|

LECTURE II

Dornach, 30th April 1922

I

spoke yesterday about the sense organs and drew attention

to the way they appear when, to our ordinary knowledge, we add

what is gained through knowledge of supersensible worlds.

Taking the lungs as an example I showed that the moment we rise

with spiritual sight into supersensible worlds, then other

organs become just as much sense organs as our present ones. We

come to the conclusion that our organs are in process of

evolution and transformation. This is not apparent to ordinary

consciousness because we are always observing a process

arrested, a process which, because we cannot survey either its

earlier or its later stages, reveals only a momentary stage of

its evolution.

If

our advance into the imaginative world — as I termed it in

the book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its

Attainment — reveals the lung in a state of

transition, from being a vital organ to becoming a sense organ,

we can no longer regard it in the way we do in ordinary life.

We realize that what we ordinarily observe is a momentarily

arrested stage in the lungs' evolution. If we compare this with

the arrested stage of the evolution of the eyes, we come to the

conclusion that the lung reveals itself to be at a younger

stage than the eye.

I

said yesterday that we could at least put forward as a question

whether the eye, in the course of evolution, had once been a

vital organ as the lung is now. Let us remain cautious and

merely say that there is at least a possibility that the

relationship between lung and eye is like that of a child to a

grown-up. One shows itself to be a younger entity, the other an

older one. In other words, the eye in its

youth could at some stage of world evolution have been a vital

organ which has now become a sense organ, while the lung, which

is now a vital organ, could later become a sense organ. Yet we

shall only come to know the truth by advancing further in

supersensible knowledge. To do so let us today consider

the other extreme of the soul's life, the pole of the will.

Yesterday it was described purely externally.

| |

Diagram 1

Click image for large view | |

Concerning the pole of the will we can ask: How does it appear

when we have attained imaginative cognition? We find that the

organs belonging to the will sphere become paler. They fade

away before spiritual sight. Our limbs are organs that belong

more immediately to the will sphere; they grow paler. In fact,

the characteristic feature, when we rise to imaginative

consciousness and observe the external organism, is that the

limbs become lost. And so does the metabolic system with which

the limbs are connected. This aspect of man is simply no longer

there in the intensity it was to physical sight. When we

compare all that, which to higher vision fades from view, with

something in the physical world, we arrive at a quite

astonishing result.

| |

Diagram25

Click image for large view | |

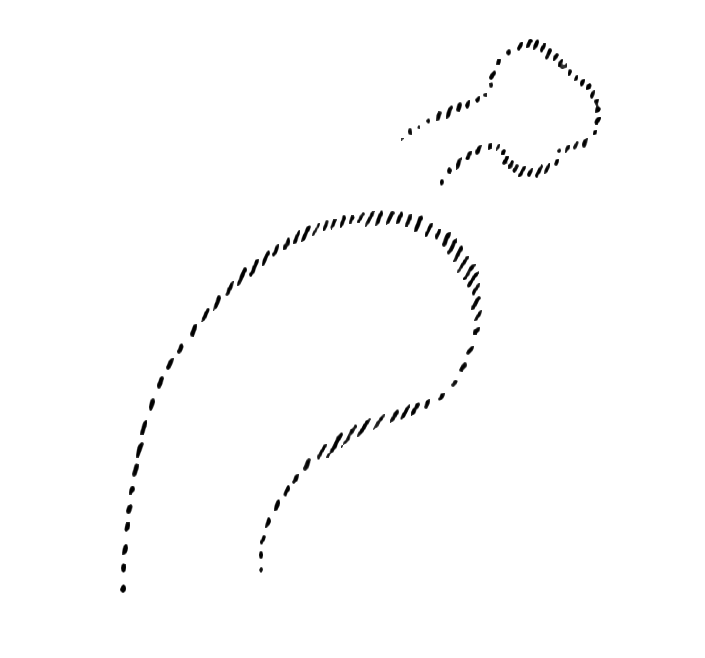

Let

me draw some sketches of what comes about. Imagine that

this is man as he appears to physical sight (drawing on the

left). Now we observe him with imaginative cognition: the limbs

grow paler (drawing in the center). Suppose this next sketch is

of all that which becomes ever paler and fades away. What we

get becomes more and more like an image of a human corpse

(drawing on the right). In other words, we get an image of what

man leaves behind at death, of that which is either buried or

cremated. When a corpse is cremated it ceases to be

visible to physical sight, just as that part of man ceases to

be visible to supersensible consciousness.

But

something else becomes visible: At the place where the arms

fade away something becomes visible which a former

instinctive clairvoyance saw more or less correctly. It was

said that where physical man has arms spiritual beings have

wings; and that after death so did spiritual man. However, to

replace spiritual beings with a kind of symbol in the form of a

winged creature, a superior bird, is a crude ghostlike

image. When cognition of higher worlds is further developed,

that is when one ascends, in the way I have described, from

imaginative knowledge to inspired knowledge, then one

recognizes what one is really seeing. And to depict this as

wings is a distortion, but then it is not so easy to recognize

the reality. However, the moment the ascent is made from

imagination to inspiration then, by careful observation, one

gradually realizes what takes the place of say the right arm

and hand. Let me put it this way: You will agree that we make a

lot of movements with our arms. According to

materialistic critics a dreadful lot of movement is carried out

in eurythmy. People who do not understand eurythmy cannot bear

it. But when you observe, with inspired cognition, what

is done by the movements in eurythmy, you no longer see the

arms and hands, all you see are their movements. All the

individual movements are all there, and because they all merge

into one another they look like wings.

Well, people who are not eurythmists also move their arms. In

fact, most of the movements done by human beings are done

with the arms. All the movements, their curves and forms become

visible (see drawing, orange). Everything

physical — muscles, flesh, bones — ceases to be

visible, whereas all movements become visible. And it is the

same with the legs. I said yesterday that the movements man

makes are not confined within the body. In order to point to

something useful I spoke of chopping wood rather than of sport.

When someone chops wood, he makes continuous movements.

All these are also visible when one ascends from imagination to

inspiration. However, man causes things to happen not only

through his body, he does so also by means of thoughts, perhaps

through other people. All the events that he causes to take

place gradually become visible, particularly as one ascends

from inspiration to intuition. In short, when we contemplate

the pole of will, all that at death is placed in the grave

ceases to be visible; whereas all man's deeds gradually become

visible. After a person's death what is still in existence are

all the deeds he has carried out. That has further

life and continues to exist. What passes through the gate of

death can be said to be a birth of will. So you see as regards

the limbs we must choose a different approach in order to

find the transition from the physical aspect of man to the

soul. And the same applies to the metabolic system.

| |

Diagram 3

Click image for large view | |

We have now considered from a certain aspect the nature of

man's senses and also what so to speak constitutes his will

nature — that is, the source of his actions. To enable us

to proceed further let us return to the pole of the senses. Let

us look back with imaginative and inspired consciousness and

see what becomes of a sense organ, let us say the eye, and then

consider it at the stage where the lung let us say has become

an organ of perception.

When the lung has become an organ of perception we begin to see

a completely different world. Even in public lectures I have

often spoken about the fact that another world becomes

perceptible to the higher man who gradually develops and frees

himself from ordinary man, though the latter is still present

and in control. We also begin to experience the world

more rhythmically, more musically as soon as the lung becomes

sense organ. In fact, we begin to experience all that

which in my book Theosophy I described partly as Soul

World, partly as Spirit Land. When the lung becomes sense organ

we experience a different environment. I mentioned

yesterday that the lungs become sense organ in their etheric

part. But what happens to our ordinary sense organs?

Unlike the organs of the metabolic-limb system which disappear

to higher vision, the sense organs do not disappear, they

reveal themselves as they are at present but in their spiritual

nature. They reveal themselves as objective entities; they

become, as it were, spiritual beings. They are — if I may

so express it — what peoples our spirit world. One gets the

strong impression that the sense organs expand into worlds. We

witness, as it were, a world being built up out of our sense

organs. Our soul has the experience that the world which we now

witness coming into being unites itself with something else. It

unites with what in ordinary life we look upon as our memories;

that is, our mental pictures of past events.

Here I must point to an important experience which occurs

as one ascends from imaginative to inspired knowledge.

The sense organs become, as it were, independent beings which

take into themselves our memories. As we turn our attention to

this fact we become clearly aware of a certain aspect of our

soul's nature.

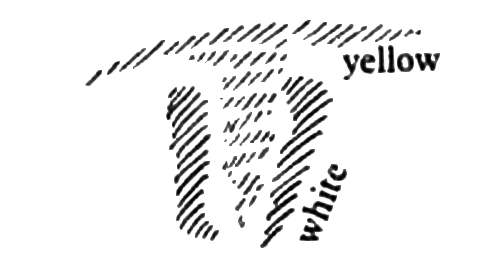

Take the example of the human eye. To ordinary

consciousness this organ is as I described it yesterday.

When we begin to develop imaginative cognition and then ascend

to inspired cognition, the physical aspect of the eye

disappears but not the eye itself. It becomes ever more

spiritual and expands to cosmic proportions. It becomes a

world, a world that unites itself with our memories; it unites

with the thoughts that live in our memory (yellow in diagram).

Along this path we gradually attain a specific insight into a

certain area.

A

trivial concept of popular psychology is the idea that man

perceives with his physical organs and develops his mental

pictures — i.e., his thoughts — from the physical

percepts. And then the thoughts he has formed go — well,

they go somewhere. The philosophy of Herbart,

[

Johan

Friedrich Herbart, 1776-1841. Philosopher and Educator.

]

in particular, attained eminence by letting thoughts

disappear beneath some sort of threshold. Then when they were

remembered they wandered up again and appeared in

consciousness.

This idea always reminds me of a children's game I often

watched as a small boy: One runs both hands up a child's arm,

tickling him while chanting, “Up comes a little mouse who

wants to hide in Joey's house.” This suggests to the

child that a mouse is running up his arm to hide in a box

somewhere inside his head. Psychology is just about as

clever; it also lets thoughts emerge from sense

perceptions and then walk into a sort of savings-box within the

soul from where they arise again when remembered. It is a

trivial concept but one that is much bandied about in

psychology. The true facts become clear only when one comes to

know the whole process through imaginative and inspired

knowledge. What then becomes clear is the following: Things we

see through our eyes are there, they are not created by the

eyes. So, too, what we see through imagination and inspiration

is also there, it is not created by the higher faculties.

In

other words, while ordinary consciousness is functioning

the higher reality is also present. It all goes on but becomes

visible only to supersensible sight. It goes on through every

moment of our waking life. This reveals that whenever we

perceive in ordinary consciousness, another process takes place

beyond that consciousness. Another process goes on which runs

parallel to that of perception, only we do not become aware of

it until we have attained higher consciousness. Let me put it

this way: In ordinary life whatever we perceive in everyday

consciousness is already there. But all that which only becomes

visible to imagination and inspiration is also there. A process

takes place of which we know nothing in ordinary consciousness.

When we learn to know it through higher cognition we become

aware that the memory pictures we have in ordinary

consciousness are indeed only pictures. Their true reality

becomes apparent to higher consciousness. There is no question

of memory pictures wandering up again after having first

gone down somewhere.

| |

Diagram 4

Click image for large view | |

When I form a mental picture of a physical object and then

withdraw from it, the mental picture remains. After a while the

mental picture disappears and because it is mere picture it

disappears completely. But our senses do something

else: they carry out a process we do not see. They

vitalize in our inner being a process that is living, which

endows the thoughts contained in our memory with reality.

This means that when we have a physical perception and form a

mental picture (red) then another process (blue) takes place

through which something real comes about — i.e., a

reality, not just a picture. The picture vanishes, but when we

remember then this, real memory takes the place of the former

physical percept and what we now perceive is the reality that

was brought to life in us, without our knowledge, at the time

of the physical perception. And this reality is the soul.

If

today you have physically before you a human being and you see

him again after eight or ten years then nothing of what you see

today will be present. You cut your nails, your skin flakes

off, externally the physical body continually falls away;

it becomes dust. After seven to ten years that which today is

the physical substance most deeply embedded in you will have

come so far to the surface that it flakes off or is cut off as

long nails. You can be certain that what is today at the center

of your physical body gradually comes to the surface and falls

away. But then what remains? What remains of man's whole

being is solely the reality developed inwardly through

the process taking place parallel to that of forming mental

pictures.

In

ten years' time nothing of what you are today will exist

except the memories of your experiences. Today nothing exists

of what you were ten years ago except what your memories have

made of you. You are woven out of your memories, all that is

physical flakes off and disappears. Anyone with sound common

sense, who thinks through and correlates what he can observe in

ordinary consciousness, will acknowledge the truth of what I

have brought before you with the help of imagination and

inspiration.

If

we would picture to ourselves how a human being develops,

taking into account his soul nature, then from one

aspect — and I beg you to keep in mind that we are

considering everything from one pole, the pole of

thought — we would depict it thus (see drawing). When we

are born, a body is provided for us (white lines). This body is

gradually filled with all that results from the process taking

place parallel to sense perception (yellow lines). All that

which is body (white lines) gradually flakes off. We eat, we

take in a variety of substances from the air. All this reaches

into the process taking place when memories are formed

and builds up the bodily nature ever anew, whereas that which

impregnates the soul from the metabolic system is what is

buried after death. The soul itself weaves its own essential

being. It develops its being from those processes which

to begin with are experienced merely as mental pictures.

One can say in truth: I live in thoughts, but what I experience

as thought in ordinary consciousness is only image. It is, so

to speak, an attendant phenomenon to the reality which I bring

into existence.

| |

Diagram 5

Click image for large view | |

Something of extraordinary significance emerges from this: it

shows that what takes place within us, unknown to ordinary

consciousness, is by far the most important for man's

development. We look at the world, what we perceive

through our various senses brings us experiences; we rejoice in

what meets our eyes or ears. And all the time while we see,

hear and feel there slips into our inner being all that which

later can be called up in memory. In other words, all that

constitutes my soul slips into me. That is an activity that

goes on perpetually. One can never say that it is

because it is forever surging and weaving.

Whoever earnestly endeavors to ascend to spiritual knowledge

will have vivid experiences of all I have indicated.

Whatever one has accumulated in life by way of written

notes can, like any possession, be comfortably taken home. And

because in present day life comfort is much preferred to

inner experiences of disquiet, all knowledge tends to be given

a form that allows it to be written down and comfortably taken

home. It is said, however, that anthroposophical lectures do

not transcribe well, so one actually does not get much from

what is written down about them and comfortably taken home.

But, you see, that is only a reflection of the experience of

higher knowledge. When a university student today

prepares for an examination he is really happy when he

manages to store up some facts in his head. And when

after three or four weeks the time comes for the examination he

hopes to be able to pour it all out unchanged just as he

crammed it in. One cannot set about acquiring higher knowledge

in that way. Those who really develop higher knowledge are

faced with spiritual perceptions that have a life of their own.

Higher knowledge is perpetually alive. It will not permit

itself to be so conveniently stored in notebooks as do

the rigid concepts which today are kept as scientific records

of the external world. These, though radically expressed, are

real inner facts.

Take the case of someone who has attained supersensible

cognition to a fairly high degree. Let us say he has at present

certain spiritual perceptions; he can attain those experiences

again later by means I have often described. He may

experience them after three or four years; they have

meanwhile gone through a life of their own. If he once more

builds them up they burden his soul with uncertainty. One

gradually learns that this is nothing exceptional.

Supersensible knowledge in general, fills one with uncertainty

when it develops further — when, as it were, it grows old.

One has to attain certainty about it all over again. One

experiences uncertainty already the following day even about

the loftiest spiritual perceptions and must struggle to attain

the knowledge once more. Only lower kinds of perceptions

cease to be alive, and they become specters which reappear

unchanged. The one who has them feels satisfied that he has

attained some insight into a higher world. He grabs a notebook

to make sure the experience is preserved. He would in fact like

to have a kind of soul-notebook for the purpose.

Genuine spiritual perceptions act differently — they are

living entities and must continually be created anew. One must

go through the process repeatedly for already the

following day uncertainty arises, especially about the

loftiest experiences, and one must win certainty all over

again. One must relate to spiritual knowledge as one relates in

the physical world to what is reality and not image. A real

process in the physical world is the need to eat: not

many of you would refrain from eating today because you had a

good meal a week ago. You would not say that the meal of a week

ago is still in you nourishing you, so that there is no need to

eat today. By contrast a soul content arrived at via the body

remains and can be recalled unchanged in many respects. That is

not the case with a spiritual soul content; this does not just

fade; its very certainty is repeatedly shaken and must be

regained ever again.

One

effect of this aspect of attaining supersensible

cognition is that the world is, as it were, illumined by

it. It is like coming into a brightly lit cosmic hall. After

eight days one has the following experience: A certain residue

of memory lingers due to the fact that in attaining this higher

knowledge one drew near its reality and this had an

effect even on one's physical being. But concerning the

supersensible perceptions as such, one has the experience

that one continuously meets them in a dark room where one

must rekindle the light ever again. This is an indication of

how supersensible knowledge is experienced in the human

soul.

When supersensible perceptions are attained then, unlike

the instinctive clairvoyant, one cannot claim that they remain

like specters. The spiritual realm that is attained must be

conquered anew. Yet, though the experiences do not stay in

ordinary memory, the effect naturally does. The effect is felt

after a time particularly if the supersensible knowledge has to

be faced again in the form of a written manuscript or

even — dreadful thought — in print. The spiritual

investigator may have before him a new edition of a book he has

written. He is faced with the external effect of his earlier

experiences.

I

can imagine there are lecturers who experience deep inner

satisfaction when they have before them the result of the

golden words they have spun together, especially if, again and

again, new editions are produced based on those same golden

words. It is a very pleasurable feeling. But the written

results originating from spiritual perceptions do not provide

pleasurable feelings; they cause pain. What has become

preserved and poured out into the physical world is a source of

pain. That is the other side of the coin. This pain is not only

like going with one's spiritual perceptions into a dark room

where one must kindle the light ever anew. It is like going

into a room where arrows are hurled at one from all sides. An

armor must be created against what one meets as a residue, as

an embodied remnant of supersensible worlds.

This is an indication of how soul life is experienced when one

has reached higher knowledge. In ordinary consciousness

one does not experience the soul's life directly; it is

adjusted to the physical body and experienced through it.

To experience the soul directly is different. The soul is

continuously becoming; it is in a state of transformation

and metamorphosis. This fact escapes one unless, during

supersensible experience, one enters into the process and

identifies with it. Yet, to do so is felt to be unbearable; it

causes pain because it is bound up with the past. Whenever a

spiritual experience is not of the present it causes pain and

one must be armed against this pain. So you see, if the living

content of higher knowledge has really been absorbed it is not

so easy to live with as that to which our students listen in

the universities. That knowledge only hurts when it has been

forgotten and the students do badly in examinations,

although that kind of knowledge does not in itself cause

pain, but pleasure, for when the students possess it they

rejoice. The knowledge may pain them later if they come to see

that there is something better than their own knowledge which

has become like fixed ideas in them.

When the supersensible is entered into deeply one

experiences it as, through and through, alive. One learns

how to attain and how to endure it. In the knowledge itself one

finds joy and satisfaction and also pain. One also learns at

last to know the soul directly in its reality. In ordinary

daily life the soul has fallen so deeply into materialism that

its life appears to consist merely of pale concepts. Into these

pale concepts warmth of feeling must be poured to rescue the

soul life from the painful, pale, cold thoughts which are but

images without life, whereas what is attained as

supersensible knowledge is alive; it is in fact the

living soul. And this living soul content gives us the first

real concept of what we are; for our memory pictures are but

faint reflections of the reality. If we manage to penetrate the

curtain of memories, we arrive at that which I have just

described as joyful, satisfying, light-filled and also

painful experiences of the world. In its participation in this,

our soul is united with a knowledge which itself contains

soul-life. The past we experience as pain, but we become aware

that what we experience as happiness and delight goes with us

through the portal of death; it is the future.

There must flow into ordinary powers of comprehension a

reflection, but a living one, of what I have been saying. If

mankind's past evolution is contemplated merely in the light of

the frigid ideas of history it remains just image, an image

which has significance only as long as it remains in our head.

Just as the mental pictures we form of sense perceptions

have significance only as long as we have them in our heads,

so, too, the mental pictures of history formed purely

intellectually have significance only for the head. What in

popular terms is called “the spirit of the times”

is in fact the historian's own spirit held up to reflect the

times.

One

only learns real history when one participates with living

knowledge in the reality of world evolution and mankind's

evolution, when one feels the greatest intensity of pleasure

and pain in the events taking place in the world. This means,

for example, to turn the eye of the soul backwards in

time to, let us say, ancient Persia, India or Greece; or any

other past age. When, for instance, one feels how

differently the Greeks experienced their tragedies from

the way modern man experiences a theater performance. Goethe

pointed to the fundamental difference between Greek

tragedies and modern dramas when he said that a modern

drama is a shadowy affair, whereas a Greek tragedy was a

world-shaking event. And certainly those who experienced

a Greek tragedy were affected by it very differently from the

way modern man is affected. The latter goes to the theater to

be amused and lets the play flow over him indifferently. When a

Greek watched a tragedy, he felt shaken through and through; he

felt shattered right down into his bodily nature. The basic

issues he saw portrayed sent a chill down his spine. The Greeks

also experienced life as full of sin and guilt and therefore

full of sickness. They felt the tragedy as a healing force.

They felt that a remedy was needed and that the public

performances repeatedly raised life out of its state of guilt

and sickness to what it truly ought to be. Thus, the

Greek tragedy was not something that merely provided amusement,

it constituted a power that acted as healing for what, in

social life, continuously fell into sickness.

What effect has modern drama on present-day society? Its effect

might be compared with that of having one's hair shampooed by

the hairdresser, whereas the effect of a Greek tragedy must be

compared with one's soul and body being healed by a truly

competent physician who with genuine health-giving medicine

dynamically vitalizes the organism through and through. When

one approaches history, identifying oneself completely

with every situation such as the one of a Greek watching a

tragedy, then history is indeed experienced very

differently from the usual way where there is no

participation.

In

the present-day world there is also social sickness, but no

remedy is sought as was done in ancient Greece. If one really

transfers one's soul into the Greek age in the anthroposophical

sense then — if I may express myself somewhat

trivially — one at last catches hold of the soul element

which nowadays is otherwise suppressed in ordinary

consciousness. In contemplating the world, one discovers

the soul.

This is what I wanted to describe to you in order to

demonstrate that if the soul is to be known in its reality one

must first find where it is hidden. The images produced in

ordinary consciousness tell one nothing of the soul.

However, these images are what psychologists describe as

soul. If one opens a book on modern psychology one finds the

first chapter dealing with mental pictures but described in the

way they appear in ordinary consciousness. What

psychologists describe is that which at every moment

dissolves (see drawing, red, page 24). Nothing is said about

the parallel process taking place beneath it. This approach of

modern psychology could be compared with a conference in which

instead of the chief speakers being present only their

portraits were there. The portraits would have the same

relation to the living reality they depict as man's

mental life has to reality in ordinary consciousness.

Psychologists are dealing with nothing but pictures; what

matters is the reality behind them.

I

have been at pains to show you the reality that lies

behind mental pictures. One cannot reach the soul through

ordinary consciousness. It must first be drawn up from

hidden depths. That must be kept in mind; to do so is

very important when one speaks about the human soul in

relation to world evolution. As the soul's true being is

attained, so one gradually enters into world evolution.

In

these first two lectures I have attempted to show how, through

spiritual knowledge, one can reach the soul. Now that a

foundation has been laid we shall consider, in the further

lectures, human soul life and its connection with world

evolution in a more accessible form.

|