|

III

The

Formation of the Human Ear

Eagle,

Lion, Bull and Man

A

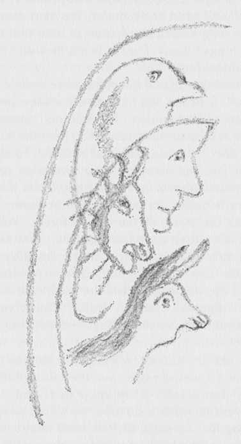

question was asked about the design that appeared on the cover

of the Austrian journal, Anthroposophy, showing the

heads of an eagle, a lion, a bull and a man.

Dr.

Steiner. Gentlemen, I think we should first bring to a

conclusion our explanation of the human being, and then

next time consider the aspects of man that these four symbols

— the eagle, lion, bull and man — represent. Before

we can say anything about them we must build a foundation, and

this is something I shall try to do before the end of today's

lecture. These four creatures, including man, spring from an

ancient knowledge of the human being. They cannot be explained

as the ancient Egyptians, for instance, would have done, but

today they must be explained differently. One can interpret

them correctly, of course, but nowadays one must begin from

slightly different suppositions.

I

would like now to direct your attention again to the way the

human being evolves from his embryonic stage. I would like you

to look once more at the very first stage, the earliest period.

Conception has occurred, and the embryo is developing in

the mother's womb. At first, it is just one microscopic cell

containing proteinaceous substance and a nucleus. This single

cell, the fertilized egg, actually marks the beginning of

man's physical life.

Let us

look then at the processes that immediately follow. What does

this tiny egg, placed within the body of the mother, do? It

divides. The one cell becomes two, and each of these cells

divides in turn, thus creating more and more cells like the

first. Eventually, our whole body is made up of such cells.

They do not remain completely round but assume all manner of

shapes and forms.

We

must now take into account something I have mentioned

before, which is the fact that the whole universe acts upon

this minute cell in the mother's body. Nowadays, of course,

such matters generally cannot be met with the necessary

understanding, but it is nonetheless true that the whole cosmos

works upon this cell. It is not at all the same if the ovum

divides when, say, the moon stands in front of, or at a

distance from, the sun. The whole starry heavens shed an

influence on this cell, whose interior forms itself

accordingly.

I have

said before that during the first few months only the head of

the unborn child is developed. (Referring to a drawing.) The

head is already formed to this extent, and the rest of the body

is really only an appendage. There are tiny little stubs, the

hands, and other small protrusions, the legs. As it develops,

the human being will transform its little appendages into

hands, arms and feet.

How

does this come about? How does it occur? The reason lies in the

fact that in the earlier embryonic stages the influence

of the starry heavens is greater. As the embryo develops and

grows during those months in the mother's womb, it becomes

increasingly subject to the gravity of the earth. When the

world of the stars acts upon man, the emphasis is always on the

head. It is gravity that, in time, draws out the other parts.

The farther back we go, examining the second or first months of

pregnancy, the more do we find these cells exposed to the

influence of the stars. As more and more cells appear and

millions gradually develop, they become increasingly

subject to the forces of the earth.

Here

is convincing evidence that the human body is magnificently

organized. I would like to make this evident by considering one

of the sense organs. I could just as easily take the example of

the eye, but today I shall speak about the ear. You see, one of

these cells develops into the ear. The ear is set into one of

the cavities of the skull bones, and if you examine it

properly, you will find that it is quite a remarkable

structure. I shall explain the ear so that you can get some

idea of it. You will see how such a cell moulds itself

while it is still partially under the influence of the stars

and partially under the influence of the earth. The ear is

formed in such a marvellous way so that man can actually

make use of it.

Let us

proceed from the outside inward. To begin with, each of you can

take hold of your auricle, the outer ear. We have sketched it

as seen from the side (1). It consists of gristle and is

covered with skin. It is designed to receive the maximum amount

of sound. If we had only a hole there, the ear would capture

much less sound. You can feel the passage into your ear; it

goes into the interior of the so-called tympanic cavity, the

interior of the head's bony system. This passage or canal is

closed off inside by the eardrum, the tympanic membrane. There

is really a thin, delicate, tiny skin attached to this canal,

which might be likened to that of a drumhead. The ear, then, is

closed off on the inside by the eardrum (2).

I'll

continue by drawing the cavity that one observes in a skeleton

(3). Here are the skull bones; here are the bones going

to the jaw. Inside is a cavity into which this canal leads that

is closed off by the eardrum. Behind the outer ear, the

auricle, you have a hollow space, which I shall now tell you

about. Not only does this canal, this outer passage that you

can put your little finger into, lead into the head cavity, but

another canal also leads into this cavity from the mouth. In

other words, two passages lead into this cavity: one from the

exterior that extends inward to the eardrum, and one from the

mouth that enters behind the eardrum, which is called the

Eustachian tube, though the name does not matter.

Now we

come to a strange-looking thing — a veritable snail

shell, the cochlea. It consists of two parts. Here is a

membrane, and here is a space, the vestibule. Over here is

another space, the tympanic cavity. The whole thing is filled

with fluid, a living fluid, which I have described to you in

another lecture. So within all this fluid is something made of

skin that looks like a snail shell. Inside this snail shell,

called the cochlea, are myriad little fibres that make up the

basilar membrane. This is quite interesting. If you could

penetrate the eardrum and look beyond it, you would find this

soft snail shell, which is covered on the inside with minute,

protruding hair-like fringes.

What,

actually, is inside the cochlea? When one approaches the

question truly scientifically, one notices that this is really

a small piece of intestine that has somehow been placed within

the ear. Just as we have the intestines within our abdomen, so

do we have a tiny piece of intestine-like skin within our ear.

The ear's configuration, then, is such that it contains a

little intestine, just as in another part of the body we have a

larger intestine. The cochlear duct, which is surrounded by a

living fluid called the endolymph, is filled with another

called the perilymph. All this is extremely interesting. The

cochlea is closed off here by a tiny membrane shaped like an

oval window, and here, again, by another little membrane that

looks like a round window. Just as we can beat on a drum and

make it vibrate, so do the sound waves, coming in from both

sides, set into motion this little membrane, the oval

window.

The

oval window is a membrane set in the middle of the cochlea, and

it closes off the inside of the little snail shell, which is

filled with the slightly thicker fluid, the perilymph. The

fluid on the outside is thinner. Below the oval window is

another little membrane called the round window. Here we now

approach something marvellous. Two tiny delicate bones sit on

the membrane of the oval window. They look like a stirrup and

are called the stapes. People also refer to them as the

stirrup. So the stirrup sits on the little membrane,

protruding in such a way as to resemble an upper and a

lower arm on the membrane. Picture such an upper and lower arm

of the stirrup and then here, strangely enough, another

independent bone, the incus or anvil. The first two bones

of the stirrup are connected by a joint; the incus is

independent. These tiny bones are all in the ear, and since

materialistic science looks at everything superficially, it

calls the bone that sits directly on the eardrum, the hammer,

this other bit of bone in the middle, the anvil, and this

other, the stirrup — or malleus, incus and stapes.

Ordinary science, however, doesn't really know what these bones

are. What is found here in the two arms of the stirrup is only

a little different from an arm bent at the elbow. See, an elbow

joint is the same as this joint of the stirrup above the

membrane. And there is a kind of hand, on which sits an

independent bone. We don't have such a bone in our hand, but it

is comparable to our kneecap. So we can rightfully say that

this is also like a leg, a foot; then that would be the thigh,

that the knee (sketching), there the foot stands on the

membrane, and there is the kneecap.

You

see, it is most interesting that in the cavity of the ear we

have first a kind of intestine and then a real hand, arm or

foot. What is the purpose of all this? Well, imagine that a

sound strikes the eardrum and everything in there begins to

vibrate. Without being aware of it, the person is determining

within the ear what kind of vibration it is. Now think of this,

which you may have experienced at some time. You are standing

somewhere on a street when something explodes behind you. You

feel the explosion inwardly and may feel sick to your stomach

from the shock. But this delicate shock that vibrates through

the cochlea's “intestine” is felt by the fluid

within, which conveys the vibrations that are imparted by the

“touching” of the eardrum with a

“hand,” as it were.

Now I

would like to point out something else to you. What is the

purpose of this Eustachian tube leading from the mouth to the

inner ear? If sounds simply passed into the ear from the

auricle, we would not need it, but to comprehend another's

speech we must first have learned to speak ourselves.

When we listen to someone else and wish to comprehend

him, the sounds we have learned to speak pass through the

Eustachian tube. When another person is speaking to us, the

sounds come in through the auricle and make the fluid vibrate.

Because the air passes into the ear from the outside, and since

we know how to set this air in motion with our own speech, we

can understand the other person. In the ear, the element of our

own speech that we are accustomed to meets the element of what

the other person says; there the two meet.

You

see, when I say, “house,” I am accustomed to

having certain vibrations occur in my Eustachian tube;

when I say, “powder,” I experience other

vibrations. I am familiar with these vibrations. When I hear

the word “house,” the vibration comes from outside,

and because I am used to identifying this vibration when I say

the word myself, and since my comprehension and the vibration

from outside encounter each other in the ear, I am able

to recognize its meaning. The tube that leads from the mouth

into the ear was there when as a child I learned to speak.

Thus, we learned to understand the other person simultaneously

as we learned to talk. These matters are most interesting.

Now,

things are really like this. Imagine that nothing but what I

have just sketched here existed in the ear. Then you could at

least understand another person's words and also listen to a

piece of music, but you would not be able to remember what you

had heard. You would have no memory for speech and sound if the

ear had nothing more than these parts. There is another amazing

structure in the ear that enables you to retain what you

have heard. These are three hollow arches, which look like this

(sketching). The second is vertical to the first, and the

third, vertical to the second. Thus, they are vertical to each

other in three dimensions. These so-called semi-circular canals

are hollow and are also filled with a living, delicate fluid.

The remarkable thing about it is that infinitely small crystals

are constantly forming from it. If you hear the word,

“house,” for example, or the tone C, tiny crystals

are formed in there as a result. If you hear a different word

— “man,” for instance — slightly

different crystals are formed. In these three little

canals, microscopically small crystals take shape, and

these minute crystals enable us not only to understand

but also to retain in our memory what we have comprehended. For

what does the human being do unconsciously?

Imagine that you have heard someone say, “Five

francs.” You want to remember what has been said, so with

a pencil you write it into your notebook. What you have written

with lead in your notebook has nothing to do with live francs

except as a means of remembering them. Likewise, what one

hears is inscribed into these delicate canals with the minute

crystals that do, in fact, resemble letters, and a subconscious

intelligence in us reads them whenever we need to recall

something. So, indeed, we can say that the memory for tone and

sound is located within these three semi-circular canals. Here

where this arm is located is comprehension, intelligence. Here,

within the cochlea is a portion of man's feeling. We feel the

sounds in this part of the labyrinth, in the fluid within the

little snail shell; there we feel the sounds. When we speak and

produce the sounds ourselves, our will passes through the

Eustachian tube. The whole configuration of the human soul is

contained in the ear. In the Eustachian tube lives the will;

here in the cochlea is feeling; intelligence is in the auditory

ossicles, those little bones that look like an arm or leg;

memory resides in the semi-circular canals. So that man can

become aware of the complete process, a nerve passes from here

(drawing) through this cavity and spreads out everywhere,

penetrates everywhere. Through this auditory nerve, all

these processes are brought to consciousness in our brain.

You

see, gentlemen, this is something quite remarkable. Here in our

skull we have a cavity. One enters the inner ear cavity by

passing from the auricle through the auditory canal and

eardrum. Everything I have described to you is contained

therein. First, we stretch out the “hand” and touch

the incoming tones to comprehend them. Then we transfer

this sensation to the living fluid of the cochlea, where we

feel the tone. We penetrate the Eustachian tube with our will,

and because of the tiny crystal letters formed in the

semi-circular canals, we can recall what has been said or sung,

or whatever else has come to us as sound.

So we

can say that within the ear we bear something like a little

human being, because this little being has will,

comprehension, feeling and memory. In this small cavity

we carry a tiny man around with us. We really consist of many

such minute human beings. The large human being is actually the

sum of many little human beings. Later, I'll show you that the

eye is also such a miniature man. The nose, too, is a little

human being. All these “little men” that make up

the total human being are held together by the nervous

system.

These

miniature men are created while man is still an embryo in the

mother's body. All that is being formed and developed there is

still under the influence of the stars. After all, these

marvellous configurations — the canals that produce the

crystals, the little auditory bones — cannot be moulded

by the gravity and forces of the earth. They are organized in

the womb of the mother by forces that descend from the stars.

The cochlea and Eustachian tube are parts that belong to man as

a being of earth and are developed later. They are shaped by

the forces that originate from the earth, from the gravity that

gives us our form and that enables the child to stand upright

long after it is born.

You

see, if initially one knows how the whole human being

originates from one small cell, and how one cell is

transformed into an eye while another becomes an ear and

a third the nose, one understands how man is gradually built

up. Actually, there are ten groups of cells that transform

themselves, not just one, but we may still imagine there

to be one cell in the beginning. So, at first, just one cell

exists. This produces a second, which by being placed in a

slightly different position comes under a different

influence and develops into the ear. Another develops into the

nose, a third into the eye, and so on. None of this proceeds

from any influence of the earth. The forces of the earth can

mould only those parts that are mostly round, just as in the

abdomen the earth organizes the intestinal system.

Everything else is formed by the influence of the stars.

We

know of these matters today because we have microscopes.

After all, the auditory bones are minute. Remarkably

enough, these things were also known by men in ancient times,

though the source of their knowledge was completely different

from that of today. For example, 3,000 years ago the ancient

Egyptians were also occupied with a knowledge of man's

organization and knew in their way just how remarkable the

inner functions of the human ear are. They said to themselves

that man has ears, eyes and other organs belonging to the head.

If we wish to explain them, we must ask how the ear, for

instance, was moulded so differently from the other organs. The

ancients said that those organs that are part of the head

developed primarily from what comes down to the earth from

above. They said, “High up in the air the eagle develops

and matures. One must look up into that region if one wishes to

observe the forces that form the organs in the human

head.” So, these ancient people drew an eagle in place of

the head when they were depicting the human being.

When

we observe the heart or lungs, we find that they look

completely different from the ear or eye. When we look at the

lungs, we cannot turn to the stars, nor can we do so in the

case of the heart. The force of the stars works strongly in the

heart, but we cannot deduce the heart's configuration solely

from the stars. The ancient Egyptians knew this; they knew that

these organs could not be as closely linked to the stars as

those of the head. They pondered these aspects and asked

themselves which animal's constitution emphasized the organs

similar to the human heart and lungs. The eagle particularly

develops those organs that man has in his head.

The

ancients thought that the animal that primarily develops the

heart, that is all heart and therefore the most courageous, is

the lion. So they named the section of man that contains the

heart and lungs “lion.” For the head, they said

“eagle,” and for the midsection,

“lion.”

They

realized that man's intestines were again organs of a different

kind. You see, the lion has quite short intestines; their

development is curtailed. The minute “intestine” in

the human ear is formed most delicately, but man's

abdominal intestines are by no means shaped so finely. In

observing the intestines, you can compare their formation only

with the nature of those animals that are mainly under their

influence. The lion is under the influence of the heart,

and the eagle is under the sway of the upper forces. When you

observe cows after they have been grazing, you can sense how

they and their kind are completely governed by their

intestines. When they are digesting, they experience

great well-being, so the ancients called the section of man

that constitutes the digestive system, “bull.” That

gives us the three members of human nature: Eagle — head;

lion — breast; bull — abdomen.

Of

course, the ancients knew when they studied the head that it

was not an actual eagle, nor the midsection a lion, nor the

lower part a bull. They knew that, and they said that if there

were no other influence, we would all go about with something

like an eagle for our head above, a lion in our chest region

and a bull down below; we would all walk around like that. But

something else comes into play that transforms what is above

and moulds it into a human head, and likewise with the other

parts. This agent is man himself; man combines these three

aspects.

It is

most remarkable how these ancient people expressed, in such

symbols, certain truths that we acknowledge again today. Of

course, they could form these images easier than we because,

though we modern people may learn many things, the thoughts we

normally acquire in school do not touch our hearts too deeply.

It was quite different in the case of these ancient people.

They were seized by the feeling emanating from thoughts and

therefore dreamed of them. These people dreamed true dreams.

The whole human being appeared as an image to them, and from

his forehead they saw an eagle looking out, from the heart, a

lion, and from the abdomen, a bull. They combined this into the

beautiful image of the whole human being. One can truly say

that long-ago people composed their concept of the human being

from the elements of man, bull, eagle and lion.

This

outlook continued in the description of the Gospels. One

frequently proceeded from this point of view. One said that in

the Gospel of Matthew the humanity of Jesus is truly described;

hence, its author was called “man.” Then take the

case of John, who depicts Jesus as if He hovered or flew over

the earth. John actually describes what happens in the region

of the head; he is the “eagle.” When one examines

the Gospel of Mark, one will find that he presents Jesus as a

fighter, the valiant one; hence, the “lion.” Mark

writes like one who represents primarily those organs of man

situated in the chest. How does Luke write? Luke is presented

as a physician, as a man whose main goal is therapeutic, and

the healing element can be recognized in his Gospel. Healing is

accomplished by bringing remedial forces into the digestive

organs. Consequently, Luke describes Jesus as the one who

brings a healing element into the lower nature of man. Luke,

then, is the “bull.” So one can picture the four

Gospels like this: Matthew — man; Mark — lion; Luke

— bull; John — eagle.

As for

the journal whose cover depicts the four figures that you asked

about, its purpose is to present something of value that can be

communicated from one human spirit to another. So the true

human being should be depicted in it. In rendering this

drawing, the eagle is represented above, then the lion and

bull, with man encompassing them all. This was done to show

that the journal represents a serious concern with man. This is

its aim. Not much of the human element is present in the bulk

of what newspapers print these days. Here attention was to be

drawn to the fact that this newspaper or journal could afford

man the opportunity to express himself fully. What he says must

not be stupid: the eagle. He must not be a coward: the lion.

Nor should he lose himself in fanciful flights of thought but

rather stand firmly on earth and be practical: the bull. The

final result should be “man,” and it should speak

to man. This is what one would like to see happen, that

everything passed on from man to man be conducted on a human

level.

Well,

I did have time after all to get to your question after looking

at those subjects I started with. I hope my answer was

comprehensible. Were you interested in the description of the

ear? One should know these things; one should be familiar with

what is contained in the various organs that one carries around

within the body.

Question: Is there time to say something about

the “lotus flowers” that are sometimes

mentioned?

Dr.

Steiner: I'll get to that when I describe the individual

organs to you.

|