Lecture VI

Dutch and Flemish Painting

Meister Bertram,

Hieronymus Bosch,

Dieric Bouts,

Pieter Brueghel,

Petrus Christus,

Gerard David,

Jan Van Eyck,

Master of Flémalle,

Geertgen tot Sint Jans,

Hugo van der Goes,

Quentin Matsys,

Hans Memling, and

Joachim Patinir.

Dornach, 13th December 1916

The pictures we shall show

today are to illustrate the development of Dutch and Flemish painting

towards the end of the 15th century and on into the 16th.

From the inner historical

point of view, this is one of the most important moments in the evolution

of Art. It is, as you know, the period immediately after the dawn of the

fifth post-Atlantean epoch — that epoch which is called upon to

bring forth, out of the depths of human evolution, all that is connected

with the development of the Spiritual Soul. In the Dutch and Flemish

pictures we shall now consider, this comes to expression in a most

characteristic way. We see in every detail how the Spiritual Soul begins

to work. We can see it, my dear friends, if only we bring to these works

of Art an elementary power of understanding — that is to say, if we

have to some extent escaped the unhappy fate of being historians of Art

after the modern fashion.

The most up-to-date of the

modern critics and historians will, no doubt, consider a critic like

Hermann Grimm an altogether inferior intellect. But if we have not the

misfortune to be quite so up-to-date, then, even if we knew nothing

beforehand of the laws and impulses of human evolution as explained by

Spiritual Science, we should still find in this artistic evolution a

wonderful confirmation of all the differences which Spiritual Science

indicates in its descriptions of the Third, Fourth, and fifth

post-Atlantean epochs. It is interesting to see how gradually there

emerges — century after century during these epochs — what

we may regard as the fundamental frame-work of the artistic conceptions

of today. It is interesting to see the several elements of it emerging

in the most manifold quarters in the evolution of mankind.

If we go back to the history

of drawing and painting, we find that the laws of Space, for example, have

only been evolved by gigantic efforts of the human soul. The older

representations in line and color do not really constitute a pictorial Art

in the modern sense. They are more like a kind of narrative or

story-telling on the flat surface. This applies to a by no means very

distant past. (Without entering at length into these historic aspects, I

will only indicate a few general points of view.)

We can see that in those

olden times, the artist had in his mind's eye some story which he wished

to portray — a story such as one might even narrate in words.

He did not try to represent Space as it is; he simply fixed on to the

flat surface what he desired to represent. The various things that he

relates stand side by side on this flat surface. From our point of view,

we could, at most, regard this as a kind of primitive illustration.

Today we should not even allow the art of illustration to proceed in

this way, merely setting down the events of the narrative on a flat

surface.

At the next stage, an

attempt is made to represent the ordering of things in Space, at any rate,

in a most rudimentary way, by introducing the principle of overlapping.

The artist makes use of the visibility, or partial visibility of this

or that figure.

A figure that stands in

the way of another, is in the foreground; the other stands behind it.

By this method of overlapping, the surface is really used to suggest,

at any rate, the dimension of depth.

At a following stage, the

several figures are already made larger or smaller in proportion, taking

into account that that which appears larger is to the front, while all

that which appears smaller is further back. If, however, we return to

the Third Post-Atlantean period, we find that this spatial treatment

to which we are now accustomed, did not exist at all. They either put

things down on the flat surface, as described above, or else they used

the element of Space to express their thought. This, indeed,

continued into the Graeco-Latin period. Contrary to the way in which

things are really seen, we often find figures which are obviously to

the front (nearer to the spectator) smaller in proportion to other figures

which are further away. In olden times they often made use of this kind

of treatment.

We see a King, for example,

enthroned in the background of the picture. His subjects, in the

foreground, are represented as being smaller in proportion. In Space they

are not really smaller, but according to the conception prevailing, they

are smaller in idea. Hence, while they are placed in the

foreground, they are made smaller. This gives you the transition to a

thing you will frequently find in older times — I mean what we may

call "inverse perspective" compared to the perspective we know

today. In this “inverse perspective” we must imagine things

envisaged as they are seen by a particular figure in the picture. Figures

which are in front from our point of view can, indeed, be smaller than

other figures which are farther back, if a figure in the background

is conceived as the observer of the scene. But to this end the man who

is actually looking at the picture must entirely obliterate himself!

He must either imagine himself away, or he must think himself into

the picture, as it were, — into the personality of the figure

conceived as the observer of the scene.

Here, then, we have an

Impersonal perspective. This “impersonal perspective”

was still suited to the stage of the Fourth Post-Atlantean epoch, when

the Spiritual Soul was not yet so consciously born as afterwards. The

man of the fifth Post-Atlantean epoch cannot forget himself; he demands

a presentation arising from his own point of view. Hence it is that the

art of perspective, strictly related to the visual point of the spectator,

only appears with Brunellesco — that is to say, is the main, with

the beginning of the Renaissance.

We may truly say that what

is now called perspective was first introduced into the technique of Art

at that point of time. Moreover, the South, through the impulses I

characterised in one of the earlier lectures, is the inventor of

perspective. For the South is much concerned with the ordering of things

in the inner relationship of Space; concerned, that is to say, with

qualities in extension. Thus the South is predisposed for mastery in the

whole art of composition, and at a later date we see this art of

composition fertilised by the Southern Renaissance — with all that

I have described already as the inherent impulses which then came to the

surface, and reached so high a degree of perfection.

Thus there comes forth

in Art what we may call the gathering together of things in Space, where

the man who looks at the picture is included in the whole conception.

Truly, this corresponds to the age when the Spiritual Soul is born —

when man becomes conscious of himself.

Hence it is in the south

— in all that is connected with the Southern culture, which we

have described before — it is here that the modern principle of

perspective first arises. We see how it evolves quite naturally out

of the Southern culture.

Meanwhile, however, another

principle is at work, is emerging in the North; this principle we see

in its nascent state, as it were, in the very moment of its origin,

when we turn our gaze to the Brothers Van Eyck.

In the two Van Eycks —

Hubert van Eyck to begin with, and later in his brother Jan —

we see emerging, albeit in a different form as yet, what afterwards came

forth as described when dealing with Rembrandt, for example. Something

which emerges out of the Mid-European, Northern element. These things

always find expression in external symptoms — in outwardly real

symbols, if I may so call them. Brunellesco must be conceived as the

inventor of modern perspective. The ancient perspective — that which

underlies the Greek pictures, for example, — does not possess what

is called a “vanishing point.” It has a whole “vanishing

line.” The scene we see seems to converge, not in a vanishing

point, but in a vanishing line. In this is, indeed, expressed the radical

difference between the ancient perspective and the modern, which is

the perspective of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch.

Brunellesco, then, is

the discoverer of modern perspective. It is discovered in the South.

Whereas in the North — this is no mere tradition, but contains

a profound truth — in the North oil-painting is discovered.

Although Hubert van Eyck was not the sole inventor of oil-painting,

nevertheless, it is true that oil-painting was discovered in the age

and out of the whole milieu out of which he created.

Now what does this signify?

What is the underlying reason? For the art of oil-painting was then

carried to the South. Perspective was carried from the South to the North;

oil-painting from the North to the South. What does this signify?

It is deeply rooted in

their fundamental character and mood of soul. In the South men have

a feeling for coming together mutually in the Group. The South has far

more attachment to the Group-soul as such. Hence the people of the South

are fond of describing themselves as members of such and such a Group.

They have little understanding of the individual principle. Such things

should be taken into account, for Nations will never understand each

other if they take no pains to grasp their several characteristics.

When a man has been brought

up in the more Latin spirit — who has received the inner impulse

of the Southern nature — speaks of his devotion to nation or people

— when he calls himself a Patriot in one sense or another, he means

something very different from the Mid-European who speaks of Patriotism.

Mid-Europe really has no talent for this belonging together, this

gathering of men together into a Group. In Mid-Europe there is a faculty

for the Individual principle. The true native character of Middle Europe

is expressed in the recognition of the Individual, and in the age of the

development of the Spiritual Soul this implies, to begin with, the

recognition of the personality, the human individual —

the person.

Now, if we feel essentially

the Group-element, which is, of course, extensive (spread out in space),

we shall naturally live in the element of composition. One who has

this tendency will have a natural understanding for the art of

composition. If, on the other hand, we have a strong feeling for the

individual principle, we shall seek to mould the individual from within

— outward. Instead of seeing the Spirit, as it were, put forth

its feelers to embrace and hold the Group together, we see the Spirit

within each single form; we place the several individual figures side

by side, seeing the Spirit in each single one. We seek to bring to the

surface of the body what is there in the inner being of the soul.

This is not to be achieved

by perspective, but by color that is irradiated, flooded by

light. Thus in the profoundly Germanic brothers, Van Eyck, we have the

real starting point of the modern art of color, which seeks to hold

fast in the color itself, what comes from the individual character of

the soul to the outer surface of the body.

The brothers Van Eyck

and their successors, derive their essential inner quality from this

Northern Mid-European element, while composition, which gradually finds

its way into their works, is borrowed more from France and Burgundy.

It is no mere matter of

chance that this special development in the 15th century took place

at a time when the districts where these artists lived did not possess

a hard-and-fast political structure. Such a structure was only afterwards

imposed upon them from the South — from France and especially from

Spain. In that period we see spread out over the Northern and Southern

Netherlands the more individual City-formations — towns and cities

whose connection as compact States was at most a very loose one. The

people of those regions, and of that time, had no inclination to think

that men ought to be held together in groups by well-defined States,

where the State itself is the important thing — where the precise

extent and frontiers of a particular State are considered a matter of

importance. To the people out of whom the brothers Van Eyck arose, the

particular nation to which they belonged was not the point. Nor did they

think of what is called the “State,” or trouble themselves

about its frontiers. What mattered to them was that human beings full,

thorough-going human beings — should develop, regardless of the

group to which they might belong.

So we see this Art of the

Southern Netherlands, the regions of Flanders. The inner being of man is

conjured forth to the surface of the body in a tender and thoughtful way.

By a mysterious power they flood their pictures with light, introducing

just that element which color can introduce, for the individual

characterisation of the soul.

Then we see the burgher,

the citizen virtues of the Northern Netherlands reaching down into the

Southern aristocratic element. The life of the burghers gives birth

to that Art which places the individual so thoroughly into the world.

It is, in reality, an overcoming of the Group-soul principles in Art.

And yet, as we shall see

in the very first of our pictures today, how wonderfully the mass-effects

are, nevertheless, attained. But with these mass-effects, it is not that

they are conceived as a group from the outset. They arc not deliberately

constructed: the figures distributed in Space so as to belong together

as a Group. On the contrary, these wonderful groupings arise through

the very fact that each individual being has his full importance, and

takes his stand beside the others.

Such are the things that

we shall recognise out of this portion of artistic evolution. In the

brothers Van Eyck we still have comparatively primitive, rudimentary

groupings in Space, but withal a high degree of inwardness, and a strong

adaptation to what is actually seen, regardless of any hard and fast

conventions.

In effect, we have here

the second pole of that entry into the physical reality in the artistic

life, which belongs to the fifth post-Atlantean period. This pole is in

the North, while the other takes its start from the Italian art of the

Renaissance. There we have the element of composition, and all else is to

some extent subservient to this. In the North we have a creating from

within, outwards. Only gradually and by dint of constant striving do they

arrive at a certain power of composition by the placing together of

individuals portrayed with inwardness of soul. Thus the one aspect of the

naturalistic principle in Art, which belongs to the fifth post-Atlantean

epoch, found its essential fountain-head in these regions. These painters

place their subject in the immediate reality which surrounds them. The

Biblical story, for example, when reproduced in Art by men of earlier

times, was taken right away from their immediate surroundings. But this

period in Art places the Biblical narratives into the midst of the

immediate naturalistic reality. Men of the Netherlands stand before us as

the characters of Biblical history.

What formerly shut one

off, as it were, from the outer naturalistic world — the golden

background and all that was expressed in it — ceases to exist.

On the very soil where we ourselves are standing, the Biblical scenes

move before us.

It goes with this, quite

naturally and inevitably, that they everywhere surround their human

figures with that peculiar treatment of space which we find in their

interiors, not in their outer landscapes. I would express it thus. Having

ceased to be living in the composition, the space itself must be

transposed, transplanted into the picture. Space, as such, must now appear

in the picture. How, then, can this be done? By shaping a portion of the

picture itself as a “space,” that is to say, by placing the

figures in an “interior” — in a room, or the like. Or,

again, by painting a naturalistic space such as forms itself around the

human being in the landscape. Thus with all the impulses of the new age

which, as above described, permeate especially this Dutch and Flemish Art,

we see arising quite naturally, the art of landscape painting. The

landscape appears, often with a mighty and overpowering grandeur, in the

background of the figures, or in some other way.

This Art evolves and

flourishes most beautifully in the age of the free cities, when every town

or city in these regions has a pride in its independence, and feels no

inner need for territorial union with other cities. A certain

international consciousness arises. This freedom from separations, this

freedom from the Group-spirit, is a product of the sound and strong

Germanic burgher-spirit of those times and places.

All this grows out of the

life of the Northern and Southern Netherlands. Influenced very slightly

by the South — influenced only by the Southern art of composition

through the adjoining southern countries — their artistic creation

springs from this democratic strength and soundness of the burghers,

and blossoms forth until the time when the whole thing is eclipsed,

if I may put it so, by the Group-mind once more.

Thus the period in artistic

evolution which we shall illustrate today is at the same time a period

of free development of human beings. I might continue to say many other

things; but I wanted, above all, to fix your minds on the world-historic

moment when this development in Art took place.

We will now proceed at once

to show a number of pictures on the screen.

We begin with the famous

Altar-piece of Ghent, by the Brothers Van Eyck.

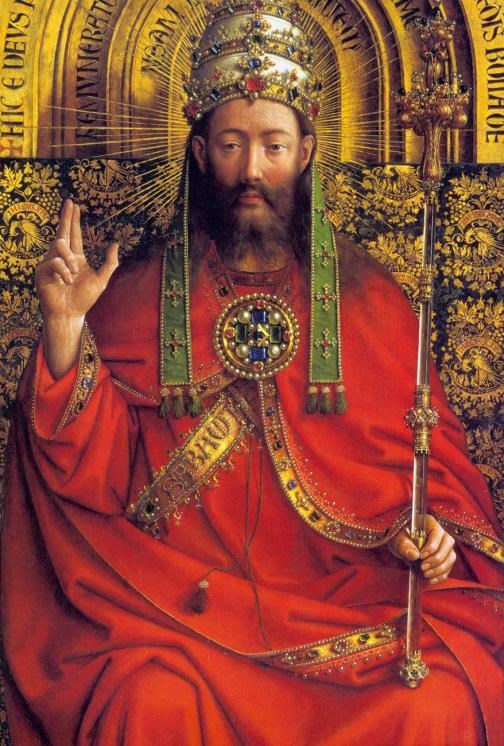

1. The Brothers Van Eyck. Altar-piece. (St. Bavo. Ghent.)

2. God, the Father

3. Mary

4. John

This Altar-piece consists

of many parts. This is the portion seen when the front is opened —

the middle portion above the Altar. The figure in the center, in Papal

costume, is representing God the Father. Conceived in the spirit of the

Church, God the Father is actually represented as a Pope. Nevertheless,

the features I have indicated are recognisable in the whole artistic

composition. If we went back still further, we should find the preceding

evolution altogether steeped in Christian ideas — the Christian

traditions — that is to say, which the ecclesiastics forcibly

impressed upon the people. These traditions most certainly corresponded

to a manner of thought inspired by the Group-consciousness. But out

of the midst of this very element we now witness the individual spirit

making itself felt.

The figure to your left

is Mary; that on the right is St. John. Here, then, we find ourselves

in the first third of the 15th century. Hubert Van Eyck died in 1426;

the Altar-piece was finished by his brother Jan. It is the first third

of the 15th century.

From the same Altar-piece

we will show the angel-pictures, to the right and left of these central

figures.

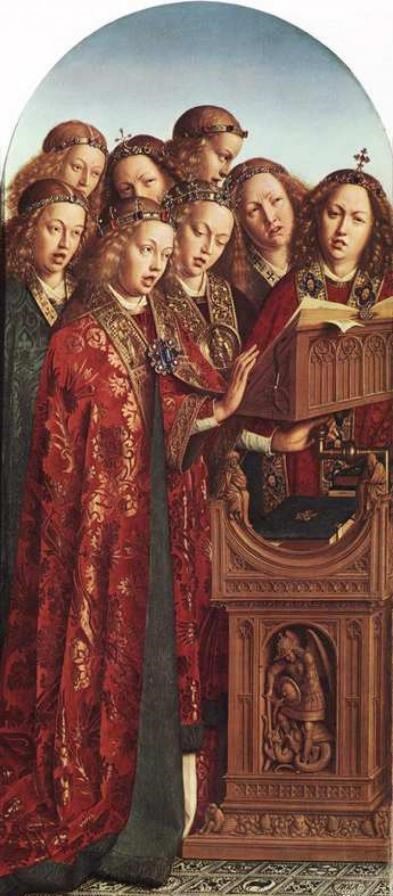

5. Angels making Music

Here you see a group of

angels playing on instruments of music. Compare them with the angels

by the German Christian Masters of the period immediately preceding

this. Lochner, for instance, or the Master of Cologne — the pictures

we saw in a former lecture. You will see how great a difference there is.

The angels here are full-grown human beings, in spite of their clerical

and ceremonial garments — fully developed human beings —

no longer as before, half child-like forms. In such a group as this, you

will see that the artist has not yet reached a thorough-going perspective.

The perspective is only carried through to a slight extent. You see the

whole picture on the surface — spread out like a tapestry. We will

now show the angel-picture from the other side of the altar-piece.

6. Angels singing

This whole Altar-piece

was done by order of a wealthy Burgher for the Church of St. Bavo. The

several parts are now scattered abroad — at Ghent, in Brussels,

in Berlin ...

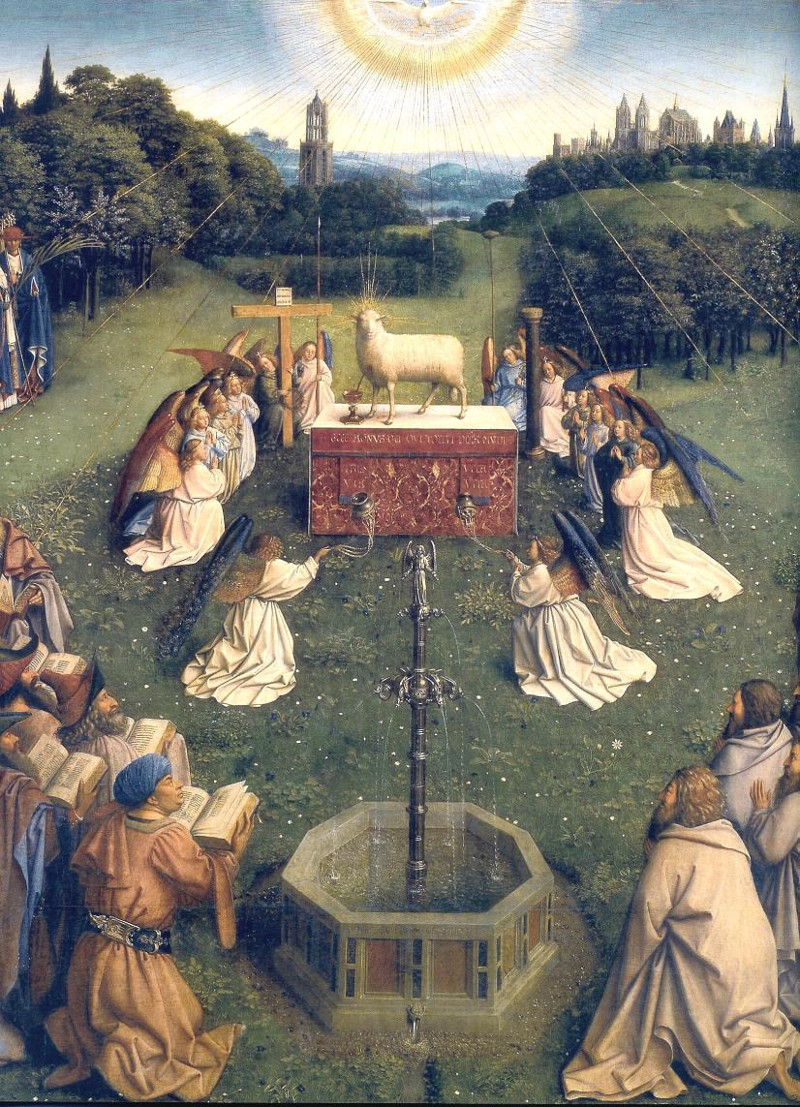

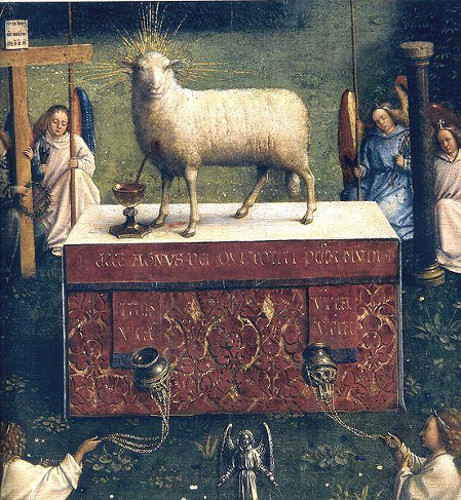

7. The Brothers van Eyck. Adoration of the Lamb.

Here we come to the main

portion of the picture, beneath the other three. The “Adoration

of the Lamb” is one of the fundamental motifs of this and the

preceding period. Here we see it beautifully presented as the fundamental

religious conception which had evolved during the course of many

centuries. It could not have been embodied in this beautiful artistic

form till they had so grown together with this conception as to represent

it thus. Throughout the centuries of Christianity this idea had gradually

taken shape — this idea of the Salvation, the Redemption of mankind

through a great Sacrifice.

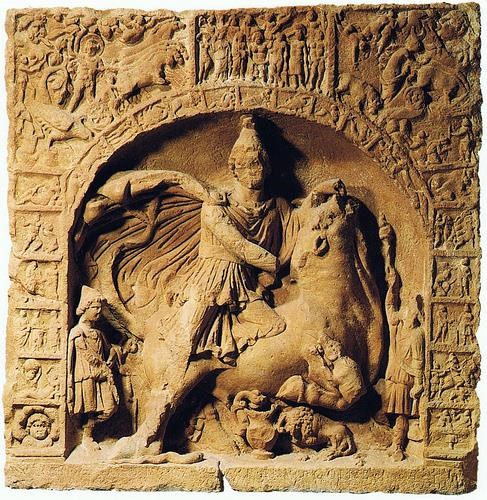

We must go far, far back

in time to realise its full significance. Compare the subject —

the story which this picture tells — with a picture, for example,

of the Mithras Offering. There you have Mithras seated on the Bull;

the Bull is wounded, the blood is flowing. It is the uplifting of Mithras,

His salvation by the overcoming of the Beast. You are familiar with

the deeper spiritual meaning of this picture; it is, if I may so describe

it, the very antithesis of the one we now see before us. The rearing

and rebellious Bull has to be fought down — gives up his blood

by force; the Lamb gives His Blood of His own free will.

8. Adoration of the Lamb as compared to a Mithras-Relief

What does this signify?

Salvation is lifted out of the element in which it was previously

conceived — the element of violence, and strife and conflict. It

comes into the element of free devotion and out-pouring Grace. Such is

the idea which is here expressed. Not by man seeking in pride to rise

beyond himself, seeking to kill his lower nature, but by experiencing

in his soul that which streams through the world and patiently suffers

with the world, will he attain his liberation at every point of this

world's existence, his redemption.

Such is the Universal —

and therefore, the individually universal — principle of redemption

which we here find expressed. The Lamb is One, yet no one being is striking

it. Therefore we see it offered up for every one of those who worship

it, who draw near to it from all their different spheres of life —

near to the Lamb of Salvation, near to the Fountain of Life.

The greatest conception

of the Middle Ages, grown and matured in the course of the centuries,

is thus recorded at the end of the Mediaeval Ages by the brothers Van

Eyck, and there arises in this period one of the greatest of all works

of Art.

Of course, we must bear

in mind the points of view I emphasised just now. The individual principle,

creating from out of the inner life, wrestles still with an inadequate

mastery of the treatment of space. You will, for instance, scarcely

be able to imagine a spectator situated with his eye in such a place

as to perceive the spatial distribution of this figure here (at the

bottom of the picture).

Very beautifully Van Eyck

portrayed how the Impulse of the Lamb works in the various callings,

in the several branches of human life. Here are some examples.

9. Brothers van Eyck. The Knights and Judges. (From

the Altar-piece at Ghent. Berlin Museum.)

These are the Judges and

the Knights as they draw near to the Lamb. All these are portions of

the same great Altar-piece. The next is a very tender picture:

10. Brothers van Eyck. The Pilgrims and Hermits. (From

the Altar-piece at Ghent.)

Here we can already admire

the treatment of landscape in relation to the human beings to whom it

belongs.

Hubert van Eyck died in

1426, when the Altar-piece was not nearly finished. His brother Jan

continued working at it for many years, and scholars have long been

engaged in the dispute, which they seem to regard as so important, as

to which portions are due to Hubert and which to Jan. This dispute is,

after all, more or less superfluous, if we are interested in the artistic

aspect. We now come to another picture by Van Eyck.

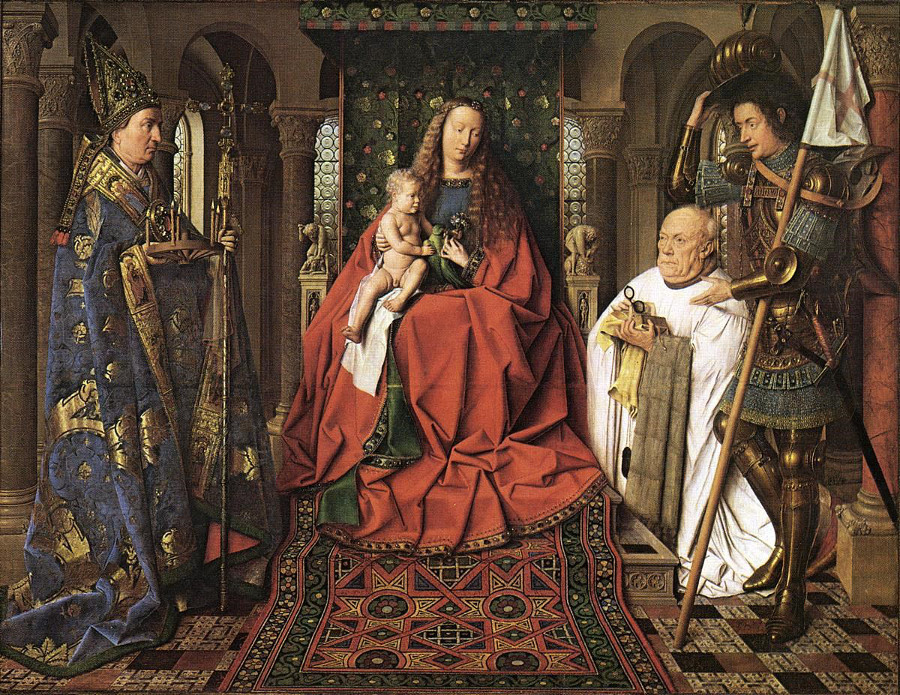

11. Jan van Eyck. Madonna. (At Bruges.)

This picture was painted

in 1436. You will admire the tenderness of expression in the Madonna, no

less than the characterisation of this figure (the Canon, Georg van der

Pole). It reveals a wonderful observation of Nature and a strong sense of

character, with all the primitiveness of the period — needless

to say. The next picture was painted by Jan van Eyck in Spain, whither

he had been summoned.

12. Jan van Eyck. The Waters of Life. (Prado. Madrid.)

Observe the Gothic

architecture in the background. To represent the Waters of Life, the Well

of Life, in connection with the Sacrifice of the Lamb, was natural to the

ideas of that time. Once more, as in the former picture, you have the

motif of God the Father with Mary and St. John.

Here, however, it is

transferred more into the spirit of the Southern Art — not

unnaturally, as the picture was painted in Spain.

In the former picture we

had the same theme treated with more of the Northern character.

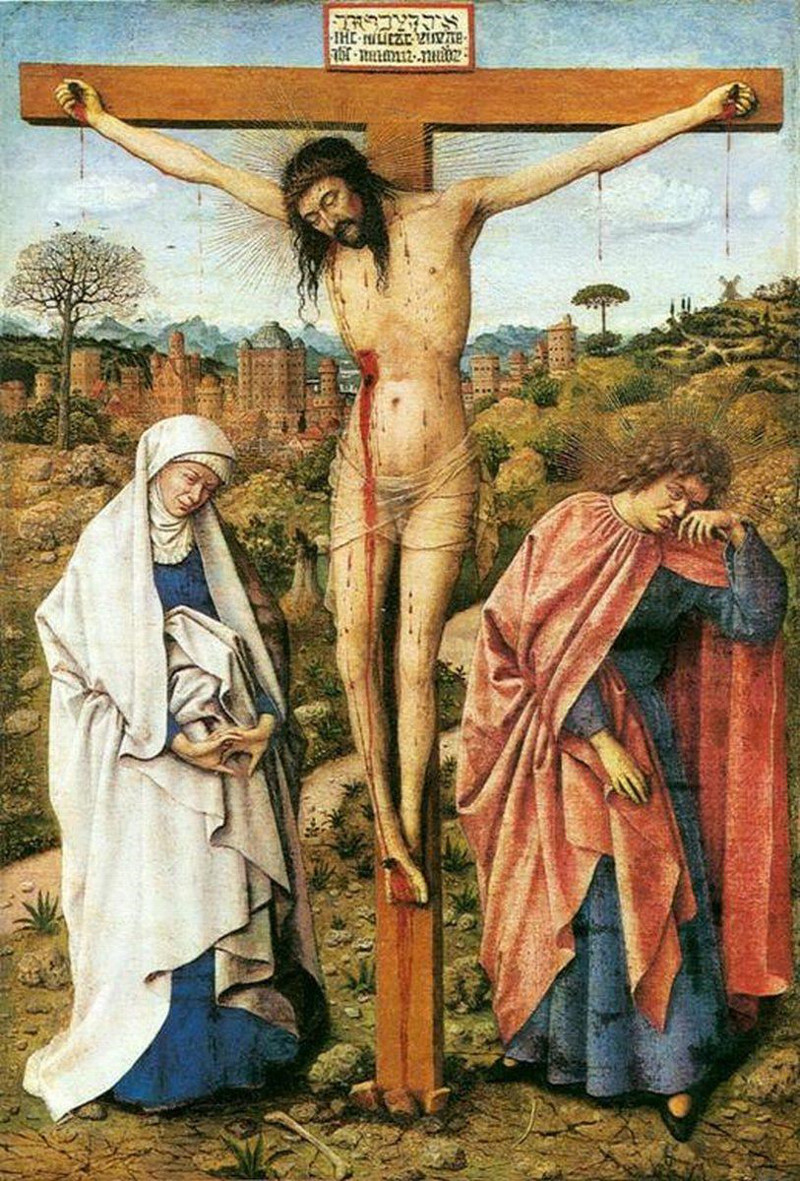

13. Jan van Eyck. The Crucifixion. (Berlin.)

Notice how the characteristic

qualities come to expression in this picture. The human element far

outweighs the Biblical tradition. Only the subject, the occasion, we

might say, is taken from that quarter. See with what deep human sympathy

the Biblical story is re-awakened, as it were. Here it is not merely

the prevalent idea that it is meet to represent in pictures what the

Bible tells. The whole event is felt again and re-experienced in the

highest degree. It is scarcely conceivable — (pointing to the

figures of Mary and St. John) — that a Southern artist would have

placed this line, and this, side by side. Here, however, the painter's

chief concern is not with the composition, but to give an impression

of real inwardness — to realise the inner experience. And then

we must say that the effect of this line, and this line, together, is

most wonderful, characterising as it does the different moods of the

soul.

We now give two examples

of secular subjects by the same artist.

14. Jan van Eyck. The Betrothal. (National Gallery.

London.)

This picture shows very

clearly how great was the artist's power of characterisation and

expression. Our last picture by Van Eyck shows the attempt to get still

further in the way of portraiture;

15. Jan van Eyck. The Man with the Carnation. (Berlin.)

Here you will see with great

distinctness, the artist does not care at all to conceive what a man

should be like; he does not work out of any such impulse, but as he

sees the human being — whatever presents itself to his vision

— this he reproduces.

We now come to a

contemporary artist who outlived Van Eyck by a few years — the

Master of Flémalle, as he is called.

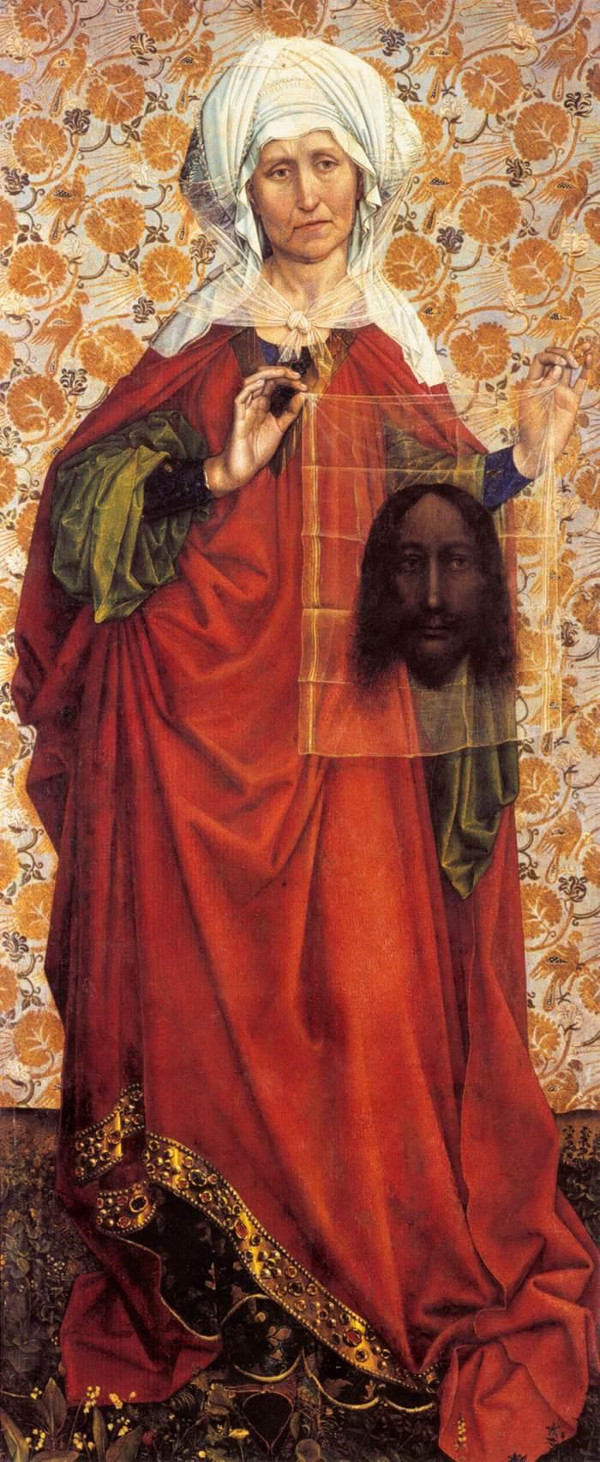

16. Master of Flémalle. St. Veronica. (Frankfort.)

In him we recognise a seeker

inspired by somewhat the same impulse as the Van Eycks, yet influenced far

more from France. He recognise these influences in the “line.”

There is a kind of echo of artistic tradition. In Van Eyck's work we

feel that everything is born out of an elemental inner need. Here, on

the other hand, there is already an underlying opinion — this

thing or that ought to be represented in such or such a way. Though

they are not by any means predominant in his work, still we can see

the Master of Flémalle accepts the principles of certain aesthetic

traditions. In the former artist you will not easily find, for example,

this peculiar position of the hand, nor this peculiar treatment of facial

expression. These elements in the picture are undoubtedly to some extent

determined by certain influences from France. An atmosphere of elegant

grace is poured out over these figures, which you will not find to this

extent in the figures of Van Eyck.

17. Master of Flémalle. Death of the Virgin.

(London.)

Characteristically —

this picture shows the Christian legend transplanted into the artist's

present time. These pictures were painted about the thirties of the

15th century.

We now come to Van der

Weyden, who — like the former artist, received certain influences

from France. Still, he contains all those elements which mark him out

clearly as a follower of the Van Eycks.

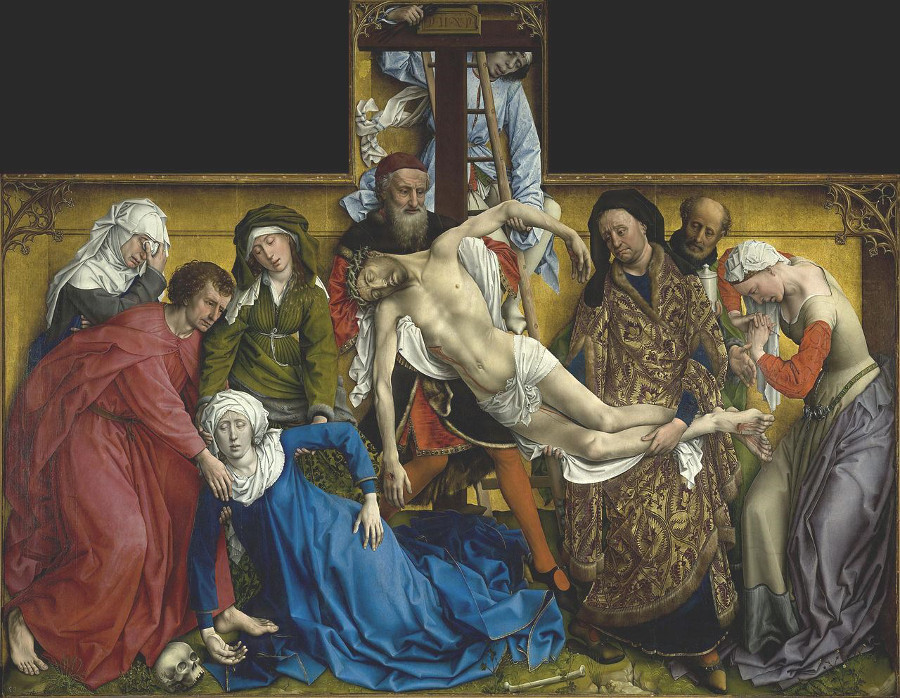

18. Rogier van der Weyden. Descent from the Cross. (Berlin.)

Already in this picture

you will see a characteristic difference. There is an essentially dramatic

life in this, whereas we might say Van Eyck is purely ethical. Van Eyck

places his figures quietly side by side; they influence one another,

but there is no one all-pervading movement. Here, however, in Van der

Hayden's work, there is a certain drama in the working together of the

figures. It is not merely ethical.

19. Rogier van der Weyden. Descent from the Cross. (Prado.

Madrid.)

The same subject, treated

once more by the same artist. And now a picture taken from the Christian

legends.

20. Rogier van der Weyden. St. Luke painting the Madonna.

(Munich.)

Here you see the Evangelist

St. Luke, who, as the legend has it, was a painter, painting Mary and

the Child.

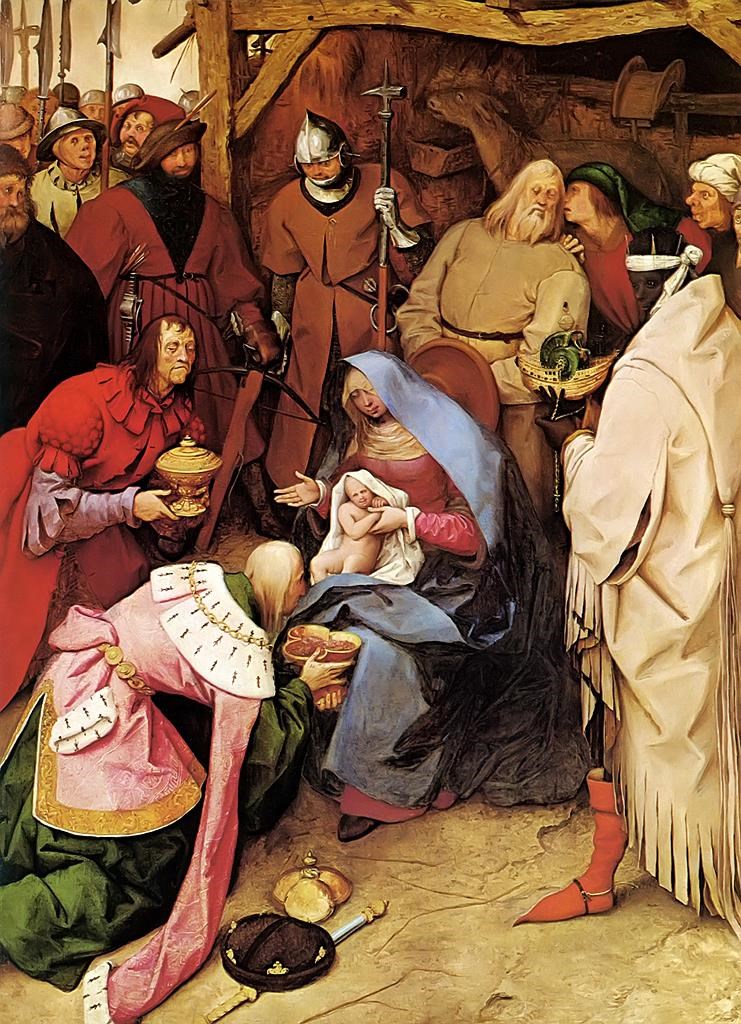

21. Rogier van der Weyden. Adoration by the Three Wise

Men. (Alte Pinakothek. Munich.)

One of these is King Philip

of Burgundy; this one, who is just taking off his hat, is Charles the

Bold. If only by this external feature, the whole scene is very much

transferred into the artist's immediate present. For the Kings who come

to worship the Child, he takes the figures of princes more or less of

his own time.

22. Rogier van der Weyden. Charles the Bold. (Berlin.)

Here, then, we have a portrait

by Van der Weyden. All these artists attained — a certain perfection

in the art of portraiture.

We now come to Petrus Christus:

23. Petrus Christus. The Annunciation (wings of an Altar-piece) (Berlin.)

24. Petrus Christi. The Birth of Christ

The Angel and Mary (The

Annunciation) and the presentation of the Christ Child. Petrus Christus

works more or less equally along the lines of Van der Weyden on the

one hand, and the Van Eycks on the other. These pictures were painted

about 1452 — the middle of the 15th century.

In the following pictures

we come increasingly to the more Northerly Dutch element, where the

landscape is developed to greater and greater perfection. The next picture

is by Dieric Bouts the Younger. And now, a picture extraordinarily

characteristic of this stream in Art:

25. Dieric Bouts. Adoration by the Three Wise Men. (Alte

Pinakothek. Munich.)

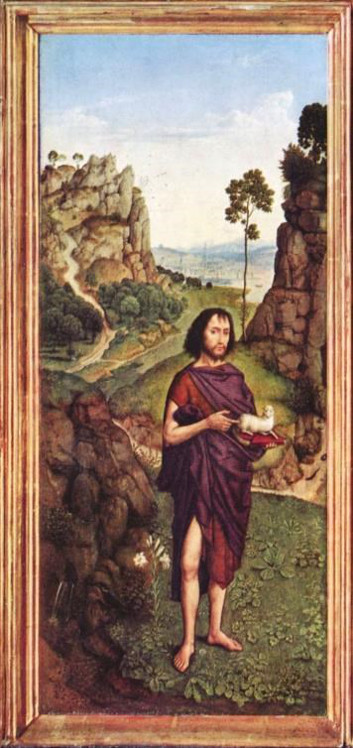

26. John the Baptist and Christopher

On one side is the Baptist;

on the other side the Christophorus — the Christ-Bearer. Truly,

there comes to expression here the full and immediate human inwardness,

and with it the landscape that belongs to it. In Dieric Bouts you will

especially notice this art — to place the human being fittingly

within the landscape of open Nature.

The realistic representation

of things is working its way through more and more. Man as an artist

becomes more and more able to find, in the direct reproduction of Nature,

what he has been striving for along this path.

27. Hugo van der Goes. Portinari Altarpiece, c. 1475.

(Uffizi. Florence.)

Truly, Realism has here

reached a high degree of perfection. The same subject again:

28. Hugo van der Goes. Adoration by the Shepards, 1480

(Berlin.)

29. Hugo van der Goes. St. Anthony and St. Matthew.

Below are the Donors of

the picture. By the same artist:

30. St. Margaret and St. Mary Magdalene. (Ste. Maria

Novalis. Florence.)

31. Hugo van der Goes. The Death of Mary. (Academy.

Bruges.)

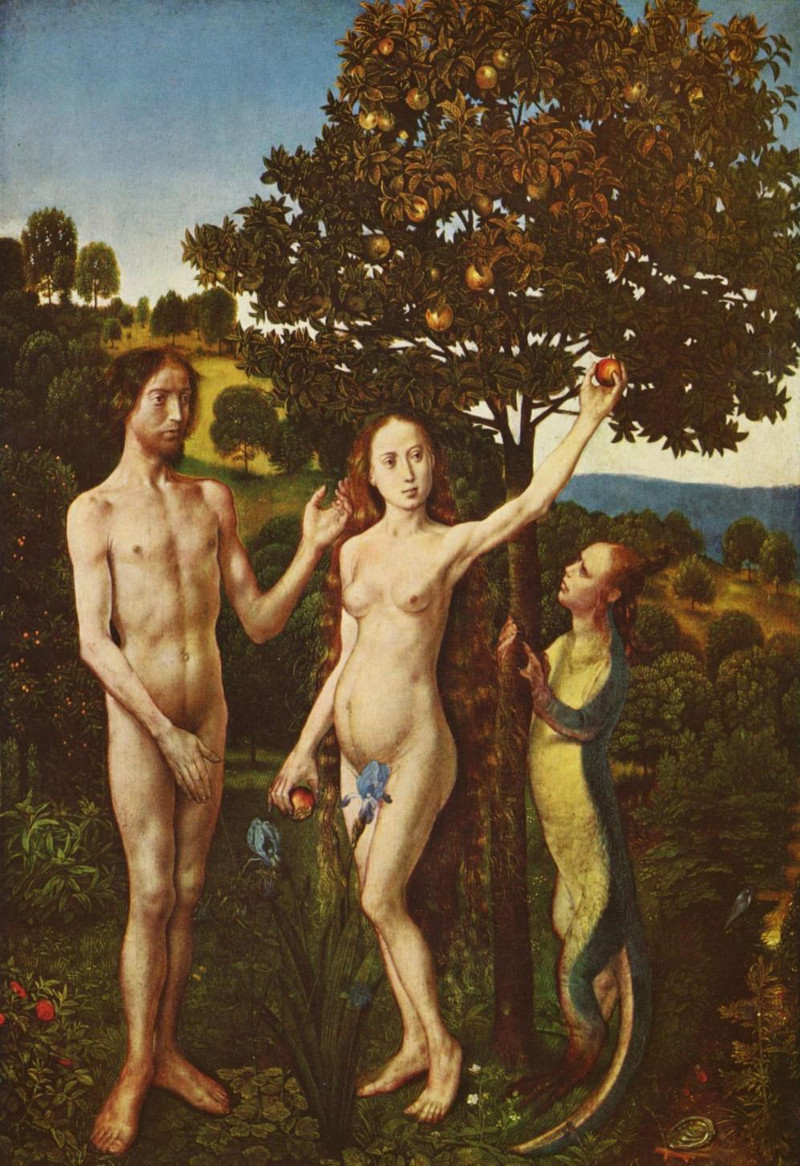

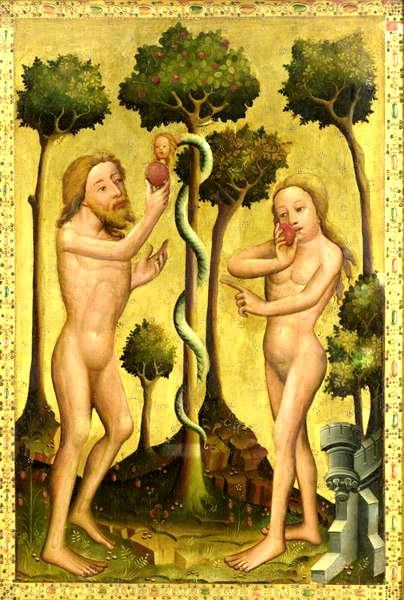

32. Hugo van der Goes. Adam and Eve. The Fall. (Vienna.)

The Art of that time —

as I have said on previous occasions relating to Meister Bertram —

did not picture a mere snake, but tried to portray the Luciferic

element.

33. Meister Bertram. The Fall (Hamburg.)

That the snake itself —

the existing physical snake — should have been the Tempter, is

an invention of the most modern naturalistic materialism.

We now come to the artist

who, educated in the School of Van der Weyden, represents, in a certain

sense, its continuation. He was known in the School as Der deutsche

Hans. I refer to Hans Memling.

34. Hans Memling, Madonna Enthroned. (Uffizi. Florence.)

This artist was born at

Mainz. We shall, if possible, in the near future, show some examples

of Upper German paintings, which have their own characteristic peculiarities.

Its tendencies are quite evidently present in this picture; but for

the rest, Memling had absorbed all that was then living in the Art of

the Netherlands, including the influence that came over from France.

The next picture is also by Hans Memling.

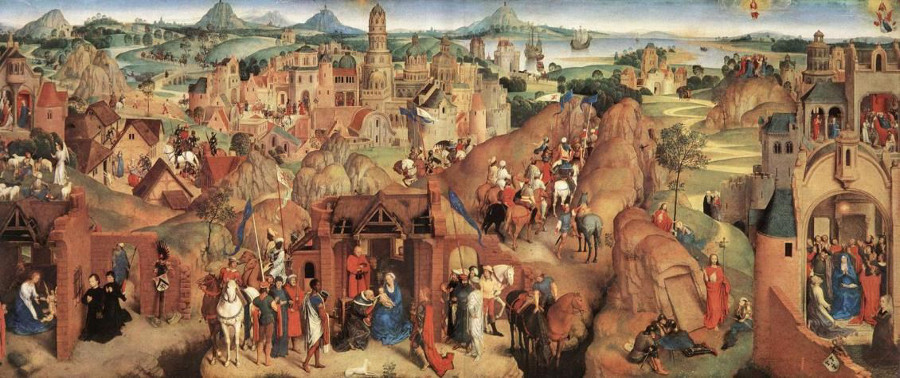

35. Hans Memling. The Seven Joys of Mary. (Munich.)

— a motif which was

also familiar to those times. The various events connected with the

life of Mary are here portrayed. Unfortunately it is too small in this

reproduction to recognise the details very clearly.

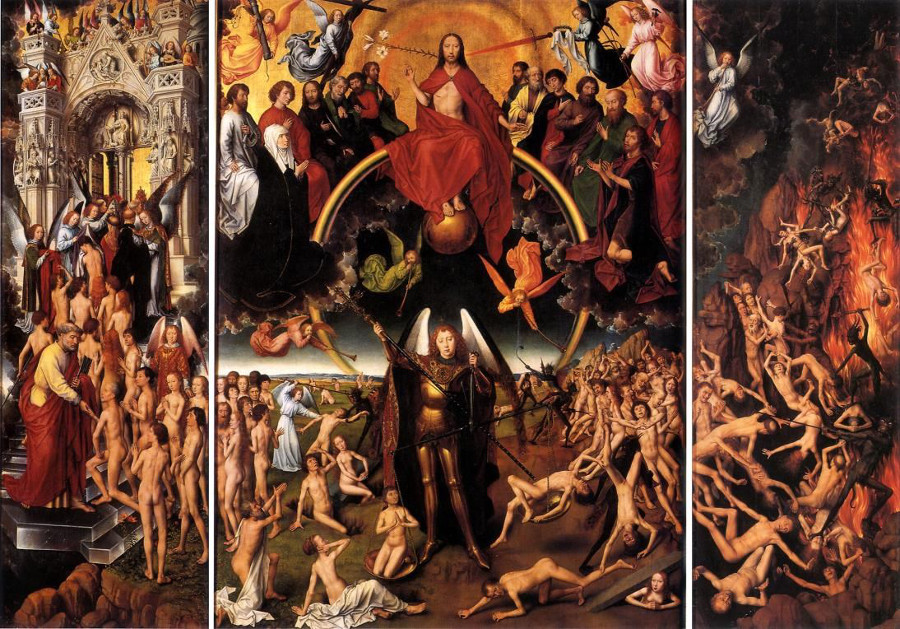

36. Memling. The Last Judgment. (Marienkirche. Danzig.)

A characteristic picture

by Memling. With real genius, in his own way, he brings to expression

his conception of the Last Judgment. There is a certain angular quality

about it, and yet the whole event is permeated with humanity, with inward

feeling. The picture is note at Danzig. A powerful trader stole the

picture — but, being a pious man also, he afterwards bequeathed

it to a church in Danzig.

He will also acquaint

ourselves with Memling's portraits. You will see that all this School

achieves a greatness of its own in representing the human

individuality.

37. Memling. Portrait of a Man. (Berlin.)

The expression of the

qualities of the soul in this face is, indeed, remarkable. This is a

well-known picture at the Hague.

38. Memling. Portrait. (The Hague.)

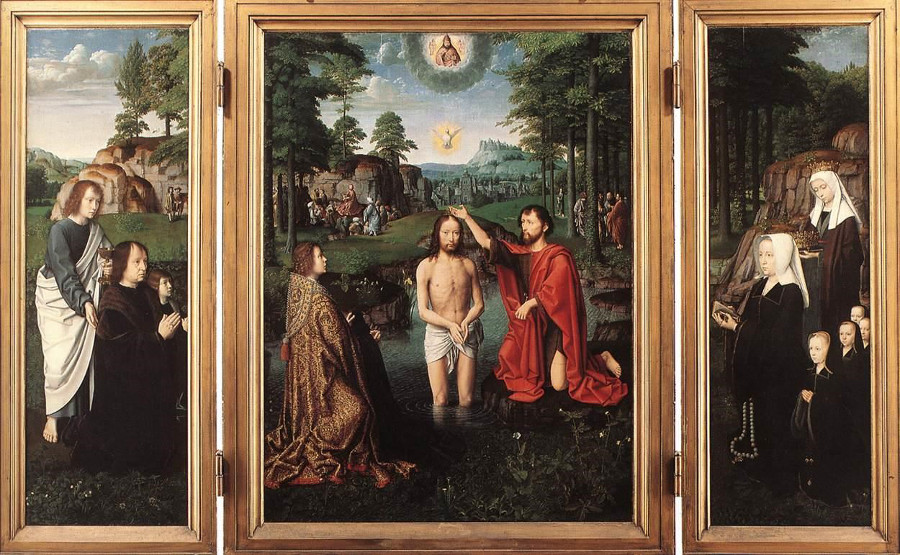

We come now to the later

artists who no longer show quite the same freedom and simplicity, but

a certain contortion and inner complexity. David, for instance, was

born in 1400; he came from Holland. Hitherto, we may say, we have had

before us the pre-Reformation period in Art; the artist we shall now

show brings us already very near the Reformation.

39. Gerard David. Adoration of the Magi. (Munich.)

Here you will recognise

how strongly the Southern influence is already working in the element

of composition.

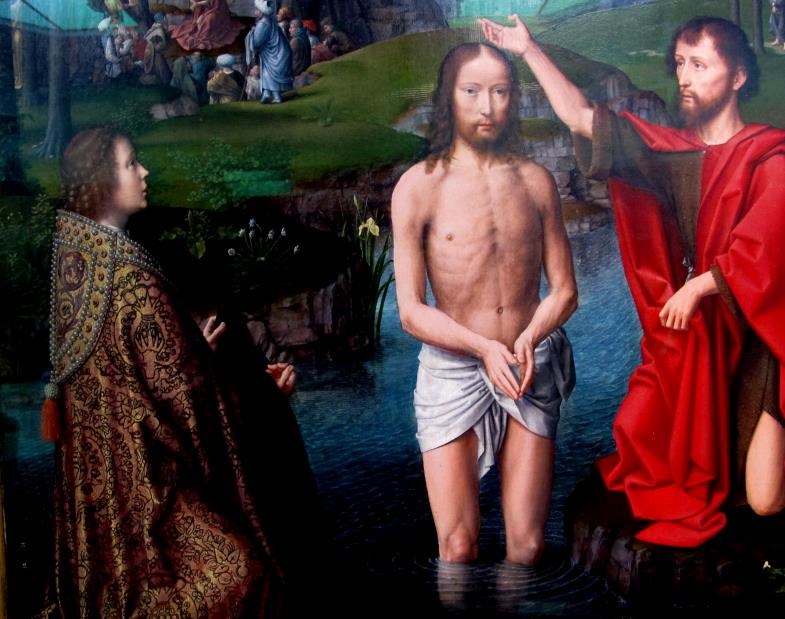

40. Gerard David. Baptism of Christ. (Bruges.)

41. Gerard David. Madonna and Christ, with Angels. (Rouen.)

42. Gerard David. Mary and Child

The next is by an artist

who was in a sense only a kind of imitation of David. We now come to

Geertgen, who, though he dies at the early age of twenty-eight, does,

indeed, bear within him all the peculiar characteristics of this epoch.

43. Geertgen. Holy Family. (Amsterdam.)

44. Geertgen. The Holy Night. (Berlin.)

As we go forward into the

16th century, other elements mingle more and more with what was

characteristic of the Van Eyck period. We come now to Hieronymus Bosch.

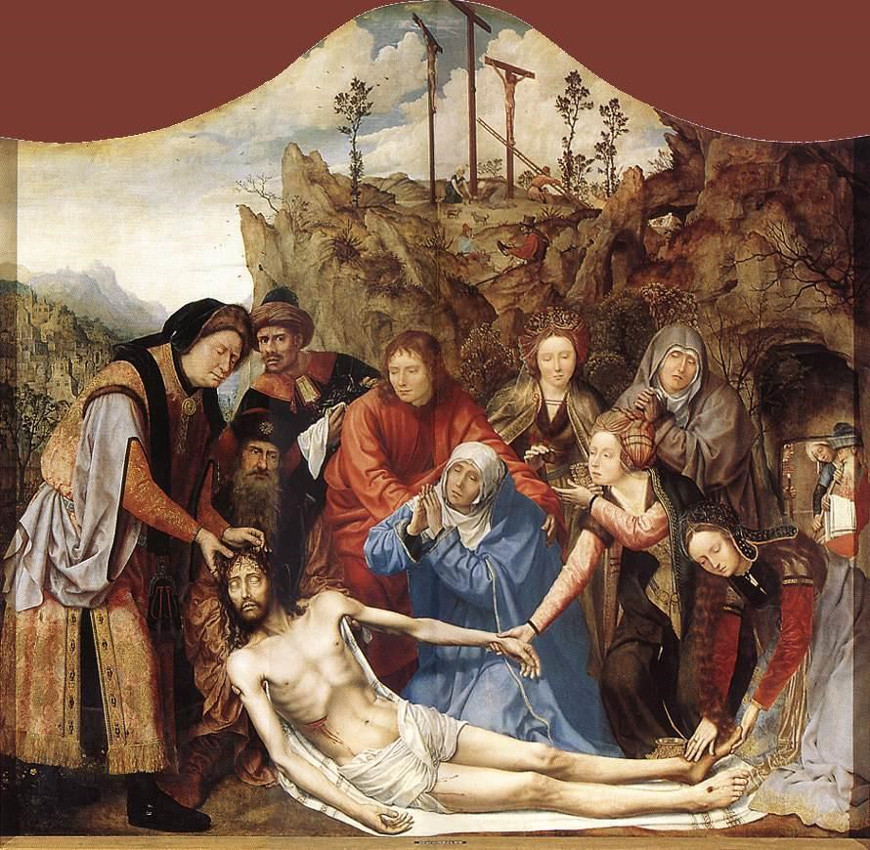

45. Hieronymus Bosch. Descent from the Cross.

In his work we find a strong

element of composition. Also we have no longer the mere naturalistic

observation. His work is permeated with a fanciful, fantastic feeling

— so much so, that he becomes the painter of all manner of grotesque

and “spooky” subjects.

46. Hieronymus Bosch. Christ carrying the Cross.

47. Hieronymus Bosch. Hell. (Prado. Madrid.)

The fantastic element is

mingled with all that he had learned in this direction.

Now we come to Quentin Matsys,

in whom the element of composition is already strongly paramount. Indeed,

this is already in the 16th century.

48. Quentin Matsys. Holy Family, 1509. (Brussels.)

49. Quentin Matsys. Mourning for Christ. (Antwerp.)

Here you see quite deliberate

composition. In the next picture we shall see how this feeling for

composition combines with that for individual characterisation even where

there is less intensity of form, or movement, in the group.

50. Quentin Matsys. The Money-Changer and His Wife.

(Louvre. Paris.)

We now come to an artist who

reveals the characteristics of the period especially in his

landscape-painting — Joachim Patinir. It was at this time and from

these regions that landscape-painting first developed and found its way

into the full artistic life. Only from this time onward was it really

discovered for the life of Art.

51. Patinir. The Flight into Egypt. (Madrid.)

52. Patinir. The Flight into Egypt. (Berlin.)

53. Patinir. The Baptism of Christ. (Vienna.)

I beg you to look at this

especially, from the point of view of landscape-painting. Such landscape

treatment could naturally only originate in the age of attempted

naturalism; only then does landscape begin to have a real meaning

for Art.

54. Patinir. Temptation of St. Anthony. (Prado. Madrid.)

The next is a painter quite

definitely of the 16th century. I spoke just now of the

“Burgher” element. He carries it still further, even into the

sphere of the peasantry. His works are born of the elemental simplicity

of the people. Nevertheless, all manner of other influences enter into

them — Italian influences, for example. Thus he strangely unites

his elemental Dutch simplicity with a very marked Renaissance feeling.

I refer to Pieter Brueghel — born in 1525.

55. Brueghel. The Pious Man and the Devil. (Naples.)

56. Brueghel. The Blind Leading the Blind. (Paris. Louvre.)

57. Brueghel. The Fall of the Angels. (Brussels.)

58. Brueghel. The Way to Calvary. (Vienna.)

And another Biblical subject

by the same painter.

59. Pieter Brueghel. The Adoration of the Magi. (London.)

With that, we will finish

for today.

|