These lectures deal with the inner connection between appearance and

reality in the world, and you have already seen that there are many

things of which those whose vision is limited to the world of

appearance have no idea. We have seen how every species of being

— this was shown by a number of examples — has its task in

the whole nexus of cosmic existence. Now today, as a kind of

recapitulation, we will again consider what I said recently about the

nature of several beings and in the first place of the butterfly. In

my description of this butterfly nature, as contrasted with that of

the plants, we found that the butterfly is essentially a being

belonging to the light — to the light in so far as it is modified by the

forces of the outer planets, of Mars, of Jupiter, and of Saturn. Hence,

if we wish to understand the butterfly in its true nature, we must in

fact look up into the higher regions of the cosmos, and must say to

ourselves: These higher cosmic regions endow and bless the earth, with

the world of the butterflies.

The bestowal of this blessing upon the earth has an even deeper

significance. Let us recall how we had to say that the butterfly does

not participate in what is directly connected with earthly existence,

but only indirectly, in so far as the sun, with its power of warmth

and light, is active in this earthly existence. Actually a butterfly

lays its eggs only where they do not become separated from sun

activity, so that the butterfly does not entrust its egg to the earth,

but only to the sun. Then out creeps the caterpillar, which is under

the influence of Mars-activity, though naturally the sun influence

always remains present. Then the chrysalis is formed, and

this is under the influence of Jupiter-activity. Out of the chrysalis

emerges the butterfly, which can now in its iridescent colours

reproduce in the earth's environment the luminous Sun-power of the

earth united with the power of Saturn.

Thus in the manifold colours of the butterfly world we see, in the

environment of earth-existence, the direct working of Saturn-activity

within the sphere of the earthly. But let us bear in mind that the

substances necessary for earth-existence are in fact of two kinds. We

have the purely material substances of the earth, and we have the

spiritual substances; and I told you that the remarkable thing about

this is that in the case of man the underlying substance of his

metabolic and limb system is spiritual whereas that of the head is

physical. Moreover in man's lower nature spiritual substance is

permeated with the activity of physical forces, with the action of

gravity, with the action of the other earthly forces. In the head, the

earthly substance, conjured up into it by the whole digestive process,

the circulation, nerve-activity and the like, is permeated by

super-sensible spiritual forces, which are reflected in our thinking,

in our power of forming mental pictures. Thus in the human head we

have spiritualized physical matter, and in the metabolic-limb-system

we have earthized — if I may coin a word — earthized

spiritual substantiality.

Now it is this spiritualized matter that we find to the greatest

degree in the butterfly. Because a butterfly always remains in the

sphere of sun-existence, it only takes to itself earthly matter —

naturally I am still speaking pictorially — as though in the form

of the finest dust. It also derives its nourishment from those earthly

substances which are worked upon by the sun. It unites with its own

being only what is sun-imbued; and it takes from earthly substance

only what is finest, and works on it until it is entirely

spiritualized. When we look at a butterfly's wing we actually have

before us earthly matter in its most spiritualized form. Through the

fact that the matter of the butterfly's wing is imbued with colour,

it is the most spiritualized of all earthly substances.

The butterfly is the creature which lives entirely in spiritualized

earth-matter. And one can even see spiritually how in a certain way a

butterfly despises the body which it carries between its coloured

wings, because its whole attention, its whole group-soul being, is

centred on its joyous delight in the colours of its wings.

And just as we marvel at its shimmering colours as we follow it, so

also can we marvel at its own fluttering joy in these colours. This is

something which it is of fundamental importance to cultivate in

children, this joy in the spirituality fluttering about in the air,

which is in fact fluttering joy, joy in the play of colours. The

nuances of butterfly-nature reflect all this in a wonderful way: and

something else lies in the background as well.

We were able to say of the bird — which we regarded as

represented by the eagle — that at its death it can carry

spiritualized earth-substance into the spiritual world, and that

thereby, as bird, it has the task in cosmic existence of

spiritualizing earthly matter, thus being able to accomplish what

cannot be done by man. The human being also possesses in his head

earth-matter which has been to a certain degree spiritualized, but he

cannot take this earthly matter into the world in which he lives

between death and a new birth, for he would continually have to endure

unspeakable, unbearable, devastating pain, if he were to carry this

spiritualized earth-matter of his head into the spiritual world.

The bird-world, represented by the eagle, can do this, so that thereby

a connection is actually created between what is earthly and what is

extra-earthly. Earthly matter is, as it were, gradually converted into

spirit, and the bird-creation has the task of giving over this

spiritualized earthly matter to the universe. One can actually say

that, when the earth has reached the end of its existence, this

earth-matter will have been spiritualized, and that the bird-creation

had its place in the whole economy of earthly existence for the

purpose of carrying back this spiritualized earth-matter into

spirit-land.

It is somewhat different with butterflies. The butterfly spiritualizes

earthly matter to an even greater degree than the bird. The bird after

all comes into much closer contact with the earth than does the

butterfly. I will explain this in detail later. Because the butterfly

never actually leaves the region of the sun, it is in a position to

spiritualize its matter to such a degree that it does not, like the

bird, have to await its death, but already during its life it is

continually restoring spiritualized matter to the environment of the

earth, to the cosmic environment of the earth.

Only think of the magnificence of all this in the whole cosmic

economy! Only picture the earth with the world of the butterflies

fluttering around it in its infinite variety, continually sending out

into world-space the spiritualized earthly matter which this

butterfly-world yields up to the cosmos! Then, with such knowledge, we

can contemplate the region of the world, of the butterflies encircling

the earth with totally different feelings.

We can look into this fluttering world and say: From you, O fluttering

creatures, there streams out something still better than sunlight; you

radiate spirit-light into the cosmos! Our materialistic science pays

but little heed to things of the spirit. And so this materialistic

science is absolutely unequipped with any means of grasping at these

things, which are, nevertheless, part of the whole cosmic economy.

They are there, just as the effects of physical activities are there,

and they are even more real. For what thus streams out into

spirit-land will work on further when the earth has long passed away,

whereas what is taught by the modern chemist and physicist will reach

its end with the conclusion of the earth's existence. So that if some

observer or other were to sit outside in the cosmos, with a long

period of time for observation, he would see something like a

continual outstreaming into spirit-land of matter which has become

spiritualized, as the earth radiates its own being out into cosmic

space; and he would see — like scintillating sparks, sparks which

ever and again flash up into light — what the bird-kingdom, what

every bird after its death sends forth as glittering light, streaming

out into the universe in the form of rays: a shimmering of the

spirit-light of the butterflies, and a sparkling of the spirit-light

of the birds.

Such things as these should also make us realize that, when we look up

to the rest of the starry world, we should not think that from there,

too, there only streams down what is shown by the spectroscope, or

rather what is conjured into the spectroscope by the fantasy of the

expert in optics. What streams down to earth from other worlds of the

stars is just as much the product of living beings in other worlds, as

what streams out from the earth into world-space is the product of

living beings. People look at a star, and with the modern physicist

picture it as something in the nature of a kindled inorganic flame

— or the like. This, of course, is absolute nonsense. For what we

behold there is entirely the product of something imbued with life,

imbued with soul, imbued with spirit.

And now let us pass inwards from this girdle of butterflies — if

I may call it so — which encircles the earth, and return to the

kingdom of the birds. If we call to mind something which is already

known to us, we must picture three regions adjoining each other. There

are other regions above these, and again other regions below them. We

have the light-ether and we have the warmth-ether, which, however,

actually consists of two parts, of two layers, the one being the layer

of earthly warmth, the other that of cosmic warmth, and these

continually play one into the other. Thus we have not only one, but

two kinds of warmth, the one which is of earthly, tellurian origin, and

the other of a kind which is of cosmic origin. These are always

playing one into the other. Then, bordering on the warmth-ether, there

is the air. Below this would come water and earth, and above would

come chemical ether and light-ether.

The world of the butterflies belongs more particularly to the

light-ether; it is the light-ether itself which is the means whereby

the power of the light draws forth the caterpillar from the

butterfly's egg. Essentially it is the power of the light which draws

the caterpillar forth.

This is not the case with the bird-kingdom. The birds lay their eggs.

These must now be hatched out by warmth. The butterfly's egg is simply

given over to what is of the nature of the sun; the bird's egg comes

into the region of warmth. It is in the region of the warmth-ether

that the bird has its being, and it overcomes what is purely of the

air.

The butterfly, too, flies in the air, but fundamentally it is

entirely a creature of the light. And in that the air is permeated

with light, in this light-air existence, the butterfly chooses not air

existence but light existence. For the butterfly the air is only what

sustains it — the waves, as it were, upon which it floats; but

the butterfly's element is the light. The bird flies in the air, but

its element is the warmth, the various differentiations of warmth in

the air, and to a certain degree it overcomes the air. Certainly the

bird is also an air-being inwardly and to a high degree. The bones of

the mammals, the bones of the human being are filled with marrow. (We

shall speak later as to why this is the case.) The bones of a bird are

hollow and are filled only with air. We consist, in so far as the

content of our bones is concerned, of what is of the nature of marrow;

a bird consists of air. And what is of the nature of marrow in us for

the bird is simply air. If you take the lungs of a bird, you will find

a whole quantity of pockets which project from the lungs; these are

air-pockets. When the bird inhales it does not only breathe air into

its lungs, but it breathes the air into these air-pockets, and from

thence it passes into the hollow bones. So that, if one could remove from

the bird all its flesh and all its feathers and also take away the

bones, one would still get a creature composed of air, having the form

of what inwardly fills out the lungs, and what inwardly fills out all

the bones. Picturing this in accordance with its form, you would

really get the form of the bird. Within the eagle of flesh and bone

dwells an eagle of air. This is not only because within the eagle

there is also an eagle of air. The bird breathes and through its

breathing it produces warmth. This warmth the bird imparts to the air,

and draws it into its entire limb system. Thus arises the difference

of temperature as compared to its outer environment. The bird has its

inner warmth, as against the outer warmth. In this difference of

degree between the warmth of the outer air and the warmth which the

bird imparts to its own air within itself — it is really in this

that the bird lives and has its being. And if you were to ask a bird

how matters are with its body — supposing you understood bird

language — the bird's reply would make you realize that it

regards its solid material bones, and other material adjuncts, rather

as you would luggage if you were loaded, left and right, on the back

and on the head. You would not call this luggage your body. In the

same way the bird, in speaking of itself, would only speak of the

warmth-imbued air, and of everything else as the luggage which it

bears about with it in earthly existence. These bones, which envelop

the real body of the bird, these are its luggage. We are therefore,

speaking in an absolute sense when we say that fundamentally the bird

lives only and entirely in the element of warmth, and the butterfly

in the element of light. For the butterfly everything of the nature of

physical substance, which it spiritualizes, is, before this

spiritualizing, not even personal luggage but more like furniture. It

is even more remote from its real being.

When we thus ascend to the creatures of these regions, we come to

something which cannot be judged in a physical way. If we do so, it is

rather as if we were to draw a person with his hair growing out of the

bundle on his head, boxes growing together with his arms, and a

rucksack growing out of his back, making him appear a perfect

hunch-back. If one were to draw a person in this way, it would

actually correspond to the materialist's view of the bird. That is not

the bird; it is the bird's luggage. The bird really feels encumbered

by having to drag his luggage about, for it would like best to pursue

its way through the world, free and unencumbered, as a creature of

warm air. For the bird all else is a burden. And the bird pays tribute

to world-existence by spiritualizing this burden for it, sending it

out when it dies into spirit-land; a tribute which the butterfly

already pays during its lifetime.

You see, the bird breathes, and makes use of the air in the way I told

you. It is otherwise with the butterfly. The butterfly does not in any

way breathe by means of an apparatus such as the so-called higher

animals possess — though these in fact are only the more bulky,

not in reality the higher animals. The butterfly breathes in fact only

through tubes which proceed inwards from its outer casing, and, these

being somewhat dilated, it can accumulate air during flight, so that

it is not inconvenienced by always needing to breathe.

The butterfly always breathes through tubes which pass into its

interior. Because this is so, it can take up into its whole body,

together with the air which it inhales, the light which is in the air.

Here, too, a great difference is to be found.

Let us represent this in a diagram. Picture to yourselves one of the

higher animals, one with lungs. Into the lungs comes oxygen, and there

it unites with the blood in its course through the heart. In the case

of these bulky animals, and also with man, the blood must flow into

the heart and lungs in order to come into contact with oxygen.

In the case of the butterfly I must draw the diagram quite

differently. Here I must draw it in this way: If this is the

butterfly, the tubes everywhere pass inwards; they then branch out

more widely. And now the oxygen enters in everywhere, and spreads

itself out through the tubes; so that the air penetrates into the

whole body.

With us, and with the so-called higher animals, the air comes as far

as the lungs as air only; in the case of the butterfly the

outer air, with its content of light, is dispersed into the

whole interior of the body. The bird diffuses the air right into its

hollow bones; the butterfly is not only a creature of light outwardly,

but it diffuses the light which is carried by the air into every part

of its entire body, so that inwardly too the butterfly is composed of

light. Just as I could characterize the bird as warmed air, so in fact

is the butterfly composed entirely of light. Its body also consists of

light; and for the butterfly warmth is actually a burden, is luggage.

It flutters about only and entirely in the light, and it is light only

that it builds into its body. When we see the butterflies fluttering

in the air, what we must really see is only fluttering beings of

light, beings of light rejoicing in their play of colours. All else is

garment, is luggage. We must gain an understanding of what the beings

around earth really consist, for outward appearance is deceptive.

Those who today have learned, in some superficial manner, this or that

out of oriental wisdom speak about the world as Maya. But to say that

the world is Maya really implies nothing. One must have insight into

the details of why it is Maya. We understand Maya when we know that

the real nature of the bird in no way accords with what is to be seen

outwardly, but that it is a being of warm air. The butterfly is not at

all what it appears to be, but what is seen fluttering about is a

being of light, a being which actually consists of joy in the play of

colours, in that play of colours which arises on the butterfly's wings

through the earthly dust-substance being imbued with the element of

colour, and thus entering on the first stage of its spiritualisation

on the way out into the spiritual universe, into the spiritual cosmos.

You see, we have here, as it were, two levels: the butterfly, the

inhabitant of the light-ether in an earth environment, and the bird,

the inhabitant of the warmth-ether. And now comes the third level.

When we descend into the air, we arrive at those beings which, at a

certain period of our earth-evolution, could not yet have been there

at all; for instance at the time when the moon had not yet separated

from the earth but was still with it. Here we come to beings which are

certainly also air-beings, living in the air, but which are in fact

already strongly influenced by what is peculiar to the earth, gravity.

The butterfly is completely untouched by earth-gravity. It flutters

joyfully in the light-ether, and feels itself to be a creation of that

ether. The bird overcomes gravity by imbuing the air within it with

warmth, thereby becoming a being of warm air — and warm air is

upborne by cold air. Earth-gravity is also overcome by the bird.

Those creatures which by reason of their origin must still live in the

air but which are unable to overcome earth-gravity, because they have

not hollow bones but bones filled with marrow, and also because they

have not air-sacs like the birds — these creatures are the bats.

The bats are a quite remarkable order of animal-life. In no way do

they overcome the gravity of earth through what is inside their

bodies. They do not, like the butterflies, possess the lightness of light, or,

like the bird, the lightness of warmth; they are subject to

earth-gravity, and they experience themselves in their flesh and bone.

Hence that element of which the butterfly consists, which is its whole

sphere of life — the element of light — this is disagreeable

to bats. They like the dusk. Bats have to make use of the air, but

they like the air best when it is not the bearer of light. They yield

themselves up to the dusk. They are veritable creatures of the dusk.

And bats can only maintain themselves in the air because they possess

their somewhat caricature-like bat-wings, which are not wings at all

in the true sense, but stretched membrane, membrane stretched between

their elongated fingers, a kind of parachute. By means of these they

maintain themselves in the air. They overcome gravity — as a

counter-weight — by opposing it with something which itself is

related to gravity. Through this, however, they are completely yoked

into the domain of earth-forces. One could never construct the flight

of a butterfly solely according to physical, mechanical laws, neither

could one the flight of a bird. Things would never come out absolutely

right. In their case we must introduce something containing other laws

of construction. But the bat's flight, that you can certainly

construct according to earthly dynamics and mechanics.

The bat does not like the light, the light-imbued air, but at the most

only twilight air. And the bat also differs from the bird through the

fact that the bird, when it looks about it, always has in view what is

in the air. Even the vulture, when it steals a lamb, perceives it as

it sees it from above, as though it were at the end of the light

sphere, like something painted onto the earth. And quite apart from

this, it is no mere act of seeing; it is a craving. What you would

perceive if you actually saw the flight of the vulture towards the

lamb is a veritable dynamic of intention, of volition, of craving.

A butterfly sees what is on the earth as though in a mirror; for the

butterfly the earth is a mirror. It sees what is in the cosmos. When

you see a butterfly fluttering about, you must picture to yourselves

that it disregards the earth, that for it the earth is just a mirror

for what is in the cosmos. A bird does not see what belongs to the

earth, but it sees what is in the air. The bat only perceives what it

flies through, or flies past. And because it does not like the light,

it is unpleasantly affected by everything it sees. It can certainly be

said that the butterfly and the bird see in a very spiritual way. The

first creature — descending from above downwards — which

must see in an earthly way, is disagreeably affected by this seeing. A

bat dislikes seeing, and in consequence it has a kind of embodied fear

of what it sees, but does not want to see. And so it would like to

slip past everything. It is obliged to see, yet is unwilling to do so

— and thus it everywhere tries just to skirt past. And it is

because it desires just to slip past everything, that it is so

wonderfully intent on listening. The bat is actually a creature which

is continually listening to its own flight, lest this flight should be

in any way endangered.

Only look at the bat's ears. You can see from them that they are

attuned to world-fear. So they are — these bats' ears. They are

quite remarkable structures, attuned to evading the world, to

world-fear. All this, you see, is only to be understood when the bat

is studied in the framework into which we have just placed it.

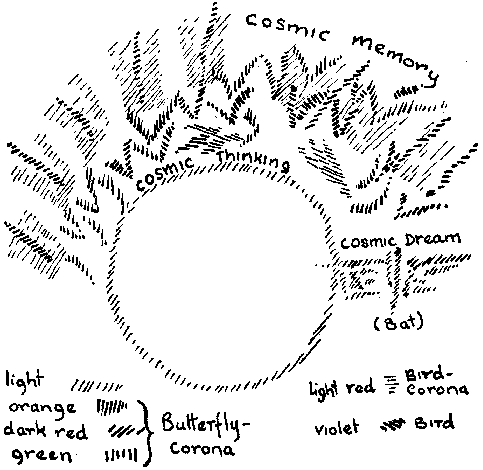

Here we must add something further. The butterfly continually imparts

spiritualized matter to the cosmos. It is the darling of the Saturn

influences. Now call to mind how I described Saturn as the great

bearer of the memory of our planetary system. The butterfly is closely

connected with what makes provision for memory in our planet. It is

memory-thoughts which live in the butterfly. The bird — this,

too, I have already described — is entirely a head, and as it

flies through the warmth-imbued air in world-space it is actually the

living, flying thought. What we have within us as thoughts — and

this also is connected with the warmth-ether — is bird-nature,

eagle-nature, in us. The bird is the flying thought. But the bat is

the flying dream; the flying dream-picture of the cosmos. So we can

say: The earth is surrounded by a web of butterflies — this is

cosmic memory; and by the kingdom of the birds — this is cosmic

thinking; and by the bats — they are the cosmic dream, cosmic

dreaming. It is actually the flying dreams of the cosmos which sough

through space as the bats. And as dreams love the twilight, so, too,

does the cosmos love the twilight when it sends the bat through space.

The enduring thoughts of memory, these we see embodied in the girdle

of butterflies encircling the earth; thoughts of the moment we see in

the bird-girdle of the earth; and dreams in the environment of the

earth fly about embodied as bats. And you will surely feel, if we

penetrate deeply into their form, how much affinity there is between

this appearance of the bat and dreaming! One simply cannot look at a

bat without the thought arising: I must be dreaming; that is really

something which should not be there, something which is as much

outside the other creations of nature as dreams are outside ordinary

physical reality.

To sum up we can say: The butterfly sends spiritualized substance into

spirit-land during its lifetime; the bird sends it out after its

death. Now what does the bat do? During its lifetime the bat gives off

spiritualized substance, especially that spiritualized substance which

exists in the stretched membrane between its separate fingers. But it

does not give this over to the cosmos; it sheds it into the atmosphere

of the earth. Thereby beads of spirit, so to say, are continually

arising in the atmosphere.

Thus we find the earth to be surrounded by the continual glimmer of

out-streaming spirit-matter from the butterflies and sparkling into

this what comes from the dying birds; but also, streaming back towards

the earth, we find peculiar segregations of air where the bats give

off what they spiritualize. Those are the spiritual formations which

are always to be observed when one sees a bat in flight. In fact a bat

always has a kind of tail behind it, like a comet. The bat gives off

spirit-matter; but instead of sending it outwards, it thrusts it back

into the physical substance of the earth. It thrusts it back into the

air. And just as one sees with the physical eye physical bats

fluttering about, one can also see these corresponding

spirit-formations which emanate from the bats fluttering through the

air; they sough through the spaces of the air. We know that air

consists of oxygen, nitrogen and other constituents, but this is not

all; it also consists of the spirit-emanations of bats.

Strange and paradoxical as it may sound, this dream-order of the bats

sends little spectres out into the air, which then unite into a

general mass. In geology the matter below the earth, which is a

rock-mass of a soft consistency like porridge, is called magma. We

might also speak of a spirit-magma in the air, which comes from the

emanations of bats.

In ancient times when an instinctive clairvoyance prevailed, people

were very susceptible to this spirit magma, just as today many people

are very susceptible to what is of a material nature, for instance,

bad smelling air. This might certainly be regarded as somewhat vulgar,

whereas in the ancient instinctive time of clairvoyance people were

susceptible to the bat-residue which is present in the air.

They protected themselves against this. And in many Mysteries there

were special formulas whereby people could inwardly arm themselves, so

that this bat-residue might have no power over them. For as human

beings we do not only inhale oxygen and nitrogen with the air, we also

inhale these emanations of the bats. Modern people, however, are not

interested in letting themselves be protected against these

bat-remains, but whereas in certain conditions they are highly

sensitive, let us say, to bad smells, they are highly insensitive to

the emanations of the bats. It can really be said that they swallow

them down without feeling the least trace of repulsion. It is quite

extraordinary that people who are otherwise really prudish just

swallow down what contains the stuff of which I have spoken.

Nevertheless this too enters into the human being. Certainly it does

not enter into the physical or etheric body, but it enters into the

astral body.

Yes, you see, we here find remarkable connections. Initiation science

everywhere leads into the inner aspect of relationships; this

bat-residue is the most craved-for nutriment of what I have described

in lectures here as the Dragon. But this bat-residue must first be

breathed into the human being. The Dragon finds his surest foothold in

human nature when man allows his instincts to be imbued with these

emanations of the bats. There they seethe. And the dragon feeds on

them and grows — in a spiritual sense, of course — gaining

power over people, gaining power in the most manifold ways. This is

something against which modern man must again protect himself: and the

protection should come from what has been described here as the new

form of Michael's fight with the Dragon. The increase in inner

strength which man gains when he takes up into himself the Michael

impulse as it has been described here, this is his safeguard against

the nutriment which the Dragon desires; this is his protection against

the unjustified bat-emanations in the atmosphere.

If one has the will to penetrate into these inner world-connections,

one must not shrink back from facing the truths contained in them. For

today the generally accepted form of the search for truth does not in

any way lead to actuality, but at most to something even less actual

than a dream, to Maya. Reality must of necessity be sought in the

domain where all physical existence is regarded as interwoven with

spiritual existence. We can only find our way to reality, when this

reality is studied and observed, as has been done here in the present

lectures.

In everything good and in everything evil, in some way or other beings

are present. Everything in world-connections is so ordered that its

relation to other beings can be recognized. For the materialistically

minded, butterflies flutter, birds fly, bats flit. But this can really

be compared to what often happens with a not very artistic person, who

adorns the walls of his room with all manner of pictures which do not

belong to each other, which have no inner connection. Thus for the

ordinary observer of nature, what flies through the world also has no

inner connection; because he sees none. But everything in the cosmos

has its own place, because just from this very place it has a relation

to the cosmos in its totality. Be it butterfly, bird, or bat,

everything has its own meaning within the world-order.

As to those who today wish to scoff, let them scoff. People already

have other things to their credit in the sphere of ridicule.

Celebrated scholars have declared that meteor-stones cannot exist,

because iron cannot fall from heaven, and so on. Why then should

people not also scoff at the functions of the bats, about which I have

spoken today? Such things, however, should not divert us from the task

of imbuing our civilization with a knowledge of spiritual truths.

|