Knowledge as a Source of Healing

Lecture II

Dornach, 21st March 1920

It behoves me today to

link certain aspects of the knowledge gained from earlier studies —

with which most of our friends are already acquainted — to what I

said yesterday. But once again I want to draw your attention to the

essential content of what was then said, namely, that the knowledge,

the passive kind of knowledge cultivated todays is in reality a

comparatively recent production. This indifferent knowledge, shown for

instance when medicine is set down as just one science among many, has

been developed only in course of the last three or four centuries;

whereas in olden times the aim of all knowledge was to heal. Knowledge

and the firding of means to heal mankind were, in the sense intended

yesterday, one and the same.

Now from various

indications in my lectures you mill know that in the last third of the

nineteenth century an event of spiritual importance took place; that

during the seventies of that century, behind the scenes of

world-history, of outer, physical world-history, something of great

significance happened. We have some name for it but another name might

do just as well — we have called it the victory of the

archangelic Being, Michael, over opposing spiritual forces. We will

look upon this as an event taking place in the spiritual World and

connected with mankind's history. It is in the spiritual world that

such events are prepared. This particular one could be said to be in

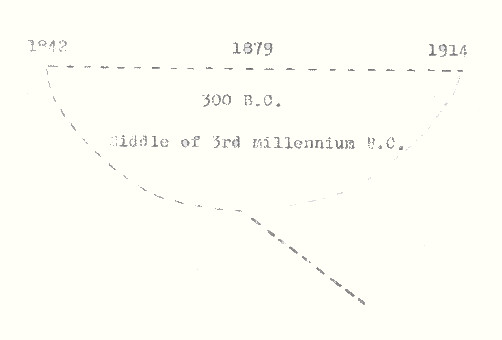

preparation already it 1842. It reached a certain climax in the

spiritual world about 1879, and from 1914 on the necessity arose for

men on earth to establish a harmonious relation with this spiritual

event. What has been happening since 1914 is essentially a struggle on

the part of narrow-minded humanity against what, in the opinion of the

spiritual powers concerned with the guidance of mankind, should come

about. Thus we may say: In the second half of the nineteenth century

and first half of the twentieth, behind the scenes of human evolution,

there was taking place something significant — a challenge to men

to submit themselves to the will of those spiritual beings. This would

entail a change of direction and the bringing about of a new kind of

civilisation, a new conception of social life, of the life of art and

all spiritual life on earth. In the course of human evolution there

have repeatedly been such events, of which external history takes

little account. For external history is indeed a fabrication. Things of

this kind have nevertheless definitely happened — one of them taking

place 300 years, another in the middle of the third millennium, before

the birth of Christ.

1842───────────────1879───────────────1914

300 B.C.

Middle of the 3rd Millennium

Regarding mankind,

however, there was a great difference between the experiencing of these

two events and that of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Most of

you have at least partly experienced the events of the second half of

the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth, and will know

that small notice was taken of how a change should actually come about

in the spiritual life.

Hardship will compel

mankind to realise the neceesity for this. There will be no end to

hardship until a sufficient number of human beings have realised this

necessity — even in the organising of public affairs. We may

indeed ask why no notice has been taken, and whether it was the same in

the case of those other experiences, the third millennium and the third

century. — But no, it was quite different then. Cculd people only

interpret to history of the Greek soul rightly, even that of the more

coarse-grained Romans, they would understand that actually both Greeks

and Romans were fully aware that something calling for notice was

taking place in the spiritual world. Indeed precisely in the case of

the event 300 years before Christ's birth, we can quite well see its

gradual preparation, how it then reached a climax and lived itself out.

The men of the third, fourth century before Christ's birth were clearly

conscious: In the world of spirit something is happening that has an

echo in the world of men. — What they thus perceived can today be

called the birth of human phantasy — man's faculty or

imagination.

You see, human beings, as

they are constituted today, consider the way they think: and the way

they feel to be the same as thinking and feeling have always been. But

that is not so. Indeed in the course of time our sense-perceptions have

changed — as I showed yesterday. Naturally, three or four

centuries before the birth of Christ creative art was already in

existence; it did not arise, however, out of what today is called

imagination but out of imagination that was clairvoyant. There who were

artists could perceive how the spiritual revealed itself, and they

simply copied what was thus revealed. The old atavistic clairvoyance,

the old imagination, was inherent in the artist. The phantasy which

then arose and was developed till, having come to the climax in the

works of Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, it started to degenerate

— this phantasy did not create as if the spiritual appeared in

imaginations, but as if something were ordered from within a man,

formed from within him. The gift of this phantasy was ascribed by

people at that time to strife among the divine beings ruling over them,

at whose orders they carried out their earthly deeds.

In the middle of that

third millennium, about 2,500 years before Christ's birth, people

perceived as something of still greater significance how their whole

being was involved in the events which, out of the spiritual world t,

made an impact on physical events. About that time, still in the third

millennium before our era, it would have been deemed very foolish to

speak of man's earthly pilgrimage without referring to the spiritual

beings around him. This would have seemed noneenee to everyone, for

then the earth was thought to be peopled by beings both physical and

spiritual.

The life of soul that

became habitual in the course of the nineteenth century is certainly

different from the of those olden days. Men perceived the ordinary

secular events on earth but not the underlying, significantv spiritual

strife. How came it that this was not perceived? — It was the

result of the special character of our present age, the age which began

it the middle of the fifteenth century and is called by us the fifth

post-Atlantean epoch. In our present epoch the most outstanding,

significant force of which a man can avail himself is intellect, and

since the fifteenth century people have attained to great heights as

intelligent beings. Today they still take pride in this. It should not

be thought, however, that in earlier times there was no kind of

intelligence — it was a different kind, it is true, but it arose

at the same time as a certain perception. This intelligence was

endowed, too, with a spiritual content. We, on the other hand, have an

intelligence devoid of spiritual content, a formal intelligence; for in

themselves our concepts and ideas are empty — they merely reflect

something. Our whole understanding is just a mass of reflected images.

It is indeed in the nature of this intelligence, which has been

particularly developed since the middle of the fifteenth century, to be

simply a reflecting apparatus. What is thus merely reflected does not

act within man as a force; it is simply passive. And it is

characteristic of this intellect — of which we are so proud

— to be passive; we just let it work upon us, give ourselves up

to it. Very little force of will is developed in it thus. The most

outstanding trait in men now is their hatred of intellect that is

active. In face of a situation where thinking is required of them

— well, they find that very boring. Whel it is a question of real

thinking there is a general dropping off to sleep — at any rate

for the soul. On the other hand, with a film, a cinematograph, when

there is ne need to think and it is thiaking that can go to sleep, when

all one has to do is to gaze and passively to give oneself up to what

is reeled off, so that thoughts run on of themselves, then there is

general satisfaction. It is a passive understanding to which men have

grown accustomed, an understanding devoid of force. And what in fact is

that? We realise its nature when looking back at the distinction made

in human knowledge in the old Mystery schools. There were three

categories: first, the knowledge that came from men's physical life,

arising out of their common physical experience of the world. Perhaps

we could say: First, physical knowledge; secondly, intellectual

knowledge, developed by man himself, chiefly in mathematics, knowledge,

in effect, in which a man immerses himself — intellectual

knowledge; and thirdly, spiritual knowledge, coming from the spiritual

and not from the physical. Today, of these three it is intellectual

knowledge which is especially cultivated and most in favour. It has

become quite an ideal to approach the spiritual life with the passive,

unconcerned attitude usually adopted towards mathematics. It is not

admitted but all the same true that our present men of learning, for

instance our university professors, on leaving the lecture-room like to

turn as soon as they can to something quite unconnected with their

particular subject. That betrays an abstract relation to knowledge

which goes extremely deep.

When I was lecturing in

Zurich a few days ago, a workman broke into the discussion. As the

Waldorf School and the timetable we have put in place of the usual

soul-destroying one had been mentioned, he said: “Your timetable

gives too long a stretch for one subject; there should be more change.

For when children have gone on with a subject from eight to nine, if

they are not to be bored there ought to be something else from nine to

ten.” Naturally I could but reply: “It is not the business

of the Waldorf School to deal with boredom but to take care that the

children's interest is kept alive — and that is the concern of

the School pedagogics and didactics.” Thus the idea is very

deeply-rooted in people that spiritual life is boring, and easily

becomes tiresome as a subject. This is entirely because our

intellectual life, consisting as it does merely of pictures, of

reflected images, can provide no substance for our spiritual life. And

a spiritual life devoid of substance is in a state of isolation —

cut off not only from the spiritual world but also from the physical.

Actually in the age we live in very little is known either of the

physical world or that of the spirit. All that a man knows about is his

own imaginings. As a result of intellectuality being just so many

reflected images, the man of the nineteenth century was debarred from

any knowledge of what was going on spiritually behind the scenes of

world-history. He had no share in the experience of that great,

momentous change which, behind external world history, came about in

the spiritual world during the second half of the nineteenth century.

It is through hiP own endeavours that he has to learn how the physical

world should follow the lead of the spiritual world. This lesson is

forced upon him, for, if not learnt, increasing hardship will prevail

and all present civilisation will go down into barbarism. To avoid this

it is necessary for people to be aware inwardly that they must

experience something in the same way that, 300 years before Christ's

birth, the birth of phantasy was experienced. In our day we have to

experience the birth of active intelligence — at that time the

active force of imagination arose. At that time it became possible to

give imaginative shape to what was created in accordance with external

form; now, people must turn to the inward, vicsorous creation of ideas,

through which everyone makes for himself a picture of his own being

— setting it before him as a goal. Human beings must acquire

self-knowledge in its widest sense, not just by brooding over what they

had for dinner, but ,a self-knowledge which sets their whole being in

action. That is the kind of self-knowledge demanded for the evolution

of those men whose present task is the bringing to birth of an active

intelligence.

Now, it will happen that

human beings in ordinary recollection, in their ordinary memory, will

discover something very peculiar. Because people today have become

rather insensitive and do not notice what is already in their souls, on

looking back over their life they still perceive only memories of their

ordinary experiences. But that is not the whole picture; actually a

certain change has taken place and more and more people are met with

who are having a new experience. When these men look back ten or twenty

years they come not only to what they have experienced, but out of

that, like an independent entity, there rises something they have not

experienced. Psycho-analysis, in its foolishness, examines what thus,

lies hidden in the soul examines it without realising the nature of our

present age. What these foolish psycho-analysts are unable to find,

spiritual science must propound, namely, that when we look back —

say from our 45th year — and watch our experiences surging past

like a stream (see diagram), within them there is not only our past

experience; it was so once and even today is all that most of our

rather thick-skinned generation perceive. But anyone sensitive to such

things will realise that in a backward survey of his life he sees not

only the ordinary events but something (red in diagram) he has not

experienced, arising from the past experiences of his soul in an almost

demoniacal way. And this will increase in intensity. If people do not

learn to observe such things they will lose the power to understand

them.

Therein lies the danger

for future evolution, and deluding oneself is of no avail for it is

indeed so. Among the experiences lived through by a man something new

will appear, only to be grasped by active intelligence. This is

extraordinarily important. Just as in the individual human being

something new arises after the change of teeth, then again at puberty,

and so on, after a certain period the same kind of metamorphosis occurs

in mankind as a whole. This present metamorphosis can be described as

follows — if we look back occasionally on our life (and this can also

be done in the backward survey over our day) we do not only remember

the most obvious experiences, but out of these surge up demonic forms.

It almost causes us to say: I have had certain experiences out of which

daydreams arise. — This will be quite normal but we have to be

alive to it. It will cell for much more inward activity on men's part

and the overcoming of that passive attitude which promotes despair in

face of the great demands of the age. That passivity must be overcome.

People's sleepiness, their inability to rouse themselves and to take

things with dignity and in earnest, is certainly terrifying. I have

already spoken here of how in our day many people cannot even be angry.

Anyone incapable of getting angry over what is bad is incapable of

enthusiasm over what is good. When, however, active intelligence takes

possession of human beings there will be a change. We may indeed say

that they are still afraid of the discovery they will then make. For

with the coming of active intelligence they will recognise their

cherished intellectuality for what it is — recognise the real nature of

these arising images. This can be understood only if we remember

something I have often mentioned here — that we can feel, we can will,

just being alive; but just being alive does not enable us to think.

That, we cannot do. We are able to think only by bearing permanently

within us the principle of death.

This great secret about

mankind lies in there being a never-ending stream, as it were, flowing

from the sense — let us take the eye as representing them (see

diagram). Through what we know as nerve, the senses carry into a man

something destructive. It is as if — by way of the nerve-fibres

— men were filled through their senses with a crumbling material.

When you see, when you hear, even when you are conscious of warmth,

there is taking place what like the crumbling of some material on its

way inward from the senses. This crumbling material has to be taken

hold of by what streams out from within a man; it must be, as it were,

burnt up. Our thinking necessitates a continual struggle against the

forces of death in us. Indeed, because he is conscious of his thinking

merely in its reflecting capacity, a man does not realise that,

strictly speaking, he is alive only in what has nothing to do with his

head, his head actually being an organ always in the throes of death.

We should be in constant danger of death were merely that to happen

which goes on in our head. This permanent dying is checked by the head

being united to the rest of the organism, upon which it draws for its

vitality. When the human being will have possessed himself of active

intelligeace as he did of active phantasy in the days of the Greeks and

Romans — whereas the imagination of the old atavistic

clairvoyance was a passive phantasy — with this active

intelligence he will be able to perceive how part of his being is

always dying. And this will be important. For just today we have to

progress to a state of consciousness enabling us to perceive this

permanent dying, so mankind in a past age, even up to the time of the

Greeks, perceived what was living in the principle of vitality, in the

will and its associated metabolism. What fights against the principle

of death, what in a man is continuously disabling that principle of

death, is living there, it might be said that in this respect the

people of old were superior to those who followed them. They perceived

the vitality with their instinctive clairvoyance, perceived the life

with which the principle of healing is connected. Indeed, we do not die

because our head has the will to die, but, owing to our head being the

organ of thinking, we permanently carry within us the germs of

sickness. Thus it is necessary for us to pay the price of our thinking

by setting counter to the head, with its tendency to disease, the

healing forces lying in the rest of our organism. Today it is still

little noticed, but forms of disease are beaming to appear — as

you know, they change — in which the constant process of death

coming from the head will be more easily noticed than many of our

present illnesses. Then it will be found that in reality the whole

healing process in human beings is to counteract the harmful effects of

our intellectual life. Whereas people of old could claim healing to be

in their science, their knowledge, in future it will have to be

admitted that what we are now making of our intellect, what is becoming

of this intellect, of which today we are so proud, should it alone be

held valid, will show us in future the gradual fall of mankind into

complete decadence. To avert this, science will have to become able to

carry within it the forces of healing. — I indicated this

yesterday from another point of view; today I do so more from the

standpoint of the way in which man is constituted. We must reeognise

that spiritual science is needed as bearer of a new healing process.

For if there be a further development of the intellect of which modern

man is so proud, intellect which lives merely in images, then by reason

of its predominance all men will become disease-ridden. Measures must

be taken to prevent such a thing. I can well imagine some people

replying: “But if we discourage this intellectual cleverness, if

we do away with intellect”, — and there are indeed those

who would like to see the intellect left undeveloped —

“then there would be no need to repair the damage it does.”

— The true progress of mankind, however, has nothing in common

with this Jesuitical principle; rather is it a question of human

evolution beinz such that the healing element developing out of man's

soul-forces can have effect on the intellect — otherwise thie

intellect will take a decadent trend and bring about the downfall of

mankind. (See diagram)

As counter-measure to

this, what arises from knowledge of spiritual science, and can

permanently hinder the forces of decline in the one-sided intellect,

must become effectual.

We come here to a point

where once again I have to draw your attention to a very special

matter. You will certainly realise that during the nineteenth century,

when all I am telling you about today — and have frequently

pointed out in the past — was taking place, intellectual

materialism was assuming great proportions. Men came to the fore

— I need only remind you of Moleschott, Vogt, Gifford —

upholding, for instance, the proposition: All thinking consists in a

metabolism going on in the brain. — They spoke of

phosphorescenceopf the brain, and said without phosphorus in the brain

there is no thinking. According to this thinking is just a byproduct of

a certain digestive process in the brain. And the men saying this

cannot be written off as being the stupid ones among their

contemporaries. We may think how we like about the theory of these

materialists but we can just as well do something else: that is,

measure their capacity by that of their contemporaries and ask: Were

such people as Moleschott and Gifford the cleverer or those who opposed

them out of old religious prejudice and without spiritual science? Was

Haeckel the cleverer or his opponents? This question may still be asked

today. And when it is not answered in accordance with personal opinion,

but with regard to spiritual capacity, naturally it cannot be said that

Haeckel's opponents were cleverer than he nor that the opponents of

Moleschott and Gifford were cleverer than they. The materialists were

very clever people, and what they said was certainly not devoid of

significance. How then did all this come about? What was behind it? We

must indeed find the answer.

Certainly quite

well-intentioned opponents of materialism arose at the time, for

example Moriz Carriere whom I have often mentioned. Now he said: If

everything man thinks and experiences is merely concocted by the brain,

what is propounded by one party is just as much a concoction as what

the opposite party says. As far as the truth is concerned there is no

difference between a statement of Moleschott or Gifford and what is

maintained by the Pope. There is no difference because in both cases

they are concoctions of the human brain. There is no way of

distinguishing the true from the false. Yet the materialists fight for

what appears to them as the truth. They are not justified in doing so

but they are astute — capable of a certain quickness of spirit. What

then is in question here? You see, these materialists have had to arise

in an age when thinking is made up merely of images, lives merely in

images. But images are not there without something to act as reflector

— which in this case is the brain. Indeed, where ordinary

thinking is concerned — the thinking that grew to such heights in

the nineteenth century — materialists have right on their side;

that is a fact. They are no longer right, however, if they want to

maintain that the thinking which transcends that of the intellect is

also nothing but images dependent on the body, for that is not so. What

transcends the intellect can be acquired only in course of a manes

evolution: only by his becoming free of what has to do with the body.

The thinking that has come to the fore in the nineteenth century must

be explained materialistically. Though composed of images it is

entirely dependent on the instrument of the brain, and the remarkable

thing is that, for the most part, in face of the life of spirit in the

nineteenth century, materialism is actually justified. That life of

spirit is bound up with the bodily and material. It is precisely this

life of spirit which must be transcended. The human being must rise

above it and learn once more to pour spiritual substance into the

images. This can be done not only by becoming clairvoyant — as I

constantly emphasise there is no necessity for everyone to be so: for

spiritual substance can be made to flow into a man's thinking when he

reflects upon what another has already investi€ated

spiritually,„ This must not be accepted blindfold; once there, it

can be judged. Commonsense will suffice for the understanding of what

has, been investigated through spiritual science. The denial of this

means that commonsense is not given its due; and anyone who denies it

is thinking: Commonsense — civilised people have been developing a

great deal of that for a long time. Indeed these civilised people are

developing a “very assured” judgment! And if this assured

judgment is refuted by the facts they take no notice, refuse to take

notice. At the suitable motrent such matters — which speak

volumes symptomatically — are forgotten.

I will give you just one

nice little example. In 1866, at the time of the Prussian victory over

Austria, it was said that this was a proof of the superiority of

Prussian schools. It gave rise to the saying:

[First said in 1866 by Oskar Peschel — a professor

at Leipzig University.]

“It was the Prussian schoolmasters who won the 1866 victory.”

This has been constantly repeated, and it would be interesting to count

the times, between 1870 and 1914, that it was said by the qualified and

unqualified — mostly the unqualified: “The Prussian victory

was won by the schoolmaster.” — I imagine that people today

will no longer be so ready to speak anywhere in such a fashion, any

more than the truth of this other assertion will be insisted upon in

the light of present events. But in this intellectual age, when people

are so clever, they are not willing to notice the contradictions to be

found in life. Facts play very little part in the intellectual life,

but they must do so if the intellect is to be permeated with fresh

spiritual content. Then, indeed, it will be manifest that a paralysing

process, a decadent process, is appearing in men, which must be

overcome by new spiritual knowledge. In the past: men must be said to

have sensed, experienced, something of a healing nature in the

knowledge surging up from the physical body. In future they will have

to learn to see in the development of intellect the cause of disease,

and to look to the spirit for healing. The source of healing must

indeed be found again in science. This necessity, however, will arise

from an opposite direction, when it can be been how external life, even

when proficient in knowledge, makes for sickness in men and must be

counteracted by the healing principle.

Matters such as these

afford us insight into the course of human evolution — in so far

as this is a reality. Today history does not give us a real picture of

human evolution but merely worthless abstractions. Man today is

deficient in a sense of reality, having indeed very little. During the

nineteenth century, people in mid-Europe became very proficient at

giving out what of a spiritual nature was already there. One of the

most arresting examples of this is the case of Herman Grimm who, as a

writer about the works of Goethe — such as Tasso or

Iphigenie ranks very high. He was, however, quite unable to

portray Goethe the man. Although he wrote a biography of him, in it

Goethe seems a mere shadow. Spiritual force was not there in the

nineteenth oentury; people were living in images.; and images have no

power to enforce the reality which is so necessary for the future. We

must understand not only what human beings create, but above all the

human being himself, and through him nature, in a more all-embracing

sense than hitherto. I believe it to be possible for such things to

work in all seriousness upon the human heart and soul. It is likely to

be some time before a sufficient number of people allow themselves to

be fired by the knowledge that, if not permeated by the spirit, mankind

will be overcome by disease. At least those should accept this

knowledge who have come nearer to an understanding of

anthroposophy.

There is one thing which

must be recognised — that many who have accepted anthroposophy

have come to our Movement out of what I might call subtle egoistic

tendencies, wishing to have something for the comfort of their souls.

They want the satisfaction of gaining certain knowledge about the

spiritual world. But that will not do. This is not a matter of basking

in the personal satisfaction of participating in the spiritual. What

people need is actively to intervene in tilt) affairs of the material

world from out the spirit — through the spirit to gain mastery,

over the material world. There will be no end to all the misery that

has come upon mankind till people understand this and, understanding,

allow it to influence their will.

One would so gladly uee

— at least among anthroposophists — this kind of insight,

this kind of will, taking effect. Certainly it may be asked: What can a

mere handful of human beings do against the blindness of the whole

world? — But that is not right. To speak in that way has

absolutely no justification. For in saying this there is no thought

that what concerns us here is first to strengthen the will-power

— then we can await what will come. Let everyone from his own

sphere in life do what lies in him; he may then await what is done by

others. But at least let him do it — do it above all so that as

many people as possible in the world may be moved by the urgent need

for spiritual renewal.

Only if we are watchful,

and take a firm stand where anthroposophy has placed us, can we

ourselves make any progress or set our will to work on what is

necessary to ensure the progress of all mankind.

|