|

Art

History as the image of inner spiritual impulses.

Part

of 13 lectures given in Dornach between 9 and 29 October

1917.

Lecture by Rudolf Steiner

Part

4: Lecture 11

The battle of individual artistic representation amidst the

demands of traditions from the South and those from the East

(Icons) during the important incisive time period between the

decline of the 4th and the rise of the 5th post-Atlantean

epoch.

ICONS, MINIATURES, GERMAN MASTERS

Dornach, 15 October 1917

I

think that it is good right now to become familiar with the

most varied areas of life and the laws of existence which I

have been referring to during these lectures. I want to say

these laws of existence take on an importance in their realm of

the spiritual life, an importance of being, which up to now has

frequently not been taken into account in world opinion.

Particularly in our present time it is imperative to totally

understand the current 5th post-Atlantean epoch in

which we stand, with all its peculiarities, in order for us to

become ever more and more conscious of how affective we are

within it. You know of course that we consider the beginning of

the 5th post-Atlantean epoch beginning at the start

of the 15th Century, from about 1413 onward. The

beginning of the 15th Century was a significant,

profound, incisive point for western humanity. The creation of

such an about-turn which came about didn't happen all at once,

it was preparatory. In the first moments of this epoch one only

sees a gradual expansion. Old patterns from the earlier epochs

transform into the new one and so on. Preparations were being

made for a long time which were only really being experienced

as a mighty reversal at the start of the 15th

Century.

If

we want to consider another strong western historical impact in

the centre of the Middle Ages, we may look at the rule of

Charlemagne from 768 to 814. If you wish to visualize

everything which happened in the West to the furthest

boundaries up to the time of Charlemagne, you will have

difficulties with this self-visualization. For many observers

of history today such difficulties do not exist because they

all shear it under the same comb. Only for those who want to

look at reality, will such deep differences exist. It becomes

quite difficult for people in today's world of experiences and

impressions to reach a concept about the completely different

condition of life in Europe up to the time of Charlemagne and

beyond. We may however say that after Charlemagne, in the

10th, 11th and 12th Centuries

a time began in preparation of our own epoch, the

5th post-Atlantean epoch. Up to the time of

Charlemagne old relationships actually flowed which in our

present day, as we have already said, we can't have a true

imagination. Then again preparations were beginning for a new

epoch, and in these three centuries, the 10th,

11th and 12th — it started in the

9th already — events took place in Europe in all

areas of life producing forces which were expressed later,

particularly in the 15th century.

One

can say these centuries just mentioned was a time for

preparation but people today are hardly inclined to refer to

this just as little as they will say Rome is in control of

European affairs. The papacy in the time from the

9th century, before the middle of the 9th

century where the ruling of Europe was so vigorously taken

under control, where all relationships effectively extended,

must not be imagined as the same effective papacy in a later

century or even today. It can rather be said that in those

times the papacy knew instinctively what the most important

areas of life needed, in west, central or southern Europe. I

already pointed out last time that the oriental culture was

gradually pushed back; it had to wait in eastern Europe, in

Byzantianism, in Russianness. There it waited indeed, waited

right up to our present time.

General observations can develop particular clarity in those

areas which, in the broadest sense, one can refer to as

artistic. If you want an idea about what had been pushed back

at the time to the East, what the west, central and southern

Europe should not acquire, if you want to reach an

understanding about it, then compare it with a Russian

icon:

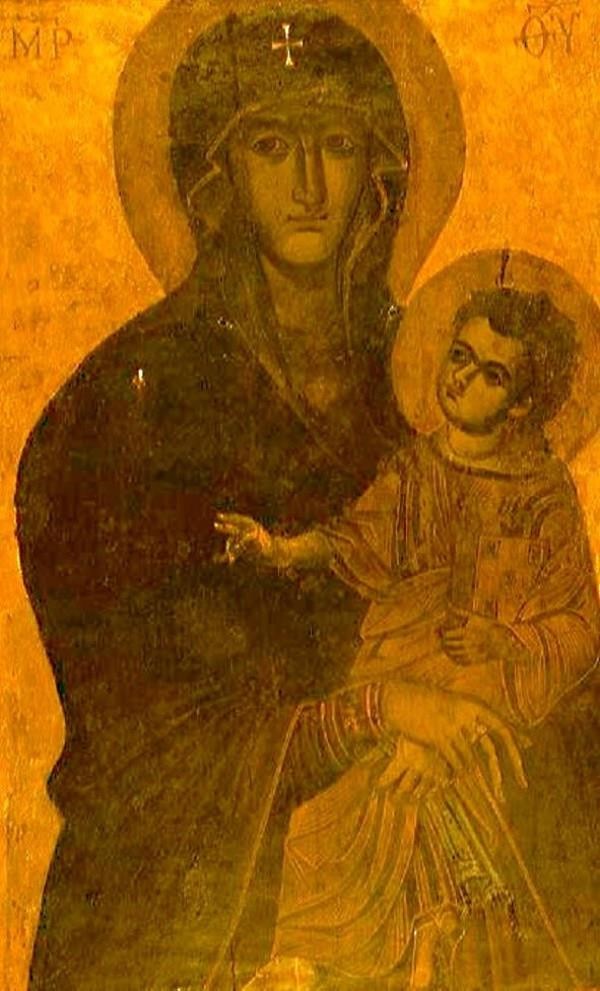

245

Russian Icon: The God's mother by Vladimir (Moscow, Historical

Museum)

245a

Raphael: The Madonna of the Chair (Madonna della Sedia)

(Florence, Palazzo Pitti)

In

the picture of the Virgin Mary of the East is an echo of what

had been pushed back into the East at the time. In such a

picture quite another spirit holds sway than can ever be found

reigning in western, southern and central art; it is something

quite different. Such an icon picture still today presents an

image which has been born directly out of the spiritual world.

If you imagine it in a lively manner you can't imagine a

physical space behind the Russian Madonna image. You can

imagine that behind the picture is the spiritual world and out

of the spiritual world this image has appeared: just so are the

lines, so is everything in it. When you take the basic

character of this image as it is born out of the spiritual

world then you have exactly that which had been held at a

distance in the 9th Century from western, southern

and central Europe:

246a

194 Raphael: The Sistine Madonna: The Madonna with the Child

(Dresden, Zwinger)

246

The Italian Icon: Madonna with the child, image with miraculous

power “Maria Schnee” — Madonna of snow.

Why? Such things should be thoroughly and objectively

considered historically. Why did this have to be held back?

Simply on the grounds that the nations of Europe — central,

western and southern Europe — had completely different soul

impulses which were not in the position to understand humanity

out of original elementary nature, this was being pushed back,

stopped in the East. The nature of the western European soul

was quite differently focussed.

When this which was being pushed back to the East was

transplanted into central, western and southern Europe, it

could only remain external, outside the east of Europe; it

could never grow together with the central, western or southern

European soul distinctions. An area had to be created in

western, southern and central Europe, an area for what

gradually wanted to come out of the depths of the very folk

soul itself.

I

would like to say Rome, in actual fact, understood this with

genial instinct. With disputes regarding dogmatism showing

quite a different character, the content of dogma disputes is

not the real story; the content of these disputes is merely the

final spiritual expression. It goes much further. Among other

things it was about what I have just been characterising for

you. So we see that from the 9th Century and into

the next centuries Rome worked ever more strongly for a space

in Europe where the real striving of the folk souls could

unfold. The striving of the folk souls also appeared in greater

clarity.

You

see, when you focus on what could have been brought to the fore

if the eastern influence had not been pushed back but could

stretch over Europe — Charlemagne made a large contribution -

if it had stretched over Europe then Europe, as I've already

mentioned, would have made available certain observations of

representations which speak directly out of the spiritual

world. This did not happen, firstly because Europe had to

prepare itself for the materialistic 5th

post-Atlantean period which was prepared most intensely in

central Europe. Interest centred mainly on everything other

than what came directly out of the spiritual world like line,

form and colouring. Humanity was interested in something

different. Above all there was an interest in Europe for

contemporary events, for reporting and for results. By studying

individuals, singled out in humanity, you realize they have

positioned themselves in the course of historic, relatable

events. The 10th, 11th, 12th

Centuries can also be called the Germanic Roman Empire because

from Rome the capacity was created, a capacity which spread for

an interest in relating stories, an interest in the working of

time and for conceptualising a particular form set in time.

You

see, this is again a different viewpoint from the viewpoint I

indicated in similar lectures in previous years. This

cooperation of the central European empire with the Roman

church and its spread is an inner image of the way the

5th post-Atlantic epoch prepared central Europe at

the time. From this it is clear that central Europe prepared

itself in this period with very little interest for spatial

educational art. Constituted informative art became borrowed -

just remember the presentation which I gave you in previous

years — borrowed from what came over from the East, spread, one

might say, through to the very joints of principal interest.

What shot up out of the folklore itself was being told. The

content which was to be told had to be taken out of national

character, intimately connected with nationality.

You

can encounter amazing images of central European life, life in

the areas of the Rhine, the Donau and the northern coastline in

the depiction of the songs of the Nibelungen, the Walthari and

`Gudrun'. The manner and way in which these writings are

presented indicate their obvious interest in events of the

time. Look how in the time of Charles the Great when the poem

`Heiland' originated, the stories of the Gospels are woven into

the poem with central European characters, characters extracted

from biblical events and placed directly into the central

European interests of the `Heiland'. It had to be born out of

the life of the European folk soul. Through this the eastern

tradition, which cares little for the temporal and historical,

was pushed back. For this reason, it was pushed back. If we

observe how these concerns of the European nations rise from

deep underground and reach the surface, then it is often only

possible, and with difficulty, to really penetrate into the

depth of feeling, into the deep soul experience which the

European human spirit connected to in its own deepening

encounter with the essential spiritual events. One might say,

that which was pushed back to the East from spatial infinity

and its manifestation out of space, which had to appear

superficially in central Europe should reappear directly out of

the human souls themselves, out of the depths of the soul, not

out of the widths of space — but out of the depth of souls.

The

mysterious prevailing of soul depths under the surface of

direct observation was already something living at that time in

human souls. During the centuries we've been talking about,

people were instinctively permeated with the knowledge that

their souls had in the depths of their being secret impulses,

appearing only sometimes at celebratory moments in their soul

experiences. Life seemed deeper than what the eyes could see,

the ears could hear and so on; something unfathomable rose from

soul depths as a profound experience. I could say we experience

an echo of this kind of thing when we hear something as

beautiful as the poetry of Walthers von der Vogelweide,

who to some extend created an ending to a purely linguistic

age, an age when the ability to depict formless manifestations

in soul depths in a pictorial manner had not yet developed. In

these soul depths we are stirred when we allow Walthers von der

Vogelweide's small poem to work on us, where he speaks about

his own life in retrospect. Maturing as a man when knowledge

grew in his soul and light fell on his soul depths from which

knowledge had previously appeared as mysterious waves in a

dream, now appeared in a mood, he expressed as follows:

“Oh, whereto did all my years disappear!

I dreaming my life or is it real?

What appears for real, was it illusion's face?

I've slept so long and didn't even know it.

I've been woken and all is as unfamiliar

once was familiar, like my own hand.”

Thus speaks Walther von der Vogelweide at the end of the three

long centuries, the 10, 11, 12th centuries, the

epoch in which the Holy Roman Empire blossomed at the close of

this time period. It was the period of time in which the

interest for current events developed. Art demanded expression,

images were to express events happening and going to happen in

central, western and southern Europe. A glance to the East

gives the impression of existence and peace, of a quiet

contemplation out of the spiritual world. Events directly

taking place here, born in the human soul, binding the soul

with the greatest of all, the most mysterious, all this was

eager to be represented in a pictorial manner. Fertilization

from the South was needed anyway, where echoes of all the

traditions having come from the East were still maintained.

Bringing events to expression was the primary goal.

In

this way striving in art was contained in the West, one might

say, in two opposing streams, for certainly the representation

of existence was pushed back East, but only pushed back — many

things remained. Above all, something remained which can be

observed in the East where strict rules determined the

depiction of the icons, and old rules were being adhered to,

where no violation was allowed through lines, expression, and

so on. All this was transplanted into the West and alongside

this was the requirement for everything experienced in the

surroundings, united with traditions coming into central Europe

from the South. Naturally depictions with this requirement

firstly appeared in primitive, simplistic images according to

biblical narratives, Bible stories. Only at the beginning of

the next three centuries, the 13th, 14th

and 15th did a power, one could call it, rise up out

of Central Europe which could depict image-rich pictures. This

power is thanks to specific facts; facts which during these

centuries, the 13th, 14th and

15th, expanded and matured over the whole Central

and Southern Europe as something one could call city

domination, the blossoming of rural development. The cities, so

proud at the time of their powerful autonomy, developed the

particular powers of their folk in their midst. Such cities

were not uniform, either as the old Germanic Roman Empire which

was in decline, nor uniform as in the later state communities,

because these cities were autonomous and could develop their

individual strength according to the needs of the specific

land, lifestyle and place. One doesn't understand the times of

the 13th, 14th and 15th

Centuries if one does not again and again glance at the

blossoming of city freedom at the time.

Let

us visualize this flowering of city freedom — by roughly taking

the 11th to 15th centuries — and consider

what this freedom in the cities discovered in relation to art

impulses. Some traditions originating from Rome remained. The

main issue had been pushed to the East; yet some traditions

remained behind, traditions of alignment, colour application

and, in relation to facial expression, the eyes and nose had to

be done in a certain way. Yet all of that counteracted with the

aim to represent facts. These battles had two sides, we can see

it here where the artistic element first only dares to appear,

turns from within itself outward, where, I might say, the

trained monk from Rome allows himself to be inundated with the

influence from central Europe, the impulse to not merely depict

biblical events but that the imagery appearing in the Bible,

which are glimpses from the spiritual worlds, are depicted in

such a manner that the Bible itself becomes the very expression

of how people live in daily life. This was now imposed on the

monk in his solitary work. When he paints his miniatures and

represents biblical scenes in a small manner, he must be

accountable on the one side for the remains of tradition and on

the other side, what wants to manifest as life under the

surface.

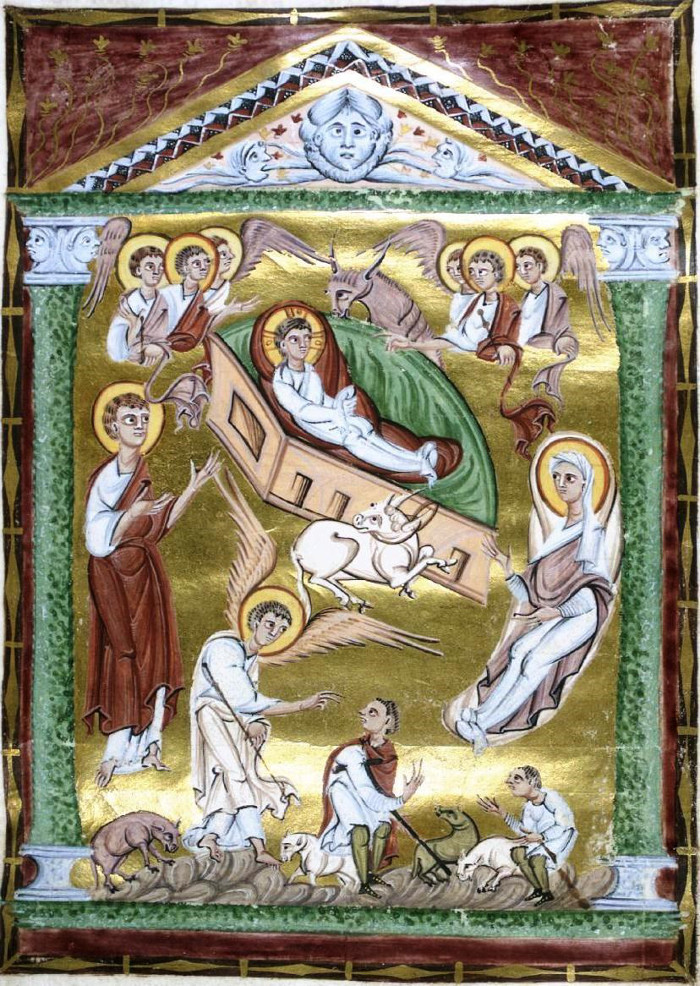

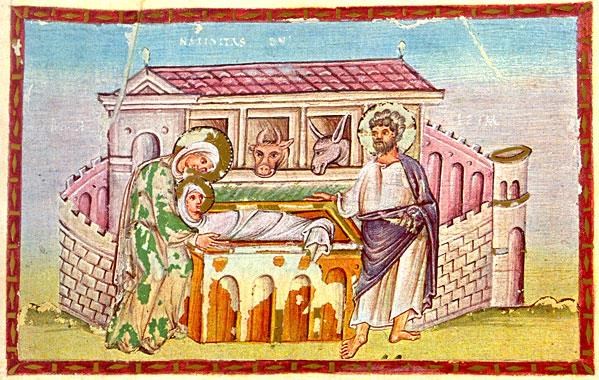

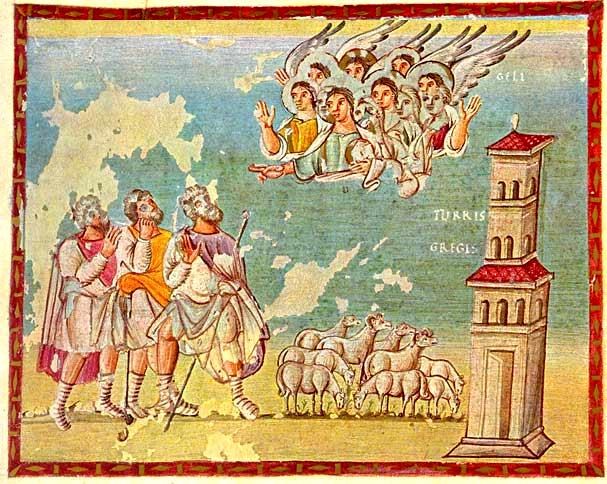

Today I have two such miniatures to show you from which you

will see, how during the 11th, 12th and

also in the 13th Centuries the battle between

traditional painting and history was still visible in small

paintings.

Look at such a painting from an evangelist representing the

“Birth of Christ” — we considered this image in

previous years.

274

Miniature Birth of Christ and the annunciation to the shepherds

(Cologne, Dom Library)

See

how much you are reminded of the tradition of mere existence.

Consider how still here, I might say, these figures are shown

in such a way which does not reflect how people in an outer

naturalistic reality live but observe how the figures are born

out of the imagination people made up of what the spiritual

worlds were for them. From there the saints, the Christ figure

himself appears; all this came out of another world. Behind the

surface of the painting we can only imagine the spiritual world

— of course pictorially and radically spoken.

Above all there is no trace of naturalism. Observe how there is

no trace of perspective, no trace or an attempt in this

painting to somehow represent space — everything is on the

surface, all but intellectual representation. Despite all this,

when you look at the single figures, you experience the urge of

something wanting to be expressed. You will notice there are

two things fighting with one another. Look at the face on the

right and the one on the left and you will see how the eyes,

maintaining something from tradition by the person in his monk

cell had a thought from his teaching that somehow or other eyes

had to be done, this and that way the expression had to be done

— but he battled with it, he adjusted to a certain extent the

view of the situation to the events.

Even in these tiny paintings made in the gospels, in books of

the bible, this battle of the two elements can be seen in a

struggle. Besides this you see again, for example in Cimabue

even more, how existence was expressed in the oriental form.

How we are absolutely reminded of the angel figures above -

which already appear when it comes to Cimabue as an oriental

echo of the conception of the pictorial — as a proclamation out

of the spiritual world itself, as an experience of being, not

of historical events!

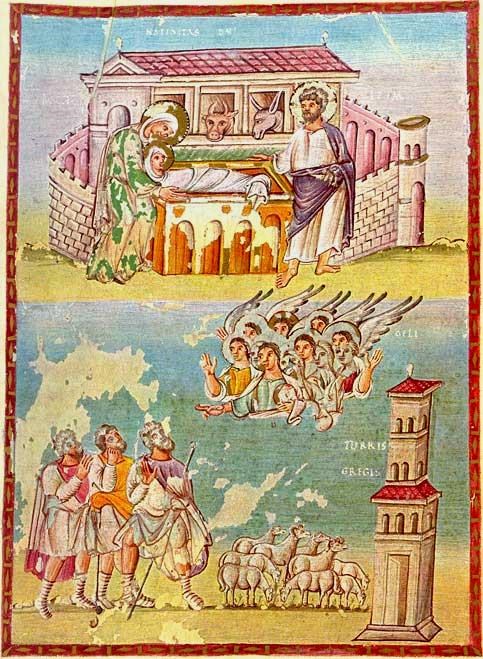

Another test is the second picture, which I have prepared,

which comes from the Trier Gospels:

248

Miniature of Christ's birth: Proclamation to the Shepherds

(Egberti Codex Trier)

Here we see the proclamation to the shepherds, above is

Christ's birth. When you take this shepherds' proclamation of

the angel announcing “Glory in the Heights and peace on

earth to men of goodwill”, when you take this you

discover a mixing of these two impulses.

In

all three of the men's faces we find the endeavour: represent

the facts! On the other side however everything at a distance

is about natural observation; how traditions play into this! I

would like to say, feel how the wings of the angels are in the

book: wings should be depicted in such a manner that they are

at an angle to the main scene, pointing to both sides, and so

on. You sense the requirement and at the same time sense such a

depiction impinges on the endeavour which can't be achieved

according to the observation of historical events. Sense this

and observe in all of them how little nature observation is

apparent, how there is no trace of spatial application, no

trace of perspective in this image, that everything is, I want

to say, or implied in the place where they are depicted due to

requirements of how something like this was to be done, teach,

while still substantially in control.

Now

we see how at the end of the three centuries of the Germanic

Roman Empire the impulse from the establishment of cities to

depict history and unite it with the requirements of

experiential representation, how this urge in Central Europe

came to a sudden and most beautiful flowering. Cologne is one

of those cities where the city's freedom flowered the most

intensively and at the same time had the possibility, through

intensive expansion of the Roman Catholic dominance, to take up

traditional design art coming over from the East. No wonder as

a result that just in Cologne the possibility encounters us in

how, in the most wonderful way this comes together, weaving the

two impulses into one another: the one most ancient and revered

tradition depicted — what a Madonna looks like — and the urge

to represent history. How a Madonna had to look like — in the

East was petrified spiritually, majestic, serene, but still,

solidified. It had to wait. Movement was brought in from the

West. The revelation brought in from above, from heaven,

revealed in the Madonna figure, is to be experienced in the

Russian Madonna as magnificently elevated and permeated with

something one can see directly: the greatest beauty possibly

revealed in a human face, the loveliest direct expression of

the ability to love, human friendliness, human goodwill,

everything living in the surroundings lived in an inner

relationship with the revealed figure of the Madonna.

Consider this and then look at the painting done by Master

Wilhelm:

243 238 Cologne Master: Madonna with the Wicken

flower (Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz Museum.)

Here you can see what I actually want to point out: you can see

how an attempt is made to bring life, that means events, into

being in the Virgin Mary depiction. Here individual observation

merges with tradition right into the details, one might say:

old prescriptions were only applicable to attitude, nobility of

form, serenity but not much further than in the expression of

line, thus tradition was already being experienced from

individual observation. This is what we can admire so much in

these masters.

Another painting by the same master:

237

Cologne Master: Saint Veronica with the sudarium/ Veronica's

veil (Munich, Older Picture Gallery)

Another painting by the same master ... to indicate what I have

just mentioned, shown in another representation. Consider just

how much has come through the traditional heavenly figure, the

revealed form of the Redeemer's face, of Veronica's face, in

which we can see something revealed directly out of soul

depths. See for yourself how those angel faces looking up are

already individualized! Consider how with this image, as a

result of the individualizing of figures it is no longer

possible to actually imagine heaven behind it. However,

something else is possible. At the back of the image, which

came out of the Eastern inclination (245) we can actually

imagine the spiritual world, something in addition to what the

image presents. Here (237) we can also imagine something else;

we must feel something different from what the image depicts.

We feel much of what has gone before due to knowledge from the

Bible; we feel much of what has resulted, events have been

experienced and what is depicted are scenes from before and

after. Thus there is not something like a spiritual realm

behind it; the experience is of something before and something

afterwards. When the singular is represented — visual art does

this after all — then a single element is lifted out of the

events. This is what we find towards the conclusion of every

time period, towards which Rome out of such a deep

understanding through the three to four centuries created in

the European realm, which wanted to rise out of folklore. The

conclusion appears to us and how this works in Cologne, by such

genial Masters being capable of creating something like

this.

These two intertwining impulses which I have characterised flow

together most remarkably here. Now I would like to indicate

their power which had worked everywhere by showing you a couple

of paintings, starting with Constance who probably learnt from

this and many countries through which he travelled, to arrive

in Cologne and gradually became the follower of so-called

Master Wilhelm, Stephan Lochner. The first is the image

of the Virgin Mary — we know it already:

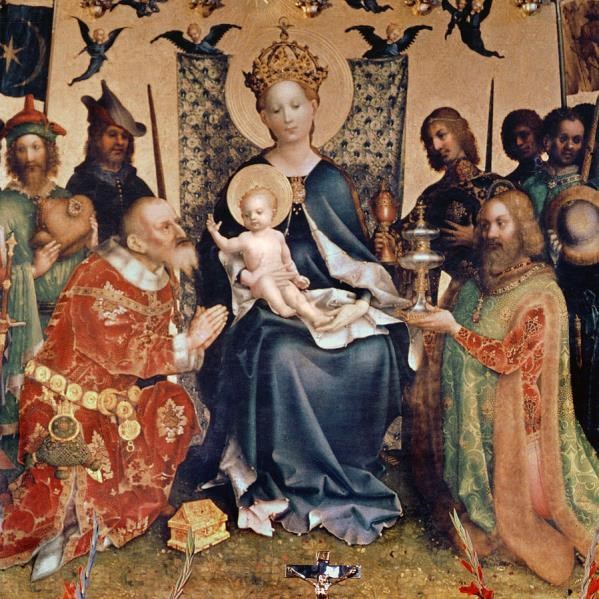

244 239 Stephan Lochner — Adoration of the Magi

(Köln, Dom)

In

this image — you need only compare the single heads — you

already notice the individualizing impulse which is fully

expressed by the figures. This aspiration you can observe. You

hardly see a tendency to use space; everything is on one plane,

you see no possibility of somehow applying perspective, but you

see the yearning, the desire and instinct which can be declared

as events, fixed in the imagery, you see the desire

characterized; you see the past and what will follow

established in the imagery as a scene.

Now

I ask you to look at the two preceding demonstrated paintings

(237,238) by the Cologne masters which appeared when these

masters were blossoming, somewhat around the years 1370 to

1410, therefore directly during the time the fourth

post-Atlantean epoch was coming to a close. This painting by

Stephan Lochner (239) already falls into the fifth

post-Atlantean time. I have shown you images in consecutive

order between the boundaries of the fourth and fifth

post-Atlantean time.

What are the particular characteristics? Don't we see

particular characteristics playing into representations in the

5th post-Atlantean time? Don't we see in the

lowering gaze of Mary, the blessing little hand of the child,

the differences in the right and left figures' expression, in

the individual depiction of the additional figures — do we not

see the characteristics of the 5th post-Atlantean

time — how the character's act in the pictorial representation?

Do we not see how the impact of personality arrives? Above all,

don't we already here see the desire to express the element of

the 5th post-Atlantean time within the imagery, the

most important element for Central Europe: light-and-dark or

chiaroscuro? — How little meaning the distribution of light and

dark had in the old tradition! People lived in light and

shadows but were not observing it, yet were feeling it -

because they experienced light bringing joy, sensing life in

light while darkness sank into rest, in darkness they withdrew

into mysterious soul depths. This inner living in the world in

the souls of single individuals which particularly comes to the

fore in the 5th post-Atlantean time, as well as the

application of chiaroscuro, indicate a distribution of light

masses: in the middle the light is above the Child, we see this

light dividing itself right and left in single masses, becoming

lighter upwards, no longer completed as in earlier version only

in a golden ground, but in a brightness. Thus the encroachment

of individual characters is what we see here; nobody can

actually look at these consecutive elements which I have

demonstrated to you, without becoming aware that something,

albeit quietly, but something new was coming into the

5th post-Atlantean time while the 4th

post-Atlantean epoch faded.

Let

us look once more at the previous Madonna:

243 238 Cologne Master: Madonna with the Wicken

flower — central section.

244

239 Stephan Lochner: Adoration of the kings, section:

Madonna

Memorise this child's face well and try to feel how much

tradition still lives in it. Now consider once again another

one:

241

Stephan Lochner: Madonna with the Violet flower (Cologne,

Diocesan Museum)

Look at the Madonna and the Child and note how a really new

impulse has entered just like a new impulse does enter with

each individual. Considering the following paintings of Stephan

Lochner. I want to stress that Stephan Lochner originated from

a region where most people were incapable of absorbing

tradition because most of them had the impulse to develop

individualism. It is the region around the Bodensee in the

region of Bavaria, the area of western Austria. Here the tribes

strived out of their folk nature towards individualism, mostly

rejecting tradition. Stephan Lochner was lucky, one might say,

to aim for the Bavarian anticipation of individual expression,

where, despite the striving for the individual, there still

lived the great sublime sacred tradition of olden times. As a

result, his individual impulse, much more pronounced than

Master Wilhelm with his radical individual urge, he connected

to his revolutionary individuation impulse with the smooth,

typically Cologne imaging tradition to produce this image.

For

an artist like Stephan Lochner depicting space within art had

not yet been invented; to depict space could simply not be done

at that time in Cologne, but his soul tried to introduce this

into the images.

Fully within the historical events, completely within

development this can be ascertained by a comparison between the

Virgin Mary image of the West compared to that of the East:

245

Russian Icon: the Mother of God by Vladimir (Moscow, Historical

Museum.)

Look at the next image:

242

Stephan Lochner: Madonna in the rose arbour (Cologne,

Wallraf-Richartz-Museum)

... which you also know already; look at it particularly in the

way the specific fits into the general, so typical in Stephan

Lochner's work, how the dark and light come to the fore even if

there is no continual intention of capturing space, to indicate

perspective, but in the chiaroscuro we see another kind of

spatial capture than that of perspective. The perspective is

more to the South, one could say: invented by Brunellesco — I

have explained this to you in previous years.

And

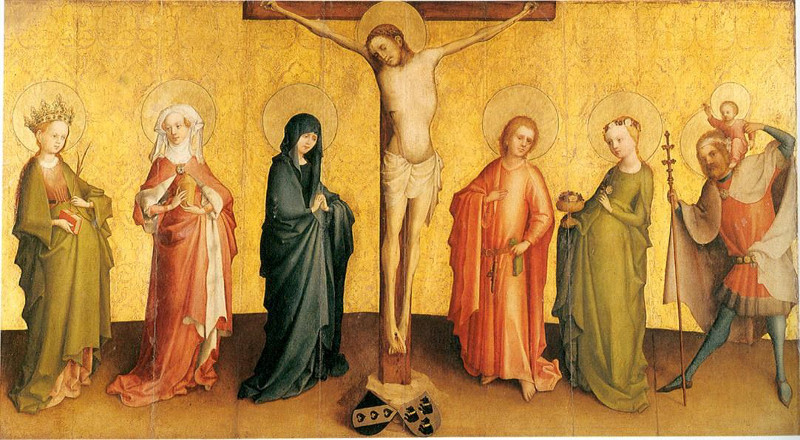

now …

240

Stephan Lochner: Christ on the Cross (Nurnberg, Germanic

Museum)

...

in which you see there is no trace yet of composition and how

here also, where the depiction would have insisted on a study

of space, there is nothing about space, and how on the other

side an attempt is made to depict each of the six accompanying

figures as individuals, with an attempt to individualise the

Redeemer Himself. Please recall the paintings of the Cologne

Masters (237, 238) and compare these with the paintings of

Stephan Lochner (239-242) which we have seen. It can't be

overlooked how deeply this incision imprints on us what lies

between the two: because this incision lies between the

4th and 5th post-Atlantean epochs.

Stephan Lochner attempted to depict soul qualities, but he

looked for representation in nature to find forms which express

the soul. Master Wilhelm still hovered in a supersensible

experience of the soul and his impressions came out of his

inner feelings. He didn't depict them by looking at a model.

Here (237) we still see a reference to the model in order for

the soul itself to identify with it. Master Wilhelm still

expresses his own feelings. Stephan Lochner is already a copier

of nature. This is in fact realism: realism rising. We can

clearly draw the boundaries between these two so divergent

painters, during hardly decades.

So

you see how the laws which we search for in spiritual science

really come to expression in single spheres of life when these

spheres are not taken as unimportant, but with their importance

are led before the soul.

Now

I would like to place this fact once again before your souls,

by introducing two painters who worked more in the South. This

took place in Cologne. Let us look more towards the South, to

Bavaria, Ulm or the Rhine area and we will see the how

conditions appear before and after the incision of the

5th into the 4th post-Atlantean epoch. I

want to present two paintings to you by Lukas Moser, who lived

in the beginning of the 15th Century, who can

certainly be counted as being from the 4th

post-Atlantean time.

Look at these paintings:

335

Lukas Moser: Ocean voyage of the Saints (from the

Magdalene-Altar, Tiefenbronn Church)

Try

to sense how everything painted in it is done in such a way

that one notices how the painter went through schooling which

insisted: when you place figures beside one another you must

place the one facing you, the other in profile; when you paint

waves, you must paint them like this.

Thus you see the entire play of the sea's waves, not as they

are observed, but “according to the rules”; you see

the figures as prescribed “according to the rules”;

nothing observed, everything composed. This image from the

Tiefenbronn altar thus depicts the ocean voyage of the

saints.

The

following image shows the time of repose, the night time rest

of the same saints:

336

Lukas Moser: Night's rest of the saints. (The Magdalene Altar,

Tiefenbronn Church)

...

A medieval house built on to a church, strongly suggestive that

nothing was observed but everything was painted out of the

head. Look at the sleeping Saint Zedonius: he still wears the

mitre as well as his gloves. It had to be painted according to

the rules where the main interest is located. Consider this as

an ongoing journey, because the saints are taking a trip, they

sail on the sea, they rest at night, it tells a story. Yet it

is presented as set out in an existed image remaining within

tradition. Lazarus resting in the bosom of this mother!

We

can look back to representations of earlier times when we have

such an image in front of us. This is at the point where the

4th post-Atlantean time came to a close. In the West

there were still prescriptions regarding how church imagery

should be painted. Painting was done according to particular

traditional rules. The painters obtained their method out of

tradition: this is what the Saint Zedonius looked like, what

Saint Lazarus looked like, Saint Magdalene and so on; they had

to be painted according to prescriptions, not quite as strictly

as in the East, but still according to the laws. However, he

still had to depict desires, instincts and reveal a story! In

this way the elements swim in and around and battle with the

end of the epoch.

Let

us also look back to the 13th, 12th and

11th centuries. In all the churches strict rules

were set. Each picture had to look the same as another right

through the whole of Christendom, only with a slight variation

in the way the things were ordered. If Saint Zedonius was

ordered, then he was to be painted according to prescription -

that was the tradition.

Let

us now think of the incision of the beginning of the

15th Century and go from Lukas Moser, the last

latecomer of the 4th post-Atlantean epoch, over to

Hans Multscher and see how these painters really already stood

in the beginning of the initial blossoming of the

5th post-Atlantean epoch. Look at these

paintings:

339

Hans Multscher: Birth of Christ (Berlin, German Museum)

...

and you observe how in these paintings the individual-personal

appear, characterising the personality. Moser does not have any

desire to look at nature. Here, (399) you find an artist who

strives to work out of the soul — yet who does not have the

slightest inkling of spatial treatment and above all mixes up

multi-coloured things in relation to space and perspective -

yet who strives to characterise it out of the soul, in such a

manner as if nature itself is characterised in the soul. He

already tries to depict individual figures.

340

Hans Multscher: Christ on the Mount of Olives (Vipiteno

Sterzing, Pallazo Municipale)

It

will become even clearer for you, what I've just been speaking

about, particularly when you look at the three sleeping figures

below. There is already an attempt, first of all, to express

the soul element, but there is also an attempt to depict the

nature of those sleeping. Compare this with what you can

remember about the sleeping saints on their sea voyage (335)

the resting time (336) and then you will realise what a mighty

incision lies between these developments. See how the

light-dark depiction is consciously brought in. Solely

characterized this way and not by working with perspective does

the painter reveal spatial relationships. Perspective is in

fact incorrect because an actual cohesive vanishing point can't

be found in any area of the painting; nowhere can a central

point be found from where the layout is arranged; yet still a

spatial relationship of a certain beauty exists through the

chiaroscuro.

341

Hans Multscher: Burial

Look at this “burial” scene. You find everything,

even in the depiction of the landscape itself, as characterised

by the individual's penetration of tradition: interest in

events without any indication coming out of the spiritual

world.

342

Hans Multscher: Resurrection.

You

see here how particular individualizing elements enter the

entire painting, an attempt is made in a corresponding manner

to represent the guardians, the twist of their bodies enhancing

the individualisation. I ask you to look up, to the left, how

an attempt was made to represent the figure's particular

situation, his unique experience, portraying his peculiar

individual inattentiveness. Try and imagine how the painter

tried to show the front view of the head, how on the right he

characterises the skull of the other guardian, from behind. One

can see how the attempt is made to show individual forms and

also how the chiaroscuro comes in. One can see how through

individualising, depiction of spatial element enters while

perspective is not at all yet clear. You can imagine the point

from which the individual lines go from the characters, but now

you need to think apparently quite far towards the front, where

the coffin is placed and you have to think again about another

reference point — regarding the trees! These are painted in

full frontal positions.

I

wanted to show you how the legitimate developmental impulses I

spoke about already last time in the Italian paintings have a

profound effect and what rises as characteristic in our time,

originating from the 15th Century, can only now be

understood if you clearly take the entire, deep meaning of

every time period, from the beginning of the 15th

Century, which built the boundary between the 4th

and the 5th post-Atlantean epochs.

What transformed itself here had already been living in all the

events and becoming of Europe, but it was pushed back from the

9th Century because Europe was made incapable at

that time; Europe first had to allow something else to take

form out of the depths of its being. Those in the East waited

in the meantime. We should promote an awareness today for what

waited there and what wanted to rise to the surface in the East

because these forces are available, these forces weave into

present day events, still wanting to be active. A clear

understanding of what pulsates through the world, what works in

the world, we need to take possession of, this which is an

urgent requirement for the present time epoch. This I am now

and have repeatedly stressed in the past. Through the

development of the middle age art in its characteristic time

period I wanted to make this clear for you. You see, here we

approach two incisive waves in history: one swell is everything

which came easterly from the south, the other is, I would like

to call it, coming from the depths itself. In these centuries -

13th, 14th and 15th, in the

centuries of freedom in cities, what wanted to rise from soul

depths to the surface was most strongly applicable. Then again

from the 16th Century another setback came -

development rose and fell, oscillated — and then, obviously not

simultaneously, the continuation of what had been started in of

the 15th Century became outwardly visible as I've

indicated to you, on the one side living in van Eyck, on the

other side Dürer, Holbein and so on.

We

see in the lower lands, towards Burgundy on the one side and

Nürnberg on the other, Augsburg, Basel, the results of

what wanted to come as a wave rising from soul depths to

introduce the 5th post-Atlantean period.

I

wanted to introduce only one of the impulses of this

5th post-Atlantean epoch to you. About other

impulses I have various opportunities to speak at the

moment.

|