4th Lecture

The New Spirituality

and the Christ Expereience of the Twentieth Century

Lecture 3

Dornach,

24 October, 1920

As early as 1891 I drew attention

[1]

to the relation between Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters

[2]

and Goethe's

Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily.

[3]

I would like today to point to a certain connection between what I gave yesterday as the

characteristic of the civilization of the Central-European countries in contrast to the Western

and Eastern ones and what arises in quite a unique way in

Goethe

and

Schiller.

I characterized,

on the one hand, the seizure of the human corporality by the spirits of the West and, on the

other hand, the feeling of those spiritual beings who, as imaginations, as spirits of the East,

work inspiringly into Eastern civilization. And one can notice both these aspects in the leading

personalities of Goethe and Schiller. I will only point out in addition how in Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters

he seeks to characterize a human soul-constitution which shows a

certain middle mood between one possibility in the human being — his being completely given

over to instincts, to the sensible-physical — and the other possibility — that of

being given over to the logical world of reason. Schiller holds that, in both cases, the human

being cannot come to freedom. For if he has completely surrendered himself to the world of the

senses, to the world of instincts, of desires, he is given over to his bodily-physical nature and

is unfree. But he is also unfree when he surrenders himself completely to the necessity of

reason, to logical necessity; for then he is coerced under the tyranny of the laws of logic. But

Schiller wants to point to a middle state in which the human being has spiritualized his

instincts to such a degree that he can give himself up to them without their dragging him down,

without their enslaving him, and in which, on the other hand, logical necessity is taken up into

sense perception

(sinnliche Anschauen),

taken up into personal desires

(Triebe),

so that these logical necessities do not also enslave the human being.

Schiller finds this middle state in the condition

of aesthetic enjoyment and aesthetic creation, in which the human being can come to true

freedom.

It is an extremely important fact that Schiller's

whole treatise arose out of the same European mood as did the French Revolution. The same thing

which, in the West, expressed itself tumultuously as a large political movement orientated

towards external upheaval and change also moved Schiller — but moved him in such a way that

he sought to answer the question: What must the human being do in himself in order to become a

truly free being? In the West they asked: How must the external social conditions be changed so

that the human being can become free? Schiller asked: What must the human being become in himself

so that, in his constitution of soul, he can live in

(darleben)

freedom? And he sees

that if human beings are educated to this middle mood they will also represent a social community

governed by freedom. Schiller thus wishes to realize a social community in such a way that free

conditions are created through

[the inner nature of]

human beings and not through outer measures.

Schiller came to this composition of his

Aesthetic Letters

through his schooling in Kantian philosophy. His was indeed a highly

artistic nature, but in the 1780s and the beginning of the 1790s he was strongly influenced by

Kant and tried to answer such questions for himself in a Kantian way

(im Kantischen Sinne).

Now the

Aesthetic Letters

were written just at the time when Goethe and Schiller were founding the magazine

Die Horen

(The Hours)

and Schiller lays the Aesthetic Letters before Goethe.

Now we know that Goethe's soul-configuration was

quite different from Schiller's. It was precisely because of the difference of their

soul-constitutions that these two became so close. Each could give to the other just that which

the other lacked. Goethe now received Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters

in which Schiller

wished to answer the question: How can the human being come inwardly to a free inner constitution

of soul and outwardly to free social conditions? Goethe could not make much of Schiller's

philosophical treatise. This way of presenting concepts, of developing ideas, was not unfamiliar

to him. Anyone who, like myself, has seen how Goethe's own copy of Kant's

Critique of Pure Reason

is filled with underlinings and marginal comments knows how Goethe had really studied

this work of Kant's which was abstract, but in a completely different sense. And just as he seems

to have been able to take works such as these purely as study material, so, of course, he could

also have taken Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters.

But this was not the point. For Goethe

this whole construction of the human being — on the one hand logical necessity and on the

other the senses with their sensual needs, as Schiller said, and the third, the middle condition

— for Goethe this was all far too cut and dried, far too simplistic. He felt that one could

not picture the human being so simply, or present human development so simply, and thus he wrote

to Schiller that he did not want to treat the problem, this whole riddle, in such a

philosophical, intellectual form, but more pictorially. Goethe then treated this same problem in

picture form — as reply, as it were, to Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters

— in his

Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily

by presenting the two realms on

this and on the far side of the river, in a pictorial, rich and concrete way; the same thing that

Schiller presents as sense-life and the life of reason. And what Schiller characterizes

abstractly as the middle condition, Goethe portrays in the building of the temple in which rule

the King of Wisdom (the Golden King), the King of Semblance (the Silver King), the King of Power

(the Copper King) and in which the Mixed King falls to pieces. Goethe wanted to deal with this in

a pictorial way. And we have, in a certain sense, an indication — but in the Goethean way

— of the fact that the outer structure of human society must not be monolithic but must be

a threefoldness if the human being is to thrive in it. What in a later epoch had to emerge as the

threefold social order is given here by Goethe still in the form of an image. Of course, the

threefold social order does not yet exist but Goethe gives the form he would like to ascribe to

it in these three kings; in the Golden, the Silver, and the Copper King. And what cannot hold

together he gives in the Mixed King.

But it is no longer possible to give things in this

way. I have shown this in my first Mystery Drama

[4]

which, in essence, deals with the same theme but in the way required by the beginning of the

twentieth century, whereas Goethe wrote his

Fairy-tale

at the end of the eighteenth century.

Now, however, it is already possible to indicate in

a certain way — even though Goethe had not himself yet done so — how the Golden King

would correspond to that aspect of the social organism which we call the spiritual aspect: how

the King of Semblance, the Silver King, would correspond to the political State: how the King of

Power, the Copper King, would correspond to the economic aspect, and how the Mixed King, who

disintegrates, represents the 'Uniform State' which can have no permanence in itself.

This was how, in images, Goethe pointed to what

would have to arise as the threefold social order. Goethe thus said, as it were, when he received

Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters:

One cannot do it like this. You, dear friend, picture the

human being far too simplistically. You picture three forces. This is not how it is with the

human being. If one wishes to look at the richly differentiated inner nature of the human being,

one finds about twenty forces — which Goethe then presents in his twenty archetypal

fairy-tale figures — and one must then portray the interplay and interaction of these

twenty forces in a much less abstract way.

Thus at the end of the eighteenth century we have

two presentations of the same thing. One by Schiller, from the intellect as it were, though not

in the usual way that people do things from the intellect, but such that the intellect is

permeated here with feeling and soul, is permeated by the whole human being. Now there is a

difference between some dry, average, professional philistine presenting something on the human

being in psychological terms, where only the head thinks about the matter, and Schiller, out of

an experience of the whole human being, forming for himself the ideal of a human constitution of

soul and thereby only transforming into intellectual concepts what he actually feels.

It would be impossible to go further on the path

taken by Schiller using logic or intellectual analysis without becoming philistine and abstract.

In every line of these

Aesthetic Letters

there is still the full feeling and sensibility

of Schiller. It is not the stiff Königsberg approach of

Immanuel Kant

with dry concepts; it

is profundity in intellectual form transformed into ideas. But should one take it just one step

further one would come into the intellectual mechanism that is realized in the usual science of

today in which, basically, behind what is structured and developed intellectually, the human

being has no more significance. It thus becomes a matter of no importance whether Professor A or

D or X deals with the subject because what is presented does not arise from the whole human

being. In Schiller everything still has a totally personal

(urpersönlich)

nature,

even into the intellect. Schiller lives there in a phase — indeed, in an evolutionary point

of the modern development of humanity which is of essential importance — because Schiller

stops just short of something into which humanity later fell completely.

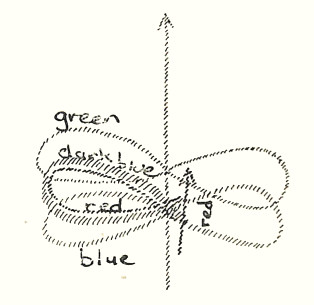

Let us show diagramatically what might be meant

here. One could say: This is the general tendency of human evolution (arrow pointing upwards).

Yet it cannot go

[straight]

like this — portrayed only schematically — but loops

round into a lemniscate (blue). But it cannot go on like that — there must, if evolution

takes this course, be continually new impulses

Antriebe)

which move the lemniscates up along the line.

Schiller, having arrived at this point here (see diagram), would have gone

into a dark blue, as it were, of mere abstraction, of intellectuality, had he proceeded further

in objectifying what he felt inwardly. But he drew a halt and paused with his forms of reasoning

just at that point at which the personality is not lost. Thus, this did not become blue but, on a

higher level of the Personality — which I will colour with red (see diagram) — was

turned into green.

Thus one can say: Schiller held back with his

intellectuality just before that point at which intellectuality tries to emerge in its purity.

Otherwise he would have fallen into the usual intellect of the nineteenth century. Goethe

expressed the same thing in images, in wonderful images, in his

Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily.

But he, too, stopped at the images. He could not bear these pictures

to be in any way criticized because, for him, what he perceived and felt about the individual

human element and the social life, did simply present itself in such pictures. But he was allowed

to go no further than these images. For had he, from his standpoint, tried to go further he would

have come into wild, fantastic daydreams. The subject would no longer have had definite contours;

it would no longer have been applicable to real life but would have risen above and beyond it. It

would have become rapturous fantasy. One could say that Goethe had to avoid the other chasm, in

which he would have come completely into a fantastic red. Thus he adds that element which is

non-personal — that which keeps the pictures in the realm of the imaginative — and

thereby came also to the green.

Expressing it schematically, Schiller had, as it

were, avoided the blue, the Ahrimanic-intellectuality; Goethe had avoided the red, excessive

rapturousness, and kept to concrete imaginative pictures.

As a human being of Central Europe, Schiller had

con-fronted the spirits of the West. They wanted to lead him astray into the solely intellectual.

Kant had succumbed to this. I spoke about this recently

[5]

and indicated how Kant had succumbed to the intellectuality of the West through

David Hume.

Schiller had managed to work himself clear of this even though he allowed himself to be taught by

Kant. He stayed at the point that is not mere intellectuality.

Goethe had to do battle with the other spirits, with

the spirits of the East, who pulled him towards imaginations. Because at that time spiritual

science was not yet present on the earth he could not go further than to the web of imaginations

in the

Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily.

But even here he managed to

remain within firm contours. He did not go off into wild fantasy or ecstasies. He gave himself a

new and fruitful stimulus through his journey to the South where much of the legacy from the

Orient was still preserved. He learnt how the spirits of the East still worked here as a late

blossoming of oriental culture; in Greek art as he construed this for himself from Italian works

of art. It can therefore be said that there was something quite unique in this bond of friendship

between Schiller and Goethe. Schiller had to battle with the spirits of the West; he did not

yield to them but held back and did not fall into mere intellectuality. Goethe had to battle with

the spirits of the East; they tried to pull him into ecstatic reveries

zum Schwärmerischen).

He, too, held back; he kept to the images which he gives in his

Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily.

Goethe would have had either to

succumb to rapturous daydreams

(Schwärmerei)

or to take up oriental revelation.

Schiller would have had either to become completely intellectual or would have had to take

seriously what he became — it is well known that he was made a 'French citizen' by the

revolutionary government but that he did not take the matter very seriously.

We see here how, at an important point of European

development, these two soul-constitutions, which I have characterized for you, stand side by

side. They live anyway, so to speak, in every significant Central-European individuality but in

Schiller and Goethe they stand in a certain way simultaneously side by side. Schiller and Goethe

remained, as it were, at this point, for it just required the intercession of spiritual science

to raise the curve of the lemniscate (see diagram) to a higher level.

And thus, in a strange way, in Schiller's three

conditions — the condition of the necessity of reason, the condition of the necessity of

instincts and that of the free aesthetic mood — and in Goethe's three kings — the

Golden King, the Silver King, and the Copper King — we see a prefiguration of everything

that we must find through spiritual science concerning the threefold nature of the human being as

well as the threefold differentiation of the social community representing, as these do, the most

immediate and essential aims and problems of the individual human being and of the way human

beings live together.

These things direct us indeed to the fact that this

threefolding of the social organism is not brought to the surface arbitrarily but that even the

finest spirits of modern human evolution have already moved in this direction. But if there were

only the ideas about the social questions such as those in Goethe's

Fairy-tale

and nothing more one would never come to an impetus for actual outer action. Goethe was at the point

of overcoming mere revelations. In Rome he did not become a Catholic but raised himself up to his

imaginations. But he stopped there, with just pictures. And Schiller did not become a

revolutionary but a teacher of the inner human being. He stopped at the point where intellect is

still suffused with the personality.

Thus, in a later phase of European culture, there

was still something at work which can be perceived also in ancient times and most clearly, for

modern people, in the culture of ancient Greece. Goethe also strove towards this Greek element.

In Greece one can see how the social element is presented in myth — that is, also in

picture form. But the Greek myth, basically, Is image in the same way that Goethe's

Fairy-tale

is image. It is not possible with these images to work into the social

organism in a reforming way. One can only describe as an idealist, as it were, what ought to take

shape. But the images are too frail a structure to enable one to act strongly and effectively in

the shaping of the social organism. For this very reason the Greeks did not believe that their

social questions were met by remaining in the images of the myths. And it is here, when one

follows this line of investigation, that one comes to an important point in Greek

development.

One could put it like this: for everyday life,

where things go on in the usual way, the Greeks considered themselves dependant on their gods, on

the spirits of their myths. When, however, it was a matter of deciding something of great

importance, then the Greeks said: Here it is not those gods who work into imaginations and are

the gods of the myths that can determine the matter; here something real must come to light. And

so the Oracle arose. The gods were not pictured here merely imaginatively but were called upon

(veranlasst)

really to inspire people. And it was with the sayings of the Oracle that

the Greeks concerned themselves when they wanted to receive social impulses. Here they ascended

from imagination to inspiration, but an inspiration which they attained by means of outer nature.

We modern human beings must certainly also endeavour to lift ourselves up to inspiration; an

inspiration, however, that does not call upon outer nature in oracles but which rises to the

spirit in order to be inspired in the sphere of the spirit. But just as the Greeks turned to

reality in matters of the social sphere — just as they did not stop at imaginations but

ascended to inspirations — so we, too, cannot stop at imaginations but must rise up to

inspirations if we are to find anything for the well-being of human society in the modern

age.

And we come here to another point which is

important to look at. Why did Schiller and Goethe both stop at a certain point — the one on

the path towards the intellectual

(Verstandiges)

and the other on the path to the

imaginative? Neither of them had spiritual science; otherwise Schiller would have been able to

advance to the point of permeating his concepts in a spiritual-scientific way and he would then

have found: something much more real in his three soul-conditions than the three abstractions in his

Aesthetic Letters.

Goethe would have filled imagination with what speaks out in all

reality from the spiritual world and would have been able to penetrate to the forms of the social

life which wish to be put into effect from the spiritual world — to the spiritual element

in the social organism, the Golden King; to the political element in the social organism, the

Silver King; and to the economic element, the Bronze, the Copper, King.

The age in which Goethe and Schiller pressed

forward to these insights — the one in the

Aesthetic Letters

and the other in the

Fairy-tale

— was not yet able to go any further. For, in order to penetrate

further, there is something quite definite that must first be realized. People have to see what

becomes of the world if one continues along Schiller's path up to the full elaboration

(Ausgestaltung)

of the impersonally intellectual. The nineteenth century developed it to

being with in natural science and the second half of the nineteenth century already began to try

to realize it in outer public affairs. There is a significant secret here. In the human organism

what is ingested is also finally destroyed. We cannot simply go on eating but must also excrete;

the substance we take in has to meet with destruction, has to be destroyed, and has then to leave

the organism. And the intellectual is that which — and here comes a complication — as

soon as it gets hold of the economic life in the uniform State, in the Mixed King, destroys that

economic life.

But we are now living in the time in which the

intellect must evolve. We could not come to the development of the consciousness-soul in the

fifth post-Atlantean epoch without developing the intellect. And it is the Western peoples that

have just this task of bringing the intellect into the economic life. What does this mean? We

cannot order modern economic life imaginatively, in the way that Goethe did in his

Fairy-tale,

because we have to shape it through the intellect

(verständig).

Because in economics we cannot but help to go further along the path

which Schiller took, though in his case he went only as far as the still-personal outbreathing of

the intellect. We have to establish an economic life which, because it has to come from the

intellect, of necessity works destructively in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. In the present age

there is no economic life that could be run imaginatively like that of the Orient or the economy

of medieval Europe. Since the middle of the fifteenth century we have only had the possibility of

an economic life which, whether existing alone or mixed with the other limbs of the social

organism, works destructively. There is no other way. Let us therefore look on this economic life

as the side of the scales that would sink far down and therefore has to work destructively. But

there also has to be a balance. For this reason we must have an economic life that is one part of

the social organism, and a spiritual life which holds the balance, which builds up again. If one

clings today to the uniform State, the economic life will absorb this uniform State together with

the spiritual life, and uniform States like these must of necessity lead to destruction. And

when, like Lenin and Trotsky, one founds a State purely out of the intellect it must lead to

destruction because the intellect is directed solely to the economic life.

This was felt by Schiller as he thought out his

social conditions. Schiller felt: If I go further in the power of the intellect

(verständesmassiges Können)

I will come into the economic life and will have

to apply the intellect to it. I will not then be portraying what grows and thrives but what lives

in destruction. Schiller shrank back before the destruction. He stopped just at the point where

destruction would break in. People of today invent all sorts of social economic systems but are

not aware, because they lack the sensitivity of feeling for it, that every economic system like

this that they think up leads to destruction; leads definitely to destruction if it is not

constantly renewed by an independent, developing spiritual life which ever and ever again works

as a constructive

element in relation to the destruction, the excretion, of the economic

life. The working together of the spiritual limb of the social organism with the economic element

is described in this sense in my

Towards Social Renewal

(Kernpunkte der Sozialen

Frage).

[6]

If, with the modern intellectuality of the fifth

post-Atlantean epoch, people were to hold on to capital even when they themselves could no longer

manage it, the economic life itself would cause it to circulate. Destruction would inevitably

have to come. This is where the spiritual life has to intervene; capital must be transferred via

the spiritual life to those who are engaged in its administration. This is the inner meaning of

the threefolding of the social organism; namely that, in a properly thought out threefold social

organism, one should be under no illusion that the economic thinking of the present is a

destructive element which must, therefore, be continually counterbalanced by the constructive

element of the spiritual limb of the social organism.

In every generation, in the children whom we teach

at school, something is given to us; something is sent down from the spiritual world. We take

hold of this in education — this is something spiritual — and incorporate it into the

economic life and thereby ward off its destruction. For the economic life, if it runs its own

course, destroys itself. This is how we must look at things. Thus we must see how at the end of

the eighteenth century there stood Goethe and Schiller. Schiller said to himself: I must pull

back, I must not describe a social system which calls merely on the personal intellect. I must

keep the intellect within the personality, otherwise I would describe economic destruction. And

Goethe: I want sharply contoured images, not excessive vague ones. For if I were to go any

further along that path I would come into a condition that is not on the earth, that does not

take hold with any effect on life itself. I would leave the economic life below me like something

lifeless and would found a spiritual life that is incapable of reaching into the immediate

circumstances of life.

Thus we are living in true Goetheanism when we do

not stop at Goethe but also share the development in which Goethe himself took part since 1832. I

have indicated this fact — that the economic life today continually works towards its own

destruction and that this destruction must be continually counterbalanced. I have indicated this

in a particular place in my

Towards Social Renewal.

But people do not read things

properly. They think that this book is written in the same way most books are written today

— that one can just read it through. Every sentence in a book such as this, written out of

practical insight, requires to be thoroughly thought through!

But if one takes these two things

[Goethe's

Fairy-tale

and Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters],

Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters

were little understood in the time that followed them. I have often spoken about

this. People gave them little attention. Otherwise the study of Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters

would have been a good way of coming into what you find in my

Knowledge of the Higher Worlds — How is it Achieved?

Schiller's

Aesthetic Letters

would be a

good preparation for this. And likewise, Goethe's

Fairy-tale

could also be the preparation for acquiring that configuration of thinking

(Geisteskonfiguration)

which can arise not merely from the intellect but from still deeper forces, and which would be

really able to understand something like

Towards Social Renewal.

For both Schiller and

Goethe sensed something of the tragedy of Central European civilization — certainly not

consciously, but they sensed it nevertheless. Both felt — and one can read this everywhere

in Goethe's conversations with Eckermann, with Chancellor von Müller

[7],

and in numerous other comments by Goethe — that if something like a new impulse from the

spirit did not arise, like a new comprehension of Christianity, then everything must go into

decline. A great deal of the resignation which Goethe felt in his later years is based, without

doubt, on this mood.

And those who, without spiritual science, have

become Goetheanists feel how, in the very nature of German Central Europe, this singular working

side by side of the spirits of the West and the spirits of the East is particularly evident. I

said yesterday that in Central European civilization the balance sought by later Scholasticism

between rational knowledge and revelation is attributable to the working of the spirits of the

West and the spirits of the East. We have seen today how this shows itself in Goethe and

Schiller. But, fundamentally, the whole of Central European civilization wavers in the whirlpool

in which East and West swirl and interpenetrate one another. From the East the sphere of the

Golden King; from the West the sphere of the Copper King. From the East, Wisdom; from the West,

Power. And in the middle is what Goethe represented in the Silver King, in Semblance; that which

imbues itself with reality only with great difficulty. It was this semblance-nature of Central

European civilization which lay as the tragic mood at the bottom of Goethe's soul. And Herman

Grimm, who also did not know spiritual science, gave in a beautiful way, out of his sensitive

feeling for Goethe whom he studied, a fine characterization of Central-European civilization. He

saw how it had the peculiarity of being drawn into the whirlpool of the spirits of the East and

the spirits of the West. This was the effect of preventing the will from coming into its own and

leads to the constantly vacillating mood of German history. Herman Grimm

[8]

puts

it beautifully when he says: 'To Treitschke German history is the incessant striving towards

spiritual and political unity and, on the path towards this, the incessent interference by our

own deepest inherent peculiarities.' This is what

Herman Grimm

says, experiencing himself as a

German. And he describes this further as 'Always the same way in our nature to oppose where we

should give way and to give way where resistance is called for. The remarkable forgetting of what

has just past. Suddenly no longer wanting what, a moment ago, was vigorously striven for. A

disdain for the present, but strong, indefinite hope. Added to this the tendency to give

ourselves over to the foreigner and, no sooner having done so, then exercising an unconscious,

determining

(massgebende)

influence on the foreigners to whom we had subjected ourselves.'

When, today, one has to do with Central European

civilization and would like to arrive at something through it, one is everywhere met by the

breath of this tragic element which is betrayed by the whole history of the German, the Central

European element, between East and West. It is everywhere still so today that, with Herman Grimm,

one can say: There is the urge to resist where one should give way and to give way where

resistance is needed.

This is what arises from the vacillating human

beings of the Centre; from what, between economics and the reconstructing spirit-life, stands in

the middle as the rhythmical oscillating to and fro of the political. Because the civic-political

element has celebrated its triumph in these central countries, it is here that a semblance lives

which can easily become illusion. Schiller, in writing his

Aesthetic Letters,

did not

want to abandon semblance. He knew that where one deals purely with the intellect, one comes into

the destruction of the economic life. In the eighteenth century that part was destroyed which

could be destroyed by the French Revolution; in the nineteenth century it would be much worse.

Goethe knew that he must not go into wild fantasies but keep to true imagination. But in the

vacillation between the two sides of this duality, which arises in the swirling, to and fro

movement of the spirits of the West and of the East, there is easily generated an atmosphere of

illusion. It does not matter whether this illusionary atmosphere emerges in religion, in politics

or in militarism; in the end it is all the same whether the ecstatic enthusiast produces some

sort of mysticism or enthuses in the way Ludendorff

[9]

did without standing on

the ground of reality. And, finally, one an also meet it in a pleasing way. For the same place in

Herman Grimm which I just read out continues as follows: 'You can see it today: no one seemed to

be so completely severed from their homeland as the Germans who became Americans, and yet

American life, into which our emigrants dissolved, stands today under the influence of the German

spirit.'

Thus writes the brilliant Herman Grimm in 1895 when

it was only out of the worst illusion that one could believe that the Germans who went to America

would give American life a German colouring. For already, long before this, there had been

prepared what then emerged in the second decade of the twentieth century: that the American

element completely submerged what little the Germans had been able to bring in.

And the illusionary nature of this remark by Herman

Grimm becomes all the greater when one finally bears in mind the following. Herman Grimm makes

this comment from a Goethean way of thinking

(Gesinnung),

for he had modelled himself

fully on Goethe. But he had a certain other quality. Anyone who knows Herman Grimm more closely

knows that in his style, in his whole way of expressing himself, in his way of thinking, he had

absorbed a great deal of Goethe, but not Goethe's real and penetrating quality — for

Grimm's descriptions are such that what he actually portrays are shadow pictures, not real human

beings. But he has something else in him, not just Goethe. And what is it that Herman Grimm has

in himself? Americanism! For what he had in his style, in his thought-forms, apart from Goethe he

has from early readings of Emerson. Even his sentence structure, his train of thought, is copied

from the American, Emerson.

[10]

Thus, Herman Grimm is under this double illusion,

in the realm of the Silver King of Semblance. At a time when all German influence has been

expunged from America he fondly believes that America has been Germanized, when in fact he

himself has quite a strong vein of Americanism in him.

Thus there is often expressed in a smaller, more

intimate context what exists in a less refined form in external culture at large. A crude

Darwinism, a crude economic thinking, has spread out there and would in the end, if the

threefolding of the social organism fails to come, lead to ruin — for an economic life

constructed purely intellectually must of necessity lead to ruin. And anyone who, like Oswald

Spengler,

[11]

thinks in the terms of this economic life can prove

scientifically that at the beginning of the third millenium the modern civilized world —

which today is actually no longer so very civilized — will have had to sink into the most

desolate barbarity. For Spengler knows nothing of what the world must receive as an impulse, as a

spiritual impulse.

But the spiritual science and the

spiritual-scientific culture which not only wishes to enter, but must enter, the world

today still has an extremely difficult task getting through. And everywhere those who wish to

prevent this spiritual science from arising assert themselves. And, basically, there are only a

few energetic workers in the field of spiritual science whereas the Others, who lead into the

works of destruction, are full of energy.

One only has to see how people of today are

actually completely at a loss in the face of what comes up in the life of Present civilization.

It is characteristic, for instance, how a newspaper of Eastern Switzerland carried articles on my

lectures on

The Boundaries of Natural Science

during the course at the School of

Spiritual Science. And now, in the town where the newspaper is published, Arthur Drews

[12],

the copy-cat of

Eduard von Hartmann,

holds lectures in which he has never done

anything more than rehash Eduard von Hartmann, the philosopher of the unconscious.

[13]

In the case of Hartmann it is interesting. In the case of the rehasher it is, of

course, highly superfluous. And this philosophical hollow-headedness working at Karlsruhe

University is now busying itself with anthroposophically-orientated spiritual science.

And how does the modern human being — I would

particularly like to emphasize this — confront these things? Well, we have listened to one

person, we now go and listen to someone else. This means that, for the modern human being, it is

all a matter of indifference, and this is a terrible thing. Whether the rehasher of Eduard von

Hartmann, Arthur Drews, has something against Anthroposophy or not is not the important point

— for what the man can have against Anthroposophy can be fully construed beforehand from

his books, not a single sentence need be left out. The significant thing is that people's

standpoint is that one hears something, makes a note of it, and then it is over and done with,

finished! All that is needed to come to the right path is that people really go into the matter.

But people today do not want to be taken up with having to go into something properly. This is

the really terrible and awful thing; this is what has already pushed people so far that they are

no longer able to distinguish between what is speaking of realities and what writes whole books,

like those of Count Hermann Von Keyserling,

[14]

in which there is not one

single thought, just jumbled-together words. And when one longs for something to be taken up

enthusiastically — which would, of itself, lead to this hollow word-skirmishing being

distinguished from what is based on genuine spiritual research — one finds no one who

rouses himself, makes a stout effort and is able to be taken hold of by that which has substance.

This is what people have forgotten — and forgotten thoroughly — in this age in which

truth is not decided according to truth itself, but in which the great lie walks among men so

that in recent years individual nations have only found to be true what comes from them and have

found what comes from other nations to be false. The disgusting way that people lie to each other

has fundamentally become the stamp of the public spirit. Whenever something came from another

nation it was deemed untrue. If it came from one's own nation it was true. This still echoes on

today; it has already become a habit of thought. In contrast, a genuine, unprejudiced devotion to

truth leads to spiritualization. But this is basically still a matter of indifference for modern

human beings.

Until a sufficiently large number of people are

willing to engage themselves absolutely whole-heartedly for spiritual science, nothing beneficial

will come from the present chaos. People should not believe that one can somehow progress by

galvanizing the old. This 'old' founds 'Schools of Wisdom' on purely hollow words. It has

furnished university philosophy with the Arthur Drews's who, however, are actually represented

everywhere, and yet humanity will not take a stand. Until it makes a stand in all three spheres

of life — in the spiritual, the political and the economic spheres — no cure can come

out of the present-day chaos. It must sink ever deeper!

Notes:

1. See Rudolf Steiner's own review (GA 51) of his lecture to the Vienna Goethe

Association

(Wiener Goetheverein)

on 27 November 1891 entitled

Über das Geheimnis in Goethes Rätselmarchen in den 'Unterhaltu deutscher Ausgewanderter'

(On the Secret in Goethe's Enigmatic Fairy Tale in 'Conversations of German Emigrants)

in

Literarisches Frühhwerk,

Vol III, Book IV, Dornach, 1942. See also

Goethe's Standard of the Soul

(Goethes Geistesart in ihrer Offenbarung durch seine 'Faust' und durch sein

'Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der Lilie')

(GA 22). Return

2. See

On the Aesthetic Education of Man

published in 1795 in the

Die Horen.

This work arose from letters sent by Schiller to the Duke of Augustenburg

between 1793 and 1795. Return

3. Published in the

Die Horen

in 1795 as the close to the short story

Conversations of German Emigrants. Return

4. See

The Portal of Initiation — A Rosicrucian Mystery,

1910, in

Four Mystery Dramas,

(GA 14). Return

5. See Lecture One of this volume. Return

6. See

Towards Social Renewal,

1919, (GA 23). For what follows on here,

see Chapter Two. Return

7. See, for example, the conversation with Chancellor von Müller on 8 June

1830 and that with Eckermann on 11 March 1832. Return

8. Herman Grimm (1828–1902). The quotations are from his essay

Heinrich von Treitschke's German History

(Heinrich von Treitschhes Deutsche Geschichte)

in

Contributions to German Cultural History,

(Beitrage zur Deutschen Kultur-geschichte)

Berlin, 1897, page. 5 Return

9. Erich Ludendorff (1865–1937), German general. Return

10. Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), American writer and philosopher. Return

11. Reference is made here to

Oswald Spengler

(1880–1936) and his work

Der Untergang des Abendlandes

(The Decline and Fall of the Occident),

the first part of which was published in 1918. Return

12. Arthur Drews (1865–1935), Professor of Philosophy at the Technical

University at Karlsruhe, spoke on 10 October 1920 in lectures organized by the free religious

congregation at Konstanz on 'Rudolf Steiner's Anthroposophy'. He repeated this lecture on 19

November in Mainz. His articles opposing Anthroposophy were published as a collection under the

title

Metaphysik and Anthropasophie in ihrer Stellung zur Erkenrunis des Obersinnlichen

(Metaphysics and Anthropasophy in their Position Regarding Knowledge of the Supersensible),

Berlin, 1922. Return

13. Eduard von Hartmann (1842–1906),

Philosophie des Unbewucsten: Versuch einer Weltanschauung

(Philosophy of the Unconscious: An Attempt at a World-View),

Berlin, 1869. Return

14. Count Hermann Keyserling (1880–1946). Compare, for example, the

chapter

'Für and wider die Theosophie'

('For and Against

Theosophy')

in

Philosophic als Kunst

(Philosophy as an Art),

Darmstadt, 1920. Return

|