VIII

AY before yesterday I tried to show that the anthroposophical

knowledge which accompanies an inner life of the soul does not estrange

one from artistic awareness and creation. On the contrary, whoever takes

hold of Anthroposophy with full vitality opens up within himself

the very source of such activity. And I indicated how the meaning of

any art is best read through its own particular medium.

After

discussing architecture, the art of costuming, and sculpture,

I went on to explain the experience of color in painting, and took pains

to show that color is not merely something which covers the surface

of things and beings, but radiates out from them, revealing their inner

nature.

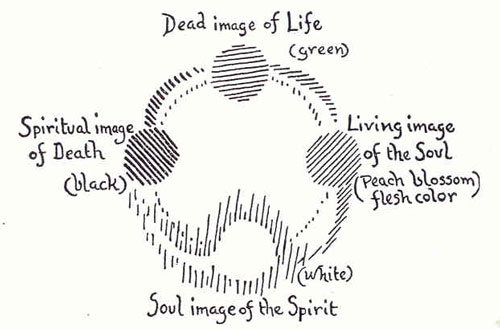

For

instance, I pointed out that green is the image of life, revealing

the life of the plant world. Though it has its origin in the plant's

dead mineral components, it is yet the means whereby the living shows

forth in a dead image. It is fascinating that life can thus reveal

itself. In that connection, consider how the living human figure appears

in the dead image of sculpture; how life can be expressed through dead,

rigid forms. In green we have a similar case in that it appears

as the dead image of life without laying claim to life itself.

I shall

repeat still other details from the last lecture in order to show how

the course of the world moves on, then returns into itself; and shall

do this by presenting the colors which make up its various elements:

life, soul, spirit. I said I would draw this complete circle of the

cosmic in the world of color. As I told you before, green appears as

the dead image of life; in green life lies, as it were, concealed.

| |

Diagram 1

Click image for large view | |

If

we take the flesh color of Caucasian man, which resembles spring's

fresh peach-blossom color, we have the living image of the soul. If

we contemplate white in an artistic way, we have the soul image of the

spirit. (The spirit as such conceals itself.) And if, as artists, we

take hold of black, we have the spiritual image of death. And the circle

is closed.

I have

apprehended green, flesh color, white and black in their aesthetic

manifestation; they represent the self-contained life of the cosmos

within the world of color. If, artistically, we focus attention upon

this closed circle of colors, our feeling will tell us of the need to

use each of them as a self-contained image.

Naturally,

in dealing with the arts I must concern myself not with abstract intellect,

but aesthetic feeling. The arts must be recognized artistically. For

that reason I cannot furnish conceptual proof that green, peach-blossom,

white and black should be treated as self-contained images. But it is

as if each wants to have a contour within which to express itself. Thus

they have, in a sense, shadow natures. White, as dimmed light, is the

gentlest shadow; black the heaviest. Green and peach-blossom are images

in the sense of saturated surfaces; which makes them, also, shadowlike.

Thus these four colors are image or shadow colors, and we must try to

experience them as such.

The matter

is quite different with red, yellow and blue. Considering these colors

with unbiased artistic feeling, we feel no urge to see them with well-defined

contours on the plane, only to let them radiate. Red shines toward us,

the dimness of blue has a tranquil effect, the brilliance of yellow

sparkles outward. Thus we may call flesh color, green, black and white

the image or shadow colors, whereas blue, yellow and red are radiance

or lustre colors. To put it another way: In the radiance, lustre and

activity of red we behold the element of the vital, the living; we may

call it the lustre of life. If the spirit does not wish merely to reveal

itself in abstract uniformity as white, but to speak to us with such

inward intensity that our soul can receive it, then it sparkles in yellow;

yellow is the radiance or lustre of the spirit. If the soul wishes

to experience itself inwardly and deeply, withdrawing from external

phenomena and resting within itself, this may be expressed artistically

in the mild shining of blue, the lustre of the soul. To repeat: red

is the lustre of life, blue the lustre of the soul, yellow the lustre

of the spirit.

Colors

form a world in themselves and we understand them with our feelings

if we experience the lustre colors red, yellow, blue, as bestowing a

gleam of revelation upon the image colors, peach-blossom, green, black

and white. Indeed, we become painters through a soul experience of the

world of color, through learning to live with the colors, feeling what

each individual color tries to convey. When we paint with blue we feel

satisfied only if we paint it darker at the edge and lighter toward

the center. If we let yellow speak its own language, we make it strong

in the center and gradually fading and lightening toward the periphery.

By demanding this treatment, each reveals its character. Thus forms

arise out of the colors themselves; and it is out of their world that

we learn to paint sensitively.

If we

wish to represent a spiritually radiant figure, we cannot do otherwise

than paint it a yellow which decreases in strength toward its edge.

If we wish to depict the feeling soul, we can express this reality with

a blue garment — a blue which becomes gradually lighter toward

its center. From this point of view one can appreciate the painters

of the Renaissance,

Raphael,

Michelangelo

even

Leonardo,

for they still

had this color experience.

In the

paintings of earlier periods one finds the inner or color-perspective

of which the Renaissance still had an echo. Whoever feels the radiance

of red sees how it leaps forward, how it brings its reality close, whereas

blue retreats into the distance. When we employ red and blue we paint

in color-perspective; red brings subjects near, blue makes them retreat.

Such color-perspective lives in the realm of soul and spirit.

During

the age of materialism there arose spatial perspective, which takes

into account sizes in space. Now distant things were painted not blue

but small; close things not red but large. This perspective belongs

to the materialistic age which, living in space and matter, prefers

to paint in those elements.

Today

we live in an age when we must find our way back to the true nature

of painting. The plane surface is a vital part of the painter's media.

Above everything else, an artist, any artist, must develop a feeling

for his media. It must he so strong that — for instance —

a sculptor working in wood knows that human eyes must be dug out of

it; he focuses on what is concave; hollows out the wood. On the other

hand, a sculptor working in marble or some other hard substance does

not hollow out; he focuses his attention on, say, the brow jutting forward

above the eye; takes into consideration what is convex. Already in his

preparatory work in plasticine or clay he immerses himself in his material.

The sculptor in marble lays on; the woodcarver takes away, hollows out.

They must live with their material; must listen and understand its vital

language.

The same

is true of color. The painter feels the plane surface only if the third

spatial dimension has been extinguished; and it is extinguished if he

feels the qualitative character of color as contributing another kind

of third dimension, blue retreating, red approaching. Then matter is

abolished instead of — as in spatial perspective — imitated.

Certainly I do not speak against the latter. In the age which started

with the fifteenth century it was natural and self-evident, and added

an important element to the ancient art of painting. But today it is

essential to realize that, having passed through materialism, it is

time for painting to return to a more spiritual conception, to return

to color-perspective.

In discussing

any art we must not theorize but (I repeat) abide, feelingly, within

its own particular medium. In speaking about mathematics, mechanics,

physics, we must kill our feeling and use only intellect. In art, however,

real perception does not come by way of intellect, art historians of

the nineteenth century notwithstanding. Once a Munich artist told me

how he and his friends, in their youth, went to a lecture of a famous

art historian to find out whether or not they could learn something

from him. They did not go a second time, but coined an ironical derogatory

phrase for all his theorizing. What can be expressed through the vital

weaving of colors can also be expressed through the living weaving of

tones. But the world of tones has to do with man's inner life (whereas

the sculptor in three-dimensional space and the painter on a

two-dimensional plane express what manifests etherically in space).

With the musical element we enter man's inner world, and it is extremely

important to focus attention upon its meaning within the evolution of

mankind.

Those

of my listeners who have frequently attended my lectures or are

acquainted with anthroposophical literature know that we can go back

in the evolution of mankind to what we call the Atlantean epoch when

the human race, here on earth, was very different from today, being

endowed with an instinctive clairvoyance which made it possible to behold,

in waking dreams, the spiritual behind the physical. Parallel to this

clairvoyance man had a special experience of music. In those ancient

days music gave him a feeling of being lifted out of the body. Though

it may seem paradoxical, the people of those primeval ages particularly

enjoyed the chords of the seventh. They played music and sang in the

interval of the seventh which is not today considered highly musical.

It transported them from the human into the divine world.

During

the transition from the experience of the seventh to that of the

pentatonic scales, this sense of the divine gradually diminished.

Even so, in perceiving and emphasizing the fifth, a feeling of liberating

the divine from the physical lingered on. But whereas with the seventh

man felt himself completely removed into the spiritual world, with the

fifth he reached up to the very limits of his physical body; felt his

spiritual nature at the boundary of his skin, so to speak, a sensation

foreign to modern ordinary consciousness.

The age which

followed the one just described — you know this from the history

of music — was that of the third, the major and minor third. Whereas

formerly music had been experienced outside man in a kind of ecstasy,

now it was brought completely within him. The major and minor third,

and with them the major and minor scales, took music right into man.

As the age of the fifth passed over into that of the third man began

to experience music inwardly, within his bounding skin.

We see

a parallel transition: on the one hand, in painting the spatial perspective

which penetrates into space; on the other, in music, the scales of the

third which penetrate into man's etheric-physical body; which is to

say, in both directions a tendency toward naturalistic conception. In

spatial perspective we have external naturalism, in the musical experience

of the third “internal” naturalism.

To grasp the essential

nature of things is to understand man's position in the cosmos. The

future development of music will be toward spiritualization, and involve

a recognition of the special character of the individual tone. Today

we relate the individual tone to harmony or melody in order that, together

with other tones, it may reveal the mystery of music. In the future

we will no longer recognize the individual tone solely in relation to

other tones, which is to say according to its planal dimension, but

apprehend it in depth; penetrate into it and discover therein its affinity

for hidden neighboring tones. And we will learn to feel the following:

If we immerse ourselves in the tone it reveals three, five or more tones;

the single tone expands into a melody and harmony leading straight into

the world of spirit. Some modern musicians have made beginnings in

this experience of the individual tone in its dimension of depth; in

modern musicianship there is a longing for comprehension of the tone

in its spiritual profundity, and a wish — in this as in the other

arts — to pass from the naturalistic to the spiritual element.

Man's

special relationship to the world as expressed through the arts becomes

clear if we advance from those of the outer world, that is architecture,

art of costuming, sculpture and painting, to those of the inner world,

that is to music and poetry. I deeply regret the impossibility of carrying

out my original intention of having Frau Dr. Steiner illustrate, with

declamation and recitation, my discussion of the poetic art. Unfortunately

she has not yet recovered from a severe cold. During this Norwegian

lecture course my own cold forces me to a rather inartistic croaking,

and we did not want to add Frau Dr. Steiner's.

Rising to poetry,

we feel ourselves confronted by a great enigma. Poetry originates in

phantasy, a thing usually taken as synonymous with the unreal, the

non-existent, with which men fool themselves. But what power expresses

itself through phantasy?

To understand

that power, let us look at childhood. The age of childhood does not

yet show the characteristics of phantasy. At best it has dreams. Free

creative phantasy does not yet live and manifest in the child. It is

not, however, something which, at a certain age in manhood, suddenly

appears out of nothingness. Phantasy lies hidden in the child; he is

actually full of it. What does it do in him? Whoever can observe the

development of man with the unbiased eye of the spirit sees how at a

tender age the brain, and indeed the whole of his organism, is still,

as compared with man's later shape, quite unformed. In the shaping of

his own organism the child is inwardly the most significant sculptor.

No mature sculptor is able to create such marvelous cosmic forms as

does the child when, between birth and the change of teeth, it plastically

elaborates his organism. The child is a superb sculptor whose plastic

power works as an inner formative force of growth. The child is also

a musical artist, for he tunes his nerve strands in a distinctly musical

fashion. To repeat: power of phantasy is power to grow and harmonize

the organism.

When the

child has reached the time of the change of teeth, around his seventh

year, then advances to puberty, he no longer needs such a great amount

of plastic-musical power of growth and formation as, once, for the care

of the body. Something remains over. The soul is able to withdraw a

certain energy for other purposes, and this is the power of phantasy:

the natural power of growth metamorphosed into a soul force. If you

wish to understand phantasy, study the living force in plant forms,

and in the marvelous inner configuratons of the organism as created

by the ego; study everything creative in the wide universe, everything

molding and fashioning and growing in the subsconscious regions of the

cosmos; then you will have a conception of what remains over when man

has advanced to a point in the elaborating of his own organism when

he no longer needs the full quota of his power of growth and formative

force. Part of it now rises up into the soul to become the power of

phantasy. The final left-over (I cannot call it sediment, because sediment

lies below while this rises upward) — the ultimate left-over is

power of intellect. Intellect is the finely sifted-out power of phantasy,

the last upward-rising remainder.

People

ignore this fact. They see intellect as of greater reality. But phantasy

is the first child of the natural formative and growth forces; and because

it cannot emerge as long as there is active growing, does not express

direct reality. Only when reality has been taken care of does phantasy

make its appearance in the soul. In quality and essential nature it

is the same as the power of growth. In other words, what promotes growth

of an arm in childhood is the same force which works in us later, in

soul transformation, as poetic, artistic phantasy. This fact cannot

be grasped theoretically; we must grasp it with feeling and will. Only

then will we be able to experience the appropriate reverence for phantasy,

and under certain circumstances the appropriate humor; in brief, to

feel phantasy as a divine, active power in the world.

Coming

to expression through man, it was a primary experience for

those human beings of ancient times of whom I spoke in the last lecture,

when art and knowledge were a unity, when knowledge was acquired through

artistic rites rather than the abstractions of laboratory and clinic;

when physicians gained their knowledge of man not from the dissecting

room but from the Mysteries where the secrets of health and disease,

the secrets of the nature of man, were divulged in high ceremonies.

It was

sensed that the god who lives and weaves in the plastic and musical

formative forces of the growing child continues to live in phantasy. At

that time, when people felt the deep inner relationship between religion,

art and science, they realized that they had to find their way to the

divine, and take it into themselves for poetic creation; otherwise

phantasy would be desecrated.

Thus ancient

poetic drama never presented common man, for the reason that mankind's

ancient dramatic phantasy would have considered it absurd to let ordinary

human beings converse and carry out all kinds of gestures on the stage.

Such a fact may sound paradoxical today, but the anthroposophical

researcher — knowing all the objections of his opponents —

must nevertheless state the truth. The Greeks prior to Sophocles and

Aeschylus would have asked: Why present something on the stage which

exists, anyhow, in life? We need only to walk on the street or enter

a room to see human beings conversing and gesturing. This we see

everywhere. Why present it on a stage? To do so would have seemed

foolish.

Actors

were to represent the god in man, and above all the god who, rising

out of terrestrial depths, gave man his will power. With a certain

justification our predecessors, the ancient Greeks, experienced this

will-endowment as rising up out of the earth. The gods of the depths

who, entering man, endow him with will, these Dionysiac gods were to

be given stage presentation. Man was, so to speak, the vessel of the

Dionysiac godhead. Actors in the Mysteries were human beings who

received into themselves a god. It was he who filled them with

enthusiasm.

On the

other hand, man who rose to the goddess of the heights (male gods were

recognized as below, female gods in the heights), man who rose in order

that the divine could sink into him became an epic poet who wished not

to speak himself but to let the godhead speak through him. He offered

himself as bearer to the goddess of the heights that she, through him,

might look upon earth events, upon the deeds of Achilles, Agamemnon,

Odysseus and Ajax. Ancient epic poets did not care to express the opinions

of such heroes; opinions to be heard every day in the market place.

It was what the goddess had to say about the earthly-human element when

people surrendered to her influence that was worth expression in epic

poetry. “Sing, oh goddess, the wrath of Achilles, son of

Peleus”: thus did Homer begin the

Iliad.

“Sing, oh

goddess, of that ingenious hero,” begins the

Odyssey.

This is no phrase; it is a deeply inward confusion of a true epic poet who

lets the goddess speak through him instead of speaking himself, who

receives the divine into his phantasy, that child of the cosmic forces

of growth, so that the divine may speak about world events.

After

the times had become more and more materialistic, Klopstock, who still

had real artistic feeling, wrote his

Messiade.

Inasmuch as

man no longer looked up to the gods, he did not dare to say: Sing, oh

goddess, the redemption of sinful man as fulfilled here on earth by

the Messiah. He no longer dared to do this in the eighteenth century,

but cried instead: “Sing, oh immortal soul, of sinful man's

redemption.” In other words, he still possessed something which

was lifted above the human level. His words reveal a certain bashfulness

about what was fully valid in ancient times: “Sing, oh goddess,

the wrath of Achilles, son of Peleus.”

Thus the

dramatist felt as if the god of the depths had risen, and that he himself

was to be that god's vessel; the epic poet as if the Muse, the goddess,

had descended into him in order to judge earthly conditions. The ancient

Greek actor avoided presentation of the individual human element. That

is why he wore high thick-soled shoes, cothurni, and used a

simple musical instrument through which his voice resounded. He desired

to lift the dramatic action above the individual-personal.

I do

not speak against naturalism. For a certain age it was right and

inevitable. For when Shakespeare conceived his dramatic characters in

their supreme perfection, man had arrived at presenting, humanly, the

human element. Quite a different urge and artistic feeling held sway

at that period. But the time has come when, in poetic art also, we must

find our way back to the spiritual, to presenting dramatic figures in

whom man himself, as a spiritual as well as bodily being, can move within

the all-permeating spiritual events of the world.

I have

made a first weak attempt in my Mystery dramas. There human beings converse

not as people do in the market place or on the street, but as they

do when higher spiritual impulses play between them, and their instincts,

desires and passion are crossed by paths of destiny, of karma, active

through millennia in repeated lives.

It is

imperative to turn to the spiritual in all spheres. We must make good

use of what naturalism has brought us; must not lose what we have acquired

by having for centuries now held up, as an ideal of art, the imitation

of nature. Those who deride materialism are bad artists, bad scientists.

Materialism had to happen. We must not look down mockingly on earthly

man and the material world. We must have the will to penetrate into

this material world spiritually; nor despise the gifts of scientific

materialism and naturalistic art; must — though not by developing

dry symbolism or allegory — find our way back to the spiritual.

Symbolism and allegory are inartistic. The starting point for a new

life of art can come only by direct stimulation from the source whence

spring all anthroposophical ideas. We must become artists, not symbolists

or allegorists, by rising, through spiritual knowledge, more and more

into the spiritual world.

It can

be attained quite specially if, in the art of recitation and declamation,

we transcend naturalism. In this connection we should remember how genuine

artists like Schiller and Goethe formed their poems. In Schiller's soul

there lived an indefinite melody, and in Goethe's an indefinite picture,

a form, before ever they put down the words of their poems. Often, today,

the chief emphasis in recitation and declamation is placed on prose

content. But that is only a makeshift. The prose content of a poem,

what lies in the words as such, is of little importance; what is important

is the way the poet shapes and forms it. Ninety-nine percent of those

who write verse are not artists. In a poem everything depends on the

way the poet uses the musical element, rhythm, melody, the theme, the

imaginative element, the evocation of sounds. Single words give the

prose content. The crux is how we treat that prose content; whether,

for instance, we choose a fast or slow rhythm. We express joyful anticipation

by a fast rhythm. If we say: The hero was full of joyful anticipation,

we have prose even if it occurs in a poem. It is essential, in such

an instance, to choose a rapidly moving rhythm. When I say: The woman

was deeply sad, I have prose, even in a poem. But when I choose a rhythm

which flows in soft slow waves, I express sorrow. To repeat, everything

depends on form, on rhythm. When I say, The hero struck a heavy blow,

it is prose. But if the poet speaks in fuller, not ordinary tones, if

he offers a fuller u-tone, a fuller o-tone, instead of a's and e's,

he expresses his intention in the very formation of speech.

In declamation

and recitation one has to learn to shape language, to foster the elements

of melody, rhythm, beat, not prose content. One has also to gauge the

effect of a dull sound upon a preceding light sound, and a light sound

upon the following dark one, thus expressing a soul experience in the

treatment of the speech sounds. Words are the medium of recitation and

declamation: a little-understood art which we have striven to develop.

Frau Dr. Steiner has given years to it. When we return to artistic feeling

on a higher level we return to speech formation as contrasted with the

modern emphasis on prose content. Nothing derogatory shall be said against

prose content. Having achieved it through the naturalism which made

us human, we must keep it. At the same time we must again become imbued

with soul and spirit. Word-content can never express soul and spirit.

The poet is justified in saying: “If the soul speaks,

alas, it is no longer the soul that speaks.” For prose is not the

soul's language. It expresses itself in beat, rhythm, melodious theme,

image, and the formation of speech sounds. The soul is present as long

as the poem expresses rising and falling inner movements.

I make

a distinction between declamation and recitation: two separate arts.

Declamation has its home in the north; and is effective primarily through

the weight of its syllables: chief stress, secondary stress. In contrast,

the reciting artist has always lived in the south. In recitation man

takes into account not the weight but the measure of the syllables:

long syllable, short syllable. Greek reciters, presenting their texts

concisely, experienced the hexameter and pentameter as mirrors of the

relationship between breathing and blood circulation. There are

approximately eighteen breaths and seventy-two pulse-beats per minute.

Breath and pulse-beat chime together. The hexameter has three long

syllables, the fourth is the caesura. One breath measures four pulse

beats. This one-to-four relation appearing in the measure and scanning

of the hexameter brings to expression the innermost nature of man, the

secret of the relation of breath and blood circulation.

This reality cannot

be perceived with our intellect; it is an instinctive, intuitive-artistic

experience. And beautifully illustrated by the two versions of Goethe's

Iphigenie

when spoken one after the other. We have done that

often and would have done so today if Frau Dr. Steiner were not indisposed.

Before he went to Italy, Goethe wrote his

Iphigenie

as Nordic

artist (to use Schiller's later word for him), in a form which can be

presented only through the art of declamation, chief stress, secondary

stress, when the life of the blood preponderates. In Italy he rewrote

this work. It is not always noticed, but a fine artistic feeling can

clearly distinguish the German from the Roman

Iphigenie.

Because

Goethe introduced the recitative element into his Northern declamatory

Iphigenie,

this Italian, this Roman

Iphigenie

asks for an altered

reading. If one reads both versions, one after the other, the marvelous

difference between declamation and recitation becomes strikingly clear.

Recitation was at home in Greece where breath measured the faster blood

circulation. Declamation was at home in the North where man lived in

his inmost nature. Blood is a quite special fluid because it contains

the inmost human element. In it lives the human character. That is why

the Northern poetic artist became a declamatory artist.

As long

as Goethe knew only the North he was a declamatory artist and wrote

the declamatory German

Iphigenie;

but transformed it when he

had been softened to meter and measure through seeing the Italian

Renaissance art which he felt to be Greek. I do not wish to spin theories,

I wish to describe feelings which anthroposophists can kindle for the

world of art. Only so shall we develop a true artistic feeling for

everything.

One more

point. How do we behave on a stage today? Standing in the background

we ponder how we would walk down a street or through a drawing-room,

then behave that way on the stage. It is all right if we introduce this

personal element, but it does lead us away from real style in stage

direction, which always means taking hold of the spirit. On the stage,

with the audience sitting in front, we cannot behave naturalistically.

Art appreciation is largely immersed in the unconsciousness of the instincts.

It is one thing if with my left eye I see somebody walk by, passing,

from his point of view, from right to left, while, from mine, from left

to right. It is quite another thing if this happens in the opposite

direction. Each time I have a different sensation; something different

is imparted. We must relearn the spiritual significance of directions,

what it means when an actor walks from left to right, or from right

to left, from back to front, or vice versa; must feel the impossibility

of standing in the foreground when about to start a long speech. The

actor should say the first words far back, then gradually advance, making

a gesture toward the audience in front and addressing both the left

and right. Every movement can be spiritually apprehended out of the

general picture, and not merely as a naturalistic imitation of actions

on the street or in the drawing-room. Unfortunately people no longer

wish to make an artistic study of all this; they have become lazy.

Materialism permits indolence. I have wondered why people who demand

full naturalism — there are such — do not adopt a stage with

four walls. No room has three. But with a four-wall set how many tickets

would be sold?

Through

such paradoxes we can call attention to the great desideratum: true

art in contrast to mere imitation. Now that naturalism has followed

the grand road from naturalistic stage productions to the films (neither

philistine nor pedant in this regard, I know how to value something

for which I do not care too much) we must find the way back to presentation

of the spiritual, the genuine, the real; must refind the divine-human

element in art by refinding the divine-spiritual.

Anthroposophy

would take the path to the spirit in the plastic arts also. That was

our intention in building the Goetheanum at Dornach, this work of art

wrested from us. And we must do it in the new art of eurythmy. And in

recitation and declamation. Today people do breathing exercises and

manipulate their speech organism. But the right method is to bring order

into the speech organism by listening to one's own rhythmically spoken

sentence, which is to say, through exercises in breathing-while-speaking.

These things need reorientation. This cannot originate in theory,

proclamations and propaganda; only in spiritual-practical insight into

the facts of life, both material and spiritual.

Art,

always a daughter of the divine, has become estranged from her

parent. If it finds its way back to its origins and is again accepted

by the divine, then it will become what it should within civilization,

within world-wide culture: a boon for mankind.

I have

given only sketchy indications of what Anthroposophy wishes to do for

art, but they should make clear an immense desire to unfold the right

element in every sphere. The need is not for theory — art is not

theory. The need is for living, fully living, in the artistic quality

while striving for understanding. Such an orientation leads beyond

discussion to genuine appreciation and creation.

If art is to be fructified

by a world-conception, this is the crux of the matter. Art has always

taken its rise from a world-conception, from inner world-experience.

If people say: Well, we couldn't understand the art forms of Dornach,

we must reply: Can those who have never heard of Christianity understand

Raphael's

Sistine Madonna?

Anthroposophy

would like to lead human culture over into honest spiritual

world-experience.

|