances

in the head have to be drawn from the food which has been

worked upon in the stomach and is led into the head. In this

sense, the head relies upon the stomach in a way in which the

big toe does not, and we must realise quite clearly that the

head can only work upon this nourishment which comes to it from

the metabolism, if it can at the same time draw in sufficient

cosmic forces. If, therefore, animals instead of being

left in stuffy stables where no cosmic forces can reach them,

are led into meadows and given every opportunity of entering

into relation with their environment through the perceptions of

their senses, then we may see results such as appear in the

following examples.

Imagine an animal standing in a dark and stuffy stable before

its manger, the contents of which have been measured out by

human “wisdom”„ Unless its diet is varied, as

it only can be out-of-doors, this animal will

show a very great contrast to one which seeks out its food with

its sense of smell, guided by this organ in its search for

cosmic forces, seeking and finding its nourishment by itself

and developing its whole activity in doing so. An animal that

is red from a manger will not show immediately how devoid it is

of cosmic forces, for it has inherited a certain amount of

them. But it will breed descendants to whom these cosmic forces

are no longer transmitted. Such an animal will become weak,

beginning from the head, i.e. it will not be able to nourish

its body because it cannot take in the necessary cosmic

substances which should come in. This will show you that it is

not enough simply to say: “This kind of fodder for one

case, that for another.” Bather one must have a clear

idea of the value for the animal's whole organisation that such

and such methods of feeding have.

But

we must go a step further. What is actually contained in the

head? Earthly substance. If you take out the brain, the noblest

part of an animal, you will have before you a piece of earthly

substance. The human brain also contains earthly substance. But

in both the forces are cosmic. What is the human brain for? It

serves as a support for the ego. The animal, let it be

remembered, has as yet no ego; its brain is only on the way to

ego-formation. In man, it goes on and on to the complete

forming of the ego. How then did the animal's brain come into

existence? Let us look at the whole organic process. All that

which eventually manifests in the brain as earthly matter has

simply been “excreted,” (deposited), from tne

organic process. Earthly matter has been excreted in order to

serve as a base for the ego. Now the process of the working-up

of the food in the digestive tract and metabolic and limb

system produces a certain quantity of earthly matter which is

able to enter into the head and to be finally deposited as

earthly-matter in the brain. But a portion of the food stuff is

eliminated in the intestine before it reaches the brain. This

part cannot be further transformed and is deposited in the

intestine for ultimate excretion.

We

come here upon a parallel which will strike you as being very

paradoxical but which must not be overlooked if we wish

to understand the animal and human organisations. What is brain

matter? It is simply the contents of the intestines brought to

the last stage of completion. Incomplete (premature)

brain-excretion passes out through the intestines. The contents

of the intestines are in their processes closely akin to the

contents of the brain. One could put it somewhat

grotesquely by saying that that which spreads itself out

in the brain is a highly-advanced dung-heap. And yet the

statement is essentially correct. By a peculiar organic

process, dung is transformed into the noble matter of the

brain, there to become the foundation for the development of

the ego. in man the greatest possible quantity of intestinal

dung is transformed into cerebral excrement because man bears

his ego on the earth. In animals, the quantity is less. Hence

there remain more forces in the intestinal excrement of an

animal which we can use for manuring. In animal manure, there

is therefore more of the potential ego element, since the

animal itself does not reach ego-hood. For this reason, animal

dung and human dung are completely different. Animal dung still

contains ego-potentiality. In manuring a plant, we bring this

ego-potentiality into contact with the plant's root. Let us

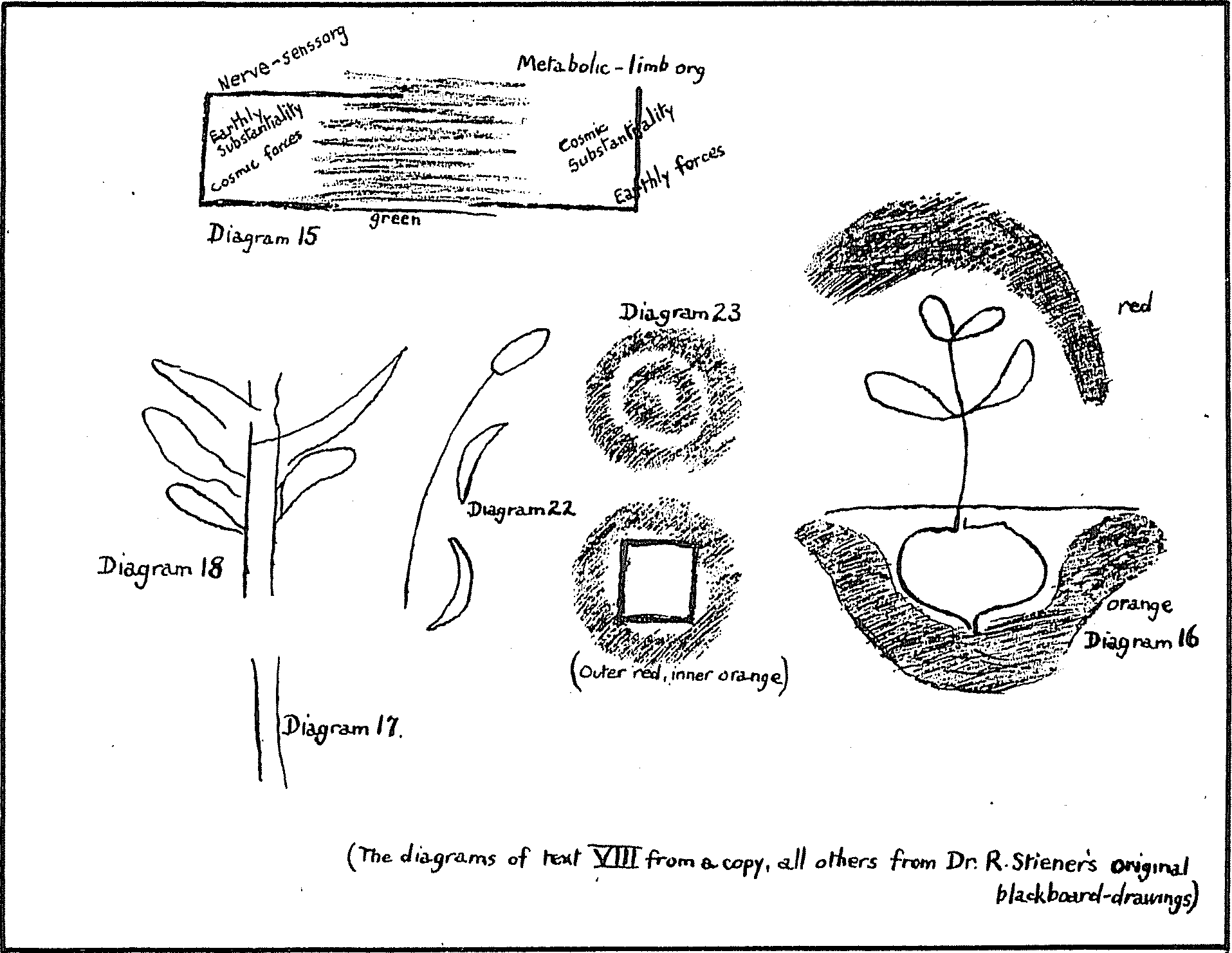

draw the plant in its entirety

(Diagram 16).

Down here you have

the root? up there the unfolding leaves and blossoms. And just

as above, in the leaves and blossoms, the astral element is

acquired from contact with the air, so the ego-potentiality

develops below in the root through contact with the manure.

The

farm is truly an organism. The astral element is developed

above, and the presence of orchard and forest assists in

collecting it. If animals feed in the right way on the things

that grow above the earth, then they will develop the right

ego-potentiality in the manure they produce, and this

ego-potentiality, working on the plant from the root, will

cause it to grow upwards from the root in the right way

according to the forces of gravity. It is a wonderful

interplay, but in order to understand it one must proceed step

by step.

From this you can see that a farm is a kind of

individuality, and that both animals and plants should be

retained within this mutual interplay. If, therefore,

instead of using the manure supplied by the animals

belonging to the farm, we sell off these animals and

obtain manure from Chili, we are in a sense doing harm to

Nature. In doing this we trespass the bounds of that which is a

closed circuit, of that which should be self-sufficient. Of

course, things must be ordered in such a way that the circuit

really is self-contained. One need only have on the farm as

many animals and of such kinds as will supply sufficient and

appropriate manures. And one must also see to it that the

animals have such plants to eat as they like and seek

instinctively.

At

this point experiments tend to become complicated because every

case is different. But the main thing is to know the directions

which the experiments should take. Practical rules will be

found, but they should all proceed from the principle that a

farm should be, as far as possible, self-contained. I say as

far as possible because Spiritual Science takes a practical not

a fanatical view of things. Under our present economic

order this cannot be fully attained; but the ideal is one which

we should make every effort to reach.

On

this basis, then, we can find concrete instances of the

relation between the organism formed by the livestock and

the plant or “fodder organism.” Let us first

consider this relation on broad general lines.

To

begin with the root. The root generally develops in the soil

and through the manure it becomes permeated with

ego-potentiality which it absorbs. This absorption is

determined and aided if the root can find in the right

quantities salts in the soil around it. Let us assume that we

are considering the nature of these roots merely from the point

of view of the foregoing reflections. Then we shall

suggest that roots are the food which, when it is absorbed into

the human organism, will find its way most easily to the head

by way of the digestive process. We shall therefore

provide a diet of roots where we require to give the head

material substances to enable the cosmic forces which

work through the head to exercise their plastic activity. Mow

imagine someone saying to himself: “I must give roots to

this animal which requires earthly substance in its head in

order to stimulate its sense-connections with its

environment, i.e. with the cosmic environment.”

Does not this immediately suggest the calf and the carrot? A

calf eating carrots portrays this whole process. The

moment something like this is put forward and you know how

things really are and their true connections, you will know

immediately what is to be done. It is simply a matter of

realising how this mutual process arises.

But

let us proceed to the next stage. Once the calf has eaten the

carrot, once the substance really has been introduced into the

head, the converse process must be able to begin, i.e. the

head, on its part? must begin to work with forces of

volition, thus begetting within the organism forces which can

be worked into it. It is not enough for the “carrot

dung” to be deposited in the head; from what is deposited

and in the course of disintegration, streams of force

must come which will enter the rest of the organism. In short,

there must be a second food substance which will enable one

part of the body which has already been fed (in this case the

head) to work in the right way on the rest of the organism.

Well, I have given the animal the carrot fodder. And now I want

the animal's body to be permeated with the forces which are

developed from the head. For this, as a second fodder, we need

a plant with a spindly structure, the seed of which will have

gathered into itself these “spindly” forces.

We immediately think of flaxseed (linseed) or something

similar. If you feed young cattle on carrots and linseed

— or carrots and fresh hay (which is equally suitable)

— this will bring into full operation the forces already

latent in the animals. We should therefore try to give young

cattle food which promotes, on the one hand, the forces of

ego-potentiality, and, on the other, the complementary streams

of astral force working from above downwards. For the latter

purpose, those plants are especially suitable which have

long, spindly stems and as such have been turned into hay.

(Diagram 17.)

Just as we have looked into this concrete

case? so we must approach Agriculture as a whole: of

every single thing, we must know what happens to it when it

passes either from the animal into the soil, or from the plant

into the animal.

Let

us pursue the subject yet further. Let us take the case of an

animal' which should become particularly strong in the middle

region (where the head or nervous organisation tends to develop

in the direction of breathing and the metabolic

organisation tends to have a rhythmic character). Which animals

have to be strong in this particular region? They are the milch

animals. The secretion of milk shows that the animal in

question is strong in this region. The point to observe here is

that the right co-operation should take place between the

current going from the head backwards (mainly a streaming of

forces) and the current going from the animal's

hindquarters forward (mainly a streaming of substance).

If these two currents co-operate and intermingle in the right

way, the result will be an abundant supply of rich milk. For

good milk contains substances prepared in the metabolic system

and which, without having entered into the sexual system, have

become akin to it. It.is a sexual process within the metabolic

system. Milk is simply a sexual secretion on another level. It

is a substance, which, on its way to becoming sexual

secretion, is penetrated and transformed by the forces working

from the head. The whole process can be seen quite clearly.

Now

for processes which should arise in this way, we must choose a

diet which will work less powerfully towards the head

than do roots which contain ego-potentiality; neither may

the diet, since it is to be connected with the sexual system,

contain too much of the astral element, i.e. of that which goes

towards the blossom and fruit of the plant. In short, if we

wish to find a diet that will produce milk, we must choose the

part of the plant which lies between blossom and root, i.e. the

green and leafy part.

(Diagram 18.)

If we wish to bring about an

increase in the milk supply of. an animal whose milk production

we have reason to believe could be increased we shall certainly

reach the desired end if we proceed as follows:

Suppose I have a cow and feed it with green fodder. I take

plants in which the process of fruit-formation has been

developed within the process of leaf-formation. Such, for

example, are the pod-bearing or leguminous plants and

especially the clovers. In clover, the would-be fruit develops

as leaf and foliage. A cow that is fed in this way will perhaps

not show much result of it; but when the cow comes to calve,

the calf will grow into a cow that yields good milk. The

effects of reformed foddering usually need a generation in

which to show themselves.

There is however one point to be borne in mind. As we know,

modern doctors go on using certain traditional remedies without

knowing why they do so, except that the remedies have continued

to prove effectual. The same thing happens in farming. People

go on using traditional methods without knowing why they do so,

and m addition to this they make experiments and tests, try to

ascertain exactly the quantity of food that should be given for

fattening cattle, milch cows, etc. But here again we have what

always arises in haphazard experimenting. You know what happens

when you have a sore throat and go and see your friends. They

will all offer you some cure or other and in half-an-hour you

will have collected a whole chemist's shop. If you were to take

all these remedies, they would cancel each other out, and

certainly ruin your stomach, and your sore throat would not be

any better. Because of the circumstances, something which ought

to be quite simple has been made extremely complicated.

Something similar to this happens when one experiments

with fodder for cattle. For it means, does it not, that one is

using a food which suits the case 'in one particular but is

ineffective in another direction. Then a second food is added

to the first and finally one has a mixture of foods, each of

which has a special significance for young cattle perhaps or

for fattening stock. But the whole thing has become so

complicated that one loses one's grasp of it all, because one

loses sight of the interplay of forces involved. Or perhaps the

different ingredients cancel each other in their effects. This

is what often happens and especially with the modern

college-trained student-farmer. Such a person looks things up

in a book or tries to remember what he may have learned

somewhere; “Young cattle must be fed in this way, and

cattle for fattening in that.” But this does not help,

because the fodder recommended by the book may well conflict

with the fodder one i-s already giving.

The

proper way to proceed is to start from the basis of thought

which I have mentioned and which simplifies

cattle-feeding so that it may be taken in at a glance. I really

mean at a glance, as we saw in the case of the carrots and

linseed. We can easily survey this. Think how one can then

stand livingly in the midst of the farm, acting consciously and

with deliberation. This knowledge leads not to a

complication but to a simplification of methods of feeding.

Much that has been discovered by experiment is right, but it is

unsystematic and inexact. Or rather it has the sort of

exactness which is really inexact because things are muddled up

and cannot be seen through. Whereas what I have recommended is

simple and its effects can be followed up into the animal

organism.

Suppose now that we wish to consider the flowering and fruiting

part of the plant. And we must go further, and observe what is

fruit-like in the rest of the plant. This recalls a feature of

plant-life that always delighted Goethe, namely the fact

that the plant has throughout its whole body the tendency

towards what is normally specialised at certain parts. With

most plants, we take the seed which has formed from the blossom

and place it in the earth in order to produce more plants. But

we do not do this in the case of the potato. Here we use the

eyes of the tubers. This is the fruiting part of the potato

plant, but like many processes in Nature, it is not carried out

to the end. We can, however, heighten its activity by a

procedure which bears an external resemblance to combustion.

For instance, if you “cossette” (chop up into thin

straws) roots or tubers and dry the “cossettes” for

fodder, the stuff will be enormously strengthened in its

activity and brought a stage nearer to the fruit stage if you

spread it out in the sun and allow it to steam a little.

Practices like this are based upon a deep and wonderful

instinct. We can ask: how did men first come to cook their

food? Men began to cook their food because they gradually

discovered that what develops during fruit formation is mainly

due to processes akin to cooking, viz. burning, warming, drying

and evaporating. All these processes tend to make the fruit and

seed and indirectly the other parts of the plant,

especially the higher parts, more fitted to develop the forces

that are necessary to the metabolic and limb system in the

animal. Even uncooked the blossom and fruit of a plant work on

the animal's metabolic and digestive system and primarily

through the forces they develop, not through their

substance«, For it is the forces of the earth which are

needed by the metabolic and limb system, and in the

measure in which it needs them, it must receive them.

Take the case of the animals which pasture on steep mountain

sides. Unlike those in the plains, they climb about under

difficult conditions owing to the fact that the ground is not

level. There is all the difference for those animals between

level and slanting ground. They require food that will develop

those forces in limb and muscle which are energised by the

will. Otherwise they would not be good for either labour,

milking or fattening. It is therefore important that they

should eat plenty of those aromatic mountain plants in which

blossom and fruit have undergone an additional treatment

by the sun, resembling a process of natural cooking.

But

similar results can be achieved and strength given to muscle

and limb by artificial methods — roasting and

boiling, etc. Flower and fruit are most suitable for

this, especially of those plants which from the beginning

develop towards fruiting and do not waste their time, as it

were, in growing foliage. People should take careful note of

these things, especially those who are on the dangerous slope

that leads to laziness and inertia. An instance of this is the

man who wants to be a mystic-. “But how,” he asks,

“can I become a mystic if I am working with my

hands all day? I ought to be completely at rest and not be

constantly stirred to activity by something outside or

inside me. If I no longer waste my forces by fussing about all

day, I shall become a real mystic. I must therefore order my

diet in such a way as to become a mystic.” And he goes in

for a diet of raw food and ceases to cook for himself. But the

matter is not so easy as all this. For a man of weak physical

constitution who takes to a diet of raw food when he is

already on the downward path that leads to mysticism, will

naturally accelerate the process; he will become more and more

“mystical” — that is more and more inert',

(and what happens here to a man can be applied to the animal

and can teach us how to stir it to greater) activity). But the

opposite may also occur. We may have the case of a man of

strong constitution who nevertheless has developed the queer

idea of becoming a mystic. In this case his own inherent forces

and those absorbed through the raw food will continue to

develop and to work in him, and the diet may not do him much

harm. And if, by this means, he stirs up the forces which

generally remain below and produce gout and rheumatism

t if” he

stirs these up, and transforms them, then his raw diet will

make mm stronger. There are two sides to every question. No

general rule can be laid down, but we must know how these

principles work in individual cases. The advantage of

vegetarianism is that it calls forth out of the organism forces

which were lying fallow and which produce gout, rheumatism,

diabetes, etc. where only vegetable food is taken, these

forces serve to make it ripe for human assimilation* But where

animal food is consumed, these same forces are deposited

in the organism and remain unused, or rather they begin to work

from out of, themselves, depositing the products of

metabolism in various parts of the body, or, as in diabetes,

they lay claim for their own use to substances which

should remain spread out over all the organs. We only

understand these matters when we look more deeply.

This brings us to the question of the fattening of animals.

Here we must say we should regard the animal as a kind of sack

to be filled as full as possible with cosmic substance. A

fat pig is really a most heavenly animal'. Its fat body,

apart from its system of nerves-and-senses, is made up entirely

of cosmic, not of earthly substance. The pig needs the food

which it enjoys so much in order to fill itself with cosmic

substance, which it absorbs on all sides and then distributes

throughout its body. It must take in this substance which has

to be drawn from the cosmos, and distribute it. And the same is

true of all fattened animals. lou will find that animals will

fatten best on the part of the plant which tends towards

fruit-formation, and has been heightened in its activity by

cooking or steaming. Or, if you give them something which has

in it an enhanced fruit-process, for instance turnip, which

belongs to a species in which this process has been enhanced

and which has become larger through long cultivation. In

general, the best kind of food for fattening cattle is that

which will at least help to distribute the cosmic substance,

i.e. the part of the plant which tends to fruit-formation

— and which has in addition received the proper

treatment. These conditions are in the main fulfilled by

certain kinds of oil cakes and the like. But we must also see

to it that the animal's head is not entirely neglected and that

in this fattening treatment a certain amount of earthly

substance is introduced there. The fodder just mentioned needs

to be complemented by something for the head, though a

smaller quantity, as the head does not require so much.

In fattening an animal, we should therefore add a small

quantity of roots.

Now

there is a substance which as substance has no particular

function in the organism. In general, one can say that roots

have a function in connection with the head, blossoms in

connection with the metabolic and limb system, and leaf and

stem in connection with the rhythmic system within the human

organism. There is, now, a substance that can aid the whole

animal organism, because it is related to all its members. This

substance is salt. And as of all the ingredients in the food of

both man and animals, salt is the least in quantity, we can see

it is not how much we take which matters, but what we take.

Even small quantities of substance will fulfil their purpose if

they are of the right kind.

This brings us to a very important point and one on which I

should like to see very accurate experiments made. These could

be extended to the observation of human beings who use

the article of food I am now going to deal with. As you know,

the introduction of the tomato as a food is of comparatively

recent date. It is very popular as a food and also extremely

valuable as an object of study. One can learn a very great deal

both from growing tomatoes and from eating them. Those who give

the matter some thought — and there are some such

nowadays — are of the opinion and rightly so, that the

consumption of the tomato by man is of great

significance. And it can well be extended to the animal;

it would be quite possible to accustom animals to tomatoes. It

is, in fact, of great significance for all that in the body

which — while in the organism. — tends to fall out

of the organism and to form an organisation of its own« We

have the statement made by an American that in some

circumstances the use of tomatoes can act as a dietetic means

of correcting an unhealthy tendency of the liver. The liver is

the most independent organ in the human organism, and diseases

of the liver (and especially those of the animal liver) can in

general be combated by a diet of tomatoes. Once again, we are

gaining insight into the connection between plant and

animal. Anyone suffering from cancer, I say this in

parenthesis, i.e. from a disease which tends to make one organ

in the body independent from the rest, ought at once to be

forbidden tomatoes.

Why

does the tomato have a special effect upon the parts of the

organism which tend to be independent and specialised in their

function? This is connected with the conditions which the

tomato requires for its own growth. During its growth, the

tomato feels happiest in the vicinity of manure which retains

the form it had when it separated from the animal. Manure

composed of a haphazard collection of all kinds of refuse, not

worked upon in any way, will ensure the growing of very fine

tomatoes. And if compost heaps could be made of tomato stalks

and leaves i.e. of the tomato's own refuse, the result would be

quite brilliant. The tomato does not wish to go beyond its own

boundaries. It would rather remain within its own strong

vitality, it is the most unsocial being in the plant kingdom.

It does not wish to admit anything strange to its own nature

and especially anything which has already been through the

rotting process. And this is connected with the fact that

this plant has a special effect on any independent

organisation within the animal and human bodies.

In

this respect, the tomato bears a certain resemblance to

the potato, also a very independent plant in its effects

— so much so indeed that after passing very easily

through the digestive system, it penetrates into the brain and

makes that organ independent even of the workings of the rest

of the organs'. And among the factors which have led men

and animals to become more materialistic in Europe, we must

certainly reckon the excessive consumption of potatoes. The

consumption of potatoes should serve only to stimulate the

brain and head-system. But it should not go beyond this. These

are the things that show in an objective way the intimate

connection between agriculture and social life. It is

infinitely important that agriculture should be so related to

the social life.

I

have only indicated these matters on general lines and, for

some time to come, these should serve as the foundation for the

most varied experiments, such as should lead to most striking

results. From this you will be able to understand how the

contents of these lectures should be treated. I am thoroughly

in agreement with the decision which has been come to by the

agriculturalists who have attended this course, namely,

that what has been said at these lectures should for the

present remain within this circle and be developed by actual

experiment and research. This same circle should decide when in

their opinion these experiments have been carried

sufficiently far for the matter to be made public. A

number of persons not directly connected with farming, but

whose presence has been permitted through the organisers'

tolerance because of their interest in the subject, nave also

attended this course. They will, like the character in the

well-known opera, be required to put a padlock on their mouths

and not; fall into the common Anthroposophical mistake of

spreading things as far and wide as possible. For what has so

often done us harm is the talk of the individual, dictated not

by a desire to convey real information but simply by a desire

to repeat what has been heard. It makes all the difference

whether these things are said by a farmer or by a layman.

Suppose these things are repeated by laymen as an interesting

new chapter of Anthroposophical teaching. What will happen?

Exactly the same as has happened in the case of other Lecture

Cycles. People on all sides, including farmers, will hear it

... But there are different ways of hearing. A farmer hearing

these things from another farmer will think at first:

“What a pity. The poor fellow has gone crazy.” He

will say this the first and even the second time. But when

finally a farmer sees something with his own eyes, then it is

hardly wise for him to dismiss it as nonsense. But if he has

only heard of a new method from people who are not

professionally concerned with it but only interested in the

subject, then naturally it all comes to nothing and the whole

thing will lose its effect: it will be discredited from the

start. Therefore, those friends who have been present and are

not members of the Agricultural Circle must exercise restraint

and not repeat what' they have heard wherever they go, as

is so often done in Anthroposophy. This course has been decided

on by the Agricultural Circle and the decision announced by our

esteemed Count Keyserlingk, and I entirely agree with it.

And

now that we have come to the end of this Course, I should like

to express my pleasure at your having come to hear what was

said, and at the prospect of your taking part in all the

developments which will take place in the future. I think you

will agree with me when I say that what we have been doing is

useful work, and as such possesses a deep inner value.

There are, however, two things to which I would draw your

attention. The first is the trouble that has been taken by

Count and Countess Keyserlingk and all their household to make

this course the success it has been.

This required energy, self-sacrifice, consciousness of the end

in view, a sense of Anthroposophical values, a real

identification with the cause of Anthroposophy. And this is why

the work we have all been engaged upon, a work which will

undoubtedly be of service to the whole of humanity, has seemed

to take the form of a wonderful festival, for which we give our

heartfelt thanks to Count and Countess Keyserlingk.

| |

Diagram 8

Click image for large view | |

|