|

“For the study of thinking, two things coincide which

elsewhere must always appear apart, viz. concept and percept.

If we fail to see this, we shall look upon the concepts which

we have elaborated in response to percepts as mere shadowy

copies of these percepts and we shall take the percepts as

presenting to us reality as it really is. We shall, further,

build up for ourselves a metaphysical world after the pattern

of the perceived world. We shall, each of us according to his

habitual thought-pictures, call this a world of atoms or of

will or of unconscious spirit, etc. And we shall fail to notice

that all the time we have done nothing but erect hypothetically

a metaphysical world modelled upon our perceived world. But if

we clearly apprehend what thinking consists in, we shall

recognise that percepts present to us only a portion of reality

and that the complementary portion (which alone imparts to

reality its full character as real), is experienced by us in

the permeation of percepts by thinking. We shall regard that

which enters into consciousness as thinking, not as some

shadowy copy of reality, but as a self-sustaining spiritual

essence. We shall be able to say of it that it is revealed to

us in consciousness through intuition. Intuition is the purely

spiritual conscious experience of a purely spiritual content.

It is only through intuition that we can grasp the essence of

thinking.

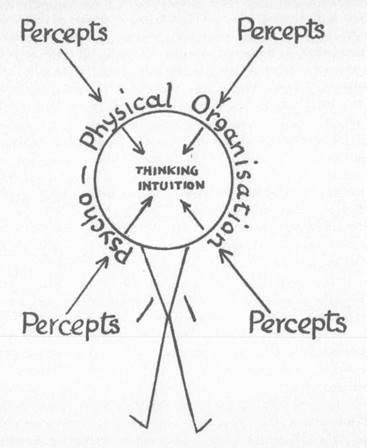

“Only if one wins through, by means of unprejudiced

observation, to the recognition of this truth of the intuitive

essence of thinking, will one succeed in clearing the way for a

conception of the psycho-physical organisation of man. One

recognises that this organisation can produce no effect

whatever on the essential nature of thinking. At first sight,

this seems to be contradicted by obvious facts. For ordinary

experience, human thinking occurs only in connection with and

by means of such an organisation. This dependence upon the

psycho-physical organisation is so patent that we can recognise

its true bearing only if we clearly appreciate that in the

essential nature of thinking it plays no part whatever. Once we

grasp this, we can no longer fail to notice how peculiar is the

relation of the human organisation to thinking. This

organisation contributes nothing to the essential nature of

thought but recedes whenever the thinking-activity appears. It

then suspends its own activity and yields ground. And the

ground thus set free is occupied by thinking. Thus, the essence

which is active in thinking has a two-fold function —

first, it restricts the human organisation in its own activity;

secondly, it steps into the place of it. Yes, even the former,

the restriction of the physical organisation, is an effect of

the activity of thinking and more particularly of that part of

the activity which prepares the manifestation of thinking. This

explains the sense in which thinking has its counterpart in the

organisation of the body. Once we perceive this, we can no

longer misapprehend what significance for thinking this

physical counterpart has. When we walk over soft ground, our

feet leave impressions in the soil. We do not believe that the

forces of the ground, from below, have formed these

foot-prints. We do not attribute to such forces any share in

the production of the foot-prints. Correspondingly, if without

prejudice we observe the essential nature of thinking, we shall

not attribute any share in it to the traces in the physical

organism which thinking produces in preparing its manifestation

through the body.”

We

are called upon here, very urgently indeed, for

“unprejudiced observation” of thinking. We must not

take it for granted — because the tendencies of this

particular phase of history run so tumultuously in that

direction — that thinking can be explained only as the

final product of physical-physiological processes. This hostile

prejudice may be latent in the student who feels himself

antipathetic to Dr. Steiner's line of thought. But the reader

who is sympathetic with Dr. Steiner's line of thought is likely

to be in a more unhopeful situation still. The danger is that

he will agree with what Dr. Steiner says, not because he has

observed it in himself, but because Dr. Steiner says it. ... We

are called upon to make, each of us, our own independent

observation of our own thinking. Unless we are able to be

completely objective, we render ourselves incapable of

listening to the argument, of effectively grasping it.

“But if we clearly apprehend what Thinking consists in,

we shall see that Percepts present to us only a portion of

reality and that the complementary portion — which alone

gives complete reality — is experienced by us in the

permeation of Percepts by Thinking.”

What do these words mean? Have we taken in what has been argued

in Part I of this book? Can we state to ourselves by what right

Dr. Steiner is able to make such an assertion?

As

apprehended by our senses, the world is mere appearance; it has

no true existence; it consists of meaningless particulars; it

is unintelligible. But as soon as we grasp it with our

thinking, we find it taking on meanings, values,

intelligibility, reality. This forces us to ask ourselves

— “If Thinking can effect such a transformation,

what sort of a thing is it?” We observe that Thinking,

like a king, confers relationships, establishes laws, groups

particulars into wholes, mediates the world-order. We note that

Thinking is not in any way derived from nor dependent upon

Percepts; we see that it completely transcends the perceptible;

we see that only in and through Thinking have Percepts come to

life. We realise that we are in the presence of a

“self-existing spiritual essence.”

“Thinking is revealed to us through intuition;”

“Only through intuition can we grasp the essence of

Thinking” ... All other items of experience are as if

“shot at us out of a gun;” they are felt as

externals. Thinking however we experience from within. What am

I to make of this plainly observable fact? I can give myself no

explanation of it except to say that whereas all other things

are in existence of themselves, my Thinking arises only

through and in me. The world of Percepts consists of

things that are not-me, of things un-me-ised;

Thinking is ME. America is there already in existence; so is

the sky; so is this table; so is my next door neighbour; but

not Thinking. If Thinking is to be in existence, I must bring

it into existence. “I think, therefore I am” really

signifies that Thinking is indissolubly one with my very

being.

Man

truly enough is part of nature. He is subject to natural

causation. His psycho-physical organisation mediates to him

external perceptual forces. Impelled by these, he is nothing

better than an animal, a plant, or a stone. “Our

dependence on the psychophysical organisation is obvious ...

but in the essential nature of Thinking it plays no part

whatever. It recedes whenever Thinking-activity appears; it

suspends its own activity; it yields ground. And the ground

thus set free is occupied by Thinking.”

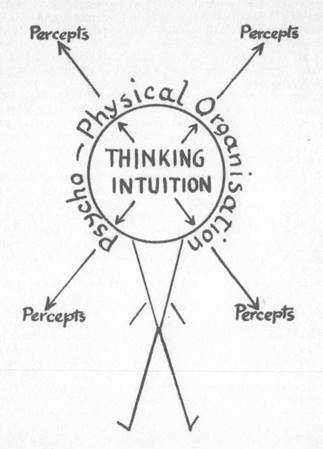

We

are actors in a cosmic drama. When we think, we clear the stage

of perceptual rubbish so that this drama can go on. Thinking is

the power to create within ourselves a free space whereinto

physical forces are refused entry. As long as I am only a

sleeping, perceptualising creature, I am subject to natural

causation; when I awaken, when I become my Thinking Self, I

then become myself a cause.

To

me personally, observing myself, it seems beyond controversy

that by means of thinking, I can and do bring into existence

within myself a self-existing essence, wherein and wherefrom I

am no longer motivated by the external, the unknown, the

perceptual. … To prolong further the argument upon this

point would be unprofitable. The reader must forgive me if I

assume that the fact is established.

Within me is a source of spiritual activity. Whenever I choose,

I can ignore it; I can treat it as non-existent; I can let my

actions originate — through my psycho-physical

organisation — in the external-perceptual. I can let

myself be motivated openly or obscurely by the forces operative

in nature or in social conditions. I can allow the determinants

of my conduct to be such things as sex, fear, anger, the power

of the State, social convention, moral platitudes, obsolete

ideas, conscience. In so far as I let this kind of thing happen

to me, I am unfree: —

Alternatively, I can say “No” to the forces that

assail me from the external-perceptual and “Yes,”

to the intuitions that arise within me. I can refuse to let

myself be made into the plaything of obscure forces external to

my selfhood. I can, instead, in imaginativeness and in love, in

crystal-clear consciousness, creatively, give myself the

motives for what I do. This is to be “free.”

|