|

LECTURE III

Dornach, 5th May 1922

In

order to extend our considerations and link on to what was said

last week, let us bring to mind some of the things already

known to us. When we consider man as he lives between

birth and death we see his life divided into sections which can

be studied from various aspects. Attention has often been drawn

to the alternating states of waking and sleeping and we know

that dreaming is a state between these two. Thus, we have three

states of consciousness in ordinary life — waking, dreaming

and sleeping. Human nature itself can be divided

correspondingly. When we trace the content of ordinary

consciousness we experience thinking — i.e., forming mental

pictures. I have often pointed out that only in this state, or

to the extent that we are in this state, are we really awake.

Anyone who observes himself without prejudice will

acknowledge that feeling presents a much duller state of

consciousness than thinking. Feelings surge through the soul

and, unlike mental pictures, we cannot relate them so

definitely either to something in the external world or to

something remembered. And we are conscious, or at least could

become conscious, that as soon as we are awake, feelings come

and go very much the way dreams come and go in the intermediate

state between waking and sleeping. Anyone who has a sense

for comparing different states of consciousness must say to

himself: Dreams have a pictorial quality; feelings are

more like indefinite forces surging within us. But apart from

their content, dreams come and go just as feelings come and go.

Furthermore, dreams emerge from a general darkness and dullness

of consciousness just as feelings emerge and again

submerge within a general inner existence.

When we consider the will we find that what takes place within

us when we have a will impulse remains as unknown to us as that

which we sleep through. The only aspect that is clear in a will

impulse is the thought that initiated it. What next comes into

consciousness is the movement of our limbs or the event taking

place in the external world through our will. But what takes

place in the legs when walking or in the arms when we lift them

remains as unconscious as that which takes place between

falling asleep and waking. So we can say that while we are

awake we experience all three conditions of waking,

dreaming and sleeping.

However, we shall only arrive at a comprehensive

knowledge of man if we use discernment when comparing

what is given us, on the one hand, as sleeping, dreaming and

waking; and, on the other, as willing, feeling and thinking.

Let us consider sleeping man, on the one hand, and, on the

other, man engaged in an act of will. The characteristic

feature of sleeping man is that the very factor that makes us

human — the experience of the I or ego — is absent.

This situation is usually described by saying that the I,

between falling asleep and waking up, is outside of what is

present before us as physical man.

Let

us now compare dreaming man with man experiencing feelings. By

means of ordinary self-observation you will immediately

recognize that dream pictures come before the soul in a, so to

speak, neutral fashion. When we dream, either on waking or

before falling asleep, we cannot really say that the pictures

come before the soul like a tapestry, rather do they surge and

weave within the soul. Thus, what then takes place in the soul

differs from what occurs when fully awake. When awake we know

that we take hold of the pictures which we then have; we grasp

them in our inner being. They are not so nebulous and

indefinite as dreams.

Let

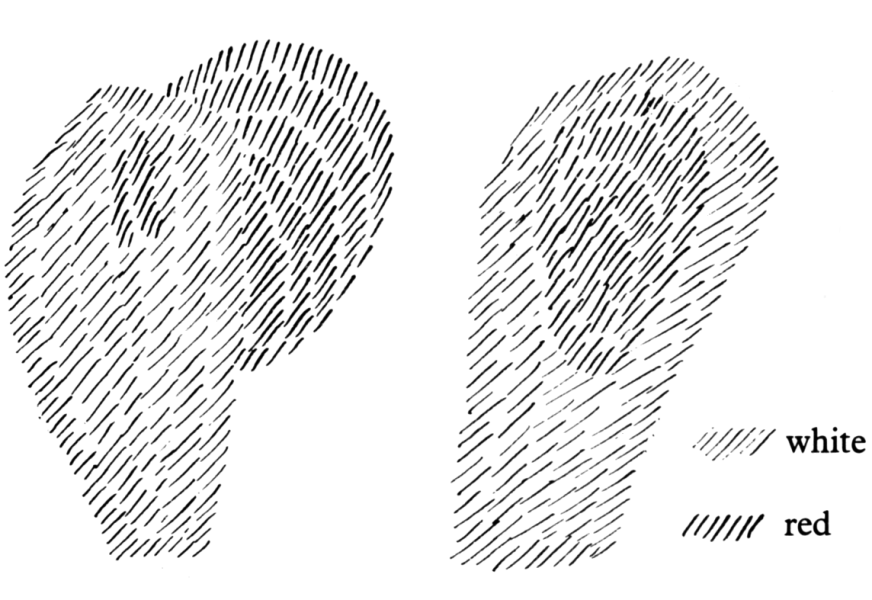

me illustrate what has just been described (left hand drawing).

Let us imagine man schematically (white lines) and draw what we

imagine to be weaving dreams (red lines). One must imagine the

red part as a tissue of dreams experienced by the soul

which continually withdraws and again approaches the soul.

| |

Diagram 1

Click image for large view | |

The

moment he wakes up man does not experience such a tissue of

weaving pictures. He now has the pictures of whatever he is

experiencing firmly within him (right hand drawing). The

weaving pictures which were formerly outside are now

within him; he lays hold of them with his body and because he

does so they are no longer undefined weaving pictures but

something which he controls inwardly.

When man is fully awake then what weaves and hovers as dreams

become thoughts within him. He is then in control of what

now lives in his soul as mental pictures. In this relationship

you can see that the soul is taking hold of something

which from outside draws into man. What has just been described

is in fact the entry of what we call the astral body into man's

inner being. To ordinary consciousness it is that which before

entry weaves and hovers as dreams. The astral body is,

therefore, within us when after waking we begin to think. We

then form mental pictures and we know that we do so, for these

mental pictures are under our control. As long as they

are dreams they hover outside. You need only imagine a kind of

cloud that hovers near you in which dreams are weaving. You

then draw in this cloud, you now control it from within.

Because it is no longer outside you cease to dream. Just

as you grasp objects with your hands so do you grasp dreams

with your inner being; which means that you have drawn in the

astral body.

We

must ask: What precisely is it that we now have within

us? We can perhaps find a point of reference by looking at

certain dreams which are not just pictures but begin also to

become indefinite feelings. Just think how often dreams can be

quite unpleasant. Many dreams are connected with anxiety. You

wake up feeling anxious. In this undefined state of

anxiety — less often it may be a state of joy — you

have the first glimmer of something which as it further

develops becomes fully present as you wake up. What is it that

glimmers forth when a dream causes, for example,

anxiety?

Such dreams are interwoven with feelings; anxiety is a feeling.

The feeling is undefined because the dream is still partly

outside the organism; yet it is far enough within to

intermingle with feeling. It interweaves with what already

lives in the soul as feeling. Only when the astral body has

entered completely do you have definite feelings. These are

conditioned by the physical organization and can now be

penetrated by mental pictures present in the astral body.

When we consider certain nightmares and anxiety dreams in the

right light we draw near to what actually takes place when the

astral body enters man's physical body. You will always find

that it is some disorder in the breathing which causes the

state of anxiety of some dreams. From this you can see clearly

that the astral body draws in and again draws out through the

breath. It is really possible to observe these things if only

the observation is thorough enough and free from prejudice.

Something can be seen here that enables us to recognize that

what weaves in dreams is in fact the astral body and that it

draws into our organism by taking hold of the breath as we wake

up.

This leads to the recognition of something else that is not

normally taken into account but is of great significance. The

human being is usually regarded as if he were simply a

physical organism, a body built up of solid matter. That

is just not true. The least part of the human body is solid,

less than ten percent. For the rest it is a water organism, an

organism of liquid, so that in reality we must think of this

organism built up in such a way that one tenth is solid (see

drawing, white lines) and the solid saturated with water (blue

lines). You only represent the human organism truly when you see

it as a column of liquid in which the solid is deposited.

| |

Diagram 2

Click image for large view | |

However, there is more to it. We must also picture the human

organism as an organism of air. The air is outside, we breathe

it in; a part of the outside air is now within us and we

breathe it out again. So we are also an air organism. Let us

draw that, too (red lines). It is just this air organism which

is taken hold of by the astral body as we wake up. We breathe

in the air, it goes through transformations the effect of which

pours through the whole organism. The oxygen takes up the

carbon and transforms it into carbonic acid. Thus, an air

process continually takes place within us.

As

we wake up the air process is permeated by the astral body. The

movement of the astral body follows the same path as the air

through the organism. The air process consists solely of

air when we sleep; when we are awake then the movements of the

astral body, as it were, swim along within what lives in us as

air processes. But now depict to yourselves the following: the

astral body draws into that which I have schematically drawn in

red and carries out its movements, in fact, carries out its

general activity, within the air organism. This all takes place

within the watery organism, which is represented in the blue

lines. When we are awake, these air processes are in reality

processes of the astral body and they continually push against

the watery organism. Man's etheric body is within the watery

organism both night and day. So you have simultaneously a

reciprocal effect between the etheric body and the astral body,

as well as between their physical counterparts which are the

air processes and the water processes. Thus, you can

visualize these processes running their course within man

between his breathing and the movements of all the bodily

fluids. Yet that is again merely a copy of what takes place

between the astral and etheric bodies.

The

whole organism consisting of solid, fluid and air is also

permeated with warmth (see drawing, yellow lines, page 38). The

whole organism has its own warmth — i.e., its own warmth

ether. On the gaseous waves moves astrality and in the warmth

flowing through the body moves the actual I or ego of

man.

So

you have the physical body as such, then the fluid body, which

is also physical but differentiated from the solid physical

body. The fluid physical body has an intimate connection

with the etheric body. Then the gaseous organism which has an

intimate connection with the astral body, and finally all the

warmth processes — that is, the warmth ether in man, which

has an intimate connection with the human I. Thus, one can say

that in the various physical constituents of man we have a

picture of the whole man. The solid part, so to speak, exists

by itself; the fluid within the organism cannot exist by

itself. Within the head we have very little solid and what

there is swims in the cerebral fluid. Within this fluid is the

etheric part of the head.

In

the breathing process the following takes place: As we breathe

in, the breath pushes inwards up through the spinal fluid

towards the brain. In our waking state the astral also moves

along this thrusting movement towards the etheric part of the

head. We have then, on the one hand, an interaction of

the movement of the cerebral fluid with the movement of

the breath, and, on the other, an interaction of the etheric

part of the head — of which what takes place in the

cerebral fluid is only an image — with the breathing

process, which is again only an image of the astrality in man.

We also have a continuous interplay of warmth; the movement of

the blood mediates the warmth. On the waves of this sea of

warmth our I also moves.

To

become clear about these interactions within man's bodily

nature it is essential that we represent them vividly to

ourselves. Only the solid organism can be observed by itself.

The fluid organism does not have the possibility of moving

in

waves the way water moves in the external world. The play of

movement in the fluid organism is an image of what takes place

in the etheric body. Again, what takes place in the delicate

processes of breathing is an image of what takes place in man's

astral body. Keeping this in mind let us once more look at the

cerebral fluid: within it certain movements take place copying

movements of the etheric body. Man acquires the etheric

body when he descends from spiritual worlds into the physical

world. Within the spiritual world he does not yet possess it.

But as man takes hold of his physical body he also takes

possession of his etheric body; he, as it were, draws out the

ether from the cosmos. He can unite with the physical body,

which he receives through heredity, only when he has drawn the

ether from the cosmos. So that all that lives in the etheric

body of man we bring with us when we take hold of the physical

body.

The

human embryo develops within the maternal body. Let us consider

the fluid within the embryo. In general physiology only the

solid components, or what appear to be solid components, are

examined, not the fluid. Were this to be investigated it would

be found that the cerebral fluid, in particular, contains an

image of all that which was present already in the ether body,

as the ether was drawn together, and which then slips into

physical man.

| |

Diagram 3

Click image for large view | |

If

this is the physical body (see drawing) in which the physical

human embryo develops — I do not draw the solid, only the

fluid embryo (red lines) — then what as astral and `I' is

present descends from the spiritual world; what has been drawn

together from the ether slips in (yellow lines). In fact, as he

dives down into his physical body the fluid part of the

organism absorbs what man brings with him. Therefore, if the

movements within the cerebral fluid of the child were to be

investigated they would be found to be like a photograph of

what the human being had been before he united with the

physical body. You see, it is very significant to realize that

a photograph is to be found in the cerebral fluid, that is to

say in the movements of the cerebral fluid, of what has taken

place before conception.

It

is fairly easy to understand that a kind of photograph of what

existed before conception is to be found in the cerebral

fluid. But let us now consider the process of breathing.

Breathing appears to be an out and out physical process because

of the way our lungs function. Air is drawn in and, under the

influence of the external world, the breathing takes place even

when we are asleep — that is, even when the eternal part of

our being is not united with the temporal part. Our breathing

is not affected by whether we are awake or asleep. When we

sleep the wave movements of the breath go through the organism;

when we are awake they, in addition, carry the astral

body. In other words, they are able to carry the astral body

but it is not incumbent on them to do so, for when we are

asleep they do not.

What follows from this? It follows that the reason the cerebral

fluid can carry on by itself is because it is isolated within

man's inner being. It constitutes a kind of continuation

of what existed before. On the other hand, nothing of what

existed before can be continued in this intimate way within our

breath. When we consider the human head, we find within the

cerebral fluid, that is, within the physical body itself, the

actual continuation of pre-natal spiritual man; whereas when we

consider the organization of the chest and the process of

breathing we find a different situation. The physical

breath takes place by itself (see drawing, yellow lines); the

spiritual is less strongly connected with the physical process

(red lines). Therefore, one must say that in the head,

spiritual man, the man of soul and spirit, is closely connected

with physical man; they have become a unity. In the chest that

is not the case — there the two are more apart; the

physical organism is more by itself and so, too, the

soul-spiritual.

| |

Diagram 4

Click image for large view | |

Let

us now compare this with the state of dreaming. When we dream

the I and astral body are outside, they are separated from the

sleeping body. However, for the chest man, that is to some

extent always the case. The chest man — that is, the man

of breath and heart, in short, rhythmic man — is the

organism for feeling. Feelings run their course like dreams

because the soul-spiritual is not so firmly connected with the

physical organism, is not so completely within physical man. So

you see, if one wants to consider the whole man one must take

into account these different interactions of what pertains to

the soul and what pertains to the body.

In

our materialistic age the human being is considered only in the

most external way. This is evident from the way modern science

looks upon man as if he were nothing but a solid organism

within which the soul is somehow active. On this basis it is

impossible to visualize how, for example, an impulse of will,

experienced purely within the soul, can lead to the lifting of

the arms or legs. In fact, from the point of view of what we

experience as the soul's part in an act of will, the human

organism, as conceived by modern anatomy and physiology, is

like a piece of wood, as alien to the soul as a piece of wood.

What in physiology today is described as human legs is like a

description of two pieces of wood. They are related to the soul

as if they were wooden legs. As little as the soul could have

any relationship with two pieces of wood lying about, just as

little could it have any relationship with legs as described by

modern physiology. However, human legs are penetrated by

liquid. Here we already come upon something in which it is

easier to understand that the spiritual can be active within

it. Yet, it is still difficult.

Once we come to the gaseous, the airy element, then we are in a

physical material so fine that it is much easier to visualize

the soul element to be within it, and easier still when we come

to warmth. Just think how close a connection can come

about between the warmth of the physical organism and the soul.

You may at some time have had a terrible fright and grown quite

hot. There you have an inner experience of the connection

between the soul and the warmth in the physical organism. In

fact, when we examine the solid, fluid, gaseous and warmth

components of the whole organism, we gradually arrive at the

soul.

It

can be said that the 'I' takes hold of the inner warmth; the

astral body of the gaseous; the ether body of the fluid and

only the solid remains untouched; in the solid nothing enters.

Picture to yourselves the way the human organism functions: You

have the human brain (see drawing, page 46) that has fluid in

it and also solid parts into which, as I said, the soul does

not enter. The solid parts are, in reality, salt deposits;

whatever solid we have within us is always salt-like deposit.

Our bones consist solely of such deposits. In the brain very

fine deposits continually occur and again dissolve. There

is always a tendency in our brain to bone formation. The

brain has a tendency to become quite bony. But it does not

become bony because everything is in movement and is

continually dissolved. When we examine the organism, especially

the brain, we first find within it a condition of warmth,

and within the warmth the air which is the bearer of the astral

body and is continually playing into the cerebral fluid while

being breathed in and out. We then have the cerebral fluid in

which the ether body lives. Then we come to the solid into

which the soul cannot enter because it consists of

deposited salt. Because of this salt formation, which is

less than ten percent of the total organism, we have within us

something into which the soul cannot enter.

As

human beings we have an organism; within this organism

there are warmth, gaseous and fluid elements, all of which the

soul can penetrate. But there is something which the soul

cannot penetrate. This is comparable to having objects on

which light falls but cannot penetrate and is therefore

thrown back. Let us say we have a mirror; light cannot go

through it and is therefore reflected. Similarly, the soul

cannot penetrate the solid salt organism and is, therefore,

continually reflected.

If

this were not the case, there would be no consciousness at all.

Your consciousness consists of soul experiences reflected from

the salt organism. You are not aware of the soul life as it is

absorbed by the warmth, gaseous and fluid organism; you

experience it only because the soul life within the

warmth, gaseous and fluid, is reflected everywhere by salt,

just as sunbeams are reflected by a mirror. The outcome

of this reflection is our mental pictures.

| |

Diagram 5

Click image for large view | |

When someone deposits too much salt — salt always takes on

forms — then he produces a lot of mental pictures; he

becomes rich in thoughts. If too little salt is secreted the

thoughts have vague outlines, like reflections from a faulty

mirror. Or, said differently, when too much salt is secreted

thoughts predominate and become very precise, and he who has

them becomes pedantic. He is convinced of the rightness

of his thoughts because they arise from so much solid, he

becomes materialistic. When too little salt is secreted, or

perhaps too much in the rest of the organism but too little in

the head, then the thoughts become indefinite and the

person becomes fanciful or perhaps he becomes a mystic.

Our soul life is dependent on the material processes taking

place within us.

It

may be necessary, when someone is too prone to fanciful

ideas, to administer some remedy that will enable him to

deposit more salt or else give better form to the salt he does

deposit. He will then escape from his fantasies. However, one

should not make too great an effort to cure a human being

by physical means of his fantasies or pedantry; not much can be

done anyway. To do something different is more important

and can be of great value — someone who knows how to

observe human beings in regard to both soul and body will

notice if there is too much sediment, whether in the head, or

in the organs of the rhythmic or metabolic systems. He will

notice it because the whole thought configuration becomes

different. The manner in which a person alters his thoughts can

contribute significantly to a diagnosis. But such delicate

reactions are not often noticed. For example, someone may

suddenly make mistakes repeatedly when speaking. He does not

normally do so, but suddenly he makes mistakes again and again.

It may last a few days and then cease. He has suffered a slight

ailment, and the mistakes in speaking are merely a

symptom. Such instances can often be described quite

exactly.

For

example, someone may for a few days secrete too much gastric

acid. Now what occurs? This gastric acid dissolves

certain substances in the stomach, which ought to pass on

beyond the stomach. This means that the organism is deprived of

these substances with the result that the person's inner

mirror pictures lack the necessary sharpness. His thoughts

become vague and he makes mistakes in speaking. You will have

realized what must be done: One must provide a remedy that will

ensure less acidity in the stomach, then the person's thoughts

will again become ordered. His digestion is now in order and he

ceases to make mistakes when speaking.

Or

take the example of someone who absorbs gastric acid too

intensely. This can occur if the spleen is abnormally

active. When this happens the gastric acid is distributed

throughout the body; the body, as it were, becomes all stomach.

Such acid sediments are, in fact, the cause of many illnesses.

A specific pricking pain may be felt or, if the head is

affected, a feeling of dullness. When you look at such a person

with insight it will often be found that the absorption of all

the acidity has created in him a certain greediness. When

someone is permeated with acidity his eyes may lose their

friendly expression. If someone is suffering from too

much acidity his eyes will reveal it. It is sometimes possible

to restore his friendly expression by administering an

acid that can be digested in the stomach because it is of a

kind that has no tendency to spread throughout the

organism.

The

reason I am saying all this is to show you that the science of

the spirit meant here does not simply contemplate the human

soul in a nebulous way. It recognizes the soul as the ruler and

builder of the body, active within it everywhere.

The

human organism is described nowadays as if it were solid

through and through; the solid alone is taken into

account. It is impossible to arrive at any conception of

how the soul actually exists within the body unless one also

considers the fluid, gaseous and warmth elements of the

organism. The soul does not live in the solid part of the

organism; it does not enter the solid any more than light

penetrates a mirror. Light is thrown back from the

mirror, the soul retreats everywhere from the salt.

The

peculiarity of the soul is that it is deflected from the bones

(see drawing, red lines). We carry our bones within us empty of

soul. The soul is not within them but is rayed back into the

organism.

| |

Diagram 6

Click image for large view | |

The

bones in the skull are really ingeniously arranged. The soul

rays out in all directions and is reflected into our inner

being. We do exist within the skull bones but only as solid

physical man. If we would make a comprehensive sketch of the

head we would have to depict the soul as raying out

within the head (see drawing, red lines). If nothing else

happened, we would be in a dull unconscious condition. However,

as the soul cannot enter the bones of the skull it is rayed

back into our inner being (arrows, short red lines).

| |

Diagram 7

Click image for large view | |

We

experience the soul only when it is reflected into our

inner being. So, you see how matters stand: The reality

is that you have the soul within you rayed back from the mirror

of the skull bones.

Spiritual science does not exclude what is material; on the

contrary, recognition of how the soul controls matter makes it,

at last, comprehensible. After all one does not come to know

that someone is a baker by the fact that he makes certain

movements, but from knowing that the movements he makes

shape the rolls and croissants. Neither does one come to know

the soul through abstract considerations but by knowing that a

reflection of the soul's activity is to be found in the

physical organism. It is a question of understanding the

organism rightly and recognizing that it is an image of the

soul. If we cannot make the effort to understand even

man's physical nature we shall never learn to know the soul. We

must have the goodwill to understand how human nature comes to

expression through the physical. What is usually spoken

of as soul, by those who will not approach the physical with

spiritual insight, is something utterly unreal. It is as unreal

as if you had a tasty meal before you and, instead of eating

it, tried to eat its reflection in a mirror standing beside it.

One can become knowledgeable about the soul only by

observing her creative activity and not by persisting to regard

it as a mere abstraction. And one should certainly not adopt

the view that to be a conscientious spiritual scientist

one must scorn the material. Rather should the material be

understood spiritually; it will then reveal itself as spirit

through and through. To do otherwise is to live in

intellectual abstractions, and they obscure rather than

enlighten.

|