|

The

Curative Education Course

by

Rudolf Steiner

Lecture One

Dornach, June 25, 1924

At

Rudolf Steiner's request no stenographer was present during

this course. The German text was assembled from notes taken by

several of the people present and can thus not be understood as

representing Dr. Steiner's exact words.

Translated by Mary Adams (revised and edited here to the extent

possible by Frank Thomas Smith)

My

dear Friends,

Well, as you know, we have quite a number of children whose

development has been arrested and whom we have now to educate

or in so far as it is possible, to heal. There are several of

these children here in the Clinic at Arlesheim, and there are

also a number at Lauenstein.

[The first two anthroposophical homes for handicapped children.]

In these lectures, I shall try to deal with our subject in such

a way that wherever possible our study leads to practical application.

Then, when Dr. Wegman puts some of the children at our disposal

for demonstration — for this is permissible among

ourselves — we shall also be able to discuss certain

cases with the child in front of us. To begin with, however, I

want to speak more in general terms about the nature of such

children.

It

is obvious that a thorough knowledge of education for healthy

children should already be possessed by one who wants to

educate incompletely developed children. For the very things we

notice in incompletely developed children, in children who are

suffering from some illness or abnormality, can also be

discerned in the so-called normal soul; only they show

themselves there less plainly, and in order to recognize them

we must be able to put to use a more intimate and close

observation. In some corner of soul of every human being lurks

a quality, or tendency, that would commonly be called abnormal.

It may be no more than a slight tendency to flights of thought,

or an incapacity to place words at the right intervals when

speaking, so that either the words fall over each other or else

the listener could go for a stroll between them.

Irregularities of this kind — and they are to be found

also in the will and feeling — can be noticed, at all

events to some slight degree, in the majority of human beings.

We shall have something to say about them later on, because for

anyone who sets out to deal, educationally or medically, with

serious irregularities, these slighter ones will be of

importance as symptoms. And one must, you know, be able to make

one's own careful study of symptoms, in the sense in which a

doctor speaks of symptoms by which he diagnoses illnesses. He

speaks also of the complex of symptoms which enables him to

survey the disease process; but he never confuses the complex

of symptoms with what is really the essential nature and

content of the disease itself. Similarly, in the case of an

incompletely developed child, we must regard what can be

observed in his soul simply as symptoms.

Psychography, as it is called — descriptive psychology

— is really nothing but symptomatology, the study and

knowledge of symptoms. When psychiatry today limits itself to

describing abnormal phenomena of thinking, feeling and willing,

this means no more than that it has made progress in the

accurate description of the complex of symptoms; and as long as

it cannot get beyond this point it is quite incapable of

penetrating to the essential nature of the illness. It is,

however, most important that we should be able to do this, to

perceive what “being ill” really means. And in this

connection, I want to ask your attention to the following. You

will find it helpful. Try to grasp it and hold it clearly

before your minds.

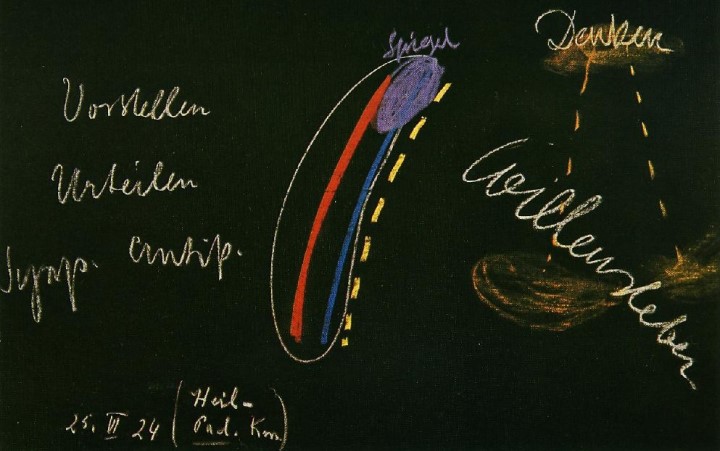

Suppose we have here

[A drawing was made.]

the physical body of

the human being, as it confronts us while the little child is

growing. Then we have the soul coming forth from this physical

body. This soul, which can show itself in varied expressions

and manifestations, may be normal or it may be abnormal. But

now the only possible grounds we can have for speaking of the

normality or abnormality of the child's soul, or indeed of the

soul of any human being, is that we have in mind something that

is normal in the sense of being average. There is no other

criterion than the one that is customary among people who abide

by ordinary conventions; such people have their ideas of what

is to be considered reasonable or clever, and then everything

that is not an expression of a “normal” soul (as

they understand it) is for them an abnormality. At present

there is really no other criterion. That is why the conclusions

people come to are so very confused. When they have in this way

ascertained the existence of “abnormality”, they

begin to do — heaven knows what! — believing they

are thereby helping to get rid of the abnormality, while all

the time they are driving out a fragment of genius! We shall

get nowhere at all by applying this kind of criterion, and the

first thing the doctor and teacher must do is to reject it and

get beyond the stage of making pronouncements as to what is

clever or reasonable, in accordance with the habits of thought

that prevail today. Particularly in this domain we must refrain

from jumping to conclusions and simply look at things as they

are. What have we actually before us in the human being?

Let

us look right away from this soul, which emerges only by

degrees and in which a part is often played by teachers —

concerning whom perhaps the less said the better! — let

us look away from this soul, and then we find, behind the

bodily nature, another soul, a spirit soul, which descends

between the time of conception and birth from the spiritual

worlds. For the first-mentioned soul is not the one which

descends from spiritual worlds. The soul which descends from

the spiritual worlds is something quite different and is not,

in the ordinary way, perceptible to earthly consciousness. This

soul that descends from the spiritual worlds takes possession

of the body which is being built up from the sequence of

generations in accordance with heredity. And if this soul is of

such a kind that it tends, when it grasps liver-substance, to

form a diseased liver, or if it finds in the physical and the

etheric bodies some inherited tendency to disease, which gives

rise to a feeling of illness, then disease will make its

appearance. Similarly, any other organ or nexus of organs may

be faultily inserted into what comes down from the world of

soul-and-spirit. When the connection has been made, when the

union has come about between what descends and what is

inherited, when this entity of soul-and-body has been formed,

then there arises — but even then, no more than as a

reflection in a mirror — that which we know ordinarily as

our soul life, as it manifests in thinking, feeling and

willing. This soul life that manifests in thinking, feeling and

willing is, however, as we said, no more than a reflection, it

is really just like a reflection in a mirror. It is all

obliterated when we fall asleep. The really permanent soul is

behind; it makes its descent and passes through repeated

earth-lives. And if we ask where it is in man, the answer is:

It has its seat in the organisation of the body. How is this to

be understood?

Let

us think first of the human being in his three systems: nervous

system, rhythmical system and metabolism-limb system. You will

understand me when I say that the nervous-and-sensory system is

located principally in the head; we can therefore speak —

although, of course, diagrammatically only — of the head

system when we are referring to the nervous-and-sensory system.

This is more literally correct in the case of the very young

child, where the upbuilding function of the nervous-and-sensory

system proceeds from the head and works thence into the whole

organism. The nerves-and-senses system, then, is localized in

the head. It is a synthetic system. What do I mean by that? It

brings together all the activities of the organism. In the head

is contained, in a sense, the whole human being. When we speak

of hepatic activity — and we ought really to speak always

of the activity of the liver, for what we see as liver is

nothing but a liver process that has become fixed — this

liver activity is entirely in the lower body; but for each such

nexus of functions there is a corresponding activity in the

head. Here, shall we say, is the liver activity. And there is a

correspondence to this liver activity in a particular activity

in the human head or brain. Here in the lower body, the liver

is relatively separated from the other organs, from kidneys,

stomach and so on. But in the brain, everything flows together,

the hepatic activity flows together with the other activities;

so that the head is the great synthesizer of everything that is

going on in the organism. And the effect of all this

synthesized activity is to set up a destructive process, a

process of breaking down. Substance falls away.

Whilst we have thus in the head a synthesizing process, in the

whole of the rest of the organism, and especially in the

metabolism-and-limbs system, we have an analysing process;

here, in contrast to the head, everything is kept separate.

Whereas in the head, the renal activity takes place together

with the intestinal activity, in the rest of the organism the

several activities are held apart. In the head, however,

everything flows together, it is all synthesized.

Now

this flowing together — accompanied as it is by a

continual falling away of substance, like rain — this

synthetical activity of the head is the basis of all our

thinking. For what has to happen in order that man can think?

What enters into man from the realm of soul and spirit,

enabling him to be active in the world — this

soul-and-spirit nature of his has to be endowed, in the region

of the head, with the synthesizing function and so be capable

of synthesizing in the right way the inherited substance; then

this harmoniously synthesized hereditary substance can become a

mirror. When, with the descent of soul and spirit, the

synthesizing activity begins to take place in the head, the

head becomes a mirror; the outer world is reflected in it, and

this produces the thinking that we ordinarily observe. We must

therefore distinguish between two functions of thinking: first

the one which acts behind the realm of the perceptible and

builds the brain — this is the permanent element in human

thinking; and then there is the thinking function that is not

real in itself but only a reflection. This latter function is

obliterated every time we fall asleep; it subsides as soon as

we stop thinking.

Another part of what descends from the realm of spirit and soul

builds up the system of metabolism and limbs —

analytically, building their organs which are separate one from

another and have each their own clearly distinguishable

outlines. If you set out to study the human body with its

several clearly distinguishable outlines, then in this body you

find liver, lungs, heart and so on. The metabolism-and-limbs

system is connected with all of these. The rhythmic system we

do not see; everything which is filled with physical substance

belongs to the system of limbs and metabolism; even what we can

see of the brain is metabolism. Now it is these single,

analytically built-up organs that lie at the basis of the will

in the human being, just as the synthesizing activity is the

basis of thinking.

And

now let us think of a human being who has arrived at being a

“grown-up”. During his earthly life he reached the

age of seven and got his second teeth, he grew to be fourteen

years old and attained puberty, finally he reached the age of

twenty-one, when the consolidation of his soul took place. If

we want to have any understanding at all of the development of

the child, we must clearly distinguish between the body a human

being has who has passed through the change of teeth, and the

body of a very young child who has not yet experienced the

change of teeth. As a matter of fact, what can be observed by

comparing these two outstanding examples is happening

continuously. The body changes with each year that passes. We

are perpetually thrusting something out from our body; a

streaming outwards, a centrifugal impulse is at work pushing

the body out. The consequence is that the human body is

completely renewed every seven or eight years. This renewal is,

however, particularly significant about the time of the change

of teeth at about the seventh year.

The

body which we have from birth till the change of teeth is, in a

sense, nothing else than a model that we take over from our

parents; it contains the forces of heredity, our forefathers

have helped to build it. In the course of the first seven years

we thrust off this body. And what have we then? A completely

new body comes into being; the body that man has after the

change of teeth is not built up by the forces of heredity, but

by the spirit-and-soul which has descended. The human being has

an inherited body until the change of teeth, and no longer; but

while he is thrusting off this body, he builds up a new body,

working from out of his own individuality. Thus, only since the

change of teeth have we had what we may call our own body. But

the inherited body is used as a model; and according as the

spirit-and-soul is strong or weak, will it either be in a

position to proceed in a more individual direction when

confronted with the inherited form, or be subject to the

inherited form — in which case the soul will be compelled

to shape the second body like the first, which was shaped by

the parents. What is usually adduced in the theory of heredity

is really nonsense. For it is assumed that the laws that

underlie man's growth up to the change of teeth simply continue

into later life; whereas the truth is, that the influence of

heredity has to be reckoned with only until the change of

teeth, and no further; the individuality then anters and builds

the second body.

We

must therefore distinguish, when speaking of a child, between

the body of heredity and the individual body which is its

successor. The individual body — and this body alone can

truthfully be called the personal body of the human being

— develops by degrees. Between the seventh and fourteenth

years the very strongest activity of which the individuality is

capable goes forward. Either the individuality conquers the

forces of heredity during this period, and then it can be

observed in the child that, after the change of teeth, he

begins to work his way out of the forces of heredity —

the fact will be clearly perceptible, and we teachers must take

note of it — or, the individuality is completely subject

to the forces of heredity, to what is contained in the model,

with the result that the hereditary likeness to the parents

simply continues beyond the seventh year. But it all depends,

you see, upon the individuality, not upon the forces of

heredity. Suppose I am an artist and you give me something to

copy and I change it considerably. Just as little as I can say

that you are responsible for my picture, just so little can it

be said that a person has acquired through heredity the body he

bears from the seventh year onward. This truth we must master

thoroughly, and then be able to know for ourselves in any

particular case how strongly the individuality is working.

Between the seventh and fourteenth years every human being

experiences a process of growth and development which

expresses, as strongly as in his case is possible, the

individuality he has brought down with him. In this period of

his life the child is thus comparatively shut off from the

external world; and we teachers have an opportunity to watch

during these years the wonderful unfolding of the forces of the

individuality. But if this development were to continue after

the fourteenth year, if the human being were to go on into

later life with nothing further than this unfolding of

individuality, he would become a person who perpetually refuses

and rejects everything that approaches him, a person utterly

without interest in the world around him. That this does not

happen is due to the fact that, during the aforesaid period, he

is building his third body, which manifests at puberty, and

this third body is built up to accord with the forces in the

earthly environment. The relation of the sexes is not

everything; the exaggerated importance given to it is just a

consequence of our materialistic turn of mind. In reality, all

connections with the outer world which begin to make their

appearance at puberty are fundamentally of the same nature. We

should really speak, therefore, not of sexual, but of earthly

maturity. And under earthly maturity we have to include the

maturity of the senses, the maturity of breathing — and

another such sub-division is also be sexual maturity. This

gives the true picture of the situation. The human being, then,

reaches earthly maturity. He begins to absorb what is outside

and foreign to him; he acquires the faculty of being sensitive

and not indifferent to his environment. Before this time, he is

not susceptible to the other sex, neither is he susceptible to

his environment. Thus, does the human being form and develop a

third body, which is active in him until the beginning of the

twenties.

What descends from the spiritual world reaches a kind of end at

the time of the change of teeth; but it continues to work until

the twentieth year. It has already taken form in the organs and

has given the human being individual maturity, and earthly

maturity. Suppose that now some abnormality shows itself in the

soul, which reflects — and is in conformity with —

the structure of the organs and is conditioned by the

development of the human being. We shall then have an

abnormality of soul that has come about in this way. But if,

after the human being has passed his twenty-first year, an

abnormality appears in the liver or in some other organ, this

organ is by then so much on its own and so detached, that the

will — in its inner aspect — can keep itself

independent of it. This is less and less possible the further

one goes back into the years of childhood. But in a grown

person the soul has become relatively independent; the organs

already have a definite direction, and the oncoming of illness

in an organ will not work so strongly upon the soul and can

therefore be treated simply as a disease in that organ. In the

very young child, however, everything is still working

together; a diseased organ still works into the life of soul

— and very actively.

The

diseases usually diagnosed by our modern pathology are the

cruder illnesses; the subtler illnesses are not really

accessible to histology. These lie in the fluids that permeate

an organ, such as the liver for instance, or even in the air

— through that organ. The warmth permeating the organ is

also of quite special significance for the soul. If therefore

we are dealing with a child who shows evidence of a defect in

the will, the first thing we must do is to ask ourselves: with

what organ is the defect in the will connected? Is there some

organ showing signs of degeneration or of illness, with which

we can connect the defect in the will? That is the really

important question.

A

defect in thinking is not of such great importance. Most

defects are really defects in the will; for even when you find

a defect in thinking, you must look carefully to see to what

extent this defect in thinking is really a defect in will. When

someone thinks too rapidly or too slowly the thoughts

themselves may be quite correct; the trouble is that the will

which works in the dove-tailing of the thoughts into each other

is faulty. We must be able to discover in all such cases to

what extent the will is a factor. One can really only be sure

that there is a defect in thinking when, independently of the

will, deformations of thought, sensory delusions, make their

appearance. These then arise quite unconsciously in the human

being in the process of relating himself to the outer world.

The mental picture itself becomes irregular, or we have

something like “fixed ideas”, where the very fact

that they are fixed ideas lifts them out of the sphere of the

will. It is therefore most important we should take pains to

discern whether in a particular case we have to do with a

defect in the will or a defect in thinking. Defects in thinking

fall for the most part into the medical domain. In the

education of incompletely developed children, we have mainly to

do with defects of the will.

And

now look how the entire being of man plays into his

development. You can appreciate this from the description we

have been giving. Take the first seven years. There may be

defects due to heredity. It is during this period that such

defects come particularly into consideration. But a hereditary

defect should not be regarded in the mistaken way in which it

is regarded by modern science; it does not fall to our lot by

chance, but as a karmic necessity. Out of our own lack of

knowledge — in the spiritual world, of course — we

have chosen a defective body, one that is defective as the

result of the generations. The existence of defective forces of

heredity means that before conception there was a lack of

knowledge of the human organism. Before a human being comes

down to Earth, he must have an exact knowledge of the human

organism; otherwise he cannot enter into this organism in the

right way during the first seven years, neither can he

transform it rightly. The knowledge about the inner

organisation of man which we acquire between death and a new

birth is infinite in comparison with the scraps of knowledge

that have been acquired by external observation and are to be

found in the physiology or histology of today. The knowledge

which we have between death and a new birth and which then

sinks down into the body, and is forgotten because it sinks

down, a knowledge that does not direct itself, with the help of

the senses, to the outer world — this knowledge is

immeasurably great; it is however impaired if, in an earlier

life, we neglected to develop interest in our surroundings or

were prevented from doing so.

Suppose one day a civilisation were to arise that confined

human beings in rooms, keeping them there from morning till

evening, so that they were debarred from taking any interest at

all in the outer world. What would be the result? These human

beings would of course by such a process be precluded from

acquiring any knowledge of the outer world; and this would mean

that when they passed afterwards through death and in the

spiritual world they would be insufficiently equipped for

getting to know the human organism in this spiritual world,

with the result that when they descend again to Earth, they

would come with far less knowledge than one who had in his

previous life acquired the faculty for looking out upon his

surroundings with free, open perception.

There is another secret connected with this. You go through the

world. You think perhaps, as you go through the world, that a

single day is of little importance. And so, it is for ordinary

consciousness, but not for that which is building the

unconscious within this ordinary consciousness. If for one

single day, as you go through the world, you observe the world

intently and carefully, then this gives you the preliminary

condition for knowledge of all that is contained in the human

body. For what is the outer world in earthly life is the

spiritual inner world in life beyond the earth. And we shall

have to speak further of the results that cannot but ensue from

our present civilisation, and of how it comes about that

children are born defective. Those human beings who live shut

off from the world today will all of them at some time or other

descend with a lack of knowledge of the human organism, and

they will choose ancestors who would otherwise have remained

barren. It will be precisely those parents who tend to beget

sick or feeble bodies who will be chosen, while those who would

be capable of producing good bodies will remain sterile. Yes,

it is actually so: it depends upon the whole development of a

particular epoch, how a generation, when it descends again to

birth, will be formed and built.

When we look at a young child, we must see what it is in this

child that has come from its previous earthly life. We must

understand why it chooses organs that are diseased due to the

forces of heredity; and again, why he works himself into this

body with an incompletely developed individuality. Think of the

many possibilities that exist for a child, in this first period

up to the change of teeth, owing to the fact that what has come

down is not always quite able to cope with what it finds before

it. There is the possibility, let us say, of the child having a

good model in respect to the development of the liver; but

because the individuality is incapable of understanding what is

contained in the liver, the development of the same (upon the

model provided) during the second life-period is incomplete,

and we have, in consequence, a very significant defect of will.

Precisely in a case where the development of the liver has not

been complete in this second period, has not been in accordance

with the good development of the model, we find a defect of the

will. The child has will but does not get to the point of

carrying it out; the will remains in the thinking. As soon as

the child has begun to do something, he wills something else.

The will gets stuck, it is transfixed. For you must know that

the liver is not merely the organ modern physiology describes;

it is the organ that gives the human being the courage to

transform a deed which has been thought of into an accomplished

deed.

Imagine a man who sees a tram about to start and knows that he

has to go to Basel, but at the last minute cannot get into the

tram. There are people like this. Something holds him back, he

does not reach the point of getting in. This kind of paralysis

of the will may sometimes reveal itself in most curious ways.

But wherever it occurs, there is invariably a subtle defect of

the liver. The liver is the mediator which enables an idea that

has been resolved upon to be transformed into an action carried

out by the limbs. In point of fact, every organ is there in the

body for the purpose of acting as mediator for something to

come about.

I

was once told about a certain young man who had an illness of

this kind. He would be waiting for a tram, but when the tram

came he would suddenly stop short and not get in. Nobody knew

why, he did not know himself. He simply stood there rooted to

the spot. What was the cause of this condition? It was a very

complicated affair. The young man's father was a philosopher.

He had divided the faculties of the soul in a rather singular

manner into ideas, judgments and the forces of sympathy and

antipathy. He did not reckon the will among the attributes of

the soul. The will was omitted in his enumeration — from

sheer desire on his part to be honest and not to put forward

more than revealed itself clearly to his consciousness. He

carried this to such a point that it became perfectly natural

to him to have no mental concept of the will at all. Then at a

comparatively advanced age he had a son. By perpetually

ignoring the will he, the father, had implanted into the liver

an inclination not to transform subjective intentions into

deeds. This evolved in the son as an illness. And now you can

see why the individuality of the son chose this man for his

father. The individuality of the son had no understanding of

how to cope with the inner organisation of the liver; so, he

chose a constitution in which he need not trouble himself about

the liver, a constitution in which the liver was lacking in the

very function he had himself failed to bring down. You have

here a very striking instance of the need to look also into

karma if we want to understand the child.

This is what I wanted to say to begin with, and tomorrow at the

same hour we will continue.

| |

Lecture 1,

Blackboard Image 1

Click image for large view | |

|