Lecture IV

Dornach, 15th November, 1916

Continuing our

studies on the great works of Art, we will show some further slides

today, supplementing those that were shown last week. Today I

propose in the main to supplement what I endeavoured to explain

last week, of the connections and contrasts between the

Mid-European, or Northern, and the Southern Art. I tried to show

how the specifically artistic quality is always influenced by the

character of the South or of the North, while, on the other hand,

there were continual interpenetrations of the Southern and

Mid-European impulses, layer upon layer, as it were, so that it is

by no means easy now to see how these things really worked

together. Spiritual scientific investigations will in course of

time have to bring more and more light into these matters.

Today I wish to draw

attention to the contrasts from certain other points of view. You

will remember what I emphasised last time. From underlying impulses

of the Mid-European spiritual life, there arose what we may call

the art of expression — expression of Will and Intelligence

— the power to express the ever-mobile life of the soul. The

soul in movement — that is the goal of the Mid-European

impulse; while the Southern (which was, however, influenced at a

very early stage by the Mid-European) looks more to all that enters

our perceptions from the Divine-spiritual in the Cosmos, which

finds expression in the power of composition, and in features which

transcend the human.

It is a

characteristic abuse of our time to consider Art — even the

plastic Arts — far too much from the mere point of view of

the narrative and subject matter, while appreciating far too little

the specifically artistic qualities. At the same time there is

another equally pernicious error. Art is very frequently severed

nowadays from the general life of culture and civilisation, and

treated as though it were something that lives a life apart. This,

too, is wrong. For we need only have a feeling for the specifically

artistic qualities, for all that works in form and colouring, in

composition and the like — we need only wean ourselves of the

tendency to explain everything symbolically, or in other artificial

ways; we need but feel — before such pictures as Dürer's

‘St. Jerome,’ or ‘Melancholia,’ for

example, — how infinitely deeper is the mysterious ebb and

flow of the masses of light themselves, than any artificial

symbolism we may choose to read into these pictures. Then we shall

recognise that the specifically artistic qualities that come to

expression in the great works of Art, are also living in the whole

general life of civilisation. Out of the common feeling of his time

the artist works into the spheres of form and color and expression.

The time itself works through the soul of the artist. The whole

culture of the age finds expression in the characteristic works of

Art.

We saw last time how

the Mid-European, or Northern element, works its way upwards more

or less independently, while at the same time it grows together

with all that is brought to it through the Church — through

Christianity from the side of Rome. Until the 12th and 13th

centuries we witness the development of a unique artistic life in

Middle Europe, uniting the more Roman or Latin elements with a

strongly individual characterisation of all that is life and

movement in the human soul. We cannot understand what took place

until the 12th and 13th centuries if we merely consider what we

know of the spread of Christianity in the succeeding time. For the

whole spread of Christianity was a very different thing in those

earlier centuries from what it afterwards became. It was only in

later times that the rigidly dogmatic qualities which so repel us,

came into prominence, though, needless to say, there were all

manner of excesses even before the twelfth century. And while in

Middle Europe the systemmatising, formal tendency of Rome was

always felt like a foreign body, still the Christian impulses found

their way most wonderfully into the soul-life of the people —

especially into the more subconscious, feeling elements of the

soul.

This entry of

Christianity into the soul found expression especially in the

sphere of Art, where there was a wrestling for plastic power of

expression.

Here we may point to

a truth which can be characterised in two very simple statements

which are, none the less, very far-reaching. We may ask this

question: To what does Art appeal among the Southern peoples? To

what did it appeal already in antiquity? And elsewhere in the

South, in the period of its decline and in its resurrection from

the early to the late Renaissance? To what does Art appeal in the

more southern regions? It appeals to the fancy and imagination.

This statement is of infinite importance. The appeal is to the life

of the fancy and the imagination, which is present in the souls of

the southern people with a slight, suggestion of a sanguine

temperament in these respects. Thus in the southern regions we see

the Christian ideas entering, above all, into the imaginative life,

and borne by fancy into the realm of Art.

Needless to say, such

a statement must not be pressed too far. I would say, the statement

itself should be artistically understood.

Only so, my dear

friends, could it come about that in the time of the Renaissance

artistic fancy rose to such great heights of creation, while the

moral life, as we showed in a recent lecture, fell to the state

revealed in the attacks of Francis of Assisi, and later of

Savonarola. The situation stands before us when we contrast the

fiery attacks of Savonarola which were all in vain, with the

infinitely rich life of Christian vision and imagination in the

plastic works of Donatello, Michelangelo, Raphael, Leonardo and

many others.

Art in the North

speaks differently and appeals to a different element of soul,

namely, to mind and feeling. Once more, these things must not be

pressed; nevertheless, in such a statement guiding lines are given

for the understanding of whole epochs of History. However we may

believe that Christianity contains a peculiar, morally religious

impulse of the soul, this impulse did not find its way into the

element of fancy and imagination in the Southern culture which

reached such giddy heights in the Renaissance. But in the North,

the centuries until the 12th — nay, the beginning of the

13th — reveal in Art the progressive appeal of Christianity, and

especially the tragic elements of Christianity, to human heart and

feeling. The Art of the Italian Renaissance strives to make the

countenance of Christianity itself as fair as possible — that,

after all, is the essential element in the Renaissance Art: But the

centuries to which I now refer, in Middle Europe, are all devoted

to the striving to realise the Story of the Passion — with all

its tragedy and drama, until the tragic story becomes their very

own in heart and soul.

Down to the

Carolingian period in Middle Europe, Mid-European paganism

continually breaks through into the life of feeling. But in the

centuries from that time onward until the 12th and 13th there

arises out of the very soul of Middle Europe an inherently

Christian Feeling for all human life. And the strange thing is that

from the 13th century onward a certain decline can be observed.

Yet, as I explained last time, even now when another element once

more overwhelms it, there is still the constant striving for the

Mid-European soul to assimilate into its deepest inner life all

things that come to it, so that, after all, there is a continuity

of work and progress in the best souls, from the 11th century on

into the 15th and 16th.

The gradual entry of

Christianity into the life of the people is also recognisable, or,

rather, would be recognisable, if the dramatic representations

which did, indeed, grow more and more significant toward the 13th

century, had been preserved. All that we now bring to light

again — the Christmas and Easter Plays, and Plays of the Three

Wise Men — are of a later date, and are but a faint reflection

of those earlier ones which tended to a more universal presentation

of the Christian world-conception. The Play concerning Anti-Christ,

of the 12th century, which has been found at Tegernsee in Bavaria,

and a later Play on the Ten Virgins, these, too, are but echoes of

Plays that were presented everywhere, dramatising the Biblical

stories and the sacred legends. Out of this life with the Christian

world-conception as a whole, there arose the works of Art which we

shall see again today and which we say last time. There followed

what I might call a slow and silent working towards the deepening

of the soul's life and its artistic power of expression. It finds

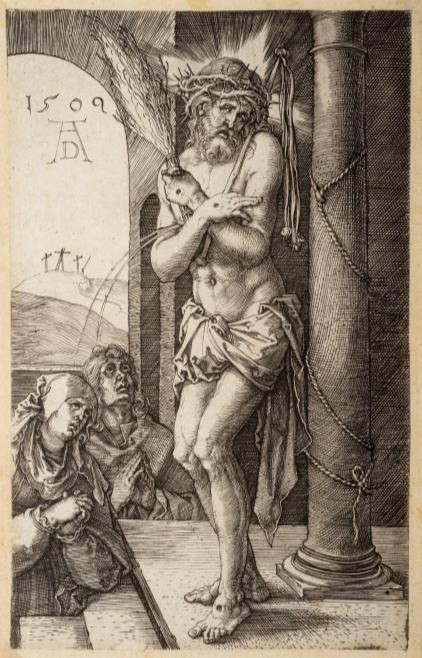

expression wonderfully in Dürer's representations of the

Passion, and notably in the head of Christ Himself as conceived by

Dürer and others. It will be a satisfaction to me if we can

show these pictures, too, on some future occasion; we do not

possess them at present.

If we study the

progress of artistic penetration in pictures of the countenance of

Christ till Dürer's time, and in other things as well, we find

there was really attained in Mid-Europe at that time an astonishing

degree of maturity. It lies inherent in the subtle difference

between the Mid-European and Northern, and the Southern life, which

developed, as it were, the last phases of the Fourth Post-Atlantean

epoch — (albeit the Fifth epoch already shone into the

Renaissance); — the South in its deepest tendencies of

feeling was still expressing the last phases of the Fourth; while

in Mid-Europe and the North the Fifth Post-Atlantean epoch was

preparing. What afterwards became the expression of the individual,

and of all that is mobile in the human soul — the soul in

movement and emotion — all this was working its way up from

unconscious depths.

Here we see the whole

life of the two regions in their essential difference. We need only

bear in mind how much in the Southern Art is due to the fact that

there still existed a living atavistic perception of what plays

from spiritual regions into the realms of sense. For this was,

indeed, preserved in what are known to us of the Byzantine forms of

Art — in all the suggestive forms and figures that have come

down to us. Take, for instance, what works upon us with such

suggestive power in the Art of the Mosaics, and in all that is

connected with the name of Cimabue. Here it is more the Christ

Figure that works upon us. In Middle Europe it is, rather, the life

of Jesus that is presented to us, for the artistic forms are

created directly out of the inner life of the soul.

Superhuman

as is the Byzantine type of Christ, inwardly human is the

Christ type which was afterwards worked out by Dürer.

The Fourth

Post-Atlantean epoch, including the latest flower (in the Italian

Renaissance) has essentially the quality of looking upward to the

superhuman and typical; the superhuman and generic nature

of the soul, setting aside the individually human. The Southern

peoples brought to their Art, in a far higher degree, the ancient,

the generic nature of the soul in its superhuman and divine

quality.

In the Northern Art,

on the other hand, we see the strong decided striving of the

individual, as it works its way upwards out of every single human

soul. The more these things are understood, the more this will be

confirmed.

The southern life

still contains mankind as a whole. Think how intensely an Athenian

was an Athenian, or a Spartan a Spartan, so that Aristotle rightly

called man a “Zoon politicos” — a political animal.

The “political animal” was developed to its greatest

height in Rome, where, we might say, man lived more in the streets

than in his own house; and with his soul-life, also, he lived more

in the life that surrounded him than in the house of his own soul.

Such, truly, was the Southern imagination as it worked in the world

of space. From the very outset men live together, live together as

a whole, and the life of Art itself arises out of this principle.

This is a feature common to all the Southern Art. They decorate the

churches and the public squares; everywhere we see how they reckon

with the fact that the people run gladly together, crowd gladly

into the churches, or in the public squares, drawn thither by their

very temperament and expecting what will there be set before them.

To possess themselves fully, they need this life in the outer

world, this living with the group-soul nature — with all that

is most eminently political — in the right sense of the

word.

All this is different

in Middle Europe. In Middle Europe man lives within himself; seeks

his experiences in his own house and home, even the house of his

soul. And if he is to dedicate himself to the group-nature, his

heart must first be conquered for it, he must in some way be

summoned to it. Many of the underlying impulses of Gothic

architecture will be found to lie in this direction. The buildings

erected by Gothic architecture stand there not because the people

are already running together of their own accord, but, on the

contrary, because they must first call the people, bring them

together, as it were, through mysterious and suggestive influences.

This is expressed in the very forms of the Gothic. The individuals

must first be called to the group-life. And the same thing

lies inherent in the whole treatment of light and darkness which I

described to you the other day. In the elemental surging and

interweaving of the light into the darkness, man finds an element

into which he can enter to free himself from his own separate

existence; albeit he can carry his individual existence, his

individuality with him into this very element, because it is so

akin to the nature of the soul.

In all these things

we find the distinguishing feature of the Northern as against the

Southern Art. Hence the striving — the successful striving

— of the Northern Art to express inwardness of life and soul.

We need only call to mind the portraits, the Madonnas, for

instance, of Van Eyck. These Madonnas — their facial

expression altogether determined by a turning inward of the life of

the human soul — this speaking from an inwardness of soul in

the countenance and gesture — all this, Raphael would never

have painted. Raphael raises what he paints beyond the human; Van

Eyck lifts it into the still more deeply human, so as to seize the

human emotions with his paintings, the human hearts of those who

see them. Once more it is a question of grasping the human soul.

The priesthood until

the 12th and 13th centuries were well aware of these possibilities

of the human soul in Europe. They reckoned with these things. They

worked with the heart and mind of the people. And without a doubt,

much that arose out of this wrestling for artistic powers of

expression, came about through the co-operation of the religious

orders with that inner life and character of the people which we

have here described. We must by all means understand how these more

Northerly qualities of artistic creation are connected with the

protesting folk-soul of the North, rising up in opposition

against the Roman element.

Luther went to Rome.

But he saw nothing of the sublime heights of artistic creation; he

saw only the moral degradation there. And this implies very much.

No doubt he met one or another of the great painters of Rome on the

Square of St. Peter's, but what concern had they for him, these men

who created out of al altogether different mood of soul, something

to which he had no inner relationship. And yet, Luther's very

radical one-sidedness was in another way the product of the same

Mid-European characteristics which, if I may say so, wrestled most

sublimely in the realm of plastic, pictorial expression, and

attained an artistic height that stands, in a certain way, so

magnificently and independently side by side with the Art of the

Italian Renaissance. (We need make no comparisons, for they are

always trivial.)

We will therefore now

show a few more pictures, supplementing those we showed last week.

First we will show some wood-sculptures from the very beginning of

the 13th century. They are at Halberstadt.

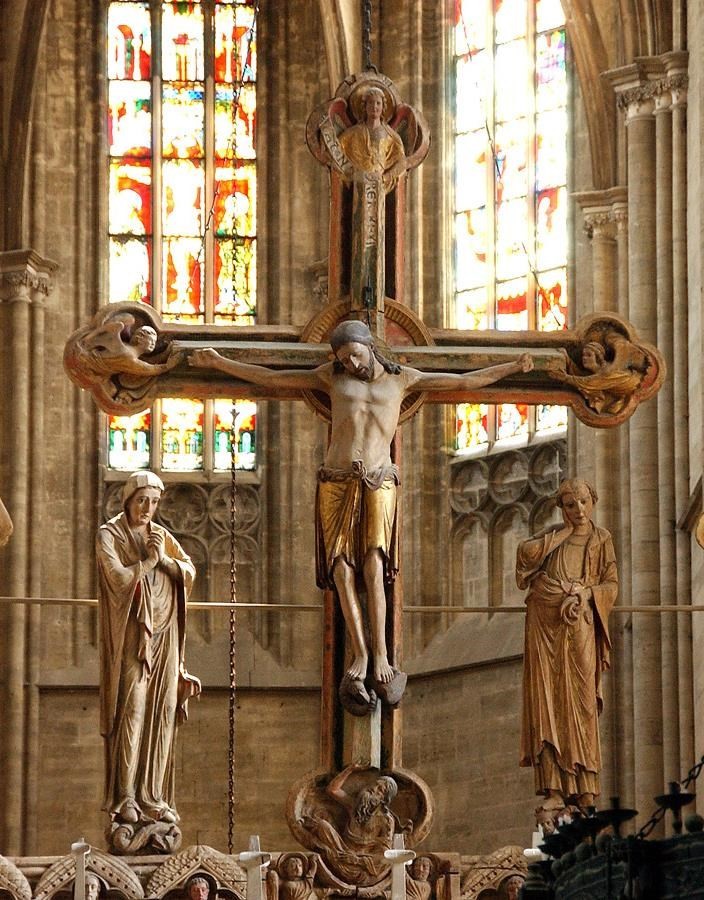

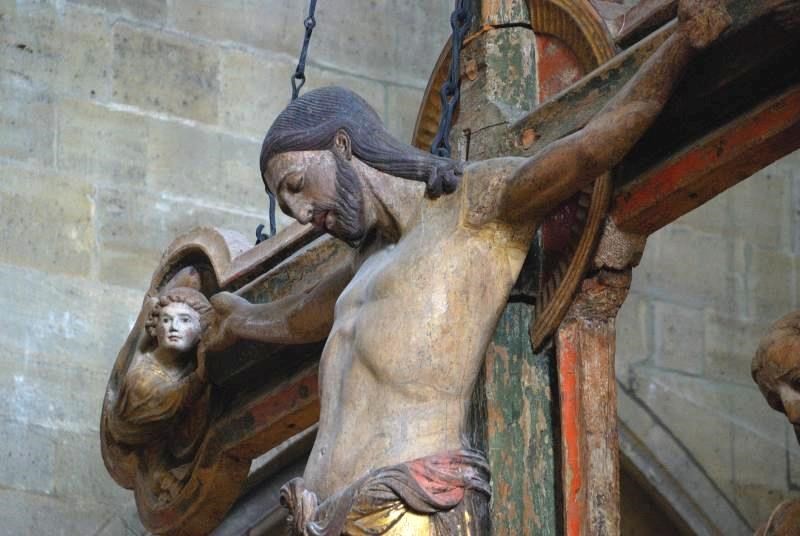

1. Crucifixion Group. (Cathedral. Halberstadt.)

Look at this

Crucifixion Group. I will only say one thing to characterise what

is most important. In this group you can see how deeply the story

of the Passion had found its way into their lives by that time.

There is Mary, there is St. John, and in the center the Christ,

looking down towards her. If you could see the face you would see

an infinite deepening of soul in the expression, an overwhelming

depth. In Mary, if you have a feeling for these things, you will

recognise at once the flowing together of the more Roman, priestly

conception with the Mid-European depth and tenderness of feeling.

Here it is recognisable in a most wonderful way. We shall presently

show the face of Mary in detail.

This group reveals

how they contrived, out of the specifically Mid-European creative

impulse of the soul, to mould the Christianity which had conquered

the Mid-European country. We will now show the detail.

2. Head of Mary. (Detail of the above.)

Wonderfully

characteristic is the expression of the face. The expression in the

Southern Art is such that the eyes look far out into the world; in

the Northern Art the soul, as it were, presses forward into the

look of the eyes from within. Here the two are altogether

interwoven — united with one another. A tenderness of soul in

the expressions hovers gently, wonderfully, over a more Latin,

Roman rounding and perfection of the features.

These things must not

be pressed. But I beg of you to observe in all the following

pictures how very differently the clothing and drapery is treated

in the Mid-European Art and in the Southern. Undoubtedly, such

things must not be pressed too far; yet it is true to say that in

all the Southern Art the drapery rather surrounds and veils the

human form, follows the lines of the form closely, continuing, as

it were, the bodily forms. In the Mid-European Art the treatment of

the drapery is different. It proceeds from the emotion and movement

of the soul. According to the gesture of the hand and the whole

attitude of the figure, the quick, mobile life of soul is continued

into the raiment. The latter adheres less closely to the body. It

does not seek, as in the Southern Art, to veil or to express the

forms of the body. It is, rather, like a continuation of the living

experience of the soul. You will see this more and more distinctly

as we go on into the following centuries.

We have now come to

the famous:

3. Crucifixion Group. (at Wechselburg in Saxony.)

This, too, is in the

wood, and dates from the first third of the 13th century. None the

less, you will see in it a wonderful progression from the former

group whose subject is so similar. Observe the communion of soul

between the Mary and the Christ-Figure. See how the faith in the

Christian world-conception, deeply united with the human soul,

appears in the St. John and in the Mary-Figure, as the power that

overcomes all things. The Christian world-conception had entered

into the souls of these people so as to become an universal

historic conception of all earthly evolution. See how Adam, down

here, receives the Blood of the Redeemer dropping downward from the

Cross. Study the face of Adam, how he is touched by the influence

of Grace which he can now receive inasmuch as he may catch the

Blood of the Redeemer flowing from the Cross. You will realise with

what infinite depths Christianity had found its may into the lives

of these people. It had risen to a universal and truly

Cosmic conception.

Angels carry the

Cross. God the Father descends with the Dove, setting His seal upon

the fact that what He had given to the Earth in His Son gives, at

this moment, the whole Earth its meaning. In this group with all

its artistic perfection we see how deeply Christianity had found

its way into Middle Europe,because they tried again and again to

permeate it with the human heart and feeling, — to permeate

it from within the human soul.

On the other hand, in

the South, it was permeated by fancy and imagination, thus

producing that peculiar permeation, so free from the moral element

— (or shall we say, in order not to give offence, so free

from moral cant) — which comes to expression in the

Renaissance in the South.

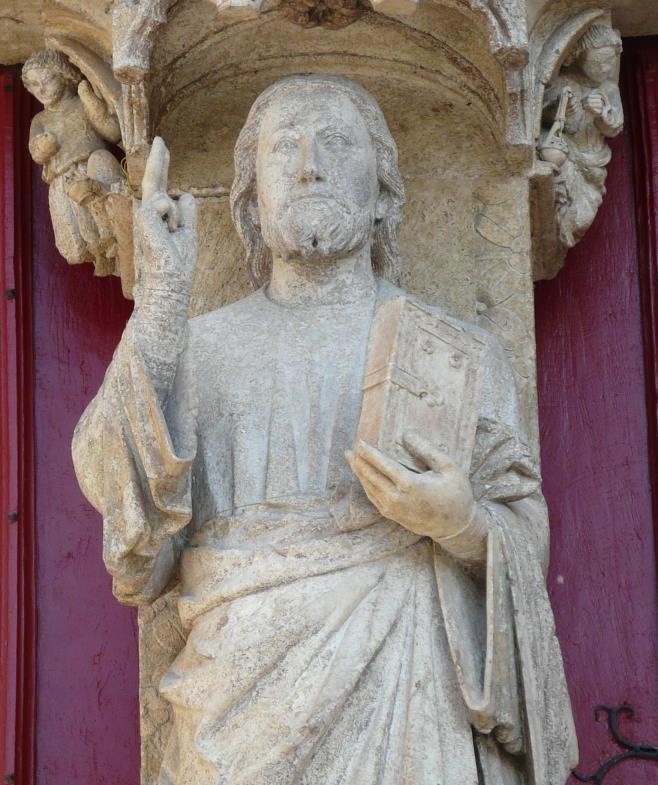

If you were to make a

study of the progress in the representation of the Christ-Figure,

this Head of Christ would be an important station. Also the Head of

Christ in the Cathedral of Amiens, and afterwards, the Head of

Christ by Albrecht Dürer.

4a. (Cathedral of Freiburg in Saxony.)

(Cathedral of Amiens)

Head of Christ by Albrecht Dürer.

We now pass to some

sculptures which are found at Freiburg in Saxony, also dating from

the first third of the 13th century. They show an altogether

different aspect, though here, too, it is the sacred history, and a

deep striving for inwardness. It is not too much to say that one

loves to dwell on every single face. The next picture:

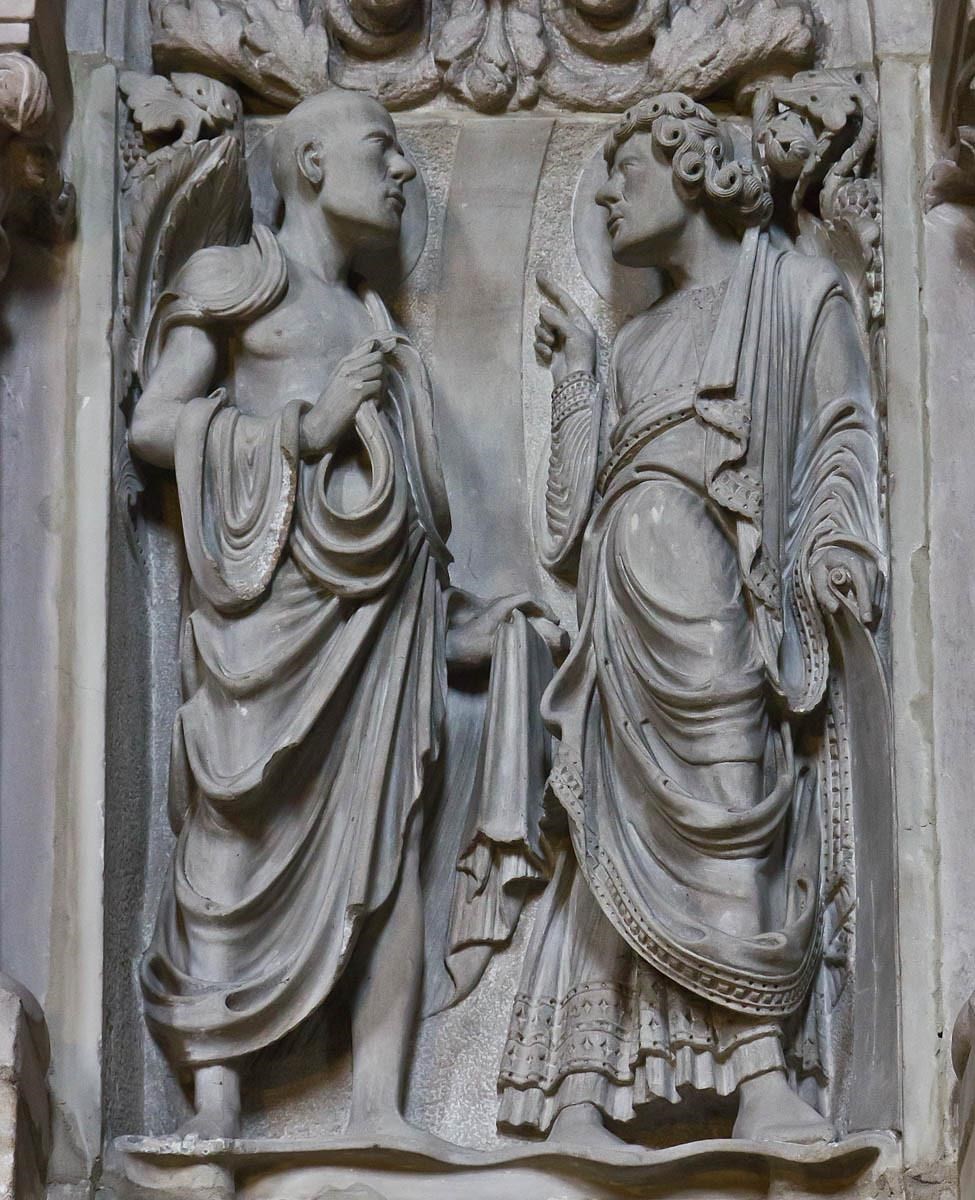

4b. From the Golden Gate, (Cathedral of Freiburg.

Saxony.)

shows us two figures.

The one, the figure of a woman, is hard to interpret. Perhaps she

is an “Ecclesia.” The other is said to be Aaron. These

things are not essential. The figures are undoubtedly connected,

allegorically or in some other way, with the Christian

world-conception. Once more, observe the deepening of the soul's

life. The contrast of expression between the face on the left, and

that on the right is particularly fascinating from this point of

view.

Two figures. (Cathedral of Freiburg. Saxony.)

Supplementing what we

showed last time of the Cathedrals at Naumburg and Strasburg, we

will now show some sculptures from the Cathedral at Bamberg. Here,

to begin with, we have two.

5. Figures of Prophets. (Cathedral at Bamberg.)

See how directly the

dramatic element, the living movement of soul, is expressed in the

attitudes, representing the interchange between one soul and

another. C. single moment is presented to us, while at the same

time the two contrasting characters are well expressed.

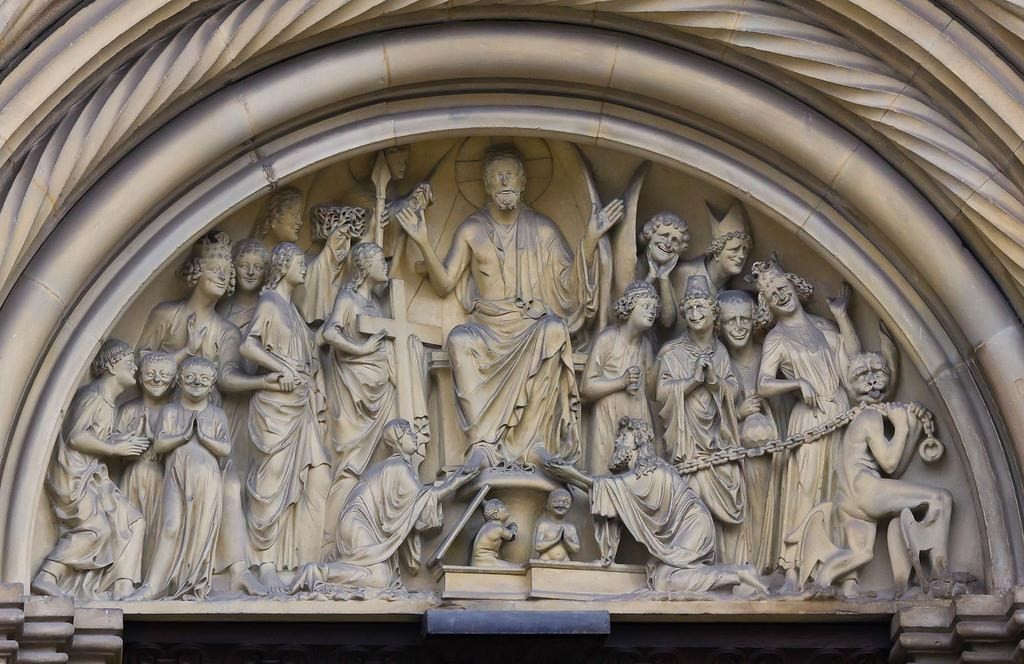

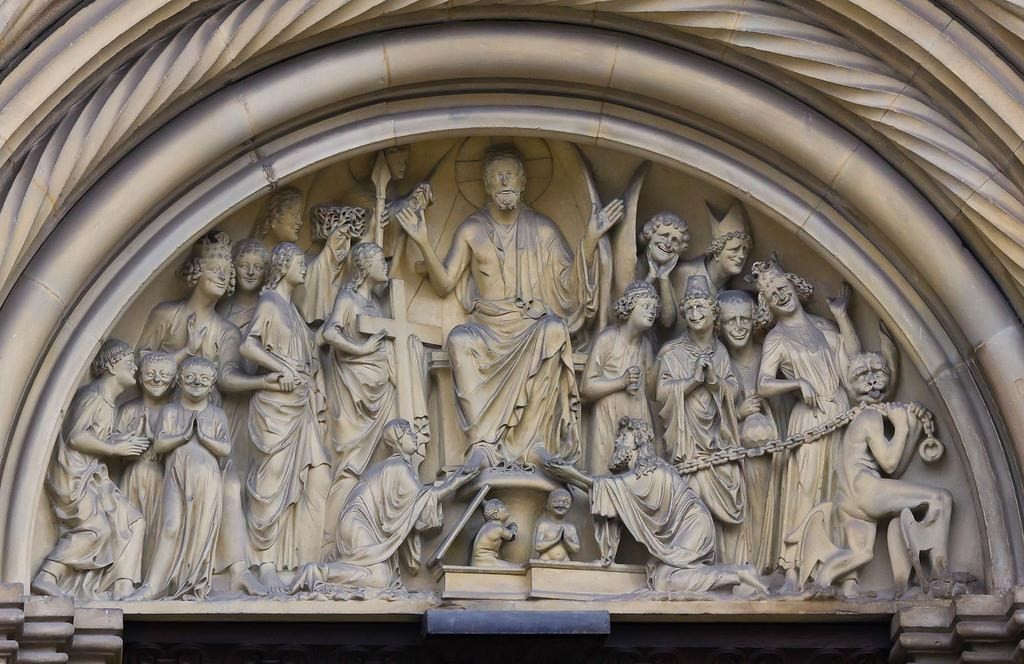

6. The Last Judgment. (Cathedral at Bamberg.)

The composition is by

no means great, but the expressiveness of soul is marvellous. He

must remember that this dates from about 1240. Spiritual scientific

research will in course of time be confirmed, in that it does not

suggest — as many people still do today — that the

Mid-European element, in its presentation of the Christian

world-conception, was in any high degree influenced by the

Southern. That, indeed, is not the case. On the contrary, the very

opposite is true.

The different streams

are not as yet clearly seen by external history. It is not seen,

for instance, what I pointed out the other day — how the

Northern impulses worked down even into the creations of Raphael

and Michelangelo. Artistically, this conception is altogether a

product of the Northern spirit.

7. The Emperor Heinrich, the Empress Kunigunde,

and St. Stephen. (Cathedral at Bamberg.)

This example shows

how the worldly and the religious elements played into one another.

This was, indeed, the case, especially at the time with which we

are now dealing. The worldly and the religious were brought

together in the effort which I characterised just now. The souls of

men had to be won over; the individual souls must first be called

— must by some means be gathered together, if they are to

look up in community, in congregation, to the spiritual world.

Likewise, they must first be called if they are to express reverence

in one way or another, for something in the outer worldly sphere.

Hence the worldly is

brought together with the ecclesiastical element. Here, then, we

see the Emperor Heinrich, the Empress Kunigunde, and, on the left,

St. Stephen.

Needless to say,

these things presuppose, as a rule, the naivete of the common

people, their blind devotion and dependence. Today, in the fond

belief of our contemporaries, these things are overcome. Inwardly,

they are present all the more. On the part of the great lords

themselves there is very frequently the underlying idea (not

unconnected with very human qualities, which shall be nameless),

that they themselves stand just a little nearer to the various

Saints and supersensible powers than ordinary mortals do.

We will now show a detail, the middle figure of this picture.

8 . The Empress Kunigunde. (Detail of above.)

9. St. Peter, Adam and Eve. (Cathedral at Bamberg.)

The Old and the New

Testament were always conceived in unison, as the promise and the

fulfilment. Follow the detail of these figures.

10. Adam. (Detail of above.)

11. Eve. (Detail of above.)

And now another

figure from the same Cathedral.

12. Mary. (Cathedral at Bamberg.)

A figure of Mary,

showing — from whatever point of view you may consider it

— how richly the qualities which I described before, come to

expression in this stream of Art. You must remember that this was

done about the year 1245. What would you look for in the South at

that time? The next Picture, from the Cathedral at Bamberg again,

represents the figure of:

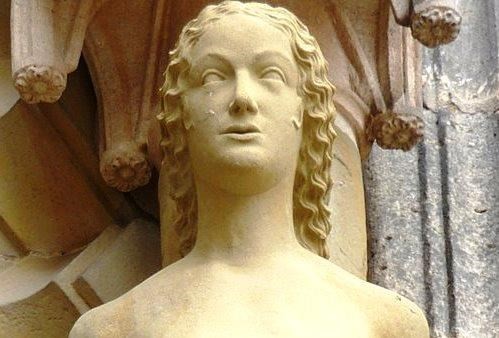

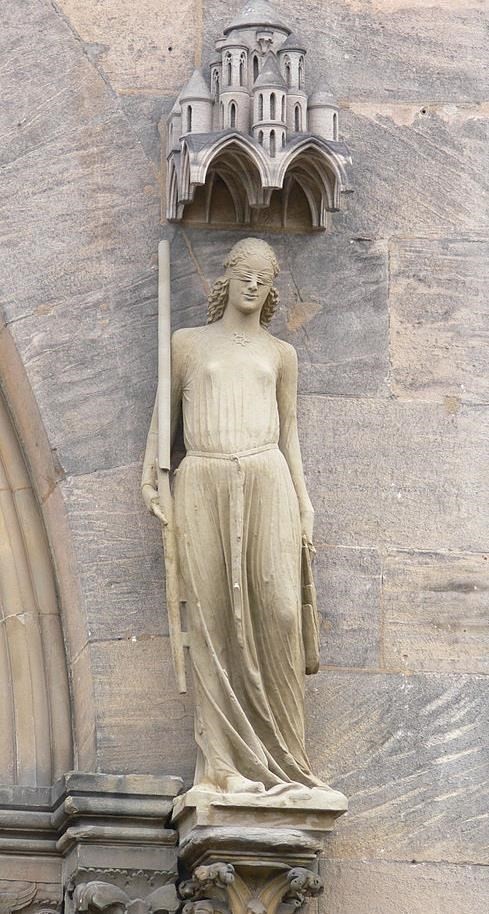

13. The Church. (Cathedral at Bamberg.)

A favorite

representation at that time. Last time we saw the corresponding

figure from the Cathedral at Strasburg. The figure of the Church is

conceived with a certain inner freedom. Her soul is free, she gazes

freely far into the world, with wisdom.

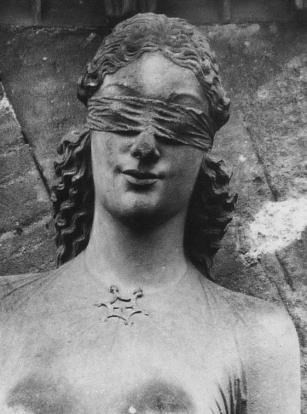

14. Head of “the Church.” (Detail of

the above.)

This figure is in

contrast, as we saw last time, with the Synagogue, who is

represented once more with bound and downcast eyes. The whole

posture is intended to represent this contrast in every detail,

even to the sweep of the drapery.

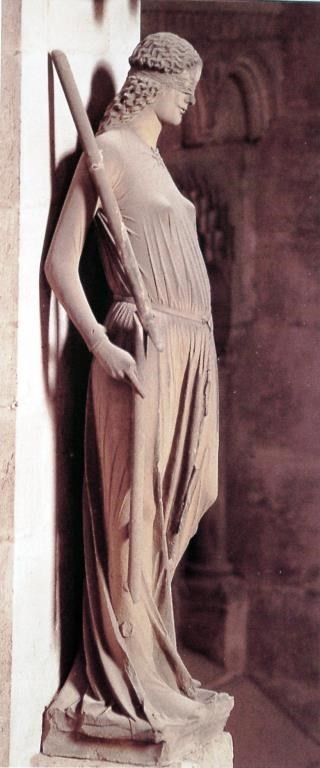

15. The Synagogue. (Cathedral at Bamberg.)

Look at the lower

portion of the dress, how well it is adapted to the movement of the

soul. We will insert the 'Church' once more, in order that you may

compare the draperies:

16. Head of the “Synagogue.” (Detail

of the above.)

And now a worldly, or

secular figure from the same Cathedral.

18. King Stephen. (Cathedral at Bamberg.)

Study the expression

well. The head, which we will now show in detail, is most

wonderful:

19. Head of King Stephen. (Detail of above.)

We now pass on to the

14th century, and see what had occurred by that time. We have a few

figures from the Cathedral at Cologne, first half of the 14th

century.

20. Mary. (Cathedral at Cologne.)

It is easy to see

that a certain decline had taken place. The next picture is also

from Cologne:

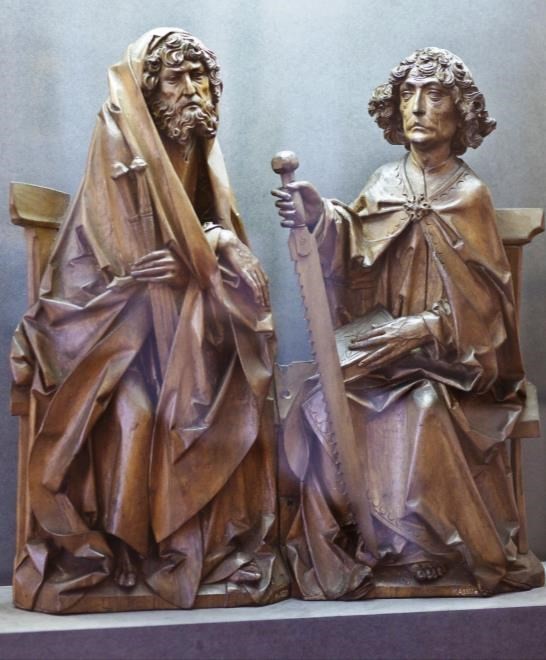

22. St. James and St. John. (Cologne Cathedral.)

Going further in the

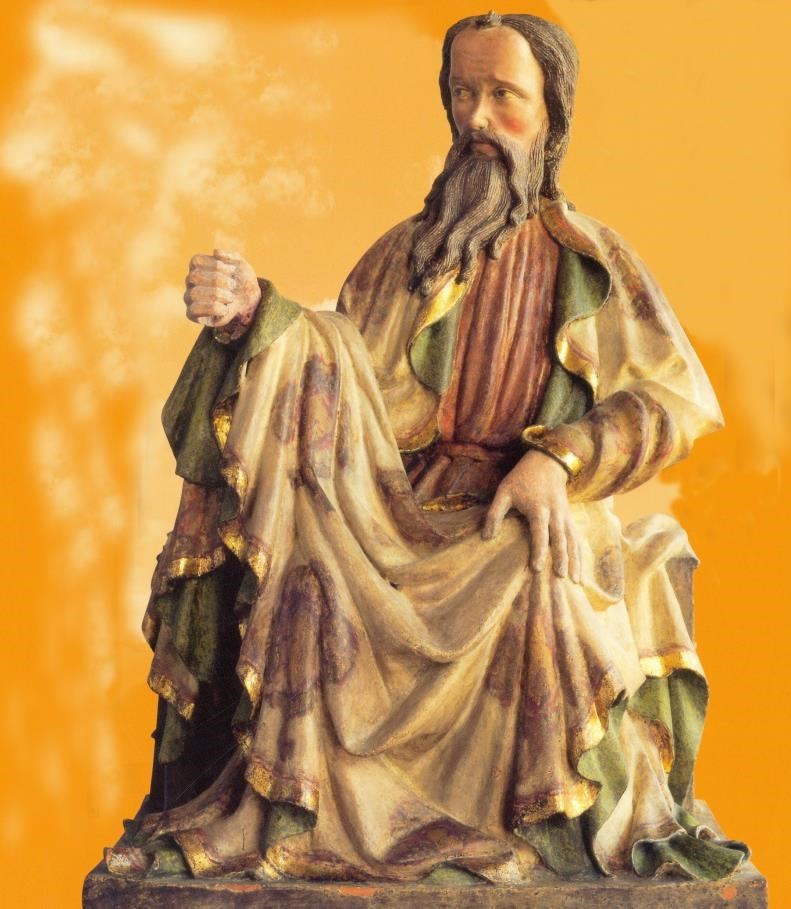

14th century we now come to a figure of St. Paul by a master known

as the “Master of the Clay Figures.” These figures were

executed in burnt earthenware.

23. The Apostle Paul. Nuremberg.

Having now shown the

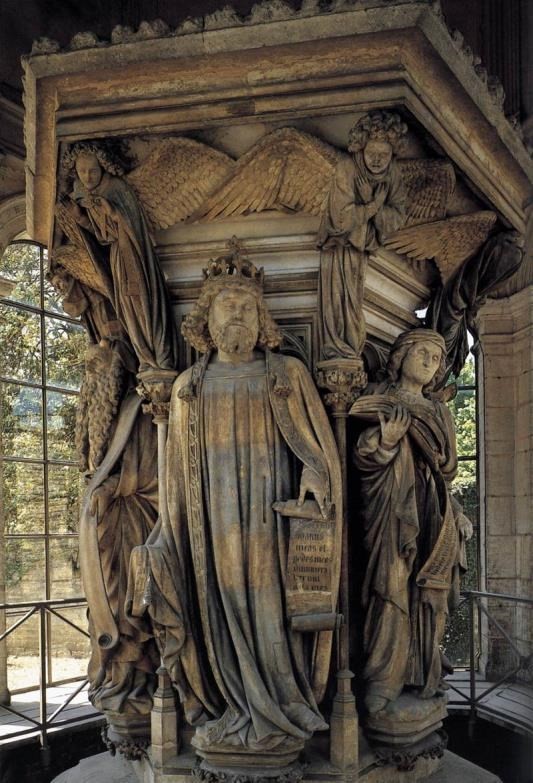

rise, and to some extent the decline of a stream of evolution

complete in itself, we will give a series of pictures from the

Chartreuse de Champmol at Dijon, which are really great of their

kind. Most, if not all of them are the independent work of the

Dutch sculptor, Sluter, or else done under his direction. He

brought to the Chartreuse at Dijon, from the Netherlands, an almost

unique power of individual characterisation. From many points of

view we see this individualising tendency in his work.

24. St. John the Baptist. Philip the Bold. The

Madonna.

25. The Madonna. (Dijon also.)

St. John the Baptist. Philip the Bold.

Here especially you

see the Art of individual characterisation. Compare this Madonna

and Child of Sluter's with the next picture (Moses) and realise the

power of one and the same man to characterise these two.

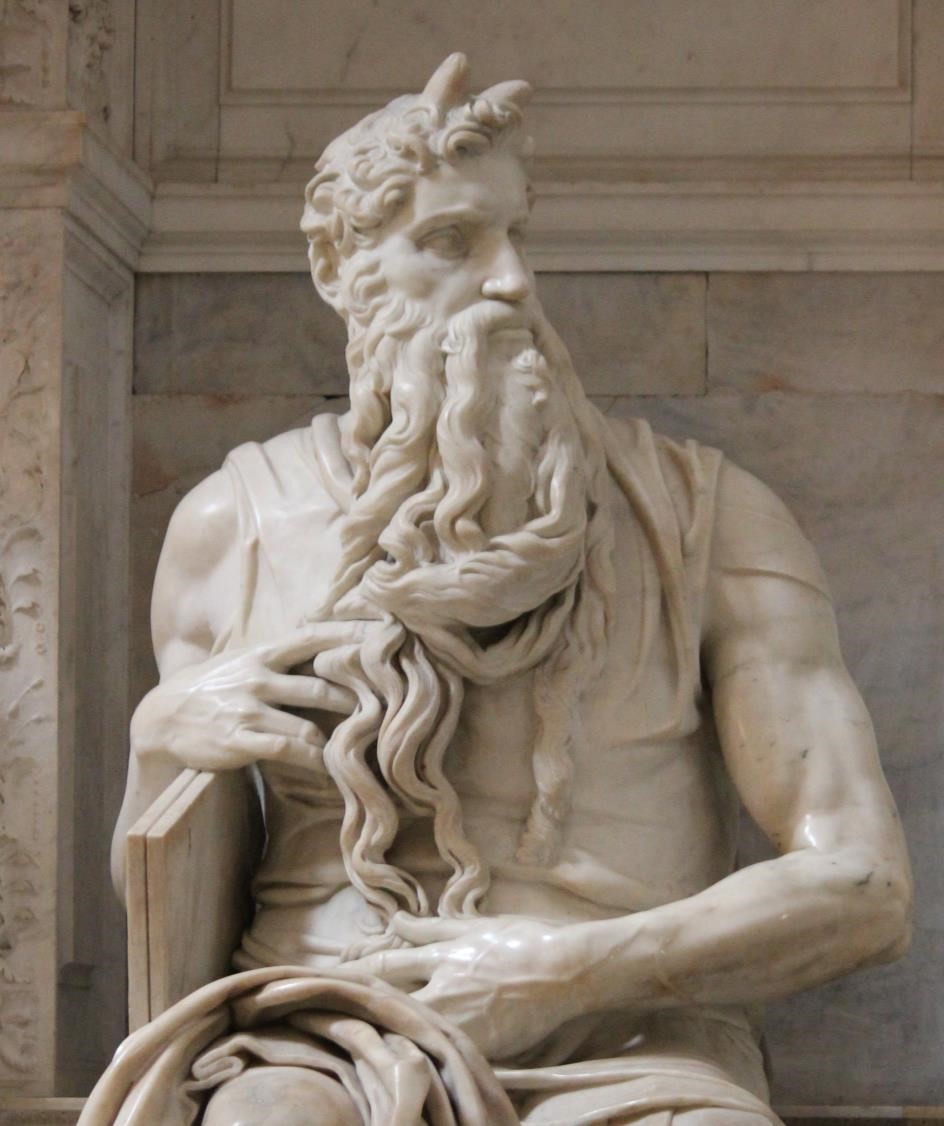

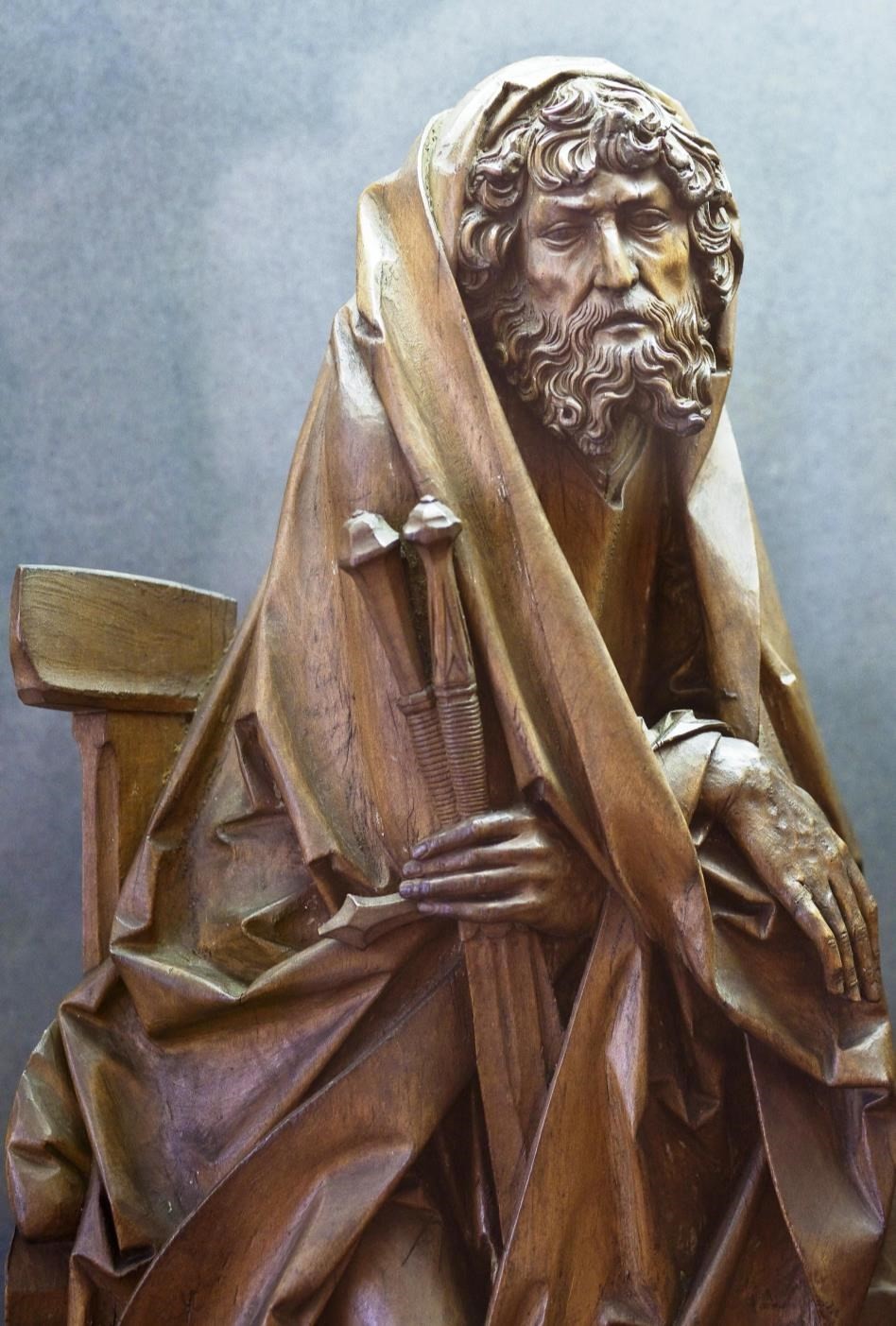

26. Moses. (Dijon.)

Remember that this

Chartreuse at Dijon was built in 1306 to 1334; it was therefore the

beginning of the 14th century. Compare this with Michelangelo's

Moses — for why should these things not be placed together

— they are, indeed, comparable.

26.b. Moses. Michelangelo. Rome.

And now by the same

artist as before — Sluter.

27. Jeremiah. David. Zachariah. (Dijon.)

28. Zachariah. Daniel. Isaiah. (Dijon.)

To live with the

prophetic figures so as to achieve this degree of

individualisation, was, indeed, most wonderful. We will now show

one of the figures in detail:

29. Jeremiah. (Detail of above.)

30. Tomb of Philip the Bold. (Dijon.)

These are by the same

artist. The age was especially great in the creation of tomb

monuments. We will show the detail of the upper part:

31. Upper portion of tomb, with two Angels.

(Detail.)

The figures round the

base of the tomb which were formerly so small, are wonderfully

executed when you come to see them in detail.

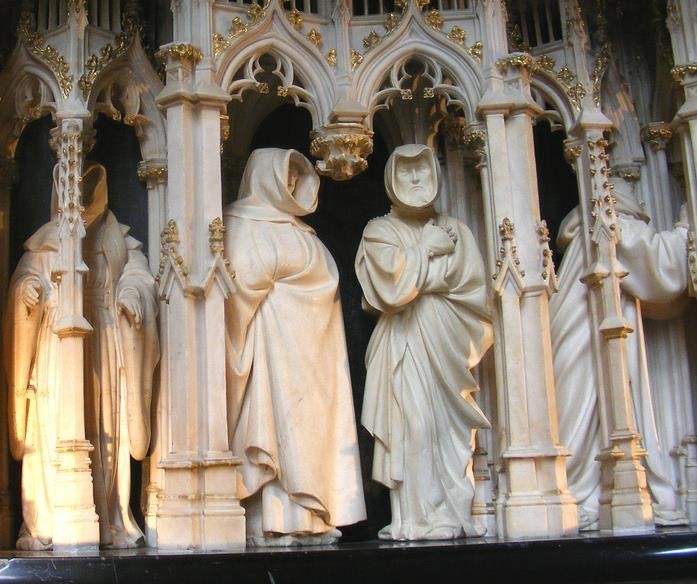

32. Figures of two monks. (Detail of above.)

Such is the

individual characterisation of all the single figures round the

base of the tomb. Here is another group.

33. Group of Monks. (Tomb of Philip the Bold. Dijon.)

We now go on to an

artist of the 15th century. (We must go according to the pictures

we possess at the moment.) The last pictures, you remember, were by

an artist of the early 14th century. With the Cologne Master, and

the Master of the Clay Figures who made the group we saw before, we

came to the 14th century. We now pass on into the 15th. Here, then,

we have two figures by

34. Multscher. St. George and Florian.

(Spitalkirche. Sterzing.)

This is about the

middle of the 15th century. The next is a Madonna, by the same

artist (Multscher).

35. Madonna. (Pfarrerkirche. Starzing.)

And now we go further

and further in what I described just now as the elaboration of the

Christian subjects with deep inwardness of soul. The following are

figures carved in wood, at Blutenburg (end of the 15th century).

The art of characterisation has, indeed, attained its ideal to a

marvellous extent.

The figure of Mary,

carved in wood — end of the 13th century:

36. St. Matthew. St. Mary. and St. John

(Klosterkirche. Blutenburg.)

This, then, is the

time when Michelangelo and Raphael were born. The next picture,

too, is from Blutenburg.

37. St. Matthew. St. Mary. and St. John

(Klosterkirche. Blutenburg.)

The time when these

highly individual figures were created was also especially great in

wood-carving, with which they decorated the Choristers' seats in

their churches. We will give two examples from the Frauenkirche in

Munich, end of the 15th century.

40. Frauenkirche. Munich (The Choir, detail.)

41. Frauenkirche. Munich. (The Choir, detail.)

We now come to the

sculptor who worked at the end of the 15th century.

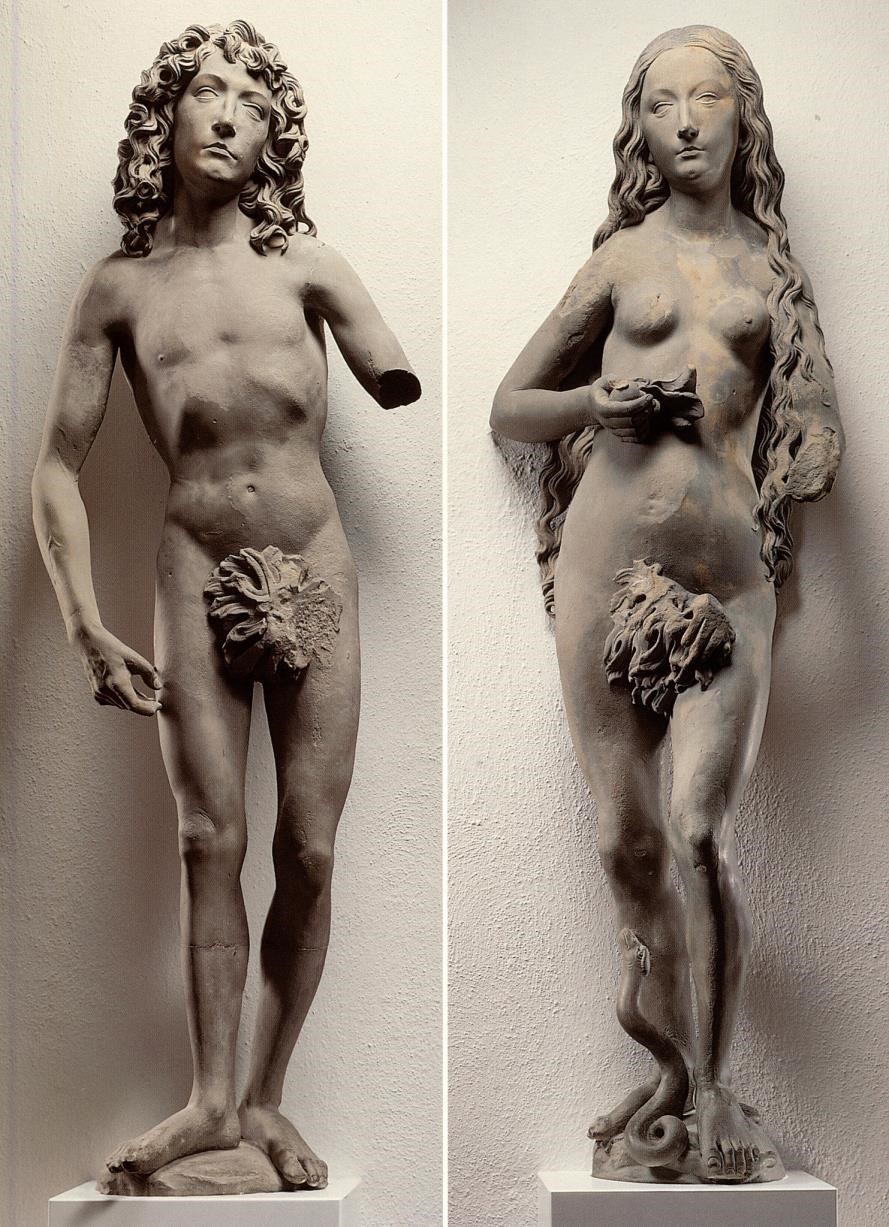

42. Tilman Riemenschneider. Adam. (Wurzburg.)

43. Head of Adam. (Detail of above. Wurzburg.)

And this was the time

when the High Renaissance in Italy had not as yet begun. These

works were created about 1490–1495.

44. Eve. Til Riemenschneider. (Wurzburg.)

45. Head of Eve. Til Riemenschneider. (Detail of

above.)

46. Til Riemenschneider. St. Elizabeth.

(Nuremberg.)

This St. Elizabeth

— created in the early 16th century — is now in the

(Germanisches Museum, at Nuremberg.)

47. Til Riemenschneider. Madonna and Child.

(Frankfort.)

This, too, dates from

the beginning of the 16th century.

48. Til Riemenschneider. The Twelve Apostles.

(Frankfort.)

There are wonderful

types among these twelve Apostles; one would like to study every

single head alone:

Peter

James the Younger

Thaddeus

Andrew

Philip

Bartholomew

John

James the Elder

Matthias

Simon

Matthew

Thomas

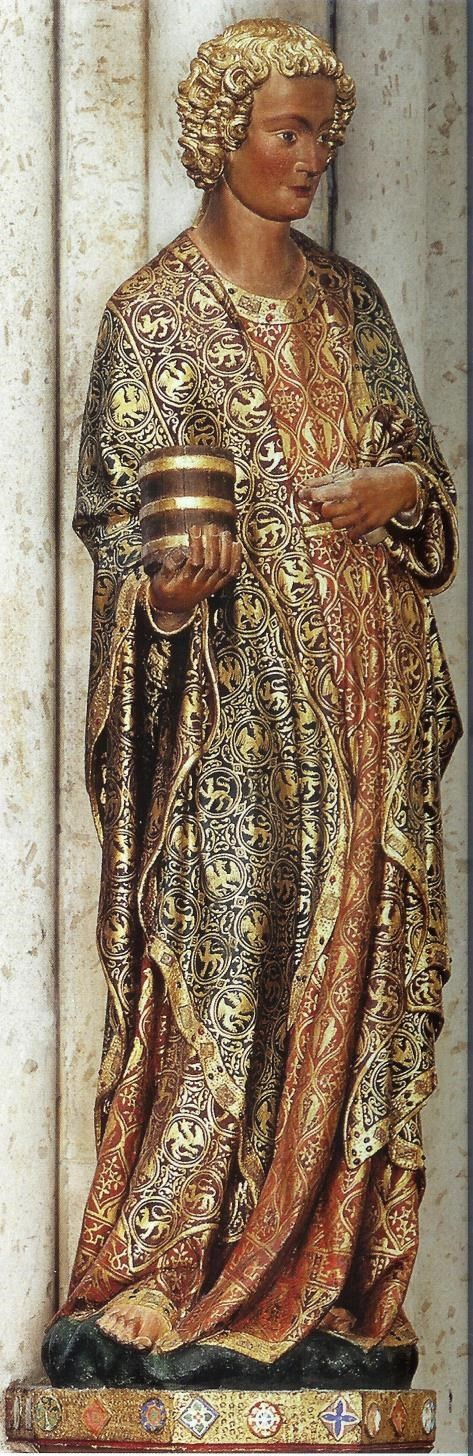

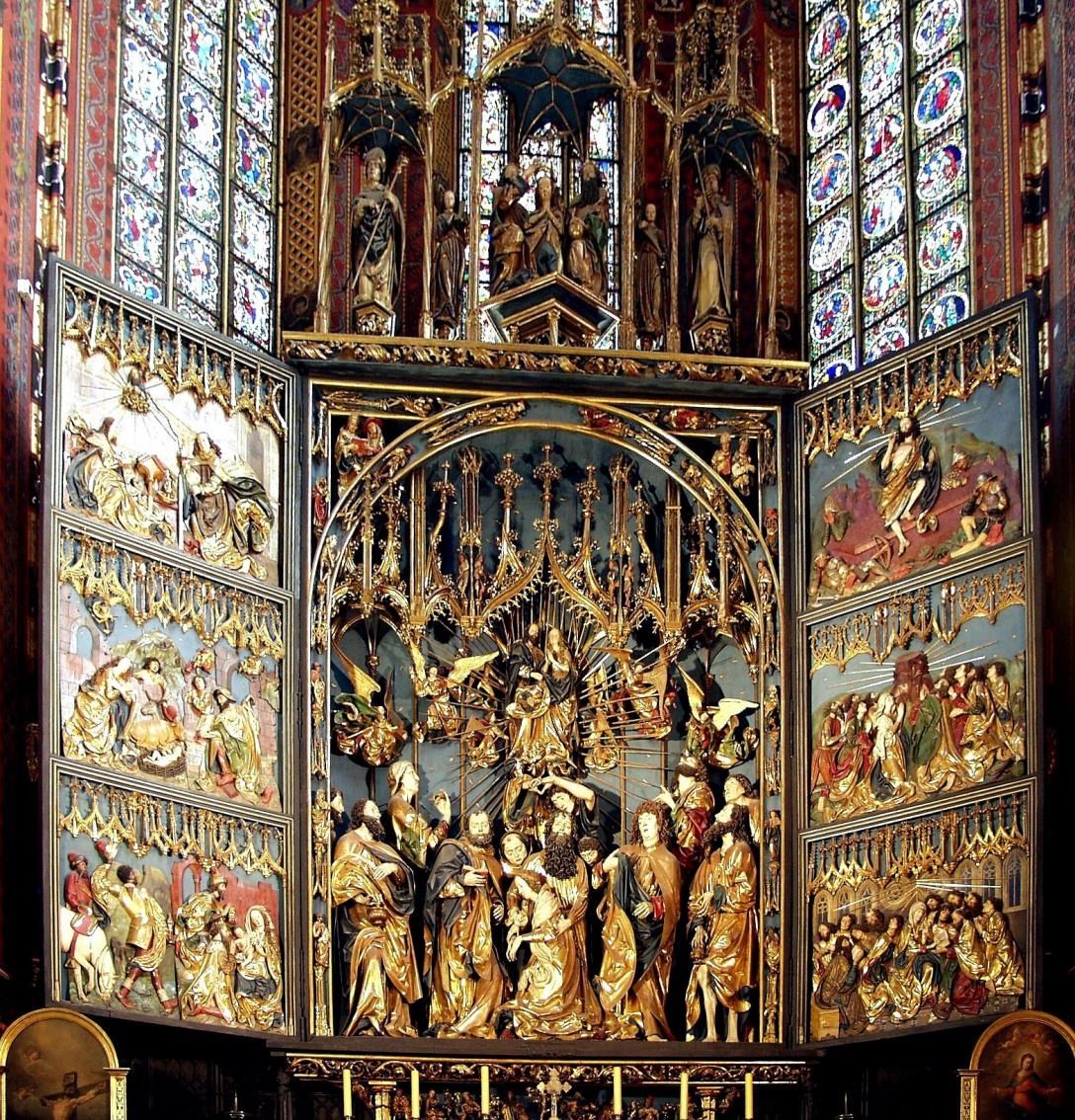

Finally, we give two

examples of the sculptor — Veit Stoss — early 16th

century, who worked in Cracow and also in Southern Germany,

creating his plastic works in many different materials.

49. Veit Stoss. Marienaltar. (Cracow.)

The next picture is

in Nuremberg,. “The Angel's Greeting,” it is

called.

50. Veit Stoss. ‘Ingelischen Gruss.’

(Nuremberg.)

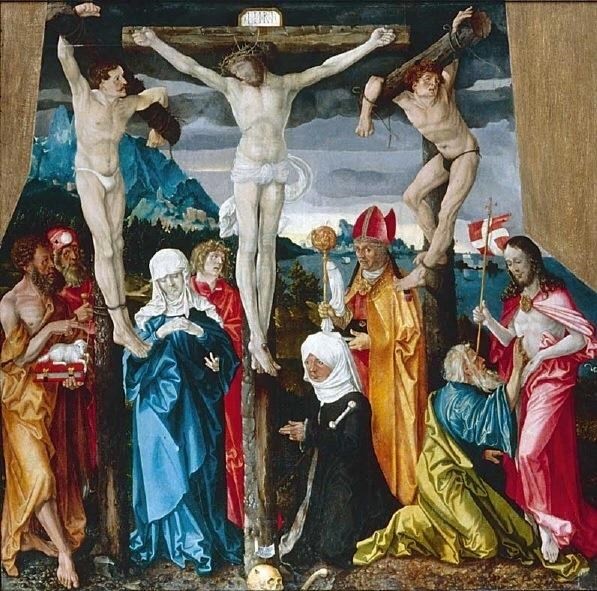

I will also show

three paintings by Hans Baldung, also known as Hans Grun,

who worked in Dürer's workshop at the beginning of the 16th

century — about 1507–1509.

51. Hans Baldung. The Flight into Egypt.

(Germanisches Museum. Nuremberg.)

His pictures reveal

once more, in the sphere of painting, how everything is turned

towards the life of the soul.

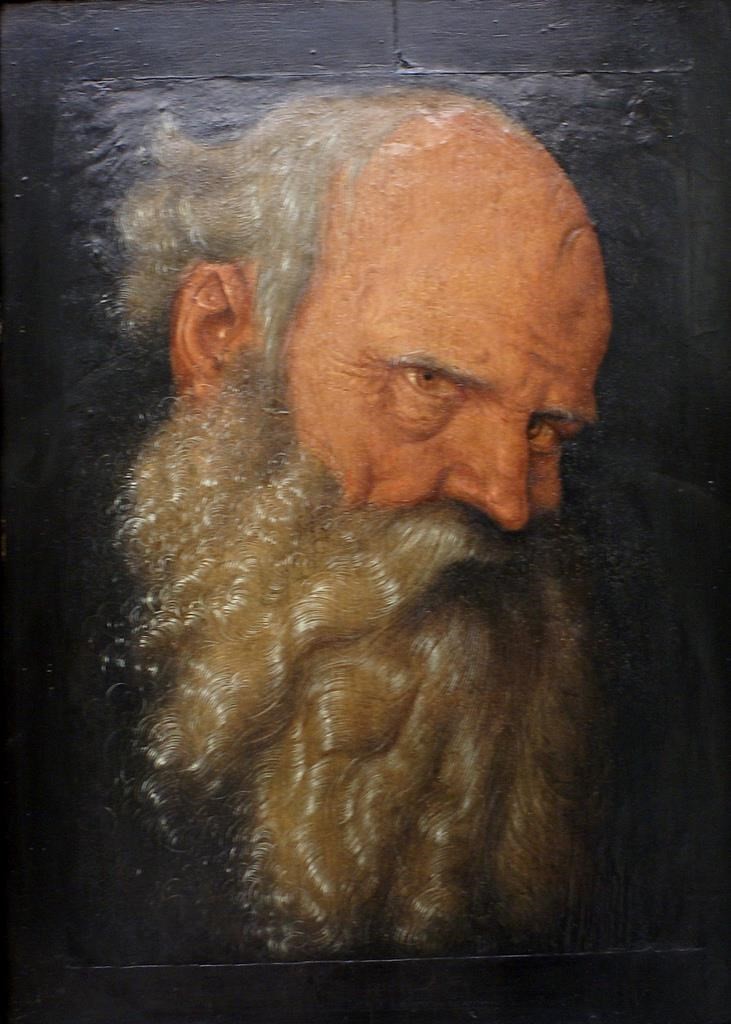

52. Hans Baldung. Crucifixion. (Berlin Gallery.)

Hans Baldung was also

a portrait painter of no mean order. Here you have an example.

53. Hans Baldung. Head of an Old Man. (Berlin

Museum.)

Here you see how the

same master cultivated the art of portraiture. He was a pupil of

Dürer's, who subsequently lived at Strasburg, and at Freiburg

in Breisgau. He did some wonderful paintings of the Life of Christ,

and of the Mother of Christ. You will find a picture by him at

Basel — “Christ on the Cross.”

This picture, then, is of the early 16th century

— the time of Raphael and Michelangelo in Rome.

My dear Friends, the

more we multiply these pictures, the more should we see, from this

juxtaposition of the Northern and Southern Art, what an immense

revolution took place at the turn of the fourth and fifth

Post-Atlantean Epochs. And the more should we realise how

infinitely rich in content is the simple statement that at that

historic moment Civilisation passed from the development of the

Intellectual, or Feeling Soul into that of the Spiritual Soul.

Infinitely much is contained in such a simple statement. But we

only learn to understand these things of Spiritual Science rightly

when we follow them into the several and detailed domains of human

life.

In conclusion, my

dear Friends, I still wish to speak a word of solemn remembrance to

you on this day. The day after tomorrow is the anniversary of the

death of our dear friend, Fraulein Stinde, and in our hearts we

will not forget to think on that day of all that came into our

Movement through the work of this dear and valued member.

And we will also turn

our thoughts to her soul as she works on in the Spiritual Worlds

— deeply and lovingly connected as she is with our Movement.

On this day especially we will deepen the thoughts and feelings of

our hearts which are directed to her.

I only wished to add

this word of remembrance to remind you of the day after tomorrow.

In memory of all that

unites us with our dear friend — with the soul of our dear

Sophie Stinde — let us now rise from our seats.

|