Lecture IX

Sculpture in Ancient Greece and the Renaissance

Andrea Pisano,

Giovanni Pisano,

Niccola Pisano,

Andrea della Robbia,

Giovanni della Robbia,

Luca della Robbia,

Brunelleschi,

Carrey,

Donatello,

Ghiberti,

Michelangelo,

Verrocchio.

Dornach,

January 24, 1917

I have often quoted Goethe's

saying, when he felt in Italy the echo of the nature of Greek Art. I

may remind you of it once again today, now that we shall show a few

representations of Greek sculputre. Goethe was writing from Italy to

his friends in Weimer. He had seen something in Italy of the Grecian

Art, and he had divined still more. He had made acquaintance with it.

And he wrote: After this experience he had become convinced that in

the creation of their works of art the Greeks proceeded according to

the same laws by which Nature herself proceeds — and he himself

was on the track of their discovery.

This saying of Goethe's

always seemed to me of deep and lasting significance. Goethe at that

moment divined that something was living in the Greeks, in intimate unison

with the laws of the great Universe. Alread before his journey to Italy,

he had been trying to discover the principle of universal evolution and

becoming. He had done so, above all, in his Theory of Metamorphosis. He

found that the manifold forms of Nature can be referred to certain typical

or fundamental forms, in which is expressed the spiritual Law and Essence

that underlies the outer things. He started, as you know, from Botany

— the study of the Plant world. He tried to perceive the growth of

the plant in this way: A single fundamental organ, whose basic form he

recognised in the leaf, undergoes constant metamorphoses. All organs are

transformations of this one. Not only so, but having thus begun, he sought

to understand the several plant species as diverse manifestations of one

archetypal form, the primary plant.

Likewise he looked for

a connecting thread throughout the world of animals. We have often spoken

of this work of Goethe's. But, as a rule, we have not a ufficiently

vivid conception of what he intended. We are wont to conceive things

too abytractly, and we do so in this case. Goethe, if I may put it thus,

wanted to take hold in a really living way of the life of living things,

in their organic metamorphosis. He wanted to discover the principle

on which Nature works. In so doing, he was, indeed, steering straight

towards what must be the characteristic of the Science of the fifth

post-Atlantean age, even as that which the Greeks conceived and expressed

in their works of art was characteristic of the fourth.

In this connection I have

often called upon you to observe what is recognisable in the Golden

Age of Greek Art, and notably of Grecian sculpture, in so far as it been

preserved for us. The Greek artist created from an altogether different

starting point. He had a certain feeling. To exprec it in our fully

concrete way, we must describe it thus: He felt how the Etheric Body

in its living forces and mobility underlies the forms and movements

of the Physical. He felt how the Etheric is manifested or portrayed

in the forms of the Physical Body, while in the movements of the latter

the living forces that abound in the Etheric Body come to expression.

The Greek art of Gymnastics,

the Greek Athletics, were built on this foundation. Those who partook

in them were to gain thereby a real feeling of what lives invisibly

within the visible being of man. And in his plastic art the Greek wanted

to portray what he himself experienced in his own nature. All this,

as I have often said, grew different in later times, for afterwards

men copied what they saw before them with their eyes, what they had

outwardly before them. The Greek copies what he felt within himself.

He did not work after the model as was done in later times — (whether

they do so more or less obviously or indistinctly is not the point). To

work from the model is only a peculiarity of the Fifth post-Atlantean age.

Nevertheless, in this very age there murst arise a new view of Nature, for

which the living starting-point is given in Goethe's

“Metamorphosis.”

True, there are weighty obstacles, as yet, to such a view of Nature.

In this sphere, as in all others, materialistic prejudices stand in

the way of a healthy conception of existence. The latter will have to

work its way forth in the overcoming of these hindrances. We have to

witness in our time things that are little noticed yet — movements

that tend in the long run to brutalise even the artistic life. Goethe

recognised in a beautiful way the connection between Truth in knowledge

or science and Truth in Art, in practice. Science to him was still a

living life within the Spirit.

Among the hindrances in this

regard is one thing to which — if able to look more deeply into all

the impulses of hindrance and of progress in our timei — we cannot

give a pleasant name. I refer to what are now called sports and games,

athletics and the like, which — if we look more deeply — are

also largely among the forces of hindrance in modern civilisation. I can

describe them in no other way, than as a tendency to degrade civilisation

to the level of the ape. Modern sports and athletics — themselves

an outcome of the materialistic conception of life — represent,

as it were, the other pole. At the one pole, materialism tends to conceive

man as a merely more perfect ape, while at the other pole — through

many of the activities that fall under the heading of sport —

they are working hard to turn him into a kind of carnivorous monkey.

The two things run parallel with one another. Needless to say, modern

sports and games and athletics are regarded as a great sign of progress.

Indeed, they are often thought of as a kind of resurrection of the spirit

of ancient Greece. But in their real essence they can only be described

as working towards the ideal, to “monkeyfy” the human race.

What can become of man if he proceeds along this path of modern sports,

etc? Precisely a “monkeyfied” man, whose chief distinction

from the real monkey will lie in the fact that the latter is a vegetarian,

while monkeyfied man — presumably — will be a carnivorous

species of monkey. The hindrances that face us in the civilisation of

today must sometimes be described grotesquely; otherwise we do not describe

them strongly enough to bring them home — however little —

to the people of today. It is quite in keeping with the propensities

of our time: On the one hand theoretically, they are at pains to understand

Man as a more perfect ape, while on the other hand in practice they

work to bring out the apishness of Man. For if that human being were

developed, who is the underlying ideal of the extremer movements in

sports and games today, a scientist could truly describe him in no other

way, than in all essentials as an offshoot of the ape-nature.

We must think truly on

these matters, to gain some understanding of those noble forms of Humanity

which underlay the Golden Age of Grecian Art. It was inevitable in the

Fifth Post-Atlantean age, for man to leave behind him his life within

the spiritual ... The ancient Greek was living in it still. When he

moved his hand, he knew that the Spiritual — the etheric body

— was in movement. Hence, too, as a creative artist, in all that

he imparted to the physical material, he strove to create, as it were,

the expression of what he felt within him — the movement of the

etheric body. The man of today must go a different path. By way of outward

vision, contemplation, — combined with the living Imagination

of the weaving of the Ethereal in the organic reelm, — he must

bring ancient Greece to life again on a higher level, permeated this

time by conscious knowledge, according to the true impulses of the fifth

post-Atlantean age. In an elementary way, Goethe was striving towards

this end in his Theory of Metamorphosis.

Goethe lived with his whole

being in this striving towards a living conception of the Spiritual

in the world. For this reason he was glad to refresh and strengthen

himself by all that came to him from the study of Greek Art.

To understand the art of

ancient Greece in its proper nature — its characteristics entirely

a product of the mood of soul of the fourth post Atlantean age —

we must start from such ideas as we have just set forth. In this respect

it is interesting to see how the Greek Art found its way. Few of the

original works have been preserved. Most of them are only handed down

to us through later copies. It was with the help of later copies that

a man like Winckelmann, in the 18th century, strove so wonderfully to

recognise the essence of the art of ancient Greece. Winckelmann, Lessing

and Goethe, in the latter half of the 18th century, tried to express in

words the essence of Greek Art — tried to find their way back, to

re-discover it. And we may truly say: Greek Art in its essence, once it

is really grasped, can bring salvation from the perils of materialism.

It would take us too far

afield if I were to give you even an outline sketch of the real history,

the occult history of Greek Art. Only this much may be said, in connection

with the illustrations we shall see today. Even in the early works of

the Fifth or of the end of the Sixth century

B.C., the relics of which

have come down to us; the underlying foundation which I described just

now is clearly recognisable. Albeit, in that early period the Greeks had

not yet the ability to express through the material what they experienced

within, nevertheless even in the archaic forms, imperfect as they are,

we can see that the artist's creation is based on a feeling of the inner

life and movement of the etheric body. By this means the Greek could find

the way to raise the human form so marvellously to the Divine. The Greek

was well aware that the figures of his Gods were based on real Being in

the ethereal universe. Out of this there arose quite instinctively (for

everything in that time was more or less instinctive) the need to

represent the world of the Gods and all that was connected with them, in

such a way that the outer form was the human form idealised. The point

was by no means merely to idealise the Human — that is only the

idea of an age that fails to understand the real depths. Through

the idealised human form they were able to express what lives and weaves

in the ethereal life.

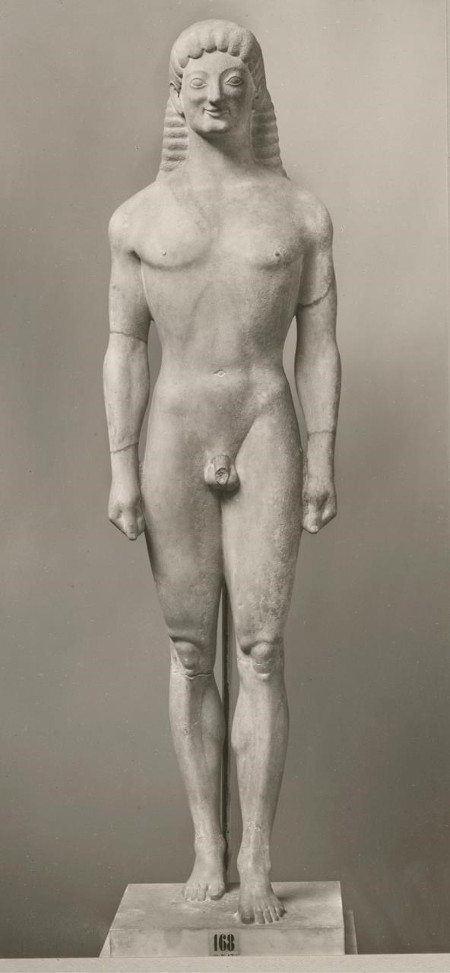

In the earliest figures

we still see a certain stiffness. But out of this, in their Golden Age,

the Greeks evolved the power to express in the outer physical form the

etheric human being. In the earliest pictures we shall still see a certain

stiffness; but even here it can be seen that the shaping of the limbs

proceeds from a true feeling for the ethereal in movement.

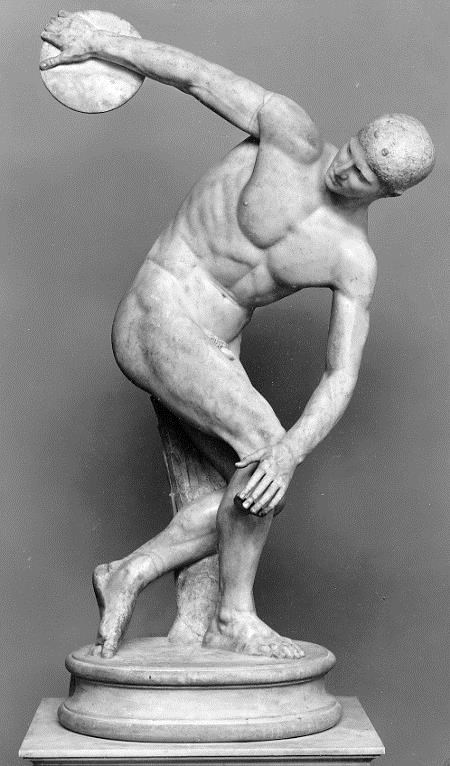

Then as we go on to Myron

and bring some of his works before our souls, we shall see how what

first came to expression only in the forming of the limbs, begins to

take hold of the whole body. In Myron we already see how when an arm

is moved — or represented in movement — it means something for the whole

breathing organism, the forming of the chest. The human being as a whole

is felt through and through. And this must have been the case to the

highest degree in Phidias and his School and in Polycletus — in the

Golden Age of ancient Greece.

Thereafter we find a gradual

descent of Art from this sublime feeling of the ethereal. Not that the

ethereal is left out; but they now try to master the actual forms of

Nature, they follow the forms of Nature more faithfully, more humanly

and less divinely. Nevertheless, the forms are still an expression of

the living etheric movement within.

In looking at the several

pictures, we shall be less concerned to discuss the individual artists;

we chiefly want to see the gradual evolution of the Grecian Art as a

whole. Nor does it matter so much, whether we speak — as the historians

of Art are wont to do — of a decline in the latest works. In the earlier

period the body was conceived, as it were, more in position, thus a

certain restfulness or repose pervades the older works. Movement itself

is conceived as though it had come to rest. We have the feeling that

the artist endeavors to represent the body in such a way that the position

in which the figure is might be a lasting one. The later artists strive

for a more dramatic quality, holding fast the moment of time in the

progressive movement. Thus there is more of movement in the later works.

It is, after all, a mere matter of choice — arbitrary human choice —

whether we call this a decline or not.

After these few remarks

we will see some illustrations, and whatever more there is to say can

be said in connection with the single works that will be shown.

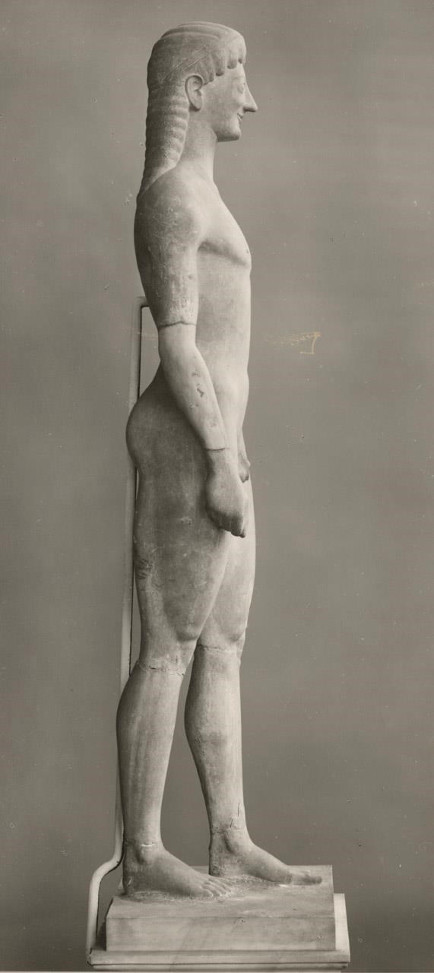

1. Apollo of Tenea. (Glyptothek. Munich.)

This is of an early period

— about 600

B.C. Observe how the limbs, especially, are

permeated with the ethereal ... One feature of the earliest Greek

sculpture is often emphasized: the smile, as it is called, about the lips.

In time to come this will be recognized as arising from the effort to

represent not the dead human being — the mere physical body —

but really to seize the inner life. In the earliest period they could do

this in no other way than by this feature.

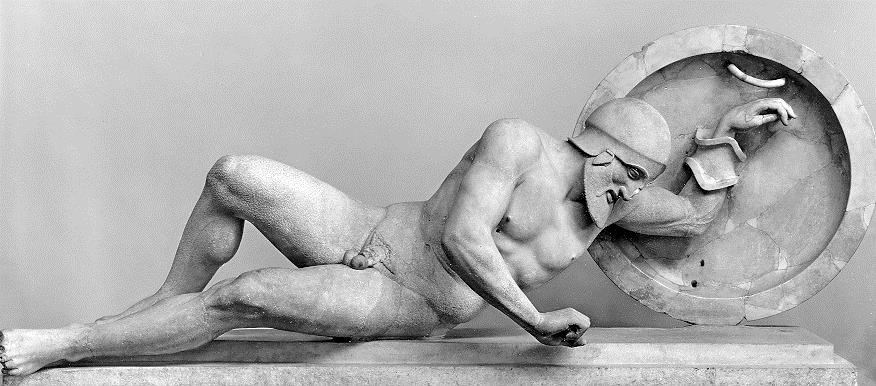

2. Dying Warrior. Eastern Pediment. Temple of Aegina.

(Glyptothek. Munich.)

These works of art in the

Doric Temple at Aegina were done as a thank-offering for the Battle

of Salamis. They chiefly represent battle-scenes. Dominating the whole

is the figure of Pallas Athene, which we shall see presently. This dying

recumbent figure is a beautiful example of the figures that are found

in this temple. The figures are grouped in the pediment. It is most

interesting to see the composition, the perfect symmetry. The figures

are distributed to the left and right with the most beautiful symmetrical

effect.

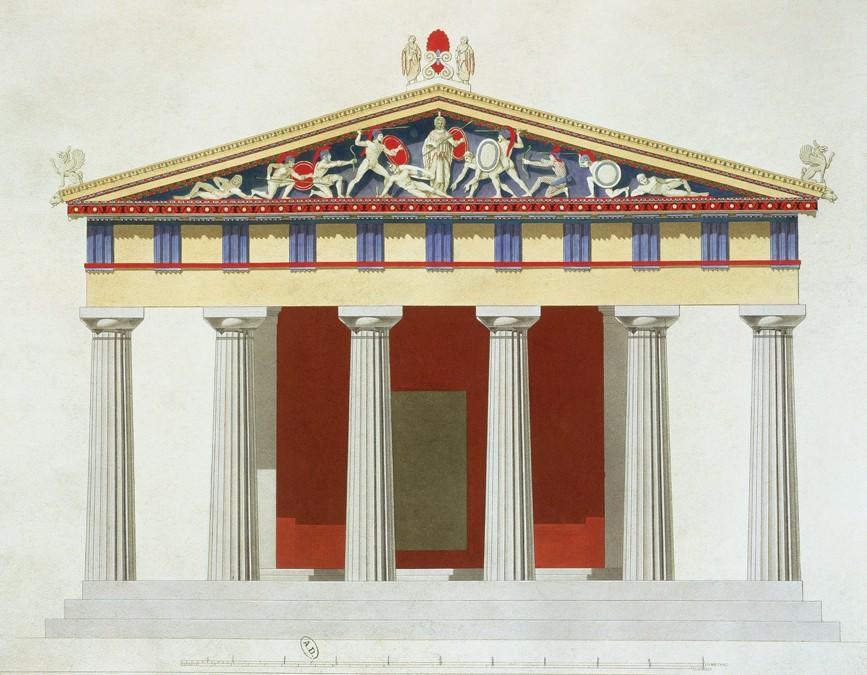

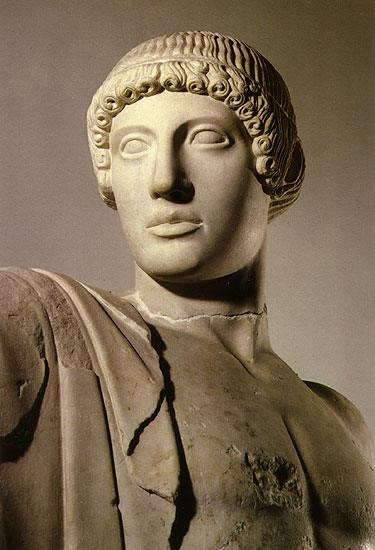

3. Pallas Athene from the Pediment of the Temple at

Aegina. (Glyptothek. Munich.)

4. Reconstruction of the Western Piedemont of the Aphaia

Temple.

These works take us to the

beginning of the 5th century B.C.

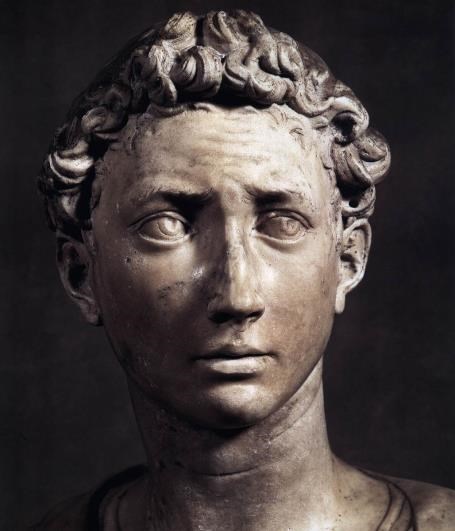

5. Head of a youth.

6. Charioteer from Delphi

7. Runner (middle of the 5th century

B.C.)

And then I ask you to note,

as with Myron — as we come in to that age that one can denote

as the pinnacle — as with Myron, that a very different treatment

of the body arises, in that he no longer separates, what even here is

still the case, but he knows how to treat the whole body in connection

with the limbs.

8. Discus Thrower

Thus we stand in the middle

of the 5th century and find in such a shapes a tryly high degree of

perfection in the direction, we have tried to characterize.

And now we come, or are

already in, to the Age of Periclean. From the time of Phidias, of whomwe

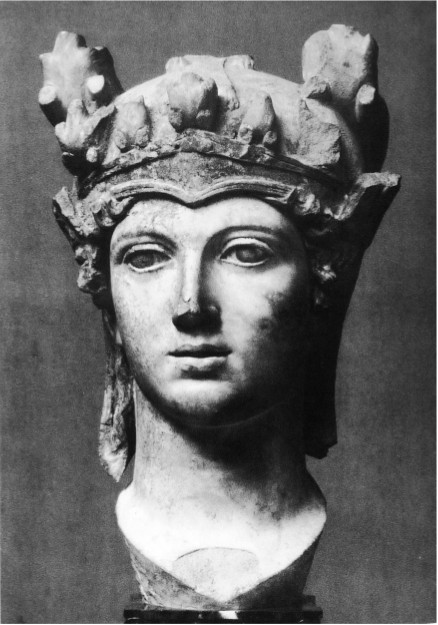

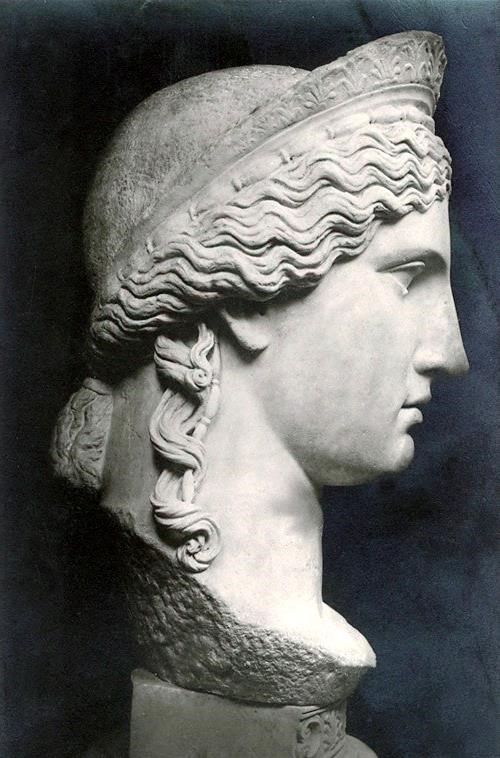

unfortunately know very little, you have the so-called Athena Lemnia:

9. Athena Lemnia

10. Head of Athena

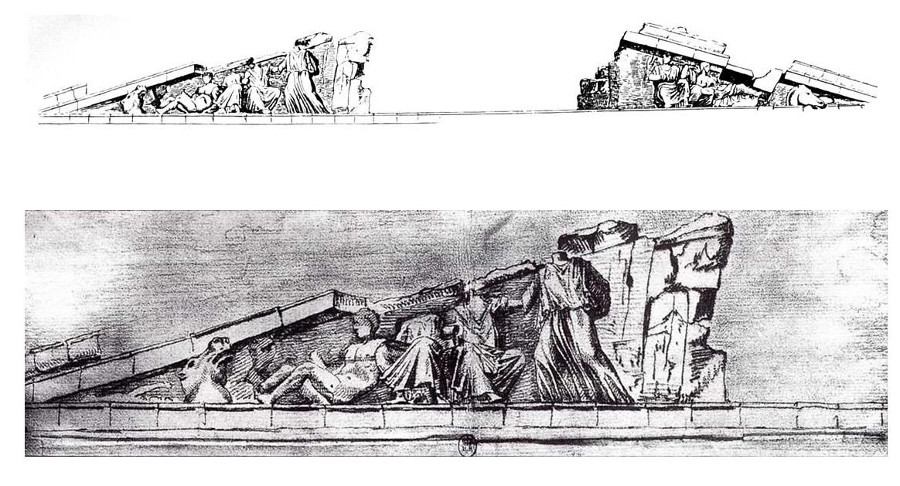

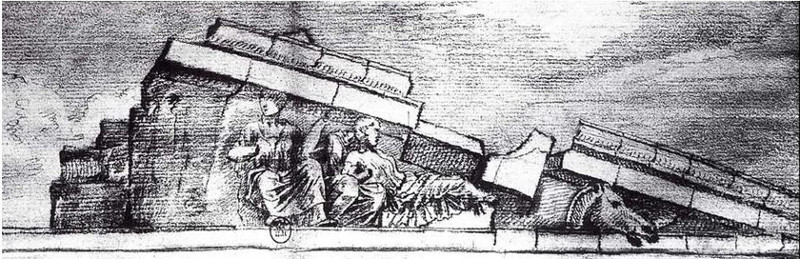

We will now give a few

examples of the famous Parthenon. You may read the interesting story of

these figures in any History of Art. The greatest of them have in all

probability been lost. We can only gain some idea of them from the

drawings made by the Frenchman, Carrey, in the 17th century. Subsequently

they were largely destroyed by the Venetians, and only the relics were

discovered by Lord Elgin in the 19th century.

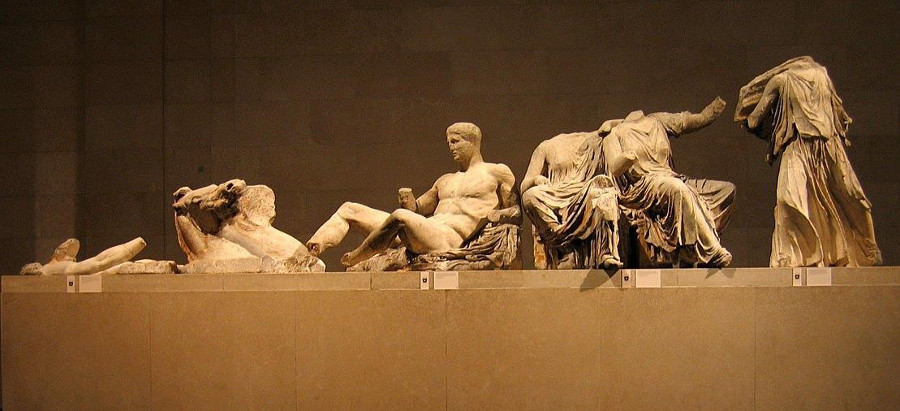

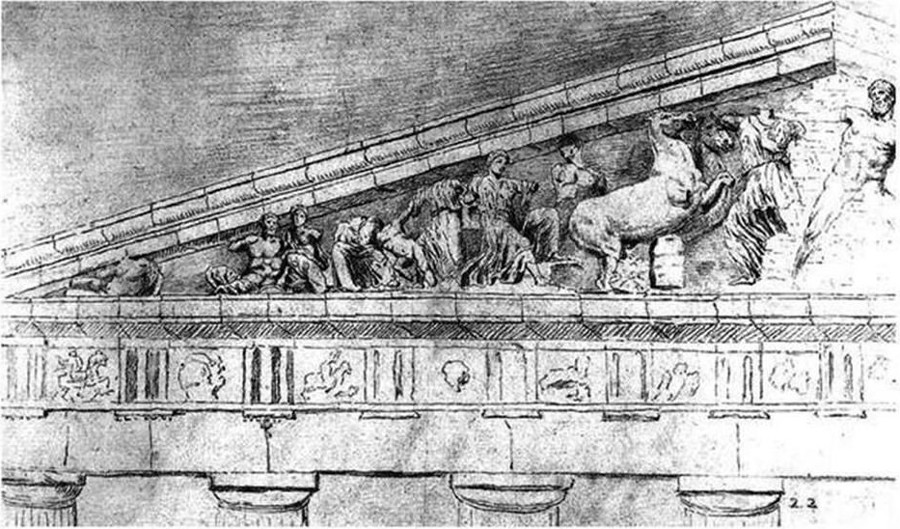

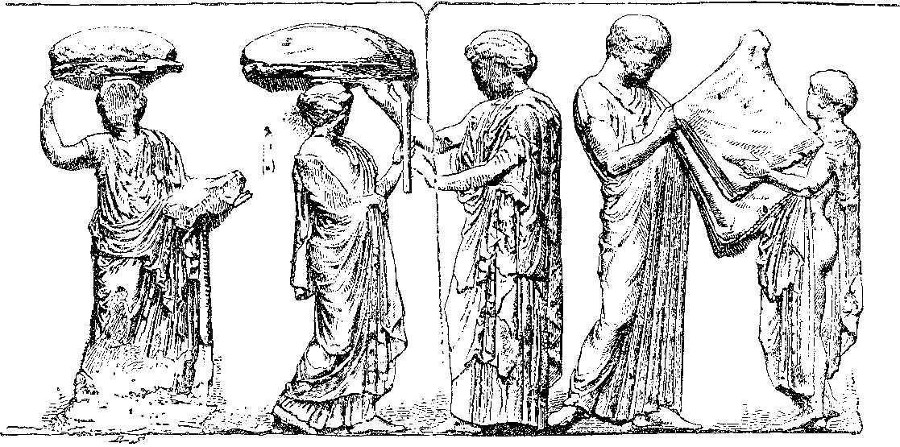

11a. Drawings of the eastern pediment.

11b. Remains of the left side of the eastern pediment. (Bristish

Museum. London.)

11c. Reconstruction of the figures in the last photo.

11d. Hestia, Dione, and Aphrodite from the right side of

the eastern pediment. (British Museum, London.)

11e. Far right of the eastern pediment.

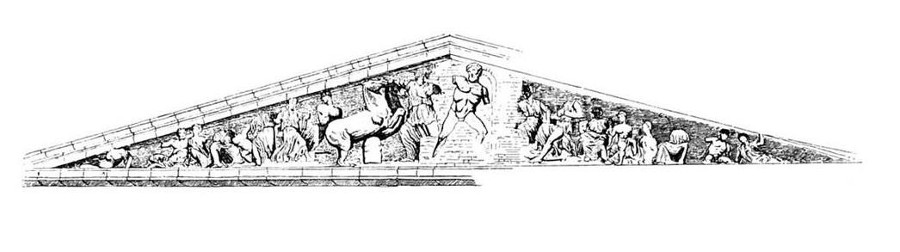

Now for the Parthenon western pediment:

11f. Drawings of the western pediment.

11g. Reconstruction of the western pediment.

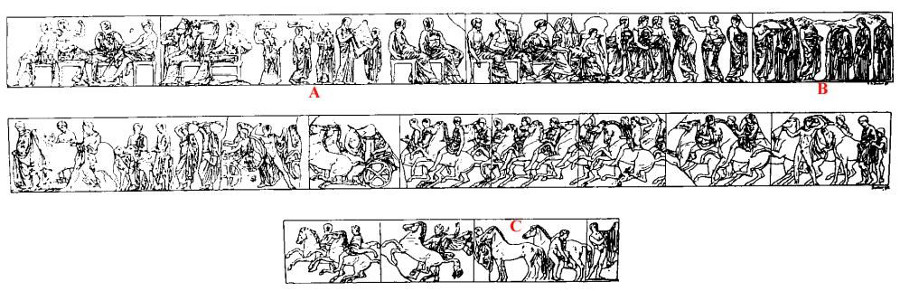

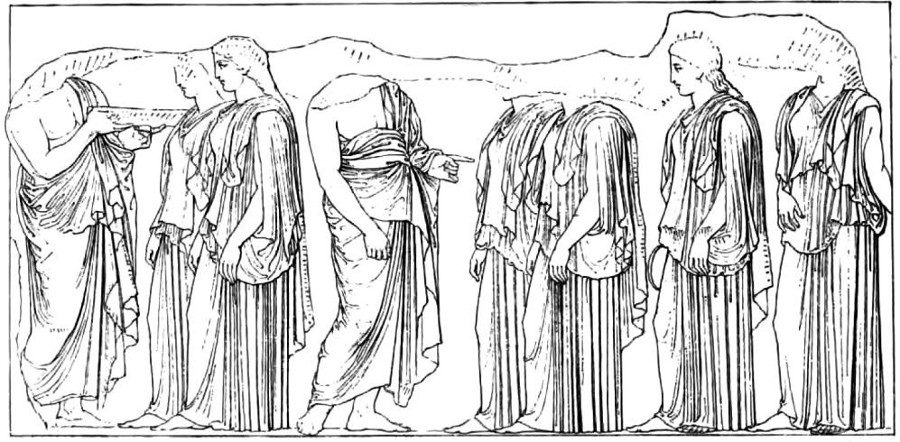

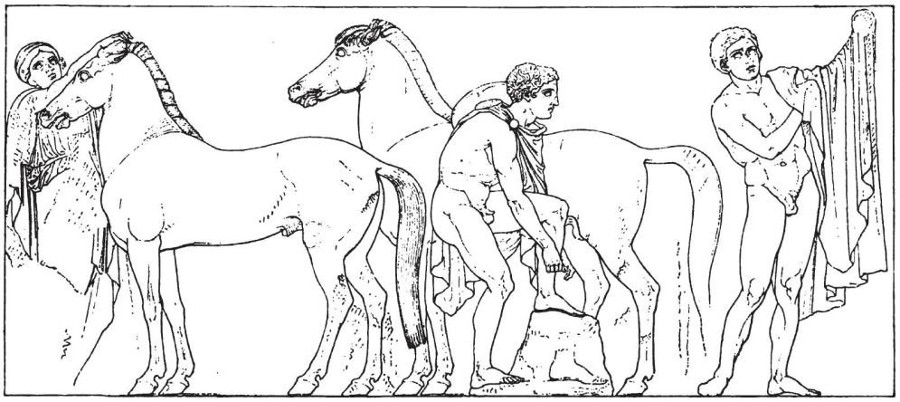

The Parthnon Friezes:

12a. Drawings of the Friezes.

12b. Calvary. (Western Frieze.)

We may assume that these

works were mostly executed in the presence of Phidias himself by his

pupils. The next group is from the Eastern Frieze:

12. Poseidon Group. (Eastern Frieze.)

With Phidias, indeed, all

that was typical of Greek Art was already given. The stamp, the signature,

as it were, was now given to the bodily figure, as it should be represented

in Art. The way in which Phidias and his pupils saw it lived on for

a long time. It was felt that the line of the face, the features, the

movement of the limbs, the flow of the drapery and so forth, should

accord with what was evolved in this ideal age.

Through all the traditions

this was handed down, even into the times when they were able to imitate

quite superficially what had lived so strongly in this Golden Age of the

Art of ancient Greece. Unhappily, the greatest works have been destroyed.

It is no longer possible to gain by outer vision a conception of Phidias'

greatest masterpieces, which were transcendent and sublime. We must

realise that in the 18th century, when Goethe and others, stimulated

by Winckelmann, entered so deeply into the essence of Greek Art, they

could only do so with the help of poor, late imitations. Truly, great

intuition was necessary to penetrate into the nature of Greek Art through

the poor imitations that were then available. And if we really try to

feel the truth about these things we cannot but admit: In the time when

Goethe was a young man, or when he travelled in Italy, there was still

quite a different instinctive feeling for Art than later in the 19th

century, — let alone the 20th. For otherwise it would have been

impossible for these late imitations to inspire the lofty conceptions

of Greek Art which lighted forth in Winckelmann or in Goethe.

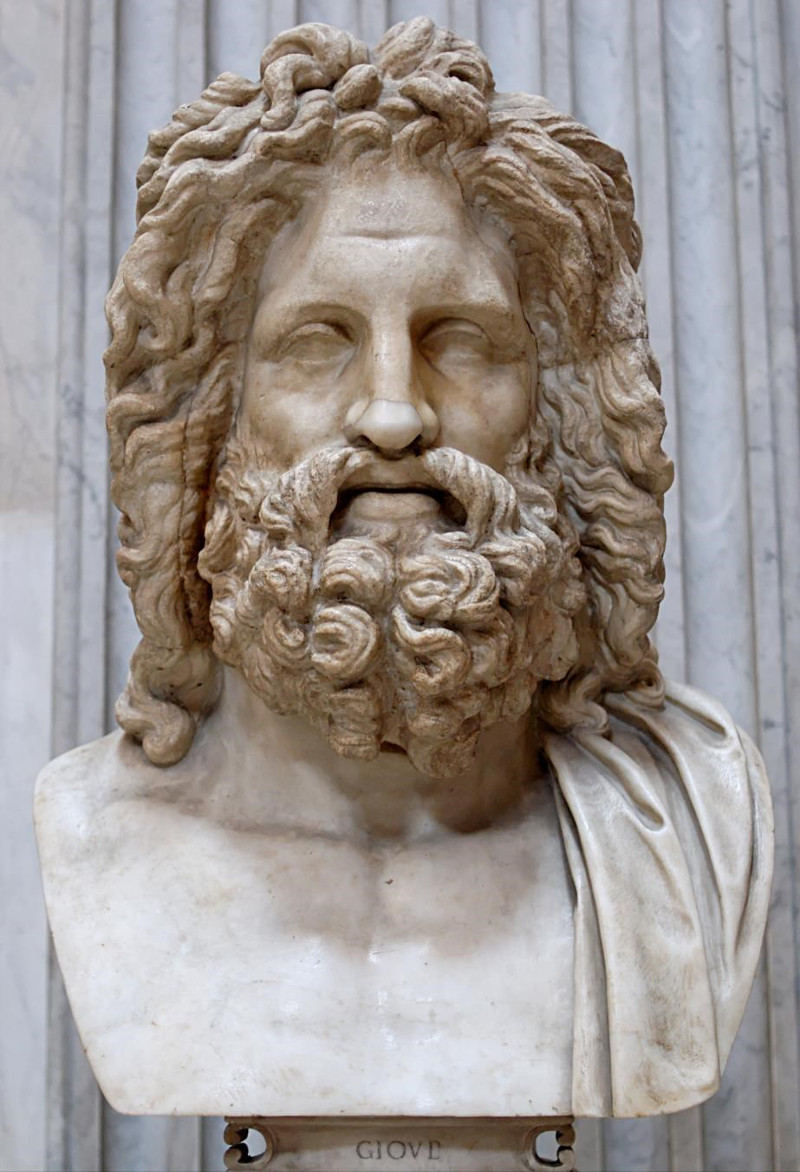

Look, for instance, at the

next, the head of Zeus, which is to be seen in Rome:

13. Zeus of Otricoli. (Vatican. Rome.)

14. Athena

Here you can see something

like a later continuation of the type that was evolved in the time of

Phidias. This is, of course, a later imitation, though undoubtedly it

still appears with a certain grandeur, — With a far less grandeur

they imitated the Hera type which had been evolved by Polycleitus. And

as to the famous Pallas Athene, which is also to be seen among these

statues in Rome, here I must say the imitation has become insipid, fatuous.

Indeed, this figure shows already the type of the later imitations of

Pallas Athene. These things even become a little reminiscent of

fashion-plates! We can but divine how magnificent were the works from

which these later imitations were derived.

In this head of Zeus you

see the tradition that was handed down from Phidias.

14a. Zeus

14b. Profile of Zeus.

And now we will go back

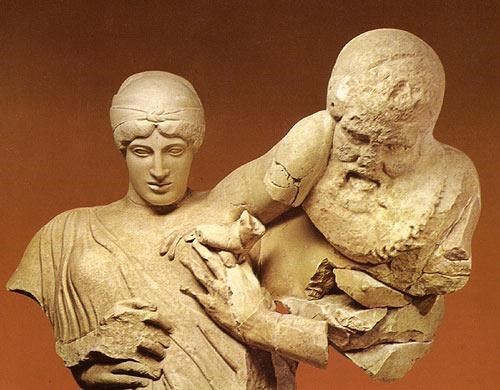

to the figures from the temple of Zeus at Olympia. Here, too, the composition

is magnificent:

15. Western Pediment. Temple of Zeus at Olympia.

16. Figure of Apollo.

The next, too, is from the

School of Phidias: —

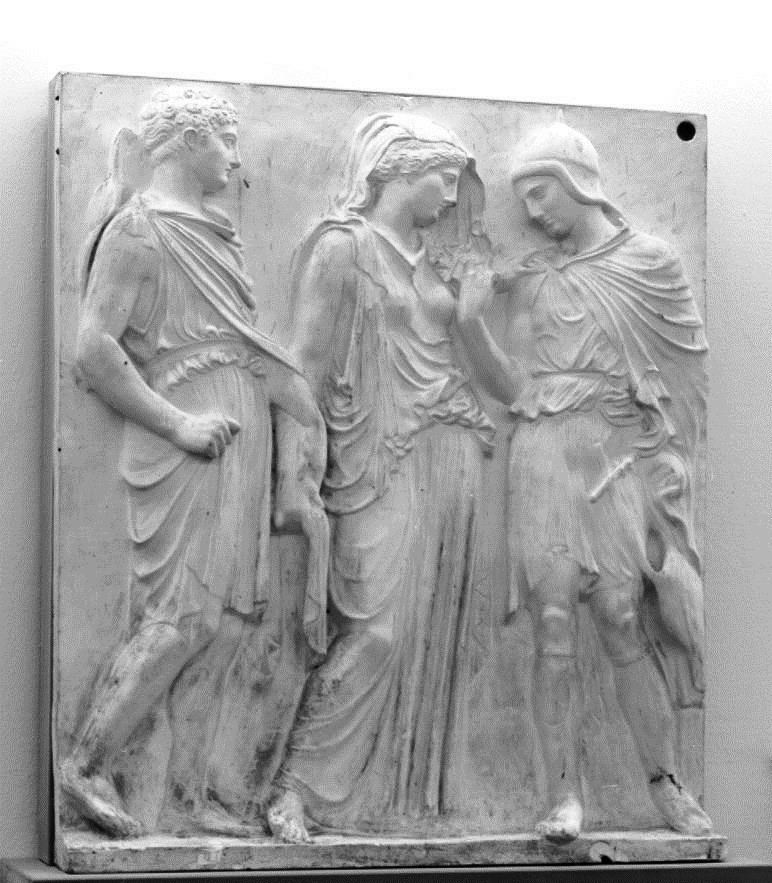

17. Orpheus Relief. (Museum. Naples.)

We remember how Phidias

was accused by his fellow-citizens of stealing gold for his gold-and-ivory

statue of Athene. His “grateful” fellow-citizens threw him

into prison.

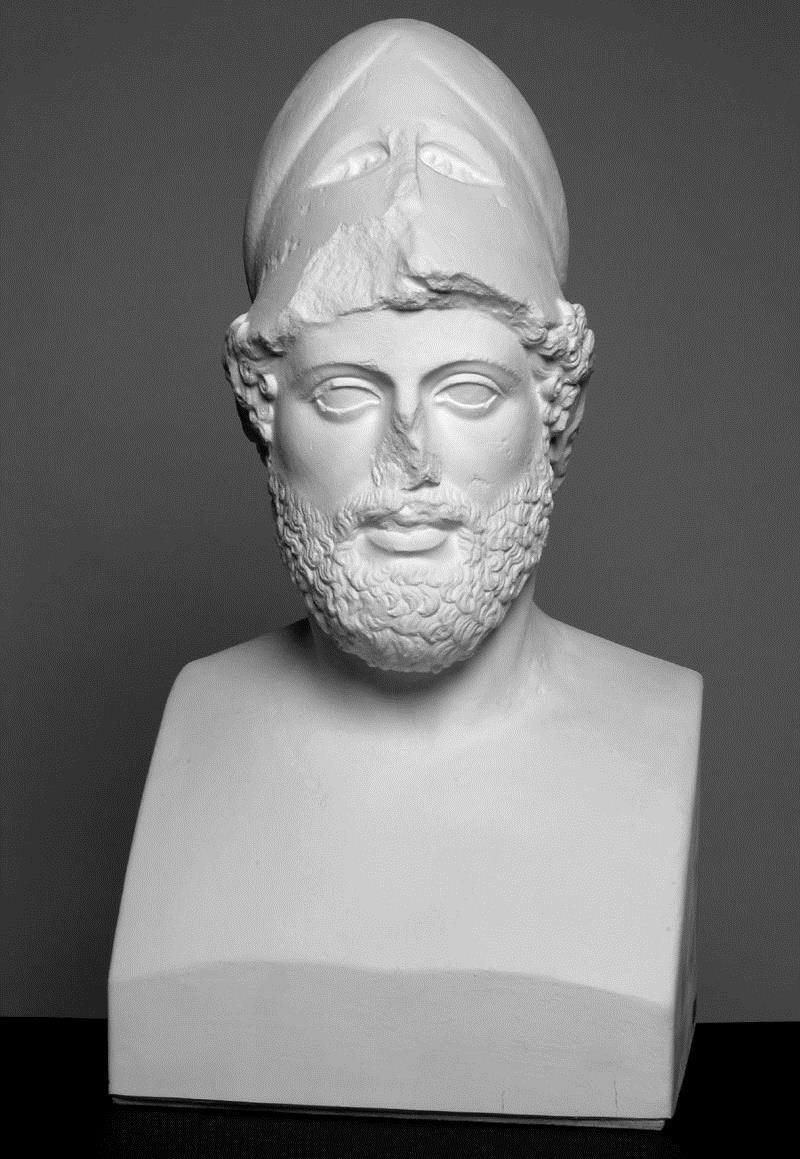

18. Bust of Pericles. (Berlin.)

Truly an ideal conception

— lifted far beyond the sphere of portraiture.

The next is perhaps a work

of Phidias' youth. —

19. Amazon.

Here we will insert a work of Polycleitus: —

20. Amazon.

Myron and Phidias are the

artists of the Golden Age of Grecian Art; they, indeed, created the

traditions.

21. Amazon.

Another Amazon. The next

is more difficult to date; it represents about the turn of the 4th and

5th centuries

B.C. We insert it here to show that ancient Greece

was quite capable of producing something of the character of Genre: —

22. Boy, extracting the Thorn from his Foot. (Rome.)

And now we gradually come into

the age of which I tried to indicate just now that the whole conception

is lifted down into a more human realm, even though the figures be still

the figures of the Gods. Take the following, for instance: —

23. Aphrodite of Cnidos. (Vatican, Rome.)

Although it is the figure of

a Goddess, it is brought down into a more human sphere. The sublimity of

the earlier artists is made more human. We see this already in Praxiteles.

This picture represents the so-called Aphrodite of Cnidos. Praxiteles

brings us to the 4th century

B.C. In connection with this we will also

show the

24. Demeter of Cnidos. (British Museum.)

It breathes the same spirit.

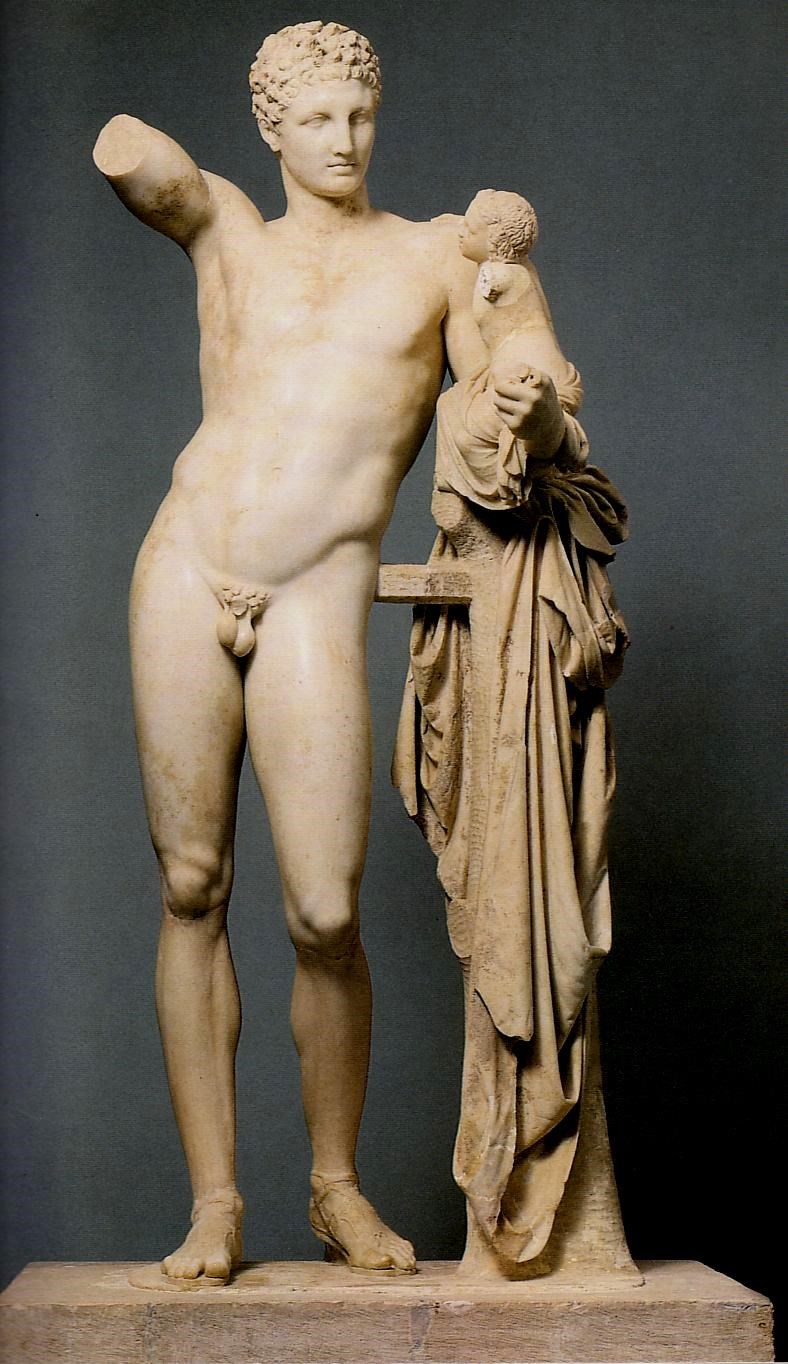

The next is the Hermes of Olympia:

25. Hermes of Olympia, (By Praxiteles.) — holding

the Dionysos child in his left hand.

26. Satyr, by Praxiteles. (Capitol. Rome.)

To the same epoch belongs

the famous Niobe Group, — Niobe losing all her children through the

wrath of Apollo.

27. Figure in Flight, from the Niobe Group. (Vatican.

Rome.)

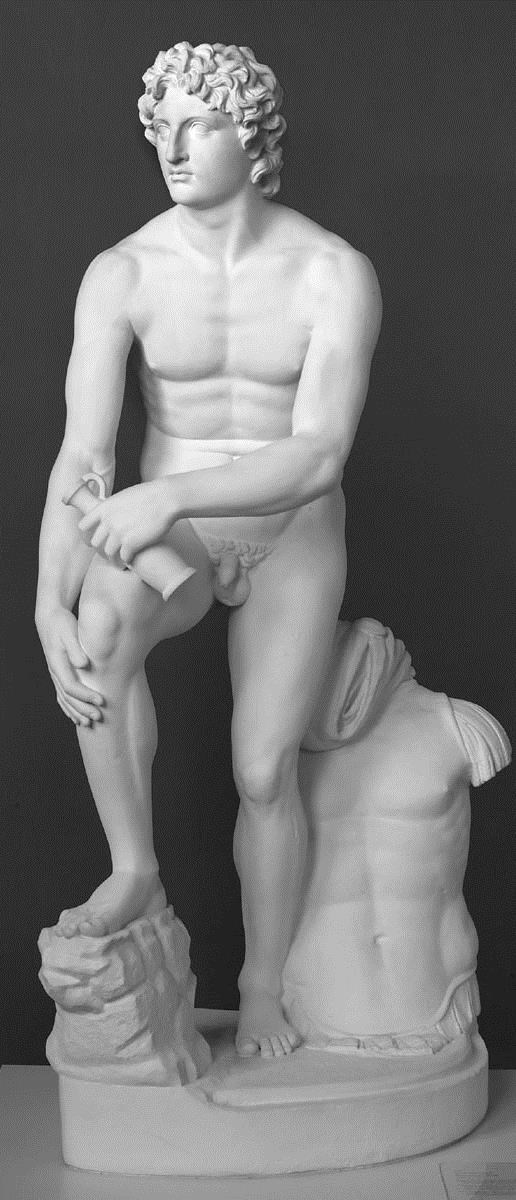

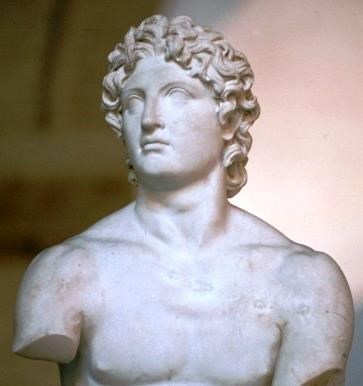

Going on into the 4th century,

we come into the Alexandrian age. Lysippus actually worked in the service

of Alexander the Great.

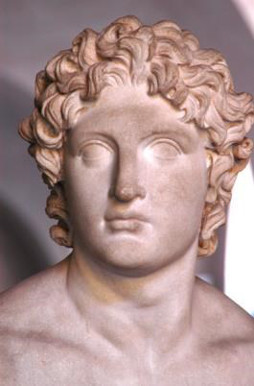

28. Bust of Alexander. (Louvre. Paris.)

29. Hermes. (Museum. Naples.)

30. Youth, in Adoration. (By Lysippus.) (Berlin.) His

arms are lifted up to Heaven in reverence, in prayer.

31. Alexander the Great. (Munich.)

Here we already see the

descent of Art from the Typical to the Individual — though in

the Grecian Art the process nowhere went as far as in the later epochs.

32. Medusa Head. (Glyptothek. Munich.)

33. Sophocles. (Vatican. Rome.)

This status reaches back

again to the best, ideal tradition of the older times; it reminds us

of the Golden Age. We might equally well entitle it: The Poet, as such.

This is symbolised by the rolls of script which are put there of set

purpose. Compare this with the figures that now follow, tending more

or less towards a portrait likeness in each case. You will see how they

strive away from the ideal type, towards the quality of portraiture.

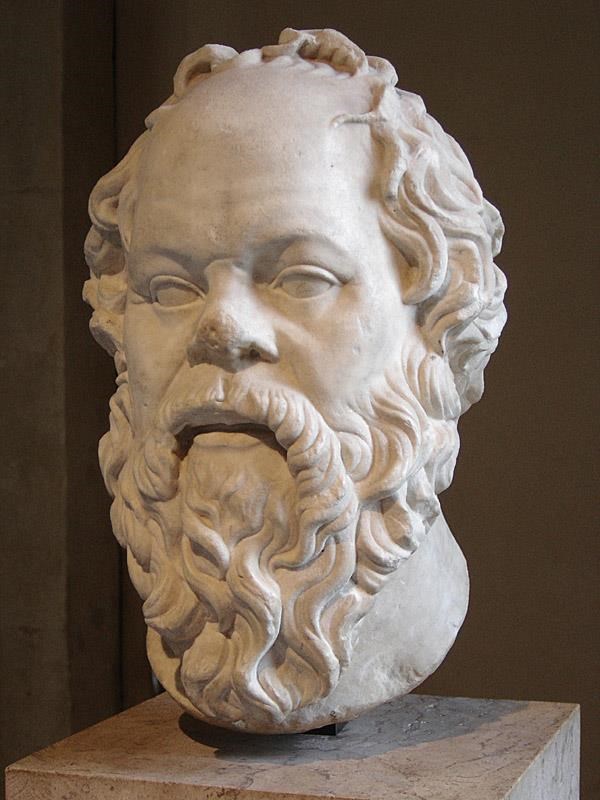

34. Socrates.

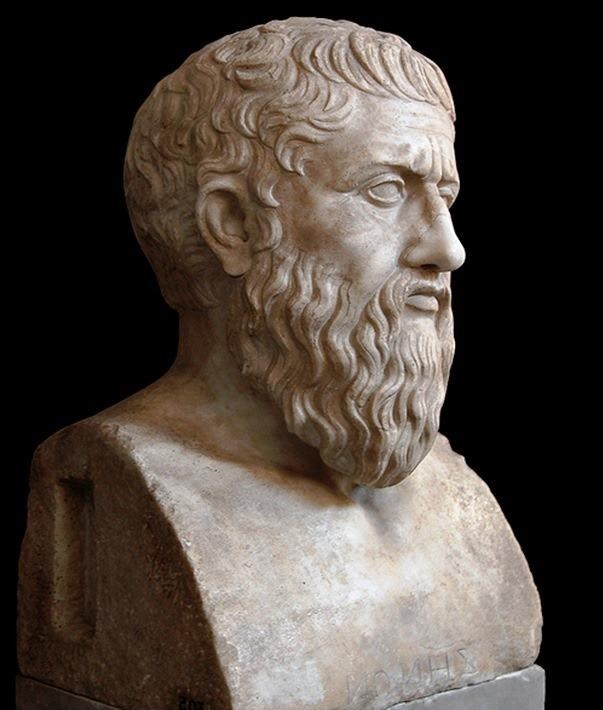

35. Plato. (Vatican. Rome.)

Of course, these portraits

are not done from the model, but still there is an attempt at a human

likeness — by which I do not mean to say that they are really like

the original.

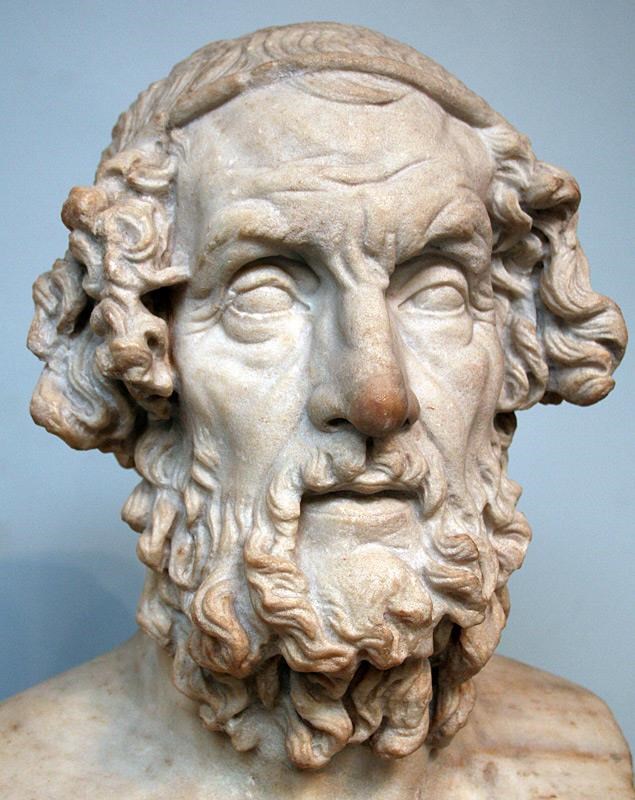

These remarks will refer

especially to the Homer which will now follow: —

36. Homer. (Museum. Naples.)

Now we gradually approach

the 2nd century.

37. The Victory of Samothrace. (Louvre. Paris.)

38. The Venus of Milo. (Louvre. Paris.)

This famous work does, indeed,

preserve the tradition of the Golden Age, although it belongs to a later

period.

In the next picture, on

the other hand, we see a fresh attempt to bring in movement: —

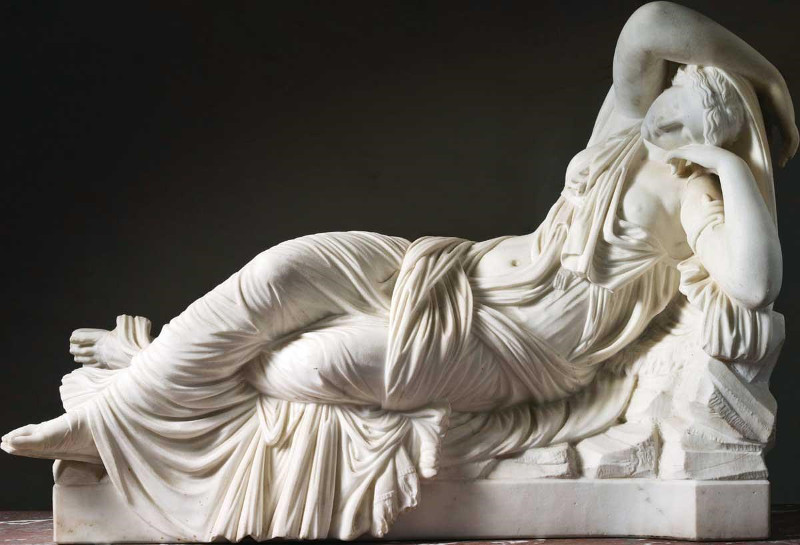

39. Sleeping Ariadne.

This is probably a work

of the same period, but you will see a distinct contrast between the

two.

And now we come towards

the last century before the birth of Christ. We come to the School of

Rhodes.

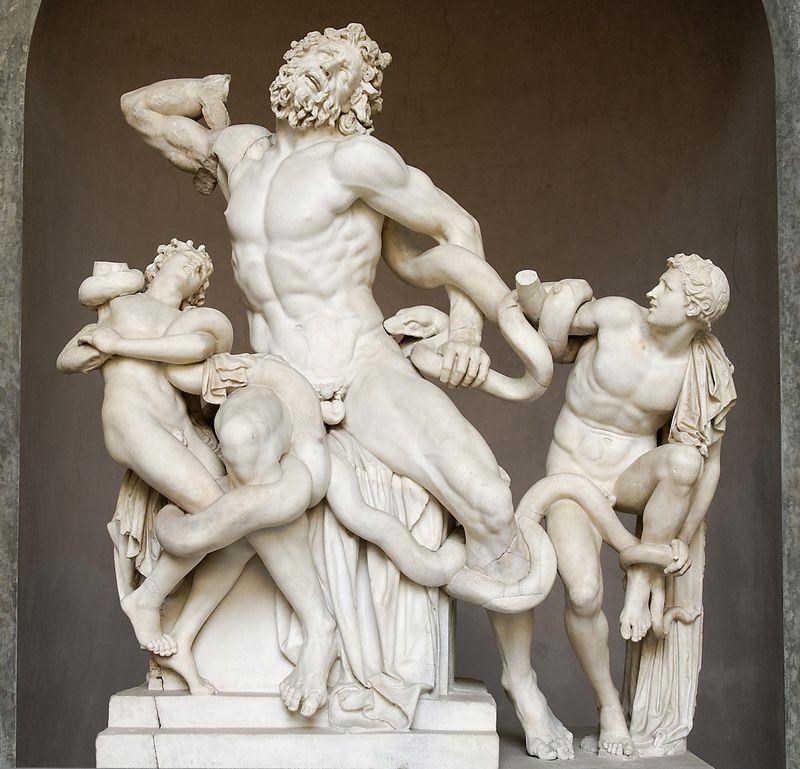

40. Laocoön. (Vatican. Rome.)

This is the famous

Laocoön group — the starting-point, as you know, of many an

artistic discussion, ever since Lessing's Laocoön of the 18th

century. It is the work of three sculptors of the School of Rhodes.

Lessing's writings on this subject are, indeed, most interesting. He

tried to show, you will remember, how the poet describes is not placed

before the eyes. We must call it to life in our imaginations. Whereas

what the plastic artist has created is there before our eyes. Therefore,

says Lessing, what the plastic artist portrays must contain far more

repose; it must represent moments which can at least be imagined —

for a single moment — in repose.

Much has been said and written

about this Laocoon group, especially in relation to Lessing's explanations.

It is interesting how the aestheticist, Robert Zimmermann, — without,

of course, having any knowledge of Spiritual Science — arrived at an

explanation which needs, no doubt, to be supplemented, but which was none

the less correct for an age that had not Spiritual Science. His explanation

contains — albeit only as an instinctive suggestion — some

element of what I have been setting forth today. We see the priest,

Laocoon, with his two sons, wound around by the serpents and going towards

their death. Now we cannot but be struck by the peculiar way in which

the body has been moulded. Much has been written on this subject. Robert

Zimmermann rightly pointed out: The whole representation is such that

we have before us the very moment where the life (or, as we should say,

the etheric body) is already fleeing away. It is already a moment of

unconsciousness. Hence the artist represents it as though the body of

Laocoon were already falling asunder. That is the marvellous quality

about this figure. The body is already being differentiated into its

parts. Thus even in this late product we see how the Greek was aware of

the etheric body. He brings to expression the actual moment where life is

passing into death. It is the quick withdrawal of the etheric body through

the shock — the shock that is expressed by the awful snakes

coiling around. This effect of the etheric body withdrawing from the

physical, and the physical falling asunder, is the characteristic thing

in the Laocoon; not the other things that are so often said, but the

peculiar way the body becomes differentiated. We could not imagine the

body thus, unless we conceived it as the moment when the etheric body

is drawing away.

And now two more examples

— imitations of earlier works, perhaps, which have, none the less,

made a great impression on later students of Art.

41. Apollo Belvedere. (Vatican. Rome.)

This is the famous Apollo

Belvedere — Apollo represented as a kind of battle-hero.

42. Artemis. (Louvre. Paris.)

This, too, will be a later

imitation of an earlier work.

Now, as we know, the Art

of the ancient Greece gradually drew near its decline, when Greece was

subjugated by Rome. In Rome, to begin with, there was a kind of imitation

of the Greek Art. It was carried across to Rome, but it was soon submerged

in the widespread unimaginativeness of the Roman people, to which we

have frequently referred.

The next centuries, as you

know ... were to a large extent a dark and troubled age for our evolution.

Then a new age began. I will only repeat quite briefly: — In the 12th

and 13th centuries in Italy, when through manifold circumstances they

rediscovered some of the ancient works of Art that had been buried in

the early Middle Ages, the contemplation of the ancient works kindled

the rise of a new Art, which grew in time into the Art of the Renaissance.

From the 13th century onwards, artists would educate themselves by means

of the Antique — the works of Art that had been found or excavated,

though the number at that time was relatively small.

We will now consider this

re-discovery of the ancient Art in the period immediately preceding the

Renaissance. In Niccola Pisano in the 13th century we find a wonderfully

refined spirit who waxed enthusiastic over the relics of Greek Art, and

tried to create once more in the spirit of the Greeks — out of his

own imagination fructified, as it were, by the Greek Art itself.

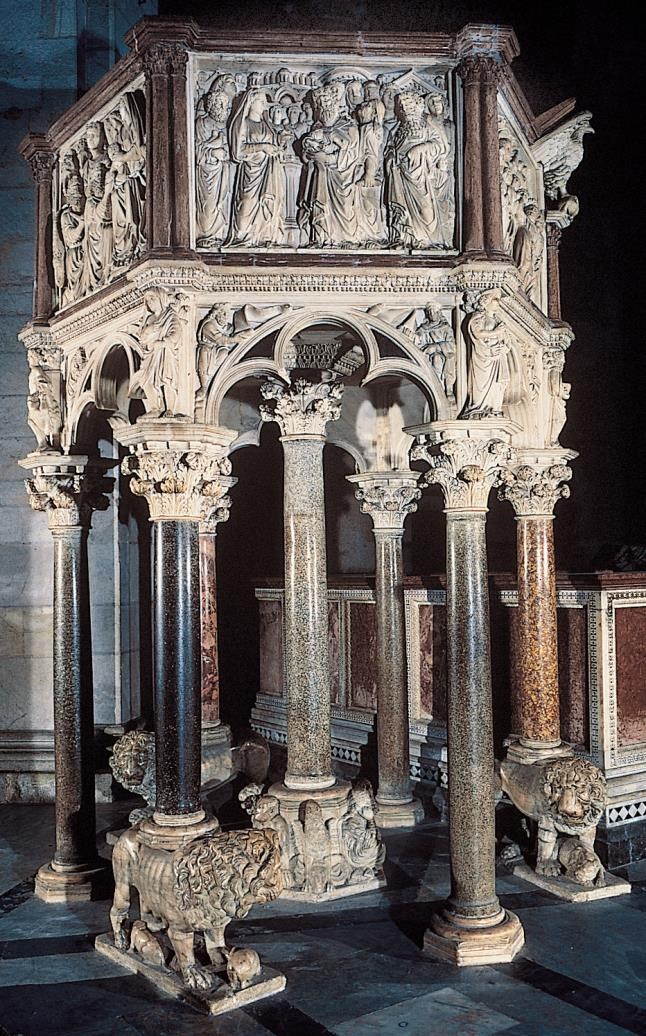

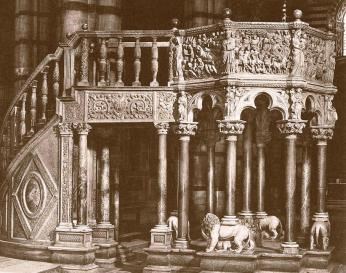

Our first picture is the

famous pulpit in the Baptistery at Pisa; note the reliefs in the upper

portion: —

43. Niccola Pisano. Pulpit in the Baptistery at Pisa.

The pulpit is supported

by antique columns between which are Gothic arches. Underneath are also

lion figures; above are the relief in which he expressed so wonderfully

what he owed to the inspiration of the antique. Niccola Pisano worked

until the end of the 13th century.

44. Niccola Pisano. Adoration by the Three Wise

Men. (Relief. Details of the above.)

Another representation of

the same subject: —

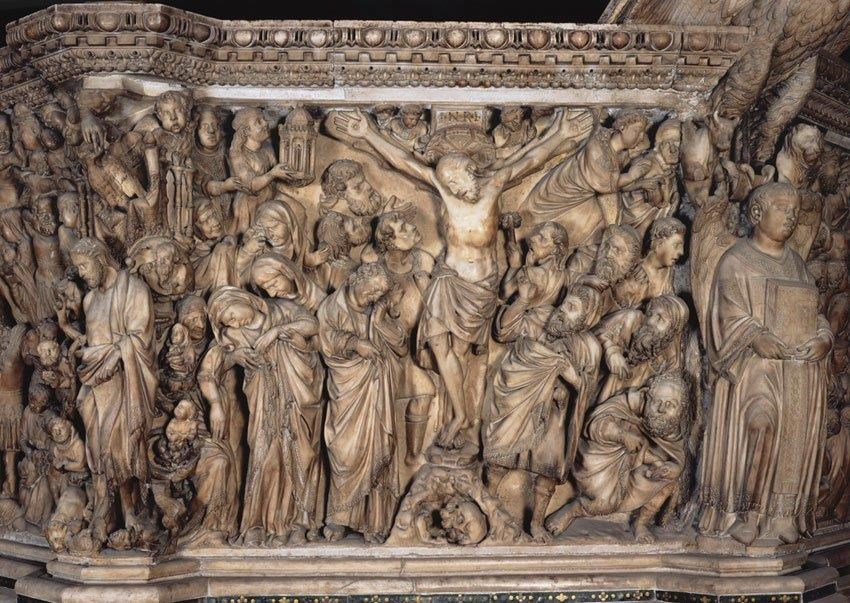

45. Niccola Pisano: The Crucifixtion. (Relief.

Pulpit in the Cathedral at Siena.)

We now go on to Giovanni

Pisano. In his works you will observe already a far greater element

of movement. A certain quietude pervades all the figures of Niccola

Pisano.

46. Giovanni Pisano. Pulpit. (San Andrea. Pistoja.)

47. Giovanni Pisano. Capital from the above Pulpit.

Truly, it was due to the

stimulus and inspiration of the Antique, arising, to begin with, in

the Pisanos, that the Christian Art afterwards became able to express

its motifs so perfectly as it did in

the Renaiscance.

48. Giovanni Pisano. Bas-Relief from the same Pulpit.

The next two are by Giovanni Pisano: —

49. Giovanni Pisano. Pulpit in the Cathedral at Pisa.

We see at the same time

how naturally the Antique grew together with the Gothic.

And two Madonnas from him:

51. Giovanni Pisano. Madonnas. (Berlin and

Padua.)

And now we have a sample

of the work of Andrea Pisano, who was summoned to do one of the Bronze

gates of the Baptistery at Florence.

52. Andrea Pisano. Tubal Cain. (Campanile.

Florence.)

A Bas-Relief representing

Tubal Cain, inventor of the craft of metallurgy according to the Bible,

the Old Testament.

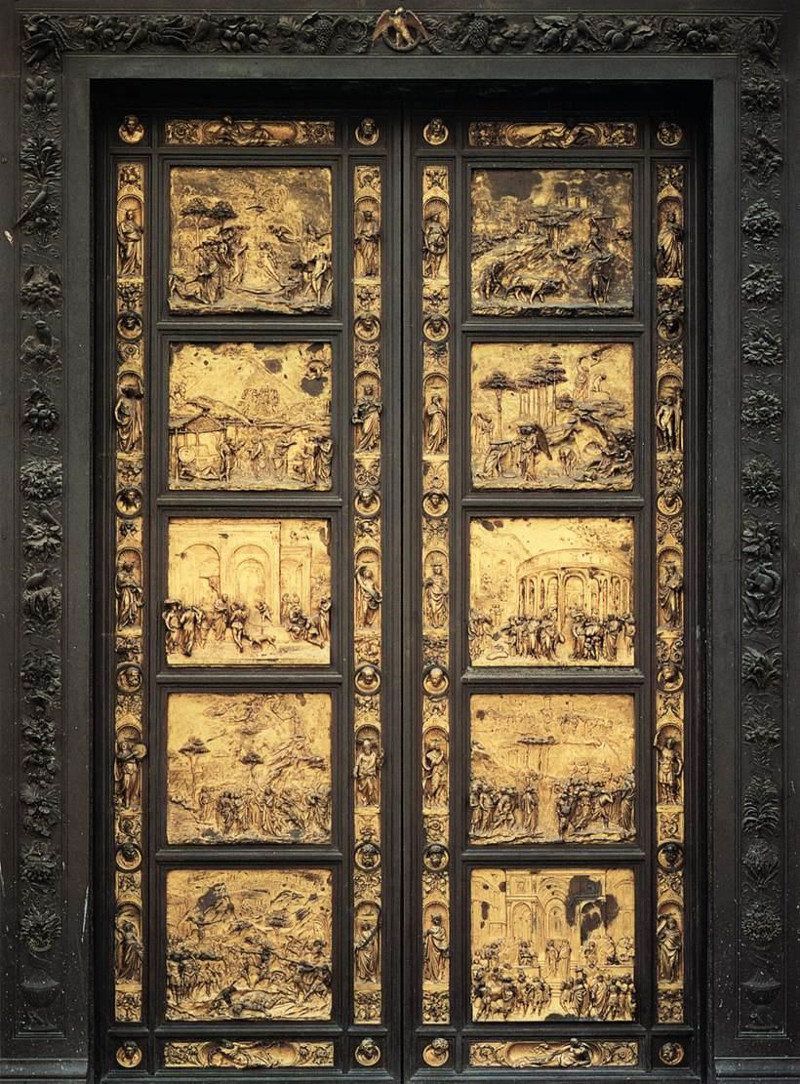

We have thus approached the

15th century, and we come to Ghiberti, the great artist who at the age of

twenty years was already able to compete with the others in designing

the doors of the Baptistery in Florence.

53a. Ghiberti. The Offering of Isaac. (Baptistry. Florence.)

53b. Ghiberti. Northern Door of the Baptistery in Florence.

At the early age of twenty he

was already allowed to do the Northern Portals. From a simple goldsmith's

apprentice he grew to be one of the very greatest artists. These

bas-reliefs of the doors of the Baptistery in Florence are, of their kind,

among the greatest things in the whole evolution of Art. Afterwards the

Eastern door was also given to him to do. It represents scenes from the

Old Testament. Michelangelo said that these were worthy to be the gates

of Paradise.

[Note: the doors at the

Florence Baptistery were moved causing some confusion as to where the

works of Ghiberti and Andrea Pisano are located. – e.Ed.]

54. Ghiberti. The Gates of Paradise. (Baptistery. Florence.)

This work had, indeed, a

great influence on the whole Art of Michelangelo himself. Even in the

details we can recognise certain motifs in Michelangelo's paintings,

which he took from these bronze reliefs.

55a. Ghiberti. Sacrifice of Isaac. (Detail from the 'Gates

of Paradise.')

55b. Ghiberti. Creation of Man. (Detail from the 'Gates

of Paradise.')

56. Ghiberti. St. Stephen

These works of Ghiberti's

were undoubtedly due to a faithful contemplation of the Antique.

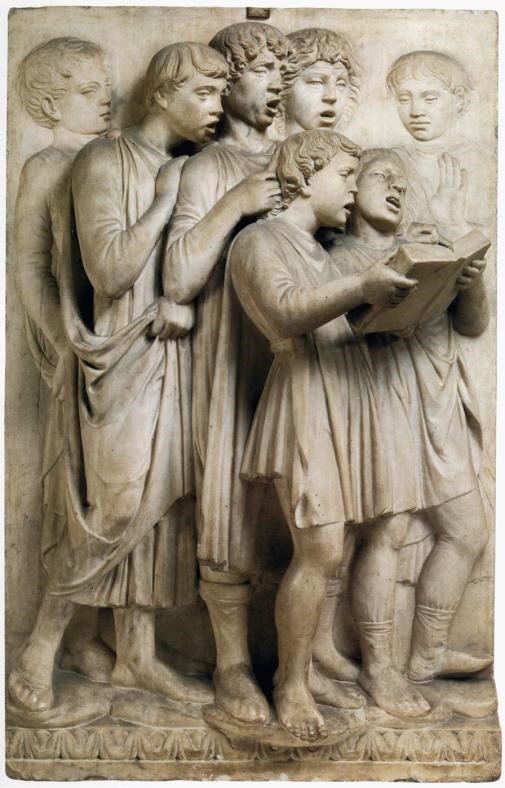

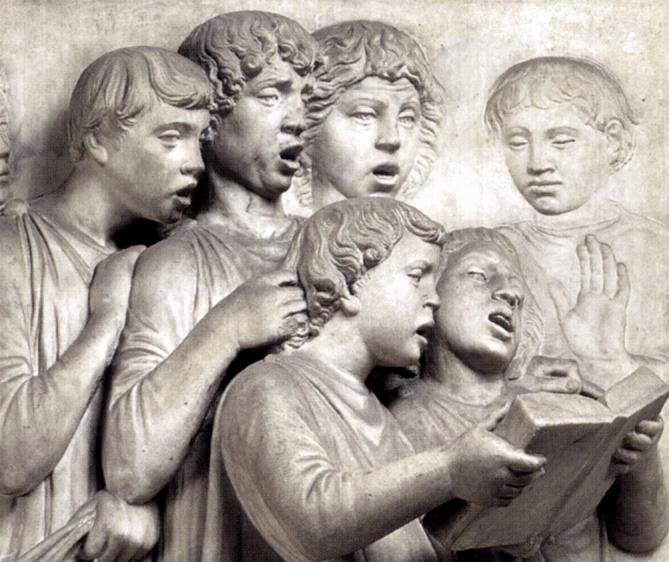

We will now insert the Art

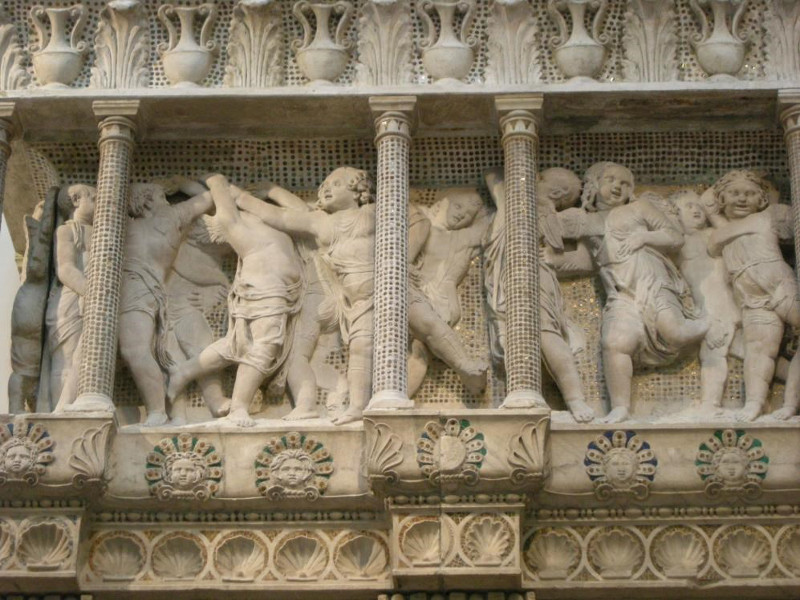

of the della Robbias. To begin with: —

57. Luca della Robbia. Dancing Boys. (Cathedral. Florence.)

The della Robbias are famous

as the inventors of a special art — the use of burnt clay as a

material. To a large extent their works were done in this material.

58. Luca della Robbia. Singing Boys. (Cathedral. Florence.)

Luca della Robbia covers

practically the whole period of the 15th century.

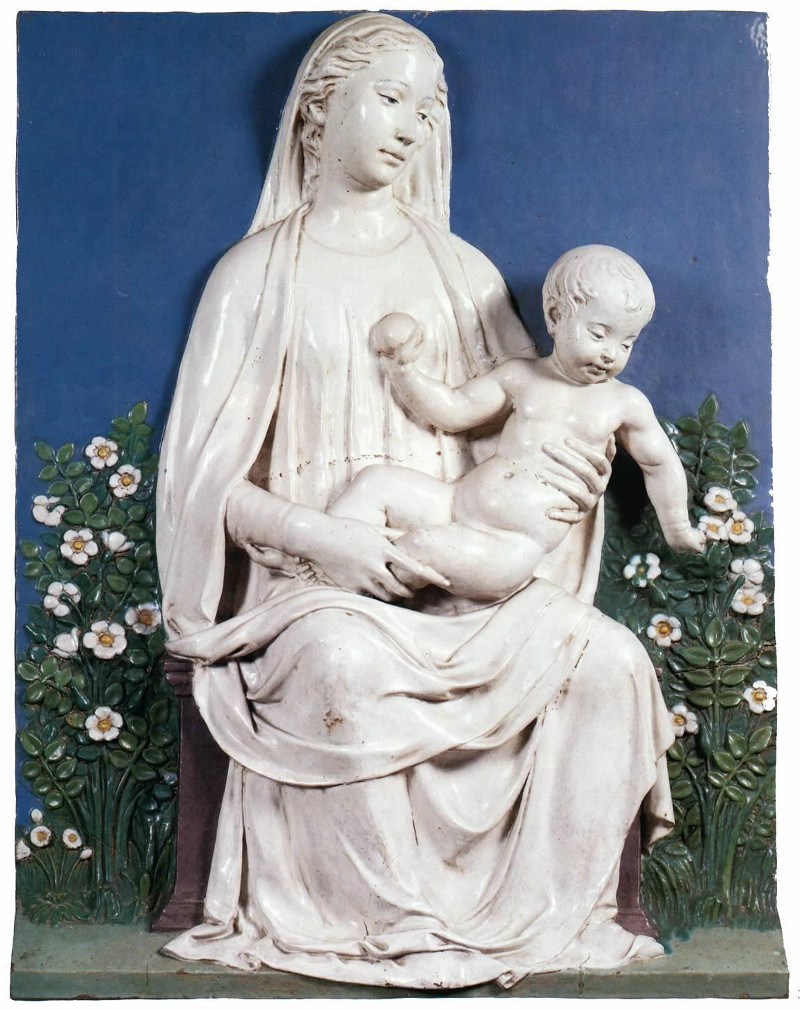

59. Luca della Robbia. Madonna in the Bower of Roses.

(Museo Nazionale. Florence. )

Observe once more the age

that we have now come into. The Art of antiquity that had been derived

from immediate inner experience — experience of the Etheric —

works as a great stimulus and inspiration. Yet at the same time the Art of

this age is founded on what is seen — the faithful representation of

what is actually seen. It is no longer based on something felt and sensed

inwardly. It is very interesting to receive the impression of the two

epochs, one after the other, in this way.

60. Andrea della Robbia. Bambino. (Spedale degli Innocenti. Florence.)

61. Madonna (della Cintola Fojano). Andrea della Robbia.

The Madonna is shown in

the spiritual world.

62. Giovanni della Robbia. Reception of the Pilgrims

and Washing of the Feet. (Hospital. Pistoja.)

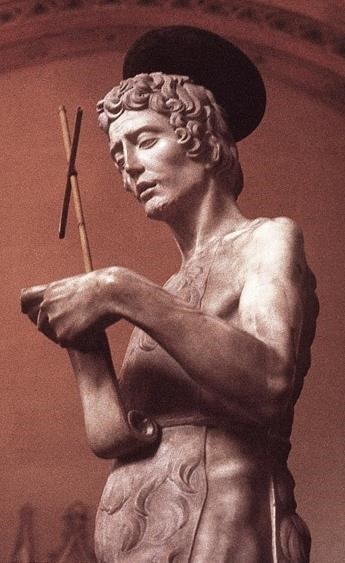

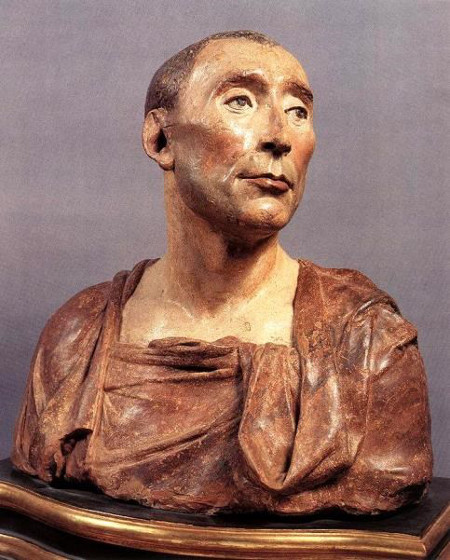

We now go on to Donatello,

who was born in 1386. In him we observe the influence of the Antique

combined already with a decided tendency to Naturalism. His vision has

a naturalistic stamp. Donatello enters lovingly and sympathetically into

Nature. But while he becomes a real naturalist, he derived his technique

from what his predecessors had evolved out of the old tradition.

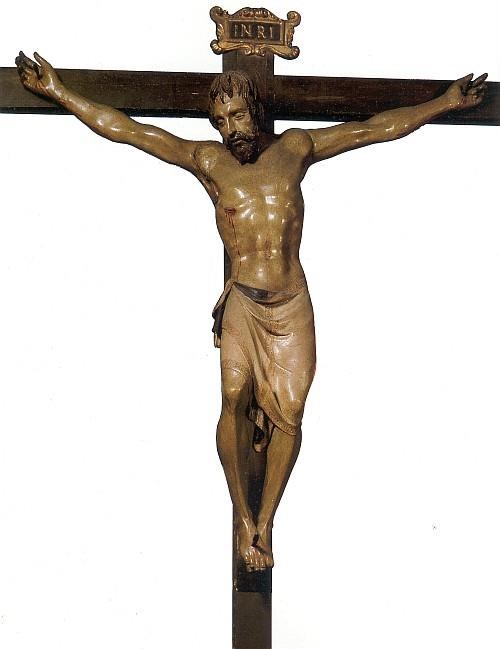

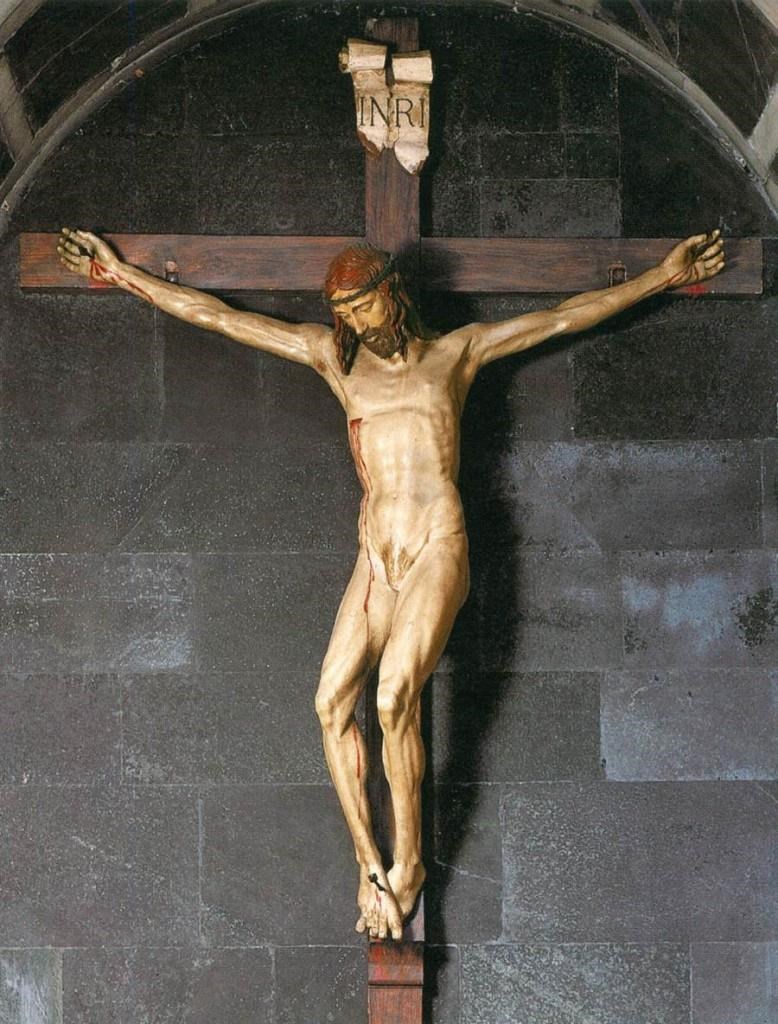

His naturalism went so far

that his friend and companion in his strivings, Brunelleschi, seeing

a Christ that Donatello attempted, exclaimed; “That is not a Christ

that you are doing, that is a peasant:” Donatello at first did not

understand what he meant. The anecdote is interesting, if not historically

true; it gives us a right impression of the relation between the two

artists — the contrast between the two artists — the contrast

between Donatello and Brunelleschi with his high idealism — immersed

as he was in the contemplation of the Antique, in its rebirth. Brunelleschi

thereupon himself undertook to model the Christ. Donatello — for

they lived together — had gone out to buy things for their breakfast.

He returned with all the dainties for their common meal wrapped up in a

kind of pinafore. Just as he entered, Brunelleschi unveiled his Christ.

Donatello gaped with wide open mouth, and his astonishment was such

that he dropped all the breakfast on the ground. What Brunelleschi had

achieved was a revelation to him. We cannot say that the impression he

experienced went very deep. None the less, Brunelleschi undoubtedly had an

ennobling influence on him. The above story goes on to relate, Donatello

was so overwhelmed that he even imagined the breakfast had disappeared.

“What have we now to eat?” he said. “We'll just pick the

things up again,” said Brunelleschi. “I see I shall never be

able to do any more than peasants,” said Donatello.

Donatello. Crucifix. (Florence.)

Filippo Brunellesco. Crucifix. (Florence.)

Donatello. David. (Florence.)

And now we come to the beautifully self-contained marble

statues by Donatello in Florence, showing his ability — out of

his naturalistic vision — to create human figures strong and firm,

even as he wanted them, their feet firmly planted on the ground.

63. Donatello. David. (Museo Nazionale, Florence.)

66. Donatello. Jeremiah. (Campanile. Florence.)

Habbakuk

65. Donatello. St. Peter. (Or San Michele. Florence.)

67. Donatello. St. John Baptist. (Campanile. Florence.)

In Donatello Naturalism

certainly finds its way in. It is not the inner soul that we found in

the Northern sculpture, but a decidedly naturalistic vision of what

the outer senses see.

69. Donatello. Habakkuk. (Campanile. Florence.)

Niccola Pisano and Donatello were two artists who powerfully

influenced Michelangelo. Those who afterwards saw what Michelangelo

created — especially in his early period — remembered Donatello

and coined the phrase which then became current: Donatello Michelangelosed

or Michelangelo Donatelloised.

70. Donatello. Lodovico III Gonzaga

71. Donatello. St. George. (Florence.)

Most characteristic is this

St. George by Donatello. All the power of his naturalism is in it. Such

works of Art arose out of the freedom of the free city of Florence,

which also gave birth to Michelangelo.

By a wider historic necessity

— a cosmopolitan historic necessity, we might say, — it

was in Italy that the Antique came to life again. On the other hand,

the naturalistic tendency everywhere was bound up with the mood and

feeling that arose in the culture of the Free Towns or Cities. Here,

as in the North — though in different ways, of course, according

to the different characters of the people, — we find this element

arising out of the life of the free cities, where man became conscious

of his dignity, his freedom, his individual being. In the characteristic

works of Art which we found in the Netherlands and other Northern parts,

we were reminded again and again of the life of the free cities and the

feeling that pervaded them. And so it is here, when we look at this figure

of a man, so firmly established in the world of space, this Florentine

St. George. We cannot but think of the civilisation of the Free Cities,

whose atmosphere made such a thing possible.

72. Donatello. Bas-Relief. St. George and the Dragon.

(From the Base of the St. George Statue.)

73. Donatello. Madonna Pazzi. (Berlin.)

74. Donatello. Bas-Relief. Angels Singing. (Uffizi.

Florence.)

75. Donatello. Annunciation. (Santa Croce. Florence.)

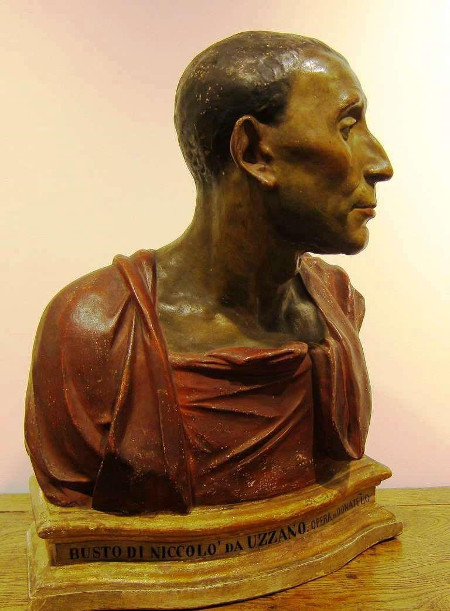

76. Donatello, Portrait of Niccolo da Uzzano.

Donatello. Gattamelata.

Donatello. Gattamelata.

Finally, we will show some

examples of Verrocchio — teacher of Leonardo and Perugino — in

his capacity as a sculptor. First the famous equestrian statue: —

77. Verrocchio. Bertolomeo Colleoni. (Venice.)

79. Verrocchio. Head and Shoulders. (Detail of the above.)

80. Verrocchio. Guiliano de Medici. (Paris.)

And in conclusion: —

81. Verrocchio. David. (Museo Nazionale. Florence.)

And so, my dear friends,

we have had before us the artists of the pre-Renaissance. They entered

deeply into the Antique and brought it forth again, in a time when men

no longer lived within the soul in the same inward way as did the ancients.

They brought to life again in outer vision, contemplation, what the

ancients had felt and known inwardly — what they had feelingly known,

knowingly felt, I should say. Moreover, they united this with the element

which had to come in the 5th Post-Atlantean epoch — the element of

naturalism, with clear outward vision. They thus became the fore-runners of

the great artists of the Renaissance — of Leonardo, of Michelangelo,

and, through Perugino, of Raphael himself. For all these were influenced

directly by the Art of the precursors, whose works we have seen today.

They stood, undoubtedly, on the shoulders of these artists of the pre-

Renaissance period, the early Renaissance.

It is interesting to see,

in relation to this figure, for example, how quickly they progressed

in that time. Compare this David with the David by Michelangelo. Here

you still see a comparative inability to dramatise the theme —

to take hold of it in movement. Michelangelo, on the other hand, in

his David, has seized the very essence of dramatic movement; he has

caught the actual moment of resolve to go out against Goliath.

82. Michelangelo. David, Marble Statue

(Florence, Academy)

Thus we have tried to bring

these things to some extent before our souls: — On the one hand what

radiates from the Greek Art itself, and on the other, its lighting-up-again

in the age when Humanity was trying to find the life of Art once more

with the help of the Greek Art which came to life again.

|