Lecture III

Dornach

31st July, 1915

The Power of Thought

My dear friends, it is really difficult in our time

to meet with full understanding when one speaks out of the sources of

what we call Spiritual Science.

I have not in mind so much the

difficulty of being understood among the individuals whom we

encounter in life, but much more of being comprehensible to the

cultural streams, the various world-conceptions and feelings which

confront us at the present time.

When we consider European life we find

in the first place a great difficulty which has sprung from the

following cause. European life at the moment of passing over from

mere sense perceptions to thinking about percepts

— and this is effected by every individual in

every moment of his waking life — does not feel

how intimately connected is the thought-content with what we are as

human beings.

People think thoughts, they form

concepts, and they have the consciousness that through these thoughts

and concepts they are, as it were, learning something of the world,

that the images in fact reproduce something of the world. This is the

consciousness people have. Each one who walks along the street has

the feeling that because he sees the trees etc. concepts come to

life, and that the concepts are inner presentations of what he

perceives, and that he thus in some way takes the world of external

percepts into himself and then lives them over again.

In the rarest cases, one can say

practically never, is it brought to consciousness in the European

world-conception that the thought, the act of thinking, is an

actuality in our inner self as man, that we do something by thinking,

that thinking is an inner activity, an inner work.

I called your attention here once to the

fact that every thought is essentially different from what people

usually believe it to be. People take it to be a reproduction of

something perceptible. But it is not recognised as a form-builder, a

moulder. Every thought that arises in us seizes, as it were, upon our

inner life and shares (above all so long as we are growing) in our

whole human construction. It already takes part in our structure

before we are born and belongs to the forming forces of our nature.

It goes on working continually and again and again replaces what dies

away in us. So it is not only the case that we perceive our concepts

externally, but we are always working upon our being through our

thoughts, we work the whole time anew upon our forming and fashioning

through what we conceive in ideas.

Seen with the eyes of spiritual science

every thought appears like a head with a sort of continuation

downwards, so that with every thought we actually insert in us

something like a shadowy outline, a phantom, of ourselves; not

exactly like us, but as similar as a shadow-picture. This phantom of

ourselves must be inserted, for we are continuously losing something,

something is being destroyed, is actually crumbling away. And what

the thought inserts into our human form, preserves us, generally

speaking, until our death. Thought is thus at the same time a

definite inner activity, a working on our own

construction.

The western world-concept has

practically no knowledge of this at all. People do not notice, they

have no inner feeling of how the thought grips them, how it really

spreads itself out in them. Now and again a man will feel in

breathing — though for the most part it is no

longer noticed — that the breath spreads out in

him, and that breathing has something to do with his re-building and

regeneration. This applies also to thoughts, but the European

scarcely feels any longer that the thought is actually striving all

the time to become man, or, better said, to form the human

shape.

But unless we come to a feeling of such

forces within us we can hardly reach a right understanding, based on

inner feeling and life, of what spiritual science really desires. For

spiritual science is actually not active at all in what thought

yields us inasmuch as it reproduces something external; it works in

the life element of thought, in this continuous shaping process of

the thought.

Therefore it has been very difficult for

many centuries to speak of spiritual science or to be understood when

it was spoken of, because this last characterised consciousness

became increasingly lost to European humanity. In the Oriental

world-conception this feeling about thought which I have just

expressed exists in a high degree. At least the consciousness exists

in a high degree that one must seek for this feeling of an inner

experience of thought. Hence comes the inclination of the Oriental

for meditation; for meditation should be a familiarising oneself with

the shaping forces of thought, a becoming aware of the living feeling

of the thought. That the thought accomplishes something in us should

become known to us during meditating. Therefore we find in the Orient

such expressions as: A becoming one, in meditation, with Brahma, with

the fashioning process of the world. What is sought in the Oriental

world-conception is the consciousness that when one rightly lives

into the thought, one not only has something in oneself, not only

thinks, but one becomes at home in the fashioning forces of the

world. But it is rigidified, because the Oriental world-conception

has neglected to acquire an understanding for the Mystery of

Golgotha. To be sure, the Oriental world-conception of which we have

yet to speak — is eminently fitted to become at

home in the forming forces of thought life, but nevertheless in so

doing, it comes into a dying element, into a network of abstract,

unliving conceptions. So that one could say: whereas the right way is

to experience the life of the thought-world, the Oriental

world-conception becomes at home in a reflection of the life of

thought. One should become at home in the thought-world as if one

were transposing oneself into a living being; but there is a

difference between a living being and a reproduction of a living

being, let us say a papier-mâché copy. The

oriental world-conception, whether Brahmanism, Buddhism, the Chinese

and Japanese religions, does not become at home in the living being,

but in something which may be described as a copy of the

thought-world, which is related to the living thought-world, as the

papier-mache organism is related to the living organism.

This then is the difficulty, as well in

the West as in the East. One is less understood in the West, since in

general not much consciousness exists there of these living, forming

forces of thought; in the East one is not understood aright, since

there people have not a genuine consciousness of the living nature of

thought, but only of the dead reproduction, of the stiff, abstract

weaving of thoughts.

Now you must be clear whence all that I

have just analysed actually comes. You will all remember the account

of the Moon evolution given in my bookOccult Science. Man in his own evolution has taken his proper

share in all that has taken place as Saturn, Sun and Moon evolutions,

and he then further shares in what comes about as Earth evolution.

When you call to mind the Moon evolution as described in my Occult

Science you find that during that time the separation of the moon

planet from the sun took place; that it proceeded for the first time

in a distinct, definite way. Thus such a separation actually took

place. We can say that whereas before there had been a kind of

interconnected condition of the planetary world, at the separation of

the moon from the sun there now took their course side by side the

Moon evolution and the Sun evolution. This separate state was of

great significance, as you can gather fromOccult Science. Man as he now is could not have arisen if this

separation had not taken place. But on the other hand, with every

such event is intimately connected the emergence of a certain

one-sidedness. It came about that certain beings of the Hierarchy of

the Angeloi, who were at the human stage during the Moon evolution,

at that time rebelled against, showed themselves in antipathy to,

uniting again with the Sun. Thus the Moon broke away, and at the

later reunion with the Sun they refused to take this step, and be

reunited with the Sun.

All Luciferic staying behind rests upon

an unwillingness to take part in later phases of evolution. And

hence, on the one hand, the Luciferic element originated in the fact

that certain beings from the Hierarchy of the Angeloi, who were human

at that time, were not willing to reunite with the Sun in the last

part of the Old Moon time. To be sure, they were obliged to descend

again, but in their feeling, in their inner nature, they preserved a

longing for the Moon existence. They were out of place, they were not

at home in the existing evolution; they felt themselves to be

actually Moon-beings. Their remaining behind consisted in this. The

host of Luciferic beings who then in their further development

descended upon our Earth naturally contained in their ranks this kind

of being. They also live in us in the manner I have indicated in one

of the last lectures. And it is they who will not let the

consciousness arise, in our Western thinking, that thinking is

inwardly alive. They want to keep it of a Moon-nature, cut off from

the inner life element that is connected with the Sun, they want to

keep it in the condition of separation. And their activity produces

the result that man does not get a conscious feeling: thinking is

connected with inner fashioning, but feels instead that thinking is

only connected with the external, precisely with that which is

separated. Thus in respect of thinking they evoke a feeling that it

can only reproduce the external; that one cannot grasp the inner

formative living element with it, but can only grasp the external.

Thus they falsify our thinking.

It was in fact the karma of Western

humanity to make acquaintance with these spirits, who falsify

thinking in this manner, alter it, externalise it, who endeavour to

give it the stamp of only being of service in reproducing outer

things and not grasping the inner living element. It was apportioned

to the karma of the Oriental peoples to be preserved from this kind

of Luciferic element. Hence they retained more the consciousness that

in thinking one must seek for the inwardly forming, shaping of the

human being, for what unites him inwardly with the living

thought-world of the universe. It was allotted to the Greeks to form

the transition between the one and the other.

Since the Orientals have made little

acquaintance with that Luciferic element I have just characterised,

they have no real idea that one can also come into connection with

the living element of thinking about the external. What they get hold

of in this connection always seems made of

papier-mâché; they have little understanding of

applying thinking to outer things. Lucifer must of course cooperate

in the activity which I have just described, by which man feels the

inclination to meditate on the outer world. But then it is like the

swing of the pendulum to one side, man goes too far in this activity

— towards the external. That is the common

peculiarity of all life; it swings out sometimes to the one side,

sometimes to the other. There must be the swinging out, but one must

find the way back from the one to the other, from the Oriental to the

Occidental. The Greeks were to find the transition from Oriental to

Occidental. The Oriental would have fallen completely into rigid

abstractions — has, indeed, partly done so,

abstractions which are pleasing to many people —

if Greece had not influenced the world. If we base our judgment

simply on what we have now considered, we shall find in Greece the

tendency to make thoughts inwardly formative and alive.

Now if you examine both Greek literature

and Grecian art you will everywhere find how the Greek strove to

produce the human form from his own inner experiencing; this is so in

sculpture as well as in poetry, in fact in philosophy too. If you

acquaint yourself with the manner in which Plato still sought, not to

found an abstract philosophy, but to collect a group of men who talk

with one another and exchange their views, so that in Plato we find

no world-concept (we have only discussions) but men who converse, in

whom thought works humanly, thoughts externalise, you will find this

corroborated. Thus even in philosophy we do not have the thought

expressing itself so abstractly, but it clothes itself as it were in

the human being representing it.

When in this way one sees Socrates

converse, one cannot speak of Socrates on the one hand and of a

Socratic world-conception on the other. It is a unity, one complete

whole. One could not imagine in ancient Greece that someone

— let us say, like a modern philosopher

— came forward who had founded an abstract

philosophy, and who placed himself before people and said: this is

not the correct philosophy. That would have been impossible

— it would only be possible in the case of a

modern philosopher, (for this rests secretly in the mind of them

each). The Greek Plato, however, depicts Socrates as the embodied

world-conception, and one must imagine that the thoughts have no

desire to be expressed by Socrates merely to impart knowledge of the

world, but that they go about in the figure of Socrates and are

related to people in the same way as he is. And to pour, as it were,

this element of making thought human into the external form and

figure, constitutes the greatness in the works of Homer and

Sophocles, and in all the figures of sculpture and poetry which

Greece has created. The reason why the sculptured gods of Grecian

statuary are so human is that what I have just expressed was poured

into them. This is at the same time a proof of how humanity's

evolution in a spiritual respect strove as it were to grasp the

living element of man from the thought-element of the cosmos and then

to give it form. Hence the Grecian works of art appear to us (to

Goethe they appeared so in the most eminent sense) as something which

of its kind is hardly to be enhanced, to be brought to greater

perfection, because all that was left of the ancient revelation of

actively working and weaving thoughts had been gathered up and poured

into the form. It was like a striving to draw together into the human

form all that could be found as thoughts passing from within

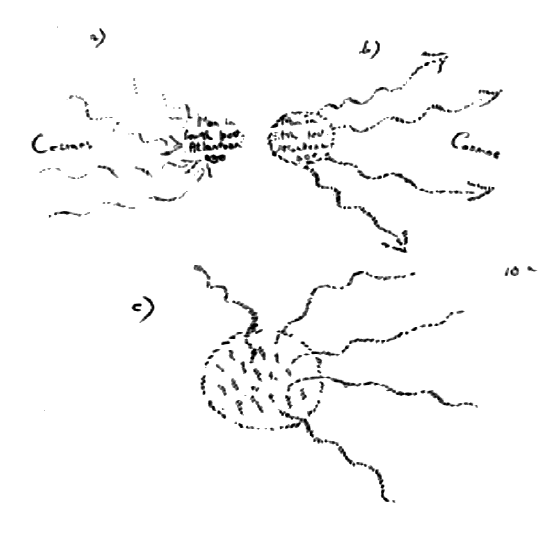

outwards, and this became in Greece philosophy, art, sculpture. (See

Diagram (a) p.8a)

A more modern age has another mission,

the present time has an entirely different task. We now have the task

of giving back to the universe that which there is in man. (Diagram

(b)). The whole pre-Grecian evolution led to man's taking from the

universe all that he could discover of the living element of the

human form in order to epitomise it. That is the unending greatness

of Greek art — that the whole preceding world is

actually epitomised and given form in it. Now we have the task

reversed — the human being, who has been

immeasurably deepened through the Mystery of Golgotha, who has been

inwardly seized in his cosmic significance, is now to be given back

again to the universe.

You must, however, inscribe in your

souls that the Greeks had not, of course, the Christian view of the

Mystery of Golgotha; for them everything flowed together out of the

cosmic wisdom:

And now picture the immense, the

immeasurable advance in the evolution of humanity when the Being who

had formerly worked from the cosmos and who could only be known from

the cosmos, and whom man could express in the earthly stage in the

element of Form: — when this Being passed out of

the cosmos into the earth, became man, and lives on in human

evolution.

That which was sought out in the cosmos

in pre-Grecian times now came into the earth, and that which had been

poured out into form, was now itself in human evolution. (c)

Naturally (I have therefore indicated it with dots) it is not yet

rightly known — it is not yet rightly experienced,

but it lives in man, and men have the task of giving it back

gradually to the cosmos. We can picture this quite concretely, this

giving back to the cosmos of what we have received through Christ. We

must only not struggle against this giving back. One can really cling

closely to the wonderful words: ‘I am with you all

the days until the end of the Earth period.’

This means: what Christ has to reveal to

us is not exhausted with what stands in the Gospel. He is not among

us as one who is dead, who once upon a time permitted to be poured

into the Gospels what he wished to bring upon earth, but he is in

earthly evolution as a living Being. We can work through to him with

our souls, and he then reveals himself to us as he revealed himself

to the Evangelists. The gospel is therefore not something that was

once there and then came to an end, the gospel is a continuous

revelation. One stands as it were ever confronting the Christ, and

looking up to Him, one waits again for revelation.

Assuredly he —

whoever he may have been — who said:

‘I should still have much to write but all the

books in the world could not contain it’

— assuredly he, John, was entirely right. For if

he had written all that he could write, he would have had to write

all that would gradually in the course of human evolution result from

the Christ event. He wished to indicate: Wait! Only wait! What all

the books in the world could not contain will come to pass. We have

heard the Christ, but our descendants will also hear Him, and so we

continuously, perpetually, receive the Christ revelation. To receive

the Christ revelation means: to acquire light upon the world from

Him. And we must give back the truths to the cosmos from the centre

of our heart and soul.

Hence we may understand as living

Christ-revelation what we have received as Spiritual Science. He it

is who tells us how the earth has originated, the nature of the human

being, what conditions the earth passed through before it became

earth. All that we have as cosmology, and give back to the universe,

all this is revealed to us by Him. It is the continuous revelation of

Christ to feel such a mood as this: that one receives the cosmos from

the Christ in an inward spiritual way, drawn together as it were, and

as one has received it to relate it to the world with understanding,

so that one no longer looks up to the moon and stares at it as a

great skittles-ball with which mechanical forces have moved skittles

in the cosmos and which from these irregularities has acquired

wrinkles, and so on — but recognises what the moon

indicates, how it is connected with the Christ-nature and the

Jahve-nature. It is a continuous revelation of the Christ to allot

again to the outer world what we have received from Him. It is at

first a process of knowledge. It begins with an intellectual process,

later it will be other processes. Processes of inner feeling will

result which arise from ourselves and pour themselves into the

cosmos, such processes as these will arise.

But you gather something else from what

I have just explained. When you observe this motion- (Diagram (a)

p.10a) where one has gathered up out of the cosmos, as it were, the

component parts of the human being, which have in the Greek

world-concepts, in Greek art, then flowed together to the whole human

being, then you will understand: In Greece the evolution of humanity

strove towards the plastic form, sculptured-form, and what they have

reached in such form, we cannot as a matter of fact succeed in

copying. If we imitate it nothing true or genuine results. That is

therefore a certain apex in human evolution. One can in fact say this

stream of humanity strives in Greece in sculpture towards a

concentration of the entire human evolution preceding

Greece.

When, on the contrary, one takes what

has to happen here (b) it is what could be called a distribution of

the component parts of man into the cosmos. You can follow this in

its details. We assign our physical body to Saturn, the etheric body

to the Sun, the astral body to the Moon, our Ego-organisation to the

Earth. We really distribute man into the universe, and it can be said

that the whole construction of Spiritual Science is based upon a

distribution, a bringing again into movement, of what is concentrated

in the human being. The fundamental key of this new world-conception

(diagram (b)) is a musical one; of the old world (a) is a plastic

one. The fundamental key of the new age is truly musical, the world

will become more and more musical. And to know how man is rightly

placed in the direction towards which human evolution is striving,

means to know that we must strive towards a musical element, that we

dare not recapitulate the old plastic element, but must strive

towards a musical one.

I have frequently mentioned that on an

important site in our Building there will be set up the figure of

archetypal man, which one can also speak of as the Christ, and which

will have Lucifer on the one side and Ahriman on the other. What is

concentrated in the Christ we take out and distribute again in

Lucifer and Ahriman, in so far as it is to be distributed. What was

welded together plastically in the one figure we make musical,

inasmuch as we make it a kind of melody:

Christus-Lucifer-Ahriman.

Our Building is really formed on this

principle. Our whole Building bears the special imprint in it: to

bring plastic forms into musical movement. That is its fundamental

character. If you do not forget that, in mentioning something like

this, one is never to be arrogant, but to remain properly humble, and

if you remember that in all that concerns our work on this Building

only the first most imperfect steps have been taken, you will not

misunderstand what is meant when I speak about it. It is of course

not meant that anything at all of what floats before us as distant

ideal is also only attained in the farthest future; but a beginning

can be sought in that direction, — this one can

say. More shall not be said than, that a beginning is

desired.

But when you compare this beginning with

that which has undergone a certain completion in Greece, with the

infinite perfection of the plastic principle in, for instance, the

Greek you find polaric difference. In Greece everything strives for

form. An Acropolis figure of Athena, or in the architecture of the

Acropolis, or a Greek Temple, they stand there in order to remain

eternally rigid in this form, in order to preserve for man a picture

of what beauty in form can be.

Such a work as our Building, even when

one day it becomes more perfect, will always stand there in such a

way that one must actually say: this Building always stimulates one

to overcome it as such, in order to come out through its form into

the infinite. These columns and in particular the forms connected

with the columns, and even what is painted and moulded, is all there

in order, so to say, to break through the walls, in order to protest

against the walls standing there and in order to dissolve the forms,

dissolve them into a sort of etheric eye, so that they may lead one

out into the far spaces of the Cosmic thought-world.

One will experience this building in the

right way if one has the feeling in observing it that it dissolves,

it overcomes its own boundaries; all that forms walls really wants to

escape into cosmic distances. Then one has the right feeling. With a

Greek temple one feels as if, one would like best to be united for

ever with what is firmly enclosed by the walls and with what can only

come in through the walls. Here, with our Building, one will

particularly feel: If only these walls were not so tiresomely there

— for wherever they stand they really want to be

broken through, and lead out further into world of the cosmos. This

is indeed how this Building should be formed, according to the tasks

of our age, really out of the tasks of our age.

Since we have not only spoken for years,

my dear friends, on the subjects of Spiritual Science, but have

discussed with one another the right attitude of mind towards what is

brought to expression through Spiritual Science, it can also be

understood that when something in the world is criticised, one does

not mean it at all as absolute depreciation, absolute blame, but that

one uses phrases of apparent condemnation in order to characterise

facts in the right connection.

When, therefore, one reproaches a

world-historical personality, this does not imply that one would like

to declare at the same time one's desire — at

least in the criticism of this person — to be an

executioner who cuts off his head — figuratively

spoken — by expressing a judgment. This is the

case with modern critics, but not with someone imbued with the

attitude of mind of Spiritual Science. Please also take what I have

now to say in the sense indicated through these words.

An incision had at some time to be made

in mankind's evolution; it had at some time to be said: This is now

the end of all that has been handed down from old times to the

present: something new must being (diagram Page 109 (a)). This

incision was not made all at once, it was in fact made in various

stages, but it meets us in history quite clearly. Take, for instance,

such an historical personality as the Roman Emperor Augustus, whose

rule in Rome coincided with the birth of the current which we trace

from the Mystery of Golgotha. It is very difficult today to make

people fully clear wherein lay the quite essentially new element

which entered Western evolution through the Emperor Augustus, as

compared with what had already existed in Western civilisation till

then, under the influence of the Roman Republic. One must in fact

make use of concepts to which people are little accustomed today, if

one wishes to analyse something of this sort. When one reads history

books presenting the time of the Roman Republic as far as the Empire,

one has the feeling that the historians wrote as if they imagined

that the Roman Consuls and Roman Tribunes acted more or less in the

manner of a President of a modern republic. Not much difference

prevails whether Niebuhr or Mommsen speaks of the Roman Republic or

of a modern republic, because nowadays people see everything through

the spectacles of what they see directly in their own environment.

People cannot imagine that what a man in earlier times felt and

thought, felt too as regards public life, was something essentially

different from what the present-day man feels. It was however

radically different, and one does not really understand the age of

the Roman Republic if one does not furnish oneself with a certain

idea which was active in the conception of the old republican Roman,

and which he took over into the age which is called the Roman

Empire.

The ancient kings, from Romulus to

Tarquinius Superbus [pronounced,

su-PERB-us – e.Ed], were to the ancient Romans actual beings, who

were intimately connected with the divine, with the divinely

spiritual world rulership. And the ancient Roman of the time of the

kings could not grasp the significance of his kings otherwise than by

thinking: In all that takes place there is something of the nature of

what happened in the time ofNuma

Pompilius, who visited the

nymphEgeria in order to know how he should act. From the gods,

or from spirit-land one received the inspirations for what had to be

done upon earth. That was a living consciousness. The kings were the

bridges between what happened on earth and what the gods out of the

spiritual world wished to come about.

Thus a feeling extended over public life

which was derived from the old world conception —

namely, that what a man does in the world is connected with what

forms him from the cosmos, so that currents continually stream in

from the cosmos. Nor was this idea confined to the government of

mankind. Think of Plato: he did not chisel things out in his soul as

ideas, but received them as outflow of the divine being. So too in

ancient Rome they did not say to themselves: One man rules other men,

but they said: The gods rule men, and he who in human form is

governing, is only the vessel into which the impulses of the gods

flow. This feeling lasted into the time of the Roman Republic when it

was related to the Consular office. The Consular dignity in ancient

times was not that genuine so-called bourgeois-element, as it were,

which a state- government increasingly feels itself to be today, but

the Romans really had the thought, the feeling, the living

experience: Only he can be Consul whose senses are still open to

receive what the gods wish to let flow into human

evolution.

As the Republic went on and great

discrepancies and quarrels arose, it was less and less possible to

hold such sentiments, and this finally led to the end of the Roman

Republic. The matter stood somewhat thus: People thought to

themselves: if the Republic is said to have a significance in the

world, the Consuls must be divinely inspired men, they must bring

down what comes from the gods. But if one looks at the later Consuls

of the Republic one can say to oneself: The gentlemen are no longer

the proper instruments for the gods. And with this is linked the fact

that it was no longer possible to have such a vital feeling for the

significance of the Republic. The development of such a feeling lay

of course behind men's ordinary consciousness. It lay very deep in

the subconscious, and was only present in the consciousness of the

so-called initiates. The initiates were fully cognisant of these

things. Whoever therefore in the later Roman Republic was no ordinary

materialistically thinking average citizen said to himself: 'Oh, this

Consul, he doesn't please me — he's certainly not

a divine instrument!' The initiate would never have admitted that, he

would have said: He is, nevertheless, a divine instrument

— Only ... with advancing evolution

this divine inspiration could enter mankind less and less. Human

evolution took on such a form that the divine could enter less and

less, and so it came about that when an initiate, a real initiate

appeared who saw through all this, he would have to say to himself:

We cannot go on any further like this! We must now call upon another

divine element which is more withdrawn from man. Men had developed

outwardly, morally, etc., in such a way that one could no longer have

confidence in those who were Consuls. One could not be sure that

where the man's own development was in opposition to the divine, that

the divine still entered. Hence the decision was reached to draw

down, as it were, the instreaming of the divine into a sphere which

was more withdrawn from men. Augustus, who was an initiate to a

certain degree in these mysteries, was well aware of this. Therefore

it was his endeavour to withdraw the divine world rulership from what

men had hitherto, and to work in the direction of introducing the

principle of heredity in the appointment to the office of Consul. He

was anxious that the Consuls should no longer be chosen as they had

been up to then, but that the office should be transmitted through

the blood, so that what the Gods willed might be transmitted in this

way. The continuance of the divine element in man was pressed down to

a stage lying beneath the threshold of consciousness because men had

reached a stage where they were no longer willing to accept the

divine. You only arrive at a real understanding of this

extraordinarily remarkable figure of Augustus, if you assume that he

was fully conscious of these things, and that out of full

consciousness, under the influence of the Athenian initiates in

particular who came to him, he did all the things that are recorded

of him. His limitation only lay in the fact that he could reach no

understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha, that he only saw how human

beings come down into matter, but could not conceive how the divine

element should take anchor in the material of the blood. He had no

understanding of the fact that something entirely new had now arisen

in the Mystery of Golgotha. He was in a high sense an initiate of the

old Mysteries, but he had no understanding for what was then emerging

in the human race as a new element.

The point is, however, that what

Augustus had accomplished was an impossibility. The divine cannot

anchor in the pure material of the blood in earthly evolution, unless

this earthly evolution is to fall into the Luciferic. Men would never

be able to evolve if they could only do so as the blood willed, that

is, developing from generation to generation what was already there

before. However, something infinitely significant is connected with

the accomplishment of this fact. You must remember that in early

times when the ancient Mysteries were in force people possessed in

the Mysteries a constant and powerfully active spiritual element,

although that cannot be significant to us in the same way today. They

knew, nevertheless, of the spiritual worlds; they came quite

substantially into the human mind. And on the other hand people

ceased in the time of Augustus to know anything of the spiritual

element of the world; they no longer knew of it in consequence of

man's necessary evolution. The Augustus-initiation actually consisted

in his knowledge that men would become less and less fitted to take

in the Spiritual element in the old way. There is an immense tragedy

in what was taking place round the figure of Augustus. The ancient

Mysteries were still in existence at that time, but the feeling

continually arose: Something is not right in these ancient Mysteries.

What was received from them was of immeasurable significance, a

sublime spiritual knowledge. But it was also felt that something of

immeasurable significance was approaching; the Mystery of Golgotha,

which cannot be grasped with the old Mystery knowledge, with which

the old Mystery knowledge was not in keeping. What could, however, be

known to men through the Mystery of Golgotha itself was still very

little. As a matter of fact even with our spiritual science we are

today only at the beginning of understanding what has flowed into

humanity with the Mystery of Golgotha. Thus there was something like

a breaking away from the old elements, and we can understand that

more and more there were men who said: We can do nothing with what

comes to us from the Mystery of Golgotha. These were men who stood at

a certain spiritual eminence in the old sense, the sense of the

pre-Christian, the pre-Golgotha time.

Such men said to themselves: Yes, we

have been told of one, Christus, who has spread certain teachings.

They did not yet feel the deeper nature of these teachings, but what

they heard of them seemed to be like warmed-up ancient wisdom. It was

told them that some person had been condemned, had died on the cross,

had taught this and that. This generally seemed to them false and

deceptive, whereas the ancient wisdom which was handed down to them

seemed enormously grand and splendid. Out of this atmosphere we can

understand Julian the Apostate, whose entire mood can be understood

in this way. More and more, individuals came forward who said: That

which is given by the old wisdom, the way it explains the cosmos,

cannot be united with that which blossoms, as if from a new centre,

through the Mystery of Golgotha. — One of the

individuals who felt this way was the sixth century Byzantine emperor

Justinian (who lived from 527–565

[According to the Encyclopaedia

Britannica, Justinian lived from 482–565, and

ruled from 527–565.]), whose actions are to be understood from exactly

this viewpoint. One must understand that he felt, through the whole

manner in which he grew into his time, that something new was in the

world ... at the same time there came into this new world that which

was handed down from the old time. We will consider just three of

these things which were thus handed down.

For a long time (five or six centuries)

Rome had been ruled by emperors: The rank of consul, however, had

existed for only a short time, and, like a shadow of the old times,

these consuls were elected. If one looked at this election of consuls

with the eyes of Justinian, one saw something which no longer made

any sense, which had true meaning in the time of the Roman Republic,

but was now without meaning: therefore he abolished the rank of

consul. That was the first thing.

The second was that the Athenian-Greek

schools were still in existence; in these was taught the old

mystery-wisdom, which contained a much greater store of wisdom than

that which was then being received under the influence of the Mystery

of Golgotha. But this old mystery-wisdom contained nothing about the

Mystery of Golgotha. For that reason Justinian closed the old Greek

Philosophers' Schools.

Origenes, the Church Teacher, was well

versed in what was connected with the Mystery of Golgotha, even

though he still stood in the old wisdom, although not as strict

initiate, yet as one having knowledge to a high degree. In his

world-concept he had amalgamated the Christ-Event with the

World-conception of the ancient, wisdom, he sought through this. to

understand the Christ Event. That is just the interesting thing in

the world concept of Origenes, that he was one of those who

especially sought to grasp the Mystery of Golgotha in the sense of

the old mystery wisdom. And the tragedy is that Origenes was

condemned by the Catholic Church.

Augustus was the first stage. (see the

lined diagram p.10a) Justinian in this sense was the second stage.

Thus the earlier age is divided from the newer age, which- as regards

the West — had no longer understanding for the

Mystery wisdom. This wisdom had still lived on in the Grecian schools

of philosophy, and had gradually to work towards the growth and

prosperity of that current in mankind which proceeded from the

Mystery of Golgotha. So it came about that the newer humanity, with

the condemning of Origenes, with the closing of the Greek schools of

philosophy, lost an infinite amount of the old spiritual treasure of

wisdom. The later centuries of the Middle Ages worked for the most

part with Aristotle, who sought to encompass the ancient wisdom

through human intellect. Plato still received it from the ancient

mysteries, Aristotle — he is, to be sure,

infinitely deeper than modern philosophers — did

not regard wisdom as a treasure of the Mysteries; he wished to grasp

it with the human understanding. Thus what prevailed at that time in

a noted degree was a thrusting back of the old Mystery

Wisdom.

All this is connected with the

perfecting in the new age of the condition which I described at the

beginning of today's lecture. Had not the Grecian schools of

philosophy been closed we should have possessed the living Plato, not

that dead Plato whom the Renaissance produced, not the Platonism of

modern times, which is a ghastly misconception of

[missing text]