FIFTH LECTURE

30th June, 1924

You will have been able

to see how certain abnormalities in the life of the soul which we can

recognise as symptoms of the oncoming of illness, show themselves in

children in a rather undefined form, developing only later in a more

definite manner. I was able to show you, for instance, how what later

on becomes hysteria manifests in early childhood in a manner that is

peculiar to that period, the abnormality remaining as yet quite

undefined. In order however to be able to come to correct conclusions

in regard to abnormalities that belong to childhood, we must also

bear in mind the whole connection that exists between the pre-natal

life (which may be said to carry into the physical life on earth the

impulse of karma) and the gradual development of the child through

the first two epochs — even perhaps also through the third.

Today we shall still

continue to speak, by way of preparation, of general principles; then

we shall be able afterwards to add what further needs to be said,

with practical examples in front of us. For tomorrow morning Frau Dr.

Wegman will put at our disposal a boy whom we have had here under

treatment for some considerable time, and in whom we shall be able to

demonstrate a condition that is strikingly typical.

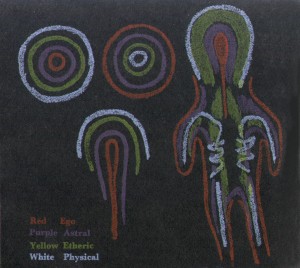

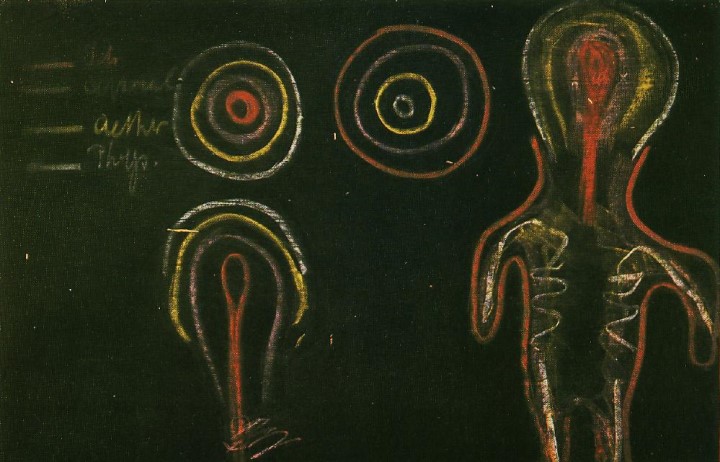

And now in order to

make clear to you something that you will need to know before seeing

this boy, I should like to draw for you here a sketch of the human

organism, in its totality.

| |

Figure 1

Click image for large view |

That there be no confusion, I will always

draw the ego organisation red, then the astral organisation

purple, the etheric organisation yellow, and lastly, the

physical organisation white. And now let us be quite clear and

exact in our thinking, and do our best to grasp the matter as

accurately as possible. For the human organisation is not of such a

nature that we can say: There is the ego organisation, there

the astral organisation, there the etheric organisation,

and so on. We must rather think of it in the following way. Picture

to yourselves a being (see circles above, in the middle) organised in

such a way that there is first of all, on the outside, the ego

organisation (red); then, further inwards, the astral organisation

(purple), then the etheric (yellow), and then the physical (white).

You will have thus a being who shows his ego organisation outside,

while he drives the astral organisation farther in, the etheric still

farther in and the physical organisation farthest in of all.

And now, beside it, we

will draw a different arrangement, where we have the ego organisation

right inside (red), the astral organisation, as it were, raying

outwards (purple); then, farther out, the etheric organisation

(yellow), and still farther out, the physical organisation (white).

We have now before us two beings that are the direct polar opposite

of one another. Look at them carefully. As you see, the second being

(on the left) will present, on the outside, a strong physical

organisation, into which plays also the etheric organisation, whilst

the astral and ego organisations tend to disappear within. But now,

these conditions being given, a change can come about. The

configuration of the being I have sketched here (on the left) may be

modified in the following way

(see

Figure 1,

left below).

Here the physical organisation (white)

may be fully developed above, while below it is

unfinished, left open. Then we can have the etheric organisation

(yellow), somewhat stronger here below than the physical, yet still

unfinished. And we can have here the astral organisation (purple)

coming down more in a sweeping curve; and, finally, the ego

organisation (red) descending like a kind of thread. What we sketched

before diagrammatically in the form of a sphere can quite well

manifest also in this way.

To make the matter

still clearer, I will draw this last figure here once again

(see upper part of

Figure 1,

right)

— the ego organisation (red), the astral organisation (purple), and

ether organisation (yellow) and the physical organisation (white).

And now we will add on to it below, the other being (figure in

the middle, above) and we will do it in the following way. To begin

with, for the ego organisation, which is outside, instead of

describing a circle, as I did before, I will let the circle break and

bend, so that we have this kind of form

(red, on the lower part of

Figure 1,

on the right).

As a matter of fact, this is what is continually happening with the

sphere and the circle, wherever they occur in Nature — indeed,

in the whole universe. Owing to the plasticity that is everywhere

present, the sphere and the circle are perpetually undergoing

modification in their form, being moulded and turned in various ways.

Going inwards, I shall have to show next the astral organisation

(purple); farther in, the ether organisation (yellow); and finally —

pushed right inside, as it were — the physical organisation

(white).

So now you have our

second being changed into the head of man, and our first changed into

the metabolism-and-limbs system. And in fact, this is how things

really are in man. In the head organisation the ego hides itself

right inside, the astral body is also comparatively hidden, while

outside, showing form and shape, are the physical body and the ether

body, giving form also to man's countenance. In the

metabolism-and-limbs system, on the other hand, the ego is on the

outside, vibrating all over the organism in its sensibility to warmth

and to touch. Proceeding inwards from the ego, we have then the

astral body vibrating in an inward direction; farther in, it all

becomes etheric; and finally, inside the bones, it becomes physical.

We go therefore

outwards from ego to physical body in the head organisation;

the arrangement there is centrifugal. In the metabolism-and-limbs

system, it is centripetal; we go here inwards from ego to

physical. And the arrangement in the rhythmic system, in between the

two, is in perpetual flow and interchange, so that one simply cannot

say whether it is going from without inwards or from within outwards.

For the rhythmic system is, in fact, half head system and half

metabolism-and-limbs system. When we breathe in, it is more

metabolism-and-limbs system; when we breathe out, it is more head

system. The relationship between systole and diastole is expressed in

the fact that the head system is to the limb system as outbreathing

is to inbreathing. We carry therefore in us, you see, two directly

opposite beings — mediated by the middle part of our organism,

the rhythmic organism. What follows from this? A result, that is of

no little importance.

Suppose we receive

something through the medium of our head — as we do, for

instance, when we listen to what another person is saying. Having

been received by our head, it goes first into the ego, and into the

astral body. But an interplay is always taking place in man's

organism, and the moment something is caught and held fast, by means

of an impression received in the one ego organisation (here in the

head), it immediately vibrates right through into the other ego

organisation (below). And then the same thing happens the moment

something strikes home into the astral organisation; that too

vibrates right through into the other astral organisation. If it were

not so, we would have no memory. We owe our memory to the fact that

all the impressions we receive from the external world have their

reflections, their mirror-pictures, in the metabolism-and-limbs

organisation. If I receive an impression from without, it disappears

from the head organisation — which, as we have seen, is

centripetally arranged, from physical on the outside to ego within.

For the ego must maintain itself, it must hold its own. It cannot

carry one single impression for hours on end; if it did, it would

have to identify itself with the impression. No, it is down below

that the impressions are preserved; and they have to make their way

up again, for us to “remember” them.

But now, it may quite

well happen that the whole of the lower system, which is, as we have

seen, in direct polar contrast to the upper system, is

constitutionally weak. In that case, when impressions occur, the

impressions do not stamp themselves deeply enough into the lower

system. The ego, let us say, receives an impression. If everything

were normal, the stamp of the impression would be passed on to the

lower system and only in the event of memory be fetched up again. If

however the system down below, and in particular, the ego

organisation — which covers there the whole periphery —

is too weak, so that the impressions do not stamp themselves strongly

enough, then the impressions that fail to sink down into the ego

organisation of the lower system, keep streaming back again into the

head.

We have with us a child

who is constituted just in this way. One day we showed him, for the

first time, a watch. It interested him. But his limb organisation is

weak; consequently, the impression does not sink down, but rays back

again. I sit down by this child, and begin to talk to him. All the

time he is perpetually saying: “Lovely watch!” Hardly

have I said a few more words than he says again: “A lovely

watch!” The impression keeps coming back. In the education of

children we must pay attention to such tendencies, of which there may

sometimes be only very faint indications, but which are nevertheless

quite important. For if we do not succeed in strengthening the too

weak metabolism-and-limbs organisation, then this “streaming

back” of impressions will go on happening with greater and

greater intensity, and in later life the patient will suffer from the

type of paranoia that is associated with fixed ideas. He will

suffer from firmly fixed ideas. He will know that these ideas have no

business to take up their abode, as it were, in his soul in this

persistent way, but he will not be able to dismiss them. Why can he

not dismiss them? Because while, up there above, there is the

conscious soul-life, the unconscious, down below, is out of

control; it keeps pushing certain ideas back into consciousness,

which then become fixed ideas.

We said that the boy

has a metabolism-and-limbs system that is too weakly developed. What

does this mean? When metabolism and limbs are too weakly developed,

the albumen substance in the human organism is prevented from

containing the right amount of sulphur. We then have a

metabolism-and-limbs system which produces albumen that is poor in

sulphur. This can quite well happen; the proportion in which the

constituents are combined in the albumen is, in such a case,

different from what is usual. And, in consequence, we have in the

patient what I have just been describing — fixed ideas,

beginning to announce themselves in the organism in the years of

childhood.

But now the opposite

condition may also arise. The system of metabolism and limbs may be

so constituted that it is too strongly attracted to sulphur. The

albumen will then be too rich in sulphur. It will have in it carbon,

oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, and — in proportion — too

much sulphur. In a metabolism-and-limbs system of this kind —

for the system is influenced in its manifestations by the particular

combination of the substances within it — there will not be, as

before, the urge to push everything back; but, on the contrary, in

consequence of the albumen being too rich in sulphur, the impressions

will be absorbed too powerfully, they will nest themselves in too

strongly.

Note that this is a

different condition from the one I described in an earlier lecture,

where there is a congestion at the surface of an organ. That

condition gives rise, as we saw, to fits. It is not congestion

that we have now, but a kind of absorption of the impressions: the

impressions are, as it were, sucked in — and consequently

disappear. We bring it about that the child has impressions, but to

no purpose; impressions of a particular nature simply disappear into

the oversulphurous albumen. And only if we can succeed in getting

these impressions back, in drawing them out again from the sulphurous

albumen — only then shall we be able to establish a certain

balance in the whole organism of spirit, soul and body. For the

disappearance of the impressions in the sulphurousness of the

metabolism-and-limbs system induces a highly unsatisfactory condition

of soul; it has a disturbing, exciting effect. The whole organism is

a little agitated, a slight tremor runs through it.

As you know, I have

often said that Psycho-Analysis is dilettantism “squared”,

because the Psycho-Analyst has no real knowledge of soul or spirit or

body — nor of ether body; he does not know what it is that is

taking place, all he can do is to describe. And since this is all he

can do, he is quite content simply to say: “The things have

disappeared down below; we must fetch them up again.” The

strange thing is, you see, that materialism is quite unable to probe

thoroughly into the qualities even of matter! Otherwise it

would be known that the disappearance of the impressions is due to

the fact that the albumen-substance in the will organism contains too

much sulphur. Only by following the path of Spiritual Science can the

nature and character of physical substance be discovered.

It would be good if

those who have to educate abnormal children would learn to have an

eye for whether a child is rich or poor in sulphur. We shall, I hope,

be able to speak together of many different forms of soul

abnormalities, but you ought really to come to the point where

certain symptoms indicate of themselves the main direction in which

you have to look for the cause of the trouble. Suppose I have a child

to educate, in whom I observe that impressions make difficulties for

him. This may, of course, be due to conditions described in the

previous lectures. But if I am right in attributing it to the

condition we have been describing today, then how am I to proceed?

To begin with, I look

at the child. (The first thing is, of course, to know the child,

to make oneself thoroughly acquainted with him; that is the first

essential.) I look at him, and notice one of the most superficial of

symptoms, namely, the colour of his hair. If the child has black

hair, I shall not take the trouble to investigate whether he be rich

in sulphur, for a child who has black hair certainly cannot be rich

in sulphur, though it is possible he may be poor in sulphur. If,

therefore, abnormal symptoms are present, I shall have to look for

their cause in some other sphere. Even if recurring ideas show

themselves, I shall nevertheless, in the case of a child with black

hair, have to look for the cause elsewhere than in richness of

sulphur. If however I have to do with a fair-haired or red-haired

child, I shall look for signs of overmuch sulphur in the albumen.

Fair hair is the result of overmuch sulphur, black hair comes from

the iron in the human organism. It is indeed the case that so-called

abnormalities of soul and spirit can be followed right into the

physical substance of the organism.

Now, let us take a

little volcano of this kind, a sulphurous child, who sucks down

impressions into the region of the will, where they stiffen and

cannot get out. We shall very quickly be able to detect this in the

child. He will be subject to states of depression and melancholy. The

hidden impressions that he carries inside him are a torment to him.

We must raise them to the surface, and we must go about it, not with

psycho-analysis as it is understood today, but with a true and right

psycho-analysis. We must observe the child and find out what kind of

thing it is that is inclined to disappear in him. In the case of a

child who confronts us on the one hand with inner excitement and on

the other hand outwardly with a certain apathy, we shall have to

watch carefully until we can ascertain quite exactly what things he

remembers easily and what things he lets disappear within him. Things

that do not come back to him, we should bring before him repeatedly,

again and again, and as far as possible in rhythmic sequence. A great

deal can be done in this direction, and often in a far simpler way

than people imagine. Healing and education — and the two are,

as you know, nearly related — do not depend so much on

concocting all kinds of mixtures — be they physical or

psychical! — but on knowing exactly what can really help.

What is important,

then, is to be able to know in any particular case what particular

substance is required; we must really succeed in following the path

that brings us to that knowledge.

In my experience in the

Waldorf School I have often come across children who seem, in a way,

quite apathetic, but at the same time show signs also of being

inwardly in a state of excitement. We had, for instance, in Herr K's

Class, a particularly odd little person. He was at once excited and

apathetic. He has by now improved considerably. When he was in the

third class — he is now in the fifth — his apathy showed

itself in the fact that it was not easy to teach him anything; he

never took anything in, he learned only very slowly and with

difficulty. But scarcely had Herr K. turned away from him and begun

to bend over another child in front, than up would jump this little

spark and hit him smack on the back! The boy was, you see, at one and

the same time — inwardly, in his will, like quicksilver

and intellectually an apathetic child.

There are, in fact,

quite a number of children who have this kind of disposition, in

greater or less degree; and it is important to note that in such

children the capacity for absorption of external impressions is as a

rule limited to impressions of a particular kind or type. If we have

the right inspiration — and it will come, once we have the

right disposition of mind and soul — we shall find for the

child a certain sentence, for example, and bring it before him,

suggest it to him. This can work wonders. It is only a question of

guiding the whole activity and exertions of the child, of turning

them in a certain direction. But this the teacher must achieve; and

he can easily do so, provided he does not try to be too clever, but

rather to live in such a way that the world, as it were, lies open to

his view; he should not ponder overmuch about the world, but “behold”

it, as it shows itself to him.

Think how boring it is

— and what I am about to say is something you need to take

seriously if you want to educate abnormal children — only think

how tedious it is to have to go through life with no more than a

handful of concepts! The soul-life of many people today is terribly

barren and tedious, just because they are forced to get along with a

very few concepts. With so small a range of concepts mankind slides

all too easily into decadence. How hard it is for a poet today to

find rhymes; all the rhymes have been used before! It is the same in

the other arts; on every hand we have echoes and reminders of the

past, or there is nothing new left to be done. Look at Richard

Strauss, who is now so famous — and at the same time so

severely criticised. He has made all kinds of innovations in

orchestral music, merely in order to avoid repeating eternally the

same old things.

But now think, on the

other hand, what an interesting time you could have if you set out to

study, let us say, every possible form of nose! Each person has a

different nose; and if you were to learn to be observant and to have

a quick perception for all the various forms of nose, you would soon

begin to have variety in your mental content, and it would then be

possible also for your concepts to become inwardly alive, you would

be continually moving from one to another. I have taken the nose

merely as an example, of course. Through developing an intelligent

feeling for form as such, for all the variety of form that

lies open to our perception, we shall actually be cultivating a

disposition of soul that will enable us to receive inspiration when

the occasion requires.

As you live your way

into this beholding of the world — not a thinking about, but a

real beholding of the world — you will find that, if you have a

child who is inwardly sulphurous, alert and active, but outwardly

apathetic, then, through your being able to behold him, something

will suggest itself to you in connection with him and his special

constitution, that provides you with the right idea. You will perhaps

feel: I must say to him every morning: “The sun is shining on

the hill” — or it can be some other sentence; it can be

quite a simple, everyday sentence. What matters is that it comes to

him rhythmically. When something of this kind is brought to

the child rhythmically, approaching him as it were from outside, then

all the sulphurous element in him is unburdened, it becomes freer.

So, with these children — who should indeed be protected in the

tender years of childhood, lest later on they become the pet victims

of Psycho-Analysts — with these children we shall achieve a

great deal if we reckon especially with their rhythmic nature, and

let some such sentence be imparted to them so that it comes to them

from outside again and again, rhythmically.

It is, in fact, very

good to make a regular practice of this with all children. It works

beneficially. In the Waldorf School we have arranged that school

begins with a verse which, as it were, saturates the life of thought,

day after day, in rhythmic sequence. And where you have a case of

overabsorption in the organism, this practice will definitely help to

bring relief.

We shall be doing the

right thing for abnormal children, if we bring them together in

groups every morning. If we have only a small number of children, we

can of course, at any rate to begin with, take them all together.

Something quite wonderful can come out of this. Let the children

repeat a verse that is in the nature of a prayer, even though there

may be some among them who cannot say a word; you will find this

repeating in chorus has a wonderful balancing influence. And

particularly in the case of a child in whom impressions tend to

disappear, will it be important to induce certain impressions by

means of such rhythmical repetition. You can change the impressions,

say every three or four weeks, but you must continue bringing them to

the child again and again. This will have the result of relieving the

internal condition; it can indeed happen that the albumen gradually

ceases to have an excess of sulphur-content. How is one to explain

this? The trouble is, as we have seen, that the internal parts of the

child are not giving back the impressions; that is to say, the

movement from below upwards is too weak, it is even negative. If now

we bring in a strong impulse from above, we rouse the

movement from below (that is weak) to a stronger activity.

Suppose, however, we

have the opposite state of affairs. Suppose we have children who

already begin to show a tendency to fixed ideas. The raying back of

impressions is in these children too strong; there is too little

sulphur in the plasma. Here we shall have to do the contrary of what

we did before. When we observe that the same sentence, the same

impression is perpetually coming again and again to the child, it

will be helpful if we ourselves fabricate for him a new impression

(one which our instinct tells us may be right for this child) and

then bring it to him in a gentle whisper, murmuring it softly in his

ear.

The treatment could,

for example, take the following form. The teacher says: “Look,

there's red!” The child: “It's a lovely watch!”

Teacher: “But you must look at the red.” Child:

“A lovely watch!” And now we try repeating, each time a

little more softly, a new impression which has the effect of

paralysing the first. We say very softly: “Forget the watch! —

Forget the watch! — Forget the watch!” Whispering to the

child in this way, you will find that you gradually whisper away the

fixed idea; as you whisper more and more softly, the fixed idea

begins to yield, it too grows fainter and fainter. The remarkable

thing is that when the idea is spoken — when the child

hears it spoken — it is more weakly thought; it

gradually quietens down, and at length the child gets the better of

it. So we have this method too that we can use; and, as a matter of

fact, very good results can be achieved with a treatment of this

simple nature.

If only such things

were known! Think how it is in an ordinary school. You have a class,

and in this class are children who already have a tendency, though

perhaps only slight, to fixed ideas. They are not transferred to

special classes for backward children, they continue in their own

class. And now perhaps there is a teacher who has a voice like

thunder, who shouts loud enough to make the walls fall down. Later

on, these children will turn into crazy men and women, suffering from

fixed ideas. It would never have happened, had the teacher only known

that he should at times speak more quietly, that he ought really to

whisper certain things softly to the children. So very much depends

on the manner in which we meet the children and deal with them!

Then, of course, in

cases of this kind, the psychical treatment can be combined quite

simply with ordinary therapy. If we have a child in whom impressions

tend to disappear, it will be good to set out with the definite

resolve to combat in this child the strong tendency he has to develop

sulphur in the albumen. We can make good headway in this direction by

seeing to it that the child has the right kind of nourishment. If,

for instance, we were to give him a great deal of fruit, or food that

is prepared from fruit, we should be nurturing and fostering his

sulphurous nature. If, on the other hand, we give him a diet that is

derived from roots, and contains substances that are rich, not in

sugar, but in salt, then we shall be able to heal such a

child. Naturally, this does not mean we are to sprinkle his food

copiously with salt, but we should give him foods in which salt is

contained — as it were, in already digested form. You will find

that you can discover methods of this kind by learning to pay

attention to things that are actually going on all the time in the

world around you. (Here Dr. Steiner related a fact that he had

himself observed, namely, that the population of a certain district

instinctively preferred a particular diet, which worked

counter to an illness that was prevalent in that district.) And so,

in the case of these children, instead of leaving them to become

subjects later on for the Psycho-Analyst, it would be far better if

we were to give them in early childhood a diet that suits their need

— a diet, that is, consisting of rather salty food.

Take now the opposite

case — children who fail to absorb impressions, children in

whom the impressions stream back. These children are poor in sulphur,

and the best treatment for them is to give them as much fruit as

possible; they will soon acquire a taste for it and enjoy eating it.

If their condition has become decidedly pathological, we should try

also to bring fragrance and aroma into their food; they should have

fruits that smell sweetly. For aroma contains a strong sulphurous

element. And for a very serious case, we shall have to administer

sulphur direct. This can show you once again how from a spiritual

study of the conditions, we are led straight on to the therapy that

is required. But it must be spiritual study; it will never do

to rest content with the mere description of phenomena; that will get

us no further than symptomatology. What we have to do is to try to

penetrate, in the way I have shown you, right into the inner

structure and texture of the organism.

We have been

considering irregularities which can occur in the human being when

the lower part of him is not in right accordance with the upper part,

so that the impressions which the head organisation receives above,

fail to find the right resonance in the metabolism-and-limbs

organisation. But now the condition is also possible where throughout

the human being as a whole, ego organisation, astral organisation and

etheric-physical organisation do not fit well together, do not

harmonize. The physical organisation, let us say for example, is too

dense. The child will then be absolutely incapable of sinking his

astral body into this densified physical organisation. He will

receive an impression in the astral body, and the astral body can

stimulate the corresponding astrality of the metabolic system, but

the stimulation is not passed on to the ether body, least of all to

the physical. We can recognise this condition in a child by noticing

how he reacts if we say to him: “Take a few steps forward.”

He will not be able to do it. He does not rightly understand what he

has to do. That is, he understands quite well the words we say, but

he does not convey their meaning to his legs; it is as though the

legs did not want to receive it. If we find this — that the

child is in difficulties when we tell him to do something which

involves the use of his legs, that he hesitates to bring his legs

into movement at all — then that is for us a first sign that

his physical body has become too hardened and is unwilling to receive

thoughts; the child, in fact, shows indications of being

feeble-minded. Since in such conditions the body bears too

heavily on the soul, we shall find that moods of depression and

melancholy also occur.

On the other hand, if a

child's legs never wait for a command, but are perpetually wanting to

run about, then we have in that child a tendency to a condition of

mania. The tendency need only show itself very slightly, to

begin with, but it is in the legs that we shall notice it first of

all. It is accordingly most important that we should always include

in our field of observation what a child does with his legs —

and also with his fingers. A child who likes best to let his hands

and legs — for you can notice the same thing in the hands —

hang about anyhow, flop on to things, has the predisposition to be

feeble-minded. A child who is perpetually moving his fingers,

catching hold of everything, kicking out in all directions with his

feet, is predisposed to become maniacal, and possibly violent.

But now these symptoms

that are so marked in the limbs can be observed in all activities. In

activities that are more connected with the spiritual and mental,

they show themselves in a slighter form, and yet here too they are

quite characteristic. In many children, for instance, you may be able

to notice something like the following. A child acquires a knack of

doing something with his hands. Let us say, he learns to draw a face

in profile. And now, he simply cannot stop himself; whenever he sees

anyone, he immediately wants to draw his profile. It becomes quite

mechanical. This is a very bad sign in a child. Nothing will persuade

him out of it. If he is just about to draw a profile, I can talk to

him as much as ever I like, I can even offer him a sweet — he

goes on just the same, the profile must be drawn! This is connected

with the maniacal quality that develops when intellect runs to

excess. The reverse of this — namely, the urge to do nothing,

even when all the conditions are there ready, the urge not to let the

thought go over into work and action — is connected with the

feeble-mindedness that may be imminent.

All this goes to show

that by learning to bring the limbs into proper control, we can do

much to counteract on the one hand feeble-mindedness, and on the

other hand the tendency to mania. And here the way is marked out for

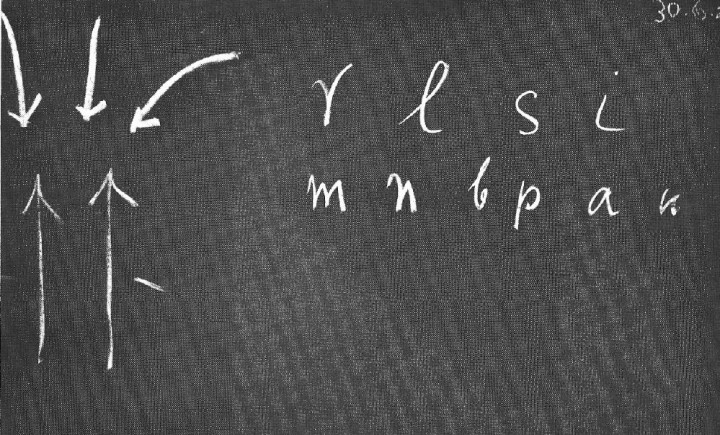

us at once to Curative Eurythmy. [For

the relation of Curative Eurythmy to Eurythmy as Art see end of

Lecture 12.] In the case of a feebleminded child, what

you have to do is to bring mobility into his metabolism-and-limbs

system; this will stimulate also his whole spiritual nature. Let such

a child do the movements for R, L, S, I (ee), and you will see what a

good effect it will have. If, on the other hand, you have a child

with a tendency to mania, then, knowing how it is with his

metabolism-and limbs system, you will let him do the movements

for M, N, B, P, A (as in Father), U (as in Ruth), and again you will

see what an influence this will have on his maniacal tendency. We

must always remember how intimate the connection still is in the

young child between physical-etheric on the one hand, and

soul-and-spirit on the other. If we bear this continually in mind, we

shall find our way to the right methods of treatment.

| |

Lecture 1,

Blackboard Image 1

Click image for large view | |

| |

Lecture 1,

Blackboard Image 2

Click image for large view | |