III

Distribution of Man's Inner Impulses in the

Course of His Life,

-or-

Brotherliness and Freedom ...

Dornach

25th December, 1918

When I made some suggestions

last Sunday for a renewal of our Christmas thinking, I spoke of the

real, inner human being who comes from the spiritual world and unites

with the body that is given to him from the stream of heredity. I described

how this human being, when he enters the life he is to experience between

birth and death, enters it with a certain sense of equality. I said

that someone who observes a child with understanding will notice how

he does not yet know of the distinctions that exist in the human social

structure, due to all the relationships into which men's karma

leads them. I said that if we observe clearly and without prejudice

the forces residing in certain capacities and talents, even in genius,

we shall be compelled to ascribe these in large measure to the impulses

which affect mankind through the hereditary stream; that when such impulses

appear clearly in the natural course of that stream, we must call them

luciferic. Moreover, in our present epoch these impulses will only be

fitted into the social structure properly if we recognize them as luciferic,

if we are educated to strip off the luciferic element and, in a certain

sense, to offer upon the altar of Christ what nature has bestowed upon

us — in order to transform it.

There are two opposite points

of view: one is concerned with the differences occurring in mankind

through heredity and conditions of birth; the other with the fact that

the real kernel of a man's being holds within it at the beginning

of his earthly life the essential impulse for equality. This shows that

the human being is only observed correctly when he is observed through

the course of his whole life, when his development in time is really

taken into account. We have pointed out in another connection that the

developmental motif changes in the course of life. You will also find

reference to this in an article I wrote called “The Ahrimanic

and the Luciferic in Human Life,” where it is shown that the luciferic

influence plays a certain role in the first half of life, the ahrirnanic

in the second half; that both these impulses are active throughout life,

but in different ways.

Along with the idea of equality,

other ideas have recently been forced into prominence in a tumultuous

fashion, in a certain sense precipitating what should have been a tranquil

development in the future. They have been set beside the idea of equality,

but they should really be worked out slowly in human evolution if they

are to contribute to the well-being of humanity and not to disaster.

They can only be rightly understood and their significance for life

rightly estimated if they are given their proper place in the sequence

of a man's life.

Side by side with the idea

of equality, the idea of freedom resounds through the modern world.

I spoke to you about the idea of freedom some time ago in connection

with the new edition of my

The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity.

We are therefore able to appreciate the full importance and range of

this impulse in relation to the innermost kernel of man's being. Perhaps

some of you know that it has frequently been necessary, from questions

here and there, to point to the entirely unique character of the conception

of freedom as it i is delineated in my

The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity.

There is a certain fact that I have always found necessary to emphasize

in this connection, namely, that the various modern philosophical conceptions

of freedom have made the mistake (if you want to call it a mistake)

of putting the question thus: Is the human being free or not free? Can

we ascribe free will to man? or may we only say that he stands within a

kind of absolute natural necessity, and out of this necessity accomplishes

his deeds and the resolves of his will? This way of putting the question is

incorrect. There is no “either-or.” One cannot say, man is

either free or unfree. One has to say, man is in the process of development

from unfreedom to freedom. And the way the impulse for freedom is conceived

in my

The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity,

shows you that man

is becoming ever freer, that he is extricating himself from necessity,

that more and more impulses are growing in him that make it possible

for him to be a free being within the rest of the world order.

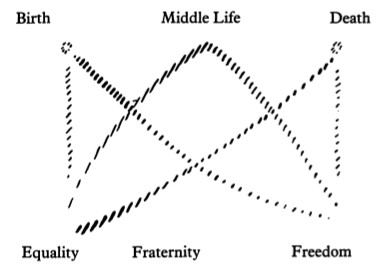

Thus the impulse for equality

has its greater intensity at birth — even though not in consciousness,

since the latter is not yet developed — and it then decreases.

That is to say, the impulse for equality has a descending development.

We may make a diagram thus:

At birth we find the height

of the impulse for equality, and it moves in a descending curve. With

the impulse for freedom the reverse is true. Freedom moves in an ascending

curve and has its culmination at death. By that I do

not mean to say that man reaches the summit of a freely-acting being

when he passes through the gate of death; but relatively, with regard

to human life, a man develops the impulse for freedom increasingly up

to the moment of death, and he has achieved relatively the greatest

possibility of becoming free at the moment he enters the spiritual world

through the gate of death. That is to say: while at birth he brings

with him out of the spiritual world the sense of equality which then

declines during the course of physical life, it is just during his physical

lifetime that he develops the impulse toward freedom, and he then enters

the spiritual world through the gate of death with the largest measure

of this impulse for freedom that he could attain in the course of his

physical life.

You see again how one-sidedly

the human being is often observed. One fails to take into account the

time element in his being. He is spoken of in general terms, in

abstracto, because people are not inclined today to consider realities.

But man is not a static being; he is an evolving being. The more he

develops and the more he makes it possible to develop, so much the more

does he fulfill his true task here in the course of physical life. People

who are inflexible, who are disinclined to undergo development, accomplish

little of their real earthly mission. What you were yesterday you no

longer are today, and what you are today you will no longer be tomorrow.

These are indeed slight shades of differences; but happy is he in whom

they exist at all—for standing still is ahrimanic! There should

be shades of difference. No day should pass in a man's life without

his receiving at least one thought that alters his nature a little,

that enables him to develop instead of merely to exist. Thus we recognize

man's true nature — not when we insist in an absolute sense that

mankind has the right to freedom and equality in this world —

but only when we know that the impulse for equality reaches its culmination

at the beginning of life, and the impulse toward freedom at the end.

We unravel the complexity of human development in the course of life

here on earth only when we take such things into consideration. One

cannot simply look abstractly at the whole man and say: he has the right

to find freedom, equality, and so forth, within the social structure.

These things must be brought to people's attention again through spiritual

science, for they have been ignored by the recent developments that

move toward abstract ideas and materialism.

The third impulse, fraternity,

has its culmination, in a certain sense, in the middle of life. Its

curve rises and then falls. (See diagram.) In the middle of life, when

the human being is in his least rigid condition — that is, when

he is vacillating in the relation of soul to body — then it is

that he has the strongest tendency to develop brotherliness. He does

not always do so, but at this time he has the predisposition to do so.

The strongest prerequisites for the development of fraternity exist

in middle life.

Thus these three impulses

are distributed over an entire lifetime. In the times we are approaching

it will be necessary for our understanding of other men, and also —

as a matter of course — for our so-called self-knowledge, that

we take such matters into account. We cannot arrive at correct ideas

about community life unless we know how these impulses are distributed

in the course of life. In a certain sense we Will be unable to live

our lives usefully unless we are willing to gain this knowledge; for

we will not know exactly what relation a young man bears to an old man,

or an older person

to one in middle life, unless we keep in mind the special configuration

of these inner impulses.

But now let us connect all

this with lectures

[

Note 5 ]

I gave here earlier about the whole human race gradually becoming younger.

Perhaps you recall that I explained how the particular dependence of

soul development upon the physical organism that a human being has today

only during his very earliest years was experienced in ancient times

up to old age. (We are speaking now only of post-Atlantean epochs.)

I said that in the ancient Indian cultural epoch man was dependent upon

his so-called physical development into his fifties, in the way that

he is now dependent only in the earliest years. Now in the first years

of life man is dependent upon his physical development. We know the

kind of break the change of teeth causes, then puberty, and so on. In

these early years we see a distinct parallel in the development of soul

and of body; then this ceases, vanishes. I pointed out that in older

cultural epochs of our post-Atlantean period that was not the case.

The possibility of receiving wisdom from nature simply through being

a human being — lofty wisdom which was venerated among the ancient

Indians, and could still be venerated among the ancient Persians—that

possibility existed because the conditions were not the same as they

are now. Now a man becomes a finished product in his twenties; he is

then no longer dependent upon his physical organism. Starting from his

twenties, it gives him nothing more. This was not the case in ancient

times. In ancient times the physical organism itself gave wisdom to

man's soul into his fifties. It was possible for him in the second half

of life, even without special occult training, to extract the forces

from his physical organism in an elemental way, and thus attain a certain

wisdom and a certain development of will. I pointed to the significance

of this for the ancient Indian and Persian epochs, even for the Egypto-Chaldean

epoch, when it was possible to say to a boy or girl, or young man or

young woman: “When you are old you may expect that something will

come into your life, will be bestowed upon you simply by your having

become old, because one continues to develop up to the time of death.”

Age was looked up to with reverence , because a man said to himself:

With old age something will enter my life that I cannot know or cannot

will while I am still young. That gave a certain structure to the entire

social life which only ceased when during the Greco-Latin epoch this

point of time fell back into the middle years of human life. In the

ancient Indian civilization man was capable of development up to his

fifties. Then during the ancient Persian epoch mankind grew younger:

that is, the age of the human race, the capacity for development, fell

back to the end of a man's forties. During the Egypto-Chaldean epoch

it came between the thirty-fifth and the forty-second year. During the

Greco-Latin epoch he was only capable of development up to a point of

time between the twenty-eighth and the thirty-fifth year. When the Mystery

of Golgotha occurred, he had this capability up to the thirty-third

year. This is the wonderful fact we discover in the history of mankind's

evolution: that the age of Christ Jesus when he passed through death

on Golgotha coincides with the age to which humanity had fallen back

at that time.

We pointed out that humanity

is still becoming younger and younger; that is, the age at which it

is no longer capable of development continues to decrease. This is significant,

for example, when today a man enters public life at the particular age

at which humanity now stands — twenty-seven years — without

having received anything beside what he took in from the outside up

to his twenty-seventh year. I mentioned that in this sense Lloyd-George

[

Note 6 ]

is the representative man

of our time. He entered public life at twenty-seven years. This had

far-reaching consequences, which you can of course discover by reading

his biography. These facts enable one to understand world conditions

from within.

Now what strikes you as

the most important fact when you connect what we have just been indicating

— the increasing youthfulness of the human race — with the

thoughts we have brought before our souls in these last days in relation

to Christmas? The state of our development since the Mystery of Golgotha

is this, that starting from our thirtieth year we can really gain nothing

from our own organism, from what is bestowed upon us by nature. If the

Mystery of Golgotha had not taken place, we would be going about here

on earth after our 30th year saying to ourselves: Actually we live in

the true sense only up to our thirty-second or thirty-third year at

most. Up to that time our organism makes it possible for us to live;

then we might just as well die. For from the course of nature, from

the elemental occurrences of nature, we can gain nothing more for our

soul development through the impulses of our organism. If the Mystery

of Golgotha had not taken place, the earth would be filled with human

beings lamenting thus: Of what use to me is life after my thirty-third

year? Up to that time my organism can give me something. After that

I might just as well be dead. I really go about here on earth like a

living corpse. If the Mystery of Golgotha had not taken place, many

people would feel that they are going about on earth like living corpses.

But the Mystery of Golgotha, dear friends, has still to be made fruitful.

We should not merely receive the Impulse of Golgotha unconsciously,

as people now do: we should receive it consciously, in such a manner

that through it we may remain youthful up to old age. And it can indeed

keep us healthy and youthful if we receive it consciously in the right

way. We shall then ' be conscious of its enlivening effect upon our

life. This is important!

Thus you see that the Mystery

of Golgotha can be regarded as something intensely alive during the

course of our earthly life. I said earlier that people are most predisposed

to brotherliness in the middle of life — around the thirty-third

year, but they do not always develop it. You have the reason for this

in what I just said. Those who fail to develop brotherliness, who lack

something of brotherliness, simply are too little permeated by the Christ.

Since the human being begins to die, in a certain sense, in middle age

from the forces of nature, he cannot properly develop the impulse, the

instinct, of brotherliness—and still less the impulse toward freedom,

which is taken up so little today — unless he brings to life within

himself thoughts that come directly from the Christ Impulse. When we

turn to the Christ Impulse, it enkindles brotherliness in us directly.

To the degree to which a man feels the necessity for brotherliness,

he is permeated by Christ.

One is also unable alone

to develop the impulse for freedom to full strength during the remainder

of one's earthly life. (In future periods of evolution this will be

different.) Something entered our earth evolution as human being and

flowed forth at the death of Christ Jesus to unite Itself with the earthly

evolution of humanity. Therefore Christ is the One who also leads present-day

mankind to freedom. We become free in Christ when we are able to grasp

the fact that the Christ could really not have become older, could not

have lived longer, in a physical body than up to the age of thirty-three

years. Suppose hypothetically that He had lived longer: then He would

have lived on in a physical body into the years when according to our

present earth evolution this body is destined for death. The Christ

would have taken up the forces of death. Had he lived to be forty years

old, He would have experienced the forces of death in His body. These

He would not have wished to experience. He could only have wished to

experience those forces that are still the freshening forces for a human

being. He was active up to His thirty-third year, to the middle of life;

as the Christ He enkindled brotherliness. Then He caused the spirit

to flow into human evolution: He gave over to the Holy Spirit what was

henceforth to be within the power of man. Through this Holy Spirit,

this health-giving Spirit, a human being develops to freedom toward

the end of his life. Thus is the Christ Impulse integrated into the

concrete life of humanity.

This permeation of man's

inner being by the Christ Principle must be incorporated into human

knowledge as a new Christmas thought. Mankind must know that we bring

equality with us out of the spiritual world. It comes, one might say,

from God the Father, and is given to us to bring to earth. Then brotherliness

reaches its proper culmination only through the help of the Son. And

through the Christ united with the Spirit we can develop the impulse

for freedom as we draw near to death.

This activity of the Christ

Impulse in the concrete shaping of humanity is something that from now

on must be accepted consciously by human souls. This alone will be really

health-giving when people's demands for refashioning the social structure

become more and more urgent and passionate. In this social structure

there live children, youths, middle-aged and old people; and a social

structure that embraces them all can only be achieved when it is realized

that human beings are not simply abstract Man. The five-year-old child

is Man, the twenty-year-old youth, the twenty-year-old young woman,

the forty-year-old man — at the present time to undertake an actual

observation of human beings, which would result in a consciousness of

humanity in the concrete, human beings as they really are. When they

are looked at concretely, the abstraction Man-Man-Man has no reality

whatsoever. There can only be the fact of a specific human being of

a specific age with specific impulses. Knowledge of Man must be acquired,

but it can only be acquired by studying the development of the essential

living kernel of the human being as he progresses from birth to death.

That must come, my dear friends. And probably people will not be inclined

to receive such things into their consciousness until they are again

able to take a retrospective view of the evolution of mankind.

Yesterday I drew your attention

to something that entered human evolution with Christianity. Christianity

was born out of the Jewish soul, the Greek spirit, and the Roman body.

These were the sheaths, so to speak, of Christianity. But within Christianity

is the living Ego, and this can be separately observed when we look

back to the birth of Christianity. For the external historian this birth

of Christianity has become very chaotic. What is usually written today

about the early centuries of Christianity, whether from a Roman Catholic

or a Protestant point of view, is very confused wisdom. The essence

of much that existed in those first Christian centuries is either entirely

forgotten by present theologians or else it has become, may I say, an

abomination for them. Just read and observe the strange convulsions

of intellectualism — they almost become a kind of intellectual

epilepsy — when people have to describe what lived in the first

centuries of Christianity as the Gnosis.

[

Note 7 ]

It is considered a sort of devil, this Gnosis, something so

demonic that it should absolutely not be admitted into human life. And

when such a theologian or other official representative of this or that

denomination can accuse anthroposophy of having something in common

with gnosticism, he believes he has made the worst possible charge.

Underlying all this is the

fact that in the earliest centuries of Christianity gnosticism did indeed

penetrate the spiritual life of European humanity — so far as

this was of importance for the civilization of that time — and,

moreover, much more significantly than is now supposed. There exists

on the one hand, not the slightest idea of what this Gnosis actually

was; on the other hand, I might say, there is a mysterious fear of it.

To most of the present-day official representatives of any religious

denomination the Gnosis is something horrible. But it can of course

be looked at without sympathy or antipathy, purely objectively. Then

it would best be studied from a spiritual scientific standpoint, for

external history has little to offer. Western ecclesiastical development

took care that all external remains of the Gnosis were properly eradicated,

root and branch. There is very little left, as you know — only

the Pistis Sophia and the like — and that gives only

a vague idea of it. Otherwise the only passages from the Gnosis that

are known are those refuted by the Church Fathers. That means really

that the Gnosis is only known from the writings of opponents, while

anything that might have given some idea of it from an external, historical

point of view has been thoroughly rooted out.

An intellectual study of

the development of Western theology would make people more critical

on this point as well—but such study is rare. It would show them,

for instance, that Christian dogma must surely have its foundation in

something quite different from caprice or the like. Actually, it is

all rooted in the Gnosis. But its living force has been stripped away

and abstract thoughts, concepts, the mere hulls are left, so that one

no longer recognizes in the doctrines their living origin. Nevertheless,

it is really the Gnosis. If you study the Gnosis as far as it can be

studied with spiritual scientific methods, you will find a certain light

is thrown upon the few things that have been left to history by the

opponents of gnosticism. And you will probably realize that this Gnosis

points to the very widespread and concrete atavistic-clairvoyant world

conception of ancient times. There were considerable remnants of this

in the first post-Atlantean epoch, less in the second. In the third

epoch the final remnants were worked upon and appeared as gnosticism

in a remarkable system of concepts, concepts that are extraordinarily

figurative. Anyone who studies gnosticism from this standpoint, who

is able to go back, even just historically, to the meager remnants —

they are brought to light more abundantly in the pagan Gnosis than in

Christian literature — will find that, as a matter of fact, this

Gnosis contained wonderful treasures of wisdom relating to a world with

which people of our present age refuse to have any connection. So it

is not at all surprising that even well-intentioned people can make

little of the ancient Gnosis.

Well-intentioned people?

I mean, for instance, people like Professor Jeremias of Leipzig, who

would indeed be willing to study these things. But he can form no mental

picture of what these ancient concepts refer to — when, for example,

mention is made of a spiritual being Jaldabaoth, who is supposed with

a sort of arrogance to have declared himself ruler of the world, then

to have been reprimanded by his mother, and so on. Even from what has

been historically preserved, such mighty images radiate to us as the

following: Jaldabaoth said, “I am God the Father; there is no

one above me.” And his mother answered, “Do not lie! Above

thee is the Father of all, the first Man, and the Son of Man.”

Then — it is further related — Jaldabaoth called his six

co-workers and they said, “Let us make man in our image.”

Such imaginations, quite self-explanatory, were numerous and extensive

in what existed as the Gnosis. In the Old Testament we find only remnants

of this pictorial wisdom preserved by Jewish tradition. It lived especially

in the Orient, whence its rays reached the West; and only in the third

or fourth century did these begin to fade in the West. But then there

were still some after-effects among the Waldenses and Cathars

[

Note 8 ]

that finally died out.

People of our time can hardly

imagine the condition of the souls living in civilized Europe during

the first Christian centuries, in whom there lived not merely mental

pictures like those of present-day Roman Catholics, but in a supreme

degree vivid, unmistakable echoes of this mighty world-picture of the

Gnosis. What we see when we look back at those souls is vastly different

from what we find in books that have been written about these centuries

by ecclesiastical and secular theologians and other scholars. In the

books there is nothing of all that lived in those great and powerful

imaginative pictures describing a world of which, as I have said, people

of our time have no conception. That is why a man possessing present-day

scholarship can do nothing with such concepts — for instance,

with Jaldabaoth, his mother, the six co-workers, and so on. He does

not know what to do with them. They are words, word-husks; what they

refer to, he does not know. Still less does he know how the people of

that earlier age ever came to form such concepts. A modern person can

only say, “Well, of course, the ancient Orientals had lively imaginations;

they developed all that fantasy.” We ourselves must marvel that

such a person has not the slightest idea how little imagination a primitive

human being has, what a minor role it plays, for instance, among peasants.

In this respect the mythologists have done wonders! They have invented

the stories of simple people transforming the drifting clouds, the wind

driving the clouds, and so on, into all sorts of beings. They have no

idea how the earlier humanity to whom they attribute all this were really

constituted in their souls, that they were as far removed as could possibly

be from such poetic fashioning. The fantasy really exists in the circles

of the mythologists, the scholars who think out such things. That is

the real fantasy!

What people suppose to have

been the origin of mythology is pure error. They do not know today to

what its words and concepts refer. Certain, may I say, clear hints concerning

their interpretation are therefore no longer given any serious attention.

Plato pointed very precisely to the fact that a human being living here

in a physical body has remembrance of something experienced in the spiritual

world before this physical life. But present-day philosophers can make

nothing of this Platonic memory-knowledge; for them it is something

that Plato too had imagined. In reality, Plato still knew with certainty

that the Greek soul was predisposed to unfold in itself what it had

experienced in the spiritual world before birth, though it still possessed

only the last residue of this ability. Anyone who between birth and

death perceives only by means of his physical body and who works over

his perceptions with a present-day intellect, cannot grant any rational

meaning to observations that have not even been made in a physical body

but were made between death and a new birth. Before birth human beings

were in a world in which they could speak of Jaldabaoth who rose up

in pride, whose mother admonished him, who summoned the six co-workers.

That is a reality for the human being between death and a new birth,

just as plants, animals, minerals, and other human beings are realities

for him here in this world, about which he speaks when he is confined

in a physical body. The Gnosis contained what was brought into this

physical world at birth; and it was possible to a certain extent up

to the Egypto-Chaldean epoch, that is, up to the eighth century before

the Christian era, for human beings to bring very much with them from

the time they had spent between death and a new birth. What was brought

in those epochs from the spiritual world and clothed in concepts, in

ideas, is the Gnosis. It continued to exist in the Greco-Latin epoch,

but it was no longer directly perceived; it was a heritage existing

now as ideas. Its origin was known only to select spirits such as Plato,

in a lesser degree to Aristotle also. Socrates knew of it too, and indeed

paid for this knowledge with his death.

Now what were the conditions

in this Greco-Latin age in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch? Only meager

recollections of time before birth could now be brought over into life,

but something was brought over, and in this Greek period it was still

distinct. People today are inordinately proud of their power of thinking,

but actually they can grasp very little with it. The thinking power

that the Greeks developed was of a different nature. When the Greeks

entered earthly life through birth, the images of their experiences

before birth were lost; but the thinking force that they had used before

birth to give an intelligent meaning to the images still remained. Greek

thinking differed completely from our so-called normal thinking, for

the Greek thinking was the result of pondering over imaginations that

had been experienced before birth. Of the imaginations themselves little

was recalled; the essential thing that remained was the discernment

that had helped a person before birth to find his way in the world about

which imaginations had been formed. The waning of this thinking power

was the important factor in the development of the fourth post-Atlantean

period, which continued, as you know, into the fifteenth century of

the Christian era.

Now in this fifth epoch

the power to think must again be developed, out of our earthly culture.

Slowly, haltingly, we must develop it out of the scientific world view.

Today we are at the beginning of it. During the fourth post-Atlantean

period, that is, from 747 B.C. to 1413 A.D. — the Event of Golgotha

lies between — there was a continual decrease of thinking power.

Only in the fifteenth century did it begin slowly to rise again; by

the third millennium it will once more have reached a considerable height.

Of our present-day power of thought mankind need not be especially proud;

it has declined. The thinking power, still highly developed, that was

the heritage of the Greeks shaped the thoughts with which the gnostic

pictures were set in order and mastered. Although the pictures were

no longer as clear as they had been for the Egyptians or the Babylonians,

for example, the thinking power was still there. But it gradually faded.

That is the extraordinary way things worked together in the earliest

Christian centuries.

The Mystery of Golgotha

breaks upon the world. Christianity is born. The waning thinking power,

still very active in the Orient but also reaching over into Greece,

tried to understand this event. The Romans had little understanding

of it. This thinking power tried to understand the Event of Golgotha

from the standpoint of the thinking used before birth, the thinking

of the spiritual world. And now something significant occurred: this

gnostic thinking came face to face with the Mystery of Golgotha. Now

let us consider the gnostic teachings about the Mystery of Golgotha,

which are such an abomination to present-day, especially Christian,

theologians. Much is to be found in them from the ancient atavistic

teachings, or from teachings that are permeated by the ancient thought-force;

and many significant and impressive things are said in them about the

Christ that today are termed heretical, shockingly heretical. Gradually

this power of gnostic thought declined. We still see it in Manes

[

Note 9 ]

in the third century, and we still see it as it passes over

to the Cathars — downright heretics from the Catholic point of

view: a great, forceful, grandiose interpretation of the Mystery of

Golgotha. This ebbed away, strangely enough, in the early centuries,

and people were little inclined to apply any effort toward an understanding

of the Mystery of Golgotha. These two things, you see, were engaged

in a struggle: the gnostic teaching, wishing to comprehend the Mystery

of Golgotha through powerful spiritual thinking; and the other teaching,

that reckoned with what was to come, when thought would no longer have

power, when it would lack the penetration needed to understand the Mystery

of Golgotha, when it would be abstract and unfruitful. The Mystery of

Golgotha, a cosmic mystery, was reduced to hardly more than a few sentences

at the beginning of the

Gospel of St. John,

telling of the

Logos, of His entrance into the world and His destiny in the world,

using as few concepts as possible; for what had to be taken into account

was the decreasing thinking power.

Thus the gnostic interpretation

of Christianity gradually died out, and a different conception of it

arose, using as few concepts as possible. But of course the one passed

over into the other: concepts like the dogma of the Trinity were taken

over from gnostic ideas and reduced to abstractions, mere husks of concepts.The

really vital fact is this, that an inspired gnostic interpretation of

the Mystery of Golgotha was engaged in a struggle with the other explanation,

which worked with as few concepts as possible, estimating what humanity

would be like by the fifteenth century with the ancient, hereditary,

acute thinking power declining more and more. It was also reckoning

that this would eventually have to be acquired again, in elementary

fashion, through the scientific observation of nature. You can study

it step by step. You can even perceive it as an inner soul-struggle

if you observe St. Augustine,

[

Note 10 ]

who in his youth became acquainted with gnostic Manichaeism, but could

not digest that and so turned away to so-called “simplicity,”

forming primitive concepts. These became more and more primitive. Even

so, in Augustine there appeared the first dawning light of what had

again to be acquired: knowledge starting from man, from the concrete

human being. In ancient gnostic times one had tried to reach the human

being by starting from the world. Now, henceforth, the start must be

made from man: knowledge of the world must be acquired from knowledge

of the human being. This must be the direction we take in the future.

I explained this here some time ago and tried to point to the first dawning

light in humanity. One finds it, for instance, in the Confessions

of St. Augustine — but it was still thoroughly chaotic. The

essential fact is that humanity became more and more incapable of taking

in what streamed to it from the spiritual world, what had existed among

the ancients as imaginative wisdom and then was active in the Gnosis,

what had evoked the power of acute thinking that still existed among

the Greeks. Thus the Greek wisdom, even though reduced to abstract concepts,

still provided the ideas that allowed some understanding of the spiritual

world. This then ceased; nothing of the spiritual world could any longer

be understood through those dying ideas.

A man of the present day

can easily feel that the Greek ideas are in fact applicable to something

entirely different from that to which they were applied. This is a peculiarity

of Hellenism. The Greeks still had the ideas but no longer the imaginations.

Especially in Aristotle this is very striking. It is very singular.

You know there are whole libraries about Aristotle, and everything concerning

him is interpreted differently. People even dispute whether he accepted

reincarnation or pre-existence. This has all come about because his

words can be interpreted in various ways. It is because he worked with

a system of concepts applicable to a supersensible world but he no longer

had any perception of that world. Plato had much more understanding

of it; therefore his system of concepts could be worked out better in

that sense. Aristotle was already involved in abstract concepts and

could no longer see that to which his thought-forms referred. It is

a peculiar fact that in the early centuries there was a struggle between

a conception of the Mystery of Golgotha that illuminated it with the

light of the supersensible world, and the fanaticism that then developed

to refute this. Not everyone saw through these things, but some did.

Those who did see through them did not face them honestly. A primitive

interpretation of the Mystery of Golgotha, an interpretation that was

rabid about using only a few concepts, led to fanaticism.

Thus we see that supersensible

thinking was eliminated more and more from the Christian world conception,

from every world conception. It faded away and ceased. We can follow

from century to century how the Mystery of Golgotha appeared to people

as something tremendously significant that had entered earth evolution,

and yet how the possibility of their comprehending it with any system

of concepts vanished — or of comprehending the world cosmically

at all. Look at that work from the ninth century,

De Divisione Naturae by Scotus Erigena.

[

Note 11 ]

It still contains pictures of a world evolution, even though the pictures

are abstract. Scotus Erigena indicates very beautifully four stages of a

world evolution, but throughout with inadequate concepts. We can see

that he is unable to spread out his net of concepts and make intelligible,

plausible, what he wishes to gather together. Everywhere, one might

say, the threads of his concepts break. It is very interesting that

this becomes more noticeable from century to century, so that finally

the lowest point in the spinning of concept-threads was reached in the

fifteenth century. Then an ascent began again, but it did not get beyond

the most elementary stage. It is interesting that on the one hand people

cherished the Mystery of Golgotha and turned to it with their hearts,

but declared that they could not understand it. Gradually there was

a general feeling that it could not be understood. On the other hand

the study of nature began at the very time when concepts vanished. Observation

of nature entered the life of that time, but there were no concepts

for actually grasping the phenomena that were being observed.

It is characteristic of

this period, at the turn of the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean epoch,

halfway through the Middle Ages, that there were insufficient concepts

both for the budding observation of nature and for the revelations of

saving truths. Think how it was with Scholasticism in this respect:

it had religious revelations, but no concepts out of the culture of

the time that would enable it to work over these religious revelations.

It had to employ Aristotelianism; this had to be revived. The Scholastics

went back to Hellenism, to Aristotle, to find concepts with which to

penetrate the religious revelations; and they elaborated these with

the Greek intellect because the culture of their own time had no intellect

of its own — if I may use such a paradox. So the very people who

worked the most honestly, the Scholastics, did not use the intellect

of their time, because there was none, none that belonged to their culture.

It was characteristic of the period from the tenth to the fifteenth

century that the most honest of the Scholastics made use of the ancient

Aristotelian concepts to explain natural phenomena; they also employed

them to formulate religious revelations. Only thereafter did there rise

again, as from hoary depths of spirit, an independent mode of thinking

— not very far developed, even to this day — the thinking

of Copernicus and Galileo. This must be further developed in order to

rise once more to supersensible regions.

Thus we are able to look

into the soul, into the ego, so to speak, of Christianity, which had

merely clothed itself with the Jewish soul, the Greek spirit, and the

Roman body. This ego of Christianity had to take into account the dying-out

of supersensible understanding, and therefore had to permit the comprehensive

gnostic wisdom to shrink, as it were — one may even say, to shrink

to the few words at the beginning of the Gospel of John. For

the evolution of Christianity consists essentially of the victory of

the words of St. John's Gospel over the content of the Gnosis. Then,

of course, everything passed over into fanaticism, and gnosticism was

exterminated, root and branch.

All these things are linked

to the birth of Christianity. We must take them into consideration if

we want to receive a real impulse for the consciousness of humanity that

must be developed anew, and an impulse for the new Christmas thought. We

must come again to a kind of knowledge that relates to the supersensible.

To that end we must understand the supersensible force working into

the being of man, so that we may be able to extend it to the cosmos.

We must acquire anthroposophy, knowledge of the human being, which will

be able to engender cosmic feeling again. That is the way. In ancient

times man could survey the world, because he entered his body at birth

with memories of the time before birth. This world, which is a likeness

of the spiritual world, was an answer to questions he brought with him

into this life. Now the human being confronts this world bringing nothing

with him, and he must work with primitive concepts like those, for

instance, of contemporary science. But he must work his way up again;

he must now start from the human being and rise to the cosmos. Knowledge

of the cosmos must be born in the human being. This too belongs to a

conception of Christmas that must be developed in the present epoch,

in order that it may be fruitful in the future.

|