Anthroposophy Today, Number 2,

Winter 1986

Intervals of the Life on Earth

RUDOLF STEINER

A lecture

given at Dornach, 30 May 1915. From a shorthand report unrevised by

the lecturer, published by permission of the Rudolf Steiner Nachlassverwaltung.

English translation by David MacGregor.

If you put together what I told you yesterday

with the other lectures (Dornach 23, 24, 29 May 1915) which I gave here, a

week ago, you will obtain an important key, as it were, to many things in

Spiritual Science. I will now give you only the chief ideas needed for the

further course of our considerations, in order to enable you to find your

bearings. About a week ago I pointed out the significance of the processes

which are called, from the aspect of the physical world, destructive

processes I pointed out that, from the aspect of the physical world,

reality is attributed generally only to what arises and forms itself, as it

were, out of nothing and attains a perceptible existence. Thus people speak

of reality when they see the plant shoot up from the root and develop from

leaf to leaf toward the blossom, and so on. But they do not speak of

reality in the same sense when they look upon the gradual withering and

dying, upon the last streaming out, one might say, towards

nothingness.

But for one who wishes to understand the

world, it is necessary in the strictest sense of the word to look also at

so-called destruction, at processes of dissolution, at what finally arises,

as far as the physical world is concerned, as a streaming-out toward

nothingness.

For in the physical world consciousness can never arise where sprouting,

germinating processes alone take place; consciousness begins only where

what has sprouted in the physical world is in its turn eliminated,

destroyed. I have shown that those processes which life brings forth in us

must be destroyed by the soul-spiritual if consciousness is to arise in the

physical world. Indeed, the truth of the matter is that when we perceive

something external, our soul-spiritual has to bring about destructive

processes in our nervous system, and these destructive processes mediate

consciousness. Whenever we become conscious of something, these processes

of consciousness must come from destructive processes. And I have shown

that the most important process of destruction for the life of the human

being, the process of death, creates the consciousness which we possess

during the time after death. Through the fact that our soul-spiritual

experiences the complete dissolving and separation of the physical and

etheric bodies, the merging of the physical and etheric bodies with the

general physical and the general etheric world, through this, and out of

the process of death, our soul-spiritual creates the power to be able to

have processes of perception between death and a new birth. The saying of

Jacob Böhme “Thus death is the root of all life”

[Jacob Böhme: Six

Theosophical Points (1620).]

takes on thereby a higher significance for the whole interrelation of world

phenomena. No doubt the following question has often arisen before your

souls: ‘What happens during the time through which the

human soul passes between death and a new birth?’ It has

often been pointed out that this period of time is a long one for the

normal human life, compared to the time which we pass here in the physical

body between birth and death. The period of time between death and a new

birth is short only in the case of human beings who have applied their life

in a manner inimical to the world, and have done only what may be called,

in a true sense of the word, criminal. In this case there is a short lapse

of time between death and a new birth. But, in the case of people who have

not given themselves up to egoism alone, but who have spent their life

between birth and death in a normal way, the period passed between death

and a new birth is usually relatively long.

But the following question should burn, as it were, in our souls:

‘By what is the return of a human soul to a new physical

incarnation regulated?’ The reply to this question is

connected intimately with everything which can be learned with regard to

the significance of the destructive processes which I have mentioned.

Picture to yourselves that when we enter physical existence we are born

with our souls into quite specific conditions. We are born into a

particular age and impelled towards particular people. So we are born into

quite specific conditions. You should consider deeply that our life between

birth and death is, in reality, filled with everything into which we are

born. What we think, what we feel, in short the whole content of our life,

depends on the time into which we are born.

Now you will

readily understand that what thus surrounds us when we are born into

physical existence is dependent on preceding causes, on what took place

previously. Suppose that we are born at a certain moment and go through

life between birth and death. But if you also take into consideration what

surrounds you, this does not stand there by itself but is the result of

what went before. I would say, you are brought together with what went

before, with people. These people are children of other people, who are in

turn children of still others, and so on. If we consider only these

physical conditions of the succession of the generations, you will say:

‘When I enter physical existence, and during my education, I

receive much from the people who surround me.’ But these, in

their turn, have received a great deal from their ancestors, and from

their ancestors' friends and relations, and so on. Human beings must

go further and further back in order to find the causes of what they

really are.

If we then allow

our thoughts to continue, we may say that we are also able to pursue a

certain current which goes beyond our birth. This current hp brought with

it, as it were, everything that constitutes our environment during the life

between birth and death; and if we pursue it still further back, we come to

a point where our preceding incarnation can be found. Thus, when retracing

the time before our birth, we would have a long period during which we

dwelt in the spiritual world. Many things happened on Earth during this

time. But these things brought about the conditions in which we live, into

which we are born. And then at last we come in the spiritual world to the

time when we were on the Earth in an earlier incarnation. When we speak of

these conditions we mean of course average conditions. Exceptions are

naturally very numerous, but they all lie in the direction which I indicated

before for types who come more quickly to earthly incarnation.

On what does it

depend that, after a time has passed, we are born again just here? If we

look back to our former incarnations, we were surrounded during our time on

Earth by conditions; these conditions had their effects. We were surrounded

by people; these people had children and passed on to the children their

feelings and ideas. The children in turn did the same with their own

descendants, and so on. But if you study historical life you will say that

there comes a time in historical evolution when we are no longer able to

trace in the descendants anything identical with or even similar to the

ancestors. Everything is passed on; yet the fundamental character which is

there in a particular time appears diminished in the children and yet more

so in the grandchildren and so on until a time comes when nothing more can

be found of the fundamental character of the environment in which one lived

during the preceding incarnation. Thus the stream of time works at the

destruction of what was once the fundamental character of the

environment.

We observe this

destruction in the time between death and a new birth; and, when the

character of the earlier period has been extinguished, when nothing more of

it is there, when the things which, as it were, mattered to us in previous

incarnations have been destroyed, the moment comes when we re-enter earthly

existence. Just as, in the second half of our life, our life is a kind of

erosion of our physical existence, so there must occur, between death and a

new birth, a wearing-away of earthly conditions, an annihilation, a

destruction. And new conditions, a new surrounding must be there, into

which we are born.

So we are born

anew when everything for the sake of which we were born before has been

destroyed and annihilated. Consequently this idea of the destructive

process is connected with the successive return of our incarnation on

Earth. And what creates our consciousness at the moment of death, when we

see the body fall away from our soul-spiritual, is intensified in this

moment of death, at this beholding of destruction; this beholding of the

process of annihilation must take place in earthly conditions between our

death and a new birth.

Now you will

understand that someone who takes no interest at all in what surrounds him

on Earth, who is really not interested in anyone or any being but only in

what suits him and who simply lives for the moment, is not strongly

connected with the conditions and things on the Earth. He also

has no interest in following their gradual erosion, but returns very soon

in order to make amends, in order now really to live with the conditions

with which he must live in order to learn to understand their gradual

destruction. Someone who has not lived with earthly conditions does not

understand their destruction and disintegration. Those people, however, who

have lived quite intensely and in the fundamental character of any one

period have the tendency above all, if nothing interferes with this, to

bring about the destruction of what they were born into and to appear again

when something quite new has emerged. Of course, there are exceptions in an

upward direction, and it is important for us to consider these in

particular. Let us suppose that we become familiar with a movement such as

the present spiritual-scientific movement, at this time when it is not in

harmony with what surrounds it, when it is completely alien to its

environment. The spiritual-scientific movement is in this case not

something which we are born into, but something which we have to work at,

of which we will that it should enter the spiritual development of earthly

culture. Above all, it is a question of living with conditions which are in

opposition to Spiritual Science and of appearing again when the Earth is

changed to such an extent that spiritual-scientific conditions can really

take hold of the life of culture.

Here we have an

exception trending upward. There are exceptions in an upward and in a

downward direction. Certainly the most earnest co-workers of Spiritual

Science prepare themselves to appear in earthly existence again as soon as

possible, in that they work at the same time to the end that the conditions

into which they are born disappear. If you can grasp this last thought, you

will realise that, to a certain extent, you help the spiritual beings to

guide the world by devoting yourselves to what lies in their intentions.

When we look upon our present time, we must say that on the one hand we

have eminently what goes into decadence and downfall. Those who have a

heart and a soul for Spiritual Science were placed into this period in

order to see how it is ripe for downfall. Here on Earth you are made

acquainted with things which one can get to know only on Earth. But you

bear that up into the spiritual world, you behold the downfall of the epoch

and you will return again when that calls forth a new epoch, which lies in

the innermost impulses of spiritual-scientific striving. Thus to a certain

extent the plans of the spiritual leaders and guides of earthly

evolution are furthered through what people take up into themselves who

concern themselves with something which is not, so to speak, the culture of

our time.

Perhaps you will be acquainted with the

reproaches which are levelled at the adherents of Spiritual Science by

people of the present time; that they concern themselves with something

which often appears outwardly unfruitful, which does not intervene in the

conditions of our time. It is really necessary that people in

Earth-existence busy, themselves with something which has a significance

for subsequent evolution, but not directly for our time. When objections

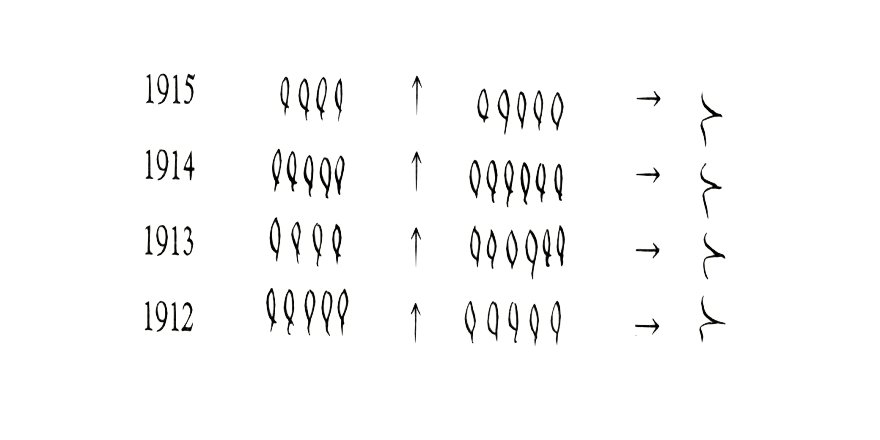

are raised, the following should be born in mind. Imagine that these are

the successive years, 1915, 1914, 1913, 1912, and that these are the cereal

grains (centre) of the successive years. What I draw here (right) are the

mouths which consume the grains.

Now someone

could come along and say that the only important thing is the arrow which

goes from the grain into the mouths (→), for that is

what supports the people of the successive years. He might say that whoever

thinks realistically would look only at these arrows, which go from the

grains to the mouths. But the grains of cereal care little for that, for

this arrow. They do not bother about that at all. Rather they have only the

tendency to develop each grain on into the next year. The grains of cereal

are interested only in this arrow (↑), they do not

concern themselves with the fact that they will also be eaten; that does

not bother them at all. That is a side effect, something that arises by the

by. Each grain of cereal, if I may put it like this, has the will, the

impulse, to pass over into the next year, in order to become there a grain

of cereal once more. It is a good thing for the mouths that the grains

follow the direction of these arrows (↑); for if all the

grains were to follow the direction of these arrows (→),

then the mouths here in the next year would have nothing left to eat. If the

grains of 1913 had all followed this arrow (→), then the

mouths of the year 1914 would have had nothing left to eat.

If someone

wanted to apply materialistic thinking consistently, he would examine the

grains to see how they are composed chemically so that they yield the best

possible nutritional products. But such a study would not be worthwhile,

for this tendency does not lie in the grains of cereal; rather they have

the tendency to care for their further development and to develop over into

the grain of the following year.

It is similar

also with the development of the world. Those people truly follow the

course of the world who care for it that evolution proceeds, while those

who become materialists follow the mouths that only look at this arrow

(→). But those who care for it that the course of the

world continues need not be led astray in this striving of theirs to

prepare the immediately following times, just as little as the cereal

grains let themselves be distracted from preparing those of the next year,

even though the mouths demand the arrows which point in a quite different

direction.

Towards the end

of my book

Riddles of Philosophy

I referred to

this thinking and pointed out that what is generally called materialistic

cognition can be compared with the consumption of the cereal grains and

that what really takes place in the world can be compared with what happens

through propagation from one grain of cereal to that of the following year.

Consequently what one calls scientific cognition is of just as little

significance for the inner nature of things as eating is for the continuing

growth of the grains of cereal. And today's science,

which concerns itself only with the way in which one gets into the human

mind what one can know from the things, does exactly the same as the man

who utilises the grains of cereal for food; for what the grains are when

they are eaten has nothing at all to do with their inner nature. Just as

little does external cognition have anything to do with what develops

within things.

In this way I

have tried to toss a thought into the philosophical hustle and bustle and

it will be interesting to see whether it will be understood or whether even

such a very plausible thought will be met again and again with the foolish

rejoinder: ‘Yes, but Kant has already proved that cognition cannot

reach things.’ However, he proved it only for a cognition which can

be compared with the consumption of the grains and not for a

cognition which arises with the progressive development which is in things.

But we have to realise that we must repeat in all possible forms to our age

and to the age which is coming — but not rashly,

fanatically or by agitation — what the principles and

essence of Spiritual Science are, until it has sunk in. It is just the

characteristic trait of our time, that Ahriman has made skulls very hard

and dense and that they may be softened again only slowly. So no one, I

would say, must draw back in fear and trembling from the necessity to

emphasise in all possible forms what is the being and the impulse of

Spiritual Science.