|

Thus he gropes his way out of Manichaeism, precisely out of

that part of it which must be called its most significant part,

at least in this connection. Augustine gropes after something

spiritual which is free of all sensuousness. And in this he

finds himself exactly in that era of human soul-development in

which the soul had to free itself from the contemplation of

matter as something spiritual and of the spiritual as something

material. We entirely misunderstand Greek philosophy in

reference to this. And because I tried for once to describe

Greek philosophy as it really was, the beginning of my

“Riddles of Philosophy”

seems so difficult

to understand. When the Greeks speak of ideas, of conceptions,

when Plato speaks of them, people now believe that Plato or the

Greeks mean the same by ideas as we do. This is not so, for the

Greeks spoke of ideas as something which they observed in the

outer world like colours or sounds. That part of Manichaeism

which we find slightly changed, with — let us say —

an oriental tinge, that is already present in the whole Greek

view of life. The Greek sees his idea just as he sees colours.

And he still possesses that material-spiritual,

spiritual-material life of the soul, which does not rise to

what we know as spiritual life. Whatever we may call it, a mere

abstraction or the true content of our soul, we need not decide

at the present moment; the Greek does not yet reckon with what

we call a life of the soul free from matter; he does not

distinguish, as we do, between thinking and outward use of the

senses. The whole Platonic philosophy ought to be seen in this

light to be fully understood.

We

can now say, that Manichaeism is nothing but a post-Christian

variation (with an oriental tinge) of something already

existing among the Greeks. Neither do we understand that

wonderful genius who closes the circle of Greek philosophy,

Aristotle, unless we know that whenever he speaks of concepts,

he still keeps within the meaning of an experienced tradition

which regarded concepts as belonging to the outer world of the

senses as well as perceptions, though he is already getting

close to the border of understanding abstract thought free from

all evidence of the senses. Through the point of view to which

men's souls had attained during his era, through actual events

happening within the souls of men in whose rank Augustine was a

distinctive, prominent personality, Augustine was forced not

just only to experience within his soul, as the Greeks had

done, but he was forced to rise to thoughts free from

sense-perceptions, to thoughts which still kept their meaning

even if they were not dealing with earth, air and sea, with

stars, sun and moon; thoughts which had a content beyond the

sense of vision.

And

now only philosophers and philosophies spoke to him which spoke

of what they had to say from an entirely different point of

view, that is, from the super-spiritual one just explained.

Small wonder, then, that these souls striving in a vague way

for something not yet in existence and trying with their minds

to seize what was there, could only find something they could

not absorb; small wonder that these souls sought refuge in

scepticism. On the other hand, the feeling of standing on a

sound basis of truth and the desire to get an answer to the

question of the origin of Evil was so strong in Augustine, that

equally powerful in his soul lived that philosophy which stands

under the name of Neoplatonism at the end of Greek philosophic

development. This is focused in Plotinus and reveals to us

historically what neither the Dialogues of Plato and still less

Aristotelian philosophy can reveal, namely, the course of the

whole life of the soul when it looks for a greater

intensiveness and a reaching beyond the normal. Plotinus is

like a last straggler of a type which followed quite different

paths to knowledge, to the inner life of the soul, from those

which were gradually understood later. Plotinus must appear

fantastic to present-day men. To those who have absorbed

something of mediaeval scholasticism Plotinus must appear as a

terrible fanatic, indeed, as a dangerous one.

I

have noticed this repeatedly. My old friend Vincenz Knauer, the

Benedictine monk, who wrote a history of philosophy and who has

also written a book about the chief problems of philosophy from

Thales to Hamerling was, I may well say, good-nature incarnate.

This man never let himself go except when he had to deal with

Neoplatonism, in particular with Plotinus, and he would then

get quite angry and would denounce Plotinus terribly as a

dangerous fanatic. And Brentano, that intelligent Aristotelian

and Empiric, Franz Brentano, who also carried mediaeval

philosophy deeply and intensely in his soul, wrote a little

book: Philosophies that Create a Stir, and there he

fumes about Plotinus in the same way, for Plotinus the

dangerous fanatic is the philosopher, the man who in his

opinion “created a stir” at the close of the

ancient Greek period. To understand him is really

extraordinarily difficult for the modern philosopher.

Concerning this philosopher of the third century we have next

to say this: What we experience as the content of our

understanding, of our reason, what we know as the sum of our

concepts about the world is entirely different for him. I might

say, if I may express myself clearly: we understand the world

through sense-observations which through abstraction we bring

to concepts, and end there. We have the concepts as inner

psychic experience and if we are average men of to-day we are

more or less conscious that we have abstractions, something we

have sucked as it were out of things. The important thing is

that we end there; we pay attention to the experiences of the

senses and stop at the point where we make the total of our

concepts, of our ideas. It was not so for Plotinus. For him

this whole world of sense-experience scarcely existed. But that

which meant something to him, of which he spoke as we speak of

plants and minerals and animals and physical men, was something

which he saw lying above concepts; it was a spiritual world and

this spiritual world had for him a nether boundary, namely, the

concepts. While we get our concepts by going to concrete

things, make them into abstractions and concepts and say:

concepts are the putting-together, the extractions of ideal

nature from the observation of the senses, Plotinus said

— and he paid little heed to the observation of the

senses: “We, as men, live in a spiritual world, and what

this spiritual world reveals to us finally, what we see as its

nether boundary, are concepts.” For us the world of the

senses lies below concepts: for Plotinus there is

above concepts a spiritual world, the intellectual

world, the world really of the kingdom of the spirit. I might

use the following image: let us suppose we were submerged in

the sea, and looking upward to the surface of the water, we saw

nothing but this surface, nothing above the surface, then this

surface would be the upper boundary. Suppose we lived in the

sea, we might perhaps have in our soul the feeling: This

boundary would be the limit of our life-element, in which we

are, if we were organized as sea-beings. But for Plotinus it

was not so. He took no notice of the sea round him; but the

boundary which he saw, the boundary of the concept-world in

which his soul lived, was for him the nether boundary of

something above it; just as if we were to take the

boundary of the water as the boundary of the atmosphere and the

clouds and so on. At the same time this sphere above concepts

is for Plotinus what Plato calls the “world of

ideas” and Plotinus throughout imagines that he is

continuing the true genuine philosophy of Plato. This

“idea-world” is, first of all, completely a world

of which one speaks in the sense of Plotinism. Surely it would

not occur to you, even if you were Subjectivists or followers

of the modern Subjectivist philosophy, when you look out upon

the meadow, to say: I have my meadow, you have yours, and so

and so has his meadow; even if you are convinced that you each

have only before you the image of a meadow, you speak of the

meadow in the singular, of one meadow which is out there. In

the same way Plotinus speaks of the one idea-world, not of the

idea-world of this mind, or of another or of a third

mind. In this idea-world — and this we see already

in the whole manner in which one has to characterize the

thought-process leading to this idea-world — in this

idea-world the soul has a part. So we may say: The soul, the

Psyche, unfolds itself out of the idea-world and experiences

it. And the Soul, just as the idea-world creates the Psyche, in

its turn creates the matter in which it is embodied. So that

the lower material from which the Psyche takes its body is

chiefly a creation of this Psyche.

But

precisely there is the origin of individuation, there the

Psyche, which otherwise takes part in the single idea-world,

becomes a part of body A, and body B, and so on, and through

this fact there appear, for the first time, individual souls.

It is just as if I had a great quantity of liquid in one mass,

and having taken twenty glasses had filled each with the

liquid, so that I have this liquid, which as such is a unity,

thus divided, just so I have the Psyche in the same condition,

because it is incorporated in bodies which, however, it has

itself created. Thus in the Plotinistic sense a man can view

himself according to his exterior, his vessel. But that is at

bottom only the way in which the soul reveals itself, in which

the soul also becomes individualized. Afterward man has to

experience within him his very own soul, which raises itself

upward to the idea-world. Still later there comes a higher form

of experience. That one should speak of abstract concepts

— that has no meaning for a Plotinist; for such abstract

concepts — well, a Plotinist would have said: “What

do you mean — abstract concepts? Concepts surely cannot

be abstract: they cannot hang in the air, they must be

suspended from the spirit; they must be the concrete

revelations of the spiritual.”

The

interpretation therefore that ideas are any kind of

abstractions, is therefore wrong. This is the expression of an

intellectual world, a world of spirituality. It is also what

existed in the ordinary experience of those men out of whose

relationships Plotinus and his fellows grew. For them such talk

about concepts, in the way we talk about them, had absolutely

no meaning, because for them there was only a penetration of

the spiritual world into souls. And this concept-world is found

at the limit of this penetration, in experiencing. Only when we

went deeper, when we developed the soul further, only then

there resulted something which the ordinary man could not know,

which the man experienced who had attained a higher stage. He

then experienced that which was above the idea-world —

the One, if you like to call it so — the experience of

the One. This was for Plotinus the thing that was

unattainable to concepts, just because it was above the world

of concepts, and could only be attained if one could sink

oneself into oneself without concept, a state we describe here

in our spiritual science as Imagination. You can read about it

in my book,

Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and How to Attain It.

But there is this difference: I have treated the

subject from the modern point of view, whereas Plotinus treated

it from the old. What I there call the Imagination is just that

which, according to Plotinus stands above the

idea-world.

From this general view of the world Plotinus really also

derived all his knowledge of the human soul. It is, after all,

practically contained in it. And one can be an individualist in

the sense of Plotinus if one is at the same time a human being

who recognizes how man raises his life upwards to something

which is above all individuality, to something spiritual;

whereas in our age we have more the habit of reaching downwards

to the things of the senses. But all this which is the

expression of something which a thorough scientist regards as

fanaticism, all this is in the case of Plotinus, not something

thought out, these are no hypotheses of his. This perception

— right up to the One which only in exceptional cases

could be attained — this perception was as clear to

Plotinus and as obvious, as is for us to-day the perception of

minerals, plants and animals. He spoke only in the sense of

something which really was directly experienced by the soul

when he spoke of the soul, of the Logos, which was part of the

Nous, of the idea-world and of the One. For Plotinus the whole

world was, as it were, a spirituality — again a different

shade of philosophy from the Manichaean and from the one

Augustine pursued. Manichaeism recognizes a sense-supersense;

for it the words and concepts of matter and spirit have as yet

no meaning. Augustine strives to reach a spiritual experience

of the soul that is free from the sense and to escape from his

material view of life. For Plotinus the whole world is

spiritual, things of the senses do not exist. For what appears

material is only the lowest method of revealing the spiritual.

All is spirit, and if we only go deep enough into things,

everything is revealed as spirit.

This is something which Augustine could not accept. Why?

Because he had not the necessary point of view. Because he

lived in his age as a predecessor — for if I might call

Plotinus a “follower” of the ancient times in which

one held such philosophic views, — though he went on into

the third century, — Augustine was a predecessor of those

people who could no longer feel and perceive that there was a

spiritual world underneath the idea-world. He just did

not see that any more. He could only learn it by being told. He

might hear that people said it was so, and he might develop a

feeling that there was something in it which was a human road

to truth. That was the dilemma in which Augustine stood in

relation to Plotinism. But he was never completely diverted

from searching for an inner understanding of this Plotinism.

However, this philosophical point of view did not open itself

to him. He only guessed: in this world there must be something.

But he could not fight his way to it.

This was the mood of his soul when he withdrew himself into a

lonely life, in which he got to know the Bible and

Christianity, and later the sermons of Ambrosius and the

Epistles of St. Paul; and this was the mood of his soul which

finally brought him to say: “The nature of the world

which Plotinus sought at first in the nature of the idea-world

of the Nous, or in the One, which one can attain only in

specially favourable conditions of soul, why! That has appeared

in the body on earth, in human form, through

Christ-Jesus.” That leapt at him as a conviction out of

the Bible: “Thou hast no need to struggle upward to the

One, thou needest but look upon that which the historical

tradition of Christ-Jesus interprets. There is the One come

down from heaven, and is become man.” And Augustine

exchanges the philosophy of Plotinus for the Church. He

expresses this exchange clearly enough. For instance, when he

says, “Who could be so blind as to say: 'The Apostolic

Church merits no Faith” the church which is so faithful

and supported by so many brotherly agreements that it has

transmitted their writings as conscientiously to those that

come after, as it has kept their episcopal sees in direct

succession down to the present Bishops. This it is on which

Augustine, out of the soul-mood described, laid the chief

stress: — that, if one only goes into it, it can be shown

in the course of centuries that there were once men who knew

the Lord's disciples, and here is a continuous tradition of a

sort worthy of belief, that there appeared on earth the very

thing which Plotinus knew how to attain in the way I have

indicated.

And

now there arose in Augustine the effort, in so far as he could

get to the heart of it, to make use of this Plotinism to

comprehend that which had through Christianity been opened to

his feeling and his inner perception. He actually applied the

knowledge he had through Plotinism to understand Christianity

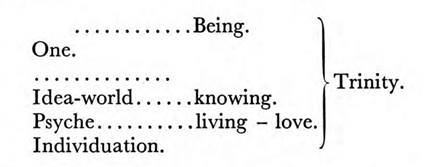

and its meaning. Thus, for example, he transposed the concept

of the One. For Plotinus the One was something experienced; for

Augustine who could not attain this experience, the One became

something which he defined with the abstract term

“being”; the idea-world, he defined with the

abstract concept “knowing,” and Psyche with the

abstract concept “living,” or even

“love.” We have the best evidence that Augustine

proceeded thus in that he sought to comprehend the spiritual

world, with neoplatonic and Plotinistic concepts, that there is

above men a spiritual world, out of which the Christ descends.

The Trinity was something which Plotinism made clear to

Augustine, the three persons of the Trinity, the Father, the

Son, the Holy Ghost.

And

if we were to ask seriously, of what was Augustine's soul full,

when he spoke of the Three Persons — we must answer: It

was full of the knowledge derived from Plotinus. And this

knowledge he carried also into his understanding of the Bible.

We see how it continues to function. For this Trinity awakens

to life again, for example, in Scotus Erigena, who lived at the

court of Charles the Bald in the ninth century, and who wrote a

book on the divisions and classification of Nature in which we

still find a similar Trinity: Christianity interprets its

content from Plotinism.

But

what Augustine preserved from Plotinism in a specially strong

degree was something that was fundamental to it.

You

must remember that man, since the Psyche reaches down into the

material as into a vessel, is really the only earthly

individuality. If we ascend slightly into higher regions, to

the divine or the spiritual, where the Trinity originates, we

have no longer to do with individual man, but with the species,

as it were, with humanity. We no longer direct our

visualization in this bald manner towards the whole of

humanity, as Augustine did as a result of his Plotinism. Our

modern concepts are against it. I might say: Seen from down

there, men appear as individuals; seen from above — if

one may hypothetically say that — all humanity appears as

one unity. From this point of view the whole of humanity became

for Plotinus concentrated in Adam. Adam was all humanity. And

since Adam sprang from the spiritual world he was as a being

bound with the earth, which had free will, because in him there

lived that which was still above, and not that which arises

from error of matter — itself incapable of sin. It was

impossible for this man who was first Adam to sin or not to be

free, and therefore also impossible to die. Then came the

influence of that Satanic being, whom Augustine felt as the

enemy-spirit. It tempted and seduced the man. He fell into the

material, and with him all humanity.

Augustine stands, with what I might call his derived knowledge,

right in the midst of Plotinism. The whole of humanity is for

him one, and it sinned in Adam as a whole, not as an

individual. If we look clearly between the lines particularly

of Augustine's last writings, we see how extraordinarily

difficult it has become for him thus to regard the whole of

mankind, and the possibility that the whole fell into sin. For

in him there is already the modern man, the predecessor as

opposed to the successor; there lived in him the individual man

who felt that individual man grew ever more and more

responsible for what he did, and what he learnt. At certain

moments it appeared to him impossible to feel that individual

man is only a member of the whole of the human race. But

Neo-Platonism and Plotinism were so deep in him that he still

could look only at the whole of humanity. And so this condition

in the whole man, this condition of sin and mortality —

was transferred into that of the impossibility to be free, the

impossibility to be immortal; all humanity had thus fallen, had

been diverted from its origin. And God, were He righteous,

would have simply thrown humanity aside. But He is not only

righteous, He is also merciful — so Augustine felt.

Therefore, he decided to save a part of mankind, note well, a

part. That is to say, God's decision destined a part of mankind

to receive grace, whereby this part is to be led back from the

condition of bondage and mortality to the condition of

potential freedom and immortality, which, it is true, can only

be realized after death. One part is restored to this

condition. The other part of mankind — namely, the

not-chosen — remains in the condition of sin. So mankind

falls into these two divisions, into those that are chosen and

those who are cast out. And if we regard humanity in this

Augustinian sense, it falls simply into these two divisions:

those who are destined for bliss without desert, simply because

it is so ordained in the divine management, and those who,

whatever they do, cannot attain grace, who are predetermined

and predestined to damnation.

This view, which also goes by the name of Predestination,

Augustine reached as a result of the way in which he regarded

the whole of humanity. If it had sinned it deserved the fate of

that part of humanity which was cast out. We shall speak

to-morrow of the terrible spiritual battles which have resulted

from this Predestination, how Pelagianism and semi-Pelagianism

grew out of it. But to-day I would add as a final remark: we

now see how Augustine stands, a vivid fighting personality,

between that view which reaches upward toward the spiritual,

according to which humanity becomes a whole, and the urge in

his soul to rise above human individuality to something

spiritual which is free from material nature, but which, again,

can have its origin only in individuality. This was just the

characteristic feature of the age of which Augustine is the

forerunner, that it was aware of something unknown to men in

the old days — namely individual experience. To-day,

after all, we accept a great deal as formula. But Klopstock was

in earnest and not merely the maker of a phrase when he began

his “Messiah” with the words: “Sing, immortal

soul, of sinful man's salvation.” Homer began, equally

sincerely: “Sing, O Goddess, of the wrath. ... “:

or “Sing, O Muse, to me now of the man, far-travelled

Odysseus.” These people did not speak of something that

exists in individuality, they interpreted something of

universal mankind, a race-soul, a Psyche. It is no empty

phrase, when Homer lets the Muse sing, in place of himself. The

feeling of individuality awakens later, and Augustine is one of

the first of those who really feel the individual entity of

man, with its individual responsibility. Hence, the dilemma in

which he lived. The individual striving after the non-material

spiritual was part of his own experience. There was a personal,

subjective struggle in him. In later times that understanding

of Plotinism, which it was still possible for Augustine to

have, was — I might say — choked up. And after the

Greek philosophers, the last followers of Plato and Plotinus,

were compelled to go into exile in Persia, and after they had

found their successors in the Academy of Jondishapur, this

looking up to the spiritual triumphed in Western Europe —

and only that remained which Aristotle had bequeathed to the

after-world in the form of a filtered Greek philosophy, and

then only in a few fragments. That continued to grow, and came

in a roundabout way, via Arabia, back to Europe. This

had no longer a consciousness of the idea world, and no

Plotinism in it. And so the great question remained: Man must

extract from himself the spiritual; he must produce the

spiritual as an abstraction. When he sees lions and thereupon

conceives the thought “lions” when he sees wolves

and thereupon conceives the thought “wolves,” when

he “sees man and thereupon conceives the thought”

man these concepts are alive only in him, they arise out of his

individuality. The whole question would have had no meaning for

Plotinus; now it begins to have a meaning, and moreover a deep

meaning.

Augustine, by means of the light Plotinism had shed into his

soul, could understand the mystery of Christ-Jesus. Such

Plotinism as was there was choked up. With the closing by the

Emperor Justinian of the School of Philosophy at Athens in 529

the living connection with such views was broken off. Several

people have felt deeply the idea: We are told of a spiritual

world, by tradition, in Script — we experience by our

individuality supernatural concepts, concepts that are removed

from the material How are these concepts related

to “being?” How so the nature of the

world? What we take to be concepts, are these

only something spontaneous in us, or have they something

to do with the outer world? In such forms the questions

appeared; in the most extreme abstractions, but such as were

the deeply earnest concern of men and the mediaeval Church. In

this abstract form, in this inner-heartedness they appeared in

the two personalities of Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas.

Then again, they came to be called the questions between

Realism and Nominalism. “What is our relationship to a

world of which all we know is from conceptions which can come

only from ourselves and our individuality?”

That was the great question which the mediaeval schoolmen put

to themselves.

If

you consider what form Plotinus had taken in Augustine's

predestinationism, you will be able to feel the whole depth of

this scholastic question: only a part of mankind, and that only

through God's judgment, could share in grace, that is, attain

to bliss; the other part was destined to eternal damnation from

the first, in spite of anything it might do. But what man could

gain for himself as the content of his knowledge came from that

concept, that awful concept of Predestination which Augustine

had not been able to transform — that came out of the

idea of human individuality. For Augustine mankind was a whole;

for Thomas each separate man was an individuality.

How

does this great World-process in Predestination as Augustine

saw it hang together with the experience of separate human

individuality? What is the connection between that which

Augustine had really discarded and that which the separate

human individuality can win for itself? For consider: Because

he did not wish to lay stress on human individuality, Augustine

had taken the teaching of Predestination, and, for mankind's

own sake, had extinguished human individuality. Thomas Aquinas

had before him only the individual man, with his thirst for

knowledge. Thomas had to seek human knowledge and its

relationship to the world in the very thing Augustine had

excluded from his study of humanity.

It

is not sufficient, ladies and gentlemen, to put such a question

abstractly and intellectually and rationally; it is necessary

to grasp such a question with the whole heart, with the whole

human personality. Only then shall we be able to assess the

weight with which this question oppressed those men who, in the

thirteenth century, bore the burden of it.

|