Yesterday we discussed the nature of will in so far as will is

embodied in the human organ. Today we will use this knowledge of man's

relationship to will to fructify our consideration of the rest of the

human being.

You will have noticed that in treating of the human being up to now I

have chiefly drawn attention to the intellectual activity, the

activity of cognition, on the one hand, and the activity of will on

the other hand. I have shown you how the activity of cognition has a

close connection with the nerve nature of the human being, and how the

activity of will has a close connection with the activity of the

blood. If you think this over you will also want to know what can be

said with regard to the third soul power, that is, the activity of

feeling. We have not yet given this much consideration, but today, by

thinking more of the activity of feeling, we shall have the

opportunity of entering more intensively into an understanding of the

two other sides of human nature, namely cognition and will.

Now there is one thing that we must be clear about, and this I have

already mentioned in various connections. We cannot put the soul

powers pedantically side by side, separate from each other, thus:

thinking, feeling, willing, because in the living soul, in its

entirety, one activity is always merging into another.

Consider the will on the one hand. You will realise that you cannot

bring your will to bear on anything that you do not represent to

yourself as mental picture, that you do not permeate with the activity

of cognition. Try in self-contemplation, even superficially, to

concentrate on your willing, you will find that in every act of will

the mental picture is present in some form. You could not be a human

being at all if mental picturing were not involved in your acts

of will. And your willing would proceed from a dull instinctive

activity, if you did not permeate the action which springs forth from

the will with the activity of thought, of mental picturing.

Just as thought is present in every act of will, so will is to be

found in all thinking. Again, even a purely superficial contemplation

of your own self will show you that in thinking you always let your

will stream into the formation of your thoughts. In the forming of

your own thoughts, in the uniting of one thought with another, or

passing over to judgments and conclusions — in all this there

streams a delicate current of will.

Thus actually we can only say that will activity is chiefly will

activity and has an undercurrent of thought within it; and thought

activity is chiefly thought activity and has an undercurrent of will.

Thus, in considering the separate faculties of soul, it is impossible

to place them side-by-side in a pedantic way, because one flows into

the other.

Now this flowing into one another of the soul activities, which is

recognisable in the soul, is also to be seen in the body, where the

soul activity comes to expression. For instance, let us look at the

human eye. If we look at it in its totality we shall see that the

nerves are continued right into the eye itself; but so also are the

blood vessels. The presence of the nerves enables the activity of

thought and cognition to stream into the eye of the human being; and

the presence of the blood vessels enables the will activity to stream

in. So also in the body as a whole, right into the periphery of the

sense activities, the elements of will on the one hand and thought or

cognition on the other hand are bound up with each other. This applies

to all the senses and moreover it applies to the limbs, which serve

the will: the element of cognition enters into our willing and into

our movements through the nerves, and the element of will enters in

through the blood vessels.

But now we must also learn the special nature of the activities of

cognition. We have already spoken of this, but we must be fully

conscious of the whole complex belonging to this side of human

activity, to thought and cognition. As we have already said, in

cognition, in mental picturing lives antipathy. However strange it may

seem, everything connected with mental picturing, with thought, is

permeated with antipathy. You will probably say, “Yes, but when I

look at something I am not exercising any antipathy in this

looking.” But indeed you do exercise it. When you look at an

object, you exercise antipathy. If nerve activity alone were present

in your eye, everything you looked at would be an object of disgust to

you, would be absolutely antipathetic to you. But the will, which is

made up of sympathy, also pours its activity into the eye, that is,

the blood in its physical form penetrates into the eye, and it is only

by this means that the feeling of antipathy in sense-perception is

overcome in your consciousness, and the objective, neutral act of

sight is brought about by the balance between sympathy and antipathy.

It is brought about by the fact that sympathy and antipathy balance

one another, and by the fact also that we are quite unconscious of

this interplay between sympathy and antipathy.

If you take Goethe's Theory of Colour, to which I have already

referred in this connection, and study especially the

physiological-didactic part of it, you will see that it is because

Goethe goes more deeply into the activity of sight that there

immediately enters into his consideration of the finer shades of

colour the elements of sympathy and antipathy. As soon as you begin to

enter into the activity of a sense organ you discover the elements of

sympathy and antipathy which arise in that activity. Thus in the sense

activity itself the antipathetic element comes from the actual

cognitive part, from mental picturing, the nerve part — and the

sympathetic element comes from the will part, from the blood.

As I have often pointed out in general anthroposophical lectures there

is a very important difference between animals and man with regard to

the constitution of the eye. It is a significant characteristic of the

animal that it has much more blood activity in its eye than the human

being. In certain animals you will even find organs which are given up

to this blood activity, as for example the ensiform cartilage, or the

“fan.” From this you can deduce that the animal sends much

more blood activity into the eye than the human being, and this is

also the case with the other senses. That is to say, in his senses the

animal develops much more sympathy, instinctive sympathy with his

environment than the human being does. The human being has in reality

more antipathy to his environment than the animal only this antipathy

does not come into consciousness in ordinary life. It only comes into

consciousness when our perception of the external world is intensified

to a degree of impression to which we react with disgust. This is only

a heightened impression of all sense-perceptions; you react with

disgust to the external impression. When you go to a place that has a

bad smell and you feel disgust within the range of this smell, then

this feeling of disgust is nothing more than an intensification of

what takes place in every sense activity, only that the disgust which

accompanies the feeling in the sense impression remains as a rule

below the threshold of consciousness. But if we human beings had no

more antipathy to our environment than the animal, we should not

separate ourselves off so markedly from our environment as we actually

do. The animal has much more sympathy with his environment, and has

therefore grown together with it much more, and hence he is much more

dependent on climate, seasons, etc., than the human being is. It is

because man has much more antipathy to his environment than the animal

has that he is a personality. We have our separate consciousness of

personality because the antipathy which lies below the threshold of

consciousness enables us to separate ourselves from our environment.

Now this brings us to something which plays an important part in our

comprehension of man. We have seen how in the activity of thought

there flow together thinking (nerve activity as expressed in terms of

the body) and willing (blood activity as expressed in terms of the

body). But in the same way there flow together in actions of will the

real will activity and the activity of thought. When we will to do

something, we always develop sympathy for what we wish to do. But it

would get no further than an instinctive willing unless we could bring

antipathy also into willing, and thus separate ourselves as

personalities from the action which we intend to perform. But the

sympathy for what we plan to do is predominant, and a balance is only

effected by the fact that we bring in antipathy also. Hence it comes

about that the sympathy as such lies below the threshold of

consciousness, and part of it only enters consciously into that which

is willed. In all the numerous actions that we perform not merely out

of our reason but with real enthusiasm, and with love and devotion,

sympathy predominates so strongly in the will that it penetrates into

the consciousness above the threshold, and our willing itself appears

charged with sympathy, whereas as a rule it merely unites us with our

environment in an objective way. Just as it is only in exceptional

circumstances that our antipathy to the environment may become

conscious in cognition, so our sympathy with the environment (which is

always present) may only become conscious in exceptional

circumstances, namely, when we act with enthusiasm and loving

devotion. Otherwise we should perform all our actions instinctively.

We should never be able to relate ourselves properly to the objective

demands of the world, for example in social life. We must permeate our

will with thinking, so that this will may make us members of all

humanity and partakers in the world's process itself.

Perhaps it will be clear to you what really happens if you think what

chaos there would be in the human soul if we were perpetually

conscious of all this that I have spoken of. For if this were the case

man would be conscious of a considerable amount of antipathy

accompanying all his actions. This would be terrible! Man would then

pass through the world feeling himself continually in an atmosphere of

antipathy. It is wisely ordered that this antipathy as a force is

indeed essential to our actions, but that we should not be aware of

it, that it should lie below the threshold of consciousness.

Now in this connection we touch upon a wonderful mystery of human

nature, a mystery which can be felt by any person of perception, but

which the teacher and educator must bring to full consciousness. In

early childhood we act more or less out of pure sympathy, however

strange this may seem; all a child does, all its romping and play, it

does out of sympathy with the deed, with the romping. When sympathy is

born in the world it is strong love, strong willing. But it cannot

remain in this condition, it must be permeated with thought, by idea,

it must be continuously illumined as it were by the conscious mental

picture. This takes place in a comprehensive way if we bring ideals,

moral ideals, into our mere instincts. And now you will understand

better the true significance of antipathy in this connection. If the

impulses that we notice in the little child were throughout our life

to remain only sympathetic, as they are sympathetic in childhood, we

should develop in an animal way under the influence of our instincts.

These instincts must become antipathetic to us; we must pour antipathy

into them. When we pour antipathy into them we do it by means of our

moral ideals, to which the instincts are antipathetic, and which for

our life between birth and death bring antipathy into the childlike

sympathy of instincts. For this reason moral development is always

somewhat ascetic. But this asceticism must be rightly understood. It

always betokens an exercise in the combating of the animal element.

This can show us to what a great extent willing in man's practical

activity is not merely willing but is also permeated with idea, with

the activity of cognition, of mental picturing.

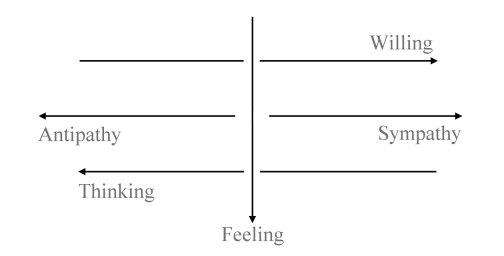

Now between cognition or thinking on the one hand and willing on the

other hand we find the human activity of feeling. If you picture to

yourselves what I have now put forward as willing and as thinking, you

can say: From a certain central boundary there stream forth on the one

hand all that is sympathy, willing, and on the other hand all that is

antipathy, thinking. But the sympathy of willing also works back into

thinking, and the antipathy of thinking works over into willing. Thus

man is a unity because what is developed principally on the one side

plays over into the other. Now between the two, between thinking and

willing, there lies feeling, and this feeling is related to thinking

on the one hand and to willing on the other hand. In the soul as a

whole you cannot keep thought and will strictly apart, and still less

can you keep the thought and will elements apart in feeling. In

feeling, the will and thought elements are very strongly intermingled.

Here again you can convince yourselves of the truth of these remarks

by even the most superficial self-examination. What I have already

said will lead you to this conviction, for I told you that willing,

which in ordinary life proceeds in an objective way, can be

intensified to an activity done out of enthusiasm and love. Then you

will clearly see willing as permeated with feeling — that willing

which otherwise springs forth from the necessities of external life.

When you do something which is filled with love or enthusiasm, that

action flows out of a willing which you have allowed to become

permeated by a subjective feeling. But if you examine the sense

activities closely — with the help of Goethe's theory of colour

— you will see how these are also permeated by feeling. And if

the sense activity is enhanced to a condition of disgust, or on the

other hand to the point of drinking in the pleasant scent of a flower,

then you have the feeling activity flowing over directly into the

activity of the senses.

But feeling also flows over into thought. There was once a philosophic

dispute which — at all events externally — was of great

significance — there have indeed been many such in the history of

philosophy — between the psychologist Franz Brentano and the

logician Sigwart, in Heidelberg. These two gentlemen were arguing

about what it is that is present in man's power of judgment. Sigwart

said: “When a man forms a judgment, and says, for example,

‘Man should be good’; then feeling always has a voice in a

judgment of this kind; decision concerns feeling.” But Brentano

said, “Judgment and feeling (which latter consists of emotions)

are so different that the faculty of judgment could not be understood

at all if one imagined that feeling played into it.” He meant

that in this case something subjective would play into judgment, which

ought to be purely objective.

Anyone who has a real understanding for these things will see from a

dispute of this kind that neither the psychologists nor the logicians

have discovered the real facts of the case, namely that the soul

activities are always flowing into one another. Now consider what it

is that should really be observed here. On the one hand we have

judgment, which must of course form an opinion upon something quite

objective. The fact that man should be good must not be dependent on

our subjective feeling. The content of the judgment must be objective.

But when we form a judgment something else comes into consideration

which is of a different character. Those things which are objectively

correct are not on that account consciously present in our souls. We

must first receive them consciously into our soul. And we cannot

consciously receive any judgment into our soul without the

co-operation of feeling. Therefore, we must say that Brentano and

Sigwart should have joined forces and said: True, the objective

content of the judgment remains firmly fixed outside the realm of

feeling, but in order that the subjective human soul may become

convinced of the rightness of the judgment, feeling must develop.

From this you will see how difficult it is to get any kind of exact

concepts in the inaccurate state of philosophic study which prevails

to day. One must rise to a different level before one can reach such

exact concepts, and there is no education in exact concepts to-day

except by way of spiritual science. External science imagines that it

has exact concepts, and rejects what anthroposophical spiritual

science has to give, because it has no conception that the concepts

arrived at by spiritual science are by comparison more exact and

definite than those commonly in use to-day, since they are derived

from reality and not from a mere playing with words.

When you thus trace the element of feeling on the one hand in

cognition, in mental picturing, and on the other hand in willing, then

you will say: feeling stands as a soul activity midway between

cognition and willing, and radiates its nature out in both directions.

Feeling is cognition which has not yet come fully into being, and it

is also will which has not yet fully come into being; it is cognition

in reserve, and will in reserve. Hence feeling also, is composed of

sympathy and antipathy, which — as you have seen — are only

present in a hidden form both in thinking and in willing. Both

sympathy and antipathy are present in cognition and in will, in the

working together of nerves and blood in the body, but they are present

in a hidden form. In feeling they become manifest.

Now what do the manifestations of feeling in the body look like? You

will find places all over the human body where the blood vessels touch

the nerves in some way. Now wherever blood vessels and nerves make

contact feeling arises. But in certain places, e.g., in the senses,

the nerves and the blood are so refined that we no longer perceive the

feeling. There is a fine undercurrent of feeling in all our seeing and

hearing, but we do not notice it, and the more the sense organ is

separated from the rest of the body, the less do we notice it. In

looking, in the eye's activity, we hardly notice the feelings of

sympathy and antipathy because the eye, embedded in its bony hollow,

is almost completely separated from the rest of the organism. And the

nerves which extend into the eye are of a very delicate nature and so

are the blood vessels which enter into the eye. The sense of feeling

in the eye is very strongly suppressed.

In the sense of hearing it is less suppressed. Hearing has much more

of an organic connection with the activity of the whole organism than

sight has. There are numerous organs within the ear which are quite

different from those of the eye, and the ear is thus in many ways a

true picture of what is at work in the whole organism. Therefore the

sense activity which goes on in the ear is very closely accompanied by

feeling. And here even people who are good judges of what they hear

find it difficult to discriminate clearly — especially in the

artistic sphere — between what is purely thought-element and what

is really feeling. This fact explains a very interesting historical

phenomenon of recent times, one which has even influenced actual

artistic production.

You all know the figure of Beckmesser in Richard Wagner's

“Meistersinger.” What is Beckmesser really supposed to

represent? He is supposed to represent a musical connoisseur who quite

forgets how the feeling element in the whole human being works into

the thought element in the activity of hearing. Wagner, who

represented his own conceptions in Walther, was, quite one-sidedly,

permeated with the idea that it is chiefly the feeling element that

should dwell in music. In the contrast between Walther and Beckmesser,

arising out of a mistaken conception — I mean mistaken on both

sides — we see the antithesis of the right conception, viz. that

feeling and thinking work together in the hearing of music. And this

came to be expressed in a historical phenomenon, because as soon as

Wagnerian art appeared, or became at all well known, it found an

opponent in the person of Eduard Hanslick of Vienna, who looked upon

the whole appeal to feeling in Wagner's art as unmusical. There are

few works on art which are so interesting from a psychological point

of view as the work of Eduard Hanslick On Beauty in Music. The

chief thought in this book is that whoever would derive everything in

music from a feeling element is no true musician, and has no real

understanding for music: for a true musician sees the real essence of

what is musical only in the objective joining of one tone with

another, and in Arabesque which builds itself up from tone to tone,

abstaining from all feeling. In this book, On Beauty in Music

Hanslick then works out with wonderful purity his claim that the

highest type of music must consist solely in the tone-picture, the

tone Arabesque. He pours unmitigated scorn upon the idea which is

really the very essence of Wagnerism, namely that tunes should be

created out of the element of feeling. The very fact that such a

dispute as this between Hanslick and Wagner could arise in the sphere

of music is a clear sign that recent psychological ideas about the

activities of the soul have been completely confused, otherwise this

one-sided idea of Hanslick's could never have arisen. But if we

recognise the one-sidedness and then devote ourselves to the study of

Hanslick's ideas which have a certain philosophical strength in them,

we shall come to the conclusion that the little book On Beauty in

Music is very brilliant.

From this you will see that, regarding the human being for the moment

as feeling being, some senses bear more, some less of this whole human

being into the periphery of the body, in consciousness.

Now in your task of gaining educational insight it behoves you to

consider something which is bringing chaos into the scientific

thinking of the present day. Had I not given you these talks as a

preparation for the practical reforms you will have to undertake, then

you would have had to plan your educational work for yourselves from

the pedagogical theories of to-day, from the existing psychologies and

systems of logic and from the educational practice of the present

time. You would have had to carry into your schoolwork the customary

thoughts of the present day. But these thoughts are in a very bad

state even with regard to psychology. In every psychology you find a

so-called theory of the senses. In investigating the basis of

sense-activity the psychologist simply lumps together the activity of

the eye, the ear, the nose, etc., all in one great abstraction as

“sense-activity.” This is a very grave mistake, a serious

error. For if you take only those senses which are known to the

psychologist or physiologist of to-day and consider them in their

bodily aspect alone, you will notice that the sense of the eye is

quite different from the sense of the ear. Eye and ear are two quite

different organisms — not to speak of the organisation of the

sense of touch which has not been investigated at all as yet, not even

in the gratifying manner in which eye and ear have been investigated.

But let us keep to the consideration of the eye and ear. They perform

two quite different activities so that to class seeing and hearing

together as “general sense-activity” is merely “grey

theory.” The right way to set to work here would be to speak from

a concrete point of view only of the activity of the eye, the

activity of the ear, the activity of the organ of smell, etc. Then we

should find such a great difference between them that we should lose

all desire to put forward a general physiology of the senses as the

psychologies of to-day have done.

In studying the human soul we only gain true insight if we remain

within the sphere which I have endeavoured to outline in my

Truth and Science,

and also in

The Philosophy of Freedom.

Here we can speak of the soul as a single entity without falling into

abstractions. For here we stand upon a sure foundation; we proceed

from the point of view that man lives his way into the world, and does

not at first possess the whole of reality. You can study this in

Truth and Science,

and in

The Philosophy of Freedom.

To begin with man has not the whole reality; he has first to develop

himself further, and in this further development what formerly was not

yet reality becomes true reality for him through the interplay of

thinking and perception. Man first has to win reality. In this

connection Kantianism, which has eaten its way into everything, has

wrought the most terrible havoc. What does Kantianism do? First of all

it says dogmatically: we look out upon the world that is round about

us, and within us there lives only the mirrored image of this world.

And so it comes to all its other deductions. Kant himself is not clear

as to what is in the environment which man perceives. For reality is

not within the environment, nor is it in phenomena: only gradually,

through our own winning of it, does reality come in sight, and the

first sight of reality is the last thing we get. Strictly speaking,

true reality would be what man sees in the moment when he can no

longer express himself, the moment in which he passes through the

gateway of death.

Many false elements have entered into our civilisation, and these work

at their deepest in the sphere of education. Therefore we must strive

to put true conceptions in the place of the false. Then, also, shall

we be able to do what we have to do for our teaching in the right way.

|