|

LECTURE VII

Dornach, May 27th, 1922

I

spoke yesterday about how man's etheric and astral bodies

develop. Today I want to indicate how during different

epochs man attained knowledge of this kind. A description

of how higher knowledge is attained provides insight into man's

being from various aspects and also into his relation to

the world. It is by no means necessary that everyone should be

able to repeat these practices, but a description of how higher

knowledge was arrived at in the past and how it is arrived at

now will throw light on matters of vital importance for

every individual.

The

paths by which in very remote times men acquired supersensible

knowledge were very different from those appropriate

today. I have often drawn attention to the fact that in ancient

times man possessed a faculty of instinctive

clairvoyance. This clairvoyance went through many

different phases to become what may be described as modern

man's consciousness of the world, a consciousness out of which

a higher one can be developed. In my books Occult

Science — an Outline and Knowledge of the Higher

Worlds and its Attainment and other writings is

described how man at present, when he understands his own

times, can attain higher knowledge. Today I want to describe

these things from a certain aspect with reference to what was

said yesterday.

When we look back to the spiritual strivings of man in a very

distant past we find among others the one practiced in the

Orient within the culture known later as the Ancient Indian

civilization. Many people nowadays are returning to what was

practiced then because they cannot rouse themselves to

the realization that, in order to penetrate into supersensible

worlds, every epoch must follow its own appropriate

path.

On

previous occasions I have mentioned that, from the masses of

human beings who lived during the period described in my

Occult Sciences as the Ancient Indian epoch, certain

individuals developed, in a manner suited to that age, inner

forces which led them upwards into supersensible worlds. One of

the methods followed is known as the path of Yoga; I have

spoken about this path on other occasions.

The

path of Yoga can best be understood if we first consider

the people in general from among whom the Yogi

emerged — that is to say, the one who sets out to attain

higher knowledge by this path. In those remote ages of

mankind's evolution, human consciousness in general was very

different from what it is today. In the present age we

look out into the world and through our senses perceive colors,

sounds and so on. We seek for laws of nature prevailing in the

physical world and we are conscious that if we attempt to

experience a spirit-soul content in the external world then we

add something to it in our imagination. It was different in the

remote past for then, as we know, man saw more in the external

world than ordinary man sees today. In lightning and

thunder, in every star, in the beings of the different

kingdoms of nature, the men of those times beheld spirit and

soul. They perceived spiritual beings, even if of a lower kind,

in all solid matter, in everything fluid or aeriform. Today's

intellectual outlook declares that these men of old, through

their fantasy, dreamed all kinds of spiritual and psychical

qualities into the world around them. This is known as

animism.

We

little understand the nature of man, especially that of man in

ancient times, if we believe that the spiritual beings

manifesting in lightning and thunder, in springs and rivers, in

wind and weather, were dream-creations woven into nature by

fantasy. This was by no means the case. Just as we perceive red

or blue and hear C sharp or G, so those men of old beheld

realities of spirit and soul in external objects. For them it

was as natural to see spirit-soul entities as it is for us to

see colors and so on. However, there was another aspect to this

way of experiencing the world; namely, that man in those days

had no clear consciousness of self.

The

clear self-consciousness which permeates the normal human

being today did not yet exist. Though he did not express it,

man did not, as it were, distinguish himself from the external

world. He felt as my hand would feel were it conscious: that it

is not independent, but an integral part of the organism. Men

felt themselves to be members of the whole universe. They had

no definite consciousness of their own being as separate from

the surrounding world. Suppose a man of that time was walking

along a river bank. If someone today walks along a river

bank downstream he, as modern, clever man, feels his legs

stepping out in that direction and this has nothing whatever to

do with the river. In general, the man of old did not

feel like that. When he walked along a river downstream, as was

natural for him to do, he was conscious of the spiritual beings

connected with the water of the river flowing in that

direction. Just as a swimmer today feels himself carried

along by the water — that is, by something

material — so the man of old felt himself guided downstream

by something spiritual. That is only an example chosen at

random. In all his experiences of the external world man felt

himself to be supported and impelled by Gods of wind, river,

and all surrounding nature. He felt the elements of nature

within himself. Today this feeling of being at one with

nature is lost. In its place man has acquired a strong feeling

of his independence, of his individual `I'.

The

Yogi rose above the level of the masses whose experiences

were as described. He carried out certain exercises of which I

shall speak. These exercises were good and suitable for

the nature of humanity in ancient times; they have later fallen

into decadence and have mainly been used for harmful ends. I

have often referred to these Yoga breathing exercises.

Therefore, what I am now describing was a method for the

attainment of higher worlds that was suitable and right only

for man in a very ancient oriental civilization.

In

ordinary life breathing functions unconsciously. We breathe in,

hold the breath and exhale; this becomes a conscious

process only if in some way we are not in good health. In

ordinary life breathing remains for the most part in

unconscious process. But during certain periods of his

exercises the Yogi transformed his breathing into a

conscious inner experience. This he did by timing the inhaling,

holding and exhaling of the breath differently and so

altered the whole rhythm of the normal breathing. In this way

the breathing process became conscious. The Yogi projected

himself, as it were, into his breathing. He felt himself one

with the indrawn breath, with the spreading of the breath

through the body and with the exhaled breath. In this way he

was drawn with his whole soul into the breath.

In

order to understand what is achieved by this let us look at

what happens when we breathe: When we inhale, the breath is

driven into the organism, up through the spinal cord, into the

brain; from there it spreads out into the system of nerves and

senses. Therefore, when we think, we by no means depend only on

our senses and nervous system as instruments of thinking. The

breathing process pulsates and beats through them with its

perpetual rhythm. We never think without this whole process

taking place, of which we are normally unaware because the

breathing remains unconscious.

The

Yogi, by altering the rhythm of the breath, drew it consciously

into the process of nerves and senses. Because the altered

breathing caused the air to billow and whirl through the brain

and nerve-sense-system the result was an inner experience of

their function when combined with the air. As a consequence, he

also experienced a soul element in his thinking within the

rhythm of breathing.

Something extraordinary happened to the Yogi by this means. The

process of thinking, which he had hardly felt as a function of

the head at all, streamed into his whole organism. He did not

merely think but felt the thought as a little live creature

that ran through the whole process of breathing which he had

artificially induced.

Thus, the Yogi did not feel thinking to be merely a

shadowy, logical process, he rather felt how thinking

followed the breath. When he inhaled he felt he was taking

something from the external world into himself which he

then let flow with the breath into his thinking. With his

thoughts he took hold, as it were, of that which he had inhaled

with the air and spread through his whole organism. The result

of this was that there arose in the Yogi an enhanced feeling of

his own T, an intensified feeling of self. He felt his

thinking pervading his whole being. This made him aware

of his thinking particularly in the rhythmic air-current within

him.

This had a very definite effect upon the Yogi. When man today

is aware of himself within the physical world he quite rightly

does not pay attention to his thinking as such. His senses

inform him about the external world and when he looks back upon

himself he perceives at least a portion of his own being. This

gives him a picture of how man is placed within the world

between birth and death. The Yogi radiated the ensouled

thoughts into the breath. This soul-filled thinking pulsated

through his inner being with the result that there arose in him

an enhanced feeling of selfhood. But in this experience, he did

not feel himself living between birth and death in the physical

world surrounded by nature. He felt carried back in memory to

the time before he descended to the earth; that is, to the time

when he was a spiritual-soul being in a spiritual-soul

world.

In

normal consciousness today, man can reawaken experiences

of the past. He may, for instance, have a vivid

recollection of some event that took place ten years ago

in a wood perhaps; he distinctly remembers all the details, the

whole mood and setting. In just the same way did the Yogi,

through his changed breathing, feel himself drawn back into the

wood and atmosphere, into the whole setting of a spiritual-soul

world in which he had been as a spiritual-soul being. There he

felt quite differently about the world than he felt in his

normal consciousness. The result of the changed relationship of

the now awakened selfhood to the whole universe, gave

rise to the wonderful poems of which the Bhagavad Gita is a

beautiful example.

In

the Bhagavad Gita we read wonderful descriptions of how the

human soul, immersed in the phenomena of nature, partakes of

every secret, steeping itself in the mysteries of the world.

These descriptions are all reproductions of memories,

called up by means of Yoga breathing, of the soul — when

it was as yet only soul — and lived within a spiritual

universe. In order to read the ancient writings such as the

Bhagavad Gita with understanding one must be conscious of what

speaks through them. The soul, with enhanced feeling of

selfhood, is transported into its past in the spiritual world

and is relating what Krishna and other ancient initiates had

experienced there through their heightened

self-consciousness.

Thus, it can be said that those sages of old rose to a higher

level of consciousness than that of the masses of people. The

initiates strictly isolated the “self' from the external

world. This came about, not for any egoistical reason, but as a

result of the changed process of breathing in which the soul,

as it were, dove down into the rhythm of the inner air

current. By this method a path into the spiritual world

was sought in ancient times.

Later this path underwent modifications. In very ancient times

the Yogi felt how in the transformed breathing his thoughts

were submerged in the currents of breath, running through them

like little snakes. He felt himself to be part of a weaving

cosmic life and this feeling expressed itself in certain

words and sayings. It was noticeable that one spoke

differently when these experiences were revealed through

speech. What I have described was gradually felt less

intensely within the breath; it no longer remained within

the breathing process itself. Rather were the words breathed

out and formed of themselves rhythmic speech. Thus, the changed

breathing led, through the words carried by the breath, to the

creation of mantras; whereas, formerly, the process and

experience of breathing was the most essential, now these

poetic sayings assumed primary importance. They passed over

into tradition, into the historical consciousness of man

and subsequently gave birth later to rhythm, meter, and so on,

in poetry.

The

basic laws of speech which are to be seen, for instance,

in the pentameter

[

Pentameter:

in prosody, a line scanning in five feet.

]

and hexameter

[

Hexameter:

Greek measure of six — in poetry, line scanning in six feet.

]

as used in ancient Greece,

point back to what had once long before been an

experience of the breathing process. An experience which

transported man from the world in which he was living

between birth and death into a world of spirit and

soul.

This is not the path modern man should seek into the spiritual

world. He must rise into higher worlds, not by the detour of

the breath, but along the more inward path of thinking itself.

The right path for man today is to transform, in meditation and

concentration, the otherwise merely logical connection between

thoughts into something of a musical nature. Meditation today

is to begin always with an experience in thought, an

experience of the transition from one thought into another,

from one mental picture into another.

While the Yogi in Ancient India passed from one kind of

breathing into another, man today must attempt to project

himself into a living experience of, for example, the color

red. Thus, he remains within the realm of thought. He must then

do the same with blue and experience the rhythm: red- blue;

blue-red; red-blue and so on, which is a thought- rhythm. But

it is not a rhythm which can be found in a logical thought

sequence; it is a thinking that is much more alive.

If

one perseveres for a sufficiently long time with

exercises of this kind — the Yogi, too, was obliged

to carry out his exercises for a very long time — and

really experiences the inner qualitative change, and the swing

and rhythm of: red- blue; blue-red; light-dark;

dark-light — in short, if indications such as those

given in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds are

followed, the exact opposite is achieved to that of the Yogi in

ancient times. He blended thinking with breathing, thus

turning the two processes into one. The aim today is to

dissolve the last connection between the two, which, in any

case, is unconscious. The process by which, in ordinary

consciousness, we think, and form concepts of our natural

environment is not only connected with nerves and senses: a

stream of breath is always flowing through this process. While

we think, the breath continually pulsates through the nerves

and senses.

All

modern exercises in meditation aim at entirely separating

thinking from breathing. Thinking is not on this account

torn out of rhythm, because as thinking becomes separated from

the inner rhythm of breath it is gradually linked to an

external rhythm. By setting thinking free from the breath we

let it stream, as it were, into the rhythm of the external

world. The Yogi turned back into his own rhythm. Today man must

return to the rhythm of the external world. In Knowledge of

the Higher Worlds you will find that one of the first

exercises shows how to contemplate the germination and

growth of a plant. This meditation works toward separating

thinking from the breath and to let it dive down into the

growth forces of the plant itself.

Thinking must pass over into the rhythm pervading the external

world. The moment thinking really becomes free of the bodily

functions, the moment it has torn itself away from breathing

and gradually united with the external rhythm, it dives

down — not into the physical qualities of things — but

into the spiritual within individual objects.

We

look at a plant: it is green and its blossoms are red. This our

eyes tell us, and our intellect confirms the fact. This is the

reaction of ordinary consciousness. We develop a

different consciousness when we separate thinking from

breathing and connect it with what exists outside. This

thinking yearns to vibrate with the plant as it grows and

unfolds its blossoms. This thinking follows how in a

rose, for example, green passes over into red. Thinking

vibrates within the spiritual which lies at the foundation of

each single object in the external world.

This is how modern meditation differs from the Yoga

exercises practiced in very ancient times. There are

naturally many intermediate stages; I chose these two extremes.

The Yogi sank down, as it were, into his own breathing process;

he sank into his own self. This caused him to experience this

self as if in memory; he remembered what he had been before he

came down to earth. We, on the other hand, pass out of the

physical body with our soul and unite ourselves with what lives

spiritually in the rhythms of the external world. In this way

we behold directly what we were before we descended to the

earth. This is the consequence of gradually entering into the

external rhythm.

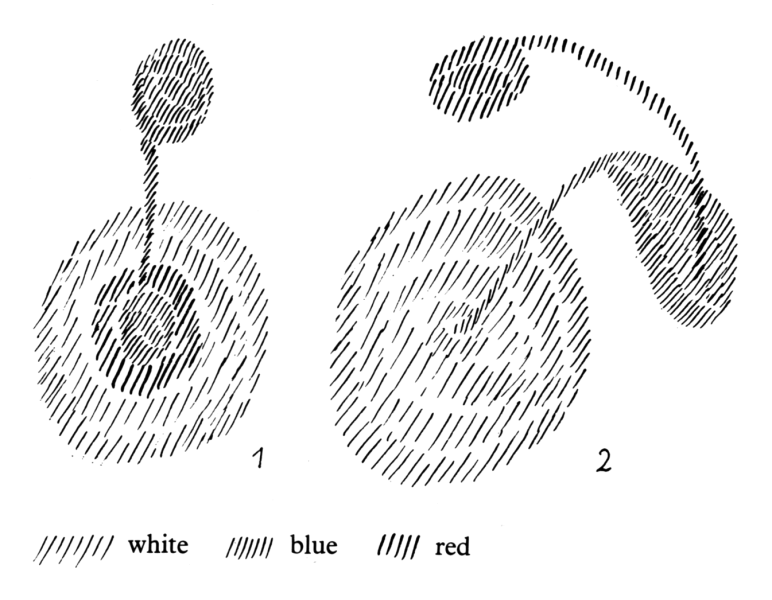

To

illustrate the difference, I will draw it schematically: Let

this be the Yogi (first drawing, white lines). He

developed a strong feeling of his `I' (red). This enabled

him to remember what he was, within a soul-spiritual

environment, before he descended to earth (blue). He went

back on the stream of memory.

Let

this be the modern man who has attained supersensible

knowledge (second drawing, white lines). He develops a process

that enables him to go out of his body (blue) and live within

the rhythm of the external world and behold directly, as

an external object (red), what he was before he descended to

earth.

| |

Diagram 1

Click image for large view | |

Thus, knowledge of one's existence before birth was in ancient

times in the nature of memory, whereas at the present time a

rightly developed cognition of pre-birth existence is a direct

beholding of what one was (red). That is the difference.

That was one of the methods by which the Yogi attained insight

into the spiritual world. Another was by adopting certain

positions of the body. One exercise was to hold the arms

outstretched for a long time; or he took up a certain position

by crossing his legs and sitting on them and so on. What was

attained by this?

He attained the possibility to perceive what can be

perceived with those senses which today are not even

recognized as senses. We know that man has not just five senses

but twelve. I have often spoken about this — for example,

apart from the usual five he has a sense of balance through

which he perceives the equilibrium of his body so that he does

not fall to the right or left, or backwards or forwards. Just

as we perceive colors, so we must perceive our own

balance or we should slip and fall in all directions.

Someone who is intoxicated or feels faint loses his balance

just because he fails to perceive his equilibrium. In order to

make himself conscious of this sense of balance, the Yogi

adopted certain bodily postures. This developed in him a

strong, subtle sense of direction. We speak of above and below,

of right and left, of back and front as if they were all the

same. The Yogi became intensely conscious of their

differences by keeping his body for lengthy periods in

certain postures. In this way he developed a subtle awareness

of the other senses of which I have spoken. When these are

experienced they are found to have a much more spiritual

character than the five familiar senses. Through them the Yogi

attained perception of the directions of space.

This faculty must be regained but along a different path. For

reasons which I will explain more fully on another

occasion the old Yoga exercises are unsuitable today.

However, we can attain an experience of the qualitative

differences within the directions of space by undertaking such

exercises in thinking as I have described. They separate

thinking from breathing and bring it into the rhythm of the

external world. We then experience, for instance, what it

signifies that the spine of animals lies in the horizontal

direction whereas in man it is vertical. It is well known that

the magnetic needle always points north-south. Therefore, on

earth the north-south direction means something special, for

the manifestation of magnetic forces, since the magnetic

needle, which is otherwise neutral, reacts to it. Thus, the

north-south direction has a special quality. By penetrating

into the external rhythm with our thoughts we learn to

recognize what it means when the spine is horizontal or

vertical. We remain in the realm of thought and learn

through thinking itself. The Indian Yogi learned it, too, but

by crossing his legs and sitting on them and by keeping his

arms raised for a long time. Thus, he learned from the bodily

postures the significance of the invisible directions of space.

Space is not haphazard but organized in such a way that the

various directions have different values.

| |

Diagram 2

Click image for large view | |

The exercises that have been described which lead man into

higher worlds are mainly exercises in the realm of thought.

There are exercises of an opposite kind; among

them are the various methods employed in asceticism. One such

method is the suppression of the normal function of the

physical body through inflicting pain and all kinds of

deprivations. It is practically impossible for modern man to

form an adequate idea of the extremes to which such

exercises were carried by ascetics in former times.

Modern man prefers to be as firmly as possible within his

physical body. But whenever the ascetic suppressed some

function of the body by means of physical pain, his spirit-soul

nature drew out of his organism.

In

normal life the soul and spirit of man are connected with the

physical organism between birth and death in accordance

with the human organization as a whole. When the bodily

functions are suppressed, through ascetic practices, something

occurs which is similar to when today someone sustains an

injury. When one knows how modern man generally reacts to

some slight hurt then it is clear that there is a great

difference between that and what the ascetic endured just to

make his soul organism free. The ascetic experienced the

spiritual world with the soul organism that had been driven out

through such practices. Nearly all of the earlier great

religious revelations originated in this way.

Those concerned with modern religious life make light of these

things. They declare the great religious revelations to be

poetic fiction, maintaining that whatever insight man acquires

should not cause pain. The seekers of religious truths in

former times did not take this view. They were quite clear

about the fact that when man is completely bound up with his

organism, as of necessity he must be for his earthly

tasks — the gain was not to portray unworldliness as an

ideal — then he cannot have spiritual experiences. The

ascetics in former times sought spiritual experiences by

suppressing bodily life and even inflicting pain.

Whenever pain drove out spirit and soul from a bodily member

that part which was driven out experienced the spiritual world.

The great religions have not been attained without pain but

rather through great suffering.

These fruits of human strivings are today accepted through

faith. Faith and knowledge are neatly separated. Knowledge of

the external world, in the form of natural science, is acquired

through the head. As the head has a thick skull, this causes no

pain, especially as this knowledge consists of extremely

abstract concepts. On the other hand, those concepts handed

down as venerable traditions are accepted simply through

faith. It must be said though, that basically, knowledge and

faith have in common the fact that today one is willing to

accept only knowledge that can be acquired painlessly,

and faith does not hurt any more than science, though its

knowledge was originally attained through great pain and

suffering.

Despite all that has been said, the way of the ascetic

cannot be the way for present-day man. On some other

occasion we will consider the reason. In our time it is

perfectly possible, through inner self-discipline and training

of the will, to take in hand one's development which is

otherwise left to education and the experiences of life. One's

personality can be strengthened by training the will. One

can, for example, say to oneself: Within five years I shall

acquire a new habit and during that time I shall concentrate my

whole will power upon achieving it. When the will is trained in

this way, for the sake of inner perfection, then one loosens,

without ascetic practices, the soul-spiritual from the bodily

nature. The first discovery, when such training of the will is

undertaken for the sake of self-improvement, is that a

continuous effort is needed. Every day something must be

achieved inwardly. Often it is only a slight

accomplishment, but it must be pursued with iron

determination and unwavering will. It is often the case

that if, for example, such an exercise as concentration each

morning upon a certain thought is recommended, people will

embark upon it with burning enthusiasm. But it does not last,

the will slackens and the exercise becomes mechanical because

the strong energy which is increasingly required is not

forthcoming. The first resistance to be overcome is one's

own lethargy; then comes the other resistance, which is of an

objective nature, and it is as if one had to fight one's

way through a dense thicket. After that, one reaches the

experience that hurts because thinking, which has

gradually become strong and alive, has found its way into the

rhythm of the external world and begins to perceive the

direction of space — in fact, perceive what is alive. One

discovers that higher knowledge is attainable only through

pain.

I

can well picture people today who want to embark upon the path

leading to higher worlds. They make a start and the first

delicate spiritual cognition appears. This causes pain, so they

say they are ill; when something causes pain one must be ill.

However, the attainment of higher knowledge will often be

accompanied by great pain, yet one is not ill. No doubt it is

more comfortable to seek a cure than continue the path.

Attempts must be made to overcome this pain of the soul

which becomes ever greater as one advances. While it is easier

to have something prescribed than continue the exercises, no

higher knowledge is attained that way. Provided the body is

robust and fit for dealing with external life, as is normally

the case at the present time, this immersion in pain and

suffering becomes purely an inner soul path in which the

body does not participate. When man allows knowledge to

approach him in this way, then the pain he endures signifies

that he is attaining those regions of spiritual life out of

which the great religions were born. The great religious truths

which fill our soul with awe, conveying as they do those lofty

regions in which, for example, our immortality is rooted,

cannot be reached without painful inner experiences.

Once attained, these truths can be passed on to the

general consciousness of mankind. Nowadays they are

opposed simply because people sense that they are not as easy

to attain as they would like. I spoke yesterday about how

the changed astral body unites, within the heart, with the

ether body. I also explained how all our actions, even those we

cause others to carry out, are inscribed there. Just think how

oppressive such a thought would be to many people. The great

truths do indeed demand an inner courage of soul which enables

it to say to itself: If you could experience these things you

must be prepared to attain knowledge of them through

deprivation and suffering. I am not saying this to discourage

anyone, but because it is the truth. It may be discouraging for

many, but what good would it do to tell people that they can

enter higher worlds in perfect comfort when it is not the case.

The attainment of higher worlds demands the overcoming of

suffering.

I

have tried today, my dear friends, to describe to you how it is

possible to advance to man's true being. The human soul and

spirit lie deeply hidden within him and must be attained. Even

if someone does not set out himself on that conquest he must

know about what lies hidden within him. He must know about such

things as those described yesterday and how they run

their course. This knowledge is a demand of our age. These

things can be discovered only along such paths as those I

have indicated again today by describing how they were trodden

in former times and how they must be trodden now.

Tomorrow we shall link together the considerations of yesterday

and those of today and in so doing penetrate further into

the spiritual world.

|