SIXTH LECTURE

1st July, 1924

I

would like, dear friends, to consider today’s lecture as

affording a kind of typical example of how we intend to proceed with

the rest of the course. We may naturally have occasion to extend or

modify our method from time to time. To begin with, we will take as a

basis for our discussion together, the case of a boy who will

presently be brought in. The history of the case is as follows.

The

boy has been with us since 11th September, 1923, and was nine years

old when he came. During the time of pregnancy the mother felt quite

well; in the fifth month she made a tour through Spain. The birth was

very difficult, the child had to be turned and helped out with

forceps. In the first year, he was well and healthy, and there was no

thought at all of abnormality. When six months old, he lay once for a

very long time in the sun, with the result that he was overcome

afterwards with a kind of faintness, followed later by fever. He was

breast-fed for three months only, and from nine months to three years

old was a very poor eater. During all this time he had really no

desire for food at all. In the second summer of his life, the parents

noticed that the boy's eyes were changing and becoming less clear. In

this second year he was also not yet able to speak or to walk; and he

would frequently start screaming and crying at about four o'clock in

the morning, without apparent cause. He developed a habit at this

time that should never be disregarded in children — the habit,

namely, of sucking his thumb. Cardboard splints were on this account

strapped to his elbows, and at night he was made to wear aluminum

shields on his hands. The wearing of the shields was continued for

three years. The boy was all this time backward in his development

and at the age of five was still unable to speak connectedly. Then we

come to the time of the change of teeth, beginning from the seventh

year. The middle teeth have been changed, but the other upper teeth

are not all changed yet. Or has he by now changed some more? Yes, he

has got one new tooth. One of the front teeth is also not yet there.

Yes, I see it has come through. The other was already strongly

developed when he came to us. The mother informs us that the father

too as a child was very late in his development, and the second

dentition was with him also very considerably delayed.

At

the time when he came to us, the boy was in a weak state of health.

He weighed scarcely 53 lb. He has delicate bones, and his hands and

feet are disproportionately large. He is very clumsy with his hands.

External tests all give a negative result. After he came, he showed

signs of increasing restlessness, and grew more and more difficult to

manage. His manners are rather bad. The bodily functions are in good

order.

Since

January of this year, the boy has become decidedly quieter and more

human. The things in the world outside have begun to interest him and

arouse his wonder. A quality is developing in him which we must do

our utmost to encourage — attentiveness to the world around.

I do not mean an attentiveness merely of the intellect, but a

turning with heart and feeling to the things of the world. Things he

sees around him call forth wonder and astonishment in him. Let me

take this opportunity to emphasize that mere intellectual attention

to the world can never work therapeutically; the feeling and the will

must also be engaged. The boy is moreover becoming friendly; whereas

at first he would pass people by with indifference, he now recognises

them again. It is not easy to rouse him to be active in any

way. What he does, he does unwillingly. By January, however, he did

manage to acquire some proficiency in the useful art of knitting.

What is important is that one introduces the child to an occupation

of this kind which on the one hand brings him into mechanical

movement, but yet on the other hand makes him pay attention, for in

knitting one can easily drop a stitch! He likes best of all to play

with a little cart or sledge. He will talk for hours at a time of

nothing but his little cart. That will remind you of the symptom of

which I was speaking yesterday. He is also learning quite quickly to

speak and understand German. There, then, you have the description of

the immediate facts and findings.

And

now, if you will begin to observe the child for yourselves —

(to the boy) Come here a minute! — you will find many things to

notice. Let me draw your attention, first of all, to the strongly

developed lower half of the face. Look at the shape of the nose and

the mouth. The mouth is always a little open. With this symptom is

connected also the peculiar formation of the teeth. It is important

to note these things, for they are unquestionably bound up with the

whole soul-and spirit constitution of the child. We must not make the

mistake of attributing the open mouth to the formation of the teeth;

both are to be traced to a common cause, namely, that in this child

the lower man is not fully under the control and mastery of the upper

man. If you can see that, then much will become clear to you. Imagine

that here you have the upper man, the nerves-and-senses man.

This works upon the whole of the rest of the human being. For, as you

know, this is the part of man that is the most developed in the first

period of life; it brings the most forces with it from the embryonic

time, and during that time had in it the most highly developed

forces. The rest of the body is more or less dependent on what forms

itself here in the upper man. Whereas the lower man forms itself

directly from the constitution of the mother body, the rest of man is

only indirectly dependent on what forms itself here. The formation

you see here in the jaws — the jaws belong, of course, to the

limb system — should be completely taken into the head

system. But in this case the head system is not strong enough to

bring the limb system fully into itself; consequently, external

forces work too powerfully upon this limb-system. Look at a

well-formed human being, where the lower part of the head is in

harmony with the rest of the head. You will be quite right in

concluding that you will find in such a person a nervous system that

is in the highest possible degree master of the metabolism-and-limbs

system. No external forces will in this case exercise undue

influence. If however the head is incapable of controlling the rest

of the body, then the forces that come from without will work too

strongly into the rest of the body. In the child before us, we have

clear evidence of this in the fact that the arms, and also the legs,

have not the proportions they would have if they were brought into

right relation with the upper part of the body, but have grown too

big, because external forces have worked upon them in excess. (Look,

he's amused! I think Fraulein B. was asking him why he keeps his

mouth open, and his reply was: “To let the flies come in.”

This is a firmly fixed opinion of his.)

All

that we have been describing is, you see, due in the first place to a

weakness in the upper part of the organisation. Observe now how the

head is narrow here (in front) on both sides, and pressed

back; so we have in this boy the symptom of narrow-headedness, a sign

that the intellectual system is but little permeated with will. This

part (at the back) expresses strong permeation by the will. The

front part of the head is accessible only to external influences that

come via sense-perception, whereas the back part of the head

is accessible to all manner of influences from without. You have

therefore here a beginning of what manifests so strikingly in the

arms and legs; the brain enlarges and spreads out at the back of the

head.

The

study of such a child can be very interesting; indeed a child like

this is more interesting than many normal children, although many a

normal child is easier and pleasanter to deal with.

Here

(in the front) you have that part of the whole head organisation

which has its substance supplied to it from the rest of the organism.

What is deposited here in the way of substance — not forces,

but substance — is derived entirely from external nourishment.

Here, on the other hand (at the back) substance begins to be

supplied, not from food, but from that which is received through the

breathing, through the senses, etc., and is cosmic in origin. The

back of the head is, as regards substance, of cosmic origin. Here (in

the front) as we remarked, the head is pressed together. In all

probability this points back to a purely mechanical injury, either at

birth or during pregnancy, a mechanical injury in which we can see

nothing else than a working of karma, for it can have no connection

with the forces of heredity. As a result of this compression, the

head tends not to let enough substance get carried up into it from

the food that is eaten as nourishment. For it has anyway no

inclination to start working upon the nourishment that does reach it,

the demand for nourishment being so slight in this front part of the

head. You can see therefore, simply by observing the external form of

the head, that the boy is bound to be at some time quite without

appetite. Here, in this front part of the head, the accumulation of

what is received by way of nourishment begins to be deficient.

The

insufficiency in the control exercised upon the whole limb system has

its influence upon the breathing system. The entire system of the

breath is very little under control, and breathing tends to become

disturbed and uneasy. This is connected with the whole way in which

the lower jaw is formed. The lower jaw receives into itself a great

quantity of air — too much, indeed; with the result that

substance is accumulated in too great measure, both here in the lower

jaw and in the limbs. Hence the symptom that is so conspicuous in a

child of this kind: the inbreathing is not in right relation to the

outbreathing, it is too vigorous as compared with the outbreathing.

Consequently, the boy is unable to develop within him the right and

necessary quantity of carbonic acid; he is deficient in carbonic

acid. So here you have also a clear demonstration of the fact that in

a human being who is deficient in carbonic acid the limb system will

be found to be over-developed; and with the limb system is of course

connected everything in the human being that has fundamentally to do

with movement. What ought to happen is that gradually, in the

course of life, the whole system of movement in man should become a

servant of the intellectual system. (To the boy) Stand still a

minute! And now come here to me and do this! (Dr. Steiner

makes a movement with his arm as if to take hold of something; the

boy does not make the movement.) Never mind! We mustn't force him. Do

you see? It is difficult for him to do anything; he has not the power

to exercise the right control over his metabolism-and-limbs system.

If he had, he would have lifted his arm in the way I showed him. With

this is also connected the lateness of the second dentition. In order

for the change of teeth to go forward in the right way, there must be

a co-operation between senses-and-nerves system and

metabolism-and-limbs system. The working together of the two systems

provides the foundation for the change of teeth. These phenomena are

all closely connected with one another.

And

now what is the result of all this? As we have seen, when the child

was born, and for as long as the metabolism and-limbs system had not

yet developed — as is the case, of course, with a very young

child — he was able to be in control of his body. No one

noticed that there was anything abnormal. Only in course of time,

when he had grown quite a bit, could the abnormality, which was

present all along, show itself. And it is just as we might expect,

that he should attain comparatively late those faculties which depend

on the upper system's having the lower system under control. He was

late, namely, in learning to speak and to walk. What would have been

the right educational treatment for this child in very early years?

Obviously a special effort should have been made to begin with

Curative Eurythmy even before he was able to walk, simply moving his

limbs oneself in eurythmic movements. If this had been done, then the

movements carried out in this way in the limbs would have been

reflected in the nerves-and-senses organism, and since at that early

age everything, is still supple in the child, the form of the head

could actually have grown wider. By beginning in good time to produce

in a child movements that have the right forms, a great deal can be

accomplished for the forming of the head, and one cannot but rejoice

at the results that can be achieved in this direction. In the case of

the boy before us, where the very bones of the skull have been

narrowed by external pressure, it is certainly difficult for the head

to grow any bigger.

During

the time when I was engaged in teaching, an abnormal boy of eleven

and a half years old was given into my care. I have written about him in

The Story of My Life.

The parents and the family doctor

were at their wit's end what to do with this child. He would have to

be put to learn some trade — and that was terrible to

contemplate! With the exception of his mother, who took the matter

quietly, everyone was frantic about it; what a disgrace for a highly

respectable city family to have to put their boy to a trade! To pass

comment or criticism on the matter was not my business. The boy was,

among other things, hydrocephalic. I stipulated that he should be

left entirely to me. His attainments up to that time may be judged

from the fact that he had completely failed a short while before in

the entrance examination for one of the lowest classes in the

“Volksschule”.

[Primary School up to age of fourteen.] All he had done in the

allotted time was to rub a large hole into a copy-book with a piece

of india-rubber. The boy had also the strange and singular habit of

not wanting to eat at all at table, but of eating with great relish

potato skins that had been thrown away as refuse.

After

a year and a half had passed, the boy had progressed so far as to be

able to attend the First Class in the “Gymnasium”.

[Grammar School from age of

eleven or twelve.] The secret of the matter lay in the care

and attention given to the movements of the limbs; through this, it

came about that the hydrocephalic condition disappeared. The head

became smaller — a clear sign that results can be achieved in

this direction. Where, as in the boy before us, the bones of the

skull have been pressed together by a blow from outside, there will,

as I said, be great difficulty in achieving any enlargement of the

head, but some improvement might nevertheless have been attained.

And

now the question is: What guidance can we gain from our observation

of the child, as to how we are to proceed with his education? Of

primary significance for us as educators is the fact that the boy has

had to bring his soul-and-spirit nature into a body whose forces are

not harmoniously developed. Karmic complications lie behind this.

Believe it or not, the boy is a genius. What do I mean by that? (He

doesn't understand what we are saying.) I mean that, in accordance

with his karmic antecedents, he could have been a genius. In the

conditions, however, under which the boy finds himself at the present

day (and he was of course obliged to be born into these conditions)

he has been unable to develop the possibilities that were present in

him by virtue of his antecedents; hence, and to that extent, there is

abnormality. The choice of his parents has clearly had its bearing on

the situation. It has made things difficult for him; he looks out

upon the world under difficult bodily conditions. For he has a body

that has grown hard and rigid, owing to the fact that the forces of

the upper and of the lower man do not interlink properly, do not fit

well together. We have thus to do here with a hardening of the

organism. When the boy wakes up, the astral body and the I

organisation cannot dive down into the organism as they should. They

come up against a kind of brick wall.

But

now man's whole faculty of attention, the ability we possess

to be attentive to the world around us, depends on our being able to

establish the right adjustment between soul-and-spirit on the one

hand and the bodily-physical nature on the other hand. Suppose we are

unable to do this. Then, in so far as we are concerned merely with

the more superficial side of life, the inability to establish the

right adjustment will show itself in clumsiness, in unskilfulness.

Traces of this sort of inability can be observed in the majority of

people today. In my experience — I apologise for the hard

verdict! — most persons are highly unskilful. They find it

difficult to develop skill and deftness. If I go over in my mind all

the eight hundred children we have in the Waldorf School, I cannot

say that any large percentage of them are distinguished for skill and

ingenuity. And wherever you go, you will find evidence that this

inpouring of the astral body and I organisation into the physical

organization does not come off as it should. The reason is to be

sought in the fact that we are now living in the full flower of the

age of intellectualism. The thinking, the mental and spiritual

activity, that belongs to our time, reaches only into the bones —

not into the muscles. And a person who sets out to make use of his

bones does not thereby become skilful! The intellectual system in man

is adapted for making its way into the bony system, but in order to

get the bony system moving, it requires the help of the

muscles; and the ability of the astral body and I organisation to

insinuate themselves into the muscular system is in our time

astonishingly small. How is this? The root of the trouble lies in the

fact that this intellectual age of ours is not devout, is not

genuinely religious in character; the churches of the various

denominations do not really make for deep and sincere religion. But

now, the development of the muscles attached to the bones depends on

the presence in the world of great men who are revered as examples,

as heroes. As soon as a human being can look up, even if only in

thought, to great souls and see in them his pattern and example, then

a right contact begins to be established between his muscular and his

bony systems. And in the boy we are considering, lack of interest has

been from the first a marked characteristic.

And

now you can also see in this boy a striking confirmation of what I

told you earlier — that thoughts do not themselves undergo

change. The thoughts a person produces cannot ever be false. It is

only a question of whether he produces the thoughts at the right

occasion, or again of whether he produces too many thoughts, or too

few. The thoughts themselves are reflections of the external ether.

When

the boy is asked why he keeps his mouth open, and replies: So that

the flies can fly in — that is an exceedingly clever answer;

the thought is, however, wrongly applied. The same thought, applied

later in life to some machine that people were trying to invent,

could turn out to be the grand idea of a clever inventor. Thoughts

are, in themselves, always right and correct; for they are part of

the world ether, they are contained in the thought constitution of

the world ether.

It

is of the greatest importance that the possibility should be there,

for the soul-and-spirit to make proper connection with the world

outside via its own bodily sheaths. In dealing with such a child, we

have to go to work on a twofold principle. We must put before him as

few impressions as possible; and we must try to bring these few

impressions into association with one another. The instruction we set

out to give must be so simplified, must contain so few elements, that

it can quickly be perceived as a connected whole. And it will be, if

we take the trouble to make it so. Whenever we want to get children

to do something — for what I am saying now is true not

for this boy alone; you will be able to prove its truth with the

other children too — whenever we want to get them to do

something, we must take special pains to accompany what the children

have to do with things to stimulate the children's interest and

attention. Where we have children of this kind, who are unable to

come forth out of their body, who fail to bring the soul into the

body and so become master of their own bodily nature, the important

thing will be to provide every possible opportunity for their

interest to develop. Suppose we are beginning to give them

painting. We must, in the first place, be careful to avoid getting at

all anxious or worried if the children make a dreadful mess of their

work! (This warning has been equally necessary in the Waldorf

School.) If we teachers are bent on having everything left perfectly

clean and tidy when the lesson is finished, we shall be following a

false principle. Tidiness is a matter of quite secondary importance.

On the other hand, it is of very great importance that the teacher

should be constantly watching to see that the children are attentive

to each single movement they are making with their hands, to see that

the children follow with close attention all that they are doing.

This requires that the teacher shall be himself fully “there”.

Even more than with other children is it necessary with these, that

the teacher is wide-awake and on the spot the whole time, not

allowing himself ever to lapse into vacancy or vagueness of thought.

“Look!

Take up your brush! And now draw it over the paper!” If we

accompany the whole process with a constant rousing of interest and

attention, we shall achieve something; we shall find that even right

up to the twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth years, a great deal can

be done in this way in the direction of rendering the organism more

supple and pliant. As we go on, we must find it possible to talk to

the child somewhat as follows: “Look! Do you see the tree out

there? I want you to draw that tree. Look at its branches! Can you

show me now on your paper what the tree is like?”

| |

Figure 2

Click image for large view | |

One has, you

see, to be right there the whole time. “Look, there

comes the pony! He's running!” At the same time you point out

the colour of the tree, the pony, etc. “And now there's

Mussolini, the little dog, going to meet him! The little dog is

barking at the pony, and the pony is going like this with his

legs!” You must try to live the whole story with intense

vivacity. And this lively participation in everything that happens,

which is really a manifestation of spirit, is infectious; the

children catch it! You will find that if you want to help children in

this way you need plenty of verve and enthusiasm. If you are dull or

apathetic, if you are the sort of person who prefers to remain seated

and dislikes having to stand up, the sort of person who has not the

smallest inclination to be constantly rousing himself into activity

and movement — then you will never succeed in anything you

undertake in the way of education. For it is not a matter of being

ready with all sorts of cleverly thought-out devices; it is a matter

of doing, on each single occasion, just what that particular occasion

demands.

Another

thing you must do with children of this kind is to engage them in

conversation — as much as ever you can. This boy did not at

first take part in conversation. Now he does. Listen, and you will

see how far he has advanced in this respect. (To the boy) Do you

remember, you told me one day that a pony had arrived? Tell me now,

how big is the pony? Have you ever taken him out? — “Yes,

the pony runs about in the Sonnenhof [The

home for backward children in Arlesheim, Switzerland.] all

the time; and it lies down on the grass.” — Is it in

the stable when it rains? And is there a big pony too? —

“Yes, the big pony is called Markis.” —

You see, if you make conversation with him in this way, he joins in

and talks with you; whereas before, he used to roar and bellow at

you. Another extraordinarily interesting thing to observe is the

following. When he came to us the boy spoke English only. He has

learned comparatively quickly to speak German. You can indeed see in

him a beautiful example of how language pours itself right down into

the ether body and physical body. But the construction of his own

language had become more firmly fixed in him than it is in other

children; we have, in fact, in this boy a wonderful opportunity to

study how the construction of a language sticks fast. He does not say

“Ich bin gewesen” (I have been), but “Ich have

gebeen”. He is finding his way into the German language quite

well, but takes with him into the German the form and configuration

of the English. He has many other similar expressions. Instead of

“Geh weg!” (Go away!), he says “Geh aweg!”

From this very firmness with which the English language has

established itself in him, you can see how stiff and rigid his body

is. If you take pains to get him to talk, doing all you can to draw

him out, you will discover that he has a great deal more to overcome

than most children. For what he has already learned sits terribly

tight in him. By bringing life into him however, constantly

new life, we shall gradually enable the stiffened body to grow

inwardly supple and mobile. If you can, for instance, get him to say

“Ich bin gewesen”, that will be a real achievement on his

part; for it will mean he has roused himself to inner mobility.

Beware however of trying to reach the result by force, by driving it

home, as it were; no, it must be arrived at by conversation, by

engaging the boy again and again, untiringly, in conversation. A

child of this kind should be able to notice that we take an interest

in him, and share in what he is doing. We must ask him questions, for

instance, about things he has had to do with, things with which he

must obviously be familiar, making plain to him in this way that we

ourselves are concerned in what he has experienced. That is for him

very important.

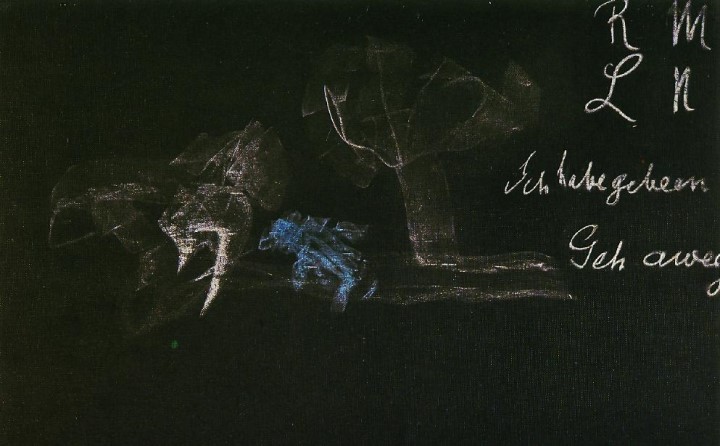

It

will not, I think, be difficult for you to realise how helpful

Curative Eurythmy can be for a boy like this. Suppose he does the

movements for R and L. R is a “turning”; something is

turning round, is revolving. There at once you have mobility. Most of

you are attending the lecture course on Eurythmy, and will know also

what L signifies. Think what formative forces the tongue is

developing when L is spoken! L is the sound that signifies yielding

or compliance, adapting oneself to fall in with something. And that

is what the boy's organism needs: to be made pliant and supple, so

that it shall be ready to adapt itself. And then you will remember

how I said that in him the inbreathing process outweighs the

outbreathing process. We have therefore to see that the outbreathing

is stimulated as much as ever possible, and that the boy himself

participates in it. This happens in M. M is the sound that belongs

particularly to the outbreathing. When it is done in Eurythmy, the

whole limb system comes in to help. And N provides the tendency to

lead back into what belongs to the intellect. We shall accordingly

have for this boy R, M, L, N. As you see, once we have a

comprehensive picture of the child's condition, we know what we have

to do. For this we must, of course, know, first of all, the true

nature of each particular sound, and be absolutely at home in

Eurythmy; then, we must on the other hand have also the ability to

look with clarity and discernment into the bodily organisation of the

child. Both of these are things that can quite well be learned, but

both are completely lacking in the pedagogy of the present day.

In

the case of such a child as we have now before us, I need hardly say

it is even more urgent than with other children that he should be led

to writing by way of painting. We shall therefore begin our teaching

with lessons in painting, working in the way I indicated a little

while ago.

All

that I have described to you will have helped to make it clear that

in this boy the astral body and the I organisation do not penetrate

the physical body and ether body. We must come to their help. And for

this purpose we shall have to intervene also therapeutically. What is

it that needs our support, our backing, as it were? The nervous

system, in so far as it is the foundation for the astral body and I

organisation. How can we strengthen the nervous system? What can we

do?

There

are, as you know, three main ways in which we can work upon the human

being therapeutically: by medicines taken internally, by injections,

and by means of baths or lotions. When you give a person medicine to

take internally, upon what does the medicine work? Fundamentally upon

the metabolic system. You reckon, do you not, on the medicine taking

effect in a simple, straightforward manner on the metabolic system.

If you want to help the rhythmic system, you must give injections.

But if you want to work upon the nervous system, you will have to

give baths or lotions. Now, arsenic has a powerful effect on the

mobility of the astral body, the mobility it requires for diving down

into the physical and ether bodies — and, in fact, also on the

form of the astral body. It can be observed in people who have

undergone arsenic cures that their astral body just slips into the

physical body, glides smoothly into it. When therefore you have a

child in whom you want to produce a right harmony between astral and

ether and physical bodies, arsenic baths will be your obvious remedy.

Prepare a certain quantity of Levico water

[A Spa water containing iron arsenic.] of a particular

percentage and let the child have a bath in it. This will work upon

the nervous system and strengthen the astral body.

And

now there is somewhere else where our help is needed. The forces of

the head system are too feeble in their influence upon the rest of

the body. We must come to the help of the stream of forces which goes

from the head to the lower organism. This stream of forces is

particularly powerful in the earliest years of life, but it is still

maintained between change of teeth and puberty, and even increases in

strength during that period, being at the end of it more powerful

than in the seventh, ninth or eleventh year. We can strengthen this

stream of forces and so help to induce a right correspondence between

metabolic system and nervous system, by making use of a secretion of

hypophysis. [A Weleda preparation

is certainly meant.] For this gives, as it were, a helping

hand to the stream of forces, and exercises from the direction of the

head a harmonising influence upon the metabolic system. We shall

therefore have, side by side, treatment with hypophysis cerebri,

arsenic baths and Curative Eurythmy. With these three working

together, we shall make progress with a boy of this kind.

And

now finally I want to ask your special attention again to what I said

of the need to be always alive and alert, the need to be right

there in whatever we are doing. Particularly in the education and

teaching of backward children, the importance of the need cannot be

over-emphasised. If once we have the inclination and goodwill to try

to attain this, then we shall find that our study and work in the

Anthroposophical Movement will make us more ready to be wide-awake

and alert in all that we undertake. There are, it is true, tendencies

at work among us in an exactly opposite direction. One suffers at

times a kind of pain when one comes into an assemblage of

Anthroposophists. Such a heaviness in the air! No inducing the

members to get a move on! If one begins a discussion, no one else so

much as opens his mouth; why, their very tongues are heavy —

heavy as lead! And they pull such long faces! Out of the question to

expect them to look happy or to laugh! And yet, do you know what is

the first and most essential qualification for a teacher of these

children? Humour! Yes, real humour, the humour of life. You

may have mastered every possible clever method and device, but you

will not be able to educate these children unless you have the

necessary humour.

There

will have to be a feeling and understanding in the anthroposophical

movement for what “movement”, mobility, really is! I do

not want to enlarge on this subject, but I can assure you that I

never meet with less understanding than when, in answer to a question

as to what is to be done in a certain situation, I reply: “Have

enthusiasm!” Enthusiasm — that is what counts; and

particularly in dealing with children who are abnormal.

This

is what I wanted to say to you today.

| |

Lecture 1,

Blackboard Image 1

Click image for large view | |