|

VII

Spiritual-Scientific Foundations for a

True Physiology

Gentlemen, this time let us finish answering a question raised

the other day.

By

virtue of his skin, man is an entire sense organ. The skin of

the human being is something extraordinarily complicated

and truly marvellous. When we trace it from the outside inward,

we find first a transparent and horny layer called the

epidermis. It is transparent only in us white Europeans;

in Africans, Indonesians and Malayans, it is saturated with

coloured granules and thus tinged with colour. It is called

“horny” because it consists of the same substance,

arranged a little differently, from which the horns of animals

and our nails and hair are fashioned. Our nails actually grow

out of the uppermost layer of the skin. Under this layer lies

the dermis, which consists of an upper and a lower layer. So we

are in fact covered and enclothed with a three-layered skin:

the outer epidermis, the middle layer of the dermis and the

lower part of the dermis.

The

lowest layer of the dermis nourishes the whole skin; it stores

the nourishing substances for the skin. The middle layer is

filled with all kinds of things, but in particular it is filled

with muscle fibres. Everywhere in this layer are myriad tiny

onion-like things, one next to the other; we have

thousands upon thousands in our skin. We can call them

“onions” because the distinguishing feature of an

onion is its many peels, and these little corpuscles have such

“onion peels”; the onion skin is on the surface,

and the other, thinner part is on the inside. They were

discovered by the Italian Pacini and are therefore called

“Pacinian corpuscles.”

Around

these microscopic corpuscles are from twenty to sixty such

peels, so you can imagine how small they are.

Man is

constituted in such a way that he has these microscopic

little bulbs over the whole surface of his body. The largest

number is found — in snakes as well as in men — on

the tip of the tongue. Yes, it is almost comical, but most are

found on the tip of the tongue! There are many on the tips of

the fingers, on the palms of the hands and on other parts of

the body, but most are on the tip of the tongue. For

example, there are seven times more such little nerve

bulbs on the tip of the tongue than there are on the finger

tips.

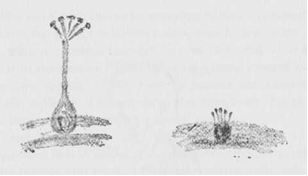

A

nerve fibre originates from each of these corpuscles and finds

its way into the brain via the spinal marrow. All these nerve

fibres radiate from the brain, and everywhere in the body they

form such nerve bulbs on its surface. So these nerve fibres in

the brain go everywhere and eventually form the onions within

the skin or dermis. It is interesting to realize that just as

real onions grow in the ground and form onion blossoms above,

so do these onions grow in the human body. There (pointing to

his sketch) are the onions and the stem within. In those nerves

of the tongue the stem is rather short, but in other nerves it

is sometimes quite long. The nerve fibres going from the feet

into the brain through the spinal marrow are extremely long.

Everything that we have as onions in our skin actually has

blossoms within our skull. You may imagine, then, that in

regard to his skin man is a kind of soil; it is strangely

formed, but it still is a kind of soil. On the surface is the

epidermis, in which various crystal substances are

deposited. Below are the solid masses of the body, and above is

the layer of “humus.” Going from outside

inward, beneath the hard, horny layer of the epidermis lies the

dermis, which is the soil. From it grow all these onions that

have blossoms in the brain. Their stems pass up into the brain

and have blossoms there.

Well,

gentlemen, in us older fellows things are such that only during

sleep can we properly trace this network, but in a child it is

still much in evidence. The child has a lively nerve bulb

activity in the nerves as long as its intellect is unawakened;

that is, throughout its first year, and just as the sun shines

over the blossoms of the onions, so shines the light into the

child that as yet does not translate with the intellect

what it receives with its eyesight. This is indeed like the sun

shedding its rays inside the head and opening up all the onion

blossoms. In the nerves of the skin we carry a whole plant

kingdom around within us. Later, however, when we enter grammar

school this lively growing comes to an end, and then we use the

forces from the nerves for thinking. We draw these forces

out and use them for thinking. This is extremely interesting.

Ordinarily, it is assumed that the nerves do the thinking, but

the nerves do not think. We can employ the nerves for thinking

only by stealing their light, so to speak. The human soul

steals the light from the nerves, and it uses what it has taken

away for thinking. It is really so. When we truly ponder the

matter, we finally recognize at every point the

independently active soul.

We

have such inwardly growing onions in common with all animals.

Even the lowest forms, which have slimy, primitive

shapes, possess sensory nerves that end in a kind of onion on

the surface. The higher we ascend toward man, the more are

certain of these nerve onions transformed in a specific manner.

The nerves of the taste buds, for example, are such transformed

skin nerves.

Now,

we possess these sensory bulbs at the tip of the tongue and

that is why it is so sensitive. We taste on the back of the

tongue and on the soft palate where such little onions are

dispersed. Actually, they sit there in a little groove and

within these grooves an onion penetrates into the nerves and

pushes into the dermis as a nerve corpuscle. First, a tiny

groove forms behind the tongue, and then an onion pushes itself

into this groove. The root of the onion penetrates all the way

to the surface of the tongue. On the base of the tongue are a

tremendous number of tiny grooves, and in each little groove a

“bulb” grows up from below. This accounts for our

experience of taste.

We can

be aware of everything with the sense of touch, or these onions

located on our body's surface. Now, you know that what one

feels one does not remember so well. I know with my feeling

that a chair is hard because I feel its hardness with a certain

number of nerve bulbs that constantly change, but my

memory is not strained by this sensation. With the sense of

taste it makes a little, though unconscious effort. Gourmets,

however, always know beforehand what is good, not afterward

when they have already tasted it, and that is why they order

it.

So the

nerve corpuscles pass through the spinal marrow directly into

the brain and form blossoms there. Everything that we want to

taste, however, must first be dissolved by the saliva in the

mouth; we can taste nothing that hasn't first been transformed

into fluid. But what is it that tastes? We would not be able to

taste anything if we did not have fluid within us. Our solid

human constitution, everything that is solid in the body, does

not taste. Our inner fluid mixes with what is dissolved of the

food. Thus, we can say that our own fluid mixes with the fluid

from without. The solid part of the human organization does not

taste anything. Our constitution is ninety percent water,

and here, around the papillae of the tongue, it is in an

especially fluid state. Just as water shoots out of a geyser,

so do we have such a spurting forth of fluid on the tip of the

tongue.

Saliva

that has been spit out of the mouth is no longer part of me,

but as long as that fluid is within the little gland of the

tongue, it belongs to me as a human being, just as my muscles

belong to me. I consist not only of solid muscles but also of

water, and it is this fluid that actually does the tasting

because it mixes with what comes as fluid from without. What

does one do when one licks sugar? One drives saliva from within

toward the taste buds. The dissolved sugar penetrates the

fluid, and the “fluid man,” as it were,

permeates himself with the sugar. The sugar is secreted

delicately in the taste buds of the tongue and spreads

out in one's own fluidity, giving him a feeling of

well-being.

As

human beings we can only taste, but why is this so? If we had

fins and were fishes — which would be an interesting

existence — every time we ate, the taste would penetrate

right through our fins. But then we would have to swim in

water, where we would find everything even the delicate

substances well-dissolved. The fish tastes all the traces of

substances that are in the water and follows the direction of

its taste, which is constantly penetrating into the fins. If

something pleasant flows in its direction, the fish will taste

it, and its fins will immediately move toward it. We men cannot

do what the fish can because we have no fins; in us they are

completely lacking. But since we cannot use the sensation of

taste to move around, we intensify it within. Fishes have a

highly developed sense of taste, but they have no inward sense

of it. We human beings have the taste within, we

experience it; fishes exist in the totality of the water

and experience taste together with the surrounding water.

People have wondered why a fish swims far out into the ocean

when it wants to lay its eggs. They swim far out, not only into

the Atlantic Ocean, but also into other parts of the earth's

oceans, and then the young slowly return to European waters.

Why is this? Well, European fishes that swim around in our

rivers are fresh-water fishes, but the eggs cannot mature in

fresh water. Fishes sense by taste that a trace of salt flows

toward the outlet of a river; they then swim out into the sea.

If the sun shines differently on the other side of the earth,

they taste that and by this sense swim halfway around the

globe. Then the young taste their way back again to where the

parent fishes have dwelt. So we see that fishes follow their

taste in every way.

It is

extremely interesting that the water that flows in the rivers

and is contained in the seas is full of taste, and the fact

that fishes swim around in them is really due to the water's

taste. It is actually the taste of the water that makes them

swim around; the taste of the water gives them their

directions. Naturally, if the sun shines on a certain

portion of water, everything that is in the water at that spot

is thoroughly dissolved by the heat of the sun. It is

changed into another taste, and that is why you see a lot of

fishes swimming around there; it is the taste.

It is

really a strange matter, gentlemen, because we would actually

be swimming, too, if we went only by our taste. When I taste

sugar the fluid man within me wants to swim toward it. The urge

to swim is indeed there; we want to swim constantly according

to our taste, but the solid body prevents us from doing so.

From that element that continually would like to swim but

cannot — we really have something like a fish within us

that constantly wants to swim but is held back — we

retain what our inner soul being makes out concerning

taste. With taste we live completely within the etheric body,

but the etheric body is held fast by the water in us, and that

water in turn is held by our physical body. It is the most

natural thing to say that man has an etheric body that is

really not disposed to walking on the earth. It is suited

only for swimming; it is in fact fish-like, but because man

makes it stand erect it becomes something different. Man has

within him this etheric body that is actually only in his fluid

organization, and it is indeed so that he would

constantly like to swim, swim in the elements of water that are

contained even in the air. We would like to be always swimming

there, but we transform this urge into the inner experience of

taste.

You

see, such aspects really lead one to comprehend the human

being. You cannot find this in any modern scientific book

because people examine not the living human being but only the

corpse, which no longer wants to swim. Nor does it participate

any longer in life. We participate in life because actually we

are the sum of everything existing in the world. We are fishes,

and the water vapor that is similar to us is something in which

we would like to be constantly swimming about. The fact that we

cannot do so results in our pouring it into us and tasting it.

The fishes are really cold creatures. They could taste things

marvellously well that are dissolved in the water, but they do

not do so because they immediately move their fins. If the fins

would disappear from the fishes, they would become higher

animals and would begin to have sensations of taste.

The

nerve bulbs that I told you about last time are

differently transformed “onions.” They

penetrate into the mucous membrane of the nose, but they do not

sit within a groove from which fluid seeps out; they reach all

the way to the surface. That is why these nerve bulbs can

perceive only what comes close to them. This means that we have

to let the fragrance of the rose come up to the nerve

bulb of our nose before we can smell it. Thus, one part of the

human body has the function of fashioning in a special way

these nerve bulbs, which are spread out over the whole skin, in

order to sense smells permeating the air.

Not

only does the outer air waft toward man, but also the breath

streams out from within him. The breath constantly passes

through the nose, and within this breath lives the air being of

man. We are water, and as I told you earlier, we are also air.

We do not have the air within us just for the fun of it. Like

the water within me, my breath is not solid. Just as when I

reach out my hand and feel that I have stretched out something

solid, so I stretch what I contain in my air organism

into my nose. There I grasp the fragrance of the rose or

carnation. Indeed, I am not only a solid being but

continually a being of water and air as well. We are the

air as long as it is within us and is alive. When we stretch

our “air hands” through the nose and grasp the

fragrance of a rose or carnation — bad odors, too,

of course — we do not touch it with our hand but rather

grasp it with the nerve bulbs, which attract the breath from

within so that it can take hold of the fragrance.

This

is something that is manifest also in the dog. I have told you

that as soon as the nose smells, the tail wags. Just as with

fishes the fins start to move about, so, too, with dogs the

tail starts to move. But what does this tail that can only wag

really want to do? This is most interesting. The tail can only

wag, but what does it really want to do? You see, gentlemen,

the dog would really like to do something quite different. If

it were not a dog but a bird it would fly under the influence

of smell. Just as fishes swim, a dog would fly if it were a

bird. Well, of course, a dog has no wings, and so he uses the

substituted organ and just wags his tail. It isn't enough

for flying, but it involves the same expenditure of

energy. In human beings it is the same. Because we always have

delicate sensations of smell that we do not even notice,

we would constantly like to fly.

Think

now of the swallows that live here in summer. What arises as

scents from the flowers is pleasing to them, and because it is

pleasing to their organ of smell they remain here. But when

autumn comes or is just approaching, the swallows, if they

could communicate among themselves, would say, “Oh, it's

beginning to smell bad!” The swallow has an

extraordinarily delicate sense of smell. You remember

that I told you that people are perceptible to savage tribes

all the way to Arlesheim. Well, for swallows the odour arising

in the south is perceptible when fall is approaching; it

actually spreads out all the way to the north. While in the

south it smells good, up north it begins to smell of decay. The

swallows are attracted to the good odour and fly south.

Whole

libraries have been written about the flight of birds, but the

truth is that even during the great migrations in spring and

autumn the birds follow the extremely delicate dispersion of

odours in the whole atmosphere of the earth. The organ of smell

in the swallows guides them to the south and then back again to

the north. When spring arrives here in our lands, it starts to

smell bad for the swallows down south. When the delicate

fragrances of spring flow southward to them, they fly

back north. It is really true that the whole earth is one

living being and that the other beings belong to it.

In our

body, things are so organized that the blood flows to the head

and then away from it. On the earth, things are so arranged

that the migratory birds fly to the equator and then back to

their point of departure. We, too, are influenced by the air

because the air we breathe drives the blood to the head.

Insofar as we are beings of air, we are completely

permeated with smell. For example, a person who walks

across a field that has just been fertilized with manure is

really going there together with his airy being. The

solid man and the fluid man do not notice the manure, but the

man of air does, and then there arises in him, understandably

enough, the urge to fly away. When the manure's stinking odour

rises from the field, he would actually like to fly off into

the air. He cannot do so because he lacks the wings and thus

reacts inwardly to what he cannot fly away from; it becomes an

internal process of the soul. As a result, man inwardly

becomes permeated with the manure odour, with the evaporations

that have become gaseous and vapor-like. He becomes suffused

with the bad odour and says that he loathes it. His loathing is

a reaction of the soul.

In the

fluid man there exists the more delicate airy form that, in a

way, he takes from the fluid organization of himself. It

is through this that he can taste. Likewise, something lives in

this airy form that we constantly renew in us through inhaling

and exhaling. Each moment it is expelled and reborn; it is born

eighteen times a minute and dies eighteen times a minute. It

takes years for the solid form to die, but the airy form dies

during exhalation eighteen times a minute and is born during

inhalation. It is a continuous process of dying and being born.

What is extracted within is the astral body. As I told you the

other day, it is the astral body that reverses the forces of

tail-wagging that should really be down below. Because these

forces are pushed up and against the sense of smell, we are

able to think. The brain grows to meet the nose under the

influence of the astral body, and no one can really understand

the brain who does not look at the whole matter in the way I

have just done. This understanding results from a correct

observation of our senses.

On

account of our sense of smell we would always like to be

flying. The bird can fly but we cannot; at best we have these

solid shoulder blades. Why can the bird fly? Gentlemen,

the bird has something peculiar that enables it to fly; it has

hollow bones. Air is inside them and the air that the bird

absorbs through its organ of smell comes into contact with the

air that it has in its bones. Indeed, the bird is primarily a

being of air. Its most important aspect consists of air; the

rest is merely grown on to it. The many feathers a bird may

have are actually all dried up. The most significant thing,

even in the ostrich, is that a bit of air is still contained in

each downy feather and all this air is connected with the air

outside. The ostrich walks because it is too heavy to fly

but, of course, the other birds do.

We

human beings have only our shoulder blades attached to our

back, which are clumsy and solidly shaped. Although we would

constantly like to fly with them, we cannot. Instead, we push

the whole spinal marrow into the brain and begin to think.

Birds do not think. We have only to observe them properly to

realize that everything goes into their flight. It looks

clever, but it is really the result of what is in the air.

Birds do not think, but we do because we cannot fly. Our

thoughts are actually the transformed forces of flying. It is

interesting that in human beings the sense of taste changes

into forces of feeling. When I say, “I feel well,”

I would really like to swim. Since I cannot, this impulse

changes into an inner feeling of well-being. When I say,

“The odour of the manure repulses me,” I would

really like to fly away. But I cannot, and so I have the

thought, “This is disgusting; this odour is

repulsive!” All our thoughts are transformed smells. Man

is such an accomplished thinker because he experiences in the

brain, with that part I described earlier, everything that the

dog experiences in the nose.

As

human beings, we owe a lot to our nose. You see, people who

have no sense of smell, whose mucous membrane is stunted, also

lack a certain sense of creativity. They can think only through

what they have inherited from their parents. It is always good

that we inherit at least something; otherwise, if all our

senses were not rudimentarily developed, we could not live at

all. A person born blind also has inherited the interior

of what the eye possesses. He has this primarily because he is

not only a compact man but also a man of fluid and air.

We

have now seen how strange all this is. We perceive solid

substances with our sense of touch through the nerve bulbs that

penetrate the skin everywhere; we become aware of watery

substances with our sense of taste; what is of air, the

vaporous, is recognized by us through the nerve bulbs that

penetrate into the mucous membrane of the nose. We also sense

something else around us, though in a more general way; that

is, heat and cold. So, as human beings we are partly solid,

water, air, and warmth, since we are usually warmer than

the surrounding world.

You

see, science does not really know that the aspect of tasting

concerns the man of water and that the element of smell

pertains to the man of air. Because the nerves of taste come

into the taste buds, it is the scientific opinion that these

nerves actually taste. But this is nonsense. In the mouth, it

is the fluid of the watery organization of man that tastes, and

in the nose, it is the element of air that smells. Furthermore,

the part of us that is warmth perceives heat and cold. The

internal warmth in us directly perceives the external

warmth, and this is the difference between the sense of warmth

and all the other senses. Warmth is produced by all the organs,

and as human beings we harbour a world of warmth within us.

This element of warmth perceives the other world of warmth

around us. When we touch something that is hot or cold, we

naturally perceive it just on the spot where we have touched

it. But when it is cold in winter or hot in summer, we perceive

this coldness or heat in our surroundings; we become a complete

sense organ.

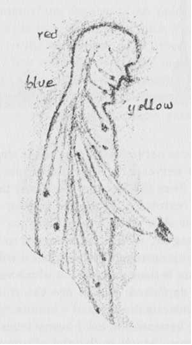

We can

see how science errs in this regard. According to scientific

books, the human being is some kind of compactly shaped form.

All the bones are drawn on the paper; the muscles and nerves

are all there. But this is utter nonsense because it represents

no more than one tenth of the human being. The rest is up to

ninety percent water, and then we must account for the air and

the warmth within. In fact, three more persons — of

water, air and warmth — should be sketched into the

figures drawn up by materialistic science. Man cannot be

comprehended in any other way. Only because we are warmer than

our surroundings and are also a portion of a world of warmth do

we experience ourselves as being independent in the

world. If we were as cold as a fish or a turtle, we would

have no ego; we could not speak of ourselves as

“I.” We could never think if we had not transformed

the sense of smell within us, or, in other words, if we had no

astral body. Likewise, we would have no ego if we did not

possess a portion of warmth within us.

Now,

someone might say that the higher animals have their own body

temperature, too. Yes, gentlemen, but they are burdened by

their warmth. The higher animals would like to become an

“I” but cannot. Just as we cannot swim or fly, the

higher animals would like to become an “I” but

cannot do it. You can discern that in their forms; they

would really like to become an “I,” and because

they cannot they assume their various shapes.

So, as

human beings we have four parts in us: the solid man, which is

the physical, material part; the fluid man, which carries the

more delicate body — the life body or etheric body

— within itself; the air being, the man of air who

constantly dies and is renewed in the physical realm but

who contains the astral body, which remains throughout life;

the portion of warmth, the ego man.

The

sense of warmth is distributed delicately over the whole human

being. Here science does something peculiar.

When

we examine the human being from a purely materialistic

standpoint, we discover these nerve bulbs that I have described

to you. Now, people say to themselves, “If I touch this

box, I feel it and its solidness because of the nerve bulbs. If

the box were cold, I would also feel the cold through such a

nerve bulb.” They constantly look for these nerve bulbs

of warmth and these nerve bulbs of feeling, but they never find

them. Someone will examine a piece of skin, and because some of

these nerve bulbs for feeling look a little different he thinks

that they belong to something else. But it is all

nonsense. There are no nerve bulbs sensitive to warmth

because the whole human being is perceptive to warmth. These

nerve bulbs are used only for sensing solid, water and

vaporous substances. Where the sense of warmth begins, we

become extremely “light-sensed” beings, that is, no

more than a bit of warmth that perceives exterior heat. When we

are surrounded by an amount of heat that enables us

properly to say “I” to ourselves, we feel

well, but when we are surrounded by freezing cold that

takes away from us the amount of warmth that we are, we are in

danger of losing our ego. The fear in our ego makes the cold

outside perceptible to us. When somebody is freezing he

is actually always afraid for his ego, and with good reason,

because he pushes the ego out of himself faster than he

actually should.

These

are the aspects that will gradually lead us from the

observation of the physical to the observation of the

nonphysical, the non-material. Only in this way can we

begin to comprehend man. Having mentioned all this, we shall be

able to continue with quite interesting observations next

time.

|