The New Spirituality

and the Christ Expereience of the Twentieth Century

1st Lecture

Historical Symptomology, the Year 790, Alcuin, Greeks, Platonism,

Aristotelianism, East, West, Middle, Ego

Dornach,

17 October 1920

In the lectures given here during the course on

history

[1]

several things were mentioned which, particularly at the present

time, it is especially important to consider. With regard to the historical course of humanity's

development, the much-debated question mentioned to begin with was whether the outstanding and

leading individual personalities are the principal driving forces in this development or whether

the most important things are brought about by the masses. In many circles this has always been a

point of contention and the conclusions have been drawn, more from sympathy and antipathy than

from real knowledge. This is one fact which, in a certain sense, I should like to mention as

being very important.

Another fact which, from a look at history, I

should like to mention for its importance is the following. At the beginning of the nineteenth

century Wilhelm von Humboldt

[2]

appeared with a definite declaration,

stipulating that history should be treated in such a way that one would not only consider the

individual facts which can be outwardly observed in the physical world but, out of an

encompassing, synthesizing force, would see what is at work in the unfolding of history —

which can only be found by someone who knows how to get a total view of the facts in what in a

sense is a poetic way, but in fact produces a true picture. Attention was also drawn to how in

the course of the nineteenth century it was precisely the opposite historical mode of thought and

approach which was then particularly developed, and that it was not the ideas in history that

were pursued but only a sense that was developed for the external world of facts. Attention was

also drawn to the fact that, with regard to this last question, one can only come to clarity

through spiritual science, because spiritual science alone can uncover the real driving forces of

the historical evolution of humanity.

A spiritual science of this kind was not yet

accessible to Humboldt. He spoke of ideas, but ideas indeed have no driving force

[of their own].

Ideas as such are abstractions, as I mentioned here yesterday

[3]

And anyone who

might wish to find ideas as the driving forces of history would never be able to prove that ideas

really do anything because they are nothing of real substantiality, and only something of

substantiality can do something. Spiritual science points to real spiritual forces that are

behind the sensible-physical facts, and it is in real spiritual forces such as these that the

propelling forces of history lie, even though these spiritual forces will have to be expressed

for human beings through ideas.

But we come to clarity concerning these things only

when, from a spiritual-scientific standpoint, we look more deeply into the historical development

of humanity and we will do so today in such a way that, through our considerations, certain facts

come to us which, precisely for a discerning judgement of the situation of modern humanity, will

prove to be of importance.

I have often mentioned

[4]

that

spiritual science, if it looks at history, would actually have to pursue a symptomatology; a

symptomatology constituted from the fact that one is aware that behind what takes it course as

the stream of physical-sensible facts lie the driving spiritual forces. But everywhere in

historical development there are times when what has real being and essence

(das eigentlich Wesenhafte)

comes as a symptom to the surface and can be judged discerningly from the

phenomena only if one has the possibility to penetrate more deeply from one's awareness of these

phenomena into the depths of historical development.

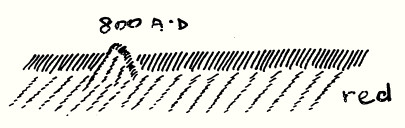

I would like to clarify this by a simple diagram.

Let us suppose that this is a flow of historical facts (see diagram). The driving forces lie, for

ordinary observation, below the flow of these facts. And if the eye of the soul observes the flow

in this way, then the real activity of the driving forces would lie beneath it (red). But there

are significant points in this flow of facts. And these significant points are distinguished by

the fact that what is otherwise hidden comes here to the surface. Thus we can say: Here, in a

particular phenomenon, which must only be properly evaluated, it was possible to become aware of

something which otherwise is at work everywhere, but which does not show itself in such a

significant manifestation.

Let us assume that this (see diagram) took place in

some year of world history, let us say around 800 AD What was significant for Europe, let us

say for Western Europe, was of course at work before this and worked on afterwards, but it did

not manifest itself in such a significant way in the time before and after as it did here. If one

points to a way of looking at history like this, a way which looks to significant moments, such a

method would be in complete accord with Goetheanism. For

Goethe

wished in general that all

perception of the world should be directed to significant points and then, from what could be

seen from such points, the remaining content of world events be recognized. Goethe says of

this

[5]

that, within the abundance of facts, the important thing is to find a

significant point from which the neighbouring areas can be viewed and from which much can be

deciphered.

So let us take this year 800 AD We can point here

to a fact in the history of Western European humanity which, from the point of view of the usual

approach to history, might seem insignificant — which one would perhaps not find worthy of

attention for what is usually called history — but which, nevertheless, for a deeper view

of humanity's development, is indeed significant. Around this year there was a kind of learned

theological argument between the man who was a sort of court philosopher of the Frankish realm,

Alcuin

[6],

and a Greek also living at that time in the kingdom of the Franks. The

Greek, who was naturally at home in the particular soul-constitution of the Greek peoples which

he had inherited, had wanted to reach a discerning judgement of the principles of Christianity

and had come to the concept of redemption. He put the question: To whom, in the redemption

through Christ Jesus, was the ransom actually paid? He, the Greek thinker, came to the solution

that the ransom had been paid to Death. Thus, in a certain sense, it was a sort of redemption

theory that this Greek developed from his thoroughly Greek mode of thinking, which was now just

becoming acquainted with Christianity. The ransom was paid to Death by the cosmic powers.

Alcuin, who stood at that time in that theological

stream which then became the determining one for the development of the Roman Catholic Church of

the West, debated in the following way about what the Greek had argued. He said: Ransom can only

be paid to a being who really exists. But death has no reality, death is only the outer limit of

reality, death itself is not real and, therefore, the ransom money could not have been paid to

Death.

Now criticism of Alcuin's way of thinking is not

what matters here. For to someone who, to a certain extent, can see through the interrelations of

the facts, the view that death is not something real resembles the view which says: Cold is not

something real, it is just a decrease in warmth, it is only a lesser warmth. Because the cold

isn't real I won't wear a winter coat in winter because I'm not going to protect myself against

something that isn't real. But we will leave that aside. We want rather to take the argument

between Alcuin and the Greek purely positively and will ask what was really happening there. For

it is indeed quite noticeable that it is not the concept of redemption itself that is discussed.

It is not discussed in such a way that in a certain sense both personalities, the Greek and the

Roman Catholic theologian, accept the same point of view, but in such a way that the Roman

Catholic theologian shifts the standpoint entirely before he takes it up at all. He does not go

on speaking in the way he had just done, but moves the whole problem into a completely different

direction. He asks: Is death something real or not? — and objects that, indeed, death is

not real.

This directs us at the outset to the fact that two

views are clashing here which arise out of completely different constitutions of soul. And,

indeed, this is the case. The Greek continued, as it were, the direction which, in the Greek

culture, had basically faded away between

Plato

and

Aristotle.

In Plato there was still something

alive of the ancient wisdom of humanity; that wisdom which takes us across to the ancient Orient

where, indeed, in ancient times a primal wisdom had lived but which had then fallen more and more

into decadence. In Plato, if we are able to understand him properly, we find the last offshoots,

if I can so call them, of this primal oriental wisdom. And then, like a rapidly developing

metamorphosis, Aristotelianism sets in which, fundamentally, presents a completely different

constitution of soul from the Platonic one. Aristotelianism represents a completely different

element in the development of humanity from Platonism. And, if we follow Aristotelianism further,

it, too, takes on different forms, different metamorphoses, but all of which have a recognizable

similarity. Thus we see how Platonism lives on like an ancient heritage in this Greek who has to

contend against Alcuin, and how in Alcuin, on the other hand, Aristotelianism is already present.

And we are directed, by looking at these two individuals, to that fluctuation which took place on

European soil between two — one cannot really say world-views — but two human

constitutions of soul, one of which has its origin in ancient times in the Orient, and another,

which we do not find in the Orient but which, entering in later, arose in the central regions of

civilization and was first grasped by Aristotle. In Aristotle, however, this only sounds a first

quiet note, for much of Greek culture was still alive in him. It develops then with particular

vehemence in the Roman culture within which it had been prepared long before Aristotle, and,

indeed, before Plato. So that we see how, since the eighth century BC on the Italian peninsula

a particular culture, or the first hints of it, was being prepared alongside that which lived on

the Greek peninsula as a sort of last offshoot of the oriental constitution of soul. And when we

go into the differences between these two modes of human thought we find important historical

impulses. For what is expressed in these ways of thinking went over later into the feeling life

of human beings; into the configuration of human actions and so on.

Now we can ask ourselves: So what was living in

that which developed in ancient times as a world-view in the Orient, and which then, like a

latecomer, found its

[last]

offshoots in Platonism — and, indeed, still in Neoplatonism? It

was a highly spiritual culture which arose from an inner perception living pre-eminently in

pictures, in imaginations; but pictures not permeated by full consciousness, not yet permeated by

the full I-consciousness of human beings. In the spiritual life of the ancient Orient, of which

the Veda and Vedanta are the last echoes, stupendous pictures opened up of what lives in the

human being as the spiritual. But it existed in a — I beg you not to misunderstand the word

and not to confuse it with usual dreaming — it existed in a dreamlike, dim way, so that

this soul-life was not permeated

(durchwellt)

and irradiated

(durchstrahlt)

by what lives in the human being when he becomes clearly conscious of his 'I' and his own being. The

oriental was well aware that his being existed before birth, that it returns through death to the

spiritual world in which it existed before birth or conception. The oriental gazed on that which

passed through births and deaths. But he did not see as such that inner feeling which lives in

the `I am'. It was as if it were dull and hazy, as though poured out in a broad perception of the

soul

(Gesamtseelenanschauung)

which did not concentrate to such a point as that of the I-experience. Into what, then, did the

oriental actually gaze when he possessed his instinctive perception?

One can still feel how this oriental

soul-constitution was completely different from that of later humanity when, for an understanding

of this and perhaps prepared through spiritual science, one sinks meditatively into those

remarkable writings which are ascribed to

Dionysius the Areopagite.

[7]

I will not go into the question of the authorship now, I have already spoken about it on a number

of occasions. 'Nothingness'

(das Nichts)

is still spoken of there as a reality, and the existence of the external world, in the way one

views it in ordinary consciousness, is simply contrasted against this

[nothingness]

as a different reality. This talk of nothingness then

continues. In Scotus Erigena,

[8]

who lived at the court of Charles the Bald, one

still finds echoes of it, and we find the last echo then in the fifteenth century in Nicolas of

Cusa

[9]

But what was meant by the nothingness one finds in Dionysius the

Areopagite and of that which the oriental spoke of as something self-evident to him? This fades

then completely. What was this nothingness for the oriental? It was something real for him. He

turned his gaze to the world of the senses around him, and said: This sense-world is spread out

in space, flows in time, and in ordinary life world, is spread out in space, one says that what

is extended in space and flows in time is

something.

But what the oriental saw — that which was a

reality for him, which passes through births and deaths — was not contained in the space in

which the minerals are to be found, in which the plants unfold, the animals move and the human

being as a physical being moves and acts. And it was also not contained in that time in which our

thoughts, feelings and will-impulses occur. The oriental was fully aware that one must go beyond

this space in which physical things are extended and move, and beyond this time in which our

soul-forces of ordinary life are active. One must enter a completely different world; that world

which, for the external existence of time and space, is a nothing but which, nevertheless, is

something real. The oriental sensed something in contrast to the phenomena of the world which the

European still senses at most in the realm of real numbers.

When a European has fifty francs he has something.

If he spends twenty-five francs of this he still has twenty-five francs; if he then spends

fifteen francs he still has ten; if he spends this he has nothing. If now he continues to spend

he has five, ten, fifteen, twenty-five francs in debts. He still has nothing; but, indeed, he has

something very real when, instead of simply an empty wallet, he has twenty-five or fifty francs

in debts. In the real world it also signifies something very real if one has debts. There is a

great difference in one's whole situation in life between having nothing and having fifty francs'

worth of debts. These debts of fifty francs are forces just as influential on one's situation in

life as, on the other side and in an opposite sense, are fifty francs of credit. In this area the

European will probably admit to the reality of debts for, in the real world, there always has to

be something there when one has debts. The debts that one has oneself may still seem a very

negative amount, but for the person to whom they are owed they are a very positive amount!

So, when it is not just a matter of the individual

but of the world, the opposite side of zero from the credit side is truly something very real.

The oriental felt — not because he somehow speculated about it but because his perception

necessitated it he felt: Here, on the one side, I experience that which cannot be observed in

space or in time; something which, for the things and events of space and time, is nothing but

which, nevertheless, is a reality — but a different reality.

It was only through misunderstanding that there

then arose what occidental civilization gave itself up to under the leadership of Rome —

the creation of the world out of nothing with `nothing' seen as absolute `zero'. In the Orient,

where these things were originally conceived, the world does not arise out of nothing but out of

the reality I have just indicated. And an echo of what vibrates through all the oriental way of

thinking right down to Plato — the impulse of eternity of an ancient world-view —

lived in the Greek who, at the court of Charlemagne, had to debate with Alcuin. And in this

theologian Alcuin there lived a rejection of the spiritual life for which, in the Orient, this

`nothing' was the outer form. And thus, when the Greek spoke of death, whose causes lie in the

spiritual world, as something real, Alcuin could only answer: But death is nothing and therefore

cannot receive ransom.

You see, the whole polarity between the ancient

oriental way of thinking, reaching to Plato, and what followed later is expressed in this

[one]

significant moment when Alcuin debated at the court of Charlemagne with the Greek. For, what was

it that had meanwhile entered in to European civilization since Plato, particularly through the

spread of Romanism? There had entered that way of thinking which one has to comprehend through

the fact that it is directed primarily to what the human being experiences between birth and

death. And the constitution of soul which occupies itself primarily with the human being's

experiences between birth and death is the logical, legal one — the

logical-dialectical-legal one. The Orient had nothing of a logical, dialectical nature and, least

of all, a legal one. The Occident brought logical, legal thinking so strongly into the oriental

way of thinking that we ourselves find religious feeling permeated with a legalistic element. In

the Sistine Chapel in Rome, painted by the master-hand of

Michelangelo,

we see looming towards us, Christ as judge giving judgment on the good and the evil.

A legal, dialectical element has entered into the

thoughts concerning the course of the world. This was completely alien to the oriental way of

thinking. There was nothing there like guilt and atonement or redemptinn. For

[in this oriental way of thinking]

was precisely that view of the metamorphosis through which the eternal element

[in the human being]

transforms itself through births and deaths. There was that which lives in

the concept of karma. Later, however, everything was fixed into a way of looking at things which

is actually only valid for, and can only encompass, life between birth and death. But this life

between birth and death was just what had evaded the oriental. He looked far more to the core of

man's being. He had little understanding for what took place between birth and death. And now,

within this occidental culture, the way of thinking which comprehends primarily what takes place

within the span between birth and death increased

[and did so]

through those forces possessed by

the human being by virtue of having clothed his soul-and-spirit nature with a physical and

etheric body. In this constitution, in the inner experience of the soul-and-spirit element and in

the nature of this experience, which arises through the fact that one is submerged with one's

soul-and-spirit nature in a physical body, comes the inner comprehension of the 'I'. This is why

it happens in the Occident that the human being feels an inner urge to lay hold of his 'I' as

something divine. We see this urge, to comprehend the 'I' as something divine, arise in the

medieval mystics; in

Eckhart,

in

Tauler

and in others. The comprehension of the 'I' crystallizes

out with full force in the Middle (or Central) culture. Thus we can distinguish between the

Eastern culture — the time in which the 'I' is first experienced, but dimly — and the

Middle (or Central) culture — primarily that in which the 'I' is experienced. And we see

how this 'I' is experienced in the most manifold metamorphoses. First of all in that dim, dawning

way in which it arises in Eckhart, Tauler and other mystics, and then more and more distinctly

during the development of all that can originate out of this I-culture.

We then see how, within the I-culture of the

Centre, another aspect arises. At the end of the eighteenth century something comes to the fore

in Kant

[10]

which, fundamentally, cannot be explained out of the onward flow of

this I-culture. For what is it that arises through Kant? Kant looks at our perception, our

apprehension

(Erkennen),

of nature and cannot come to terms with it. Knowledge of

nature, for him, breaks down into subjective views

( Subjektivitäten);

he does not

penetrate as far as the 'I' despite the fact that he continually speaks of it and even, in some

categories, in his perceptions of time and space, would like to encompass all nature through the

'I'. Yet he does not push through to a true experience of the 'I'. He also constructs a practical

philosophy with the categorical imperative which is supposed to manifest itself out of

unfathomable regions of the human soul. Here again the 'I' does not appear.

In Kant's philosophy it is strange. The full weight

of dialectics, of logical-dialectical-legal thinking is there, in which everything is tending

towards the 'I', but he cannot reach the point of really understanding the 'I' philosophically.

There must be something preventing him here. Then comes Fichte, a pupil of Kant's, who with full

force wishes his whole philosophy to well up out of the 'I' and who, through its simplicity,

presents as the highest tenet of his philosophy the sentence: `I am'. And everything that is

truly scientific must follow from this `I am'. One should be able, as it were, to deduce, to read

from this 'I am' an entire picture of the world. Kant cannot reach the 'I am'. Fichte immediately

afterwards, while still a pupil of Kant's, hurls the `I am' at him. And everyone is amazed

— this is a pupil of Kant's speaking like this! And Fichte says:

[11]

As

far as he can understand it, Kant, if he could really think to the end, would have to think the

same as me. It is so inexplicable to Fichte that Kant thinks differently from him, that he says:

If Kant would only take things to their full conclusion, he would have to think

[as I do];

he

too, would have to come to the 'I am'. And Fichte expresses this even more clearly by saying: I

would rather take the whole of Kant's critique for a random game of ideas haphazardly thrown

together than to consider it the work of a human mind, if my philosophy did not logically follow

from Kant's. Kant, of course, rejects this. He wants nothing to do with the conclusions drawn by

Fichte.

We now see how there follows on from Fichte what

then flowered as German idealistic philosophy in

Schelling

and

Hegel,

and which provoked all the

battles of which I spoke, in part, in my lectures on the limits to a knowledge of

nature.

[12]

But we find something curious. We see how Hegel lives in a

crystal-clear

[mental]

framework of the logical-dialectical-legal element and draws from it a

world-view — but a world-view that is interested only in what occurs between birth and

death. You can go through the whole of Hegel's philosophy and you will find nothing that goes

beyond birth and death. It confines everything in world history, religion, art and science solely

to experiences occurring between birth and death.

What then is the strange thing that happened here?

Now, what came out in Fichte, Schelling and Hegel — this strongest development of the

Central culture in which the 'I' came to full consciousness, to an inner experience — was

still only a reaction, a last reaction to something else. For one can understand Kant only when

one bears the following properly in mind. (I am coming now to yet another significant point to

which a great deal can be traced). You see, Kant was still — this is clearly evident from

his earlier writings — a pupil of the rationalism of the eighteenth century, which lived

with genius in Leibnitz and pedantically in Wolff. One can see that for this rationalism the

important thing was not to come truly to a spiritual reality. Kant therefore rejected it —

this `thing in itself' as he called it — but the important thing for him was to prove. Sure

proof! Kant's writings are remarkable also in this respect. He wrote his

Critique of Pure Reason

in which he is actually asking: `How must the world be so that things can be proved

in it?' Not 'What are the realities in it?' But he actually asks: 'How must I imagine the world

so that logically, dialectically, I can give proofs in it?' This is the only point he is

concerned with and thus he tries in his

Prologomena

to give every future metaphysics

which has a claim to being truly scientific, a metaphysics for what in his way of thinking can be

proven: `Away with everything else! The devil take the reality of the world — just let me

have the art of proving! What's it to me what reality is; if I can't prove it I shan't trouble

myself over it!'

Those individuals did not, of course, think in this

way who wrote books like, for example, Christian Wolff's

[13]

Vernünftige Gedanken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen

überhaupt (Reasoned Thoughts an God, the World, and the Soul of Man, and All Things

Generally).

What mattered for them was to have a clean, self-contained system of proof, in

the way that they see proof. Kant lived in this sphere, but there was still something there

which, although an excrescence squeezed out of the world-view of the Centre, nevertheless fitted

into it. But Kant had something else which makes it inexplicable how he could become Fichte's

teacher. And yet he gives Fichte a stimulus, and Fichte comes back at him with the strong

emphasis of the 'I am'; comes back, indeed, not with proofs — one would not look for these

in Fichte — but with a fully developed inner life of soul. In Fichte there emerges, with

all the force of the inner life of soul, that which, in the Wolffians and Leibnitzites, can seem

insipid. Fichte constructs his philosophy, in a wealth of pure concepts, out of the 'I am'; but

in him they are filled with life. So, too, are they in Schelling and in Hegel. So what then had

happened with Kant who was the bridge? Now, one comes to the significant point when one traces

how Kant developed. Something else became of this pupil of Wolff by virtue of the fact that the

English philosopher, David Hume,

[14]

awoke him, as Kant himself says, out of

his dull dogmatic slumber. What is it that entered Kant here, which Fichte could no longer

understand? There entered into Kant here — it fitted badly in his case because he was too

involved with the culture of Central Europe — that which is now the culture of the West.

This came to meet him in the person of David Hume and it was here that the culture of the West

entered Kant. And in what does the peculiarity

[of this culture]

lie? In the oriental culture we

find that the 'I' still lives below, dimly, in a dream-like state in the soul-experiences which

express themselves, spread out, in imaginative pictures. In the Western culture we find that, in

a certain sense, the 'I' is smothered

(erdrückt)

by the purely external phenomena

(Tatsachen).

The 'I' is indeed present, and is present not dimly, but bores itself into

the phenomena. And here, for example, people develop a strange psychology. They do not talk here

about the soul-life in the way Fichte did, who wanted to work out everything from the one point

of the 'I', but they talk about thoughts which come together by association. People talk about

feelings, mental pictures and sensations, and say these associate — and also will-impulses

associate. One talks about the inner soul-life in terms of thoughts which associate.

Fichte speaks of the 'I'; this radiates out

thoughts. In the West the 'I' is completely omitted because it is absorbed — soaked up by

the thoughts and feelings which one treats as though they were independent of it, associating and

separating again. And one follows the life of the soul as though mental pictures linked up and

separated. Read Spencer,

[15]

read John Stuart Mill

[16]

read

the American philosophers. When they come to talk of psychology there is this curious view that

does not exclude the 'I' as in the Orient, because it is developed dimly there, but which makes

full demand of the 'I'; letting it, however, sink down into the thinking, feeling and willing

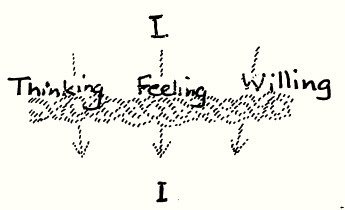

life of the soul. One could say: In the oriental the 'I' is still above thinking,

feeling and willing; it has not yet descended to the level of thinking, feeling and willing. In

the human being of the Western culture the 'I' is already below this sphere. It is below

the surface of thinking, feeling and willing so that it is no longer noticed, and thinking,

feeling and willing are then spoken of as independent forces.

This is what came to Kant in the form of the philosophy of David Hume. Then

the Central region of the earth's culture still set itself against this with all force in Fichte,

Schelling, and Hegel. After them the culture of the West overwhelms everything that is there,

with Darwinism and Spencerism.

One will only be able to come to an understanding

of what is living in humanity's development if one investigates these deeper forces. One then

finds that something developed in a natural way in the Orient which actually was purely a

spiritual life. In the Central areas something developed which was dialectical-legal, which

actually brought forth the idea of the State, because it is to this that it can be applied. It is

such thinkers as Fichte, Schelling and Hegel who, with enormous sympathy, construct a unified

image (Gebilde) of the State. But then a culture emerges in the West which proceeds from

a constitution of soul in which the 'I' is absorbed, takes its course below the level of

thinking, feeling and willing; and where, in the mental and feeling life, people speak of

associations. If only one would apply this thinking to the economic life! That is its proper

place. People went completely amiss when they started applying

[this thinking]

to something other

than the economic life. There it is great, is of genius. And had Spencer, John Stuart

Mill and David Hume applied to the institutions of the economic life what they wasted on

philosophy it would have been magnificent. If the human beings living in Central Europe had

limited to the State what is given them as their natural endowment, and if they had not, at the

same time, also wanted thereby to include the spiritual life and the economic life, something

magnificent could have come out of it. For, with what Hegel was able to think, with what Fichte

was able to think, one would have been able — had one remained within the legal-political

configuration which, in the threefold organism, we wish to separate out as the structure of the

State

[17]

— to attain something truly great. But, because there hovered

before these minds the idea that they had to create a structure for the State which included the

economic life and the spiritual life, there arose only caricatures in the place of a true form

for the State. And the spiritual life was anyway only a heritage of the ancient Orient. It was

just that people did not know that they were still living from this heritage of the ancient East.

The useful statements, for example, of Christian theology — indeed, the useful statements

still within our materialistic sciences — are either the heritage of the ancient East, or a

changeling of dialectical-legal thinking, or are already adopted, as was done by Spencer and

Mill, from the Western culture which is particularly suited for the economic life.

Thus the spiritual thinking of the ancient Orient

had been distributed over the earth, but in an instinctive way that is no longer of any use

today. Because today it is decadent, it is dialectical-political thinking which was rendered

obsolete by the world catastrophe

[World War I].

For there was no one less suited to thinking

economically than the pupils of Fichte, Schelling and Hegel. When they began to create a State

which, above all, was to become great through its economy, they had of necessity

(selbstverständlich)

to fail, for this was not what, by nature, was, endowed to

them. In accordance with the historical development of humanity, spiritual thinking, political

thinking and economic thinking were apportioned to the East, the Centre, and the West

respectively. But we have arrived at a point of humanity's development when understanding, a

common understanding, must spread equally over all humanity. How can this come about?

This can only happen out of the initiation-culture,

out of the new spiritual science, which does not develop one-sidedly, but considers everything

that appears in all areas as a three-foldness that has evolved of its own accord. This science

must really consider the threefold aspect also in social life; in this case (as a three-foldness)

encompassing the whole earth. Spiritual science, however, cannot be extended through natural

abilities; it can only be spread by people accepting those who see into these things, who can

really experience the spiritual sphere, the political sphere and the economic sphere as three

separate areas. The unity of human beings all over the earth is due to the fact that they combine

in themselves what was divided between three spheres. They themselves organize it in the social

organism in such a way that it can exist in harmony before their eyes. This, however, can only

follow from spiritual-scientific training. And we stand here at a point where we must say: In

ancient times we see individual personalities, we see them expressing in their words what was the

spirit of the time. But when we examine it closely — in the oriental culture, for example

— we find that, fundamentally, there lives instinctively in the masses a constitution of

soul which in a remarkable; quite natural way was in accord with what these individuals

spoke.

This correspondence, however, became less and less.

In our times we see the development of the opposite extreme. We see instincts arising in the

masses which are the opposite of what is beneficial for humanity. We see things arising that

absolutely call for the qualities that may arise in individuals who are able to penetrate the

depths of spiritual science. No good will come from instincts, but only from the understanding

(that Dr. Unger also spoke of here

[18])

which, as is often stressed, every

human being can bring towards the spiritual investigator if he really opens himself to healthy

human reason. Thus there will come a culture in which the single individual, with his ever-deeper

penetration into the depths of the spiritual world, will be of particular importance, and in

which die one who penetrates in this way will be valued, just as someone who works in some craft

is valued. One does not go to the tailor to have boots made or to the shoemaker to be shaved, so

why should people go to someone else for what one needs as a world-view other than to the person

who is initiated into it? And it is, indeed, just this that, particularly today and in the most

intense sense, is necessary for the good of human beings even though there is a reaction against

it, which shows how humanity still resists what is beneficial for it. This is the terrible battle

— the grave situation —in which we find ourselves.

At no other time has there been a greater need to

listen carefully to what individuals know concerning one thing or another. Nor has there been a

greater need for people with knowledge of specific subject areas to be active in social life

— not from a belief in authority but out of common sense and out of agreement based on

common sense. But, to begin with, the instincts oppose this and people believe that some sort of

good can be achieved from levelling everything. This is the serious battle in which we stand.

Sympathy and antipathy are of no help here, nor is living in slogans. Only a clear observation of

the facts can help. For today great questions are being decided — the questions as to

whether the individual or the masses have significance. In other times this was not important

because the masses and the individual were in accord with one another; individuals were, in a

certain sense, simply speaking for the masses. We are approaching more and more that time when

the individual must find completely within himself the source of what he has to find and which he

has then to put into the social life; and

[what we are now seeing]

is only the last resistance

against this validity of the individual and an ever larger and larger number of individuals. One

can see plainly how that which spiritual science shows is also proved everywhere in these

significant points. We talk of associations which are necessary in the economic life, and use a

particular thinking for this. This has developed in the culture of the West from letting thoughts

associate. If one could take what

John Stuart Mill

does with logic, if one could remove those

thoughts from that sphere and apply them to the economic life, they would fit there. The

associations which would then come in there would be exactly those which do not fit into

psychology. Even in what appears in the area of human development, spiritual science follows

reality.

Thus spiritual science, if fully aware of the

seriousness of the present world situation, knows what a great battle is taking place between the

threefold social impulse that can come from spiritual science and that which throws itself

against this threefoldness as the wave of Bolshevism, which would lead to great harm (Unheil)

amongst humanity. And there is no third element other than these two. The battle has to take

place between these two. People must see this! Everything else is already decadent. Whoever looks

with an open mind at the conditions in which we are placed, must conclude that it is essential

today to gather all our forces together so that this whole terrible Ahrimanic affair can be

repulsed.

This building stands here,

[19]

incomplete though it is for the time being. Today we cannot get from the Central countries that

which for the most part, and in addition to what has come to us from the neutral states, has

brought this building to this stage. We must have contributions from the countries of the former

Entente. Understanding must be developed here for what is to become a unified culture containing

spirit, politics and economics. For people must get away from a one:sided tendency and must

follow those who also understand something of politics and economics, who do not work only in

dialectics, but, also being engaged with economic impulses, have insight into the spiritual, and

do not want to create states in which the State itself can run the economy. The Western peoples

will have to realize that something else must evolve in addition to the special gift they will

have in the future with regard to forming economic associations. The skill in forming

associations has so far been applied at the wrong end, i.e. in the field of Psychology. What must

evolve is understanding of the political-state element, which has other sources than the economic

life, and also of the spiritual element. But at present the Central countries lie powerless, so

people in the Western regions — one could not expect this of the Orient — will have

to see what the Purpose of this building is! It is necessary for us to consider What must be done

so that real provision is made for a new culture that should be presented everywhere in the

university education of the future — here we have to show the way. In the foundation of the

Waldorf Schools the culture has proved to be capable of bringing light into primary education.

But for this we need the understanding support of the widest circles.

Above all we need the means. For everything which,

in a higher or lower sense, is called a school, we need the frame of mind I have already tried to

awaken at the opening of the Waldorf School in Stuttgart.

[20]

I said in my

opening speech there: `This is one Waldorf school. It is well and good that we have it,

but for itself it is nothing; it is only something if, in the next quarter of a year, we build

ten such Waldorf schools and then others'. The world did not understand this, it had no money for

such a thing. For it rests on the standpoint: Oh, the ideals are too lofty, too pure for us to

bring dirty money to them; better to keep it in our pockets; that's the proper place for dirty

money. The ideals, oh, they're too pure, one can't contaminate them with money! Of course, with

purity of this kind the embodiment of ideals cannot be attained, if dirty money is not brought to

them. And thus we have to consider that, up to now, we have stopped at one Waldorf school which

cannot progress properly because in the autumn we found ourselves in great money difficulties.

These have been obviated for the time being, but at Easter we shall be faced with them again. And

then, after a comparatively short time, we will ask: Should we give up? And we shall have to give

up if, before then, an understanding is not forthcoming which dips vigorously into its

pockets.

It is thus a matter of awakening understanding in

this respect. I don't believe that much understanding would arise if we were to say that we

wanted something for the building in Dornach, or some such thing — as has been shown

already. But — and one still finds understanding for this today — if one wants to

create sanatoria or the like, one gets money, and as much as one wants! This is not exactly what

we want — we don't want to build a host of sanatoria — we agree fully with creating

them as far as they are necessary; but here it is a matter, above all, of nurturing that

spiritual culture whose necessity will indeed prove itself through what this course

[21]

I has attempted to accomplish. This is what I tried to suggest, to give a stimulus

to what I expressed here a few days ago, in the words 'World Fellowship of Schools'

(Weltschulverein).

[22]

Our German friends have departed but it is not a

question of depending on them for this 'World Fellowship'. It depends on those who, as friends,

have come here, for the most part from all possible regions of the non-German world — and

who are still sitting here now — that they understand these words 'World Fellowship of

Schools' because it is vital that we found school upon school in all areas of the world out of

the pedagogical spirit which rules in the Waldorf School. We have to be able to extend this

school until we are able to move into higher education of the kind we are hoping for here. For

this, however, we have to be in a position to complete this building and everything that belongs

to it, and be constantly able to support that which is necessary in order to work here; to be

productive, to work on the further extension of all the separate sciences in the spirit of

spiritual science.

People ask one how much money one needs for all

this. One cannot say how much, because there never is an uppermost limit. And, of course, we will

not be able to found a World Fellowship of Schools simply by creating a committee of twelve or

fifteen or thirty people who work out nice statutes as to how a World Fellowship of Schools of

this kind should work. That is all pointless. I attach no value to programmes or to statutes but

only to the work of active people who work with understanding. It will be possible to establish

this World Fellowship — well, we shall not be able to go to London for some time — in

the Hague or some such place, if a basis can be created, and by other means if the friends who

are about to go to Norway or Sweden or Holland, or any other country — England, France,

America and so on — awaken in every human being whom they can reach the well-founded

conviction that there has to be a World Fellowship of Schools. It ought to go through the world

like wildfire that a World Fellowship must arise to provide the material means for the spiritual

culture that is intended here.

If one is able in other matters, as a single

individual, to convince possibly hundreds and hundreds of people, why should one not be able in a

short time — for the decline is happening so quickly that we only have a short time —

to have an effect on many people as a single individual, so that if one came to the Hague a few

weeks later one would see how widespread was the thought that: 'The creation of a World

Fellowship of Schools is necessary, it is just that there are no means for it.' What we are

trying to do from Dornach is an historical necessity. One will only be able to talk of the

inauguration of this World Fellowship of Schools when the idea of it already exists. It is simply

utopian to set up committees and found a World Fellowship — this is pointless! But to work

from person to person, and to spread quickly the realization, the well-founded realization, that

it is so necessary — this is what must precede the founding. Spiritual science lives in

realities. This is why it does not get involved with proposals of schemes for a founding but

points to what has to happen in reality — and human beings are indeed realities — so

that such a thing has some prospects.

So what is important here is that we finally learn

from spiritual science how to stand in real life. I would never get involved with a simply

utopian founding of the World Fellowship of Schools, but would always be of the opinion that this

World Fellowship can only come about when a sufficiently large number of people are convinced of

its necessity. It must be created so that what is necessary for humanity — it has already

proved to be so from our course here — can happen. This World Fellowship of Schools must be

created.

Please see what is meant by this Fellowship in all

international life, in the right sense! I would like, in this request, to round off today what,

in a very different way in our course, has spoken to humanity through those who were here and of

whom we have the hope and the wish that they carry it out into the world. The World Fellowship of

Schools can be the answer of the world to what was put before it like a question; a question

taken from the real forces of human evolution, that is, human history. So let what can happen for

the World Fellowship of Schools, in accordance with the conviction you have been able to gain

here, happen! In this there rings out what I wanted to say today.

Notes:

1. These were the lectures given by Dr Karl Heyer on 14, 15 and 16 October

1920, during the first course of the School of Anthroposophy at the

Goetheanum

with the theme:

'The Science of History and History from the Viewpoint of Anthroposophy'

('Anthroposophische Betrachtungen Ober die Geschichtswissenschaft und aus der Geschichte').

These are printed in

Kultur und Erziehung

(the third volume of the Courses of the School of Anthroposophy),

Stuttgart, 1921. Return

2. See Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835):

Über die Aufgabe des Geschiclztsschreibens

(The Task of the Historian)

in Volume IV of Humboldt's Works published by Leitzman, Berlin 1905 (see pages 35-56).

Some relevant passages taken from these are as follows:

"The business of the historian, in the last but simplest analysis, is to

portray the striving of an idea to attain existence in reality. For it is not always that it

succeeds in this at the first attempt; and it is not so rare that the idea degenerates

because it is unable to master in a pure way the matter counteracting it."

"The truth of everything that happens lies in the addition of the

above-mentioned invisible part of every fact, and thus the history writer must add this to

the events. Seen from this angle he is self-acting and even creative — not, indeed, by

producing what does not already exist, but by forming out of his own inner strength that

which, as it is in reality, he could not perceive through mere receptivity. In different

ways, but just like the poet, he must in himself transform the scattered fragments into a

whole."

"It may seem dubious to allow the realm of the history writer and that of

the poet to meet, even at only one point. But the activity of both is undeniably related. For

if the historian, like the poet, can achieve truth in his presentation of past events only by

completing and linking the incomplete and disjointed elements of direct observation, then he

does so, like the poet, only through imagination. Because, however, he places imagination

subordinate to experience and the fathoming of reality, there is a difference here which

cancels out all danger. Imagination does not work, at this lower position, as pure

imagination, and is therefore more properly called an intuitive faculty and a talent for

finding links."

"Of necessity, therefore, the historian too, must strive; not, like the

poet, to give his material over to the dominion of the form of necessity but to hold steadily

in consciousness the ideas which are its laws, because, permeated only by, these, he can then

find their trace in the pure research of the real in its reality."

"The historian encompasses all the threads of earthly activity and all

varieties of supersensible ideas; the sum-total of existence, more or less, is the object of

his work and he must therefore also follow all avenues of the mind and spirit. Speculation,

experience and poetry, however, are not separate, opposed and mutually-limiting activities of

the mind, but different planes of its radiance."

"Apart from the fact that history, like every scientific activity, serves

many subsidiary purposes, work on history is no less a free art, complete in itself, than

philosophy and poetry."

"Just as philosophy strives for the first foundation of things, and art

for the ideal of beauty, so history strives for a picture of human destiny in faithful truth,

living abundance and pure clarity that are perceived by the warm inner-being

[of the historian]

in such a way that his personal views, feelings and demands are lost and dissolved

away. It is the final purpose of the history-writer to awaken and nourish this mood, which,

however, he only attains when he pursues for his fellow human beings the simple presentation

of past events with conscientious faithfulness."

Return

3. See the final words of Rudolf Steiner, on 16 October 1920, after the

close of the first course of the Anthroposophical School, in

Die Kunst der Rezitation and Deklamation

(First Edition) Dornach, 1928, page 118. Return

4. See

i>Geschictliche Symptomatologie

(GA 185), nine lectures given in Dornach in 1918, only two of which are translated in

From Symptom to Reality in Modern History. Return

5. See

Bedeutende Fordnis durch ein einziges geistreiches Wort

in Goethes

Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften,

edited and with a commentary by Rudolf

Steiner in Kürschner's

Deutsche National-Literatur,

Volume II, page 34 (GA lb). Goethe says here:

"I do not rest until I find a significant point from which a great deal

can be deduced or, rather, which of its own will brings forth a great deal and presents this

to me, and which I then, with attention and receptivity, work on further faithfully and

carefully. If, in my experience, I find some phenomenon which I cannot deduce, I simply let

it lie as a problem; and I have found, in my long life, this way of doing things to be very

beneficial. For when I was not able for a long time to unravel the origin or connection of

some phenomenon but had to put it to one side, I found that, years later, it all suddenly

became clear in the most beautiful way."

Return

6. Alcuin (also Alhuin or Alchwin, i.e. 'Friend of the Temple') was rector

of the monastery school at York around 735 to 804. In 782 he followed the summons of

Charlemagne and took on the headship of the court school. He encouraged the sciences in the

monasteries and raised to the central seat of the sciences the monastery school of St Martin at

Tours, which he founded and whose Abbot he became in 796.

The debate with the Greek is described in Karl Werner's book

Alcuin and sein Jahrhundert

(Alcuin and His Century)

Vienna 1881, Chapter 11. page 166, as follows:

Thus Charlemagne once wanted to know from Alcuin what should be made of

the view of a Greek scholar, who presumably was a member of a Byzantine legation at

Charlemagne's court, who had expressed the opinion to the emperor that Christ had paid the

expiation for our sins to death. Alcuin found this manner of expression and the idea behind

it to be inadmissible, for Christ was not — death's debtor and could not become so

— the price of our redemption was paid by Christ to our divine Father, to whom, in

dying, He commended His soul. Death

[so Alcuin argued]

is in no way a reality of being and

substance but, to his way of thinking, was something purely negative, the mere absence or

'Carence' (Church Latin: the interval before benefits become available) of life; it is

nothing existing in itself, and thus cannot receive anything, no payment can be paid to it.

On the contrary, in the person of Christ, death itself, which God did not create, became the

ransom for our debt and won life for us thereby, which He Himself gives us in His saviour

power.'

Return

7. Rudolf Steiner drew attention at different times to the fact that the

content of the writings of 533 AD, attributed to Dionysius the Areopagite, do indeed stem

from the person of this name mentioned in

The Acts of the Apostles 17, 34.

See the lectures on 17 and 25 March 1907 in

Christianity Began as a Religion and

Festivals of the Seasons

respectively. Return

8. Johannes Scotus Erigena (c. 810–877) translator of the writings of

Dionysius the Areopagite into Latin (see Return

9. Nicolaus of Cusa (or Kures) (1401–1464), cardinal. Return

10.

Immanuel Kant

(1724–1804):

Critique of Pure Reason,

1781;

Prolegemena,

1783. Return

11. See

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

(1762–1814)

Erste und zweite Einleitung in die Wissenschaftslehre und Verstwh einer neuen Darstellung der

Wiyenschaftslehre

(First and Second Introduction into the Doctrine of Knowledge and an Attempt at a New

Presentation of the doctrine of Knowledge). Return

12.

Grenzen der Naturerkenntnis

(Limits to a Knowledge of Nature

(GA 322) — eight lectures given during the first course

(Hochschulkurs)

of the School of Spiritual Science in Dornach, 27 September to 3

October 1920 (GA 322). Return

13. Baron Christian von Wolff, philosopher and mathematician,

Vernünftige Gedanken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen

überhaupt,

1719. Return

14. David Hume (1711–1776), philosopher. Return

15.

Herbert Spencer

(1820–1903), philosopher. Return

16. John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), philosopher. Return

17. See Rudolf Steiner,

Towards Social Renewal,

1919, (GA 23). Return

18. In the third week of the first course (of the School of Spiritual

Science), Dr Carl Unger (1822–1929) gave lectures under the title of 'Rudolf Steiner's

Works'. These six lectures, edited by Unger, can be found in Volume I of

Carl Unger's Writings,

Stuttgart, 1964. Return

19. The first Goetheanum building, begun in 1913, was already put into use

in 1920, although still under construction supervised by Rudolf Steiner and with the interior

not yet finished. On New Year's Eve 1922–3 it was destroyed by fire. Return

20. The Free Waldorf School was founded in Stuttgart in the spring of 1919 by Dr

Emil Molt

for the children, to begin with, of the employees of the Waldorf-Astoria

cigarette factory. The school was under the supervision of Rudolf Steiner who appointed the

teachers and gave the preparatory seminar courses. Return

21. The first anthroposophical course of the Free School for Spiritual

Science took place at the Goetheanum from 26 September to 16 October 1920. See also notes

1,3,12, and 18. Return

22. I.e., a form of international support body for Waldorf Schools. Rudolf

Steiner suggested the founding of a World Fellowship of Schools during an assembly of teachers

on 16 October 1920. There is no available transcript of this talk. Return

|