Lecture II

Dornach, 1st November, 1916

In our last lecture we

showed the period of Art which finally merged into that of the great

masters of the Renaissance. We ended by revealing the connecting threads

in the artistic world of feeling, which finally led up to what was so

wondrously united in Leonardo, in Michangelo and in Raphael. Yet at the

same time, in these three masters we must also see the starting point

of the new age, in an artistic sense. It is the dawn of the 5th

post-Atlantean age, which is heralded in the realm of Art. All three

were living, at the beginning of the 5th post-Atlantean age. Leonardo

was born in 1452, Michelangelo in 1475 and Raphael in 1483; Leonardo

dies in 1519, Raphael in 1520, and Michelangelo in 1564. Here we find

ourselves at the starting point of the new age. At the same time,

something is contained in these artists which we must undoubtedly regard

as a culmination of the spiritual stream of preceding ages, inasmuch as

they poured their impulses into the realm of Art. It is true, my dear

friends, that in our time people have little understanding for what is

important in this respect, for in our time — I do not say this as

mere criticism — art has been far too much expelled from the

spiritual life as a whole. It is even considered a failing of the

historian or critic,

if he seeks once more to give Art its place in the spiritual life as

a whole. People say that our attention is thus diverted unduly from

the artistic or aesthetic impulses as such, attaching an excessive value

to the content, to the subject-matter, and yet, this need not be the

case at all. Indeed, it is only in our own time that this distinction

has acquired so much importance. It had no such direct significance

in former epochs — epochs when the artistic understanding was

more developed in the ordinary common sense of the people. We must not

forget how much has been done to extirpate a true artistic understanding

by all the atrocities which have been placed before the human mind of

men in recent times, by way of pictorial representation and the like.

True understanding for the manner of representation has been

lost. European humanity, in a certain sense, no longer cares how a given

subject-matter is presented to it. In wide circles, artistic understanding

has to a large extent been lost.

Speaking of former epochs,

and especially of the epoch to which we are now referring, we may truly

say artists such as Raphael, Michelango and Leonardo were by no means

one-sidedly artistic, but carried in their souls the whole of the

spiritual life of their time and created out of this. In saying this,

I do not mean that they borrowed their subject-matter from the spiritual

life of their time. I mean far more than this. Into the specifically

artistic quality of their creation, in form and colouring, there flowed

the specific quality of the world-conception of that time. In our time,

a world-conception is a collection of ideas which can, of course, be

represented in sculpture or in painting and it is frequently embodied,

needless to say, in forms and colours and the like which to the true

artistic sense will nevertheless

be an atrocity. In this respect, unfortunately, we must repeatedly utter

warnings, even within our anthroposophical stream of evolution. The

feeling for what is truly artistic is not always prevalent among us.

I still remember with a shudder how at the beginning of the theosophical

movement in Germany a man once came to me in Berlin, bringing with him

reproductions of a picture he had painted. The subject was: Buddha under

the Bodhi Tree. It is true there sat a huddled figure under a tree,

but the man — if you will pardon me the apt expression —

understood as little of Art as an ox, having eaten grass throughout

the week, understands of Sunday. He simply thought, here is the subject;

let us paint it, and it will represent a work of Art. Of course, it

represented something. Namely, he who imagined the scene to himself

— “Buddha under the Bodhi Tree” — could see

it so, no doubt. But there was absolutely no reason why such a thing

should ever have been painted.

It is a very different thing

when we say of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael, that they bore within

them the whole way of feeling which permeated the Italian civilisation

of their time. For this civilisation entered livingly into the artistic

quality of their work, into their whole manner of presentation; nor

can we fully understand these artists if we have no feeling for the

civilisation in the midst of which they lived. Today, indeed, people

believe the most extraordinary things. They will believe, for instance,

that a man can build a Gothic church even if he has not the remotest

notion of High Mass. Of course, he cannot do so in reality. Or they

believe that one can paint the Trinity even if one has no feeling for

what is intended to be living in it. In this way, Art is expelled from

its living connection with the spiritual life as a whole. At the same

time, on the other hand, people fail to understand the artistic element

as such, imagining that with aesthetic views and feelings which happen

to be prevalent today they can set to work and ciriticise Raphael or

Michelangelo or Leonardo, whose whole way of feeling was quite different.

It was only natural (though I should need many hours to say in full

what should be said on this point), it was only natural for them to

be living in the whole way of feeling of their time. We cannot understand

their creative work unless we understand the character which Christianity

had assumed at the time when these artists blossomed forth. You need

only remember that at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th

century Italian Christianity witnessed the rise even among the Popes, of

men who truly cannot be said to have satisfied even the most rudimentary

demands of morality, nor need one be in any way a pietist to say so.

And, of course, the whole army of priests were of like character. The

idea that a specific moral impulse must be living in what goes by the

name of “Christian” had been lost sight of, comparatively

speaking. And when in later times it emerged again — in pietist

and moralising forms, by no means identical with what I described the

other day when speaking of St. Francis, — it was imbued with quite

a different feeling of Christianity than inspired those who lived, for

instance, under an Alexander VI, a Julius II or a Leo X. If, on the

other hand, we consider the Christian traditions, the concepts and ideas

(and when I say ideas I include “Imaginations”) connected

with the Mystery of Golgotha, we find them still living in the souls

with an intensity of which the man of today has little notion. Human

souls lived in the ideas connected with the Mystery of Golgotha, as

in a world that was their very own, and they saw Nature herself in the

midst of this same world. We need but call to mind: In that time, even

for the most educated, this Earth, of which the Western half was still

unknown (or was only just begining to be known and was not fully really

reckoned with), — this Earth was the centre of the whole Universe.

Going down beneath the surface of the Earth, one found a subterranean

kingdom; going but a little way above, a super-earthly. We might almost

say, it was as though a man only need lift his arm, to grasp with his

hand the feet of the heavenly beings. Heaven still penetrated down into

the earthly element. Such was the conception — a harmony, an

interplay of the spiritual above and the Earth beneath it, with the

world of the senses which contained mankind. Even their view of Nature

was in this spirit.

Those, however, among whom

we find the three great masters of the Renaissance were striving forth

from yonder age. And the one who harbours within him, as in a seed,

all that came forth since then — nay, much that is still destined

to come forth, — that one is Leonardo. The soul of Leonardo was

equally inclined to the feelings of the former time and of the latter.

His soul had most decidedly a Janus head. By his education, by the habits

of his life, by all that he had seen, he lived with his feelings still

in the olden time. Yet he had a mighty impulse to that conception of

the world which only came forth in the succeeding centuries. He had

an impulse, not so much towards its width as to its depth. From various

indications in my other lectures, you know that the Greeks — and

even the men of later times during the 4th Post-Atlantean age —

knew life quite differently than we do, — that is to say, out

of a different source of knowledge. The sculptor, for example, knew

the human figure from within — from a perception of the forces

that were at work within himself, the forces which we today describe

in Anthroposophy as the etheric. Out of this inner feeling of the human

figure the Greek artist created. In course of time this faculty was

lost. Another faculty now had to appear: the power to take hold of things

with outward vision. Man felt impelled to feel and understand external

Nature. I showed you last time, how Francis of Assisi was among the

first who sought to perceive Nature through a deep life of feeling.

Now Leonardo was the first who endeavoured in a wider sense to add to

this feeling of Nature, a conscious understanding of Nature. Because

it was no longer given to him, as to the men of former ages, to trace

from within outward the forces that are at work in man, he tried to

know these things by contemplation from without. He tried to know by

outward vision what could no longer be made known by inward feeling.

An understanding of Nature as against a feeling for Nature: this is

what distinguishes Leonardo da Vinci from Francis of Assisi, and this

determines the whole constitution of his spirit. He was all out to

understand. And though we need not take it word for word — for

the sources, as a rule, relate only the current legends —

nevertheless, the legends themselves were founded upon fact, and there

is truth in it when we are told how Leonardo took especial pains to

study characteristic faces, so that by dint of outward contemplation

the working of the formative

forces of the human organism might become his own inner experience.

Often he would follow a character about for days and days, so that the

human being might become as if transparent to him, revealing how the

inner being works into the outer form. Yes, there is truth in this,

— and that he invited peasants to his house and set before them

tasty dishes or told them stories, so that their faces assumed every

possible expression of laughter and contortion and he could study them.

All this is founded upon fact. And when he had to paint a Medusa he

brought all manner of toads and reptiles into his studio, to study the

characteristic animal faces. These are legendary anecdotes; and yet

they truly indicate how Leonardo had to seek, to discover the mysterious

creation of Nature's forces. For Leonardo was truly a man who sought

to understand Nature. He tried in an even wider sense to understand

the forces of Nature as they play their part in human life. He was no

mere artist in the narrower sense of the word; the artist in him grew

out of the whole man, standing in the very midst of the turning-point

of time. The church of San Giovanni in Florence had sunk a little, owing

to a subsidence of the soil. He wished to raise it again — a task

that could easily be carried out today; but in that time such a thing

was considered absolutely hopeless. He wanted to have it raised bodily,

as it stood. Nowadays, as has justly been observed, it would only be

a question of the cost; in his time it was an idea of genius, for no

one beside Leonardo thought such a thing was possible. He also thought

of constructing machines whereby men would be able to fly through the air;

and of irrigating great areas of swamp. He was an engineer, a mechanic,

a musician, a cultured man in social intercourse, a scientist according

to his time. He constructed apparatus so unheard-of in that age that

no one else could make anything of them. What poured into his artist's

hand was working, therefore, from a many-sided understanding of the

world. Of Leonardo we can truly say, he bore his whole Age within him,

even as it came to expression in the profound external changes which

were then enacted in Italy. Leonardo's whole life — his artistic

life included — bears the stamp of this his fundamental character.

In spite of the fact that he grew out of the Italian environment, he

was not altogether at home there. True, he was a Florentine, but he

spent only his youth in Florence, and then went on to Milan, having

been summoned thither by the Duke Ludovico Sforza — sommoned by no

means (as we might naively imagine) as the great artist whom we recognise

in him today, but as a kind of court entertainer. From the skull of a

horse, Leonardo constructed an instrument of music, from which he enticed

various notes, and was thus able with great humour to entertain the ducal

house. We need not say that he was intended as a kind of

“fool,”

but as an entertainer to amuse the Court, most certainly. The works

of Art which he produced in Milan, to which we shall presently refer,

were certainly created out of the very deepest impulse of his own being.

But he had not been summoned to the Court of the Sforza's for this

purpose; and though he entered well into all the life at Milan, we find

him afterwards, on his return to Florence, working at a battle-picture,

intended to glorify a victory over Milan. Then we see him end his life

at the French Court.

The one dominating impulse

in Leonardo is to see and feel what interests the human being of his

time; the political events, complicated as they were, more or less swept

past him. He only skimmed off them, as it were, the uppermost and human

layer. Indeed, in many respects he rather gives us the impression of

an adventurer, albeit one endowed with colossal genius. He bears his

whole Age within him; and out of this feeling of his Age as a whole,

his creations arise. We shall present them not in chronological but

in a freely chosen order, for in Leonardo the main point is to see how

he creates out of a single impulse, and for this reason the chronological

sequence is less important.

An altogether different

nature, though possessing the characteristics of the Renaissance in

common with him, was Michelangelo.

If we can say of Leonardo that he

bore the whole forces of his time within him (and for this very reason

often came into disharmony with it and remained misunderstood, just

because he understood it in its depths, in the forces that only found

their way to the surface during later centuries), of Michelangelo, on

the other hand, we may say: he bore within him, above all, the Florence

of his time. What was the Florence of his time? It was, in a sense,

a true concentration of the existing order of the world. This Florence

he bore within him. Unlike Leonardo, he did not stand remote from

political

affairs. The complicated political events around him — and the

whole world-order of that time played into these politics — entered

again and again into the soul of Michelangelo. And when again and again

he went to Rome, he bore his Florence with him, and painting and sculpting

a Florentine element into the Roman setting. Leonardo bore a universal

feeling into the works he created; Michelangelo carried a Florentine

feeling into Rome. As an artist he achieved a kind of spiritual conquest

over Rome, making Florence arise again in Rome.

Thus Michelangelo entered

intensely into all that was taking place through the political conditions

in Florence during his long life. We see this in the succession of his

life-periods. As a young man, when his career was only just beginning,

he witnessed the reign of the great Medici, whose favourite he was,

and by whose favour he was enabled to partake in all that the Florence

of that time could offer to a man's spiritual life. Whatever of ancient

Art and artistry was then available, Michelangelo studied it under the

protectorate of the Medici; and it was here that he produced his earliest

work. Indeed, he loved his protector, and grew together in his own soul

with the soul-nature of the Medici. But presently he had to realise

that the sons of his patron were of quite a different kind. He who had

done so much for Florence — out of an ambitious disposition, it

is true, yet cultivating largesse and freedom — died in 1492;

and his sons proved themselves more or less common tyrants. Michelangelo

had to experience this change in comparatively early youth. Whereas

at the beginning of his career the mercantile spirit of the Medici had

allowed free play to Art, he must now witness this mercantile spirit

itself masquerading as a political spirit, and striving towards tyranny.

Yes, he witnessed on a small scale the rise in Florence of what was

afterwards to take hold of all the world. It was a terrible experience

for him, and yet not unconnected with the whole surrounding world of

the new Age. It was now that he first went to Rome, and we may say:

In Rome he mourns the loss of what he has experienced as the true

greatness

of Florence. We can even recognise how the plastic quality of his work

is connected with this great change in his feelings: Into the very line

we notice what the political changes in Florence had brought about in

his soul. Any one who has a deeper feeling for such things will see

in the Pieta in the Vatican a work which in the last resort is born

out of the mourning soul of Michelangelo — Michelangelo mourning

for the city of his fathers.

Then, when better times

returned and he went back to Florence, he stood once more under a new

impression. He felt uplifted in his soul, — Freedom had entered

into Florence once again. He poured out this new feeling into the

indescribably

great figure of his David. It is not the traditional David of the Bible.

It is the protest of free Florence against the encroaching principle

of “great powers,” of mighty States. Its colossal character

is connected with this very feeling.

Again, when he was summoned

by Pope Julius to decorate the Sistine Chapel, now in a far fuller sense

than before, he bore his Florence with him into Rome. What was it that

he bore with him? It was a whole world-conception, of which we can say

that it shows the rise of the new age, just as truly as we can say,

on the other hand, that in the works of Michelangelo in the Sistine

Chapel, representing the creation of the World and the great process

of Biblical history, we have the twilight of an ancient world-conception.

Thus Michelangelo carries with him a whole world to Rome, — carries

with him something that could never have arisen at that time in Rome

itself, but that could only arise in Florence: the idea of one mighty

cosmic process with all the Prophetic gifts and Sibylline faculties

of man. You will find further explanations on these things in earlier

lectures. These inner connections could only be felt and realised in

Florence. What Michelangelo experienced through all the spiritual life

that had reached its height in the Florence of that time, cannot, in

truth, be felt today, unless we transplant ourselves through Spiritual

Science into former epochs. Hence the usual histories of Art contain

so many absurdities at this point. A man can only create as Michelangelo

created if he believes in these things and lives in their midst. It

is easy for a man to say that he will paint the world's creation. Many

a modern artist would credit himself, no doubt, with this ability, —

but one who has true feeling will not be able to assent. No one can paint

the evolution of the world who does not live in it, like Michelangelo,

with all his being.

But when he returned once

more to Florence, he was already driven, after all, by the new stream,

which — to put it bluntly — replaces the sacramental by

the commercial character. True, he was destined still to create the

most wonderful works, in the Medici Chapel. But in the background of

this undertaking was an element which could not but inspire him with

melancholy feelings. The purpose was the glorification of the Medici.

It was they who mattered, — who in the meantime had become powerful,

albeit less in Florence than in the rest of Italy. Then once more the

political changes drove him back. The betrayal of the Malatestas, their

penetration into Florence, drove him back again to Rome. And now he

painted, as it were, into the Last Judgment, the protest of a Florentine,

the great protest of humanity, of the human individual against all that

would oppose it. Hence the real human greatness of his Last Judgment,

the greatness which it undoubtedly breathed forth, as it proceeded from

his hand. For now, also, parts of it have been completely spoiled.

But he still had to undergo

experiences which entered very, very deep into all the impulses of feeling

in his soul. How many events had he not experienced, how much did they

not signify for the development of his picture of the world: For the

things I have indicated were of great importance to him. They may be

taken abstractly today, but in the soul of Michelangelo they worked

without a doubt as very deep soul-impulses. But we must add that I have

mentioned the fact that he witnessed, too, the great change which came

over Florence through the appearance of Savonarola. This was a protest

within the life of the Church against what was characteristic of that

time in Christianity. So free an Art as was developed in Leonardo and

in many others like him could only unfold in this way inasmuch as the

ideas of Christianity were lifted out of their context and taken by

themselves. I mean the ideas connected with the Mystery of Golgotha

— the conception of the Trinity, of the Last Supper, of the

connection between the earthly and the spiritual realms, and so forth.

All these conceptions, lifted right out of the moral element, assumed

a free imaginative

character which the artist dealt with at his pleasure, treating it like

any worldly subject, with the only difference that it contained, of

course, the sacred figures. These things had been objectified, loosed

from the moral element; and thus the Christian thought, loosed from

the moral element, slid over by and by into a purely artistic sphere. All

this took place quite as a matter of course, and the gradual elimination

of the moral element was a natural concomitant of the whole process.

Savonarola represents the great protest against this elimination of

the moral element. Savonarola appears; it is the protest of the moral

life against an Art that was free of morals, — I do not say, void

of morals, but free. Indeed, we must study Savonarola's will if we would

understand in Michelangelo himself what was due to Savonarola's

influence.

But this was not all. You

must imagine Michelangelo as a man who in his inmost heart and mind

could never think in any other than a Christian way. He not only felt

as a Christian; he conceived the order of the World in mighty pictures,

in the Christian sense. Imagine him placed in the midst of that time,

when the Christian conceptions had, as it were, become objectified and

could thus slide so easily into the realms of Art. Such was the world

in which he lived. But he experienced withal the Northern protest of the

Reformation, which spread with comparative speed, even to Italy; and he

also witnessed the great and revolutionary change which was accomplished

from the Catholic side as a counter-Reformation, against the Reformation.

He experienced the Rome of his time, — a time whose moral level

may not have been high, but in which there were free and independent

spirits, none the less, who were decidedly agreed to give a new form

to Catholicism. They did not want to go so far as Savonarola, nor did they

want it to assume the form which afterwards came forth in the Reformation.

They wanted to change and recreate Catholicism by continuous progress

and development. Then the Reformation burst in like another edition,

so to speak, of the Savonarola protest. Rome was seized with anxiety

and fear, and they parted from what had pulsated through their former

life. Michelangelo among others had built his hopes on such ideas as

were concentrated, for example, in Vittoria Colonna, hoping to permeate

with high ethical principles what had reached so great a height in Art.

With a Catholicism morally recreated and renewed, they hoped to permeate

the world once more. Now, however, there arose the great Roman powers,

the strong Catholic ideas, the Jesuitical principle, and Paul IV became

the Pope. What Michelangelo was now to witness must have been terrible

for him, for he saw the seeds of an absolute break with what had still

been known to him as Christianity. It was the beginning of Jesuitical

Christianity. And so he entered on the twilight of his life.

Michelangelo, as I said,

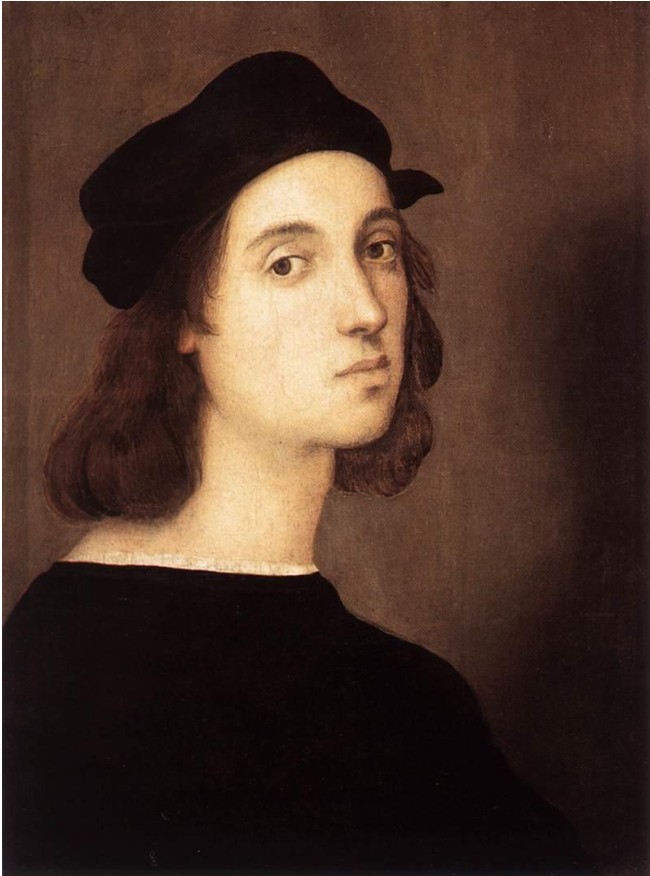

had carried Florence into Rome. With Raphael once again it was different.

Of Raphael we may say, he carried Urbino — East-Central Italy

to Rome. Here we come to that strange magic atmosphere whose presence

we feel when we contemplate the minor artists of that region whence

Raphael grew forth. Consider the creations of these artists — the

sweet and tender faces, the characteristic postures of the feet, the

attitude of the figures. We might describe it thus: Here there arose

artistically somewhat later what had arisen earlier in a moralising

and ascetic sphere in Francis of Assisi. It enters here into artistic

feeling and creation, and leaves a strangely magic atmosphere —

this tenderness in contemplating

man and Nature. In Raphael it is a native quality, and he continues

to express it through his life. This is the feeling which he carries

into Rome; it flows from his creations into our hearts and minds if

we transplant ourselves into the character they once possessed, for

as pictures they have to a great extent been spoilt.

What Raphael thus bears

within his soul, having evolved in the lonely country of Urbino, stnads,

as it were, alone within the time; and yet taking its start from Raphael,

it spread far and wide into the civilisation of mankind. It is as though

Raphael with this element were carried everywhere upon the waves of

time, and wheresoever he goes he makes it felt — this truly artistic

expression of the Christian feeling. This element is everywhere poured

out over the influence of Raphael.

Summing up, therefore, we may

say: Leonardo lives in the midst of a large and universal understanding.

He strikes us, stings us, as it were, into awakeness with his keen

World-understanding. Michelangelo lives in the policical understanding of

his time; this becomes the dominant impulse of his feeling. Raphael,

on the other hand, remaining more or less untouched by all these things,

is borne, as it were, upon the waves of time, and bears into the evolution

of the ages a well-nigh inexpressible quality of Christian Art. This,

then, distinguishes and at once unites the three great masters of the

Renaissance; they represent three elements of the Renaissance feeling,

as it appears to us historically.

Let us now give ourselves up

to the impressions of Leonardo's works. We will first show some of his

drawings, which reveal how he creates his forms out of that keen

understanding of Nature which I sought to characterise just now.

Thereafter,

not quite in the historic order, we shall show those of his pictures

which have the character of portraits. Only then will we go on to his

chief creation, the “Last Supper,” Finally, we shall return

and show him once more at his real starting-point. The first picture

is a well-known Self-portrait.

1. Leonardo da Vinci: Portrait of himself. (Milan.)

This, then, is one of Leonardo's

portraits. There follows the other one, still better known.

2. Leonardo da Vinci: Portrait of himself. (Turin.)

3. Verrocchio and Leonardo: Baptism of Christ. (Uffizi. Florence.)

Here we have a picture from

an early period of his development, showing how Leonardo grew out of

the School of Verrocchio. Tradition has it that the finely elaborated

landscape round this figure here was painted by Leonardo in the School

of Verrocchio, and that Verrocchio, seeing what Leonardo could achieve,

laid down his bruth and would paint no more.

4. Leonardo: Studies. (Windsor.)

Here, again, you see how

Leonardo drew — how he tried, even to the point of caricature,

to extract the characteristic features by dint of studious contemplation,

as I described just now.

We need not imagine that

he stood alone in things like this; they had, indeed, been done by others

in his time. Leonardo only stands out through his extraordinary genius,

but it was altogether a quest of the time — this search for the

strong characteristic features, as against what had come forth in earlier

times from higher vision and had grown a mere tradition. It was

characteristic

of that time to seek for what appears directly to external vision, and

thus bring out with emphasis whatever in the outward features of a being

is most significant of individual character.

5. Death: An Allegory. (Oxford.)

Far more important than

the subject-matter, the point was to study and portray with precision

the positions of the bones and so forth.

6. Warriors.

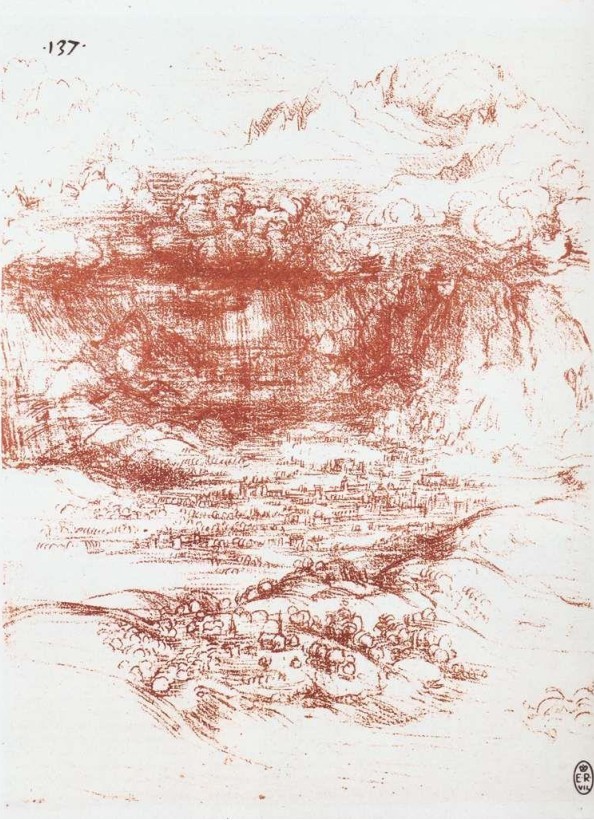

7. Landscape. (Windsor.)

This is the portrayal of

a thunderstorm.

8. Portrait of a Woman. (Vienna.)

The two pictures we now

show are not attributed to him with certainty, nor are some others which

we shall see presently, but they bear the character of Leonardo and

are therefore not without connection.

9. La Belle Ferronniere. (Louvre. Paris.)

10. Mona Lisa. (Louvre. Paris.)

In this famous picture we

see the other aspect of Leonardo, where we might say he seeks to attain

the very opposite pole from what was illustrated in the former sketches.

There he tried to discover and bring out with emphasis the individual

and characteristic in all details. People will often not believe that

an artist who can create such a work as the Mona Lisa has any need of

going in the other direction to the point of caricature. I have, however,

often drawn attention to this fact. Think of the inherently natural

impulse whereby our friend the Poet, Christian Morgenstern, went from

his sublime, serene creations to the humorous poems with which we are

familiar, where he seeks the very extremes of caricature. There is this

inner connection in the artist's soul. If he desires to create a work

so inwardly complete, harmonious, serene as this, he often has to seek

the faculties he needs for such creation by emphasising characteristic

individual features even to the point of caricature.

11. Madonna Litta. (St. Petersburg.)

These pictures, which, as

I said, are not in historic order, represent Leonardo in the quality

of an artist seeking for inner clarity, completeness and perfection.

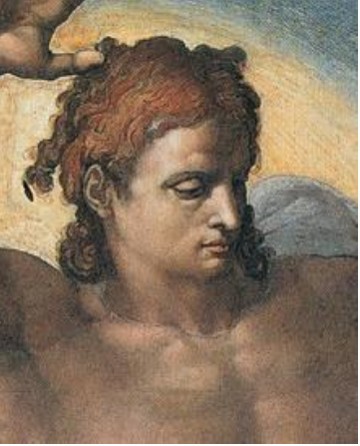

12. Dionysos – Bacchus, heavily painted over. (Louvre. Paris.)

Here is the Dionysos figure,

the God Dionysos. You will find indications on these matters in various

other lectures. The painting is based on proven designs and sketches of

Leonardo da Vinci. However, it is believed that it was carried out by an

unknown student from the workshop of Leonardo and between 1683 and 1693

it was modified and painted to represent Bacchus.

13. St. John the Baptist. (Louvre. Paris.)

15. Madonna of the Grotto. (Paris.)

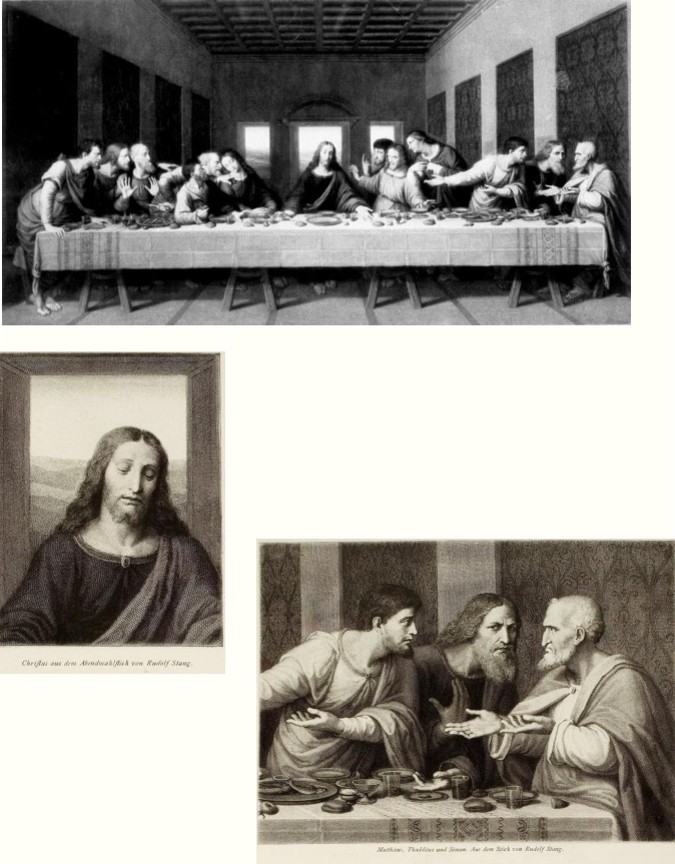

16. Last Supper. (Sta. Maria della Grazie. Milan.)

We now come to the Last

Supper — which he created, it is true, at an earlier time, and

worked upon during a long period. We have often spoken of it. We know

what an essential progress in the artistic power of expression is visible

in this picture as against the earlier pictures of the Last Supper by

Ghirlandajo and others. Observe the life in this picture; see how strongly

the individual characters come out in spite of the powerful unity of

composition. This is the new thing in Leonardo. The adaptation of the

strong individual characters to the composition as a whole is truly

wonderful. At the same time each of the four groups of disciples becomes

a triad complete and self-contained; and, again, each of these triads

is marvellously placed into the whole. The colour and lighting are inexpressibly

beautiful. I spoke once before of the part of the colouring in this

composition. Here we look deep into the mysterious creative powers of

Leonardo. If we try to feel the colours of the picture as a whole, we

feel they are distributed in such a way as to supplement one another,

— not actually as complementary colours, but in a similar way,

— so much so that when we look at the whole picture at once, we

have pure light — the colours together are pure light. Such is

the colouring in this picture.

17. Head of Christ. (Study for the Last Supper.) (Brera. Milan)

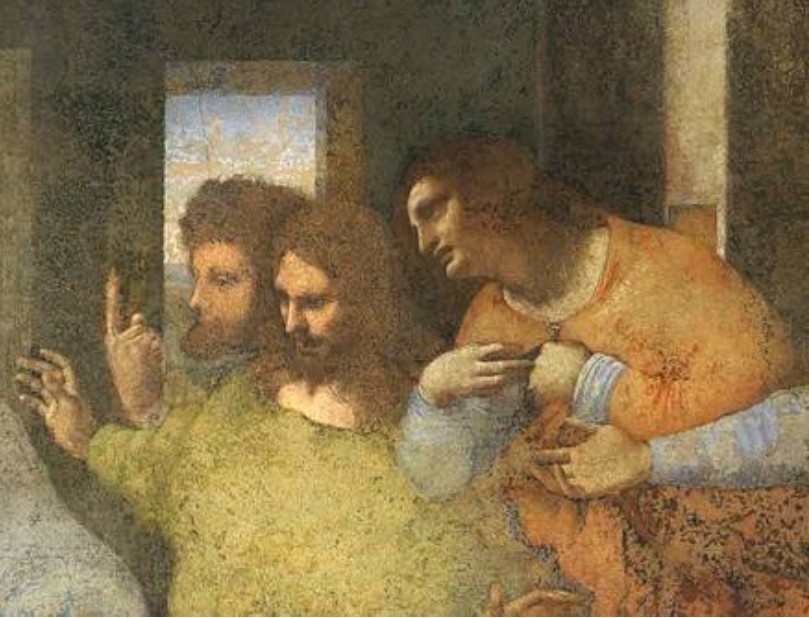

We now come to the details

of the picture. This is generally considered to be an earlier attempt

at the Head of Christ. These reproductions are familiar.

18. Group of Disciples for the Last Supper.

These reproductions of the single figures are in Weimar.

19. Group of Disciples. (Weimar.)

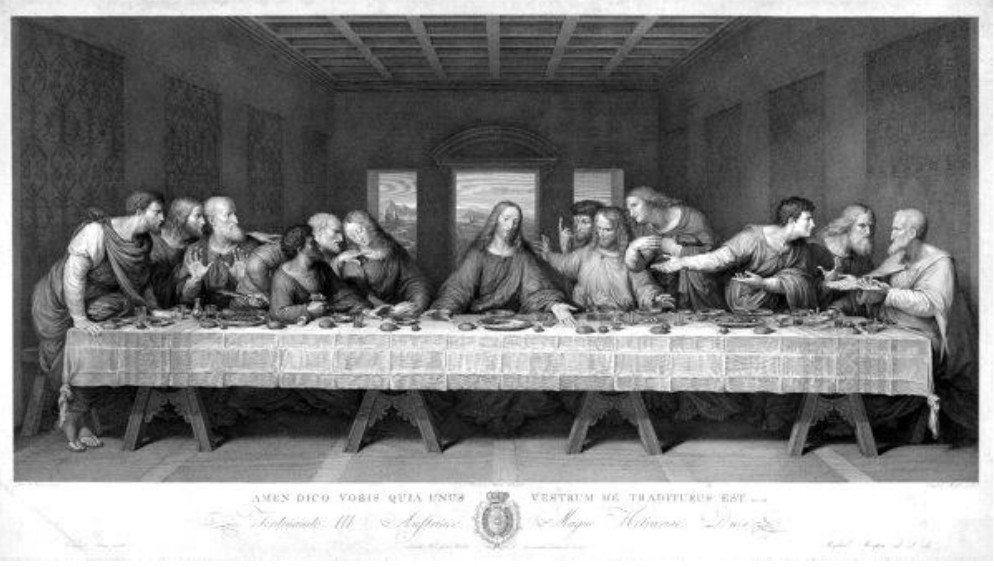

20. Last Supper. (Engraving.)

This is Morghan's engraving,

from which we gain a more accurate conception of the composition than

from the present picture at Milan, which is so largely ruined. You are,

of course, familiar with the fate of this picture, of which we have

so often spoken.

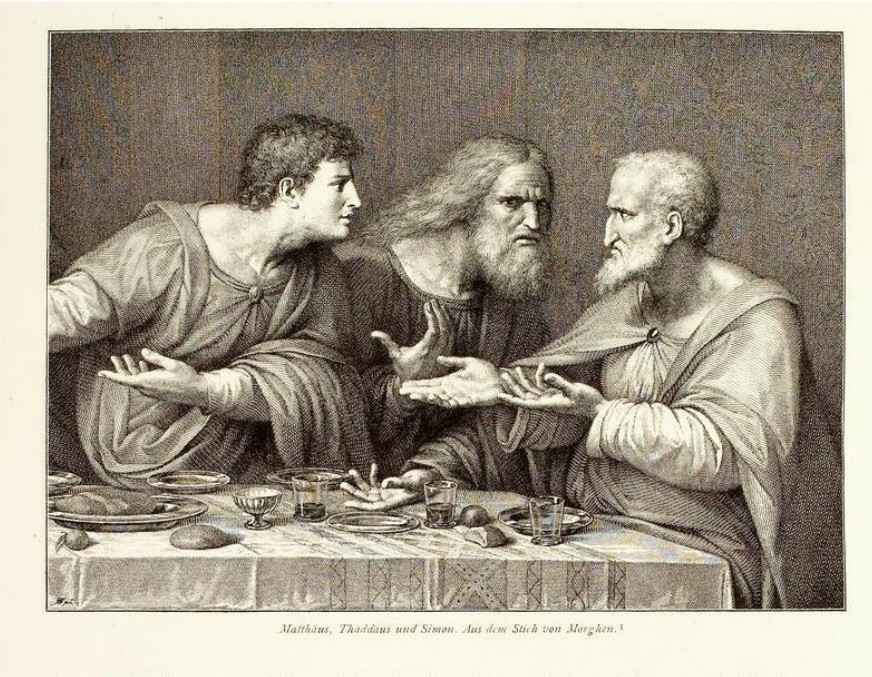

21. Rudolf Stang, The Last Supper. Engraving after Leonardo, completed in 1887.

This is a very recent

engraving, — a reproduction which reveals the most minute study.

It is frequently admired and yet, perhaps, for one who loves the original

as a work of art, it leads too far afield into a sphere of minute and

detailed drawing. Still we may recognise in this an independent artistic

achievement of considerable beauty.

22. St. Jerome. (Vatican. Rome.)

23. Annunciation. (Uffizi. Florence.)

24. Middle group of “Battle of Anghiari”. (Engraving by Gerard Edelinck after the Cretaceous-copy of Peter Paul Rubens.)

Here we have a fragment

of the battle picture projected by Leonardo, which I mentioned a short

while ago.

We will now go on to

Michelangelo.

Considering Leonardo once again, you will see there is something in

him which comes out especially when, instead of taking the chronological

order, which is in any case a little uncertain, we take his work in

groups, as we have done just now. Then we see clearly what different

streams are living in him. The one, which comes out especially in his

Last Supper, aims at a peculiar quality of composition combined with

an intense delineation of character. It stands apart and alongside of

that other tendency in which he does not seek this kind of composition.

This other _stream we find expressed in the pictures in the Louvre,

and at St, Petersburg and London, which we showed before the Last Supper.

It might have come forth at any time; one feels it is almost by chance

that the pictures of this kind do not exist from every period in his

life. That which comes to expression in these pictures is in no way

reminiscent of the peculiar composition in the Last Supper, but aims

at a serene composition while seeking to express individual character

to a moderate extent.

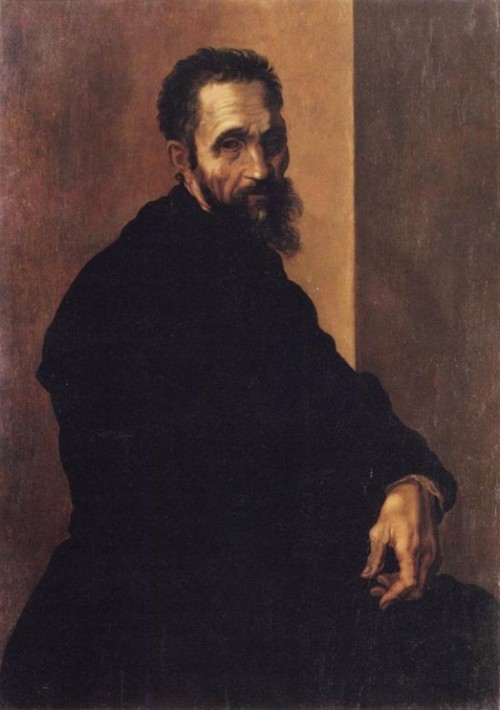

We now come to Michelangelo.

To begin with, his portrait of himself.

25. Michelangelo: Portrait of himself.

26. Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs. (Bas-Relief.) (Casa Buonarotti. Florence.)

Here we have Michelangelo

before he reached his independence, working in Florence, perhaps under

the influence of Signorelli and others, still, in fact, a pupil.

27. Madonna of the Staircase. (Casa Buonarotti. Florence.)

28. Bacchus. (Museo Nazionale. Florence. )

29. Madonna. (Bas-Relief.) (Museo Nazionale. Florence.)

And now we think of Michelangelo

moving to Rome for the first time, under all the influences which I

described just now.

30. Madonna. (Cathedral. Bruges.)

Look at this picture and

then at the following one; compare the feeling in the two.

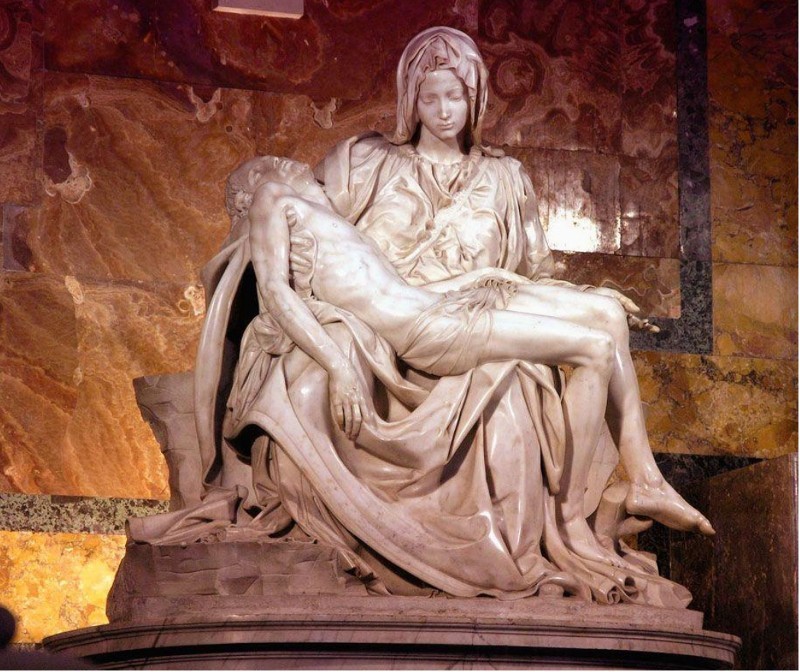

31. Pieta. (St. Peter's. Rome.)

Look at this work. Undoubtedly

it is created under the feeling of his coming to Rome. A more or less

tragic element, a certain sublime pessimism pervades it. Let us return

once more to the former one, and you will see the two creations are

very similar in their artistic character. They express the same shade

of feeling in Michelangelo. We now return once more to the Pieta.

People who feel the story

more than the artistic quality as such have often said that the Madonna,

for the situation in which she is here portrayed, is far too young.

This arose out of a belief which was still absolutely natural in that

time and lived in the soul of Michelangelo himself: — the belief

that owing to her virgin nature the Madonna never assumed the features of

old age.

32. David. (Academy. Florence.)

Here you have the work of

which we spoke before. The figure strikes us most of all by its colossal

quality, not in the external sense, but a quality mysteriously hidden

in its whole artistic treatment.

33. The Holy Family. (Uffizi. Florence.)

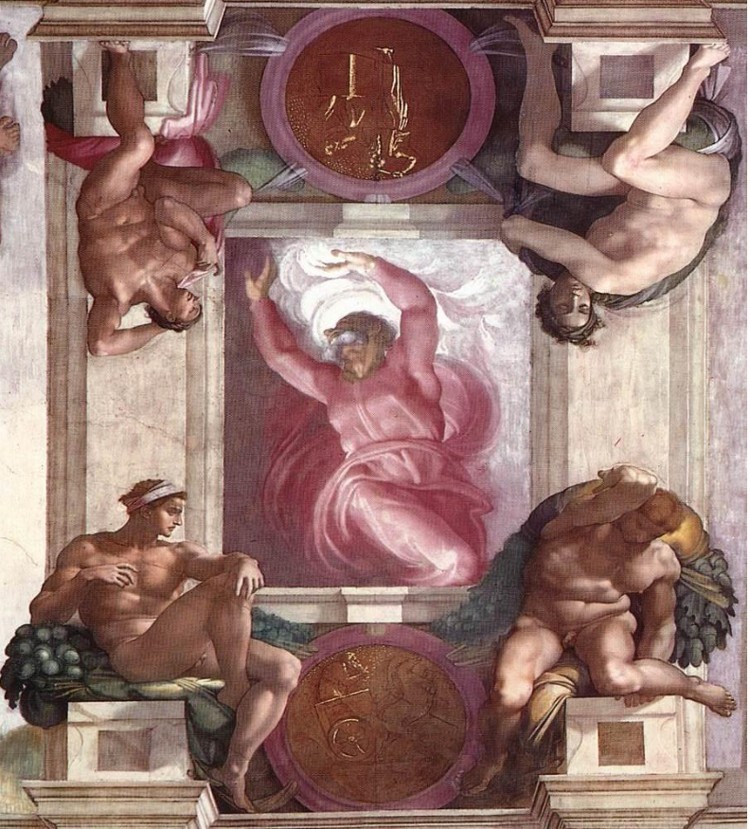

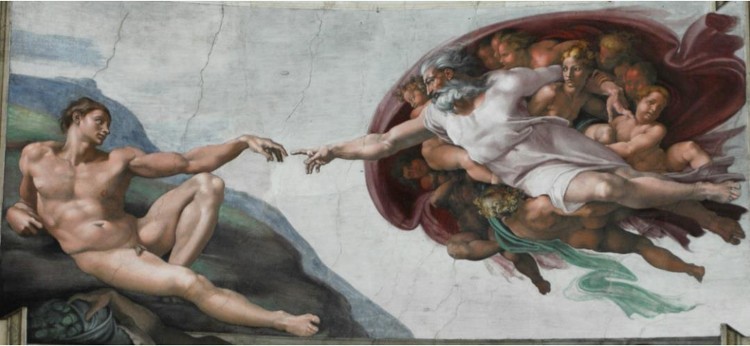

34. Separation of Light from Darkness. (Sistine Chapel. Rome.)

We now come to the Sistine

Chapel. To begin with, we have the Creation of the World, — the

first stage, which we might describe as the creation of Light out of

the darkness of night.

35. Creation of Sun, Moon and Earth. (Sistine Chapel. Rome.)

This picture bears witness

to a tradition still living at that time as regards the creation of

the World. It was that Jehovah created, in a sense, as the successor

of an earlier Creator, whom He overcame, or transcended, and who now

departed. The harmony of the net World-creation with the old which it

transcended is clearly shown in this picture. Truly, we may say, such

ideas as are expressed in this picture have vanished absolutely; they

are no longer present.

36. Creation of the Animals. (Sistine Chapel. Rome.)

This, then, is the creation

of that which went before mankind.

37. Creation of Adam.

Here we find the creation

of man. There follows the creation of Eve.

38. Creation of Eve.

39. The Fall and Expulsion from Paradise.

We now move more and more

away from the theme of World-creation into the theme of History —

the further evolution of the human race. This is the fall into sin.

40. The Erythrean Sibyl.

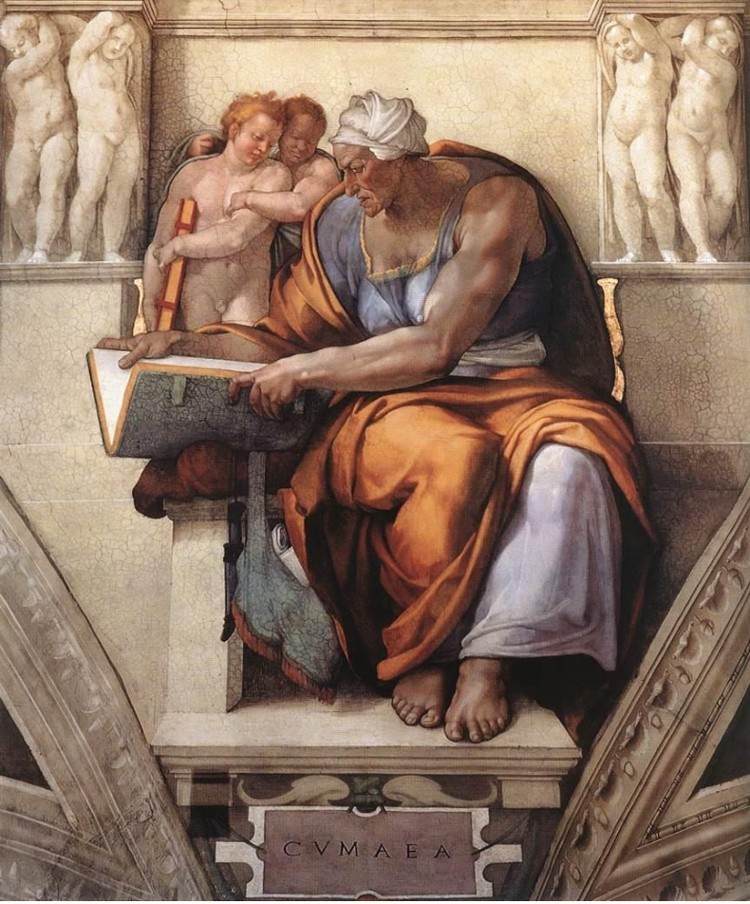

We come to the Sibyls, of

whom I have spoken in a former lecture. They represent the one

supersensible

element in the evolution of man, which is contrasted with the other,

the prophetic quality. We shall see the latter presently in the series

of the Prophets. Here we have the Sibylline element. In my cycle of

lectures given at Leipzig, on “Christ and the Spiritual World,”

you will find the fuller description of its relation to the prophetic.

That Michelangelo included these things at all, in his series of pictures,

proves how closely he connected the earthly life with the supersensible

— the spiritual. See now the succession of the Sibyls; observe

how a real individual life is poured out into each one: in every detail,

each one brings to expression a quite specific visionary character of

her own.

41. The Cumean Sibyl.

42. The Delphic Sibyl.

42. The Delphic Sibyl. (Detail)

Observe the position of

the hand. It is no mere chance. Observe the look in her eyes, coming

forth out of an elemental life; you will divine many things which we

cannot express in words, for that would make the thing too abstract,

— but they lie hidden in the artistic treatment.

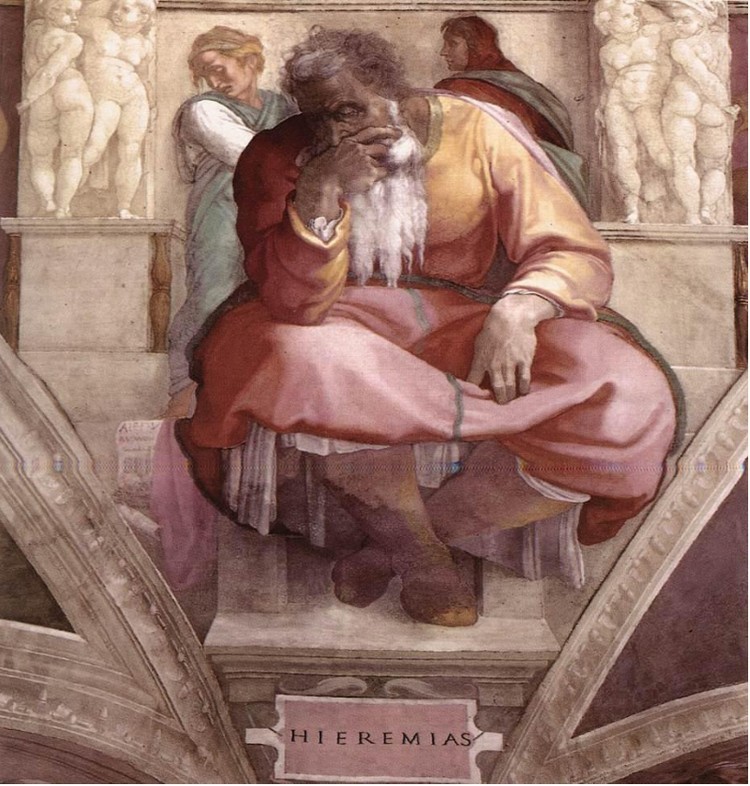

43. The Lybian Sibyl.

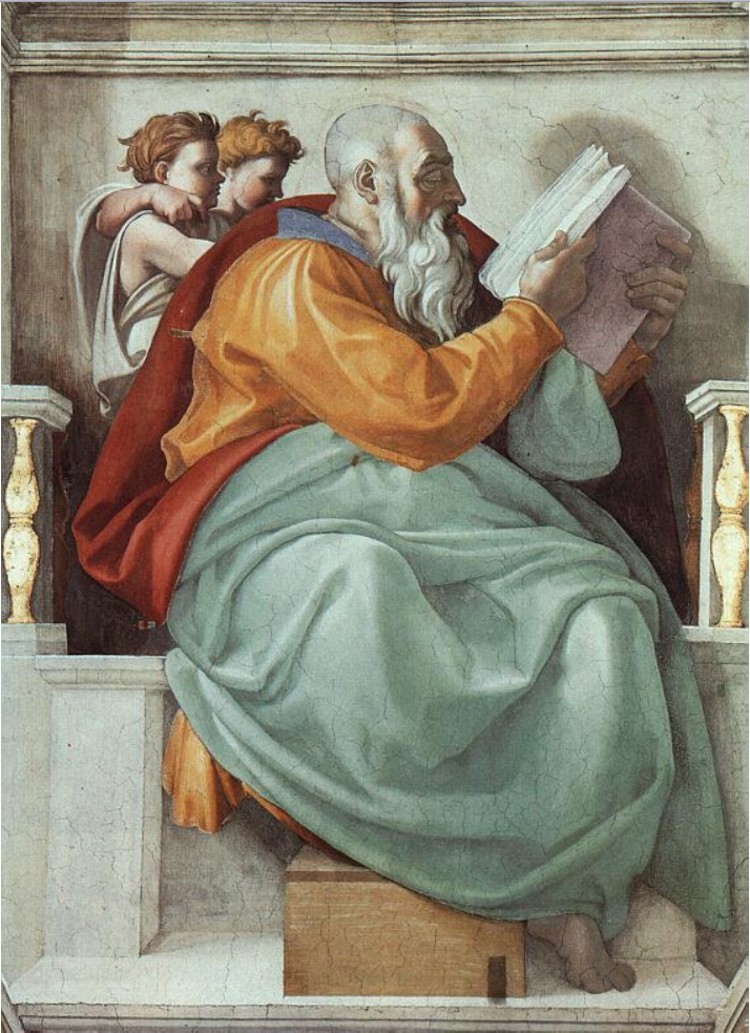

And now we come to the Prophets.

44. Zachariah.

45. Jeremiah.

45. Joel.

47. Ezekial.

48. Isaiah.

49. Jonah.

50. Daniel.

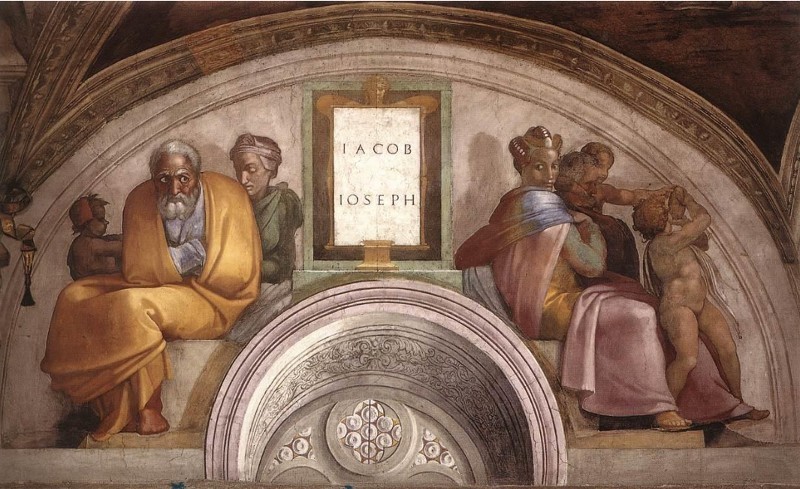

51. The Jacob Group.

These are examples of his

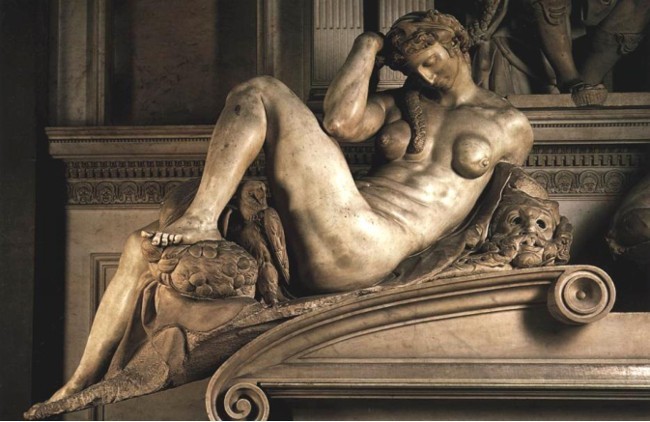

scenes from the Old Testament.

52. Jesse and Solomon Group.

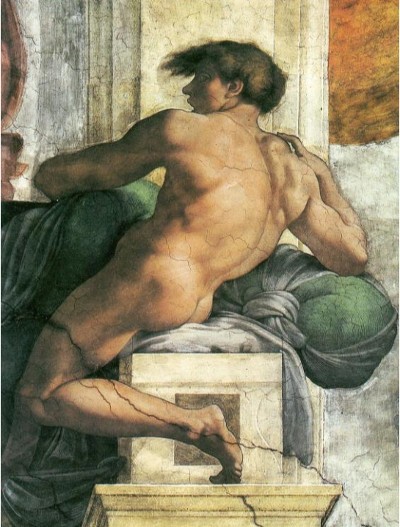

53. Atlas Figures. (Over the Persian Sibyl and Daniel.)

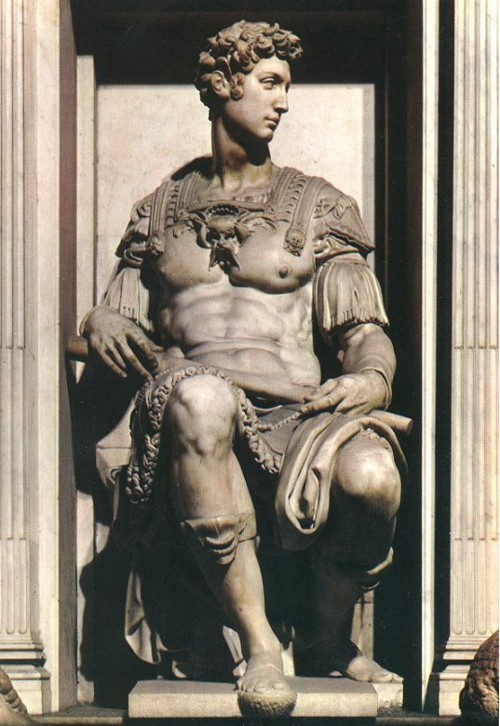

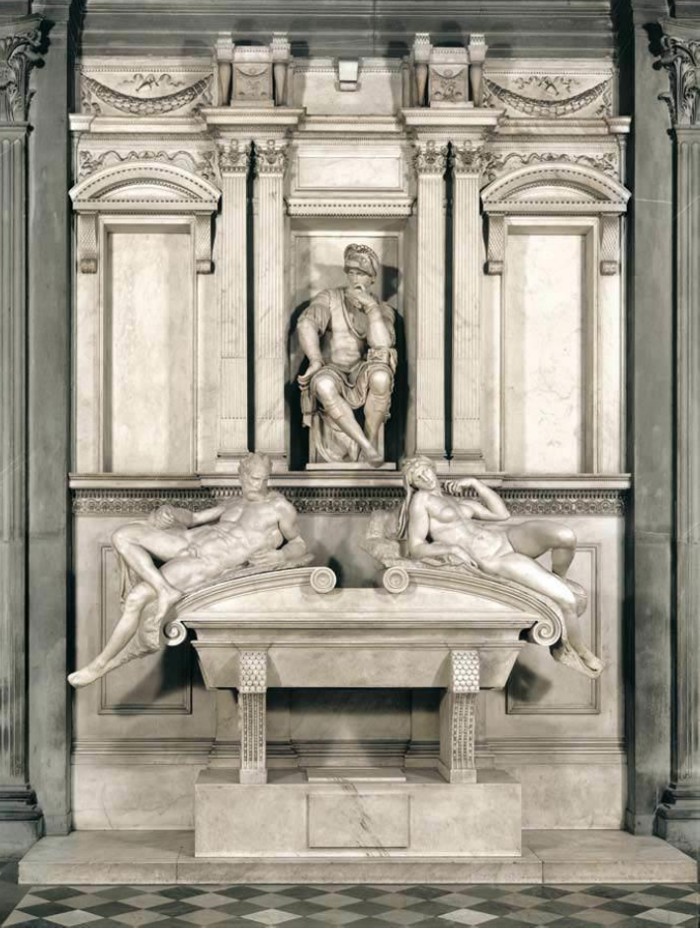

Here we come to his later

period in Florence: to the Medicis and the Chapel at which he had to

work for the Medicis under conditions that I described before. I have

spoken of these tombs of Juliano and Lorenzo in a lecture which I believe

has also been printed.

54. Tomb of Lorenzo. (Medici Chapel. Florence.)

55. Day. (Detail from the Tomb of Lorenzo.)

56. Night. (Detail from the Tomb of Lorenzo.)

57. Tomb of Lorenzo. (The central figure.)

This is the second tomb,

with the figures of Morning and Evening.

58. Tomb of Giuliano. (Medici Chapel. Florence.)

59. Evening. (Detail from the Tomb of Giuliano.)

60. Morning. (Detail from the Tomb of Giuliano.)

61. Tomb of Lorenzo. (The central figure.)

62. Madonna. (San Lorenzo. Florence.)

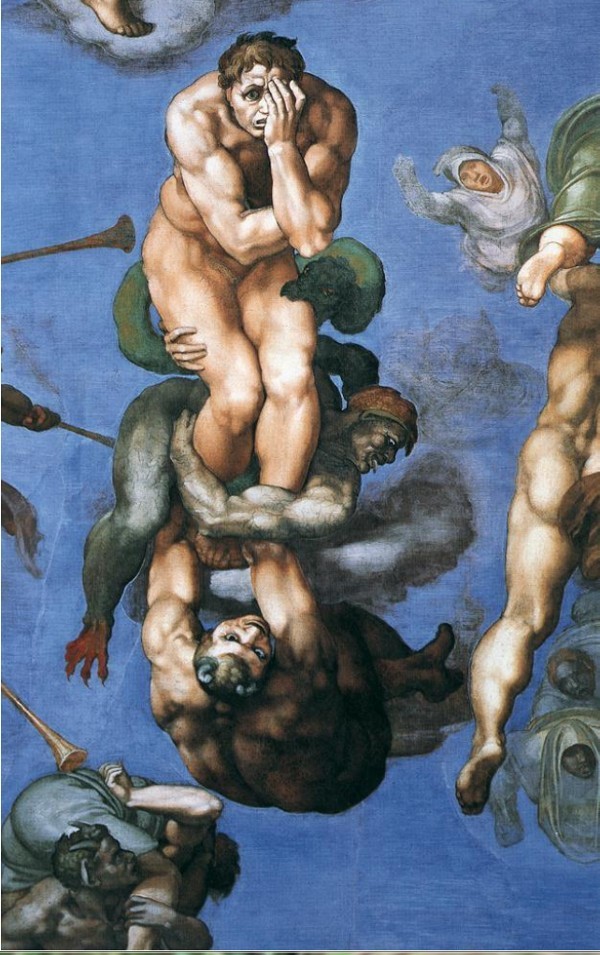

63. The Last Judgment. (Sistena Chapel. Roma.)

Once again we accompany

Michelangelo to Rome, where he creates, once more by comman of the Pope,

the Last Judgment — the altar-piece for the Sistine Chapel. The

greatness of this piece lies in the characterisation, the universal

significance of the characters. Consider in this picture all that is

destined, as it were, for Heaven, all that is destined for Hell, and

Christ in the centre, as the cosmic Judge. You will see how Michelangelo

sought to harmonise this cosmic scene. Majestically as it was conceived,

with an individual and human feeling. Hermann Grimm drew the head of

Christ from the immediate vicinity, and it proved to be very similar

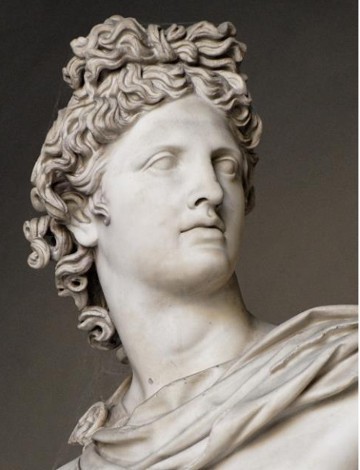

to the head of the Apollo of Belvedere. We will now show some of the

details.

64. Figure of Christ. (Detail from the Last Judgment.)

65. Head of Christ. (Detail from the Last Judgment. Sistine Chapel.)

66. Head of Apollo Belvedere. (Rome, Vatican Greek sculpture))

67. The Barque of Charon. (Detail from the Last Judgment.)

and another detail, the

group above the boat:

68. Group of the Damned. (Sistine Chapel – Rome, Vatican.)

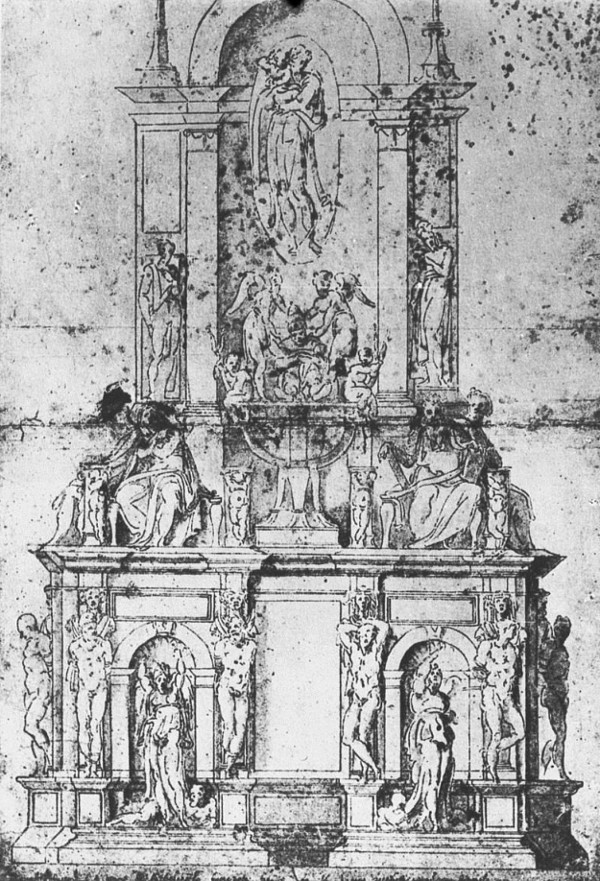

69. Design for the grave of 1513.. (Albertine. Vienna.)

And now, though in time

it belongs to a somewhat earlier period, we give what Michelangelo created

for the monument of Pope Julius; for, in fact, this was never finished,

and Michelangelo was working at it in the very latest period of his

life and finished portions of it.

70. Moses. (St. Peter in Chains. Rome.)

It is significant that Pope

Julius II, whose character undoubtedly contained a certain greatness,

called for this monument to be erected to his efforts. It was to have

included a whole series of figures, perhaps thirty in number. It was

never completed, but there remained this, the greatest figure in connection

with it — Michelangelo's famous figure of Moses, of which we have

often spoken, — and the two figures now following:

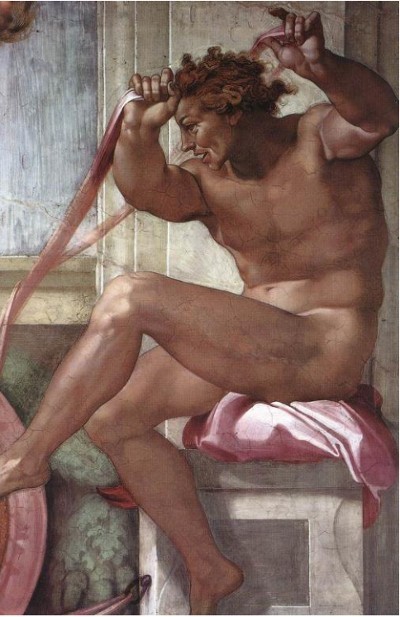

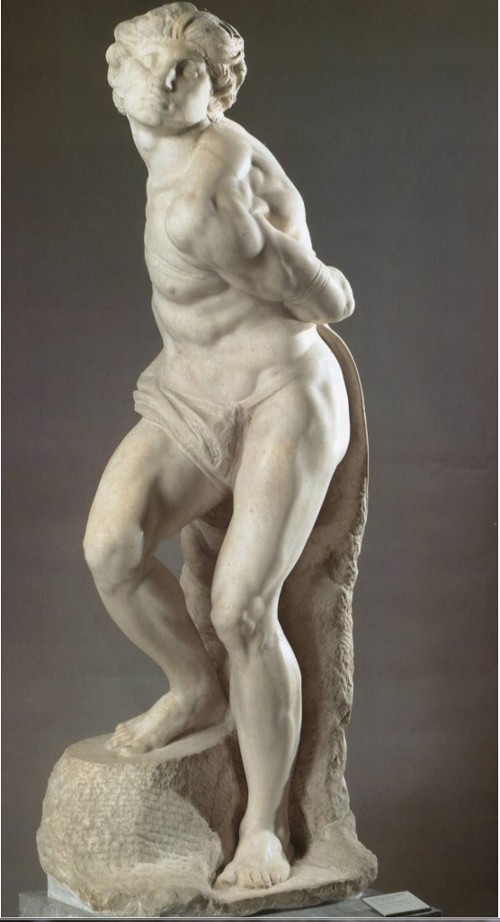

70a. The Dying Slave. (Louvre. Paris.)

70b. The Fettered Slave. (Louvre. Paris.)

70c. Pieta (burial). (Cathedral. Florence. )

This was completed in the

very latest period of his life. It is hard to say exhaustively how it

arose. One thing is certain: the group expresses an idea which Michelangelo

carried with him throughout his life. Whether there was another group

which has somehow been lost, in which he treated this scene at a very

early stage in his career, or whether it was the same block at which

he worked again, remodelling it at the end of his life, it is hard to

say. But we see it here as his last work. Not only is it the one which

he completed when he was a very old man; it corresponds to an artistic

idea which he carried throughout his long life, and is connected far

more deeply than one imagines with the fundamental feeling of his soul.

True, he could not have created it thus at every phase of his life.

It would always have turned out a little differently; it would always

have reproduced the basic mood of his soul in a somewhat different way.

But the deep and pure Christian feeling that lives in Michelangelo comes

to expression especially in this particular relationship of Christ to

the Mother, in this scene of the entombment. Again and again the idea

of the Mystery of Golgotha arises in the soul of Michelangelo in this

way: — He feels that with the Mystery of Golgotha a deed of Heavenly

Love took place, of an intensity that will hover for ever before the

eyes of man as a sublime ideal, but that can never be attained by man

even in the remotest degree, and must therefore inspire with a tragic

mood him who beholds these World-events.

And now imagine, with this

idea living in his soul, Michelangelo saw Rome becoming Jesuitical.

With this idea in his soul, he underwent all the feelings of which I

spoke; and whatever he saw in the world, he measured in relation to

this standard. Truly, he underwent much in his long life. While he was

creating his earliest artistic works in Florence, the Pope in Rome was

Alexander VI, the Borgia. Then he was summoned to Rome, and painted

the Creation of the World for Pope Julius. We see the dominion of the

Gorgias in Rome replaced by Pope Julius, and then by the Medici, Leo

X. In this connection we must realise that Pope Julius II, although

he worked with poison, murder, slander, etc., was none the less in earnest

about Christian Art. Pope Julius, who replaced the political Borgia

princes, strove for the Papal See in order to make it great through

spiritual life. Although he was a man of war, nevertheless, in his inmost

soul, even as a fighter, he only thought of himself as in the service

of spiritual Rome. Of Julius II we must not fail to realise that he

was a man of spiritual aims, thoroughly in earnest with all that lay

in his impulse to re-erect the Church of St. Peter, and, indeed, with

all that he achieved for Art. He was selflessly in earnest about these

things. It may sot strange to say this of a man who in carrying out

his plans made use of poison, murder and the like. Yet such was the

custom of the time in the circles with whose help he realised his plans.

His highest ideal, none the less, was that which he desired to bring

into the world through the great artists. For a spirit like Michelangelo

it is, indeed, profoundly tragical to feel how a perfect good can never

find its realisation in the world, but must always be realised one-sidedly.

Yet, this was not all, for he lived to witness the transition to the

commercial Popes, if we may call them so — those of the house

of Medici, who were, in truth, far more concerned with their own ambitions,

and were fundamentally different in spirit from Julius II and even from

the Borgias. Certainly, these were no better men. We must, however,

judge all these things in relation to the time itself. It is easy nowadays

to feel Pope Alexander VI, or his son Caesar Borgia, or Julius II, as

human atrocities; for today it is permitted to write of them quite

independently and freely, whereas many a later phenomenon cannot yet

be characterised with equal freedom: But we must also realise: —

The sublime works achieved at that time are not without causal

relationship with the characters

of all these Popes, — indeed, many things would certainly not

have come to pass if Savonarola or Luther had occupied the Papal See.

And now we come to Raphael.

71. Raphael. Portrait of himself. (Uffizi. Florence.)

72. Raphael and Perugino. Marriage of the Virgin. (Milan.).

Here is the picture of which

I spoke last time. We will bring it before our souls once more. On the

left we have the same subject treated by Perugino, and on the right

by Raphael. It is the Sposalizio or Marriage of the Virgin. Here you

can see how Raphael grew out of the School of his teacher, Perugino,

and you can recognise the great advance. At the same time, we see in

the picture on the left all that is characteristic of this School on

the level from which Raphael began. See the characteristic faces, their

healthily — as we today call it — sentimental expression.

See the peculiar postures of the feet. A certain characterisation is

attempted; yet it is all enclosed in a certain aura of which I spoke

before, — which appears again in Raphael, transfigured, as it

were, raised into a new form and power of composition. You recognise

here the growth of this power of composition, too. But if you compare

the details, you will find that in Raphael it is grasped more clearly

and yet at the same time it is more gentle, it is not so hard.

73. Raphael. Christ with the Stigmata. (Pinacotec. Brescia.)

74. Dream of a Knight. (National Gallery. London.)

This whole picture is to be

conceived of as a world of dream. It is generally known as the “Dream

of a Knight.”

75. St. George. (Eremitage. St. Petersburg.)

76. Madonna with the Jesus-Children. (Madonna Terranuove. Berlin. )

We will now let work upon

us a number of Raphael's pictures of the Madonna and of the sacred legend.

These — especially the Madonnas — are the works of Raphael

which first carried him out into the world.

77. Madonna Tempi. (Munich.)

78. Madonna in Green. (Vienna.)

79. Madonna of the Goldfinch. (Uffizi. Florence.)

In all these pictures you

still have the old, characteristic postures and attitudes which Raphael

took with him from his home country.

80. The Holy Family: Madonna Canigiani. (Munich.)

81. The Holy Family. (Prado. Madrid.)

82. La Belle Jardiniere. (Louvre. Paris.)

83. Madonna Alba. (Eremitage. St. Petersburg.)

These are the Madonnas which

bear witness to the further development of Raphael. Ile follow him now

into the time when he went to Rome. It is not known historically exactly

when that was. Probability is that he did not simply go there in a given

year, — 1500 is generally assumed — but that he had been

to Rome more than once and gone back again to Florence, and that from

1500 onward he worked in Rome continuously. Now, therefore, we follow

him to Rome and come to those pictures which he painted there for Pope

Julius.

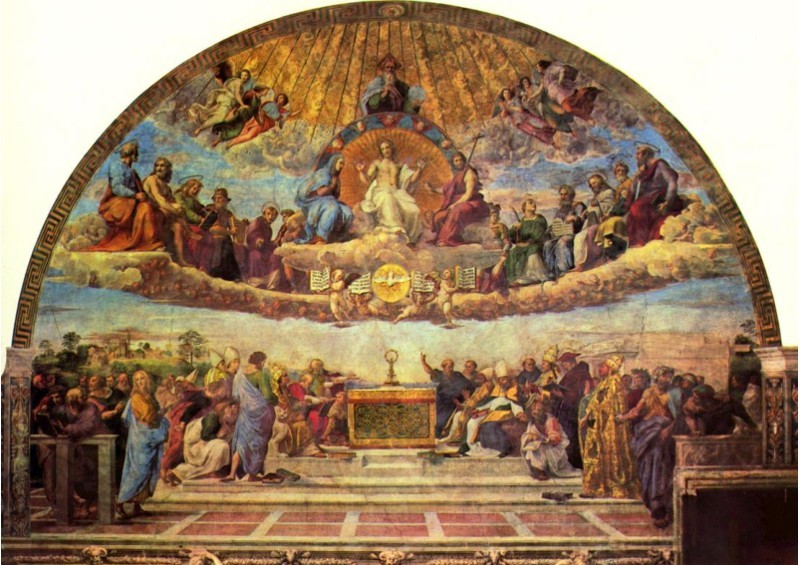

84. Disputa. (Vatican.)

This picture is well-known

to you all, and we, too, have spoken of it in former lectures. Many

preparatory sketches of it exist. In the form in which you see it here,

it was done to the order of the Pope, — the Pope who craved, as

I said just now, to make Rome spiritually great.

We must, however, hold

fast to one point, which is revealed by the fact that some elements

of the motif of this picture appear at a very early stage, even in Perugia,

representing this idea, this scene, or, rather, the motif of it.

84a. The Trinity. (Perugia, S. Severo.)

Thus the idea was already

living at that early stage, and was able to take shape in this remarkable

corner of East-Central Italy.

We must conceive the motif

of the picture as living in the very time itself. Below are the human

beings — theologians, for the most part. These theologians are

well aware that everything which human reason can discover is related

to what St. Thomas Aquinas called the “Praeambula Fidei,”

and must be permeated by what comes down from Spiritual Worlds as real

inspiration, wherein are mingled the attainments of the great Christian

and pre-Christian figures of history, and by means of which alone the

secret of the Trinity is to be understood. This mystery, we must conceive,

bursts down into the midst of the disputations of the theologians below.

We may conceive that this picture is painted out of the will to unite

the Christian life quite fundamentally with Rome — to make Rome

once more the center of Christianity by rebuilding the derelict Church

of St. Peter, according to the desires of Pope Julius. Under the influence

of the Pope, wishing to achieve a new greatness of Christianity centered

in Rome, such ideas are brought together with the fundamental concept;

the secret of the Trinity. This fact explains what I may call, perhaps,

the outer trimmings of the picture. (Even in the architectural elements

which it contains, we see designs which re-occur in St. Peter's.) It

is as though this picture were to proclaim: Now once again the secret

of the Trinity shall be taught to the whole world by Rome. There are

many preliminary sketches showing not only that Raphael only by and

by achieved the final composition, but that this whole way of thinking

about the inspiration, the Idea of the Trinity had been living in him

for a long time. It was certainly not the case that the Pope said:

“Paint me such and such a picture.” He rather said,

“Tell me of the idea that has been living in you for so

long,” and thus together, so to speak, they arrived at the

conception which we now see on the wall of the Segnatura.

85. The School of Athens. (Vatican. Rome.)

Now we come to the picture

which, as you know, is commonly named the School of Athens, chiefly

because the two central figures are supposed to be Plato and Aristotle.

The one thing certain is that they are not. I will not dwell on other

views that have been put forward. I have spoken of this picture, too,

on previous occasions. But they are certainly not Plato and Aristotle.

True, we may recognise in these figures many an ancient philosopher,

but that is not the point of the picture. The real point is, that in

contrast to what is called “Inspiration” Raphael also wished

to portray what man receives through his intelligence when he directs

it to the supersensible and applies it to investigate the causes of

things. The various attitudes which man can then assume are expressed

in the several figures. No doubt Raphael introduced the traditional

figures of ancient philosophers, as, indeed, he always tried to make

use of this or that tradition. But that is not his real point; the point

was to contrast the supersensible Inspiration, the descent of the

super-sensible as an inspiration to man, on the one hand; and on the other

hand the attainment of a knowledge of the world of causes through the

intelligence of man directed to the Supersensible. In this sense, the

two central figures are to be understood as follows: On the one hand

we have a man still in the younger years of life, a man with less

experience

of life, who speaks more as a man who looks around him on the Earth,

there to perceive the causes of things. Beside him is the old, old.

man who has assimilated very much in life, and knows how to apply what

he has seen on Earth to heavenly things. And then there are the other

figures who, partly by meditation, partly by arithmetical, geometrical

or other exercises, or by the study and interpretation of the Gospels

and the sacred writings, seek to discover the causes of things by applying

their human intellect. I have already spoken of these things and I believe

that Lecture, too, has been made accessible. I think if we take the

contrast of the two pictures in this way, we shall not be misled into

nonsensical speculations as to whether this one is Pythagoras or the

other Plato or Aristotle — which speculations are at all events

beside the mark and inartistic. Much ingenuity has been applied in

deciphering the several figures: Nothing could be more superfluous in

relation to these pictures. Rather should we study to observe the

wonderful varieties expressed in the search for all that is attainable

by the intelligence of man.

You may also compare the

two pictures. In this present picture the whole thing is placed in an

architectural setting, whereas in the other, the “Disputa,”

the wide World is the setting. It is the difference between Inspiration

whose house is the great universal edifice and the quest of the human

intelligence which, as you see it here, goes on in an enclosed and human

space.

86. The Three Virtues. (Vatican. Rome.)

We come to what is attainable

in the human sphere, without the latter being influenced out of the

supersensible.

87. Theologia. (Vatican.)

This is like a commentary

to the Disputa — the knowledge of the Divine Mysteries represented

in a more allegorical figure, and leading on to the Disputa.

88. Justice. (Vatican. Rome.)

89. Madonna da Fogligno. (Rome.)

90. Flight of Heliodorus. (Vatican. Rome.)

Here we have a picture taken

from the whole complex which Raphael did for Pope Julius II in order

to inspire the idea that Christianity must gain the victory and all

that resists it must be overcome.

91. Flight of Attila. (Vatican. Rome.)

This is only another aspect

of the same idea.

92. The Liberation of St. Peter. (Vatican. Rome.)

Also belonging to the same

group.

93. The Sibyls. (Ste. Maria della Pace. Rome.)

Raphael's Sibyls. If you

remember those of Michelangelo, you will observe the immense difference.

In the Sibyls of Raphael — I beg you to see it for yourselves

— human figures are portrayed, to represent beings standing within

the cosmos, — Beings into whom the whole cosmos is working. They

themselves are dreaming, as it were, within the cosmos as a very part

of it and have not fully come to consciousness. The various supersensible

Beings, angelic figures between them, bring them the secrets of the

worlds. Thus they are dreamy Beings, living within the universal nexus.

Michelangelo, on the other hand, portrays the human and individual in all

that his Sibyls are dreaming, or evolving out of their

dream-consciousness.

Michelangelo has to create out of the individual, nay, we may even say,

the personal character of each one. These Sibyls of Raphael, on the other

hand, live and move and have their being over and above the individual.

Even inasmuch as they are individual, they live and move in a cosmic

life.

94. The Conversion of St. Paul - Tapestry. (Rome, Vatican.)

95. The Holy Family: Madonna under the oak. (Prado. Madrid.)

96. Sistine Madonna. (Dresden.)

97. The Holy Family. (Louvre. Paris.)

In this room we have the

picture of the Transfiguration. (No picture of room available)

99. The Transfiguration. (Vatican.)

Here is the picture itself.

It is even possible that Raphael himself did not complete it, but left

it unfinished at his death. Christ is soaring heavenward.

To those who say that Raphael

in his latest period painted visionary pictures, we need only reply

by pointing to this figure (the figure of the boy). It is portrayed

in a perfectly real, Occultly realistic sense, how the figure makes

it possible for the scene to become visible to the others. Through what

I would call the mediumistic nature of the unconsciousness of madness,

this figure influences the others, enabling them to behold such a thing

as this.

100. Figure of Christ. (Detail of the above.)

Here we have the figure

of the Christ.

And now, my dear friends,

think of all that Raphael had painted. All that has passed before you

was contained between his twenty-first and his thirty-seventh year,

in which he died. In his twenty-first year he painted the first picture

which we showed — the Marriage of the Virgin — contrasting

it with Perugino's painting. Hermann Grimm worked out in a beautiful

way something that bears eloquent witness to Raphael's free and independent

evolution, proving even outwardly to some extent what I just said before.

Raphael, although he was carried on the waves of time, and learnt, of

course, very much from the world, nevertheless took with him into Rome

the peculiar nature of that Middle-Eastern part of Italy. In spite of

his youth, he created out of his own inmost nature and progressed

undisturbed,

with perfect regularity in his evolution. Hermann Grimm pointed out

that we come to the chief culminating points in Raphael's creative work

if, starting from his twenty-first year, we go forward in successive

periods of four years. From his twenty-first year we have his Sposalizio;

four years later the Entombment, which we have not shown today —

an exceedingly characteristic picture, which, especially when we take

into account the related sketches and everything connected with it,

expresses a certain climax in the work of Raphael. And then, once more,

four years later, we have a climax of creative work in the Camera della

Segnatura in the Vatican. Progressing thus by stages of four years,

we see how Raphael undergoes his evolution. He stands there in the world

with absolute individuality, obeying an impulse connected only with

his incarnation, which impulse he steadily unfolds and places into the

world something that takes its course with perfect regularity, like

the evolution of mankind.

And now consider these three

figures all together, — standing out as a summit in the life of

Art, in the evolution of mankind. It lies in the deep tragedy of human

evolution that this supreme attainment is connected with a succession

of Popes — Alexander VI, Borgia, Julius II, Leo X, — men

who occupy the first position as regards their artistic aims and who

were called upon to play their part in human evolution as rulers in

high places. And yet they were of such a character as to take with them

into these high places the worst extremes which even that age could

nroduce by way of murder, misrepresentation, cruelty and poison. And

yet, undoubtedly — down to the Medici, who always retained their

mercantile spirit, — they were sincere and in earnest where Art

was concerned. Julius II was an extraordinary man, inclined to every

kind of cruelty, never scrupling to use misrepresentation and even poison

as though it were, in a world-historic sense, the best of homely remedies.

Yet it was rightly said of this man that he never made a promise that

he did not keep. And to the artists, above all, he kept his promise

to a high degree; nor did he ever bind or fetter them, so long as they

were able to render him the services which he desired, in the work which

he intended.

Consider, alongside of this

succession of Popes, the great men who created these works — the

three great characters who have passed before our souls today. Think

how in the one, in Leonardo, there lived much that has not yet been

developed further, even today. Think how there lived in Michelangelo

the whole great tragedy of his own time, and of his fatherland, both

in the narrower and in the wider sense. Think how there lived in Raphael

the power to transcend his Age. For while he was most intensely receptive

to all the world around that carried him as on the waves of time,

nevertheless,

he was a self-contained nature. Consider, moreover, how neither Leonardo

nor Michelangelo could carry into their time that which could work upon

it fully. Michelangelo wrestled to bring forth, to express out of the

human individuality itself all that was contained in his time; and yet,

after all, he never created anything which the age was fully able to

receive. Still less could Leonardo do so, for Leonardo bore within his

soul far greater things than his Age could realise. And as to Raphael

— he unfolded a human nature which remained for ever young. He

was predestined, as it were, by providential guidance to evolve such

youthfulness with an intensity which could never grow old. For, in effect,

the time itself, into which all that came forth from his inner impulses

was born, first had to grow young. Only now there comes the time when

men will begin to understand less and less of Raphael. For the time

has grown older than that which Raphael could give to it.

In conclusion, we will show

a few of Raphael's portraits.

101. Pope Julius II. (Uffizi. Florence.)

102. Pope Leo X.

These, then, are the two

Popes who were his patrons.

103. Donna Veleta. (Pitti. Florence.)

104. Balthasar Castiglione. (Louvre. Paris.)

We have come to the end

of our pictures.

In the near future, following

on the tree great masters of the Renaissance, we shall speak of Holbein,

Durer, and the other masters — the parallel phenomena of these

developments in Southern Europe.

Today I wanted especially

to bring before our souls these three masters of the Renaissance. I

have tried to describe a little of what was living in them, and of their

stimulus if, starting from any point of their work, you dwell on the

historic factors which influenced and entered into them. You will perceive

the necessary tragedy of human history, which has to live itself out in

one-sidedness. We can learn much for our judgment of all historic

things, if we study how the world-historic process played into that

Florentine Age whose greatness is identified with Raphael, Michelangelo

and Leonardo. Today especially I fancy no one will regret the time he

spends in dwelling on a historic moment like the year 1505, when

Michelangelo,

Leonardo and Raphael were at the same time in Florence — Raphael

still as a younger man, learning from the others; and the other two

vying with one another, painting battle-pieces, glorifying the deeds

that belonged to political history. Especially at the present moment,

anyone who has vision for the facts of history in all its domains, and

sees the significance of outward political events for the spiritual

life, will profit greatly by the study of that time. Consider what was

working then: — how the artistic life sought and found its place

in the midst of the outer events, and how through these artistic and

external events of the time, the greatest impulses of human evolution

found their way. See how intimately there were interwoven human brutality

and high-mindedness, human tyranny and striving towards freedom. If

you let these things work upon you from whatever aspect, you will not

regret the loss of time, for you will learn a great deal even for your

judgment of this present moment. Above all, you will have cause to rid

yourself of the belief that the greatest words necessarily signify that

the greatest ideas are behind them, or that those who in our days are

speaking most of freedom have any understanding at all of what freedom

is. In other directions, too, much can be gained for the sharpening

of our judgment in this present time, by studying the events which took

place in Florence at the beginning of the 16th century, while under

the immediate impression of Savonarola who had just been put to death.

We see that Florence in the midst of Italy, at a time when Christianity

had assumed a form whereby it slid over on the one hand into the realm of

Art, while on the other hand the moral feelings of mankind made vigorous

protest against it, was a form fundamentally different from that

of Jesuitism which found its way into the political and religious stream

immediately afterwards, and played so great a part in the politics of

the succeeding centuries down to our day.

Of course, it is not proper

at this moment to say any more about these things. Perhaps, however,

some of you will guess for yourselves, if you dwell upon the chapter

of human evolution whose artistic expression we have today let work

upon our |