Lecture VIII

Dornach,

January 17, 1917

The pictures we shall show

today will enable us to give a kind of recapitulation of various things

that came before our souls in former lectures. I shall draw attention

today to further aspects, arising out of what we have said before. In

the course of these studies, we have distinguished between the more

Southern European and the Northern or Mid-European artistic streams

and we have indicated characteristic aspects of these two. I do not

wish to repeat what has already been set forth. Today we are able to

show some further reproductions of pictures by Raphael, and I wish to

say a few words about him, unfolding — if I may so describe it

— a more special outcome of our ideas concerning the artistic

genius of the South.

Anyone who lets Raphael's

creations work upon his soul, will admit that in Raphael — with

respect to certain artistic intentions — the highest ideal has

been attained. When we let them work upon us and try to understand them,

we ask ourselves again and again: What is it that comes to expression

in his works, and how does it stand in relation to the World? Think

for a moment from this aspect of the Madonna della Sedia, — how

this picture is placed in a great world-perspective: It is so, indeed,

in all directions. To begin with, you may consider the picture as an

outcome of the Christian world-conception. So perfectly does it express

this theme: The Birth of Christ Jesus in connection with the Madonna,

that we must say, 'The ides, the meaning, the impulse, the world-historic

significance which it is desired to express, has here been expressed

by means that cannot ever be transcended.

From a certain point of

view you cannot imagine a further enhancement of this theme —

the Madonna with the Jesus Child — in its impression on the human

soul. One of the ideas of the Christian conception of the world has

come to expression here in the highest imaginable way, seen from a certain

aspect.

1. Raphael. Madonna With Child.

And now let us look at the

picture for a moment as though we knew nothing of the Christian

world-conception. Let us consider it in the way Herman Grimm once spoke

of it, simply as an expression of the deep mystery of the relation of the

mother to the child. A mother with her child: Once more, the highest means

of expression have been found by Raphael for one of the most mysterious

themes in the whole Cosmos, as it lies before us human beings living

in the Physical. Thus even if we take the pure picture of Nature —

the mother and child — apart from the world-historic happenings,

once more the thing is perfect in itself, the highest of its kind.

It is always so with Raphael.

His themes are of universal significance, and perfectly expressed, —

the means of expression proceeding from those streams and influences

which we recognise as characteristic of the South. Always, however,

his themes must be seen in the context of great universal meanings.

We can regard them from a Christian aspect (and the above two points of

view are by no means the only ones), — looking at it in a Christian

way, the theme places itself at once in a great context of Nature. Again

it rises free from the individually human; we seem to forget the human

being that worked to create it — the human being, Raphael himself.

Behind the artist stand great cosmic perspectives — world-conceptions

coming to expression in him. This, indeed, is to characterise such an

artist as Raphael, as the artist of an epoch that was drawing to it

close: the Fourth Post Atlantean epoch. Such epochs, when they draw

near their end — or when their inner essence reaches beyond the

boundary of times, often bring forth their very highest.

We shall presently see how

very different it is when we consider in this light, say, the personality

of Albrecht Dürer. There it is altogether different. But you might

also think of the Sistine Madonna, even as we have now spoken of the

Madonna della Sedia. Again we should have to say: What is here placed

before us interests us, above all, inasmuch as it stands out against

the background of a great world-conception. Without this background of a

great world-conception, the Sistine Madonna is, indeed, unthinkable.

2. Raphael. Sistine Madonna With Child

3. Raphael. Sistine Madonna With Child (detail)

Looking at some of Raphael's

pictures today, let us bear in mind the aspect which has thus been

characterised. For Raphael to create in this way — for his pictures

to arise out of a mighty world-perspective — something of cosmic law

and principle had to be working in his very soul. This is, indeed, the

case. It comes to expression in the remarkable course of his life, which

was already emphasized by Hermann Grimm. Raphael's work takes its course

in regular cyclic periods. At the age of twenty-one he creates the

Sposalize; four years later the Entombment; four years after

this he completes the Frescoes of the Camera della Segnatura; four

years later, once again, the Cartoons for the tapestries in the

Vatican and the two Madonnas. And finally, four years after this, at the

age of thirty-seven, he is working at the Transfiguration, which

stands unfinished when he leaves this physical plane. In cyclic periods

of four years, something of the nature of a cosmic principle works in

Raphael. Truly, we here have something that proceeds from a great cosmic

background. Hence Raphael's work is so strongly separated from his

personality. Again and again the question comes to us: How is it that

the themes — and they are world-historic themes — come to

expression in his work so perfectly; so self-contained, so inwardly

complete?

Down to this day, the study

of Art derives — more than from any other source — from

that great Art in the center of which is Raphael.

The study of Art in the

exoteric life today is more or less of this kind. All its available

ideas have been learned from the Art which finds its highest expression

in Raphael — the Art of the Italian Renaissance. Thus in the outer

life the concepts to express this Art are the most perfect, and all

other Art is measured by this standard. The works of this Art are the

ideal, and we have few words at our disposal, few concepts and ideas,

even to speak of any other streams in Art, specifically different from

this one. That is the unique thing.

And now we will let pass

before our souls a number of pictures by Raphael, most of which we have

not yet seen in these lectures.

4. Raphael. The Vision of Ezekiel. (Florence,

Palazzo Pitti.)

4. Raphael. The Vision of Ezekiel. (detail)

(Pitti. Florence.)

The ideas, the living

conceptions, out of which such a picture proceeded even in Raphael's time,

are naturally no longer near us today. To represent so truly this wandering

of the soul in human form through the spiritual world, would no longer be

attainable today for those who have not Spiritual Science. The animal

nature below expressed what man has cast aside from himself, but it is

still there, needless to say, even in his etheric body, and we find it

there when the etheric is freed from the physical. The union of the soul

with something childlike, as it is is represented by the angel figures

here, is an absolutely true conception. The conception corresponds to a

reality. We must consider man in his full being, such as he really is. In

recent communications on the Guardian of the Threshold we had to speak of

the Threefold being of Man. This threefold nature of man emerges

everywhere, where reference is made to the Spiritual part of man

emancipated from the Physical. We find this threefoldness in manifold

forms — not symbolic, but corresponding to spiritual Realities. And

so we find it here, in the full-grown Man related to the Child and the

Beast.

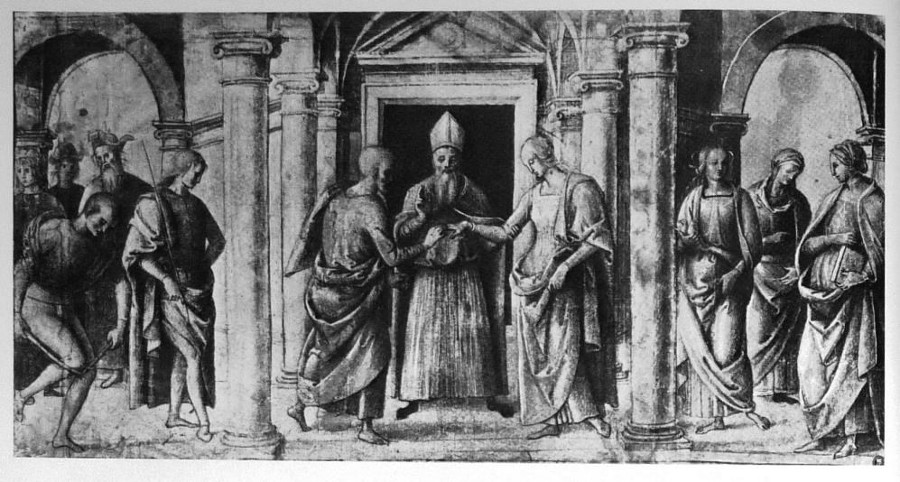

5. Perugino. The Marriage of Maria. (Vienna,

Albertina.)

Today we are able to show

a study from the Sposalizo, the picture with which Raphael's great career

as an artist properly begins. He did this at the age of twenty-one —

at the beginning of the four-year period which dominated all his work.

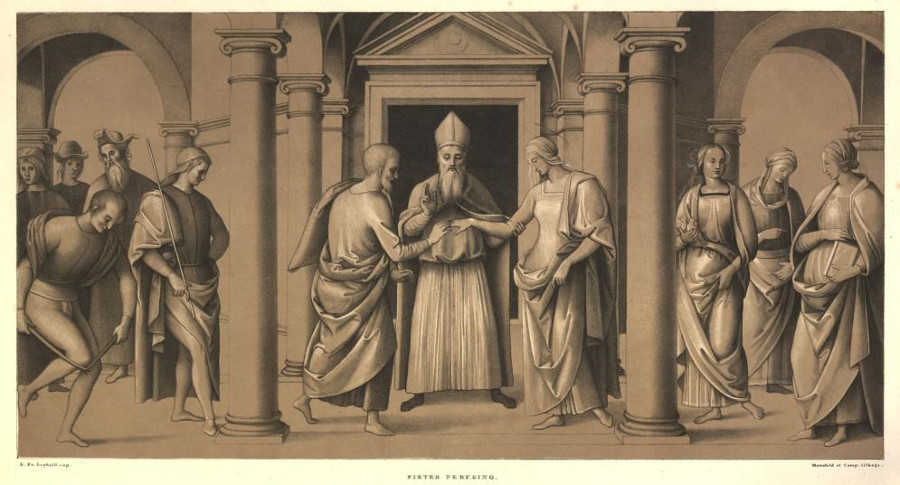

6. Perugino. “Sposalizo”. (Caen.)

7. Raphael. “Sposalizo”. (Milan,

Brera.)

8. Raphael. The Call of St. Peter. (London,

Kensington Museum.)

9. Raphael. The Road to Calvary. (Madrid, Prado.)

10. Raphael. Sketch of the Mourning for Christ.

(Louvre. Paris.)

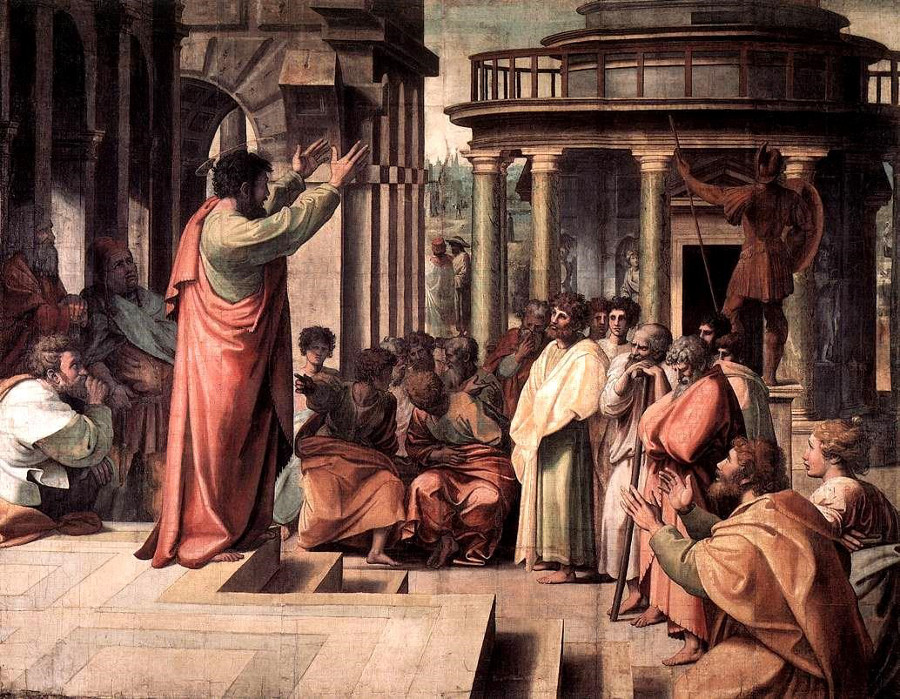

11. Raphael. Sermon of St. Paul at Athens.

(London, Kensington Museum.)

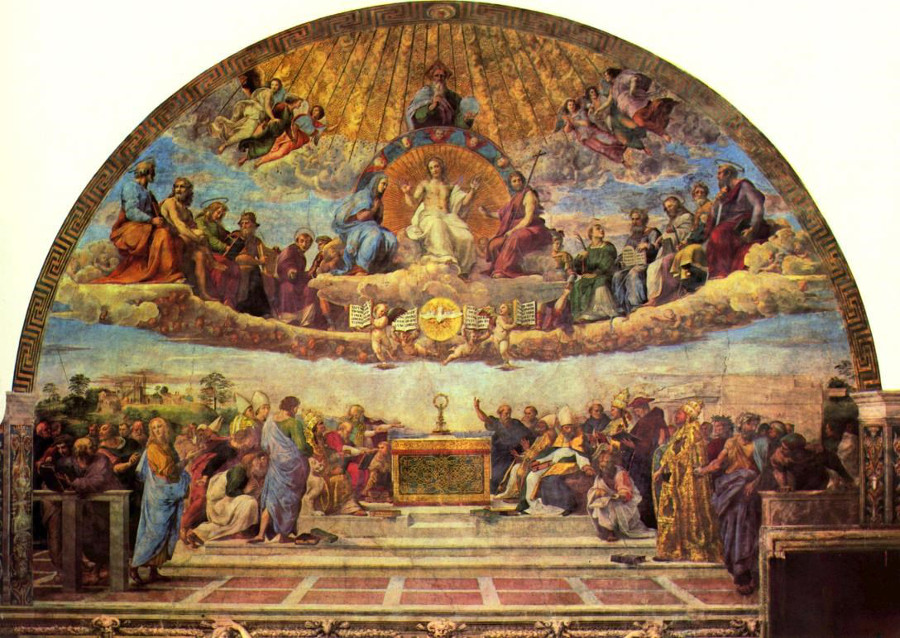

We will now show once

more a reproduction of the so-called “Disputa,” with certain

details.

12. Raphael. Disputa. (Vatican. Rome.)

13. Raphael. The Holy Trinity. (Perugia, San

Severo.)

The Holy Trinity, as it

is called.

14. Raphael. Sketch for the Disputa. (Windsor.)

15. Raphael. St. Cecilia. (Bologna.)

And now, as an example

of Raphael's portraiture: —

16. Raphael. Cardinal Bihbiens. (Pitti. Florence.)

The next two are examples

of his tapestries in the Vatican.

17. Raphael. The Miraculous Draught of Fishes.

(Tapestry in the Vatican.)

18. Raphael. The Healing of the Lame. (Tapestry

in the Vatican.)

These are the things of

which Goethe said that nothing he had known till then could compare

with them in greatness.

Looking back once more over

the pictures by Raphael which we have seen today, I beg you observe how we

may recognise in them the echoing of a mighty tradition of great Art.

Even the sketches which we have shown today reveal this most especially.

Raphael's work is the last, the highest, the closing act in a great

tradition. There is also another point I would ask you to consider.

Think of the picture of the Sermon of St. Paul and others — the

“Disputa,” for example. You may take any one of those that

we have seen today. In every case, having distinguished the subject of

the picture, you may naturally ask yourself about the event or personality

represented. But it will never be sufficient to answer: The subject

is such and such; it represents this or that. In Raphael's case you

will have to ask: How is the artist contriving to express — whatever

the subject is — in accordance with the ideas and canons of great

Art? We cannot merely ask: How would St. Paul actually have lifted up

his hand to speak? With Raphael we must ask: What angle will the arm

have to make with the body according to aesthetic laws of balance and

proportion? And so forth ... A magic breath is poured out over it

all, — a magic breath of aesthetic traditions, of harmony and

balance. Look at the boy who stands here, in this picture. It is not

enough to ask: What is going on in the soul of the boy? Your question

must, rather, be directed to these laws of artistic harmony. See how

the line of the arm, reaching out on either side, is placed into the

composition. In short, you can distinguish what is purely artistic from

the underlying subject-matter. Here, however, the artist's power is

so magnificent that it draws the subject-matter into its own sphere.

With such an artist as Raphael, we may, indeed, pronounce the word,

for it is literally true: — “Artistic truth makes all the

rest true, — compels all the rest into its circle.”

You cannot apply this saying,

in its present meaning, to the works we shall now let pass before our

souls. We will begin with one by Martin Schongauer, who died in 1488.

19. Martin Schongauer. The Road to Calvary.

Here you see the very

opposite. To begin with, the artist is simply concerned to express his

subject. No longer is there poured out over it the magic breath of a

peculiarly aesthetic truth, the climax of a great tradition. Here the

effort is, to the best of the artist's technique and ability, with the

artistic means at his disposal, to bring to expression what is there in

the souls of men. Here the world speaks to us directly — not

through the medium of a tradition of great Art.

We will now let work upon

our souls the personality of Albrecht Dürer; showing a number of

pictures which we did not see in the former lectures. In Albrecht Dürer,

whom we may speak of as a contemporary of Raphael, we have before us an

altogether different personality. It is impossible to think of Dürer's

works in the same way as of Raphael's. In Dürer's case we shall

not easily forget the personality, the human being. Not that we must

always necessarily imagine him; but the pictures themselves are eloquent

of all that is direct and intimate and near to the human soul, springing

from the soul with elemental force. Raphael paints with the ever-present

background of great world-perspectives. He is only conceivable if we

imagine, as it were, the Genius of Christianity itself painting in the

soul of Raphael. And, again, he is only conceivable as one who stands

at the close of a great epoch, during which pupils were learning from

their Masters many a tradition of aesthetic law, artistic harmony, —

learning that certain things should be done in certain ways, to correspond

with the canons of great Art.

In Raphael's works these

things are always there before us. In Dürer's work, on the other

hand, we feel in the background, as it were, the aura of the life of

the time in Middle Europe, — the German towns and cities. Invisibly

his pictures are pervaded by all that blossomed forth in the free life

of the cities, working its way towards the Reformation. Nor does he

stand before us with any cosmic perspectives in the background. It is,

rather, the ordinary individual man's approach to the Bible and to his

fellow-men, bringing his own soul to expression. The Human element can

never be separated from his works. We cannot seek in Dürer for

a cosmic principle working through his soul, as we can in Raphael. But

we may look for something intimate and deep; deeply connected —

we cannot say so too often — with the human soul, its feelings

and its seeking, its longing and striving.

20. Dürer. The Four Witches. (Etching)

21. Dürer. Hercules.

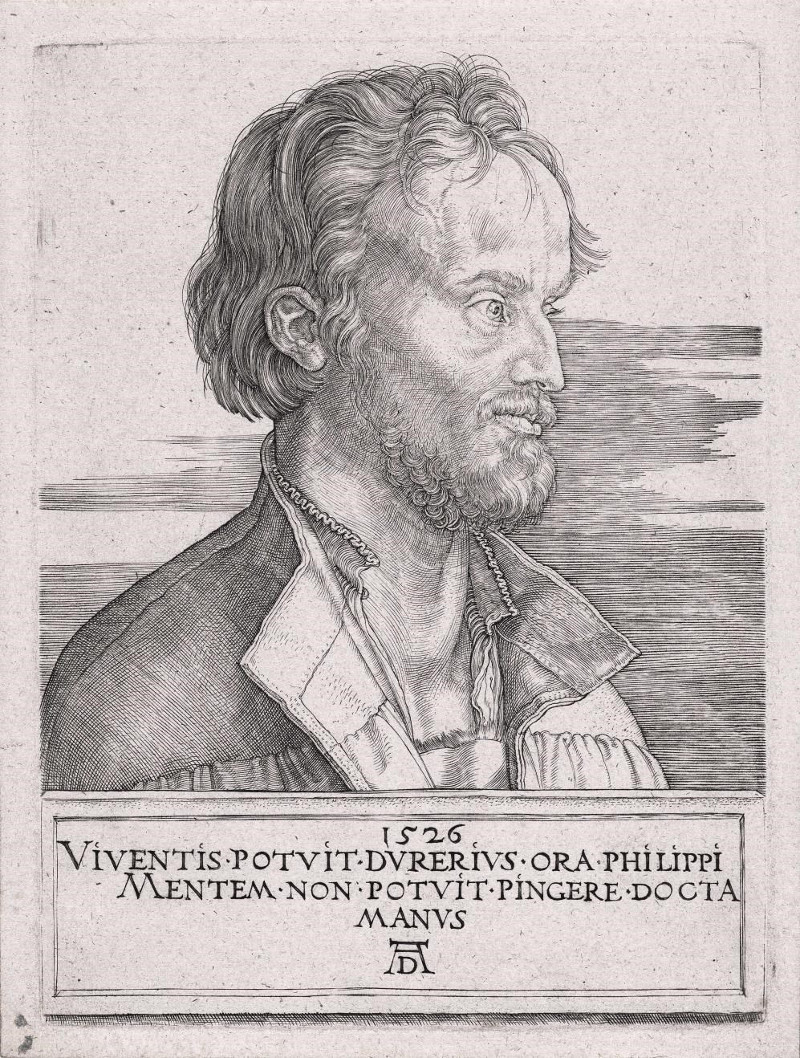

22. Dürer. Melanchthon Etching.

Here we have a portrait

of Melanchthon, the theological bearer of the Reformation, as against

Luther, who was the “priestly” bearer.

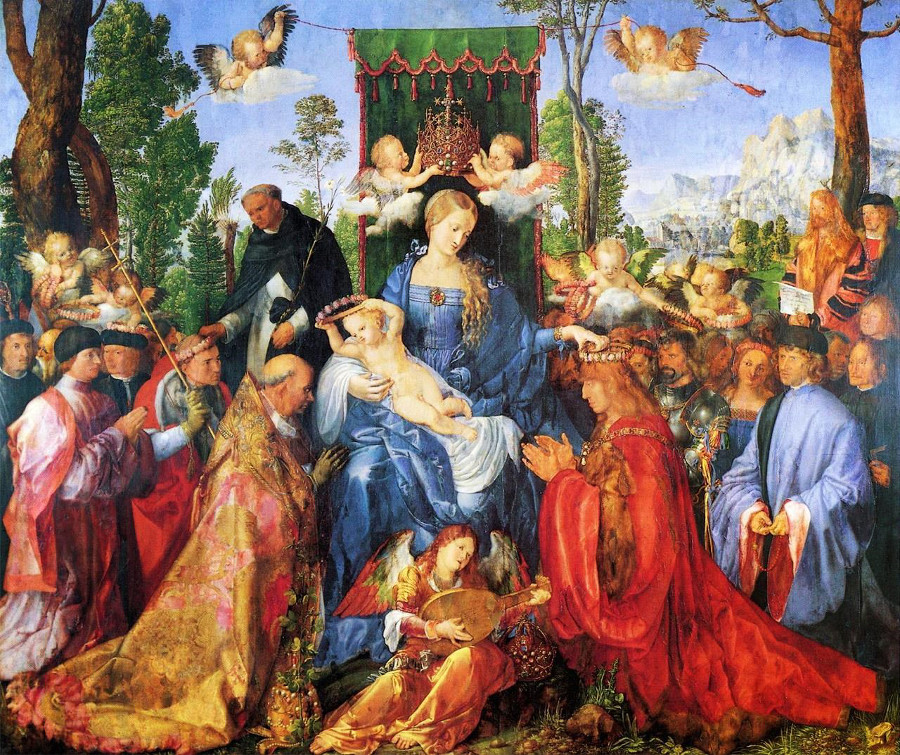

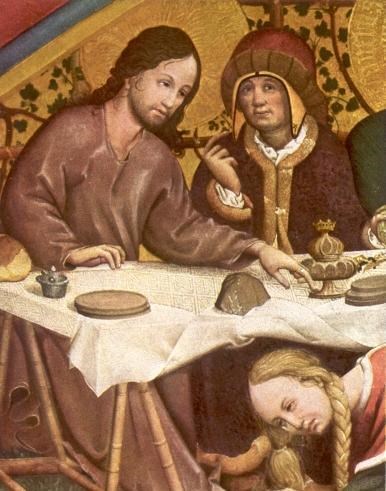

23. Dürer. “Rosenkranzfest.”

(Prague.)

This picture is now in the

“Rudolfinum” at Prague. The Pope, the Emperor and

representatives of Christianity are being crowned with roses by Mary,

the Jesus Child and St. Dominic. The two figures against the tree trunk

will be shown in detail in the next slide.

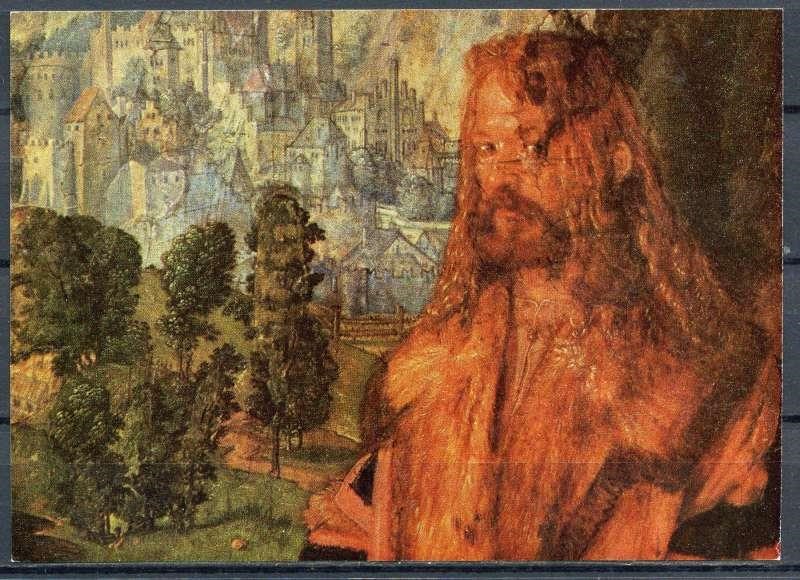

24. Dürer. Portrait of Himself and Pirkheimer.

(Detail of the above.)

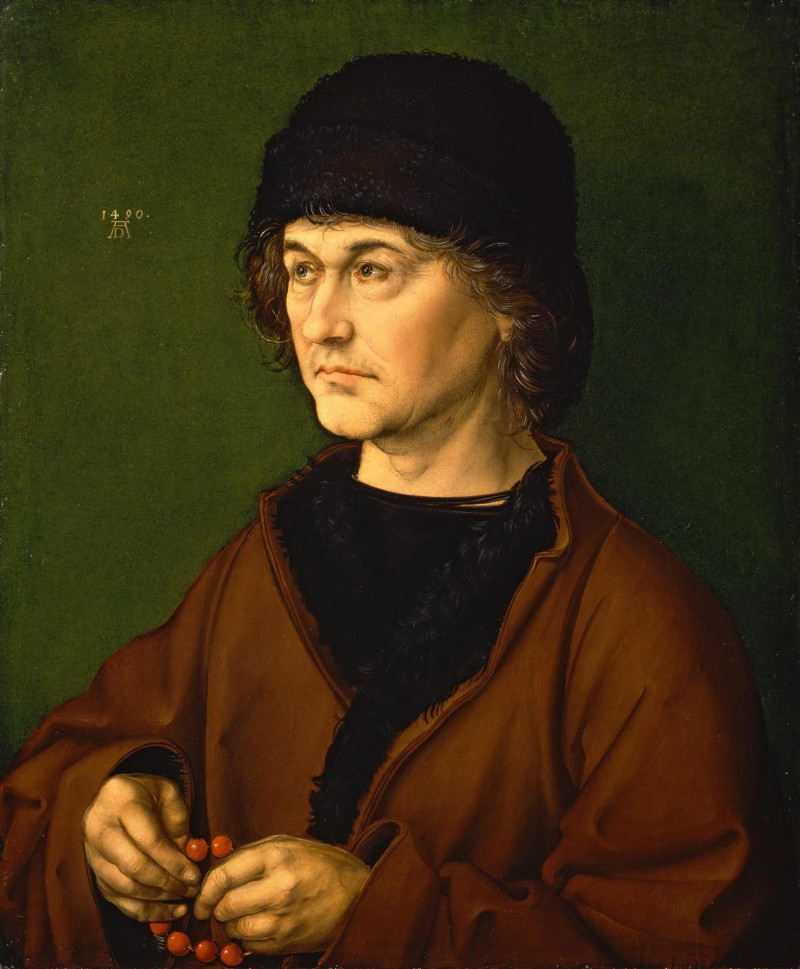

Further examples of Dürer's portraiture: —

25. Dürer. Portrait of his Father. (Uffizi.

Florence.)

26. Dürer. Portrait. (Prado. Madrid.)

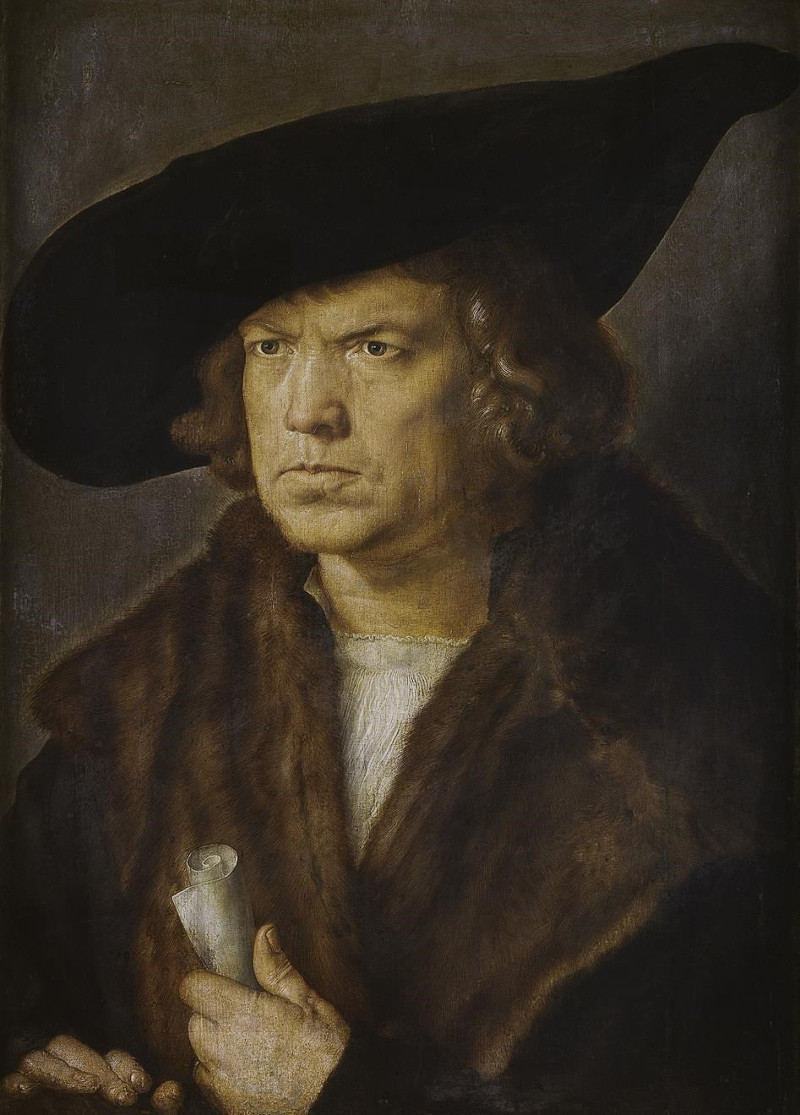

Looking at such a portrait,

the whole life of the time comes vividly before you. Truly, in this

sense Dürer is an historic figure of the very first rank. No historic

document tells us so well, what the people of that time were like.

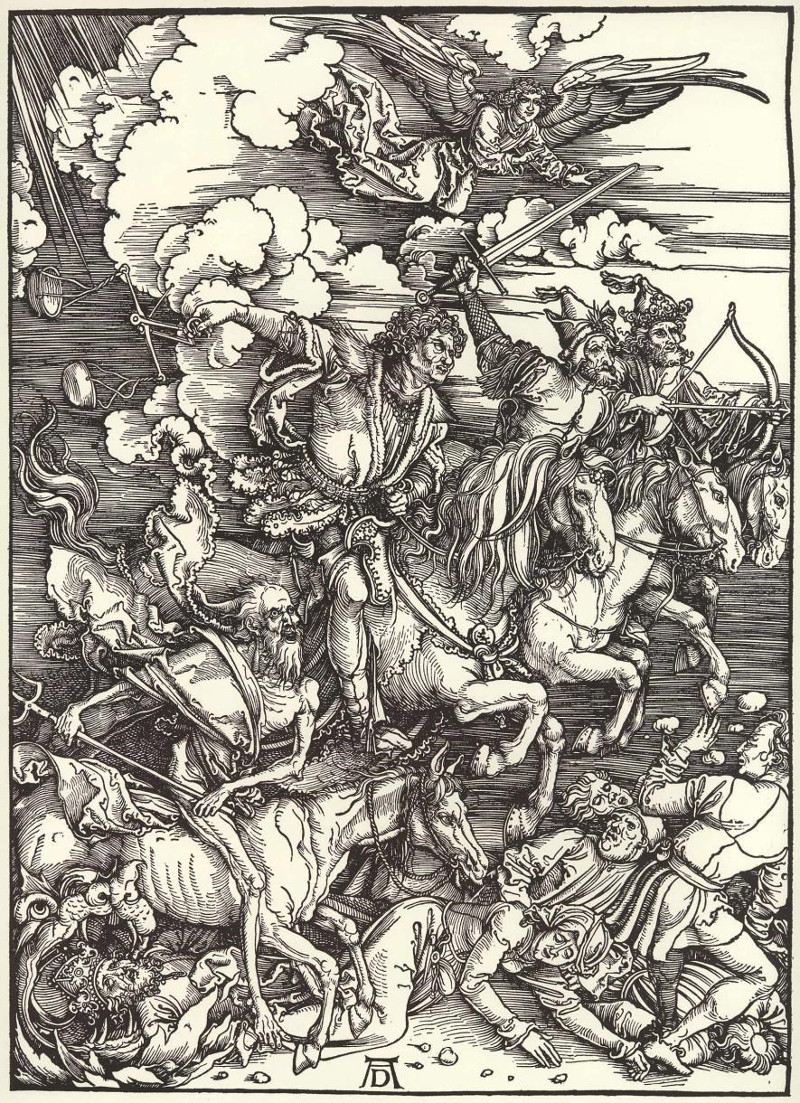

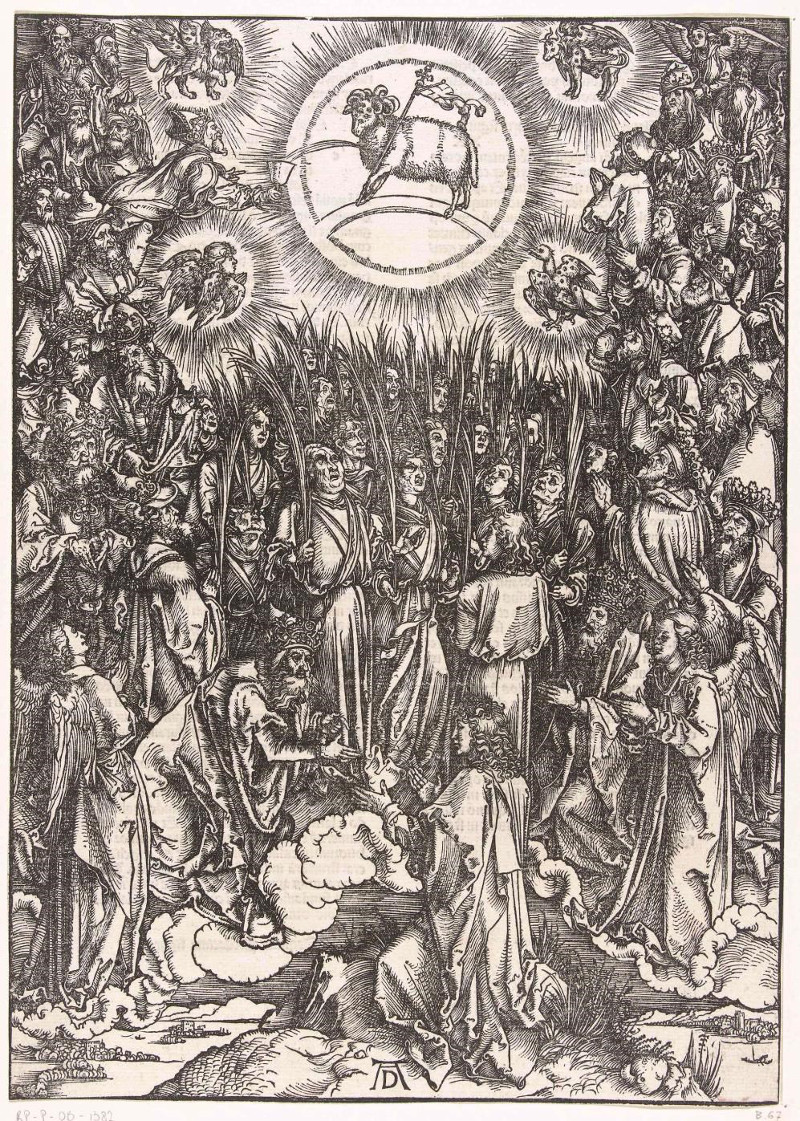

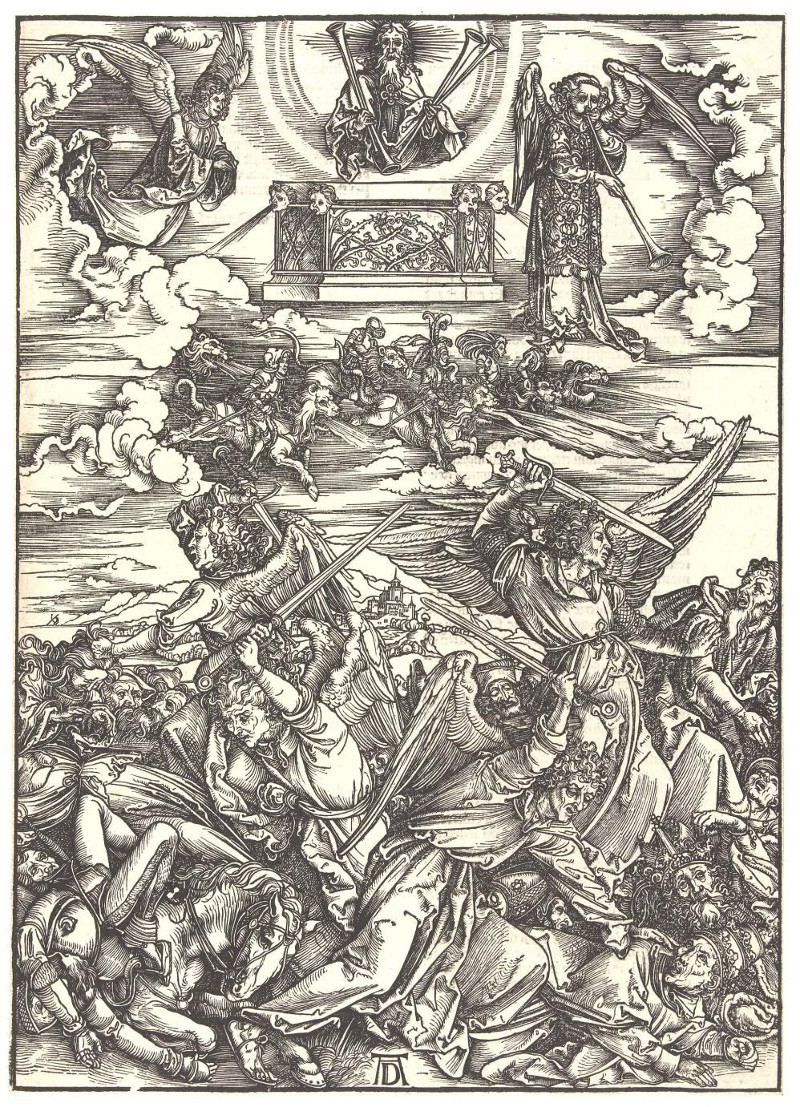

We shall now show some

characteristic examples of Dürer's drawings — etchings and

woodcuts. To begin with, from his cycle on the Apocalypse —

fifteen leaves, done in 1498.

27. Dürer. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

(1498.)

28. Dürer. The Woman Clothed with the Sun and

the Seven-headed Dragon (1498.)

29. Dürer. The Adoration of the Lamb and The

Hymn of the Chosen. (1497).

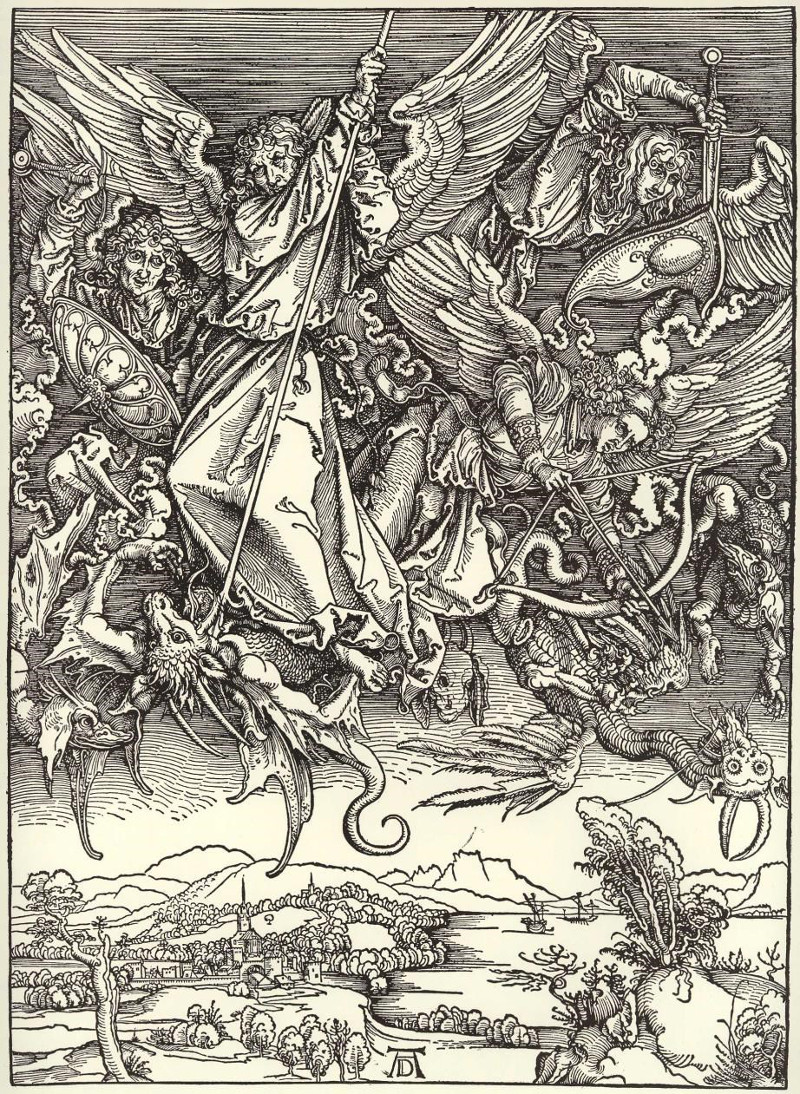

30. Dürer. The Battle of the Angels. (1498.)

31. Dürer. Michael and the Dragon. (1493.)

And now we will show a number

of pictures from the series of etchings of the Passion — known

as the “Kupferstich-Passion.”

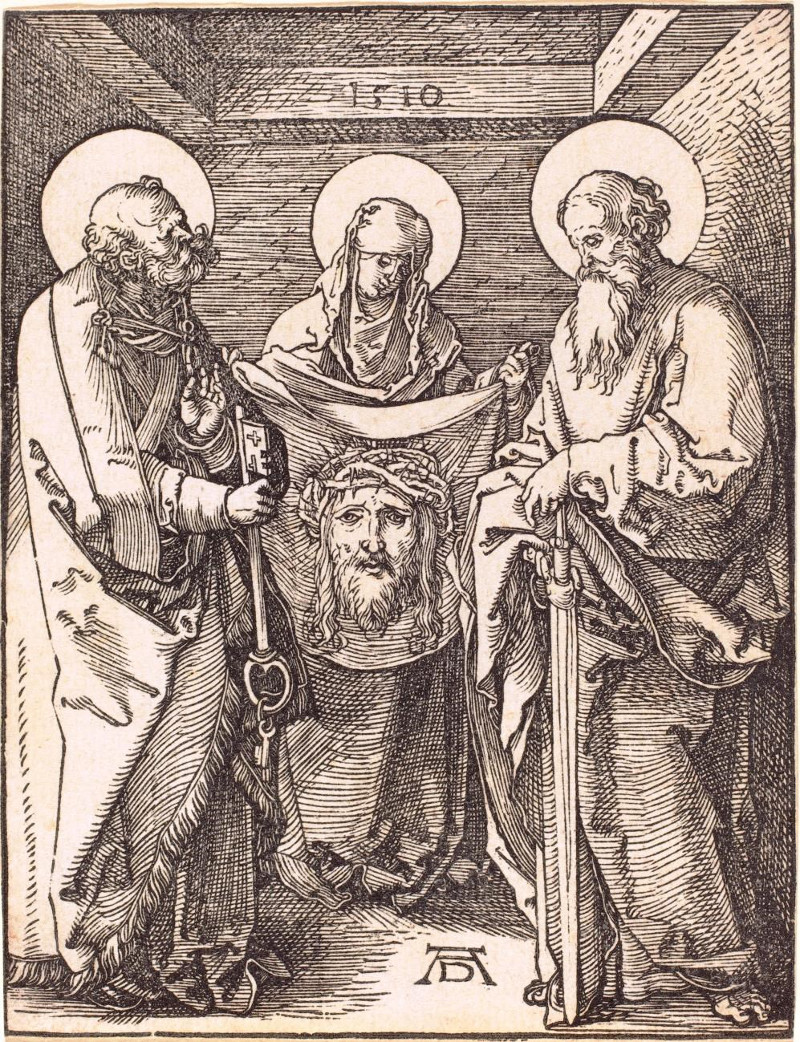

32. Dürer. The Kerchief of St. Veronica.

(Etching)

Then the motif that occurs

again and again in that time: —

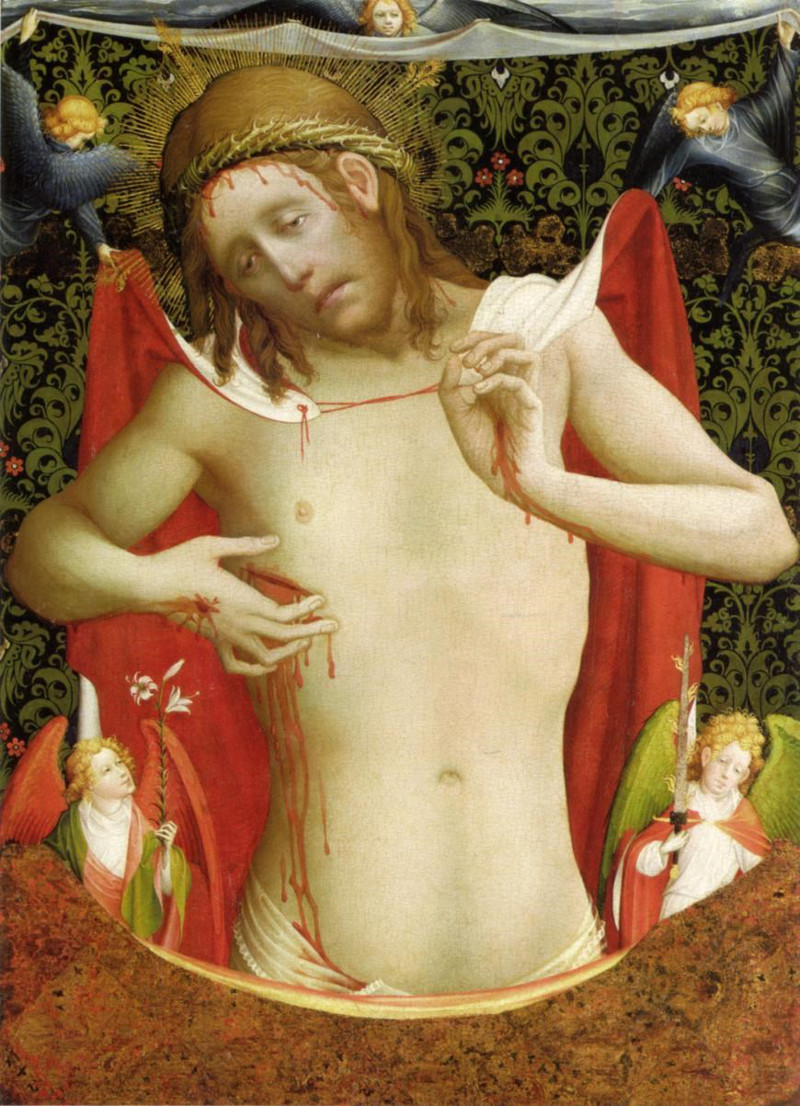

33. Dürer. The Man of Sorrows. (Etching)

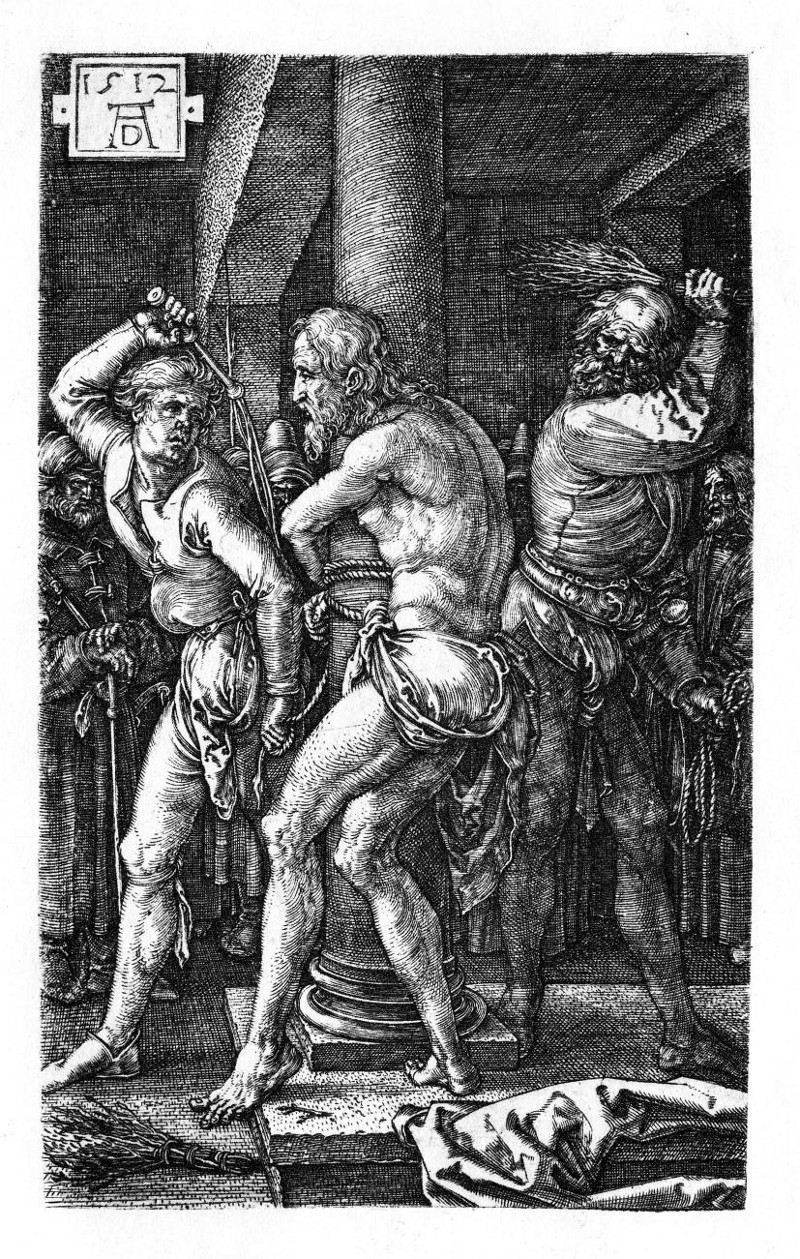

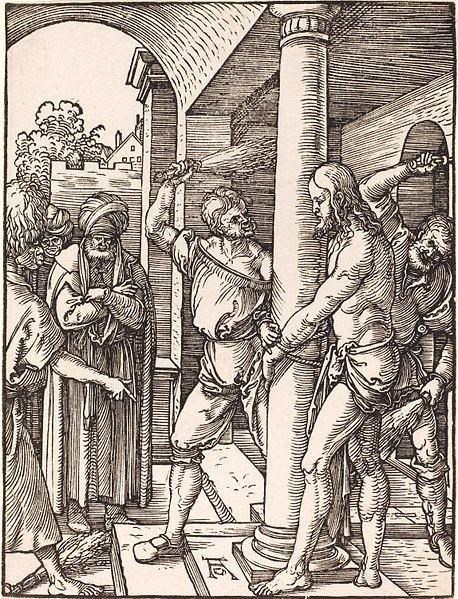

34. Dürer. The Scourging. (Etching)

35. Dürer. The Crowning with Thorns. (Etching)

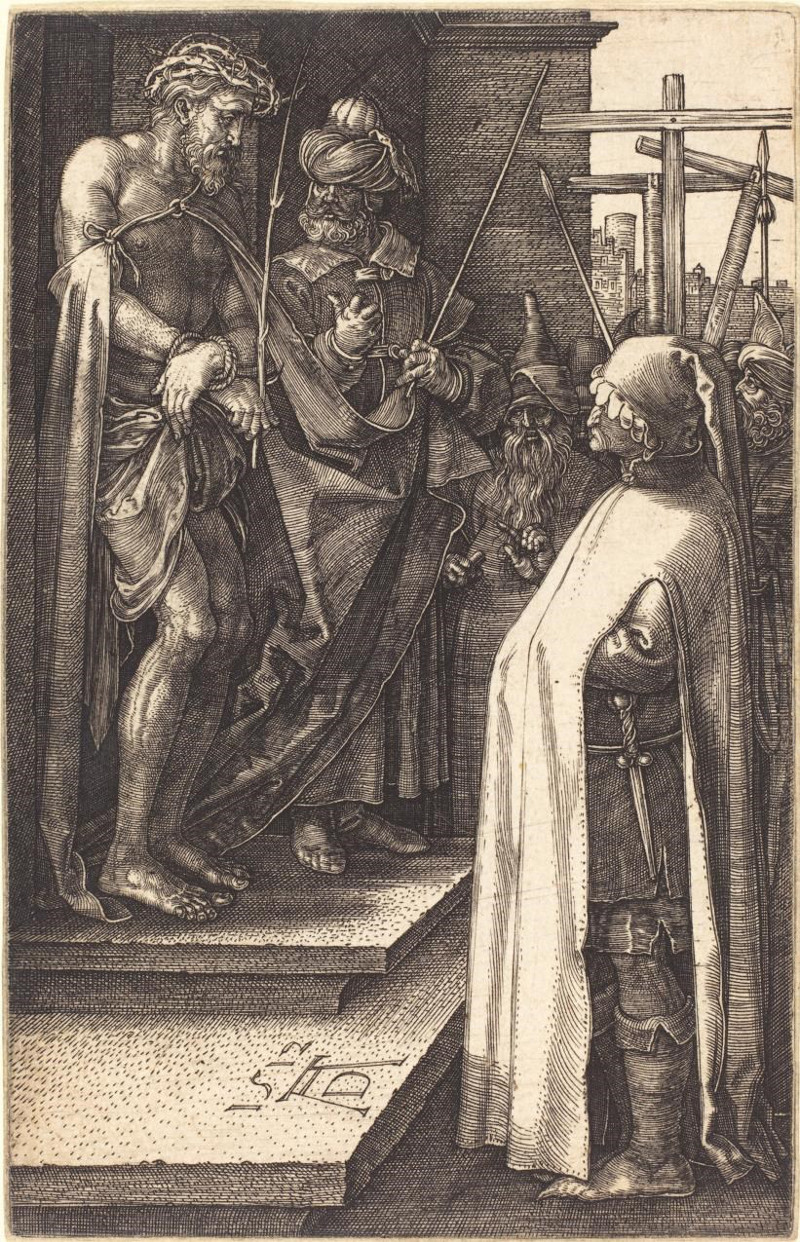

36. Dürer. Ecce Homo. (Etching)

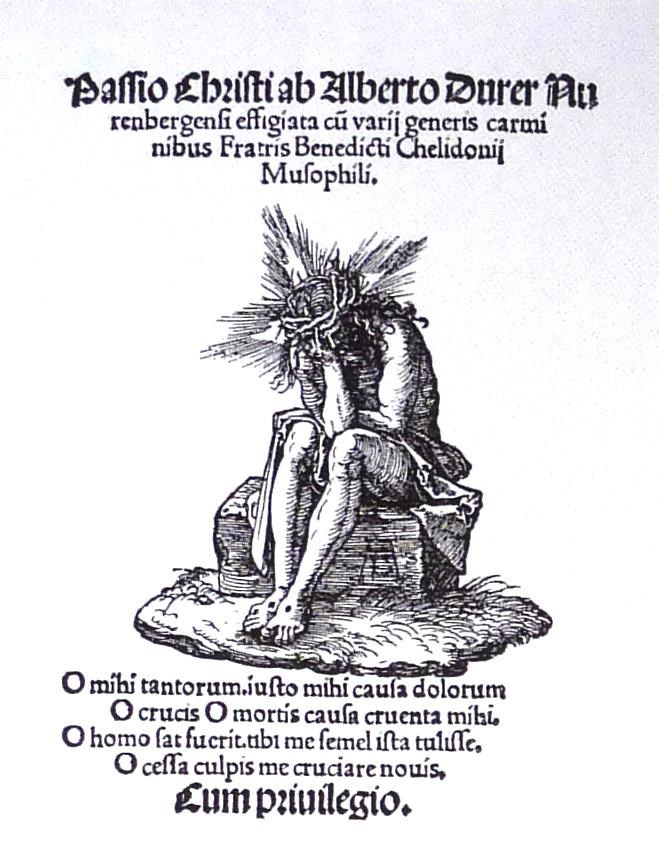

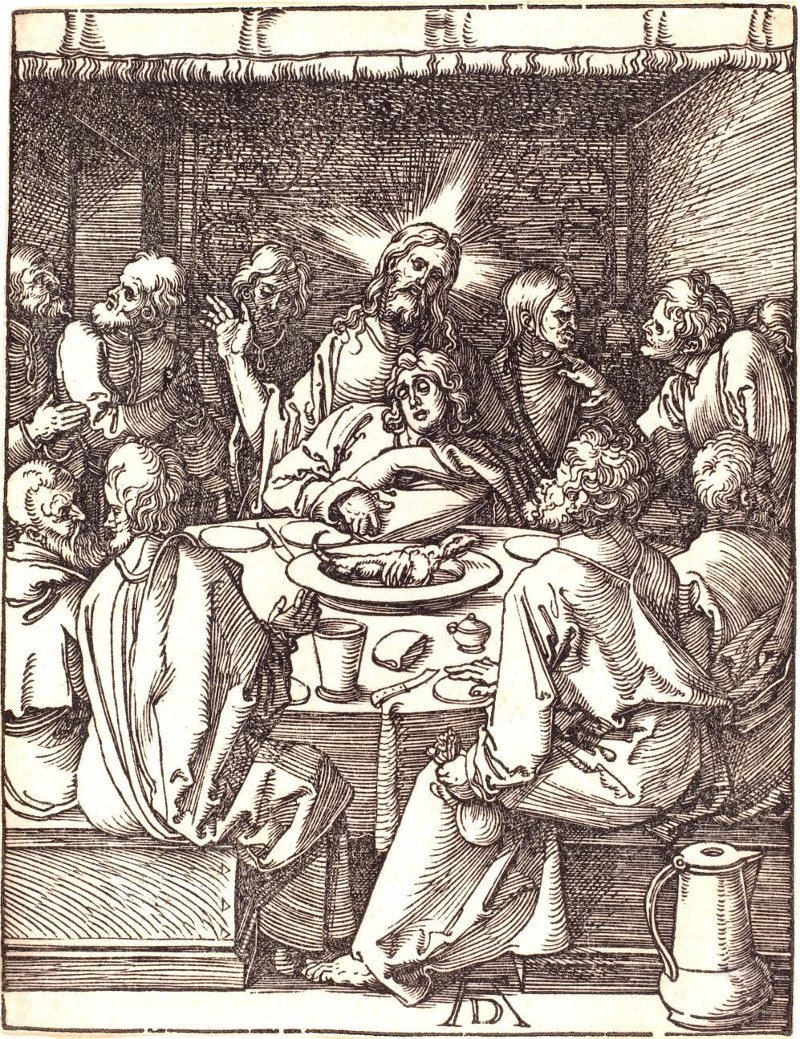

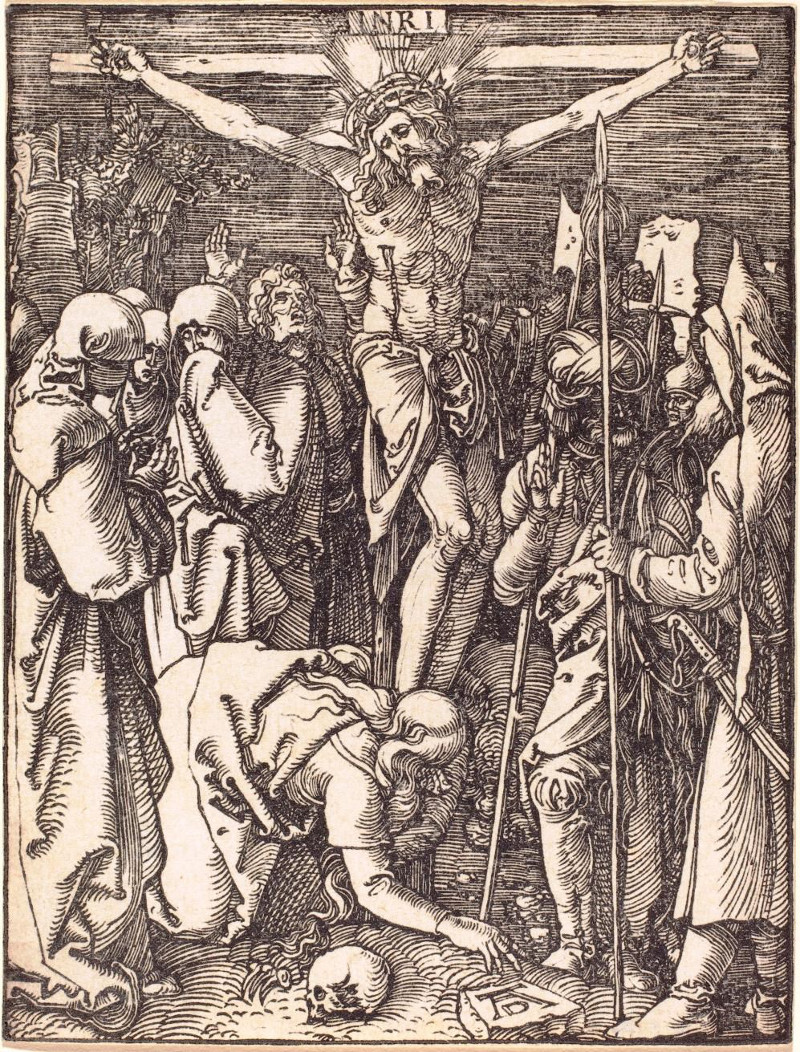

We will next show a number

of pictures from the Holzschnitt-Passion — of thirty-six small

woodcuts. They are extraordinarily tender and intimate. The first is

the title-page: —

37. Dürer. Christ with the Crown of Thorns.

(Woodcut)

38. Dürer. Saint Veronica. (Woodcut)

39. Dürer. The Last Supper. (Woodcut)

40. Dürer. The Scourging. (Woodcut)

41. Dürer. Ecce Homo. (Woodcut)

42. Dürer. The Way to Calvary. (Woodcut)

43. Dürer. Christ on the Cross. (Woodcut)

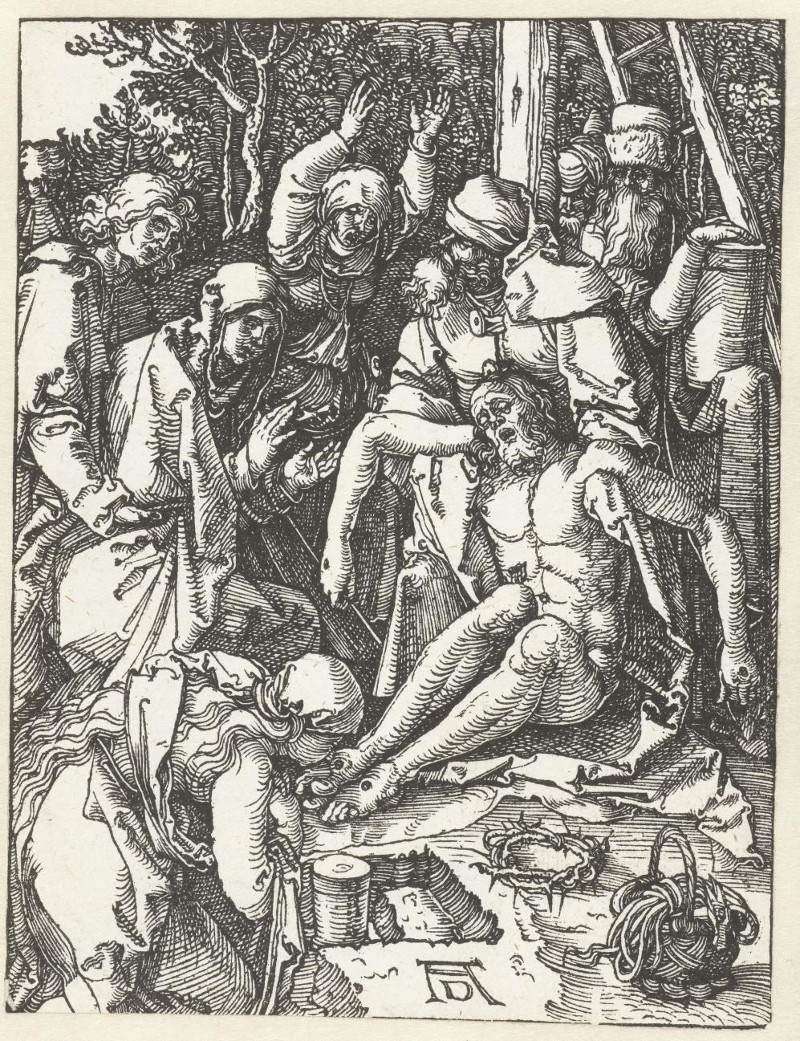

44. Dürer. Mourning for Christ. (Woodcut)

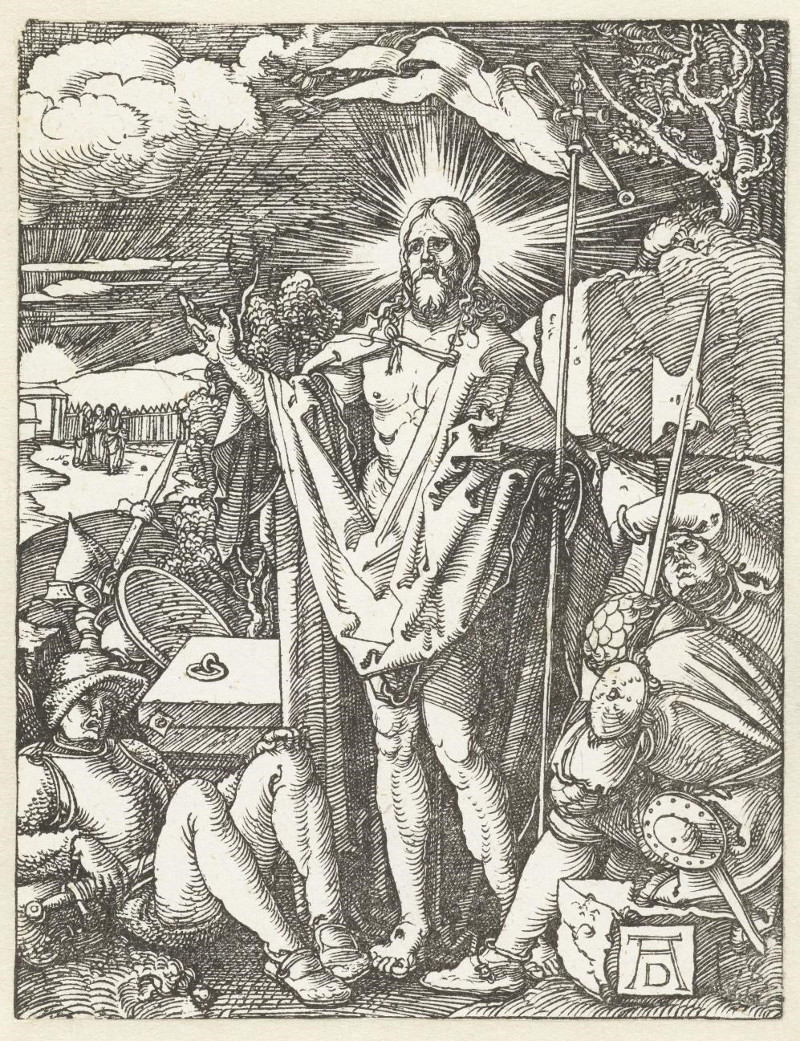

45. Dürer. The Resurrection. (Woodcut)

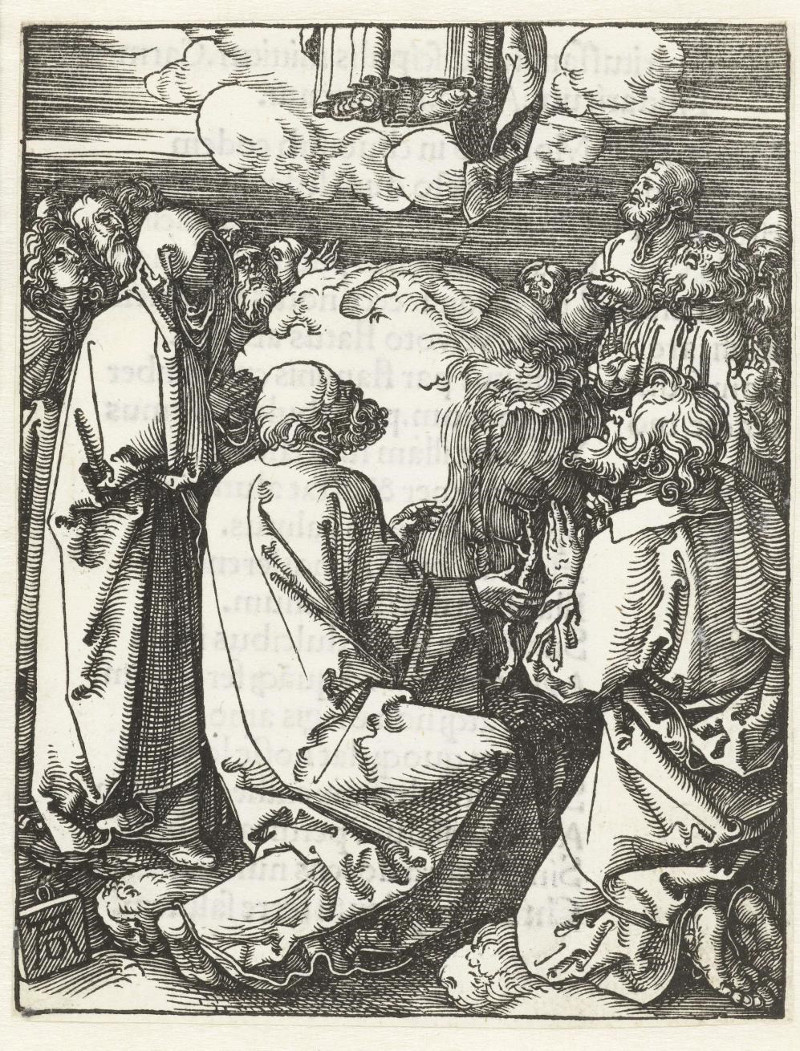

46. Dürer. The Ascension. (Woodcut)

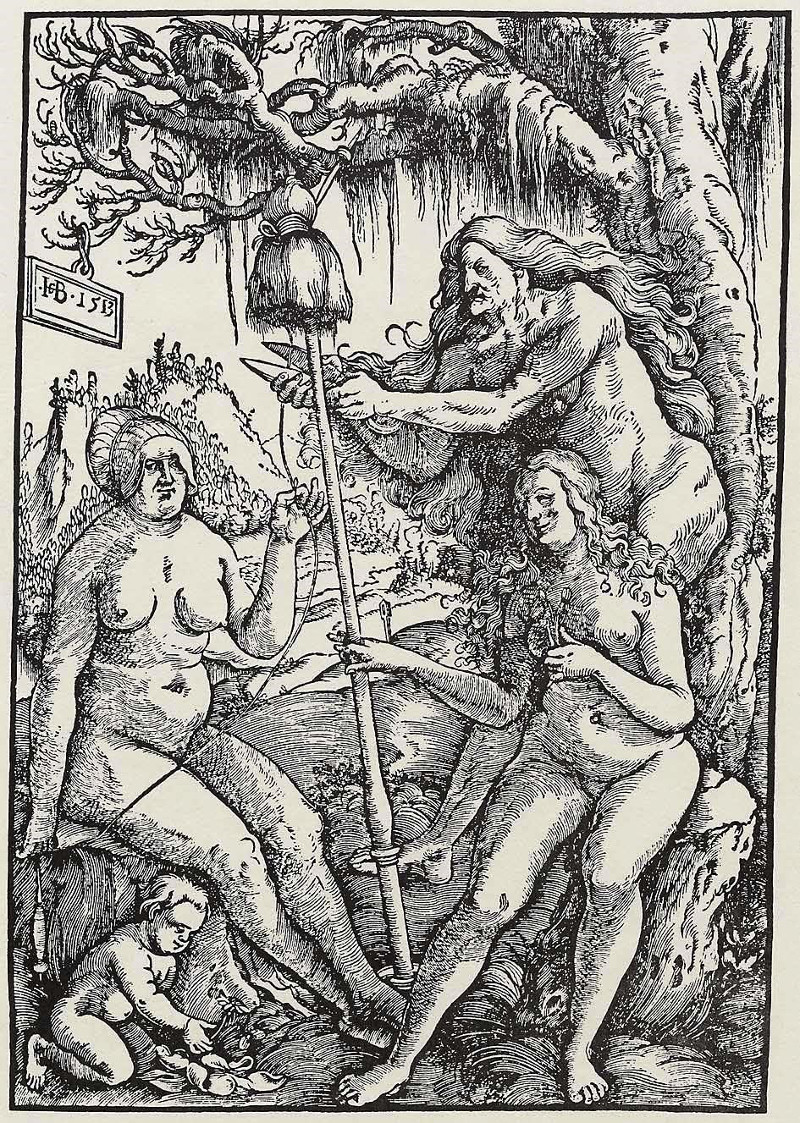

We can also show two pictures

by Hans Baldung, who worked for a certain time, at any rate —

in Dürer's workshop. These pictures date from the end of the 15th

or beginning of the 16th century.

47. Hans Baldung. The Three Fates.

48. Hans Baldung. Ecce Homo.

49. Hans Sebald Beham. The Man of Sorrows.

I would like to make the

following remarks: — The transition from the Fourth to the fifth

post-Atlantean epoch and all that is connected with it, finds expression

— far more than we can realise from the ordinary textbooks of

History — in the whole life of the 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, and

16th centuries. We must remember that at such times, at the turning-point

of one epoch and another, many things are perceptible in the life of

the time, expressing the mighty transformation that is taking place.

History, truly, does not take its course — though the text-books

might lead one to suppose so — like a perpetual succession of

causes and effects. At characteristic moments, at the turning-points

of epochs, characteristic phenomena emerge, in the most varied spheres

of life. Thus, at the transition from the age of the Intellectual Soul

or Soul of the Higher Feelings to that of the Spiritual Soul, phenomena

appear in all domains of life, revealing how men felt when the impulses

of the Spiritual Soul were drawing near. The evolution of the Spiritual

Soul involved the development of those relationships with the purely

physical plane into which men had to enter during the fifth post-Atlantean

age. To a high degree, man was about to be fettered to that physical

plane. Naturally, this brought in its train all the phenomena of reaction

— of opposition and revulsion at this process. Moreover, at the

same time many things emerged out of the former epoch, reaching over

with multitudinous ramifications into the new.

Among the many symptoms

of that time we see, for instance, the intense preoccupation of man

with the phenomenon of Death. In many different spheres — as we

can easily convince ourselves — the thought of Death came very

near to men. Death as a great mystery — the Mystery of Death —

drew near to men at the very time when their Souls had to prepare to

come out most of all on to the physical plane of existence.

Moreover. the things of

the fourth epoch were reaching over into the Fifth. There were the excesses

of the Papacy which had degenerated more and more into a pure impulse of

might. There were the excesses connected with the old divisions — the

riches of the higher orders, their overweening arrogance, their growing

superficiality of life, — while the religious themes themselves

were being made external, flat and superficial. Those human beings,

on the other hand, who attained some inwardness of soul were pondering

deeply on the penetration of the Spiritual world into the physical.

Added to this, there was the absolute need to turn one's attention to

the spiritual world; inasmuch as the seeds of decay and destruction

were entering most terribly into the physical world just at that time.

For in those centuries the plague was raging far and wide in Europe

— truly, an awful death, Death, in the Plague, came face to face

with men as a visible phenomenon in its most awful form.

In Art, too, we see this

intensive study of the significance of Death. It comes before us especially

in the famous Procession of Death on the cemetery wall at Pisa —

one of the earliest appearances of this kind. Then we find many pictures

of Death as it draws near to men under the inexorable laws of Fate —

draws near to man of whatsoever rank or class. The “Dance of Death,”

the “Wandering of Death through the World,” Death's entry

into all human relationships — this becomes a very favorite theme.

It was out of this mood and feeling that Holbein himself created his

cycle on the Dance of Death, three examples of which we shall now show.

In Holbein's Dance of Death the object was especially to show how Death

approaches the rich man, for instance; approaches man of every social

rank — from the highest in the land to the lowest. Moreover, the

object was to show Death as a righteous judge. Holbein in his Dance

of Death desired to show every conceivable circumstance under which

Death draws near to human life.

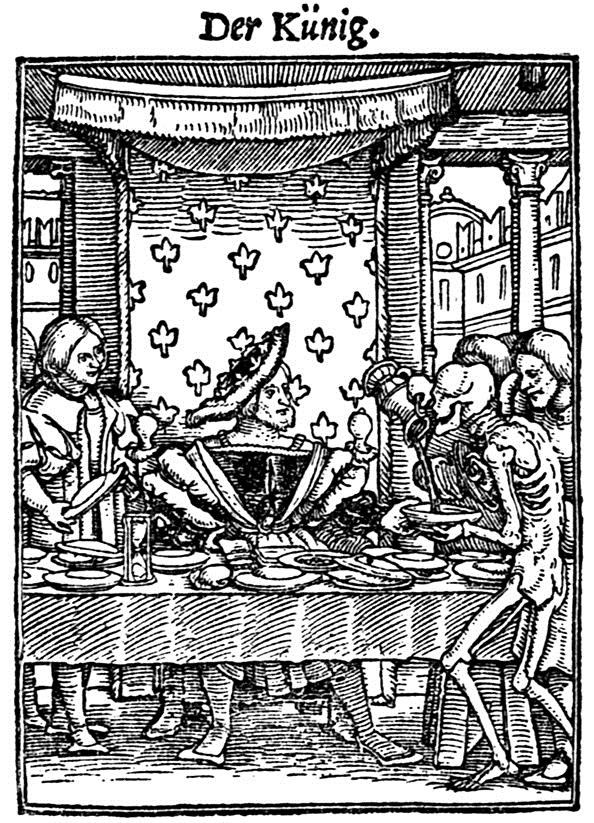

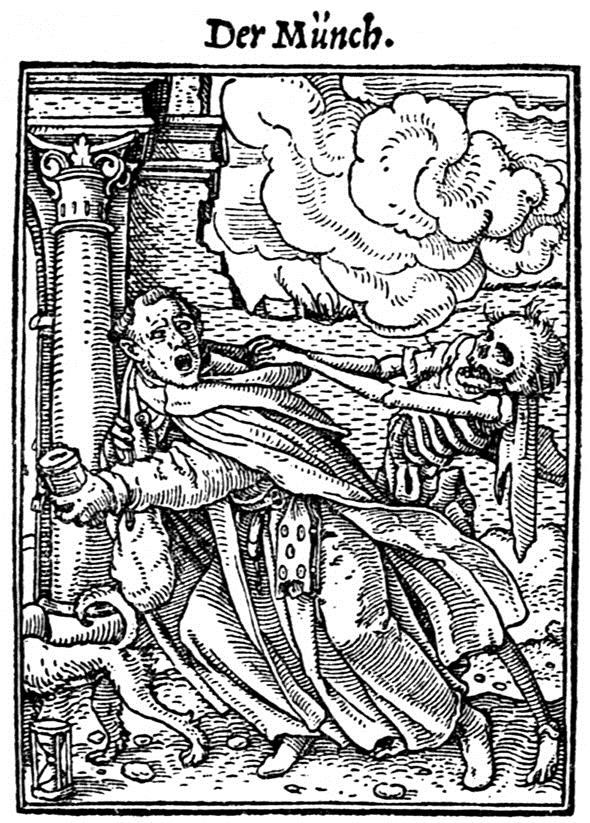

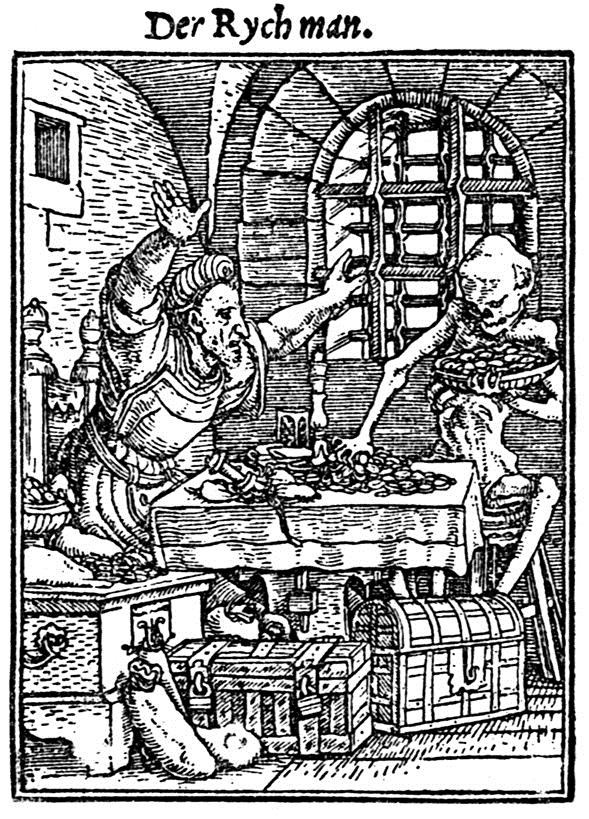

44a. Holbein. Death and the King.

Here we see Death coming

to the King, to tear him away from his royal life.

44b. Holbein. Death and the Monk.

The people of that time

had great delight in pictures such as these. This was the time when

the Reformation strove to put an end to all the growing worldliness

and emptiness of the religious life — to the corruption of the

Church and the religious orders.

45. Holbein. Death and the Rich Man.

Death draws near to the

rich man, and finds him with his pile of money.

My dear friends, we have

seen how the German Art came to expression in these great examples —

and especially in the greatest, in Dürer, — at the end of

the 15th and beginning of the 16th century. One question cannot but

interest us again and again: How is it with the origin and evolution

of this special stream of Art? In order to say a little more upon this

subject, we shall presently show a few pictures revealing how the several

factors stood at a characteristic moment. We can make very interesting

studies on the evolution of the Mid-European or German Art — and

notably the Southern German Art — at the beginning of the 15th

century. True, the pictures of the period, which we shall show, give

only the outcome of a long line of evolution. But this outcome appears

in them strongly and characteristically. When we wish to characterise

a great range of phenomena, we have to sum up many things in a few words;

and if we desire to be true, it is by no means easy ... It may be

that the characteristic pictures we choose does not fully represent

all that is here intended. But if we take things on the whole, we shall

find it is confirmed, undoubtedly.

The origin of the Mediaeval

Art of the German people shows itself most characteristically on the

slopes of the Alps reaching out into Southern Germany, into the regions

of Southern Bavaria and Swabia. And we must realise that here was a

flowing together of two factors. The one represented by all that was

imported from the South along the paths of evolution of the Church —

and notably the Roman Church system. We must decidedly imagine (though

the historic documents contain little about it) that in artistic matters,

too, many an impulse came through the Church and the clerical orders.

This applies especially to the districts to which I have just referred.

Undoubtedly, many priests and clerics also became painters — good

and bad — and they, of course, were always in close connection

with the whole system of the Church, working its way upwards with its

Roman, Latin impulses from the South. They carried with them all that

was living there as artistic tradition. Needless to say, this great

tradition reached its eminence only in men of genius, but it existed and

was taught as a tradition even among lesser men. Tradition was especially

at home in Italy, and thence the priests and monks absorbed and carried

it with them to the North.

With all the other things

which they derived from the Roman Church, they also took with them these

conceptions of how the artist should work, ideas of artistic harmony

and balance: Of how one ought to group the persons in a picture, and

how the lines should go, and so forth. All this that we see at its loftiest

eminence, say in the works of Michelangelo and, above all, Raphael,

too, did not create naively, but, as I said before, out of a far-reaching

artistic tradition. These artists knew how the figures should be grouped,

in the composition, how the single figures should be placed, and so forth.

And as I mentioned recently, they had brought the laws of perspective to

a high degree of perfection.

All this was taken Northward.

Monks and Priests who had enjoyed artistic training would frequently

discuss such things with those who showed signs of artistic talent.

But it must be said that the people whose home was in the German-speaking

districts of what is now called Austria or Southern Bavaria or Swabia

absorbed these rules of Art only with great reluctance. There can be

no doubt about it; they confronted many of these things without real

understanding. They heard that a thing must be done so, and so; but

it did not truly appeal to them, it did not strike home. They had not

yet developed in themselves a vision for these things. For a period,

from which little has been preserved, we must assume, proceeding from

these districts, works of Art carrying forward in a very clumsy fashion

whatever had to do with the great artistic tradition of the Latin, Roman

South. They could not enter into it; they had very little talent for it.

The talents of the people of these districts lay in another direction.

I have spoken of all that

was carried Northward by the Roman priesthood. This, as I said, was

the one factor. The other was what I would call the elemental originality

of heart and mind of the human beings themselves who in these regions

showed any kind of talent for the Art of painting. They had no talent

to follow the rules which were considered the highest requirements of

Art in the South. To begin with, they had no eye for perspective. That

a picture must somewhat express the fact that one figure is standing

more in the foreground and another towards the back, — this they

could only understand with great difficulty. To the people of these

districts in the first half of the 15th century the spatial conception

was still well nigh a closed book. Yet these very districts are in many

respects the source and fountainhead of German Art. They could not work

their way through to feel the laws of perspective independently and

of their own accord. At most, they felt that the things must somehow

be expressed by overlapping. The figure that overlaps the other is in

front, the other is behind. In this way they tried to bring some measure

of spatial order into their pictures, and so they began to find their

way into the laws of space.

Primitive as they still

are, we see in these pictures — appearing so characteristically

in the first half of the 15th century — how hard it is for that

stream of evolution which tries to take shape out of the elemental forces

of the human heart, to discover for itself the laws of artistic creation.

We will now show some examples from the above-mentioned districts. We

shall see that they had no real inner relation to the tradition that has

been brought to them. They absorbed it, as it were, unwillingly, with

reluctance. Nor had they yet the power to obey the laws of space out of

their own understanding. To begin with, I will show you an artist of the

first half of the 15th century: Lucas Moser.

46. Lucas Moser. The Voyage of Mary and Lazarus.

(Altar-piece at Tiefenbronn.)

46. Lucas Moser. The Voyage of Mary and Lazarus.

(detail)

Here you see how difficult,

how well-nigh impossible the artist finds it to escape from the flat

surface. He seems quite unable to obey any kind of perspective law.

He creates out of the elemental forces of heart and mind, but his figures

are in the flat — he can scarcely get out of the plane. It is,

however, interesting for once to see something so primitive.

Lucas Moser was one of those

artists, creating within a social order wherein undoubtedly some of

the laws and canons of Art, that had been introduced from the South,

were living. Some element of the Southern style undoubtedly plays into

his works. At the same time he tries to contribute something of what

he sees for himself. And the one thing does not quite agree with the

other. For one does not actually see things in accordance with the laws

of Art.

Look at this Voyage of the

Saints across the Sea, as it is called. Look in the foreground (although

one can scarcely speak of a “foreground” here), — see

the water in which the ship is floating. The waves are merely indicated

by the crests, painted in lighter color. If you try to imagine a visual

point from which the whole picture might be seen, you will get into

difficulties at once. We must imagine it high up so as to look down

on the water. But that, again, will not agree with the aspect of the

figures of the saints, below.

On the other hand, you see

this artist is already striving towards what afterwards emerged —

as their essential greatness — in the German artists of a later

time, whom we have now considered. Look at the element of naturalism

— the faithful portrayal of expression in the faces of these saints.

And yet they are sitting on the very edge of the boat, so that they

would certainly fall overboard at the least breath of wind. In spite

of this, how intimate is the artist's observation; how delicately the

souls are expressed. He makes an unskillful attempt to observe the laws

of Art, and tries to be realistic at the same time, and the two things

do not agree ... Needless to say, the face could not be in this position,

in relation to the body (see the figure of the saint, with the mitre).

There are countless faults of the same kind. It is all clue to the fact

that the artist is striving on the one hand towards what afterwards

became the real greatness of the German Art, while on the other hand

he is impressed with certain rules. For instance: That there should

be a full-face figure in the middle of the picture, and others in profile

to contrast with it. He has been taught certain rules in arrangements

of composition. All this he tries his best to observe. But he can only

do so according to the measure of his own elementary conceptions. He has

not yet worked his way through to any kind of perspective or observation

of the laws of space.

Observe these little hills,

— and yet the picture does not really recede towards the background.

You will realise the immense progress that has been made by the time

of Dürer and Holbein. And yet how short was the intervening time!

This alter-piece was done in the first half of the 15th century. How

strongly the forces must have worked, overcoming the artistic traditions

imported from the South (for these they did not want) and bringing forth

a new stream out of an independent elemental impulse. They rebelled

against the Southern tradition and tended to overcome it, and to find

for themselves what they required. And you have seen how far they got

in a comparatively short time.

We will now show another

picture by the same artist.

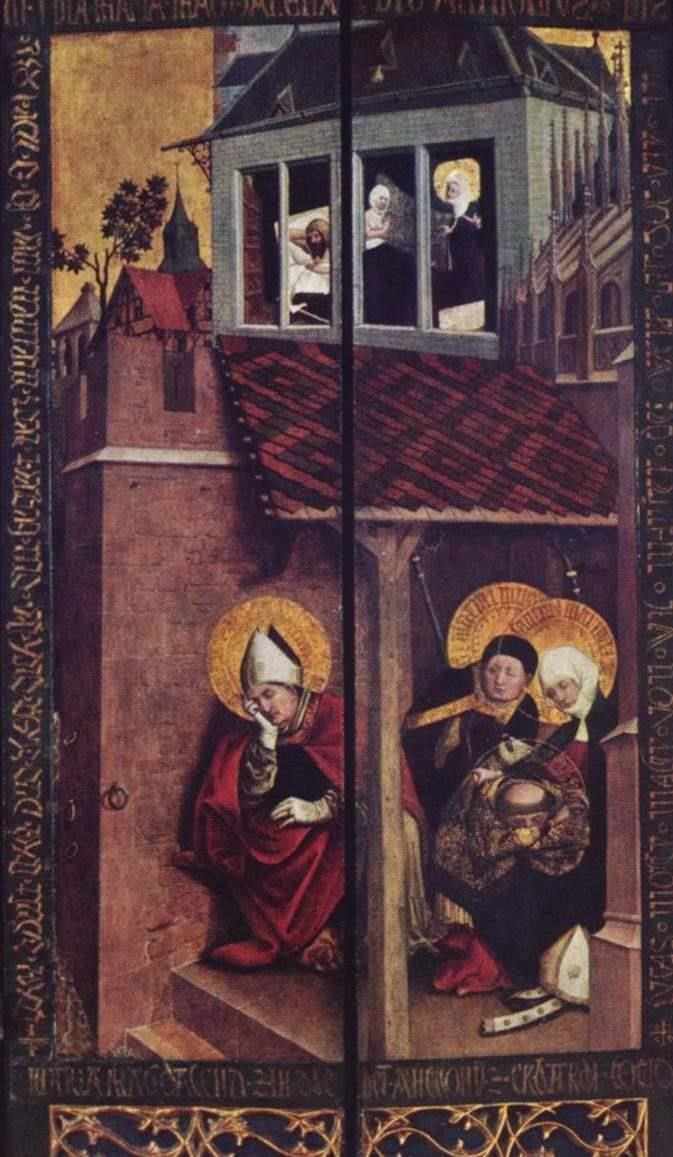

47. Lucas Moser. Saints Asleep. (Marseilles.

From the Altar of Tiefenbronn.)

Look at this creation! It

shows how the artist combines a clear vision of Nature with an absolute

disregard of some of the simplest natural facts. The tiled roof and

the church tower — the whole ensemble is such that the artist

cannot possibly have seen it anywhere. He just puts it together, having

learned certain rules about the distribution of figures in space. Yet

look how he brings out the single items according to his own vision.

There is a decided beginning of Naturalism. He tries to be naturalistic

and yet to express what he feels should be. His subject is "Sleeping

Saints," but he conceives that they must appear worthy and dignified.

Look at the figure of St. Cedonius (?) here, with his mitre.

48. Lucas Moser. Saints Asleep. (Detail)

49. Lucas Moser. Self Portrait. (Detail)

Once more the whole thing

seems on the flat. But you will already observe the first attempt to bring

out of the spatial effects by the strong shadows thrown. His relations to

the laws of perspective are very strained, to say the least. But he

contrives to get the effect of space by the strong shadows, and altogether

by the distribution of light and dark.

This, as we saw in former

lectures, is a peculiar characteristic of the German stream, —

to feel the quality of space by catching the light, using the spatial

virtue of the light itself. Here we do not take our start from the laws

of lineal perspective — laws of perspective drawing. We extend

the surface forward and backward by discovering the hidden effects of

light itself.

We can see this most

significantly in another artist, who already seeks for truth of Nature,

but can still be characterised fundamentally in the same way as the former

one. I refer to Multscher.

50. Multscher. The Nativity. (Berlin.)

Here is a representation

of the Birth of Christ. Once again there is really nothing of those

Laws of Space that came from the South. But you see the beginnings of

the spatial working of the light itself. Space is born, as it were,

out of the activity of light, and in this element the artist works with

keen attention. This picture dates from 1437.

In Moser's and Multscher's

works we have a true artistic impulse, born out of the very nature of

the German South. Here is the element that afterwards rose to its height

in Dürer, Holbein and the rest, though the latter were also influenced

from Flanders and the Netherlands. The Cologne Masters, too, are rooted in

these same impulses. Again and again we see how wonderfully the

characteristics emerge even at the very beginning of the evolution of such

an impulse. Observe in this picture the striving to express the inner

quality of soul of every single person. And yet the artist's relation to

certain other truths of Nature is very strained; Imagine you were in this

crowd of people standing in the background. Look at the faces. Considering

how near some of them are, they could not be standing side by side in

that way unless their arms were chopped off, right and left; the artist

pays no heed to these elementary matters of spatial distribution. One

person is dovetailed into the other. The next is another picture by

Multscher.

51. Multscher. Christ in Gethsemane. (Town

Hall. Sterzing.)

The artist tries to find

his way into the representation of landscape. Note how deeply he has

felt the three figures of the apostles, left behind. Yet how little he

succeeds in making any real distinction between foreground and background.

He seems almost unable to follow any of the laws of space. But he tries

once more to express the spatial by the effects of light. Here once

again we see the element which afterwards became so great in German

Art.

52. Multscher. The Entombment. (Stuttgart.

Museum.)

In Lucas Moser and in

Multscher we see the actual beginnings of German Art. There are others,

too, but very little has been preserved; most of it is to be found in the

churches. With all their primitive unskilfulness, we have here the

beginning of what emerged with real greatness in the pictures of a

later date, that we have seen. They paint out of a primitive feeling,

while they simply cannot find their way into the traditions that come

to them from the South. Their inwardness is in opposition to these laws

in which they are instructed. One more picture by Multscher.

53. Multscher. The Resurrection. (Berlin.)

All that we have said of

the two artists comes out very prominently in this picture. If you look

for a point from which these figures with the sarcophagus (for so we

might call it) are seen, you have to look high up above. We are looking

down on the whole scene. And yet if you look at the trees you will see,

they are seen from a frontal aspect. There is no single visual point

for the picture as a whole. The trees are seen from in front; the picture

as a whole, from above. There is no single point of vision according

to the laws of space. Indeed, whatever of perspective you do see in

the pictures would largely be eliminated were it not for the strong

differentiation of the space through the effects of the light itself.

In this respect, our eyes will easily deceive us. You would look in vain

for line perspective in this picture. You would find mistakes everywhere.

I do not mean naturally admissible mistakes, but errors which by themselves

would make the picture quite impossible. We see once more the striving

to get beyond the mere linear perspective by means of a spatial depth

and quality which the light itself begets.

We see how these artists of

Middle Europe have to feel their own way towards a totality of composition.

There is another interesting point, — less evident in these pictures,

but you will find it in other works by Multscher belonging to the same

altar-piece. His fine feeling for light enables him to bring out the

facial expression beautifully. But he is scarcely able to do the eyes

with artistic truth. You can see it here to some extent, though it is

less evident than on other pictures. And as for the ears — he

does them just as he has been taught. Here he does not yet possess a

free and independent feeling. Thus on the one hand he observes what

he has been told, but without much artistic understanding. The things

he does according to tradition he does badly. On the other hand, we

see in him, in a primitive form, what was only afterwards able to appear

more perfectly in German Art.

It is, indeed, remarkable

how all these things, which we find in the German Art, emerge already

in a highly perfect form in the Hamburg Master, Meister Francke, who

was practically a contemporary of Moser and Multscher.

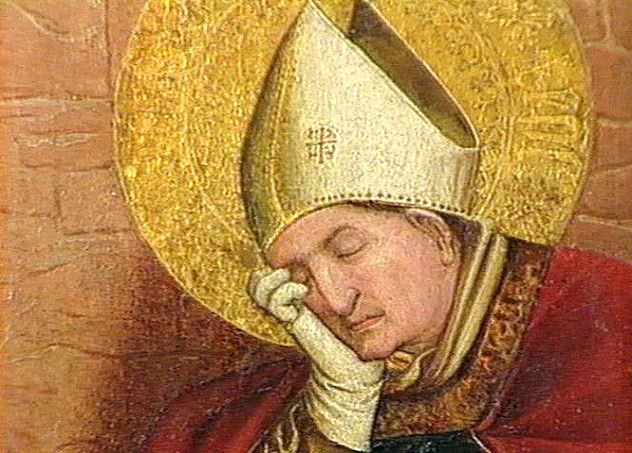

54. Meister Francke. The Man of Sorrow. (Hamburg.)

In this Ecce Homo, this

Man of Sorrows, you see how high a degree of perfection the expression

of the Head of Christ, which was elaborated by and by in the course

of time, had already reached. Compare this Head of Christ with the one

by Multscher which we saw just now. You will recognise a great advance.

Likewise, in the whole forming of the figures. Of course, the peculiar

quality which afterwards came out through greater skill and variety

of technique in Dürer's work, — in his paintings, etchings

and woodcuts, — is lacking still.

55. Meister Francke. The Resurrection. (Schwerin.)

All in all, considering

the artistic developments that are potentially there in these first

beginnings, and that produced Dürer and Holbein and the others,

we must admit that the thread is broken. For afterwards there came a

break; they turned back again to the Roman, Latin principle. And in

the 19th century, artistic evolution was decidedly on a retrogressive

path. There can, however, be no doubt that this fact is connected with

deep and significant laws of human evolution. This stream of evolution

in Art works out of the element of light and dark, and discovers —

as I tried to explain in the lecture on Rembrandt — the inner

connection of the world of color with the light and dark. Through the

historic necessity of the time, it could not but tend towards a certain

Naturalism; but it can never find its culmination in Naturalism. For in

this peculiar talent to perceive the inwardness of things, the possibility

to paint, to represent the spiritual Mysteries, still lies inherent.

When I say “inwardness of things,” I mean not merely inwardness

of soul, but the inwardness of things themselves, expressed in the spatial

laws of light and darkness which also contain the mysteries of color.

Goethe, as you know, tried to express this systematically in his Theory

of Color. This possibility, therefore, still lies open and unrealised

in evolution. The possibility to paint the spiritual Mysteries out of

the inner virtues of the world of color, out of the inner essence of the

light and dark. And the possibilities in this direction can be extended

also to the other Arts.

But such a thing can only

be brought about through the inspiration of Spiritual Science, of the

anthroposophical conception of the world. In the none too distant future,

the possibilities that lie inherent in the beginnings of this stream

of Art must all be brought together. To create out of the inner light

— out of the forming and shaping power of the light — will

at the same time be to create out of the inner source of being, and

that, I need not say, can only be the Spiritual. In the portrayal of

the sacred History, this stream in Art could not, in the nature of the

case, attain the high perfection which Raphael attained, for instance.

(Nevertheless, in some respects it attained a perfection of its own

— notably in the great artists whose works we have seen again

today.) But the Spiritual that pervades the works of this Art is still

alive. We must only find the connection of what surges through these

works of Art, with the underlying laws of the spiritual life. Then will

spiritual Imagination and artistic fancy join together and create a

true Imaginative Art.

To some extent, as a first

beginning, this has been attempted in our (Goetheanum) Building. For

this is, after all, a beginning of new artistic impulses. Naturally,

there is something primitive about every new beginning; but we have

ventured, none the less, to strive for something new and in a grander

style. The time may come when people will understand what we have been

striving for in this Building. Then it will be realised why certain

occult impulses that came already to expression in this art which we

have seen today and in the preceding and contemporary sculpture (examples

of which we have also seen) remained to this day unrealised. It will

be understood why a certain break was inevitable in the evolution of

this art. How remote, after all, is that which emerges in the 19th century

in the art of a Kaulbach or a Cornelius from what is living in this

art which we have seen today! In Kaulbach, Cornelius, Overbeck and the

rest, we see a mere repeat of the Southern element. In this art, on

the other hand, we see on all hands a radical rebellion and revolution

against the Latin and Roman.

He who is prepared to look

more closely, will find still deeper connections. Think of the four

pictures by Multscher which we have shown today. They represent, if

I may say so, the native Swabian tendencies in the realm of Art. Here

we find a certain native talent for a flat surface with the help of

light. Anyone who has a feeling for finer, more intimate relationships

will perceive a similar quality in the Philosophy of Hegel — likewise

a product of the Swabian talent, and in that of Schelling, of whom the

same thing may be said, and in the poetry of Holderlin.

This grasp of the flat

surface, but working forth from the flat surface with the help of light,

— we find it not only in the primitive beginnings of this art; we

find it again even in Hegel's Philosophy. Hence Hegel's Philosophy, if I

may say so, makes such a ‘flat’ impression on us. It is

like a great canvas, like an ideal painting of the world. It works from

the surface; and in its turn, after all, it can but be the philosophic

beginnings of what will now work its way — not merely into this

projection of Reality on the flat — but into the full Reality

itself. And this “Reality,” I need not say, can be none

other than the Spiritual.

These things are interrelated

in all truth. What I have lately been trying to describe to you for

other realms of life, with regard to the history and civilisation of

Europe, is wonderfully confirmed, in all detail, in the sphere of Art.

All that we recognised in the lecture the day before yesterday —

the impulses working in the different regions of Europe — you

can trace it again in the life of Art. Bring before your minds again

the art of the Netherlands which we have seen, — coming from thence

into Western Germany. Then consider what we have studied today —

as something growing absolutely and originally out of the German spirit

itself. For the country of which we have spoken today, the soil on which

Lucas Moser and Multscher worked, is, after all, the central region

of the German Spirit. It is here that the German Spirit has evolved

most originally and most truly. Here, too, Christianity was inwardly

absorbed, as though by an inner kinship with the spiritual nature of

the German heart and mind. The absorption of Christianity was a far

more inward process in these districts; and here the original and elemental

gifts of the German nature came forth in the realms of Art. They did

not accept what brought Christianity to them from the South in a form

already marred by Rome; they tried to recreate Christianity themselves

artistically out of their inner heart and feeling.

Such a thing could not emerge

in the same measure in the more Northern regions of Germany without

the coming of an impulse from the South. We see the same thing once

more in the fact that Hegel's philosophy received its quickening from

the Southern region, and Schelling's too; while, on the other hand,

the philosophy of Kant reveals itself quite evidently as a North German

product. The peculiar quality of the Kantian philosophy is not unconnected

with the fact that the originally Prussian districts remained Heathen

for comparatively long. They were brought over to Christianity at a

later period and by a rather external process — a conversion far

more external than in the Southern German districts. Prussia, properly

speaking, remained Heathen till a very late period.

The things we otherwise

recognise in historic evolution — we can find them confirmed in

the evolution of Art and in the evolution of the life of Thought. For

this very reason I wanted to place Moser and Multscher before you at

the close of our considerations for today.

|