![[Steiner e.Lib Icon]](https://wn.rudolfsteinerelib.org/icons/pix/rsa_icon2.gif)

|

|

|

Rudolf Steiner e.Lib

|

|

|

World Economy

Rudolf Steiner e.Lib Document

|

|

|

World Economy

Schmidt Number: S-4906

On-line since: 13th November, 2000

Dornach, 25th July, 1922.

It is precisely in this sphere of Political Economy that the first

conceptions and ideas which we have to develop cannot but be a little

complicated — and for a perfectly genuine reason. For you must

imagine the economic process, considered even as a world-economy, as a

thing of perpetual movement. As the blood flows through the human

being, so do goods, as merchandise or commodities, flow by every

conceivable channel through the whole economic body. And we must

conceive, as the most important thing within this economic process,

all that takes place in buying and selling. That, at least, is true of

the economic life of today. Whatever else there may be — and we

shall of course have to consider the most varied impulses contained in

the economic life — whatever else there may be, the subject of

Economics comes home to a man directly [when/if] he has anything to buy

or sell. In the last resort the instinctive thinking of every naive man

on economic matters culminates in the process taking place between buyer

and seller. Fundamentally, this is what it all comes to.

Consider now: What is it that counts when buying and selling are

considered in the economic process? The thing that a man cares about

will always be the price of a commodity, the price of the piece of

goods concerned. In the last resort all the most important economic

considerations really merge in this question of Price. All the

impulses and forces that are at work in economics culminate at length

in Price. We shall, therefore, first have to consider the problem of

Price, but it is by no means a simple problem. You need only consider

the most simple case: At a given place, A, we have a certain

commodity: at place A it has a certain price. But suppose it is not

bought there but is first transported to another place, B. Our

endeavour will then be to add to the price whatever transport charges

had to be paid from A to B. Thus the Price changes in the process of

circulation. There we have the simplest — if I may put it so, the

flattest — instance: but of course there are far more complex

cases.

Assume, for instance, that at a given date a house in a large town

costs so much. Fifteen years later the same house may perhaps cost six

times as much: nor need we imagine that the main cause of the rise in

price lies in the devaluation of money. On the contrary, let us assume

that this is not the case. The rise in price may simply lie in this:

that in the meantime many other houses have been built around it: the

other buildings, now situated in its neighbourhood, greatly increase

the value of the house. Nay, there may be ten or fifteen other

circumstances accounting for the rise in price. Truth to tell, we are

never in a position to apply some general statement to the single case

— to say, for instance: The price of houses, or railways, or

cereals, can he uniquely determined, at a given place, from certain

specified conditions. To begin with, we can say little more than this:

that we must observe how the price fluctuates with place and time.

Then, perhaps, we can trace some of the conditions whereby at a given

place a given price actually emerges. But there can be no such thing

as a general definition stating how the price of a thing is composed:

that is an impossibility. Again and again one is astonished to find

Price discussed in the ordinary works on Economics, as though it were

possible to define it. We simply cannot define it, for a price is

always concrete and specific. Altogether, in economic matters, it is

impossible to get anywhere near the realities by definitions.

I once witnessed the following case: In a certain district land is

comparatively cheap. There is a Society with a more or less famous man

in its midst. The Society buys up all the cheap plots of land, and

prevails upon the famous man to build himself a house there. Then the

plots of land are offered for sale. They can be offered at a

considerably higher price than they were bought for, for the simple

reason that the famous man has been persuaded to build himself a house

there.

Such instances will show you how indeterminate are the conditions on

which the price of a thing depends in the economic process. Of course,

you may say, such developments must be counteracted. Land reformers

and people with similar aims try to resist these things. Through

various artificial measures they desire to establish a kind of just

price for all things. Of course one can do so: but, economically

considered, the price is not changed thereby. In the above instance,

for example, when the plots of land are sold at a higher price, we can

take the money away again, in the form of a high property-tax. Then

the State will pocket the difference: but the reality remains as

before. In reality the increase in price has taken place just the

same. You can take preventive measures, they will but obscure the

issue. The price will still be what it would have been without them.

You only bring about a redistribution: and it is no true economic

thinking to say that the land has not increased in price during the

last ten years, simply because you have obscured the matter by

artificial measures. Economic Science must stand firmly on its feet,

on a basis of reality. In Economics we can only speak of the

conditions obtaining at a given time and at the actual place to which

we are referring. Needless to say, anyone who desires the progress of

mankind will still come to the conclusion that such and such things

are to be changed. But, to begin with, things must be observed in

their immediate reality at the particular moment. From all this you

will see how impossible it is to approach such a concept as this

— the most important in Economics (I mean the concept of Price)

— by seeking to grasp it with sharply defined notions. In the

science of Economics we can make no progress by this means: quite

other ways must be adopted. We must observe the economic process

itself.

Yet the problem of Price is of cardinal importance: all our efforts

must be directed to this. We must observe the economic process, and

try, as it were, to catch the point where (at any given place and

time) the actual price of a given thing results from all the

underlying economic causes.

Now if you take the ordinary economic doctrines, you will generally

find three factors mentioned — three factors, through the

interplay of which the whole economic process is supposed to take its

course. They are: Nature, human Labour and Capital. It is true that we

can say to begin with: Tracing the economic process we find these

three: that which comes from Nature, that which is achieved by human

Labour and that which is derived from, or directed by means of,

Capital. But if we take Nature, Labour and Capital simply side by side

in this way, we shall not grasp the economic process in a living way.

On the contrary, we shall be led to many one-sided points of view

— a fact to which the history of economic theory bears eloquent

witness. Some say that all Value is inherent in Nature and that no

especial value is added to the substance of natural objects by human

Labour. Others believe that all true economic Value is really

impressed on a piece of goods, on a commodity, by the Labour which, as

they some-times say, is crystallised in the commodity. Or again, the

moment you place Capital and Labour merely side by side, you will find

persons saying on the one hand: In reality it is Capital which alone

makes Labour possible and the wages of Labour are paid out of the

accumulated Capital. On the other side it is said: No, the only thing

that produces real Value is Labour, and all that Capital obtains for

itself is the surplus value abstracted from the yield of Labour.

Ladies and gentlemen, the fact is this: Consider the things from the

one point of view, and the one is right: consider them from the other

point of view, and the other is right. Over against the reality, such

ways of thinking remind one of many a method in book-keeping —

put the item here and this will be the result: put it there, and that

will. One can speak with strong apparent reasons of surplus value,

saying that this is abstracted from the wages of Labour and

appropriated by the capitalist to himself. But one can say with

equally good reasons, that, in the whole connection of economic life,

everything is due in the first place to the capitalist, who can only

pay his workers from what he has available for the wages of Labour.

For both these points of view there are very good and very bad

reasons. In fact, none of these ways of thinking comes near the

reality of economics. Excellent as a basis for agitations, they are of

no importance in a serious economic science. Quite other foundations

must be found if we would hope for progress in economic life.

Up to a certain point, of course, all these systems have their

justification. Adam Smith, for instance, sees the real, original

value-forming factor in the work or labour that is expended on things.

Here again excellent reasons can be brought forward in support of this

view. Such a man as Adam Smith certainly did not think in a stupid or

nonsensical way. Nevertheless, here again there is the underlying idea

of taking hold of something static and giving it a definition, whereas

in the real economic process things are in perpetual movement. It is

comparatively simple to form concepts of the phenomena of Nature

— even the most complicated — as compared with the ideas

which we require for a science of Economics. Infinitely more

complicated, variable and unstable are the phenomena in Economics than

in Nature — more fluctuating, less capable of being grasped with

any defined or hard and fast concepts. In effect, an altogether

different method must be adopted. You will only find this method

difficult in the first lessons: but as a result of it — you will

presently see — we shall discover the only real and possible

foundation for a science of Economics.

To begin with, we may say that to this economic process, which we must

now consider, three things contribute: Nature, human Labour and

(thinking, to begin with, of the purely external economic aspect)

Capital. To begin with, ladies and gentlemen!

But lest us consider at once the middle one of these three, namely,

human Labour. Let us try to form a conception of it by going down, as

I indicated yesterday, into the sphere of animal life. Let us observe,

instead of the economy of peoples, the economy of sparrows, the

economy of swallows.

Here, you see at once, Nature is the basis of economy. True, even the

sparrow has to do a kind of work: at the very least, he must

hop about to find his food. Sometimes he has to hop about a very great

deal in the course of a day to find what he requires. The swallow

building her nest also has to do a kind of work, and she again has

much to do to build it. Nevertheless, in the true economic sense, we

cannot call this “work,” we cannot call it

“Labour.” We shall make no progress in economic ideas if

we call this labour. For if we observe more closely, we shall have to

admit: The sparrow and the swallow are organised precisely in such a

way as to do the very things — fulfil the very functions —

which they fulfil in finding their food, etc. They simply could not be

healthy if they had no opportunity to move about in this way. It is

part and parcel of their organisation: it belongs to them, no less

than their legs and wings. In seeking to build up economic concepts,

we can therefore leave out of account what we might here call a mere

“apparent Labour,” a “semblance of Labour.” In

such cases Nature is taken just as she is, and the single creature,

merely to satisfy its own needs or those of its nearest kin, carries

out the corresponding “semblance of Labour.” If, however,

we wish to determine what is “Value” or “a

Value” in the true economic sense, we must disregard this

apparent Labour. And this must be our first object — to approach

a true concept of “economic value.”

Consider the animal economy once more. There we may say: Nature alone

is the value-forming factor. If we now ascend to man, that is, to

political economy, it is true we still have — from the side of

Nature — the same starting-point of “Nature Value.”

But the moment human beings no longer provide merely for themselves or

for their nearest kindred, but for one another, “human

Labour,” properly so called, comes into account. Indeed, the

moment a man no longer uses the Nature-products for himself, but

stands in some relation to other human beings — if only to the

extent of bartering his goods with theirs — what he then does

becomes, in relation to Nature, “human Labour.” Here we

arrive at the one aspect of Value in Political Economy. It arises

thus: Human Labour is expended on the products of Nature, and we have

before us in economic circulation Nature-products transformed by human

Labour. It is only here that a true economic value first arises. So

long as the Nature-product is untouched, at the place where it is

found in Nature, it has no other value than it has, for instance, for

the animals. But the moment you take the very first steps to put the

Nature-product into the process of economic circulation, the

Nature-product so transformed begins to have economic value. We may

therefore characterise this economic value as follows: “An

economic value, seen from this one aspect, is a Nature-product

transformed by human Labour.” Whether the human Labour consists

in digging or chopping, or merely moving a product of Nature from one

place to another, is irrelevant. If we are seeking the determination

of Value in general, then we must simply say: “One value-forming

factor is human Labour, transforming a Nature-product so as to pass it

into the economic process of circulation.”

If you consider this, you will see at once how very fluctuating is the

value of a piece of goods circulating in the economic life. For Labour

is something always present, perpetually being expended on the goods.

You cannot really say what Value is — you can only say: Value

appears in a given place and at a given time, inasmuch as human Labour

is transforming some product of Nature. That is where Value emerges.

To begin with, we cannot and will not try to define Value: We simply

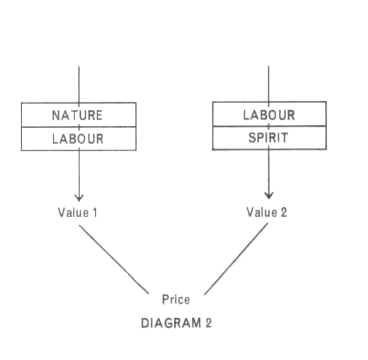

point out the place where it appears. I will put this down

diagrammatically. (see

Diagram 2)

Here on the left side of the drawing we have Nature

as it were in the background. Human Labour approaches Nature: what

then becomes visible — appearing, as it were, through the

interplay of Nature and human Labour — that is the one aspect of

economic value? It is by no means a faulty image if we say, for

instance: Look at a black surface or at anything black through a

luminous medium and you will see it blue. According as the luminous

medium is thick or thin, you will see various shades of blue:

according as you shift it, its density will vary: it is for ever

fluctuating. So it is

with Value in the economic life, it is really none other than the

appearance of Nature through human Labour. And that, too, is always

fluctuating.

To begin with, we are gaining a few abstract indications and little

more: but these will give us our bearings during the next few days and

help us to reach more concrete things. After all, you are accustomed

to this: for in all sciences one takes what is most simple to begin

with.

You see, labour as such has no purpose at all in Economics. A man may

chop wood, or he may get up on to a wheel like this. (There are such

wheels for the benefit of fat people who go on climbing from step to

step; the wheel goes round under them, and so they hope to get

thinner.) The man who treads this wheel may be doing just as much work

as the one who chops wood. To consider Labour as Marx did, when he

said that we should look for its equivalent in the amount that is

consumed in the human organism by the Labour, is a colossal piece of

nonsense. For the same amount is consumed whether a man chops wood or

dances about on this wheel. How much is done in the human being is not

the point in Economics. We have already seen how the subject of

Economics borders on uneconomic matters. Purely economically speaking,

it is quite unjustifiable to point to the fact that Labour uses up the

human being's forces. I mean it is unjustifiable in this connection,

where, to begin with, we wish to establish a concept of Labour in the

sense of Economics. Indirectly it is of great significance, for on the

other side the needs of men have to be cared for. But Marx's way of

thinking at this point is a colossal piece of nonsense.

What do we need in order to take hold of “Labour” in the

economic process? It is necessary, to begin with — quite apart

from the human being — to observe how the Labour enters

into the economic process. This labour (of the man on the wheel) does

not enter it at all: it simply adheres to the man himself. The

chopping of wood, on the other hand, does enter the economic process.

The one thing that matters is: How does the Labour enter the

economic process? The answer is this: Nature is everywhere transformed

by human Labour and only in so far as Nature is transformed by human

Labour do we create real economic values on this one side. If, for

instance, we find it necessary for our bodily health, having worked

upon Nature in some way, to dance a little or to do Eurhythmy in the

intervals, all this may of course be judged from another standpoint:

but what we do in the intervals cannot be described as work or Labour

in the economic sense, nor can it be regarded as in any way a factor

creating economic values. Seen from another side, it may well be

creating values, but we must first get our concepts pure and clear

concerning economic values as such.

Now there is a second, altogether different, possibility for economic

values to arise. It is this: We turn our attention to labour as such:

we take labour as the given thing. To begin with, as you have seen

just now, labour, economically speaking, is some-thing neutral and

irrelevant. But it becomes an economic value-creating factor the

moment we let it be directed by the intelligence of man. I must now

speak in a somewhat different sense from before. Even in the most

far-fetched cases, you can imagine some-thing that would otherwise not

be Labour at all being transformed into real Labour by human

intelligence. If it occurs to a man, in order to get thinner, to set

up that apparatus which we spoke of in his bedroom and practise on it,

there will be no economic value in it. But, if somebody winds a rope

round the wheel and uses it to drive some machine, the moment this is

done, that which would not otherwise be Labour at all, in the economic

sense, is turned to good account by the Spirit. Incidentally the

fellow who treads the wheel will get thinner just the same, but the

essential point is this: Through the Spirit — by intelligence,

reflection, perhaps even speculation — Labour is given a certain

direction: the various units of Labour are brought into certain mutual

relations, and so on.

Thus, we may say: Here we have the second aspect of the value-forming

factors in Economics. Here Labour stands in the background, and before

it is the Spirit which directs the Labour. Labour shines through

the Spirit, and this creates once more an economic value. As you

will soon see, these two aspects are present everywhere. Having shown

in this

diagram (left)

how an economic value emerges when we have

Nature appearing through Labour — if we now wish to represent

diagrammatically what we have just explained, we shall have to put

Labour in the background and in the front of it the spiritual, which

gives it a certain modification (right).

These are the two essential poles of the economic process. There are

indeed no other ways in which economic values are created. Either

Nature is modified by Labour, or Labour is modified by Spirit (human

intelligence). The outer expression of the Spirit, in this connection,

is in the manifold formations of Capital. Economically, the Spirit

must be looked for in the configurations of Capital: these at any rate

are its outward expression. We shall realise the facts more clearly

when we come to consider Capital as such, and then Capital as a

monetary medium.

So you see there can be no question of arriving at a definition of

economic value. Once more you need only consider on how many

circumstances — on the cleverness or stupidity of how many

different people — the modification of Labour by the Spirit in

any given instance will depend. There is every kind of fluctuating

condition. Nevertheless, this fact will always be in evidence: The

value-creating factors in the economic process will always be found at

these two opposite poles.

Suppose now we find ourselves at any given point within the economic

process. The economic process takes its course in the activities of

buying and selling. Buying and selling are essentially an exchange of

values: there is, in fact, no other exchange than that of values.

Properly speaking, it is wrong to speak of an exchange of goods. The

“goods ” that play a part in the economic process —

whether they appear as modified products of Nature or modified Labour

— are always values. It is always the values that are

exchanged. Whenever a process of buying and selling takes place,

values are exchanged. Now what is it that emerges in the economic

process when value and value, as it were, impinge on one another in

the process of exchange? It is Price. Wherever Price emerges, it is

always through the impact of value on value in the economic process.

For this reason you cannot think truly about Price if you have in mind

the exchange of mere goods. If you buy an apple for a penny, you may

say that you are exchanging one piece of goods for another — the

apple for the penny. But you will make no progress in economic

thinking along these lines. For the apple has been picked somewhere

and then transported, and it may well be that various other things

have been done around it. All this is Labour which has modified it.

What you are dealing with is not an apple but a Nature-product

transformed by human Labour, representing an economic value. In

Economics we must always take our start from values. Similarly,

the penny represents not a piece of goods but a value, for after all

(or so at any rate we must suppose) the penny is but the sign for the

fact that there is present, in the man who has to buy the apple,

another value which he exchanges for it.

Today I am anxious for you to get a clear insight into this fact: In

Economics we must not speak of “goods ” but of

“values” as the elementary thing. It is wrong to try to

consider Price in any other way than by envisaging the interplay of

values. Value set against value gives you Price. And if, as we saw,

value itself is a fluctuating thing, incapable of definition, may we

not say that when you exchange value for value, Price which arises in

the process of exchange is a fluctuating thing raised to the second

power?

From all these things you may see how futile it is to try to take hold

of values and prices with the idea of finding a firm and fixed ground

in Economics: and it is still more futile, if your object is to

influence the economic process in practice. Something altogether

different is needful — something that lies behind all these

things. You may see this from a very simple consideration.

Consider this for a moment: Nature appears to us through human Labour.

Suppose we obtain iron at a given place under extraordinarily

difficult conditions. The value that is thus produced through human

Labour is a modified object of Nature. If at a different place iron is

to be produced under far easier conditions, it may happen that an

altogether different value will result. You see, therefore, that we

cannot grasp the reality in the value itself: we must go behind

the value. We must go back to that which creates the value: here alone

can we gradually find our way to the more constant conditions on which

we can exercise a direct influence. The moment you have brought the

value into economic circulation, you must let it fluctuate with the

economic organism as a whole. Consider the finer constitution of a

blood corpuscle: it is different in the head and in the heart and in

the liver. You cannot say: We will now seek the true definition of

blood. The most you can do is to consider what are the more favourable

foodstuffs in the one case and in the other. Likewise there is no

point in talking round and round about Value and Price. The important

thing is to go back to the primary factors, back to that which, if

rightly formed, will actually bring forth the proper price. The proper

price will then emerge of its own accord.

In the study of Economics it is quite impossible to stop short at

definitions of Value and Price. We must always go back to the real

origins whence the economic process is nourished, on the one hand, and

by which, on the other hand, it is regulated — Nature on the one

hand, Spirit on the other.

In all economic theories of modern time, this has been the

difficulty: they have always tried to hold fast at the outset that

which is really fluctuating. As a result, one who can see through

these things finds himself confronted not with wrong

definitions — scarcely any of them are wrong: they are generally

quite right! (Though, it is true, one must make an exceedingly bad

shot to say: The amount of Labour corresponds to that which has been

expended and has to be restored in the human body: it corresponds,

therefore, to the expenditure of substance. Such a statement is really

a howler, and he who makes it has failed to see the simplest things).

No, the point is that even men of considerable insight, in developing

their theory of Economics, have stumbled again and again over this

obstacle: They have tried to observe at rest things that are always in

a state of flux. For the things of Nature one can and must often do

so: there, however, it suffices to observe the state of rest in a

quite different way: and if we have to observe a state of movement,

all we have come to do in the modern science of Nature is to regard it

as though it were composed of a multitude of tiny states of rest and

jump from one to the other. For when we integrate, we regard

even movement as if it were composed of states of rest.

On the model of such a science we cannot study the economic process.

This, therefore, must be said: The first thing needful in grappling

with the science of Economics is to consider how, on the one hand,

Value appears inasmuch as Nature is transformed by human Labour —

Nature is seen through human Labour — while, on the other hand,

Value appears inasmuch as Labour is seen through the Spirit. These two

origins of Value are the real polar opposites: they differ as, in the

spectrum, the one — the luminous or yellow pole — differs

from the other — the blue or violet. You may well hold fast this

picture: As in the spectrum the warm colours appear on the one side,

so on the one side there appears the Nature-value which will show

itself more in the formation of rents. On this side we perceive Nature

transformed by Labour. On the other side there appear to us instead

those values which are translated into Capital: here we see Labour

transformed by the Spirit. Then, indeed, Price can arise, inasmuch as

values of the one pole impinge on values of the other. Or again, the

several values within the one pole come into mutual interaction. The

point is that every time, wherever it is a question of

price-formation, there will be a mutual interaction of value and

value. We must therefore disregard everything to do with the

substances and materials themselves; we must look away from all this

and begin by seeing how values are formed, on the one side and on the

other. Then we shall be able to press forward to the problem of Price.

|

Last Modified: 20-May-2025

|

The Rudolf Steiner e.Lib is maintained by:

The e.Librarian:

elibrarian@elib.com

|

|

|

![[Spacing]](https://wn.rudolfsteinerelib.org/AIcons/images/space_72.gif)

|

|